A General Approach for Parisian Stopping Times under Markov Processes

Abstract

We propose a method based on continuous time Markov chain approximation to compute the distribution of Parisian stopping times and price Parisian options under general one-dimensional Markov processes. We prove the convergence of the method under a general setting and obtain sharp estimate of the convergence rate for diffusion models. Our theoretical analysis reveals how to design the grid of the CTMC to achieve faster convergence. Numerical experiments are conducted to demonstrate the accuracy and efficiency of our method for both diffusion and jump models. To show the versality of our approach, we develop extensions for multi-sided Parisian stopping times, the joint distribution of Parisian stopping times and first passage times, Parisian bonds and for more sophisticated models like regime-switching and stochastic volatility models.

Keywords: Parisian stopping time, Parisian options, Parisian ruin probability, Markov chain approximation, grid design.

MSC (2020) Classification: 60J28, 60J60, 91G20, 91G30, 91G60.

JEL Classification: G13.

1 Introduction

Consider a stochastic process and define

| (1.1) |

for a given level . The ages of excursion of below and above are given by and , respectively. Consider the following two stopping times:

| (1.2) |

which are called Parisian stopping times. () is the first time that the age of excursion of above (below) reaches . In these definitions, we use the convention that and .

Parisian stopping times appear in important finance and insurance applications. Parisian options are proposed in Chesney et al. (1997) as an alternative to barrier options and they have the advantage of being less prone to market manipulation (Labart (2010)). These options are activated or cancelled if the process stays long enough below or above a prespecified level. In the insurance literature, the Parisian stopping time for the excursion below the solvency level is used to define the ruin event (e.g., Dassios and Wu (2008), Czarna and Palmowski (2011), Loeffen et al. (2013)).

There is an extensive literature on the study of Parisian stopping times and their applications in finance and insurance with many papers focused on specific models. For the Brownian motion and the geometric Brownian motion model, see Chesney et al. (1997), Bernard et al. (2005), Dassios and Wu (2010), Dassios and Wu (2011), Zhu and Chen (2013), Dassios and Lim (2013), Dassios and Zhang (2016), Le et al. (2016), Dassios and Lim (2017) and Dassios and Lim (2018). For models with jumps, methods for Parisian option pricing were developed in Albrecher et al. (2012) for Kou’s double-exponential jump-diffusion model and in Chesney and Vasiljević (2018) for the hyper-exponential jump-diffusion model. Czarna and Palmowski (2011) and Loeffen et al. (2013) derived the ruin probability for spectrally negative Lévy processes. In addition, Chesney and Gauthier (2006), Le et al. (2016) and Lu et al. (2018) studied American-style Parisian option pricing under the Black-Scholes model while Chesney and Vasiljević (2018) dealt with the hyper-exponential jump-diffusion model. As for the hedging of Parisian options, Kim and Lim (2016) developed a quasi-static strategy and tested it under the double-exponential jump-diffusion model.

Several numerical methods have also been applied to the Parisian option pricing problem. Baldi et al. (2000) developed a Monte Carlo simulation method based on large deviation estimates for general diffusions. For the Black-Scholes model, Avellaneda and Wu (1999) proposed a trinomial tree approach while Haber et al. (1999) developed an explicit finite difference scheme to numerically solve the pricing PDE, which is not unconditionally stable. These two methods can also be applied to general diffusions, but they need to incorporate the current length of excursion as an additional dimension. Furthermore, they may require a very small time step to achieve a target accuracy level, making them inefficient. If the model contains jumps, the lattice method and the finite difference approach will face more challenges for accuracy and efficiency.

In this paper, we aim to develop a computationally efficient approach for Parisian stopping time problems that is applicable to general Markov models. We consider a one-dimensional (1D) Markov process living on an interval with its infinitesimal generator given by

| (1.3) |

for (the space of twice continuously differentiable functions on with compact support) with . The quantities , , are known as the drift, volatility and jump measure of , respectively. We would like to obtain the distribution of and , i.e., . The Laplace transform of the probability as a function of is given by

| (1.4) |

For a general Markov process, there is no analytical solution for this transform. Our idea is approximating by a continuous time Markov chain (CTMC). We will show later that the Laplace transform of under a CTMC model is the solution to a linear system which involves the distribution and the Laplace transform of a first passage time of the CTMC, and this solution can be obtained in closed form. To recover the distribution of , we simply invert its Laplace transform numerically using the efficient algorithm of Abate and Whitt (1992). Using the result for , we can compute the Laplace transfrom of a Parisian option price as a function of maturity in closed form for a CTMC model. We can further solve a range of Parisian problems under a CTMC model such as the distribution of the multi-sided Parisian stopping time, the joint distribution of a Parisian stopping time and a first passage time and the pricing of Parisian bonds. For more complex models like regime-switching models and stochastic volatility models, we can also approximate them by a CTMC and solve the Parisian stopping time problems. Thus, our approach is very general and versatile. Numerical experiments for various popular models further demonstrate the computational efficiency of our method, which can outpeform traditional numerical methods significantly.

Our paper fits into a burgeoning literature on CTMC approximation for option pricing. Mijatović and Pistorius (2013) used it for pricing European and barrier options under general 1D Markov models. They showed that the barrier option price can be obtained in closed form using matrix exponentials under a CTMC model. Sharp converegnce rate analysis of their algorithm for realistic option payoffs is a challenging problem. Answers are provided for diffusion models first in Li and Zhang (2018) for uniform grids and then in Zhang and Li (2021a)) for general non-uniform grids while the problem still remains open for general Markov models with jumps. For diffusions, Zhang and Li (2021a) also developed principles for designing grids to achieve second order convergence whereas the algorithm only converges at first order in general. The idea of CTMC approximation has also been exploited to develop efficient methods for pricing various types of options for 1D Markov models: Eriksson and Pistorius (2015) for American options, Cai et al. (2015), Song et al. (2018), Cui et al. (2018) for Asian options, and Zhang and Li (2021b) and Zhang et al. (2021) for maximum drawdown options. Furthermore, CTMC approximation can be extended to deal with more complex models where the asset price follows a regime-switching process (Cai et al. (2019)) or exhibits stochastic volatility (Cui et al. (2017, 2018, 2019)).

One can view the present paper as a generalization of Mijatović and Pistorius (2013) and Zhang and Li (2019) from barrier options to Parisian options. However, this generalization is by no means trivial. First, the Parisian problem is much more complex than the first passage problem as it involves the excursion of the process. Second, there is considerable challenge in sharp convergence rate analysis. Even for barrier options, the sharp convergence rate of CTMC approximation is only known for diffusion models, and the difficulty mainly stems from the lack of smoothness in the option payoffs. In this paper, we focus on analyzing the convergence rate of our algorithm for Parisian problems under diffusion models. We use the spectral analysis framework in Zhang and Li (2021a), but there is an important difference which makes the analysis for Parisian problems much harder. Here, we must carefully analyze the dependence of solutions to Sturm-Liouville and elliptic boundary value problems on variable boundary levels whereas in the barrier option problem the boundaries are fixed. Furthermore, we need to establish some new identities that enable us to obtain the sharp rate. Our analysis not only yields the sharp estimate of the convergence rate, but also unveils how the grid of the CTMC should be designed to achieve fast convergence.

For the sake of simplicity, our discussions in the main text will be focused on the algorithms for single-barrier Parisian stopping times and the down-and-in Parisian option as well as their convergence analysis. Extensions for other cases are provided in the appendix. The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we derive the Laplace transforms of Parisian stopping times and Parisian option prices under a general CTMC model with finite number of states. Section 3 reviews how to construct a CTMC to approximate a general jump-diffusion and establishes the convergence of this approximation for the Parisian problems. Section 4 analyzes the convergence rate for diffusion models and proposes grid design principles to ensure second order convergence. Section 5 shows numerical results for various models and Section 6 concludes the paper. In Appendix A, we extend our method to deal with multi-sided Parisian stopping times, the joint distribution of Parisian stopping times and first passage times, Parisian bonds and the Parisian problem for regime-switching and stochastic volatility models. Proofs for the convergence rate analysis are collected in Appendix B.

2 Parisian Stopping Times Under a CTMC

Consider a CTMC denoted by which lives in the state space . The transition rate matrix of is denoted by with indicating the transition rate from state to , and . The action of on a function is defined as

| (2.1) |

For any , we also introduce the notations

| (2.2) | |||

| (2.3) |

which are the CTMC states that are the right and left neighbor of , respectively. We also define . Note that is different from in that if , but we always have . We slightly abuse the notation here to avoid introducing a new one.

