Avatar Communication Provides More Efficient Online Social Support Than Text Communication

Abstract

Online communication via avatars provides a richer online social experience than text communication. This reinforces the importance of online social support. Online social support is effective for people who lack social resources because of the anonymity of online communities. We aimed to understand online social support via avatars and their social relationships to provide better social support to avatar users. Therefore, we administered a questionnaire to three avatar communication service users (Second Life, ZEPETO, and Pigg Party) and three text communication service users (Facebook, X, and Instagram) (). There was no duplication of users for each service. By comparing avatar and text communication users, we examined the amount of online social support, stability of online relationships, and the relationships between online social support and offline social resources (e.g., offline social support). We observed that avatar communication service users received more online social support, had more stable relationships, and had fewer offline social resources than text communication service users. However, the positive association between online and offline social support for avatar communication users was more substantial than for text communication users. These findings highlight the significance of realistic online communication experiences through avatars, including nonverbal and real-time interactions with co-presence. The findings also highlighted avatar communication service users’ problems in the physical world, such as the lack of offline social resources. This study suggests that enhancing online social support through avatars can address these issues. This could help resolve social resource problems, both online and offline in future metaverse societies.

Introduction

Social support improves mental health Cohen and Wills (1985); Rothon et al. (2011). This is also true online (online social support) Mesch and Talmud (2006); Chung (2013); Choudhury and De (2014); Trepte, Dienlin, and Reinecke (2015); Cole et al. (2017); Sharma and De Choudhury (2018); Reblin et al. (2018); Takano and Tsunoda (2019); Yokotani and Takano (2021a); Pierce et al. (2020); Takano and Yokotani (2022). Online social support is particularly practical for people who lack social resources because of the anonymity of online communities Kang, Dabbish, and Sutton (2016); Choudhury and De (2014). Detailed disclosure facilitates the reception of greater social support in cases of negative experiences and emotions Choudhury and De (2014). The characteristics of online communication facilitate disclosure Kang, Dabbish, and Sutton (2016); Choudhury and De (2014) by decreasing listeners’ fears of rejection Mesch and Talmud (2006); Küster, Krumhuber, and Kappas (2015); Andalibi et al. (2016). This is helpful that people face issues that are difficult to disclose in the physical world owing to stigma and prejudice (sexual minorities Yokotani and Takano (2021a), bullying victimization Cole et al. (2017); Takano and Tsunoda (2019); Takano and Yokotani (2022), sexual abuse Andalibi et al. (2016), suicidal feelings Choudhury and De (2014), and mental health problems Sharma and De Choudhury (2018)).

Nonverbal communication is essential for social support because socioemotional cues play a crucial role in emotional support and are conveyed nonverbally Mehrabian (1970); Manusov and Patterson (2006). Previous studies Ledbetter and Larson (2008); Trepte, Dienlin, and Reinecke (2015); McCloskey et al. (2015) have highlighted the lack of nonverbal communication in online text communication. Interactions using online tools are less satisfactory than face-to-face interactions Kock (2005); Vlahovic, Roberts, and Dunbar (2012). Although people have invented emotional expressions under the constraints of text media, such as emoticons and emojis, the effects of online social support are limited Ledbetter and Larson (2008); Trepte, Dienlin, and Reinecke (2015); McCloskey et al. (2015).

By contrast, avatar communication, in which individuals with virtual bodies can display facial expressions and gestures in a virtual space, enables nonverbal and real-time interactions with online co-presence Antonijevic (2008); Green-Hamann, Campbell Eichhorn, and Sherblom (2011); O’Connor et al. (2015); van der Land et al. (2011). Avatar actions realize emotional expressions when talking about bullying in the physical world, such as the painfulness of bullying and empathy for painfulness, in the avatar communication application Pigg Party Takano and Tsunoda (2019). In the metaverse, users’ social presence tends to increase because of the avatar’s spatial presence van der Land et al. (2011). Oh et al. (2023) indicated that a high social presence increases online social support, which mitigates loneliness in two metaverse platforms (ZEPETO and Roblox). Proxemic behavior in the online virtual world game Second Life has been observed to evoke feelings similar to those experienced in the physical world Antonijevic (2008) and to facilitate communication in social support groups (alcoholics anonymous and cancer caregivers) Green-Hamann, Campbell Eichhorn, and Sherblom (2011). These avatar communication features provide improved social support Green-Hamann, Campbell Eichhorn, and Sherblom (2011); Takano and Yokotani (2022).

Therefore, online social support through avatars is necessary for those who lack social resources in the physical world. Online social support will play an essential role in future metaverse societies. We aimed to understand online social support via avatars and their social relationships to provide better social support to avatar users. We compared three avatar communication services (Second Life, ZEPPETO, and Pigg Party) with three text communication services (Facebook, X, and Instagram).

While there are several previous studies for online social support, most of them focus on a single application (E-mail: Ledbetter and Larson (2008), Reddit: Choudhury and De (2014); Andalibi et al. (2016); Sharma and De Choudhury (2018), Facebook: McCloskey et al. (2015), World of Warcraft: O’Connor et al. (2015), Second Life: Antonijevic (2008); Green-Hamann, Campbell Eichhorn, and Sherblom (2011), Pigg Party: Takano and Tsunoda (2019); Yokotani and Takano (2021a); Takano and Yokotani (2022)) or compare text communication applications with each other (Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and Twitter Phua, Jin, and Kim (2017)) or avatar communication applications with each other (ZEPETO and Roblox Oh et al. (2023)). As far as the authors know, no studies compare multiple avatar and text communication applications on the same basis. Although there have been studies examining the effects of text and avatars on self-disclosure in controlled environments using applications developed specifically for psychological experiments Yuan et al. (2025), there is a lack of research investigating self-disclosure and social support on applications used in everyday life. In this context, two significant gaps need to be addressed: First, how do social relationships differ quantitatively between text-based communication applications and avatar-based communication applications? Second, despite their unique specifications, design, and user types, are there common characteristics shared within every kind of application? For these research gaps, the comparison between the two types of applications can provide essential insights into the perspective of generalizing the findings from previous research.

First, we examine the following hypotheses:

-

•

H1: Online social support is practical in avatar communication services compared with text communication services.

Second, we considered the stability of the relationships in each communication service. Real-time interaction with online co-presence in avatar communication Antonijevic (2008); Green-Hamann, Campbell Eichhorn, and Sherblom (2011); O’Connor et al. (2015) restricts the time and online location compared with asynchronous text communication because avatar communication requires users to be in the same place simultaneously for communication. This indicates that they have stable social relationships. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

•

H2: The users of avatar communication services have stable relationships compared with text communication services.

Examining this hypothesis is important for understanding online social support features via avatars because stable relationships are essential for social support. Stable and close relationships provide rich social support Westmyer and Myers (2009); Kendrick, Jutengren, and Stattin (2012); Roberts et al. (2014), and several relationships offer opportunities to receive social support. In addition, online social support can be reinforced in virtual worlds by improving online ego network structures Pérez-Aldana et al. (2021); Takano and Yokotani (2022). People tend to disclose their emotions and sensitive information in a closed cyberspace with friends (not strangers) Jaidka, Guntuku, and Ungar (2018); Takano and Tsunoda (2019).

