junginger@uvic.ca

Comment on “Strong Meissner screening change in superconducting radio frequency cavities due to mild baking” [Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 072601 (2014)]

In a recent Letter by Romanenko et al. [1], the authors used low-energy muon spin rotation (LE-SR) [2, 3] to measure the Meissner screening profile in cutouts from \chNb superconducting radio frequency (SRF) cavities, systematically comparing how different surface treatments affect the screening properties of the elemental type-II superconductor. They reported a “strong” modification to the character of the screening profile upon mild baking at for [4], which was interpreted as a depth-dependent carrier mean-free-path resulting from a “gradient in vacancy concentration” near the surface [1]. While this observation led to speculation that this surface treatment yields an “effective” superconducting bilayer (see e.g., [5]), we suggest that its likeness to such [6] is accidental and that the behavior is an artifact from the analysis.

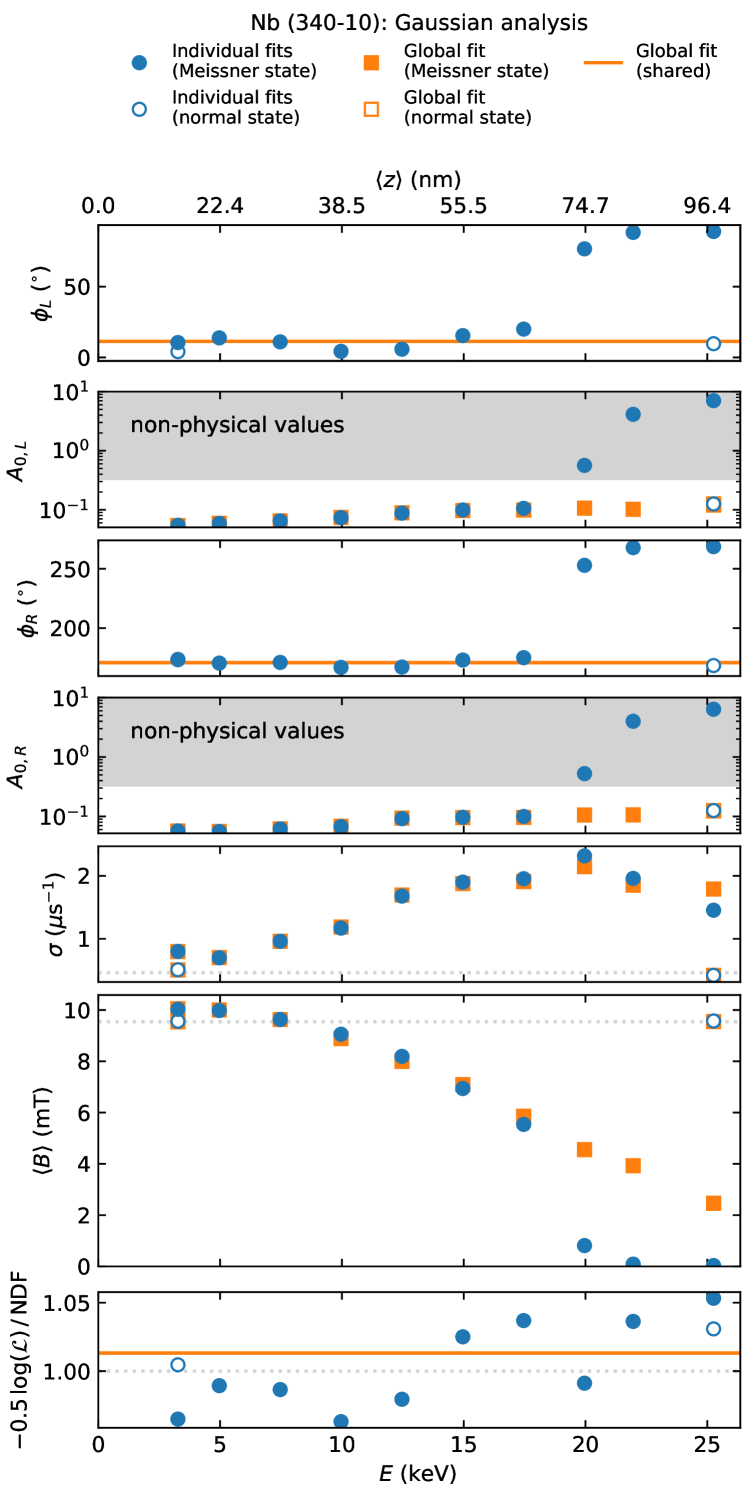

Issues with the reported analysis are apparent upon scrupulous inspection of Figures 3 and 4 in the Letter [1], where the mean field below the sample surface (obtained through different analysis models) is plotted against the mean muon stopping depth . In Figure 3, where was determined from fits to a Gaussian model (i.e., a Gaussian-damped cosine function), 111We also note that the assignment of the plotted symbols (, , and ) in Figure 3’s caption [1] are inconsistent with the legend in the inset. Additionally, in both Figures 3 and 4 [1], several points appear at , but without explanation. Clearly, these cannot originate from an actual measurement by LE-SR where “muon implantation energies of were used”. Romanenko et al. [1] correctly draw attention to the strikingly different dependence found upon mild baking [4]; however, no mention is made as to why the data deviate from exponential decay (i.e., the well-known form of Meissner screening profiles for thick slabs [8]) for all surface treatments. Instead, the discussion shifts to accounting for non-local electrodynamics [9, 10] and strong electron-phonon coupling [11] in the formulation of . While the former can cause to decay non-exponentially, its effect is known to be subtle for \chNb [12], and it’s unclear how such corrections could account for the abrupt discontinuity observed at .