In this section, we first derive the Laplace transform of Parisian stopping times and then the Laplace transform of the price of a down-and-in Parisian option.

2.1 Laplace Transform of Parisian Stopping Times

Define

| (2.4) |

which is the Laplace transform of given with an indicator for the process landing on at . The joint distribution of and is characterized by . We also define

| (2.5) |

which is the Laplace transform of given . To calculate and , we introduce the following quantities that involve the first passage times of :

| (2.6) | |||

| (2.7) | |||

| (2.8) | |||

| (2.9) | |||

| (2.10) |

Remark 2.1.

Throughout the paper, the variable before the semicolon indicates the initial state and the variable after it indicates the state at a stopping time or fixed time.

Using the strong Markov property of , we can derive the following two equations for and using the first passage quantities.

Theorem 2.1.

For ,

| (2.11) | ||||

| (2.12) | ||||

| (2.13) | ||||

| (2.14) |

Proof.

First, consider the case . We have

| (2.15) |

The first term represents the case that does not cross from below by time . In this case, and hence , where is the probability that the first time greater than or equal to exceeds and .

The second term stands for the case that crosses from below before time . Using the strong Markov property, the process restarts at from and the clock is reset to zero. Thus, the second term becomes

| (2.16) | |||

| (2.17) |

Next, consider the case . The clock would not tick until crosses from above, at which time the process restarts at by the strong Markov property and starts ticking. Thus, we have

| (2.18) | ||||

| (2.19) |

Putting these results together yields the equation for . The equation for is obtained by summing the equation for over . ∎

Solving (2.12) and (2.14) requires the quantities for first passage times, which we show are solutions to some equations.

Proposition 2.1.

We have the following equations for , and .

-

1.

satisfies

(2.20) -

2.

satisfies

(2.21) Here can be written as with and as solutions to the following equations:

(2.22) (2.23) -

3.

satisfies

(2.24)

Proof.

We derive the equation for and the others can be obtained in a similar manner. Let and . As is a piecewise constant process, we have as . Using the monotone convergence theorem, we have

| (2.25) |

Denote the transition probability of by . We have that for and . Then for ,

| (2.26) | ||||

| (2.27) |

Therefore,

| (2.28) |

Taking to shows the ODE. The boundary and initial conditions ara obvious. ∎

We introduce some matrices and vectors: is the -by- identity matrix. Let , , where diag means creating a diagonal matrix with the given vector as the diagonal. is the -dimensional vector of ones, and .

It is not difficult to see that the equations in Proposition 2.1 can be solved analytically and the solutions are expressed using matrix operations as follows: for ,

| (2.29) | |||

| (2.30) | |||

| (2.31) | |||

| (2.32) |

Let

| (2.33) | |||

| (2.34) |

Then, the equation in Theorem 2.1 becomes

| (2.35) |

The solution is

| (2.36) |

Subsequently, can be calculated as

| (2.37) |

where is a -dimensional vector of ones.

Remark 2.2 (Time complexity for a general CTMC).

Calculating , , and involves matrix exponentiation or inversion whose time complexity is generally . In addition, calculating also involves matrix inversion so its cost is also . Aggregating the costs over all steps yields an overall time complexity of to calculate and .

Remark 2.3 (Time complexity for birth-and-death processes).

Significant savings in computations are possible when is a birth-and-death process. In this case, it is easy to see that only when and only when . Consequently, (2.12) reduces to

| (2.38) | ||||

| (2.39) |

Setting respectively in (2.39), we obtain

| (2.40) | |||

| (2.41) |

Solving this linear system for and yields

| (2.42) | |||

| (2.43) |

For a general , can be found by substituting these two equations back to (2.39).

Recall that . We have

| (2.44) | |||

| (2.45) | |||

| (2.46) | |||

| (2.47) |

Then, , and . Using (2.42) and (2.43), we get

| (2.48) | |||

| (2.49) |

The, by (2.39) we obtain

| (2.50) |

Subsequently, we get

| (2.51) |

Note that is a tridiagonal matrix and so is . Hence calculating and only costs as opposed to in the general case. Moreover, for any , can be calculated as,

| (2.52) |

where the RHS can be found by solving a sequence of linear systems with the LHS given by and the total cost is . Hence the cost of computing and is . Calculating and involves , and which can be done with complexity of either or . Therefore, it costs to calculate . For , we need to compute the matrix and it costs using the approximation in (2.52). In our implementation, we use the extrapolation technique in Feng and Linetsky (2008), which achieves good accuracy with a small ( is much smaller than ).

2.2 Laplace Transform of The Option Price

We derive the Laplace transform of the price of a Parisian down-and-in option w.r.t. maturity under the CTMC . The option price is given by

| (2.53) |

Theorem 2.2.

The Laplace transform of w.r.t. has the following representation:

| (2.54) |

where is the Laplace transform of the price of a European option with payoff w.r.t. maturity and it satisfies the linear system

| (2.55) |

Proof.

By the strong Markov property of , we get

| (2.56) | ||||

| (2.57) | ||||

| (2.58) | ||||

| (2.59) | ||||

| (2.60) | ||||

| (2.61) |

We can deduce for from its definition, so the summation above is done only over those .

Using the expression in Theorem 3.1 of Mijatović and Pistorius (2013) for the European option price, we can calculate the Laplace transform of the option price as

| (2.62) |

where . Thus, solves the linear system as stated. ∎

Let . Theorem 2.2 shows that

| (2.63) |

In general, the cost of computing and is . So the time complexity for computing is . Significant savings are possible for birth-and-death processes. The cost of computing is only because is diagonal. For , it is given by

| (2.64) |

Computing , and involves calculating the exponential of a tridiagonal matrix times a vector, which can be done at cost using the approximation (2.52) with time steps. Thus, the total cost for a birth-and-death process is only .

Remark 2.4 (Parisian ruin probability).

In an insurance risk context, is known as the Parisian ruin time (see e.g., Czarna and Palmowski (2011), Loeffen et al. (2013) and Dassios and Wu (2008)) for some pre-specified and . One can calculate with a finite and for the ruin probability in a finite horizon and in an infinite horizon, respectively.

To apply our method, set and thus . In this case, , and hence . The finite horizon ruin probability can then be obtained by evaluating the Laplace inversion of at as described in the next subsection. For the infinite horizon ruin probability, we apply the Final Value Theorem of Laplace transform, which implies

| (2.65) |

The limit can be well approximated by for a sufficiently small .

2.3 Numerical Laplace Inversion

We utilize the numerical Laplace inversion method in Abate and Whitt (1992) with Euler summation to recover the distribution function of a Parisian stopping time and the price of a Parisian option. Suppose a function has known Laplace transform . Then can be recovered from as

| (2.66) |

In our numerical examples, we set and and this choice already provides very accurate results. We summarize our algorithm for a CTMC combined with numerical Laplace inversion in Algorithm 1. Modifications can be made following Remark 2.3 to simplify the computation for birth-and-death processes.

Remark 2.5.

Suppose terms are used in (2.66) for the Laplace inversion. Then the overall complexity of calculating the distribution of a Parisian stopping time or the price of a Parisian option is for a general CTMC and for a birth-and-death process.

3 Markov Chain Approximation and Its Convergence

In order to make the paper self-contained, we briefly review the construction of CTMC approximation below and refer readers to Mijatović and Pistorius (2013) for more detailed discussions. We then prove its convergence in our problem.

3.1 Construction of CTMC Approximation

We construct a CTMC on the space with to approximate the Markov process with its generator given by (1.3). Let , which is the set of interior states. For each , define , , and set , and for any and . For any and , let

| (3.1) | |||

| (3.2) |

Then can be approximate as,

| (3.3) |

where , . For each , let

| (3.4) |

We further approximate and using central difference. The resulting transition rate matrix for is as follows. For each ,

| (3.5) | |||

| (3.6) | |||

| (3.7) | |||

| (3.8) |

We set and as absorbing states for and hence for all .

3.2 Convergence

We study the convergence of CTMC approximation for a general Markov process. Let be the original process and is a sequence of CTMCs that converges to weakly on , the Skorokhod space of càdlàg real-valued functions endowed with the Skorokhod topology. Sufficient conditions for the weak convergence can be found in e.g., Mijatović and Pistorius (2013), which we do not repeat here for the sake of brevity. In the following, we prove convergence for the distribution of Parisian stopping times and Parisian option prices.