Third, we focused on the relationship between online and offline social support. Positive correlations have been frequently observed between online and social support in the physical world (offline social support) Trepte, Dienlin, and Reinecke (2015); Lin et al. (2018); Takano and Yokotani (2022). This finding is significant because it suggests that online social support enhances social support in the physical world McKenna and Bargh (1998); Lin et al. (2018); Thomas, Orme, and Kerrigan (2020). This is because receiving online social support facilitates offline social activities, thereby increasing the number of relationships that provide offline social support Lin et al. (2018). Consequently, high levels of social support in the virtual world can mitigate loneliness by mediating social support in the physical world Thomas, Orme, and Kerrigan (2020) and might decrease bullying victimization. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

•

H3: The users of avatar communication services have offline social resources (high offline social support, low loneliness, and less likely to be bullied) if H1 is true.

The contributions of this study are as follows:

-

•

This is the first study comparing multiple avatar and text communication applications on the same basis.

-

•

Avatar communication service users received more online social support than text communication service users (H1 was supported).

-

•

They maintained more stable social relationships than text communication service users (H2 was supported).

-

•

They had fewer offline social resources than text communication service users (H3 was not supported), i.e., their social resources tended to be lacking.

-

•

Their association between online and offline social resources was higher than that of text communication users. This suggests that improving their online social support may solve the problem of a lack of offline social resources.

We expect to contribute to the resolution of social resource problems in future metaverse societies.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from a panel managed by Cross Marketing, Inc., consisting of individuals living in Japan. The survey was conducted in Japan and administered in Japanese, so most participants were presumed to be native Japanese speakers residing in Japan. Thus, the impact of cultural differences arising from the regions of the application providers (for example, Zepeto in South Korea and Pigg Party in Japan) on the analysis results seems small. First, they answered questions about the services they used and their frequency of use from the three avatar communication services and three social media/social networking services. If they used any of the services at least once a month, they were assigned to one of them and answered the items described later. There was no duplication of users for each service. Participants were equally divided in terms of age and gender. Table 1 summarizes the basic statistics of each service.

| Service | Gender | N | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Life | Female | 522 | 38.56 | 11.30 |

| Male | 960 | 45.21 | 12.15 | |

| Other | 13 | 34.46 | 13.57 | |

| ZEPETO | Female | 584 | 38.98 | 12.38 |

| Male | 890 | 44.78 | 11.45 | |

| Other | 17 | 37.88 | 12.82 | |

| Pigg Party | Female | 605 | 38.87 | 11.72 |

| Male | 869 | 45.66 | 12.21 | |

| Other | 19 | 42.68 | 12.82 | |

| Female | 619 | 46.82 | 12.69 | |

| Male | 859 | 48.35 | 12.53 | |

| Other | 3 | 28.00 | 7.21 | |

| X | Female | 697 | 39.43 | 13.36 |

| Male | 787 | 40.19 | 12.17 | |

| Other | 7 | 30.71 | 6.52 | |

| Female | 1,017 | 38.45 | 13.26 | |

| Male | 472 | 40.34 | 13.64 | |

| Other | 7 | 41.14 | 15.91 | |

| Total | - | 8,947 | 42.20 | 12.90 |

Communication Services

Avatar Communication Services

1

We surveyed users of three metaverse/avatar communication services: Second Life, ZEPETO, and Pigg Party (Fig. 1). This allows them to create avatars, explore virtual worlds, and interact with others through their avatars using text and voice chats. Second Life provides realistic 3D avatars, Pigg Party provides fancy 2D avatars, and ZEPETO provides an intermediate between the two avatars. Several researchers have studied human behavior in the metaverse and gained various insights based on data from Second Life: Antonijevic (2008); Green-Hamann, Campbell Eichhorn, and Sherblom (2011); Greiner, Caravella, and Roth (2014); Mitra and Golz (2016); Messinger et al. (2019), ZEPETO: Lee, Lee, and Bae (2023); Aris et al. (2023); Ko and Kim (2024); Hur and Baek (2024); Lee et al. (2024), and Pigg Party: Takano and Tsunoda (2019); Yokotani and Takano (2021a); Takano and Yokotani (2022); Yokotani and Takano (2022); Yokotani, Takano, and Abe (2024).

Second Life, operated by Linden Research, Inc. (US), has provided metaverse services since 2003. It has approximately 900,000 active monthly users111https://nwn.blogs.com/nwn/2020/06/sl-mau-pandemic-june-2020.html. In 2009, 1.3% of its users were Japanese222https://www.itmedia.co.jp/news/articles/0703/07/news074.html.

ZEPETO, operated by Naver Z (South Korea), is a metaverse application launched in 2018. It boasts of 20 million monthly active users333https://www.kedglobal.com/metaverse/newsView/ked202203040009, 70% of whom are females aged from 10 to early 20s. Japanese users are estimated to comprise 5–10% of the total user base444https://xtrend.nikkei.com/atcl/contents/casestudy/00012/00921/.

Pigg Party is a social avatar community app operated by CyberAgent, Inc. (Japan), which was launched in 2015. A previous study reported on at least 550,000 active players over six months Yokotani and Takano (2021b). Pigg Party players were predominantly young women, with a female ratio of 61% and a teenage ratio of 65% Takano and Tsunoda (2019).

Text Communication Services

We conducted a survey with X, Facebook, and Instagram users as major social media and social networking services. These services provide three types of communication methods (sending direct messages, posting one’s feed, and replying to posts). Each service has hundreds of millions of users. Several researchers have studied online human behavior in these services.

Measure

Perceived Online/Offline Social Support

We examined two types of social support (emotional and instrumental) Fukuoka and Hashimoto (1997) and three sources of social support (family, offline friends, and online friends) because these types and sources influence the buffering effects of social support on mental health Malecki and Demaray (2003); Semmer et al. (2008); Rothon et al. (2011); McCloskey et al. (2015); Oriol et al. (2017); Wills and Shinar (2015); Trepte, Dienlin, and Reinecke (2015); Liu, Wright, and Hu (2018). We categorized family and offline friends as sources of offline social support and online friends as sources of online social support.

We classified social support into emotional and instrumental support Declercq et al. (2007); Shakespeare-Finch and Obst (2011); Tsuboi, Hirai, and Kondo (2016); Obst et al. (2019). This classification is the most comprehensive despite the availability of various definitions of social support Shakespeare-Finch and Obst (2011); Obst et al. (2019).

In addition to online friends as sources of social support, we considered the relationships between recipients and sources, including family and offline friends. These relationships are broadly applicable across different contexts, unlike teachers and classmates, who are specific to student surveys. We selected these types because the participants had diverse backgrounds.

We performed a confirmatory factor analysis using maximum likelihood estimation for this perceived social support scale. Cronbach’s values for emotional and instrumental social support from family were and , those from offline friends were and , and those from online friends were and , respectively.

In this study, we used the results of a principal component analysis (PCA) for perceived emotional and instrumental social support for each source type according to a previous study Takano and Yokotani (2022). This approach was selected because emotional and instrumental support are often highly correlated Semmer et al. (2008); Shakespeare-Finch and Obst (2011); Tsuboi, Hirai, and Kondo (2016); Obst et al. (2019); Takano and Yokotani (2022), which can lead to multicollinearity in mental health regression analyses Tsuboi, Hirai, and Kondo (2016). The correlations between the two types of social support were (family), (offline friends), and (online friends).