This “step” in vs. persists in Figure 4 [1], where was determined from fits to Pippard’s non-local model [9, 12], including results from treating the LE-SR data individually or as part of a global analysis. Surprisingly, the dependence of the other two cutouts (100-6 and 30-6) appear drastically different from Figure 3, with their field attenuation now resembling an exponential. While this might suggest that the Gaussian analysis is too crude an approach, such a conclusion is inconsistent with earlier LE-SR measurements on a \chNb thin film [12]. The persistence of the baked sample’s sudden drop in is both conspicuous and non-physical, especially considering that it implies an unrealistically large current density (where is the permeability constant) at the depth of the discontinuity (see e.g., [5, 13]).

Motivated by results from our own investigation into how SRF cavity treatments affect Meissner screening in \chNb (which showed exponential screening profiles for all treatments studied) [14], we revisited the original LE-SR data reported in the Letter [1]. In general, we find that the “step” near is only reproduced when fits adopt parameters with non-physical values. For example, following the Gaussian analysis described in the Letter [1], we obtain the fit parameters shown in Figure˜1, illustrating that the sudden drop in is coincident with a divergence in both the phase and initial asymmetry , neither of which is realistic 222The phase of the spin-precession signal is determined by the beam properties and should be unchanged across a series of related measurements (e.g., at different implantation energies). Similarly, the initial asymmetry is determined by the properties of decay and the detector setup, with values rarely exceeding (i.e., the value obtained following averaging over all decay positron energies).. This situation is easily rectified by constraining the fit (e.g., through treating the phase as a shared parameter), upon which the “step” vanishes without any meaningful penalty to the overall goodness-of-fit.