The key of the proof is to establish the continuity of on a subset of which has probability one. To characterize such sets, we introduce the following definitions.

| (3.9) |

In this way, tracks the length of each excursion. We also consider the following subsets of .

| (3.10) | |||

| (3.11) | |||

| (3.12) | |||

| (3.13) |

Theorem 3.1.

Suppose is càdlàg (right continuous with left limits), , and . Then, for any bounded function whose discontinuity points are and such that and ,

| (3.14) |

Proof.

implies that if is bounded and continuous on some subset of such that , then it holds that

| (3.15) |

With the assumption that , and , it suffices to establish the continuity of on . For , suppose as on . Note that for , we have for .

-

•

If . Then there exists such that . Let . Since is dense, we can find a that is small enough such that , is continuous at and , and . By Proposition 2.4 in Jacod and Shiryaev (2013) which shows the continuity of the supremum process, . Since , we conclude that for sufficiently large . Therefore, we have .

-

•

If . Since , there is such that and . As , . Since is dense, we can find a that is small enough such that , is continuous at and for any , and for any . In the same spirit of Proposition 2.4 in Jacod and Shiryaev (2013), we can show that the continuity of the infimum process. Hence we have for sufficiently large , for any . It follows that the age of excursion below of up to time cannot exceed . This implies for sufficiently large . Therefore, .

Combing the arguments above, we obtain the continuity of on . This concludes the proof. ∎

4 Convergence Rate Analysis for Diffusion Models

We assume the target diffusion process lives on a finite interval with absorbing boundaries. For diffusions that are unbounded, it means that we consider their localized version. The absolute value of the localization levels can be chosen sufficiently large so that localization error is negligible compared with error caused by CTMC approximation. The latter is the focus of our analysis and the former is ignored.

We consider a sequence of CTMCs with grid size () and fixed lower and upper levels, i.e., , . Let . We impose the following condition on .

Assumption 1.

There is a constant independent such that for every ,

| (4.1) |

This assumption requires the minimum step size cannot converge to zero too fast compared with the maximum step size, which is naturally satisfied by grids used for applications.

Let denote the generator matrix of . We specify and as absorbing boundaries for the CTMC to match the behavior of the diffusion. Throughout this section, we impose the following conditions on the drift and diffusion coefficient of and the payoff function of the option.

Assumption 2.

Suppose . The payoff function is Lipschitz continuous on except for a finite number of points in .

The coefficients of many diffusion models used in financial applications are sufficiently smooth, so they satisfy Assumption 2. It is possible to extend our analysis to handle diffusions with nonsmooth coefficients using the results in Zhang and Li (2021a), but for simplicity we only consider the smooth coefficient case in this paper.

For some diffusions, vanishes at . To fit them into our framework, we can localize the diffusion at . By choosing a very small , the approximation error is negligible.

We introduce the notation for quantities bounded by for some constant which is independent of and .

4.1 Outline of the Proofs

Recall that the Laplace transform of the option price is given by

| (4.2) |

where satisfies the linear system

| (4.3) |

and is given by

| (4.4) | ||||

| (4.5) |

where

| (4.6) | |||

| (4.7) |

In the following, we will analyze the convergence of these quantities to their limits, which are the corresponding quantities for the diffusion model as ensured by Theorem 3.1, which proves convergecence of CTMC approximation.

-

1.

Analysis of (see (4.37) and (4.39)): The quantity is essentially the up-and-out barrier option price with as the effective upper barrier and payoff function . By Zhang and Li (2019), is represented by a discrete eigenfunction expansion based on the eigenvalues and eigenvectors from a matrix eigenvalue problem. Its continuous counterpart also admits an eigenfunction expansion representation where the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions are solutions to a Sturm-Liouville eigenvalue problem on the interval . To analyze the approximation error, we can first analyze the errors for the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions and then exploit the eigenfunction expansions. However, there is one catch. In general, is not equal to unless is put on the grid. Therefore, the eigenpairs are dependent on the grid and we must carefully analyze the sensitivities of eigenpairs with respect to the boundary (see the second part of Lemma 4.1). Hence we have additional error terms like in (4.37) and (4.39) caused by not on the grid.

-

2.

Analysis of (see (4.54) and (4.56)): It can be split into two parts and as in (4.44). satisfies a linear system which is essentially a finite difference approximation to a two-point boundary value problem with effective boundaries and . The error caused by applying finite difference approximation can be analyzed by standard approaches. However, we need to derive the dependence of the solution to the two-point boundary value problem on the right boundary as is not necessarily on the grid. can be analyzed similarly as once we obtain the error of .

-

3.

Analysis of (see (4.61) and (4.63)): satisfies a linear system which results from finite difference approximation to a two-point boundary value problem with boundaries and . Like , the error caused by finite difference approximation can be analyzed by standard approaches. In this case, is dependent on the grid and hence we need to derive the sensitivity of the solution to the two-point boundary value problem w.r.t. the left boundary. In particular, we show that the first and second order derivatives w.r.t. the left boundary form a nonlinear differential equation (4.60).

-

4.

Analysis of (see (4.68)): By setting in , and in and expanding them around , we have the error estimates for , and as shown in (4.39), (4.56) and (4.63). Substituting these estimates to (4.6) and (4.7) yields the error estimates of and . Afterwards, the error of can be obtained by applying all the error estimates obtained so far to (4.4). We would like to emphasize that the boundary dependent estimates of eigenvalues, eigenfunctions and solutions to the two-point boundary value problems are the key to cancel many lower order error terms. The final error is given by , which indicates that second order convergence of can be ensured if is put on the grid.

-

5.

Analysis of the option price (see (4.78)): satisfies a linear system which is a finite different approximation to a two-point boundary value problem with a nonsmooth source term. We show that the error of is (see (4.70)), where in general and if all the discontinuities are placed exactly midway between two neighboring grid points. Using this estimate and the one for in (4.2) and then applying the error estimate of the trapezoid integration rule yield the error estimate of the option price.

4.2 Analysis of

By Zhang and Li (2019), admits an eigenfunction expansion for :

| (4.8) |

where is the number of points in ,

| (4.9) | |||

| (4.10) |

and , are the pairs of solutions to the eigenvalue problem,

| (4.11) |

These eigenfunctions are normalized and orthogonal under the measure . That is,

| (4.12) |

where is the Kronecker delta.

As shown in Zhang and Li (2019), admits a self-adjoint representation

| (4.13) |

with for , for , and

| (4.14) |

For , satisfies

| (4.15) |

It can be written as the difference of two parts: with satisfying

| (4.16) |

and satisfying

| (4.17) |

admits the eigenfunction expansion,

| (4.18) |

To study the convergence of , we consider the boundary-dependent eigenvalue problem

| (4.19) |

where , and is a second-order differential operator given by

| (4.20) |

The sequence of solutions are , . Consider the speed density of the diffusion given by

| (4.21) |

The eigenfunctions are normalized and orthogonal under the speed measure . That is,

| (4.22) |

We also consider the solution to the equation

| (4.23) |

and

| (4.24) |

Lemma 4.1.

Under Assumption 1 and Assumption 2, the following results hold.

-

1.

For the speed density, there holds that for ,

(4.25) There exist constants independent of and such that

(4.26) -

2.

with , with , , are well-defined and continuous for and in any closed interval . We also have

(4.27) (4.28) (4.29) (4.30) Moreover, there exist constants independent of , and such that

(4.31) (4.32) -

3.

For and , we have

(4.33) (4.34) (4.35) (4.36)

4.3 Analysis of

Recall that

| (4.44) |

with satisfying

| (4.45) |

In addition, admits an eigenfunction expansion given by

| (4.46) | |||

| (4.47) |

To study the convergence of , we consider the solution to the following boundary-dependent PDE,

| (4.48) |

can be written as , where is the solution to

| (4.49) |

and is the solution to

| (4.50) |

We can represent using an eigenfunction expansion as follows:

| (4.51) |

Lemma 4.2.

4.4 Analysis of

satisfies the equation

| (4.58) |

We consider the following boundary-dependent differential equation with solution :

| (4.59) |

4.5 Convergence Rates of and Option Prices

Theorem 4.1.

To obtain the convergence rate of option prices, we first analyze . Recall that is the set of discontinuities of the payoff function .

Proposition 4.3.

Let

| (4.71) |

The error of for approximating can be decomposed into four parts as follows:

| (4.72) | |||

| (4.73) | |||

| (4.74) | |||

| (4.75) | |||

| (4.76) | |||

| (4.77) |

The first to the third parts of errors can be analyzed using the estimates for the approximation errors for and . The last part is the error of a numerical integration scheme which can be analyzed with the estimate of in Lemma 4.1. Utilizing the previous estimates, we obtain the following theorem.