The PCA identified the same two principal components of social support: family, offline friends, and online friends. The first principal component represented the overall strength of perceived social support by integrating the two types of social support. For all social support sources, the coefficient of this component was . The second principal component represented the relative strength of perceived emotional support compared to perceived instrumental support. For all social support sources, the coefficient of this component was . The first principal component was used to represent the strength of perceived social support.

Online Relational Mobility

Yuki et al. (2007) developed a scale to measure relational mobility or the general number of opportunities to form new relationships, when necessary, in a given society or social context. They identify two factors in meeting new people and selecting interaction partners for relational mobility. We used meetings with new people on each online communication service to measure online relational mobility. This would be negatively correlated with the stability of social relationships. We performed a confirmatory factor analysis using the maximum likelihood estimation of this scale. Cronbach’s value for online relational mobility was .

Loneliness

Bullied Experience in the Physical World

We used a Japanese bully/victim questionnaire Yokotani and Takano (2021a) based on the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire Olweus (1996) to evaluate offline victimization. We performed a confirmatory factor analysis using the maximum likelihood estimation of this scale. The Cronbach’s value for offline victimization was .

Control Variables

The participants provided their demographic information (gender (female, male, and others) and age (18 years or older) and usage frequency of services (six levels: almost every day, 4–5 days per week, 2–3 days per week, a day per week, 2–3 days per month, and a day per month). These were used as control variables.

Ethics Approval Statement

This study was approved by the ethics committee of CyberAgent, Inc (CAE-2023-07). All procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines for studies involving human participants and the ethical standards of the Institutional Research Committee.

Participants provided informed consent to participate in the survey and could stop at any time (refer to Fig. A1). Participants were also allowed to withdraw their responses after completing the survey. This informed consent form included an inquiry contact form for requests for disclosure and withdrawal of responses.

Quantitative data outputs are presented at the aggregate level, indicating that no identifying information is presented.

Results

We revealed the features of the social relationships of avatar communication services compared with text communication services.

Perceived Online Social Support (H1)

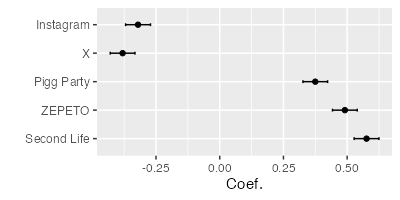

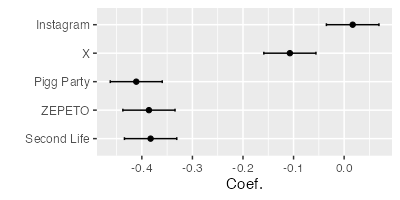

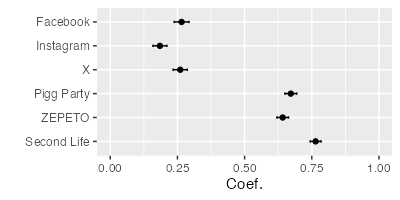

To examine H1, we compared perceived online social support between avatar and text communication service users. Fig. 2 shows the results of variance (ANOVA) for perceived online social support with controlling age, gender, and usage frequency, where Facebook was used as the reference category (that is, shows Facebook). All avatar communication service users displayed more online social support than text communication users. Refer to Table A1 in the appendix for the statistical tests. We also obtained the following ANOVA results in the same settings:

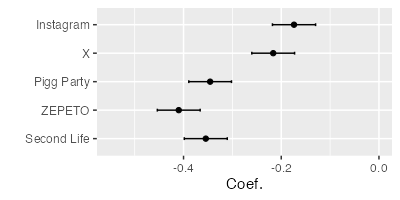

Online Relational Mobility (H2)

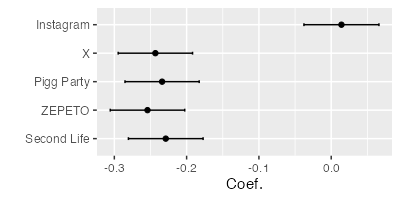

To examine H2, we compared online relational mobility between avatar and text communication service users. Fig. 3 shows the results of ANOVA for online relational mobility while controlling for age, gender, and usage frequency. All avatar communication service users exhibited lower online relational mobility than text communication service users; specifically, they had more stable relationships than text communication service users. See Table A2 in the appendix for the statistical tests.

Offline Social Support, Loneliness, and Bullying Victimization (H3)

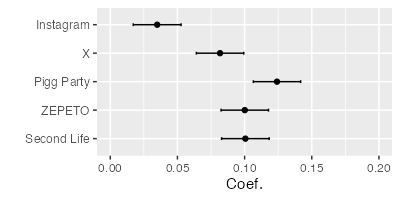

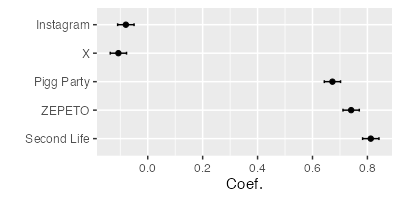

To examine H3, we compared perceived social support from social relationships in the physical world (family and offline friends), loneliness, and bullying victimization between avatars and text communication service users. Figs. 4, 5, 6, and 7 show the result of ANOVA for perceived social support from family and offline friends, loneliness, and bullying victimization, respectively, after controlling for age, gender, and usage frequency. Refer to Tables A3, A4, A5, and A6 in the appendixes for statistical tests. Avatar communication service users displayed less social support from family and offline friends, more loneliness, and more victimization than text communication users, excluding X user’s social support from offline friends and X users’ loneliness. In contrast to H3, the social resources for avatar communication users are lacking. Note that X users were also lacking compared with Facebook and Instagram users.

Association Between Online Social Support and Offline Social Support

The above analysis suggests a negative association between online and offline social support inter-services. To mitigate the lack of offline social resources, we analyzed the association between online and offline social support intra-services.

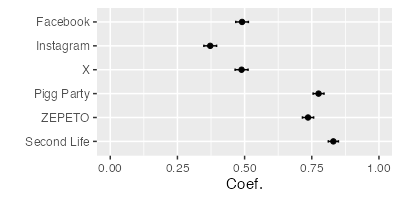

Figs. 8 and 9 show the coefficient of regression for each service, where independent variables were social support from family and offline friends, and the dependent variable was online social support, with controlling age, gender, and usage frequency. Refer to Tables A7 and A8 in the Appendix for the statistical tests.

All the services exhibited positive associations between online and offline social support. Avatar communication services exhibit stronger associations than text communication services.

Discussion

We examined three hypotheses to understand the characteristics of online social support via avatars by comparing them with text communication services.

Avatar communication users perceived online social support more than text communication services. H1 was supported. This suggests that the similarity of communication via avatars to face-to-face communication (nonverbal expressions, real-time interaction, and co-presence Antonijevic (2008); Green-Hamann, Campbell Eichhorn, and Sherblom (2011); O’Connor et al. (2015)) is essential for online social support and that social relationships in avatar communication services are suited to online social support. This is because these characteristics contribute to conveying emotions and facilitate social support Antonijevic (2008); Green-Hamann, Campbell Eichhorn, and Sherblom (2011); Takano and Tsunoda (2019). Although online communication is inferior in terms of emotional interaction and social support Kock (2005); Ledbetter and Larson (2008); Vlahovic, Roberts, and Dunbar (2012); Trepte, Dienlin, and Reinecke (2015); McCloskey et al. (2015), avatar communication may eliminate this issue.