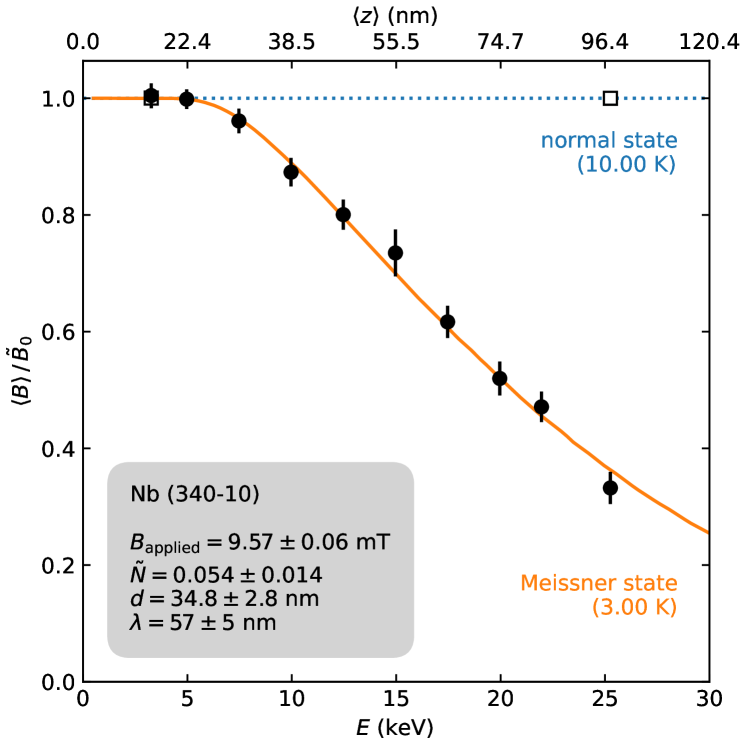

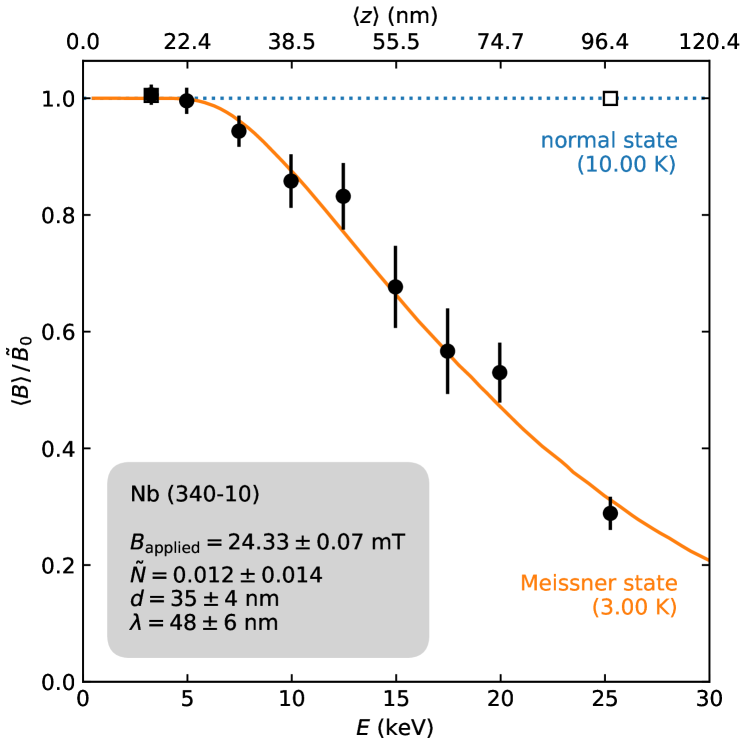

To provide a refined assessment of the Meissner screening in the 340-10 cavity cutout, we also re-analyzed the LE-SR data using the approach described in Ref. 14, wherein a skewed Gaussian is used to approximate the local field distribution along with an improved simulation of stopping in \chNb. 333At this juncture, we emphasize that there is no “intrinsic” flaw in the analysis approaches described in the Letter [1] and that both should work well when applied diligently. In fact, the workflow outlined in Ref. 14 can be considered as further refinement to the methodology used to characterize \chNb SRF materials using LE-SR. Screening profiles determined from this procedure are shown in Figure˜2, where any discontinuity in is notably absent. Moreover, we find that the profiles are well-described by an exponential , as expected for a “dirty” superconductor [8] and consistent with our other results [14]. Note that we also included an effective demagnetization factor in this analysis, which accounts for the (geometric) enhancement of the applied field well-into the Meissner state. 444That is, for certain combinations of material geometries and field directions (e.g., a thick slab with the field applied parallel to its surface), the expelled magnetic flux that closely contours the sample’s dimensions can be “squeezed” along certain areas of the material’s surface, leading to the appearance that the applied field has been enhanced (see e.g., Ref. 19). The manifestation of this phenomenon is evident in Figure 1, where at low the in the Meissner state exceeds that in the normal state. We stress that incorporating this detail was necessary to correctly describe the data. 555The omission of this detail in the Letter [1] is likely because of it’s seldom use in the literature. For example, most LE-SR experiments at the time focussed on thin film samples, whose dimensions ensure that .