Theorem 4.2.

Remark 4.1.

Setting , we obtain the error estiamte for as .

4.6 Grid Design

From Theorem 4.2, we need to place on the grid (in this case ) and strikes in the midway to ensure second order convergence. This can be achieved by the piecewise uniform (PU) grid construction proposed in Zhang and Li (2021a). For example, suppose the payoff has a single strike at , then the PU grid can be constructed as follows.

| (4.79) | ||||

| (4.80) |

where , and . The case of is similar.

Although this grid design is inspired by the convergence rate results for diffusion models, we can also apply it to pure-jump and jump-diffusion models to remove convergence oscillations and make extrapolation applicable to accelerate convergence, as shown by numerical examples.

Remark 4.2.

If , we do not have a grid that can meet both requirements that should be on the grid and should be placed midway. However, we can still achieve second order convergence in the following way. We first construct a grid that places midway to calculate on this grid. Then we use a second grid with on it to calculate . Since these two grids do not coincide, we need the values of at points off the first grid and they can be obtained by interpolating the values of on the first grid using a high-order interpolation scheme.

5 Numerical Examples

To illustrate the performance of our algorithm, we compute the distribution of Parisian stopping times and price Parisian options under several popular models. Throughout this section, we use the following parameter setting: the risk-free rate , the dividend yield , the option’s maturity , the reference level for the length of excursion , the initial stock price , the barrier level , and the strike price , except for the standard Brownian motion model. We consider the following representative models:

-

•

The standard Brownian (BM).

-

•

The Black-Scholes (BS) model: .

-

•

Regime-switching BS model with regimes: volatility is in the first regime and in the second. The rate of transition is 0.75 from regime 1 to 2 and 0.25 from 2 to 1.

-

•

Kou’s model (Kou and Wang (2004)): . This is a popular jump-diffusion model with finite jump activity.

-

•

Variance Gamma (VG) model (Madan et al. (1998)): , , . This is a commonly used pure jump model with infinite jump activity.

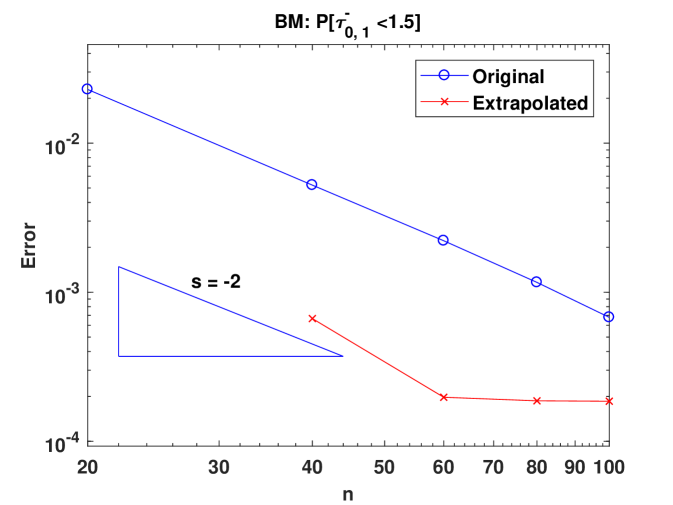

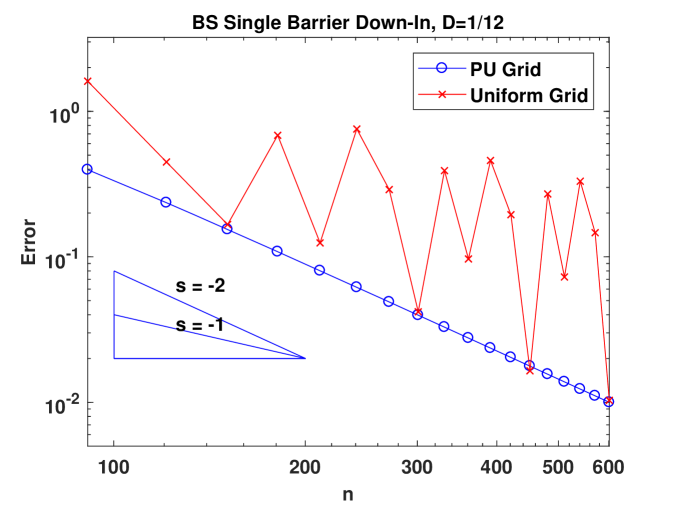

Figure 1 shows the convergence of under the standard BM model by plotting errors against the number of CTMC states. Apparently we can observe second order convergence in both plots (see the blue lines) for and , which verifies the theoretical convergence rate. Furthermore, the plots demonstrate that Richardson’s extrapolation can substantially reduce the error as seen from the red lines.