Avatars can enhance online social support Green-Hamann, Campbell Eichhorn, and Sherblom (2011); Takano and Yokotani (2022). Takano and Tsunoda (2019) analyzed bullying consultation conversations on Pigg Party, highlighting online social support through avatars. The study found that bullying victims often used avatar actions to express emotions and self-disclose. Recipients also used emotional expressions through text and avatars. For instance, victims used words like “distress,” “cutting-off,” and “suicidal feelings,” along with avatar actions like “wailing” to show their suffering. Listeners responded with similar words and avatar actions to show empathy.

Avatar communication users had more stable relationships than text communication service users; that is, H2 was supported. This seems to be because the characteristics of avatar communication (real-time interaction with online co-presence Antonijevic (2008); Green-Hamann, Campbell Eichhorn, and Sherblom (2011); O’Connor et al. (2015)) require simultaneous communication. Such stable relationships can be fundamental to constructing a society where people have close relationships Roberts et al. (2014). However, text communication services tend to develop weak bonds that help bridge online communities Ahmad, Soroya, and Mahmood (2023). Therefore, the formation of social networks and social interactions may differ between avatars and text communications.

We found these differences in social relationships between avatar and text communication applications despite each application group having different specifications, avatar appearances, and user demographics. This suggests that social relationships created on the applications are qualitatively different due to the kinds of communication, i.e., via avatars or texts. Comparison between two groups with different communication styles on the same basis enabled us this finding.

Online social support facilitates offline social resources. However, avatar communication service users who received more online social support than text communication service users tended to lack social resources. Their perceived offline social support was lower, they felt lonely, and they tended to experience bullying victimization. Thus, H3 was not supported. This may be because there are people using avatar communication services as escape places Yokotani and Takano (2021a); Lee, Lee, and Bae (2023); Hur and Baek (2024). These findings suggest that avatar users may require additional offline social resources and highlight differences in user segments and motivations for use (e.g., seeking information or alleviating loneliness). Future longitudinal studies are required for the separation of such predisposition from the effects of the application usage.

Note that X users also tend to lack offline social resources (low offline social resources and high loneliness). This may be because Japanese X users tend to think of socializing as bothersome compared with Facebook and Instagram users Watanabe (2019).

However, the association between online and offline social support was positive in the intraservice context, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies Trepte, Dienlin, and Reinecke (2015); Lin et al. (2018); Takano and Yokotani (2022). This association was stronger for avatar communication services than for text communication services. X, which tended to lack offline social resources similar to avatar communication services, did not exhibit such a strong association. Previous studies have shown that receiving online social support can enhance offline social support McKenna and Bargh (1998); Liu and Yu (2013); Thomas, Orme, and Kerrigan (2020), suggesting that avatar communication services can enhance offline social resources for those who lack offline social resources. Actually, social relationship construction via avatars in Pigg Party reduces social anxiety of sexual and gender minorities in the physical world Yokotani, Takano, Abe, and Kato (2024).

These findings were shared among three avatar communication services offering different avatar creatives, such as realistic or fancy and 3D or 2D. In other words, the fundamental effects of avatar communication were unrelated to avatar creativity, as revealed by our research findings. It will also be valuable to indicate the relationship between avatar creativity and the psychological effects on communication by comparing several types of avatars.

On the other hand, text communication applications also have advantages in online social support. Since they are asynchronous communication, people can post their self-disclosure and responses whenever they want, and it is easier for both the self-discloser and the supporter to communicate after careful consideration. For instance, on Reddit, there are subreddits where people with depression feelings can write, and their stories are heard, effectively providing online social support Choudhury and De (2014). Additionally, social media platforms like X, Facebook, and Instagram are suitable for bridging relationships Phua, Jin, and Kim (2017); Takano (2018) (weak ties Granovetter (1973)). Therefore, while avatar communities excel in providing emotional support such as empathy and respect, text media has advantages in terms of obtaining new information and perspectives. For example, individuals whose parents did not graduate from college can interact with college graduates on Facebook, gain information about universities, and improve their chances of attending college Wohn et al. (2013). These differences might generate variations in the motivations for using each application.

What can platforms do to enhance the offline resources of avatar communication service users? Improving ego networks for increasing sharing friends, that is, belonging to a densely-connected community, can increase social support Kim and Stiff (1991); Roberts et al. (2014). This is also true of online social support Takano and Yokotani (2022); Hygen et al. (2024). It seems crucial for platforms to facilitate communities in virtual worlds and help users feel that they belong to them.

Three approaches can be considered to improve ego networks: The first involves friend recommendations to increase sharing among friends. Several online communication platforms, including avatar communication services, provide potential friend recommendations Tang, Hu, and Liu (2013). The friend-of-friend algorithm, which increases the number of friends shared between users, is a major approach for friend recommendations.

The second aspect is the sharing of places of communication. The co-presence of avatar communication requires sharing of places among users. These shared places facilitate the formation of partnerships within a community Godinho et al. (2015); Bhatt and Bhatt (2020) by creating densely connected communities Takano and Nakazato (2021). Therefore, it would be effective for the platform to create a place where users wish to gather and a mechanism for them to become attached to that place.

Third, social interactions can be indirectly facilitated through avatar interventions. Avatar customization increases avatar identification Birk et al. (2016); Mancini, Imperato, and Sibilla (2018); Takano and Taka (2022) and high avatar identification enhances sociality and belonging to a community Vasalou, Joinson, and Pitt (2007); Van Reijmersdal et al. (2013); Kao and Fox Harrell (2018); Takano and Taka (2022). In particular, avatar customization, as in real life (e.g., mimicking a friend’s clothes and changing hairstyle), reinforces avatar identification Takano and Taka (2022). Users who design avatars to reflect their desired attractive selves have become sociable Messinger et al. (2008, 2019). Therefore, it would be effective for platforms to hold campaigns that facilitate avatar customization, such as in real life and making wishful avatars. For instance, the Halloween campaign can allow users to dress up their avatars and interact with online friends, similar to how they would in the physical world. This would enhance avatar identification in the virtual world and likely increase communication.

We also expect these approaches, which facilitate communication Birk et al. (2016); Birk and Mandryk (2019); Takano and Taka (2022), to improve the platforms’ key performance indicators because they enhance user engagement. In other words, the facilitation of online social support by platforms benefits not only the users but also the platforms themselves. Platforms can conduct this through as friend recommendations or seasonal campaigns, which approaches are extensions of the existing functionalities of the application. This implies that such promotion of online social support can be a seamless and acceptable approach for both platforms and their users.

Furthermore, the existence of users who used avatar communication services as escape places suggests that avatar communication services can provide psychological safety places for people lacking offline social resources. Actually, sexual and gender minorities who tend to lack offline social resources acquire social resources in Pigg Party Yokotani and Takano (2021a). Facilitating avatar communication services for those lacking offline social resources can improve their online social resources and mental health.

Finally, we summarize our theoretical contributions as follows. First, we indicated the importance of online nonverbal communications for online social support with outer validity, although previous studies Antonijevic (2008); Green-Hamann, Campbell Eichhorn, and Sherblom (2011); O’Connor et al. (2015); Takano and Tsunoda (2019); Takano and Yokotani (2022) investigated this topic in one platform. This study contributes to the psychology of nonverbal communication.

