An elementary multidimensional fundamental theorem of calculus

Abstract.

We discuss a version of the fundamental theorem of calculus in several variables and some applications, of potential interest as a teaching material in undergraduate courses.

Key words and phrases:

Integral; Derivative; Interval Functions; Density2020 Mathematics Subject Classification:

Primary: 26B05; Secondary: 26A24; 26B30; 28A10; 28A15.1. Introduction and main result

In standard undergraduate courses on one variable calculus, differentiation and integration are presented as inverse processes, as stated in the fundamental theorem of calculus: if is differentiable at every point and is integrable in , then

This holds both in the context of Riemann and Lebesgue integration (see [4] for a proof in the Lebesgue integration context).

In this note we provide a multidimensional version of this statement. The proof is straightforward and can be included in an undergraduate course of multidimensional calculus.

The first basic concept is that of interval or cube function on a domain . By an interval in we understand a set with the , a one-dimensional closed interval, that is the faces of are parallel to the coordinate axis. An interval function is a map defined on all intervals assigning to each a real or complex number with the property that

whenever is a finite partition of , that is, and the have disjoint interiors. The easiest example is

where is locally integrable.

We have in mind two other examples. For the first one, assume that is a measurable homeomorphism between two domains such that if . Here and in the following denotes the Lebesgue measure of . Then is an interval function, because images of the faces have zero measure. For the second one assume that is a continuous vector field in the plane or in space and set

the flow of through the boundary oriented with the outward normal . Then is an interval function. This is because if are two intervals with a face in common, the outward normals are opposite one each other.

Notice that a Dirac delta at a point , that is, if and zero otherwise, is not an interval function according to our definition, because if is a boundary point of both then .

In dimension , with , if is defined on , it is immediately seen that

| (1) |

defines an interval function on . Indeed, a decomposition of into pieces amounts to a selection of intermediate points (the end-points of the ) , and then

Conversely, given an interval function defined on and , the function

satisfies (1). Thus there is a one-to-one correspondence between interval functions and classical functions.

The second basic concept is that of density. For an interval function we define its upper density

where denotes the measure of and its diameter. Analogously the lower density is defined

In case both are finite and equal we say that has a finite density at .

For instance, if is continuous in , the density of is at all points. Indeed, given there is such that if . Then, if one has for all so

Thus

A deeper result is Lebesgue’s differentiation theorem (see [3]) stating that has density at almost all points under the sole assumption that is locally integrable.

For a better understanding of the density consider the following example. Assume and let be the diagonal. Define as the length of , clearly an interval function. Then for while for .

In dimension one, if is given by , has a finite density at if and only is differentiable at , because if

Next elementary theorem seems to be unnoticed, to the best of author’s knowledge. It holds both in the context of Riemann and Lebesgue’s integration.

Theorem 1.1.

If an interval function has a finite upper density at every point and is locally integrable, then for every cube

Analogously, if has a finite lower density at every point and is locally integrable, then

Thus,

whenever has a finite integrable density at every point.

In an informal way, if is of the order of for infinitesimal cubes , then for big cubes.

In dimension one, in view of the remark before the theorem, this is the fundamental theorem of calculus stated in the beginning.

As a corollary we may state:

Corollary. For an interval function and a continuous function on the following two statements are equivalent:

We point out some remarks. First, it is essential, as in one variable, that the density is assumed to exist at every point. If it exists just a.e. then the theorem does not hold. Secondly, in other type of results the a.e. existence of the density is actually proved like in Lebesgue’s differentiation theorem quoted before. In fact, the interval functions are characterized as those being absolutely continuous, meaning that for every there exists such that whenever are non-overlapping cubes and . So the result can be rephrased by saying that interval functions having finite integrable density at all points are automatically absolutely continuous. A reference for all these results is [3].

2. Proof

Let be a cube and let us break it into cubes of equal measure. Since , one has

whence

for at least one . Repeating the argument we find a sequence of cubes, , shrinking to some point such that

Therefore . So for some point . Similarly, for some point. This holds for all cubes. So if . Similarly, if .

We complete now the proof in the Riemann integration context, where just the definition of the Riemann integral is used.

Let be a partition of ; then

Therefore, if is Riemann integrable, it follows that

In a similar way we see that

and so the theorem is proved when the density is Riemann integrable.

Assume now that is Lebesgue integrable on . We may assume real-valued and use semi-continuous functions as in [4]. Recall that a function is called lower semi-continuous at a point if and upper semi-continuous if .