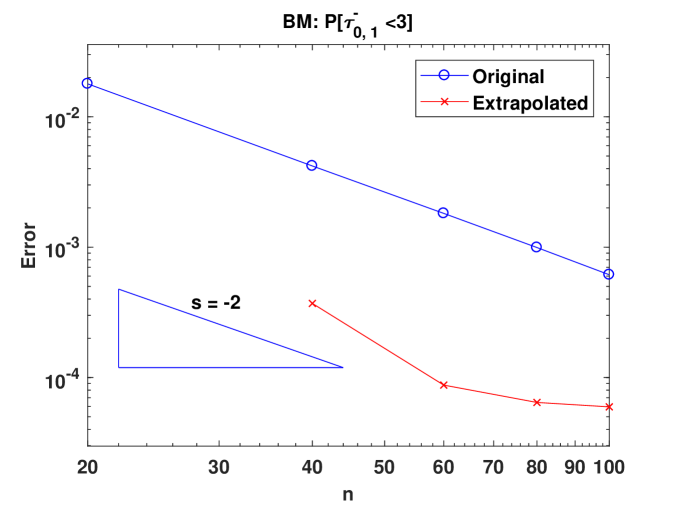

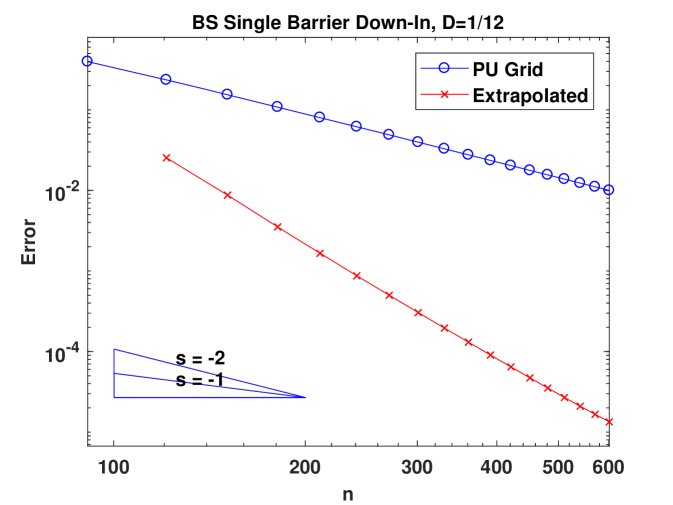

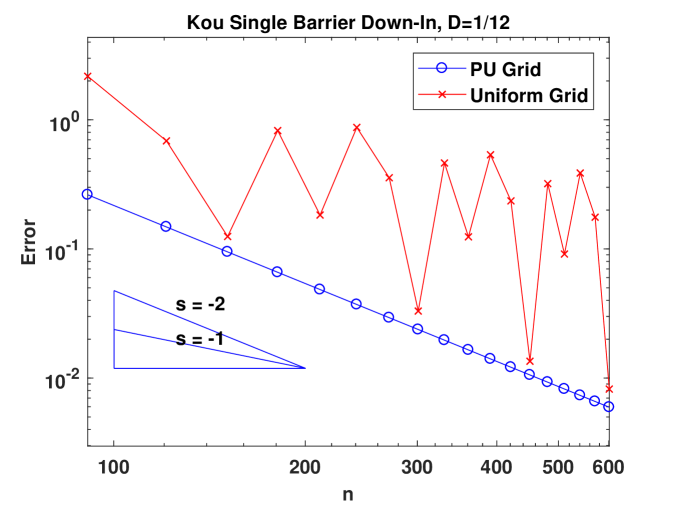

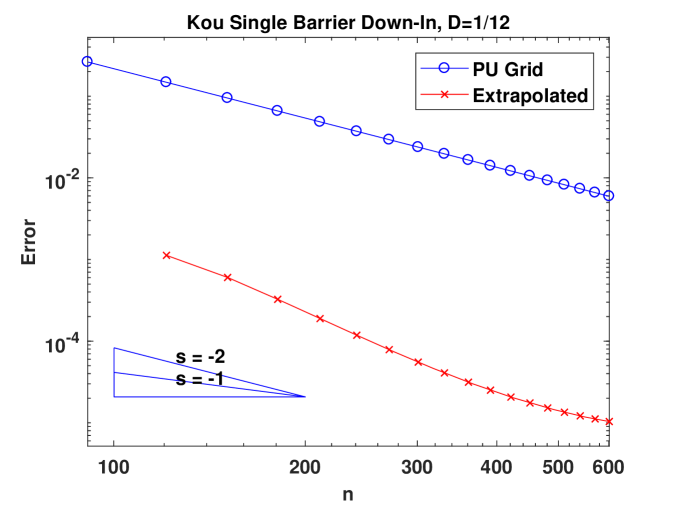

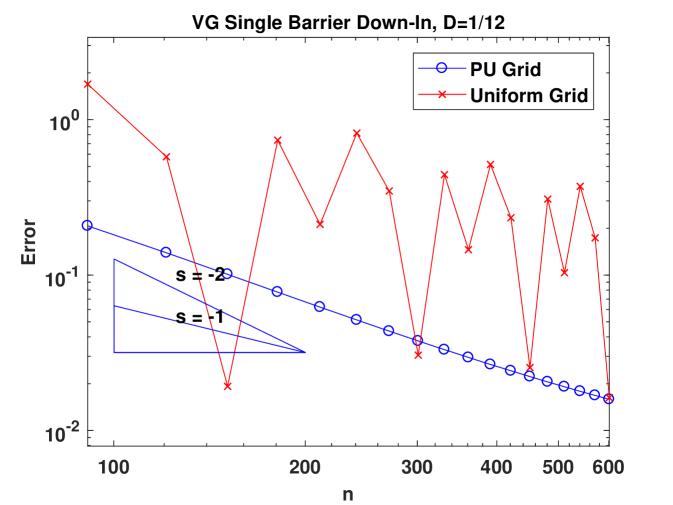

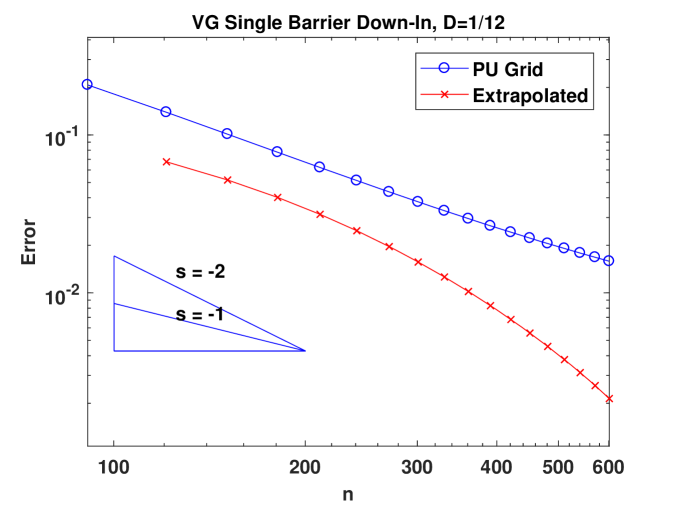

Figure 2 presents the convergence behavior of CTMC approximation for a sing-barrier down-and-in Parisian option under the BS model, Kou’s model and the VG model, respectively. In the left panel, we compare two different grids: a picewise uniform grid with on the grid and placed midway between two adjacent grid points (see (4.80)) and a uniform grid. For all three models, when the uniform grid is used, convergence is only first order. Moreover, there are big oscillations and this means Richardson’s extrapolation cannot be applied. In contrast, using the grid we design, convergence becomes second order and smooth in all the models. The results for the BS model justify our theoretical results. Although we don’t have proof for models with jumps, these numerical examples suggest that our grid design would also work for jump models. The plots in the right panel showcase the effectiveness of Richardson’s extrapolation. We also provide the numerical values for the original and extrapolated results in Table 1, 2 and 3. In Section A.4, we extend our algorithm to deal with regime-switching models. As an example, we consider the regime-switching BS model and the good performance of our method can be seen from the results in Table 4.

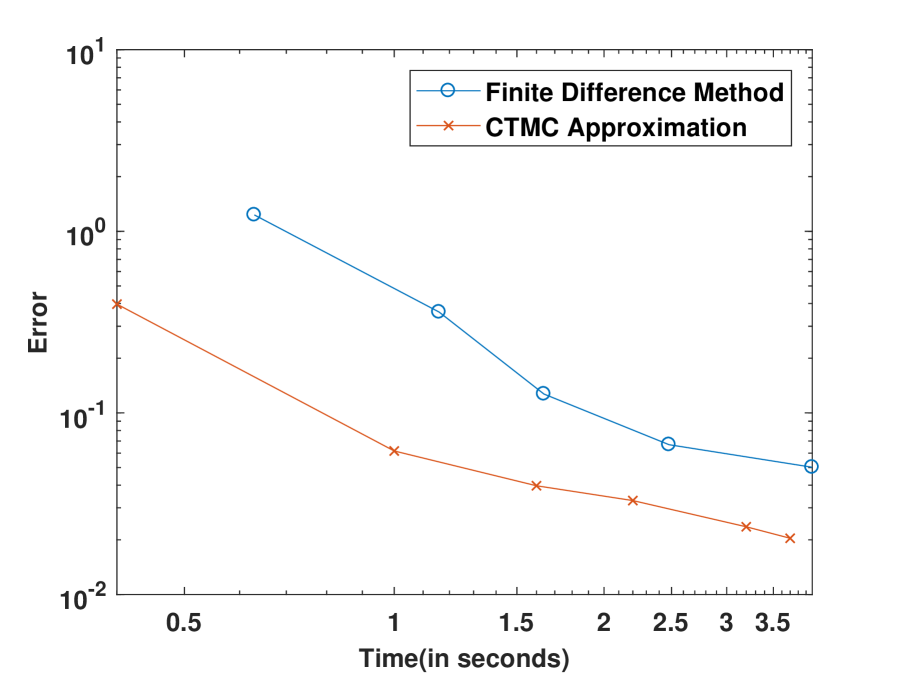

We compare our method with the explicit finite difference scheme developed in Wilmott (2013). The results are shown in Figure 3, which shows that our algorithm takes much less time (about 25% of the finite difference method) to achieve the same error level. The relatively slow performance of the finite difference approach should be expected as the PDE satisfied by the Parisian down-in option involves an additional dimension that records the length of excursion below the barrier and time discretization is required.

| Exact | CTMC | Error | Rel. Err. | Time/s | Extra. | Error | Rel. Err. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 91 | 1.97866 | 1.58183 | 3.97E-01 | 20.06% | 0.1 | |||

| 121 | 1.97866 | 1.74318 | 2.35E-01 | 11.90% | 0.2 | 1.95326 | 2.54E-02 | 1.28% |

| 151 | 1.97866 | 1.82432 | 1.54E-01 | 7.80% | 0.2 | 1.96990 | 8.76E-03 | 0.44% |

| 181 | 1.97866 | 1.87017 | 1.08E-01 | 5.48% | 0.3 | 1.97513 | 3.53E-03 | 0.18% |

| 211 | 1.97866 | 1.89839 | 8.03E-02 | 4.06% | 0.3 | 1.97701 | 1.65E-03 | 0.08% |

| Exact | CTMC | Error | Rel. Err. | Time/s | Extra. | Error | Rel. Err. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 91 | 4.55552 | 4.29302 | 2.63E-01 | 5.76% | 0.4 | |||

| 121 | 4.55552 | 4.40754 | 1.48E-01 | 3.25% | 0.5 | 4.55665 | 1.13E-03 | 0.02% |

| 151 | 4.55552 | 4.46071 | 9.48E-02 | 2.08% | 0.6 | 4.55611 | 5.90E-04 | 0.01% |

| 181 | 4.55552 | 4.48963 | 6.59E-02 | 1.45% | 0.8 | 4.55584 | 3.15E-04 | 0.01% |

| 211 | 4.55552 | 4.50709 | 4.84E-02 | 1.06% | 1.1 | 4.55573 | 2.10E-04 | 0.00% |

| Exact | CTMC | Error | Rel. Err. | Time/s | Extra. | Error | Rel. Err. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 391 | 1.05872 | 1.03818 | 2.05E-02 | 1.94% | 11.5 | |||