Second, the nature of online social networks may differ significantly between avatars and text communication platforms. This difference affects the quality of online social support. Online communication provides communication partners with impressions different from those in offline communication Kock (2005); Vlahovic, Roberts, and Dunbar (2012); Burke and Kraut (2016). People use these methods depending on their communication purposes and partners Burke and Kraut (2014). Consequently, qualitative differences emerged between online and offline social networks Takano (2018). This may be because, in the hierarchy of social relationships (the Dunbar circle Zhou et al. (2005); Dunbar (2018)), the level of social relationships that an individual can make depends on the means of communication. Online communication via avatars in the virtual world may have forms similar to offline communication, such as online text communication. This will contribute to social network theory and social psychology regarding friendships.

Third, we found that the relationship between online and offline social support depends on avatar or text communication. Previous studies McKenna and Bargh (1998); Liu and Yu (2013); Thomas, Orme, and Kerrigan (2020) have indicated that online social support can enhance offline social support. We demonstrated that online social support via avatars had stronger associations with offline social support than with text. This study contributes to the field of social support psychology.

Limitations and Future Works

We obtained our findings by examining and comparing three avatars and three text communication services. The mechanism of these findings must be analyzed using detailed user behavioral log data. Additionally, qualitative research, such as interviews, can provide deeper insights into online social support via avatars.

This study investigated three avatar communication applications and three text communication applications. There are many ways to communicate online, e.g., avatars in virtual reality and online bulletin boards. Recent advancements in AI technology have made it possible to create avatars that look very similar to the user and synchronize facial expressions and gestures. By conducting similar studies on these diverse communication methods and ultra-realistic avatars, such as Vasa-1, Live Portrait, or Hallo, we can better understand the scope of our findings.

The participants in this study were Japanese speakers living in Japan, which limits cultural diversity. Verifying our findings across multiple cultures would help clarify their applicability.

We studied the associations between online social support, online relational stability, and offline social resources in avatars and text communication services. An experimental study to improve online social support by manipulating social relationships, virtual communication locations, and avatar customization should be conducted to determine the intervention outcomes for ego networks.

High avatar identification enables users to enjoy games and communication in the virtual world Van Reijmersdal et al. (2013); Birk et al. (2016); Kao and Fox Harrell (2018). However, it has also been shown to increase the risk of game addiction Mancini, Imperato, and Sibilla (2018). Therefore, we have to clarify not only how to facilitate online social resources but also the relationship between this and addiction risks.

Our study builds on previous research McKenna and Bargh (1998); Lin et al. (2018); Thomas, Orme, and Kerrigan (2020) and aims to shed light on the effects of online social support on offline social support, thereby potentially deepening our understanding of this relationship. On the other hand, we can also consider that individuals with high sociality receive high levels of online and offline social support. Examining the causality of this phenomenon is also required in avatar communication.

This study deals with communication between humans through avatars. One possible approach to further enhance this is the introduction of AI-powered communication agents. For example, an AI agent could participate in human conversations to facilitate smooth dialogue and suppress aggressive remarks, thereby maintaining a psychologically safe environment and enhancing online social support between humans.

Conclusion

To understand online social support through avatars, we examined three hypotheses regarding online social support, online relational mobility, and offline social resources based on comparisons between avatars and text communication services. Our findings indicate the importance of realistic online communication experiences (nonverbal and real-time interactions with co-presence) and avatar communication service users’ problems in the physical world (lack of offline social resources). In addition, it is suggested that these problems can be resolved by enhancing online social support through avatars. This could contribute to online and offline social resource problems in future metaverse societies.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by JST, PRESTO Grant Number JPMJPR2367, Japan.

References

- Ahmad, Soroya, and Mahmood [2023] Ahmad, Z.; Soroya, S. H.; and Mahmood, K. 2023. Bridging Social Capital through the Use of Social Networking Sites: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 33(4): 473–489.

- Andalibi et al. [2016] Andalibi, N.; Haimson, O. L.; De Choudhury, M.; and Forte, A. 2016. Understanding Social Media Disclosures of Sexual Abuse Through the Lenses of Support Seeking and Anonymity. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’16, 3906–3918. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press. ISBN 9781450333627.

- Antonijevic [2008] Antonijevic, S. 2008. FROM TEXT TO GESTURE ONLINE: A Microethnographic Analysis of Nonverbal Communication in the Second Life Virtual Environment. Information, Communication & Society, 11(2): 221–238.

- Aris et al. [2023] Aris, S.; in Law, B.; Akhavan Candidate, M.; and Sabbar, S. 2023. Motivations for Consuming Avatar-Specific Virtual Items on The Zepeto Gaming Platform. Cadernos de Educação Tecnologia e Sociedade, 16(4): 1248–1258.

- Bhatt and Bhatt [2020] Bhatt, M.; and Bhatt, M. 2020. Sharing Place and Space to Promote Wellbeing for Old and Young People in a Neighbourhood. European Journal of Public Health, 30(Supplement_5).

- Birk et al. [2016] Birk, M. V.; Atkins, C.; Bowey, J. T.; and Mandryk, R. L. 2016. Fostering Intrinsic Motivation through Avatar Identification in Digital Games. In Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings, 2982–2995. Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9781450333627.

- Birk and Mandryk [2019] Birk, M. V.; and Mandryk, R. L. 2019. Improving the Efficacy of Cognitive Training for Digital Mental Health Interventions through Avatar Customization: Crowdsourced Quasi-experimental Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(1): e10133.

- Burke and Kraut [2014] Burke, M.; and Kraut, R. E. 2014. Growing Closer on Facebook: Changes in Tie Strength through Social Network Site Use. In Proceedings of the 32nd annual ACM conference on Human factors in computing systems (CHI ’14), 4187–4196. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press. ISBN 9781450324731.

- Burke and Kraut [2016] Burke, M.; and Kraut, R. E. 2016. The Relationship Between Facebook Use and Well-Being Depends on Communication Type and Tie Strength. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 21(4): 265–281.

- Choudhury and De [2014] Choudhury, M., De; and De, S. 2014. Mental Health Discourse on reddit: Self-Disclosure, Social Support, and Anonymity. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

- Chung [2013] Chung, J. E. 2013. Social Interaction in Online Support Groups: Preference for Online Social Interaction over Offline Social Interaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4): 1408–1414.

- Cohen and Wills [1985] Cohen, S.; and Wills, T. A. 1985. Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2): 310–357.

- Cole et al. [2017] Cole, D. A.; Nick, E. A.; Zelkowitz, R. L.; Roeder, K. M.; and Spinelli, T. 2017. Online Social Support for Young People: Does It Recapitulate in-person Social Support; Can It Help? Computers in Human Behavior, 68: 456–464.

- Declercq et al. [2007] Declercq, F.; Vanheule, S.; Markey, S.; and Willemsen, J. 2007. Posttraumatic Distress in Security Guards and the Various Effects of Social Support. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(12): 1239–1246.

- Dunbar [2018] Dunbar, R. 2018. The Anatomy of Friendship. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(1): 32–51.

- Fukuoka and Hashimoto [1997] Fukuoka, Y.; and Hashimoto, T. 1997. Stress-buffering Effects of Perceived Social Supports from Family Members and Friends: A Comparison of College Students and Middle-aged Adults. The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 68(5): 403–409.