Given , by the Vitali-Carathedory theorem, there is a lower semi-continuous function such that and . Define

Then, being lower semi-continuous,

Therefore , whence

Since is arbitrary, this shows that and applying the same argument to we are done.

3. Applications

1. As a first application we indicate a simplified proof of a version of the change of variables formula, with minimal assumptions and not relying in the one-dimensional version and Fubini’s theorem, the one stated in Theorem 7.26 in [4]:

Theorem 3.1.

Let be an homeomorphism between two domains in , differentiable at every point . Assume that is integrable on . Then for a positive measurable function in one has

| (2) |

Note that the assumption is not made, so this version includes Sard’s theorem.

We modify the proof in [4] replacing the more advanced Radon-Nikodym differentiation theorem for absolutely continuous measures by theorem 1.1.

First, Lemma 7.25 in [4] proves that maps sets of measure zero to sets of measure zero. As a consequence,

is an interval function.

Secondly, theorem 7.24 in [4] proves that has density at every point . In fact, the proof in [4] uses balls, but it is easily checked that it holds for cubes too. We explain the basic idea for completeness. By hypothesis, we can approximate near by , and use that for all affine maps.

One has

with decreasing as .

Let be the columns of . If has side , maps onto a parallelepiped with spanning vectors , whose measure is

so let us compare with . Since , it is clear that is included in a parallelepiped concentric with with spanning vectors , whose measure is