| 421 | 1.05872 | 1.03961 | 1.91E-02 | 1.81% | 13.8 | 1.05825 | 4.72E-04 | 0.04% |

| 451 | 1.05872 | 1.04084 | 1.79E-02 | 1.69% | 15.9 | 1.05810 | 6.19E-04 | 0.06% |

| 481 | 1.05872 | 1.04192 | 1.68E-02 | 1.59% | 17.3 | 1.05816 | 5.64E-04 | 0.05% |

| 511 | 1.05872 | 1.04286 | 1.59E-02 | 1.50% | 19.6 | 1.05793 | 7.89E-04 | 0.07% |

| Exact | CTMC | Error | Rel. Err. | Time/s | Extra. | Error | Rel. Err. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 91 | 4.30229 | 3.98449 | 3.18E-01 | 7.39% | 2.0 | |||

| 121 | 4.30229 | 4.12057 | 1.82E-01 | 4.22% | 3.4 | 4.29775 | 4.54E-03 | 0.11% |

| 151 | 4.30229 | 4.18514 | 1.17E-01 | 2.72% | 6.5 | 4.30099 | 1.30E-03 | 0.03% |

| 181 | 4.30229 | 4.22062 | 8.17E-02 | 1.90% | 9.9 | 4.30184 | 4.51E-04 | 0.01% |

| 211 | 4.30229 | 4.24215 | 6.01E-02 | 1.40% | 13.8 | 4.30213 | 1.66E-04 | 0.00% |

6 Conclusions

Our approach based on CTMC approximation is an efficient, accurate and flexible way to deal with Parisian stopping times and the related option pricing problems. It is applicable to general one-dimensional Markovian models and its convergence can be proved in a general setting. Moreover, extensions to regime-switching and stochastic volatility models as well as more complicated problems involving Parisian stopping times can be readily developed. We are also able to derive sharp estimate of the convergence rate for diffusion models. In general, convergence of CTMC approximation is first order, but we can improve it to second order with a proper grid design which places the Parisian barrier on the grid and all the discontinuities of the payoff function midway between two adjacent grid points. Such a grid can be easily constructed using a piecewise uniform structure. Our grid design also attains second order convergence in jump models as shown by the numerical examples. Furthermore, it ensures smooth convergence for both diffusion and jump models, which enables us to apply Richardson’s extrapolation to achieve significant reduction in the error. In future research, it would be interesting to develop effective hedging strategies for Parisian options based on our method.

Acknowledgements

The research of Lingfei Li was supported by Hong Kong Research Grant Council General Research Fund Grant 14202117. The research of Gongqiu Zhang was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 11801423 and Shenzhen Basic Research Program Project JCYJ20190813165407555.

Appendix A Several Extensions

In this section, we generalize our method for some more complicated situations to demonstrate the versality of our approach.

A.1 Multi-Sided Parisian Options

Define a Parisian stopping time for an arbitrary set as

| (A.1) |

If , then and if , . The multi-sided Parisian stopping time can be defined as

| (A.2) |

where is a collection of subsets of . The double-barrier case corresponds to with . We also let

| (A.3) |

Consider a finite state CTMC . For any in its state space , let . Define . Then, by the conditioning argument, we obtain

| (A.4) | ||||

| (A.5) | ||||

| (A.6) |

Let . It solves

| (A.7) |

Let , then it satisfies,

| (A.8) |

We can rewrite it as , and these two parts satisfy

| (A.9) |

and

| (A.10) |

Let . It is the solution to

| (A.11) |

Let . The solutions to the above equations are given as follows:

| (A.12) | |||

| (A.13) | |||

| (A.14) | |||

| (A.15) | |||

| (A.16) |

Then, we obtain

| (A.17) |

Now consider a multi-sided Parisian option with price . Using the arguments in the single-sided case, we can derive that the Laplace transform is given by

| (A.18) |

A.2 Mixed Barrier and Parisian Options

CTMC approximation can also be generalized to derive the joint distribution of Parisian stopping times and first passage times. For example, Dassios and Zhang (2016) introduce the so-called MinParisianHit option which is triggered either when the age of an excursion above reaches time or a barrier is crossed by the underlying asset price process . The MinParisianHit option price can be approximated as

| (A.19) |

where is a CTMC with state space and transition rate matrix to approximate the underlying price process. To price the option, it suffices to substitute by in the proof of Theorem 2.2 and find the Laplace transform of under the model . Let . Using the conditioning argument, we can show that satisfies a linear system

| (A.20) | ||||

| (A.21) | ||||

| (A.22) | ||||

| (A.23) |

where and (they are slightly different from and defined in Section 2).

We next analyze each term. For (A.20), let . It satisfies

| (A.24) |

For (A.21), let . It is the solution to

| (A.25) |

can be split as with satisfying

| (A.26) |

and satisfying

| (A.27) |

For (A.22), let . It solves

| (A.28) |

can be expressed as with satisfying

| (A.29) |

and satisfying

| (A.30) |

For (A.23), let . It solves

| (A.31) |

Let , , (they are slightly different from and defined in Section 2). The solutions to the above equations are given by

| (A.32) | |||

| (A.33) | |||

| (A.34) | |||

| (A.35) | |||

| (A.36) | |||

| (A.37) |

where . Let , which satisfies

| (A.38) |

The solution is

| (A.39) |

where and . Consider the Laplace transform

| (A.40) |

It can be obtained as

| (A.41) |

A.3 Pricing Parisian Bonds

Recently, Dassios et al. (2020) propose a Parisian type of bonds, whose payoff depends on whether the excursion of the interest rate above some level exceeds a given duration before maturity, i.e., , where is the bond maturity, is the short rate process, is the payoff function, and

| (A.42) |

Then its price can be written as,

| (A.43) |

where . We can calculate its Laplace transform w.r.t. as,

| (A.44) |

Suppose is a CTMC with state space to approximate the original short rate model (e.g., the CIR model considered in Dassios et al. (2020)). Let and and are defined as in Section A.2. Then, using the conditioning argument, we obtain

| (A.45) | ||||

| (A.46) | ||||

| (A.47) |

Let be the generator matrix of . Consider . It satisfies

| (A.48) |

where . Let . It solves

| (A.49) |

We can decomposed as with them satisfying

| (A.50) |

and

| (A.51) |

Let . It satisfies

| (A.52) |

Let , , , , , and . They can be calculated as follows:

| (A.53) | |||

| (A.54) | |||

| (A.55) | |||

| (A.56) | |||

| (A.57) | |||

| (A.58) |

We then calculate by dividing by and obtain the bond price by Laplace inversion.

A.4 Regime-Switching and Stochastic Volatility Models

Suppose the asset price for some function and a regime-switching process . The regime process , and in each regime is a general jump-diffusion. We approximate the dynamics of in each regime by a CTMC with state space . Hence, can be approximated by . The analysis of single-barrier Parisian stopping times for this type of models can be done similarly as in Section 2. Let

| (A.59) |

Let be the generator matrix of and it can be constructed as

| (A.60) |

where is the generator matrix of in regime , is the generator matrix of , stands for Kronecker product and is the identity matrix in . Let

| (A.61) |

with

| (A.62) |

where with . We can solve the Parisian problem in the same way as for 1D CTMCs. Let

| (A.63) | |||

| (A.64) | |||

| (A.65) | |||

| (A.66) | |||

| (A.67) |

where and . Then, we have

| (A.68) |

and can be found by solving this linear system,

| (A.69) |

For option pricing, let with being the Laplace transform of option prices

| (A.70) |

And then can be found as follows,

| (A.71) |

where with being an all-one vector in .

Remark A.1 (Stochastic volatility models).

Cui et al. (2018) show that general stochastic volatility models can be approximated by a regime-switching CTMC. Consider

| (A.74) |

where with . As in Cui et al. (2018), consider with and . It follows that

| (A.75) |

where is a standard Brownian motion independent of and,

| (A.76) |

with and . Then we can employ a two-layer approximation to : first construct a CTMC with state space and generator matrix to approximate , and then for each , construct a CTMC with state space and generator matrix to approximate the dynamics of conditioning on . Then, is approximated by a regime-switching CTMC where transitions on following when for each , and evolves according to its transition rate matrix .

Appendix B Proofs

Proof of Lemma 4.1.

(1) This result can be found in Proposition 1 and Corollary 1 of Zhang and Li (2019).