- Godinho et al. [2015] Godinho, S. C.; Woolley, M.; Webb, J.; and Winkel, K. D. 2015. Sharing Place, Learning Together: Perspectives and Reflections on an Educational Partnership Formation With a Remote Indigenous Community School. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 44(1): 11–25.

- Granovetter [1973] Granovetter, M. 1973. The Strength Of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78: 1360–1380.

- Green-Hamann, Campbell Eichhorn, and Sherblom [2011] Green-Hamann, S.; Campbell Eichhorn, K.; and Sherblom, J. C. 2011. An Exploration of Why People Participate in Second Life Social Support Groups. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 16(4): 465–491.

- Greiner, Caravella, and Roth [2014] Greiner, B.; Caravella, M.; and Roth, A. E. 2014. Is Avatar-to-Avatar Communication as Effective as Face-to-Face Communication? An Ultimatum Game experiment in First and Second Life. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 108: 374–382.

- Hughes et al. [2004] Hughes, M. E.; Waite, L. J.; Hawkley, L. C.; and Cacioppo, J. T. 2004. A Short Scale for Measuring Loneliness in Large Surveys. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0164027504268574, 26(6): 655–672.

- Hur and Baek [2024] Hur, H. J.; and Baek, E. 2024. Understanding Metaverse Consumers Through Escapism Motives: Focusing on Roblox and Zepeto. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 1–13.

- Hygen et al. [2024] Hygen, B. W.; Wendelborg, C.; Solstad, B. E.; Stenseng, F.; Øverland, M. B.; and Skalicka, V. 2024. Gaming Motivation and Well-being among Norwegian Adult Gamers: the Role of Gender and Disability. Frontiers in Medical Technology, 6: 1330926.

- Igarashi [2019] Igarashi, T. 2019. Development of the Japanese Version of the Three-item Loneliness Scale. BMC Psychology, 7(1): 1–8.

- Jaidka, Guntuku, and Ungar [2018] Jaidka, K.; Guntuku, S. C.; and Ungar, L. H. 2018. Facebook versus Twitter: Differences in Self-Disclosure and Trait Prediction. undefined.

- Kang, Dabbish, and Sutton [2016] Kang, R.; Dabbish, L. A.; and Sutton, K. 2016. Strangers on Your Phone: Why People Use Anonymous Communication Applications. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing - CSCW ’16, 358–369. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press. ISBN 9781450335928.

- Kao and Fox Harrell [2018] Kao, D.; and Fox Harrell, D. 2018. The Effects of Badges and Avatar Identification on Play and Making in Educational Games. In Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings, volume 2018-April, 1–19. New York, New York, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9781450356206.

- Kendrick, Jutengren, and Stattin [2012] Kendrick, K.; Jutengren, G.; and Stattin, H. 2012. The Protective Role of Supportive Friends against Bullying Perpetration and Victimization. Journal of Adolescence, 35(4): 1069–1080.

- Kim and Stiff [1991] Kim, H. J.; and Stiff, J. B. 1991. Social Networks and the Development of Close Relationships. Human Communication Research, 18(1): 70–91.

- Ko and Kim [2024] Ko, C.; and Kim, S. 2024. Adolescent Female Users’ Avatar Creation in Social Virtual Worlds: Opportunities and Challenges. Behavioral Sciences 2024, Vol. 14, Page 539, 14(7): 539.

- Kock [2005] Kock, N. 2005. Media Richness or Media Naturalness? The Evolution of Our Biological Communication Apparatus and Its Influence on Our Behavior toward E-communication Tools. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 48(2): 117–130.

- Küster, Krumhuber, and Kappas [2015] Küster, D.; Krumhuber, E.; and Kappas, A. 2015. Nonverbal Behavior Online: A Focus on Interactions with and via Artificial Agents and Avatars. In The Social Psychology of Nonverbal Communication, 272–302. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Ledbetter and Larson [2008] Ledbetter, A. M.; and Larson, K. A. 2008. Nonverbal Cues in E-mail Supportive Communication. Information, Communication & Society, 11(8): 1089–1110.

- Lee, Lee, and Bae [2023] Lee, E. J.; Lee, W.; and Bae, I. 2023. What Is the Draw of the Metaverse? Personality Correlates of Zepeto Use Motives and Their Associations With Psychological Well-Being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 26(3): 161–168.

- Lee et al. [2024] Lee, E.-J.; Park, S.; Lee, W.; and Kim, H. S. 2024. Identity Experiment in the Metaverse: Making Sense of Zepeto Users’ Avatar Use. International Journal of Communication, 18(0): 22.

- Lin et al. [2018] Lin, M. P.; Wu, J. Y. W.; You, J.; Chang, K. M.; Hu, W. H.; and Xu, S. 2018. Association between Online and Offline Social Support and Internet Addiction in a Representative Sample of Senior High School Students in Taiwan: The Mediating Role of Self-esteem. Computers in Human Behavior, 84: 1–7.

- Liu and Yu [2013] Liu, C.-Y.; and Yu, C.-P. 2013. Can Facebook Use Induce Well-Being? Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(9): 674–678.

- Liu, Wright, and Hu [2018] Liu, D.; Wright, K. B.; and Hu, B. 2018. A meta-analysis of Social Network Site use and social support. Computers and Education, 127: 201–213.

- Malecki and Demaray [2003] Malecki, C. K.; and Demaray, M. K. 2003. What Type of Support do they Need? Investigating Student Adjustment as Related to Emotional, Informational, Appraisal, and Instrumental Support. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(3): 231–252.

- Mancini, Imperato, and Sibilla [2018] Mancini, T.; Imperato, C.; and Sibilla, F. 2018. Does Avatar’s Character and Emotional Bond Expose to Gaming Addiction? Two Studies on Virtual Self-discrepancy, Avatar Identification and Gaming Addiction in Massively Multiplayer Online Role-playing Game Players. Computers in Human Behavior.

- Manusov and Patterson [2006] Manusov, V. L.; and Patterson, M. L. 2006. The SAGE handbook of nonverbal communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781412904049.

- McCloskey et al. [2015] McCloskey, W.; Iwanicki, S.; Lauterbach, D.; Giammittorio, D. M.; and Maxwell, K. 2015. Are Facebook “Friends” Helpful? Development of a Facebook-Based Measure of Social Support and Examination of Relationships Among Depression, Quality of Life, and Social Support. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(9): 499–505.

- McKenna and Bargh [1998] McKenna, K. Y. A.; and Bargh, J. A. 1998. Coming out in the Age of the Internet: Identity “Demarginalization” through Virtual Group Participation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3): 681–694.

- Mehrabian [1970] Mehrabian, A. 1970. Nonverbal Communication. Chicago: Aldine-Atherton.

- Mesch and Talmud [2006] Mesch, G.; and Talmud, I. 2006. Online Friendship Formation, Communication Channels, and Social Closeness. International Journal of Internet Science, 1(1): 29–44.

- Messinger et al. [2019] Messinger, P. R.; Ge, X.; Smirnov, K.; Stroulia, E.; and Lyons, K. 2019. Reflections of the Extended Self: Visual Self-representation in Avatar-mediated Environments. Journal of Business Research, 100: 531–546.

- Messinger et al. [2008] Messinger, P. R.; Ge, X.; Stroulia, E.; Lyons, K.; Smirnov, K.; and Bone, M. 2008. On the Relationship between My Avatar and Myself. Journal of Virtual Worlds Research, 1(2): 1–17.