Lastly, we note that our re-analysis also finds an unusually large non-superconducting “dead layer” at the surface of the 340-10 cutout. This is easily identified by ’s asymptotic approach to the “effective” applied field with decreasing implantation energy (i.e., ). We find that (see Figure˜2), which is significantly larger than the implied in the Letter [1], as well as those given in other reports [14, 12]. While is a sample-dependent (rather than an intrinsic material-dependent) property, this value is exceptionally large and is unlikely a result of surface roughness alone (see e.g., [20, 21]). An intriguing alterative (in line with the ideas presented by Romanenko et al. [1]) is that there may be a near-surface region where the magnetic penetration depth is spatially inhomogeneous. This idea has been considered theoretically on general grounds [22] and more recently in the context of SRF cavities [23, 24]. The impact of such an effect, however, is likely subtle and beyond the resolution of the current measurements.

In summary, we re-analyzed the LE-SR data originally reported in the Letter by Romanenko et al. [1], revealing the absence of any “strong” changes to the Meissner screening profile of \chNb upon mild baking [4], with the field screening well-described by an exponential London model [8]. Interestingly, the re-analysis also uncovered an unusually large “dead layer”, which may suggest the presence of spatial inhomogeneities in the screening properties close to the surface (e.g., from a depth-dependent penetration depth) [22, 23, 24]. The data suggests that their effect on is likely subtle, necessitating high-resolution measurements probing the near-surface region () to be conclusive. We hope that this Comment will stimulate further investigation into the matter.

Acknowledgements.

We thank E. R. Lechner for useful discussions. This work was supported by an NSERC Award to T. Junginger.Author Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Author Contributions

Ryan M. L. McFadden: Conceptualization (equal); Formal Analysis (lead); Software (lead); Writing - Original Draft Preparation (lead); Writing - Review & Editing (equal). Md Asaduzzaman: Formal Analysis (supporting); Software (supporting); Writing - Review & Editing (supporting). Tobias Junginger: Conceptualization (equal); Funding Acquisition (lead); Writing - Review & Editing (equal).

Data Availability

Raw data from LE-SR experiments of Romanenko et al. [1] were generated at the Swiss Muon Source SS, Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, Switzerland. Individual data files are available for download from: http://musruser.psi.ch/. Derived data supporting the findings of this Comment are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

- Romanenko et al. [2014] A. Romanenko, A. Grassellino, F. Barkov, A. Suter, Z. Salman, and T. Prokscha, “Strong Meissner screening change in superconducting radio frequency cavities due to mild baking,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 072601 (2014).

- Bakule and Morenzoni [2004] P. Bakule and E. Morenzoni, “Generation and applications of slow polarized muons,” Contemp. Phys. 45, 203–225 (2004).

- Morenzoni et al. [2004] E. Morenzoni, T. Prokscha, A. Suter, H. Luetkens, and R. Khasanov, “Nano-scale thin film investigations with slow polarized muons,” J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 16, S4583–S4601 (2004).

- Ciovati [2004] G. Ciovati, “Effect of low-temperature baking on the radio-frequency properties of niobium superconducting cavities for particle accelerators,” J. Appl. Phys. 96, 1591–1600 (2004).

- Kubo [2017] T. Kubo, “Multilayer coating for higher accelerating fields in superconducting radio-frequency cavities: a review of theoretical aspects,” Supercond. Sci. Technol. 30, 023001 (2017).

- [6] M. Asaduzzaman, R. M. L. McFadden, A.-M. Valente-Feliciano, D. R. Beverstock, A. Suter, Z. Salman, T. Prokscha, and T. Junginger, “Evidence for current suppression in superconductor-superconductor bilayers,” arXiv:2304.09360 [cond-mat.supr-con] .

- Note [1] We also note that the assignment of the plotted symbols (, , and ) in Figure 3’s caption [1] are inconsistent with the legend in the inset. Additionally, in both Figures 3 and 4 [1], several points appear at , but without explanation. Clearly, these cannot originate from an actual measurement by LE-SR where “muon implantation energies of were used”.