(2) We first apply Liouville transform to the eigenvalue problem. Let , , and and . Then the eigenvalue problem is cast in the Liouville normal form as follows (Fulton and Pruess (1994), Eqs.(2.1-2.5))

| (B.1) |

As shown in Eq.(2.13) of Fulton and Pruess (1994),

| (B.2) |

Hence the normalized eigenfunction can be recovered as

| (B.3) |

Then we start to study the sensitivities of and w.r.t. and from which we can obtain those of and w.r.t. and . Let . By Fulton and Pruess (1994), Eq.(3.7), we have

| (B.4) |

By Gronwall’s inequality, . Taking differentiation on both sides yields

| (B.5) | ||||

| (B.6) | ||||

| (B.7) | ||||

| (B.8) | ||||

| (B.9) |

Thus,

| (B.10) |

By Theorem 3.2 in Kong and Zettl (1996), we have

| (B.11) |

As in Eq.(6.11) of Fulton and Pruess (1994), . (B.5) implies . Therefore, .

Differentiating on both sides of (B.4), we obtain

| (B.12) | |||

| (B.13) | |||

| (B.14) | |||

| (B.15) |

Then there exist constants such that . Applying Gronwall’s inequality again shows

| (B.16) |

Taking differentiation w.r.t. on both sides of (B.5), (B.7), (B.9), and applying the above estimate, we can obtain

| (B.17) |

We can also derive that

| (B.18) |

Differentiating on both sides of (B.11), we obtain

| (B.19) |

Subsequently, we get

| (B.20) |

After some calculations based on the relationship between and , we obtain

| (B.21) |

and

| (B.22) |

By Proposition 2 in Zhang and Li (2019), we have , and hence it holds that

| (B.23) |

For (4.30), by Proposition 3 in Zhang and Li (2019), we have

| (B.24) |

The same proposition also shows . Thus, we obtain

| (B.25) | |||

| (B.26) | |||

| (B.27) | |||

| (B.28) | |||

| (B.29) | |||

| (B.30) | |||

| (B.31) |

The rest of the results in the second part follows from Lemma 3, Lemma 5 and Lemma 6 in Zhang and Li (2019).

Proof of Lemma 4.2.

Let and be two independent solutions to the Sturm-Liouville problem , where is strictly increasing and is strictly decreasing and they are by Theorem 6.19 in Gilbarg and Trudinger (2015). Then we can construct as

| (B.32) |

from which it is easy to see in .

Similar to Theorem 3.22 in Li and Zhang (2018), we can show that and hence we have the first equation in the lemma due to the smoothness of in . For the second one, let . For , the following holds:

| (B.33) | ||||

| (B.34) |

Therefore, for any , we get

| (B.35) |

We also have , from which we conclude that there must exist a pair of such that . In this case, we obtain

| (B.36) |

It follows that

| (B.37) |

and hence holds. Therefore, . Using the arguments for obtaining (B.31), we arrive at the second equation. ∎

Proof of Lemma 4.3.

We can construct as

| (B.38) |

where and are given in the proof of Lemma 4.2. From this expression, it is easy to deduce is in . Direct calculations show that

| (B.39) | ||||

| (B.40) |

Using these equations, we can verify

| (B.41) | |||

| (B.42) | |||

| (B.43) |

We have the following facterization for :

| (B.44) | ||||

| (B.45) |

To derive it, we use the fact that for to arrive at from the above, it should first touch , because it is a birth-and-death process.

Using the smoothness of in and , we get

| (B.46) |

Similar to the proof of Lemma 4.2, we can show . Thus, we can develop the following estimate for :

| (B.47) | |||

| (B.48) | |||

| (B.49) | |||

| (B.50) | |||

| (B.51) | |||

| (B.52) | |||

| (B.53) |

This concludes the proof. ∎

Proof of Proposition 4.1.

By Lemma 4.1, there exist constants such that

| (B.54) | |||

| (B.55) | |||

| (B.56) | |||

| (B.57) | |||

| (B.58) | |||

| (B.59) |

In the last equality, we use the fact that for some constants . Later on, we use this result directly. Using (4.30), we also obtain

| (B.60) | |||

| (B.61) | |||

| (B.62) | |||

| (B.63) | |||

| (B.64) | |||

| (B.65) | |||

| (B.66) | |||

| (B.67) |

For the last claim, we note that,

| (B.68) |

Noting that , we have . Then

| (B.69) | |||

| (B.70) |

where the interchange of summation and differentiation can be verified with the estimates of and in Lemma 4.1.

The results for and can be proved by arguments similar to those for the third part of Lemma 4.2 and the equation along with the differential equation for and eigenfunction expansion for . ∎

Proof of Proposition 4.2.

For the first and second claims, we only prove that . The other steps are almost identical to those in the proof of Proposition 4.1.

| (B.71) | |||

| (B.72) | |||

| (B.73) | |||

| (B.74) | |||

| (B.75) | |||

| (B.76) | |||

| (B.77) | |||

| (B.78) | |||

| (B.79) | |||

| (B.80) |

For the last claim, using the arguments in the proof of Proposition 4.1, we obtain . Hence, there holds that

| (B.81) | |||

| (B.82) |

where we use the equation of at the boundary and . ∎

Proof of Proposition 4.3.

By Theorem 1.4 in Athanasiadis and Stratis (1996), (4.69) admits a unique solution that belongs to . The equation for can be written in a self-adjoint form as

| (B.83) |

Multiplying both sides with and integrating from to yield

| (B.84) |

Further multiplying both sides with and integrating from to give us

| (B.85) | |||

| (B.86) |

Moreover, it is clear that satisfies

| (B.87) |

Multiplying both sides with and summing from to , we obtain

| (B.88) |

It follows that

| (B.89) | |||

| (B.90) |

Let . We have

| (B.91) | ||||

| (B.92) | ||||

| (B.93) | ||||

| (B.94) | ||||

| (B.95) | ||||

| (B.96) | ||||

| (B.97) |

The quantities in (B.92), (B.94) and (B.96) are all . For the quantity in (B.97), note that , with for , , and . Therefore,

| (B.98) | ||||

| (B.99) | ||||

| (B.100) |

By the same argument, we can show that . Putting these estimates back and letting , we deduce that there exists a constant independent of such that

| (B.101) | ||||

| (B.102) | ||||

| (B.103) | ||||

| (B.104) |

Noting the positive lower and upper bounds for , which are independent of and using the discrete Gronwall’s inequality, we conclude that there exist constants independent of such that

| (B.105) | ||||

| (B.106) |

Note that . Then, there exist constants independent of such that

| (B.107) | |||

| (B.108) |

Hence . Putting them back to (B.105) and (B.106), we have and . Therefore, holds and the proof is completed. ∎

Proof of Theorem 4.1.

The smoothness of and its limit at and value at are direct consequences of the properties of . By (4.39), (4.56) and (4.63), we have

| (B.109) | |||

| (B.110) | |||

| (B.111) | |||

| (B.112) |

Here we neglect the arguments for and for to make the equations shorter. Moreover, using (4.56) and (4.63), we obtain

| (B.113) | |||

| (B.114) | |||

| (B.115) | |||

| (B.116) |

Here we neglect the arguments for for the same reason. It follows that

| (B.117) | |||

| (B.118) | |||

| (B.119) | |||

| (B.120) |

By (4.57) and (4.42), we get and . Subsequently, we obtain

| (B.121) | |||

| (B.122) | |||

| (B.123) |

The last equality follows from (4.60). Therefore, there holds that

| (B.124) |

Then, by (4.61), we obtain

| (B.125) | ||||

| (B.126) | ||||

| (B.127) | ||||

| (B.128) |

Based on the previous estimates, we deduce

| (B.129) | |||

| (B.130) | |||

| (B.131) | |||

| (B.132) | |||

| (B.133) |

∎

Proof of Theorem 4.2.

Recall that and , which will be used below. We have

| (B.134) | |||

| (B.135) | |||

| (B.136) | |||

| (B.137) | |||

| (B.138) | |||

| (B.139) | |||

| (B.140) | |||

| (B.141) | |||

| (B.142) | |||

| (B.143) | |||

| (B.144) | |||

| (B.145) | |||

| (B.146) | |||

| (B.147) | |||

| (B.148) |

In the last to the second equality, we use the error estimate of the trapezoid rule and the smoothness of and . ∎

References

- Abate and Whitt (1992) Abate, J. and W. Whitt (1992). The Fourier-series method for inverting transforms of probability distributions. Queueing Systems 10(1-2), 5–87.

- Albrecher et al. (2012) Albrecher, H., D. Kortschak, and X. Zhou (2012). Pricing of Parisian options for a jump-diffusion model with two-sided jumps. Applied Mathematical Finance 19(2), 97–129.