- Mitra and Golz [2016] Mitra, B. M.; and Golz, P. 2016. Exploring Intrinsic Gender Identity Using Second Life. Journal For Virtual Worlds Research, 9(2).

- Obst et al. [2019] Obst, P.; Shakespeare-Finch, J.; Krosch, D. J.; and Rogers, E. J. 2019. Reliability and Validity of the Brief 2-Way Social Support Scale: An Investigation of Social Support in Promoting Older Adult Well-being. SAGE open medicine, 7: 2050312119836020.

- O’Connor et al. [2015] O’Connor, E. L.; Longman, H.; White, K. M.; and Obst, P. L. 2015. Sense of Community, Social Identity and Social Support Among Players of Massively Multiplayer Online Games (MMOGs): A Qualitative Analysis. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 25(6): 459–473.

- Oh et al. [2023] Oh, H. J.; Kim, J.; Chang, J. J.; Park, N.; and Lee, S. 2023. Social Benefits of Living in the Metaverse: The Relationships among Social Presence, Supportive Interaction, Social Self-efficacy, and Feelings of Loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior, 139: 107498.

- Olweus [1996] Olweus, D. 1996. The Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Bergen, Norway: University of Bergen, Research Center for Health Promotion (HEMIL Center).

- Oriol et al. [2017] Oriol, X.; Torres, J.; Miranda, R.; Bilbao, M.; and Ortúzar, H. 2017. Comparing Family, Friends and Satisfaction with School Experience as Predictors of SWB in Children Who Have and Have not Made the Transition to Middle School in Different Countries. Children and Youth Services Review, 80: 149–156.

- Pérez-Aldana et al. [2021] Pérez-Aldana, C. A.; Lewinski, A. A.; Johnson, C. M.; Vorderstrasse, A. A.; and Myneni, S. 2021. Exchanges in a Virtual Environment for Diabetes Self-management Education and Support: Social Network Analysis. JMIR Diabetes, 6(1): e21611.

- Phua, Jin, and Kim [2017] Phua, J.; Jin, S. V.; and Kim, J. J. 2017. Uses and Gratifications of Social Networking Sites for Bridging and Bonding Social Capital: A Comparison of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat. Computers in Human Behavior, 72: 115–122.

- Pierce et al. [2020] Pierce, M.; Hope, H.; Ford, T.; Hatch, S.; Hotopf, M.; John, A.; Kontopantelis, E.; Webb, R.; Wessely, S.; McManus, S.; and Abel, K. M. 2020. Mental Health before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Longitudinal Probability Sample Survey of the UK Population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(10): 883–892.

- Reblin et al. [2018] Reblin, M.; Ketcher, D.; Forsyth, P.; Mendivil, E.; Kane, L.; Pok, J.; Meyer, M.; Wu, Y. P.; and Agutter, J. 2018. Outcomes of an Electronic Social Network Intervention with Neuro-oncology Patient Family Caregivers. Journal of Neuro-Oncology, 139(3): 643–649.

- Roberts et al. [2014] Roberts, S.; Arrow, H.; Gowlett, J.; Lehmann, J.; and Dunbar, R. 2014. Close Social Relationships: An Evolutionary Perspective. Oxford University Press.

- Rothon et al. [2011] Rothon, C.; Head, J.; Klineberg, E.; and Stansfeld, S. 2011. Can Social Support Protect Bullied Adolescents from Adverse Outcomes? A Prospective Study on the Effects of Bullying on the Educational Achievement and Mental Health of Adolescents at Secondary Schools in East London. Journal of Adolescence, 34(3): 579–588.

- Semmer et al. [2008] Semmer, N. K.; Elfering, A.; Jacobshagen, N.; Perrot, T.; Beehr, T. A.; and Boos, N. 2008. The Emotional Meaning of Instrumental Social Support. International Journal of Stress Management, 15(3): 235–251.

- Shakespeare-Finch and Obst [2011] Shakespeare-Finch, J.; and Obst, P. L. 2011. The Development of the 2-way Social Support Scale: A Measure of Giving and Receiving Emotional and Instrumental Support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(5): 483–490.

- Sharma and De Choudhury [2018] Sharma, E.; and De Choudhury, M. 2018. Mental Health Support and its Relationship to Linguistic Accommodation in Online Communities. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’18, 1–13. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press.

- Takano [2018] Takano, M. 2018. Two Types of Social Grooming Methods Depending on the Trade-off between the Number and Strength of Social Relationships. Royal Society Open Science, 5(8): 180148.

- Takano and Nakazato [2021] Takano, M.; and Nakazato, K. 2021. Difference in Communication Systems Explained by Balance between Edge and Node Activations. JPhys Complexity, 2(2): 15.

- Takano and Taka [2022] Takano, M.; and Taka, F. 2022. Fancy Avatar Identification and Behaviors in the Virtual World: Preceding Avatar Customization and Succeeding Communication. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 6: 100176.

- Takano and Tsunoda [2019] Takano, M.; and Tsunoda, T. 2019. Self-Disclosure of Bullying Experiences and Social Support in Avatar Communication: Analysis of Verbal and Nonverbal Communications. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 13(01): 473–481.

- Takano and Yokotani [2022] Takano, M.; and Yokotani, K. 2022. Online Social Support via Avatar Communication Buffers Harmful Effects of Offline Bullying Victimization. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 16: 980–992.

- Tang, Hu, and Liu [2013] Tang, J.; Hu, X.; and Liu, H. 2013. Social recommendation: a review. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 3(4): 1113–1133.

- Thomas, Orme, and Kerrigan [2020] Thomas, L.; Orme, E.; and Kerrigan, F. 2020. Student Loneliness: The Role of Social Media Through Life Transitions. Computers & Education, 146: 103754.

- Trepte, Dienlin, and Reinecke [2015] Trepte, S.; Dienlin, T.; and Reinecke, L. 2015. Influence of Social Support Received in Online and Offline Contexts on Satisfaction With Social Support and Satisfaction With Life: A Longitudinal Study. Media Psychology, 18(1): 74–105.

- Tsuboi, Hirai, and Kondo [2016] Tsuboi, H.; Hirai, H.; and Kondo, K. 2016. Giving Social Support to Outside Family May be a Desirable Buffer against Depressive Symptoms in Community-dwelling Older Adults: Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study. BioPsychoSocial Medicine, 10(1): 1–11.

- van der Land et al. [2011] van der Land, S.; Schouten, A. P.; van den Hooff, B.; and Feldberg, F. 2011. Modeling the Metaverse: A Theoretical Model of Effective Team Collaboration in 3D Virtual Environments. Journal of Virtual Worlds Research, 4(3): 1–16.

- Van Reijmersdal et al. [2013] Van Reijmersdal, E. A.; Jansz, J.; Peters, O.; and Van Noort, G. 2013. Why Girls Go Pink: Game Character Identification and Game-players’ Motivations. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6): 2640–2649.

- Vasalou, Joinson, and Pitt [2007] Vasalou, A.; Joinson, A. N.; and Pitt, J. 2007. Constructing my Online Self: Avatars that Increase Self-focused Attention. In Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings, 445–448. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press. ISBN 1595935932.

- Vlahovic, Roberts, and Dunbar [2012] Vlahovic, T. A.; Roberts, S.; and Dunbar, R. 2012. Effects of Duration and Laughter on Subjective Happiness within Different Modes of Communication. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 17(4): 436–450.