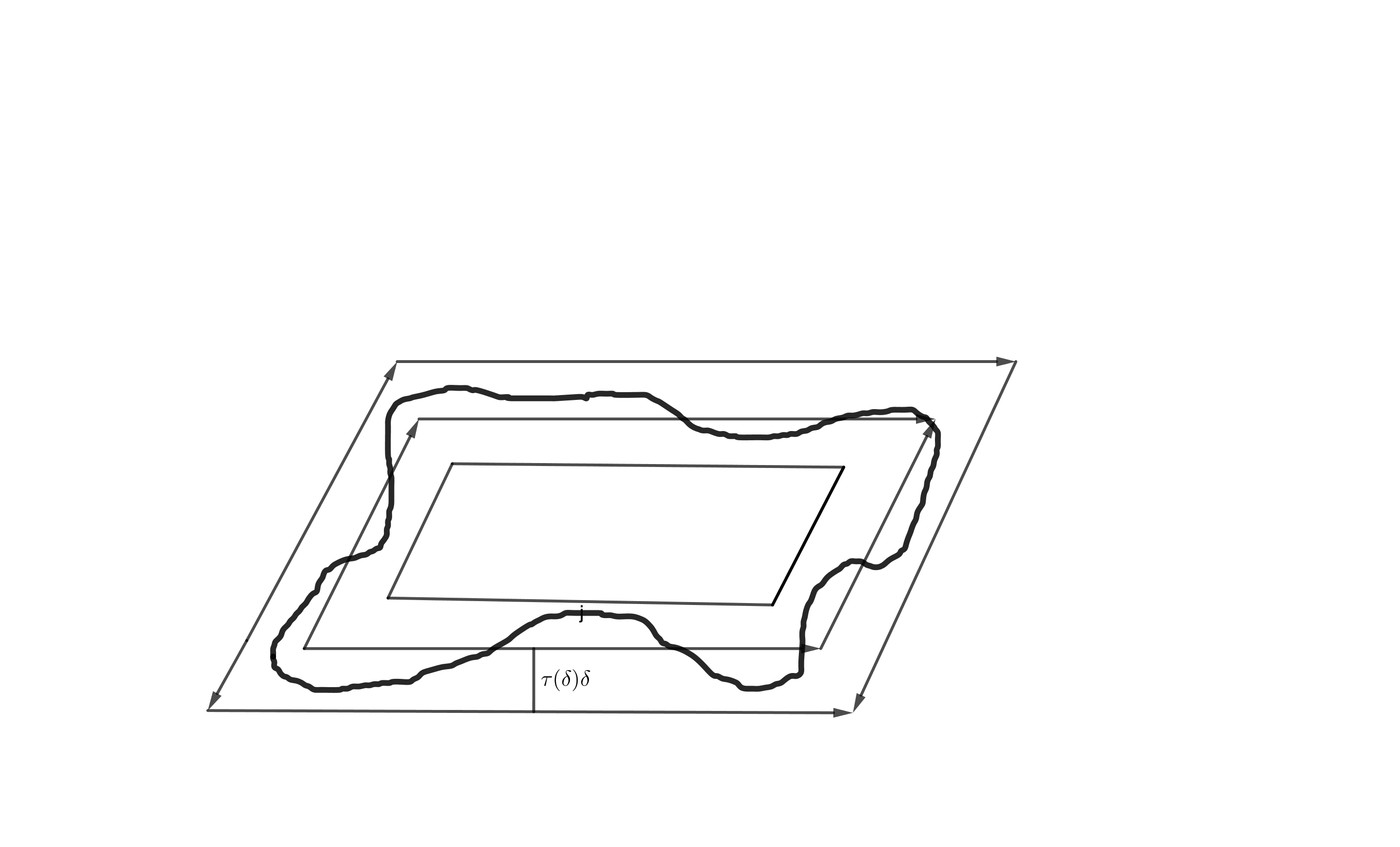

Again by , the boundary is at distance less than from . Since is an homeomorphism, this implies that contains a parallelepiped concentric with with spanning vectors (see figure 1 for ; a rigorous proof of this fact relies on Brouwer’s fixed point theorem and can be found in lemma 7.23 of [4]), whose measure is

Altogether, since ,

proving that has density at .

By theorem 1.1, one has

when is a cube, whence when is a finite union of cubes too. Since every open set is a countable union of cubes, by the monotone convergence theorem this holds when is an open set and in turn when is a countable intersection of open sets, a set. Since every measurable set differs from s set in a set of zero measure and preserves those, we conclude that this holds for all measurable sets , that is, (2)holds for the characteristic function of a measurable set. By linearity it then holds for simple functions, and by the monotone convergence theorem again, for a general measurable function.

Remark. As a first remark for the instructor, in case for all , the use of Brouwer’s fixed point theorem can be avoided as follows:

By the inclusion ,

implying . Then theorem 1.1 implies

for all cubes, and as before this leads to

But since the same inequality applies to the inverse , the result follows.

Remark. As a second remark, to be eventually combined with the previous one, a proof in the context of Riemann integration can be further simplified as follows. To prove (2) say for a continuous function with compact support, introduce

The continuity of implies

so . This leads using theorem 1.1 to

for all cubes. If is the support of , the compact can be covered by a finite number of cubes , so (2) follows.

2. As a second application we analyze the divergence theorem. Assume that is a continuous vector field in space and set

the flow of through the boundary oriented with the outward normal . We mentioned before that is indeed an interval function. If its density exists, we call it the divergence of . If integrable, the theorem implies

and the same holds with replaced by a finite union of cubes. From this it follows by approximations that the same holds with replaced by a domain with piece-wise regular boundary (details can be found in [1]).

If is differentiable with components , let us check that the density exists at every point and equals .

First consider an affine field , where is a constant matrix and are the column vectors , and let us compute the flux across the boundary of a parallelepiped in space spanned by vectors

containing , oriented by the outward normal. differs from by a constant field, which obviously has zero flux, so we can replace by and assume . On the face , the basis is positively oriented and the flux is

while on the face it is

Therefore they add up to

If , this equals . The same applies to the other two couples of opposite sides, whence the flux is exactly

the trace of times the volume of .

Now let be a differentiable field at , a cube of size containing . As before we expand around

The contribution to the flux of across of the constant field is zero, that of the linear field is the trace of times while that of is , whence the flux equals

thus proving that the density is .

Upon replacement of the field by the divergence theorem in the plane amounts to Green’s formula. Using the language of line integrals, if is a differentiable -form and is integrable one has

with no assumption needed separately for . A particular case are complex line integrals

for continuous in the complex plane . For differentiable the density is , and so if integrable one has

Other general versions of Green’s theorem with minimal assumptions are known, but the proofs are far from elementary (see [2] and references herein).

3. In a surface in oriented by a unit normal field one can define cubes as those which are so in a local chart. If is a continuous field, the circulation

defines an interval function. If is differentiable, one can show along the same lines that the density is and one gets Stoke’s theorem with minimal assumptions (see the details in the book [1]).

Acknowledgements

The author is partially supported by the Ministry of Science and Innovation–Research Agency of the Spanish Government through grant PID2021-123405NB-I00 and by AGAUR, Generalitat de Catalunya, through grant 2021-SGR-00087. The author thanks his colleague Julià Cufí for valuable comments.

References

- [1] J. Bruna, Analysis in Euclidean Space, Essential Textbooks in Mathematics, World Scientific, November 2022

- [2] R.M. Fesq, Green’s formula, linear continuity, and Hausdorff measure. Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 118 (1965), 105-112.

- [3] S. Lojasiewicz, An introduction to the theory of real functions, Wiley-Interscience, 1988.

- [4] W. Rudin, Real and Complex Analysis, Mc Graw-hill, 1987.