- Athanasiadis and Stratis (1996) Athanasiadis, C. and I. G. Stratis (1996). On some elliptic transmission problems. In Annales Polonici Mathematici, Volume 63, pp. 137–154.

- Avellaneda and Wu (1999) Avellaneda, M. and L. Wu (1999). Pricing Parisian-style options with a lattice method. International Journal of Theoretical and Applied Finance 2(01), 1–16.

- Baldi et al. (2000) Baldi, P., L. Caramellino, and M. G. Iovino (2000). Pricing complex barrier options with general features using sharp large deviation estimates. In Monte-Carlo and Quasi-Monte Carlo Methods 1998, pp. 149–162. Springer.

- Bernard et al. (2005) Bernard, C., O. Le Courtois, and F. Quittard-Pinon (2005). A new procedure for pricing Parisian options. The Journal of Derivatives 12(4), 45–53.

- Cai et al. (2019) Cai, N., S. Kou, and Y. Song (2019). A unified framework for option pricing under regime-switching models. Working Paper.

- Cai et al. (2015) Cai, N., Y. Song, and S. Kou (2015). A general framework for pricing Asian options under Markov processes. Operations Research 63(3), 540–554.

- Chesney and Gauthier (2006) Chesney, M. and L. Gauthier (2006). American Parisian options. Finance and Stochastics 10(4), 475–506.

- Chesney et al. (1997) Chesney, M., M. Jeanblanc-Picqué, and M. Yor (1997). Brownian excursions and Parisian barrier options. Advances in Applied Probability 29(1), 165–184.

- Chesney and Vasiljević (2018) Chesney, M. and N. Vasiljević (2018). Parisian options with jumps: a maturity–excursion randomization approach. Quantitative Finance 18(11), 1887–1908.

- Cui et al. (2017) Cui, Z., J. L. Kirkby, and D. Nguyen (2017). A general framework for discretely sampled realized variance derivatives in stochastic volatility models with jumps. European Journal of Operational Research 262(1), 381–400.

- Cui et al. (2018) Cui, Z., J. L. Kirkby, and D. Nguyen (2018). A general valuation framework for SABR and stochastic local volatility models. SIAM Journal on Financial Mathematics 9(2), 520–563.

- Cui et al. (2019) Cui, Z., J. L. Kirkby, and D. Nguyen (2019). A general framework for time-changed markov processes and applications. European Journal of Operational Research 273(2), 785–800.

- Cui et al. (2018) Cui, Z., C. Lee, and Y. Liu (2018). Single-transform formulas for pricing Asian options in a general approximation framework under Markov processes. European Journal of Operational Research 266(3), 1134–1139.

- Czarna and Palmowski (2011) Czarna, I. and Z. Palmowski (2011). Ruin probability with Parisian delay for a spectrally negative Lévy risk process. Journal of Applied Probability 48(4), 984–1002.

- Dassios and Lim (2013) Dassios, A. and J. W. Lim (2013). Parisian option pricing: a recursive solution for the density of the Parisian stopping time. SIAM Journal on Financial Mathematics 4(1), 599–615.

- Dassios and Lim (2017) Dassios, A. and J. W. Lim (2017). An analytical solution for the two-sided Parisian stopping time, its asymptotics, and the pricing of Parisian options. Mathematical Finance 27(2), 604–620.

- Dassios and Lim (2018) Dassios, A. and J. W. Lim (2018). Recursive formula for the double-barrier Parisian stopping time. Journal of Applied Probability 55(1), 282–301.

- Dassios et al. (2020) Dassios, A., J. W. Lim, and Y. Qu (2020). Azéma martingales for Bessel and CIR processes and the pricing of Parisian zero-coupon bonds. Mathematical Finance 30(4), 1497–1526.

- Dassios and Wu (2008) Dassios, A. and S. Wu (2008). Parisian ruin with exponential claims. Working paper, Department of Statistics, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Dassios and Wu (2010) Dassios, A. and S. Wu (2010). Perturbed Brownian motion and its application to Parisian option pricing. Finance and Stochastics 14(3), 473–494.

- Dassios and Wu (2011) Dassios, A. and S. Wu (2011). Double-barrier Parisian options. Journal of Applied Probability 48(1), 1–20.

- Dassios and Zhang (2016) Dassios, A. and Y. Y. Zhang (2016). The joint distribution of Parisian and hitting times of Brownian motion with application to Parisian option pricing. Finance and Stochastics 20(3), 773–804.

- Eriksson and Pistorius (2015) Eriksson, B. and M. R. Pistorius (2015). American option valuation under continuous-time Markov chains. Advances in Applied Probability 47(2), 378–401.

- Feng and Linetsky (2008) Feng, L. and V. Linetsky (2008). Pricing options in jump-diffusion models: an extrapolation approach. Operations Research 56(2), 304–325.

- Fulton and Pruess (1994) Fulton, C. T. and S. A. Pruess (1994). Eigenvalue and eigenfunction asymptotics for regular Sturm-Liouville problems. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 188(1), 297–340.

- Gilbarg and Trudinger (2015) Gilbarg, D. and N. S. Trudinger (2015). Elliptic partial differential equations of second order. springer.

- Haber et al. (1999) Haber, R. J., P. J. Schönbucher, and P. Wilmott (1999). Pricing Parisian options. Journal of Derivatives 6, 71–79.

- Jacod and Shiryaev (2013) Jacod, J. and A. Shiryaev (2013). Limit Theorems for Stochastic Processes. Springer.

- Kim and Lim (2016) Kim, K.-K. and D.-Y. Lim (2016). Risk analysis and hedging of Parisian options under a jump-diffusion model. Journal of Futures Markets 36(9), 819–850.

- Kong and Zettl (1996) Kong, Q. and A. Zettl (1996). Dependence of eigenvalues of sturm–liouville problems on the boundary. Journal of Differential Equations 126(2), 389–407.

- Kou and Wang (2004) Kou, S. G. and H. Wang (2004). Option pricing under a double exponential jump diffusion model. Management Science 50(9), 1178–1192.

- Labart (2010) Labart, C. (2010). Parisian option. Encyclopedia of Quantitative Finance.

- Le et al. (2016) Le, N. T., X. Lu, and S.-P. Zhu (2016). An analytical solution for Parisian up-and-in calls. The ANZIAM Journal 57(3).

- Li and Zhang (2018) Li, L. and G. Zhang (2018). Error analysis of finite difference and Markov chain approximations for option pricing. Mathematical Finance 28(3), 877–919.

- Loeffen et al. (2013) Loeffen, R., I. Czarna, Z. Palmowski, et al. (2013). Parisian ruin probability for spectrally negative Lévy processes. Bernoulli 19(2), 599–609.

- Lu et al. (2018) Lu, X., N.-T. Le, S. P. Zhu, and W. Chen (2018). Pricing American-style Parisian up-and-out call options. European Journal of Applied Mathematics 29(1), 1–29.

- Madan et al. (1998) Madan, D. B., P. P. Carr, and E. C. Chang (1998). The variance gamma process and option pricing. Review of Finance 2(1), 79–105.

- Mijatović and Pistorius (2013) Mijatović, A. and M. Pistorius (2013). Continuously monitored barrier options under Markov processes. Mathematical Finance 23(1), 1–38.

- Song et al. (2018) Song, Y., N. Cai, and S. Kou (2018). Computable error bounds of Laplace inversion for pricing Asian options. INFORMS Journal on Computing 30(4), 634–645.

- Wilmott (2013) Wilmott, P. (2013). Paul Wilmott on quantitative finance. John Wiley & Sons.

- Zhang and Li (2019) Zhang, G. and L. Li (2019). Analysis of Markov chain approximation for option pricing and hedging: grid design and convergence behavior. Operations Research 67(2), 407–427.

- Zhang and Li (2021a) Zhang, G. and L. Li (2021a). Analysis of Markov chain approximation for diffusion models with non-smooth coefficients for option pricing. Available at SSRN 3387751.

- Zhang and Li (2021b) Zhang, G. and L. Li (2021b). A general method for analysis and valuation of drawdown risk under Markov models.

- Zhang et al. (2021) Zhang, X., L. Li, and G. Zhang (2021). Pricing American drawdown options under Markov models. European Journal of Operational Research 293(3), 1188–1205.

- Zhu and Chen (2013) Zhu, S.-P. and W.-T. Chen (2013). Pricing Parisian and Parasian options analytically. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 37(4), 875–896.