- Watanabe [2019] Watanabe, Y. 2019. Young People Use Social Media for Gathering Information. The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcast Research, 69(5): 38–56.

- Westmyer and Myers [2009] Westmyer, S. A.; and Myers, S. A. 2009. Communication Skills and Social Support Messages Across Friendship Levels. Communication Research Reports, 13(2): 191–197.

- Wills and Shinar [2015] Wills, T. A.; and Shinar, O. 2015. Measuring Perceived and Received Social Support. In Social Support Measurement and Intervention, 86–135. Oxford University Press.

- Wohn et al. [2013] Wohn, D. Y.; Ellison, N. B.; Khan, M. L.; Fewins-Bliss, R.; and Gray, R. 2013. The role of social media in shaping first-generation high school students’ college aspirations: A social capital lens. Computers & Education, 63: 424–436.

- Yokotani and Takano [2021a] Yokotani, K.; and Takano, M. 2021a. Differences in Victim Experiences by Gender/Sexual Minority Statuses in Japanese Virtual Communities. Journal of Community Psychology, 49: 1598–1616.

- Yokotani and Takano [2021b] Yokotani, K.; and Takano, M. 2021b. Predicting Cyber Offenders and Victims and Their Offense and Damage Time from Routine Chat Times and Online Social Network Activities. Computers in Human Behavior, 107099.

- Yokotani and Takano [2022] Yokotani, K.; and Takano, M. 2022. Avatars’ Social Rhythms in Online Games Indicate Their Players’ Depression. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking.

- Yokotani, Takano, and Abe [2024] Yokotani, K.; Takano, M.; and Abe, N. 2024. Can Likes Returned by Peers within a Day Improve Users’ Depressive/Manic Levels in a Massive Multiplayer Online Game? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Computational Social Science, 1–25.

- Yuan et al. [2025] Yuan, J.; Peng, X.; Liu, Y.; and Wang, Q. 2025. “Don’t Look at Me!”: The Role of Avatars’ Presentation Style and Gaze Direction in Social Chatbot Design. Computers in Human Behavior, 164: 108501.

- Yuki et al. [2007] Yuki, M.; Schug, J.; Horikawa, H.; Takemura, K.; Sato, K.; Yokota, K.; and Kamaya, K. 2007. Development of a Scale to Measure Perceptions of Relational Mobility in Society.

- Zhou et al. [2005] Zhou, W.-X.; Sornette, D.; Hill, R. A.; and Dunbar, R. I. 2005. Discrete Hierarchical Organization of Social Group Sizes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272(1561): 439–444.

- Yokotani, Takano, Abe, and Kato [2024] Yokotani, K.; Takano, M.; Abe, N.; Kato, T. 2024. Improving Social Anxiety in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Questioning, Intersex, and Asexual Individuals through Avatar Customization and Communication. Asian Journal of Social Psychology.

Appendixes

| Avatar | Text | Coef. | Std. Err. | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Life | 0.5761 | 0.0487 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | 0.9572 | 0.0502 | 0.001 | *** | |

| 0.8967 | 0.0508 | 0.001 | *** | ||

| ZEPETO | 0.4910 | 0.0486 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | 0.8721 | 0.0499 | 0.001 | *** | |

| 0.8116 | 0.0503 | 0.001 | *** | ||

| Pigg Party | 0.3749 | 0.0484 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | 0.7560 | 0.0497 | 0.001 | *** | |

| 0.6955 | 0.0501 | 0.001 | *** |

| Avatar | Text | Coef. | Std. Err. | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Life | -0.3545 | 0.0440 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | -0.1380 | 0.0454 | 0.0285 | * | |

| -0.1806 | 0.0459 | 0.0012 | ** | ||

| ZEPETO | -0.4098 | 0.0439 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | -0.1934 | 0.0451 | 0.001 | *** | |

| -0.2360 | 0.0454 | 0.001 | *** | ||

| Pigg Party | -0.3456 | 0.0437 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | -0.1291 | 0.0449 | 0.0467 | * | |

| -0.1717 | 0.0453 | 0.0021 | ** |

| Avatar | Text | Coef. | Std. Err. | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Life | -0.3827 | 0.0517 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | -0.2754 | 0.0534 | 0.001 | *** | |

| -0.3996 | 0.0540 | 0.001 | *** | ||

| ZEPETO | -0.3860 | 0.0516 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | -0.2787 | 0.0530 | 0.001 | *** | |

| -0.4029 | 0.0535 | 0.001 | *** | ||

| Pigg Party | -0.4111 | 0.0514 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | -0.3038 | 0.0529 | 0.001 | *** | |

| -0.4280 | 0.0532 | 0.001 | *** |

| Avatar | Text | Coef. | Std. Err. | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Life | -0.2289 | 0.0517 | 0.0001 | *** | |

| X | -0.0144 | -0.0533 | 0.9998 | ||

| -0.2430 | 0.0539 | 0.001 | *** | ||

| ZEPETO | -0.2541 | 0.0515 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | -0.0109 | 0.0530 | 0.9999 | ||

| -0.2683 | 0.0534 | 0.001 | *** | ||

| Pigg Party | -0.2339 | 0.0513 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | -0.0093 | -0.0528 | 1.0000 | ||

| -0.2481 | 0.0532 | 0.001 | *** |

| Avatar | Text | Coef. | Std. Err. | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Life | 0.1006 | 0.0177 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | 0.0189 | 0.0183 | 0.9071 | ||

| 0.0657 | 0.0185 | 0.0050 | ** | ||

| ZEPETO | 0.1001 | 0.0177 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | 0.0184 | 0.0182 | 0.9131 | ||

| 0.0652 | 0.0183 | 0.0048 | ** | ||

| Pigg Party | 0.1241 | 0.0176 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | 0.0424 | 0.0181 | 0.1770 | ||

| 0.0892 | 0.0182 | 0.001 | *** |

| Avatar | Text | Coef. | Std. Err. | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Life | 0.8123 | 0.0298 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | 0.9191 | 0.0307 | 0.001 | *** | |

| 0.8920 | 0.0311 | 0.001 | *** | ||

| ZEPETO | 0.7407 | 0.0297 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | 0.8476 | 0.0305 | 0.001 | *** | |

| 0.8204 | 0.0308 | 0.001 | *** | ||

| Pigg Party | 0.6726 | 0.0296 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | 0.7794 | 0.0304 | 0.001 | *** | |

| 0.7523 | 0.0306 | 0.001 | *** |

| Avatar | Text | Diff. | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Life | 0.5093 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | 0.5108 | 0.001 | *** | |

| 0.5734 | 0.001 | *** | ||

| ZEPETO | 0.3822 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | 0.3838 | 0.001 | *** | |

| 0.4464 | 0.001 | *** | ||

| Pigg Party | 0.4164 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | 0.4179 | 0.001 | *** | |

| 0.4805 | 0.001 | *** |

| Avatar | Text | Diff. | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Life | 0.3475 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | 0.3462 | 0.001 | *** | |

| 0.4560 | 0.001 | *** | ||

| ZEPETO | 0.2469 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | 0.2456 | 0.001 | *** | |

| 0.3554 | 0.001 | *** | ||

| Pigg Party | 0.2923 | 0.001 | *** | |

| X | 0.2910 | 0.001 | *** | |

| 0.4009 | 0.001 | *** |