- Tinkham [1996] M. Tinkham, Introduction to Superconductivity, 2nd ed., International Series in Pure and Applied Physics (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1996).

- Pippard [1953] A. B. Pippard, “An experimental and theoretical study of the relation between magnetic field and current in a superconductor,” Proc. R. Soc. London A 216, 547––568 (1953).

- Bardeen, Cooper, and Schrieffer [1957] J. Bardeen, L. N. Cooper, and J. R. Schrieffer, “Theory of superconductivity,” Phys. Rev. 108, 1175–1204 (1957).

- Nam [1967] S. B. Nam, “Theory of electromagnetic properties of superconducting and normal systems. I,” Phys. Rev. 156, 470–486 (1967).

- Suter et al. [2005] A. Suter, E. Morenzoni, N. Garifianov, R. Khasanov, E. Kirk, H. Luetkens, T. Prokscha, and M. Horisberger, “Observation of nonexponential magnetic penetration profiles in the Meissner state: A manifestation of nonlocal effects in superconductors,” Phys. Rev. B 72, 024506 (2005).

- Checchin and Grassellino [2020] M. Checchin and A. Grassellino, “High-field Q-slope mitigation due to impurity profile in superconducting radio-frequency cavities,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 032601 (2020).

- McFadden et al. [2023] R. M. L. McFadden, M. Asaduzzaman, T. Prokscha, Z. Salman, A. Suter, and T. Junginger, “Depth-resolved measurements of the Meissner screening profile in surface-treated \chNb,” Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 044018 (2023).

- Note [2] The phase of the spin-precession signal is determined by the beam properties and should be unchanged across a series of related measurements (e.g., at different implantation energies). Similarly, the initial asymmetry is determined by the properties of decay and the detector setup, with values rarely exceeding (i.e., the value obtained following averaging over all decay positron energies).

- Note [3] At this juncture, we emphasize that there is no “intrinsic” flaw in the analysis approaches described in the Letter [1] and that both should work well when applied diligently. In fact, the workflow outlined in Ref. 14 can be considered as further refinement to the methodology used to characterize \chNb SRF materials using LE-SR.

- Note [4] That is, for certain combinations of material geometries and field directions (e.g., a thick slab with the field applied parallel to its surface), the expelled magnetic flux that closely contours the sample’s dimensions can be “squeezed” along certain areas of the material’s surface, leading to the appearance that the applied field has been enhanced (see e.g., Ref. 19). The manifestation of this phenomenon is evident in Figure˜1, where at low the in the Meissner state exceeds that in the normal state.

- Note [5] The omission of this detail in the Letter [1] is likely because of it’s seldom use in the literature. For example, most LE-SR experiments at the time focussed on thin film samples, whose dimensions ensure that .

- Brandt [2000] E. H. Brandt, “Superconductors in realistic geometries: geometric edge barrier versus pinning,” Physica C 332, 99–107 (2000).

- Lindstrom, Wetton, and Kiefl [2014] M. Lindstrom, B. Wetton, and R. Kiefl, “Mathematical modelling of the effect of surface roughness on magnetic field profiles in type II superconductors,” J. Eng. Math. 85, 149–177 (2014).

- Lindstrom, Fang, and Kiefl [2016] M. Lindstrom, A. C. Y. Fang, and R. F. Kiefl, “Effect of surface roughness on the magnetic field profile in the meissner state of a superconductor,” J. Supercond. Novel Magn. 29, 1499–1507 (2016).

- Barash [2014] Y. S. Barash, “The magnetic penetration depth influenced by the proximity to the surface,” J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 26, 045702 (2014).

- Ngampruetikorn and Sauls [2019] V. Ngampruetikorn and J. A. Sauls, “Effect of inhomogeneous surface disorder on the superheating field of superconducting RF cavities,” Phys. Rev. Res. 1, 012015(R) (2019).

- Lechner et al. [2021] E. M. Lechner, J. W. Angle, F. A. Stevie, M. J. Kelley, C. E. Reece, and A. D. Palczewski, “RF surface resistance tuning of superconducting niobium via thermal diffusion of native oxide,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 119, 082601 (2021).