Continuity of the Effective Path Delay Operator for Networks Based on the Link Delay Model

Abstract

This paper is concerned with a dynamic traffic network performance model, known as dynamic network loading (DNL), that is frequently employed in the modeling and computation of analytical dynamic user equilibrium (DUE). As a key component of continuous-time DUE models, DNL aims at describing and predicting the spatial-temporal evolution of traffic flows on a network that is consistent with established route and departure time choices of travelers, by introducing appropriate dynamics to flow propagation, flow conservation, and travel delays. The DNL procedure gives rise to the path delay operator, which associates a vector of path flows (path departure rates) with the corresponding path travel costs. In this paper, we establish strong continuity of the path delay operator for networks whose arc flows are described by the link delay model (Friesz et al.,, 1993). Unlike result established in Zhu and Marcotte, (2000), our continuity proof is constructed without assuming a priori uniform boundedness of the path flows. Such a more general continuity result has a few important implications to the existence of simultaneous route-and-departure choice DUE without a priori boundedness of path flows, and to any numerical algorithm that allows convergence to be rigorously analyzed.

1 Introduction

Dynamic traffic assignment (DTA) is usually viewed as the descriptive modeling of time varying flows on vehicular networks consistent with established traffic flow. This paper is concerned with a specific type of dynamic traffic assignment known as continuous time simultaneous route-and-departure choice (SRDC) dynamic user equilibrium (DUE) for which unit travel cost, including early and late arrival penalties, is identical for those route and departure time choices selected by travelers between a given origin-destination pair. There are two essential components within the notion of DUE: (i) the mathematical expression of Nash-like equilibrium conditions, and (ii) a network performance model, which is, in effect, an embedded dynamic network loading (DNL) problem. The DNL relates closely to the effective path delay operator, which plays a pivotal role in any of the mathematical forms of DUE problem, including variational inequality (Friesz et al.,, 1993), differential variational inequality (Friesz et al.,, 2001; Friesz and Mookherjee,, 2006), and complementarity problems (Pang et al.,, 2011; Wie et al.,, 2002).

Continuity of the effective delay operator, as we study in this paper, is critical to the DUE models since it is necessary to the existence of dynamic user equilibria (Browder,, 1968; Han et al., 2013c, ; Zhu and Marcotte,, 2000), and it is the minimum regularity assumption required by many computational algorithms that support convergence analysis, such as the fixed point algorithm (Friesz et al.,, 2011, 2012), the descent direction method (Han and Lo,, 2003; Szeto and Lo,, 2004), and the projection method (Ukkusuri et al.,, 2012).

One way to model path delay in dynamic networks is that proposed by Friesz et al., (1993), who employ arc exit time functions together with a volume-dependent link traversal time function. Such a perspective on path delay has been referred to both as the link-delay model (LDM) and as the point queue model (PQM) (Daganzo,, 1994). Notice that despite the popular tendency among many scholars to refer to the Vickrey model (Vickrey,, 1969) as the point queue model, a careful literature search reveals that the name ‘point queue model’ was first suggested by Daganzo, (1994) to describe the explicit travel time function model, in other words, the link delay model proposed by Friesz et al., (1993). Since the Friesz et al., (1993) paper, conjectures but few results about the qualitative properties of the LDM/PQM delay operator have been published. One result that is needed for the study of dynamic user equilibrium existence as well as for analyses of DUE algorithms, when network loading is based on the LDM/PQM, is continuity of the effective path delay operator. It should be mentioned that Zhu and Marcotte, (2000) investigated a similar problem and showed the weak continuity of the path delay operator under the assumption that the path flows are a priori bounded, where those bounds do not arise from any behavioral argument or theory. In particular, we note that Theorem 5.1 of Zhu and Marcotte, (2000), which states the weak continuity of the delay operator, relies on the strong first-in-first-out (FIFO) assumption. Although the paper later stated that a sufficient condition for strong FIFO is uniform boundedness of path flows (path departure rates), it is not difficult to show that boundedness is also necessary to ensure strong FIFO. Effectively, the strong FIFO assumption is equivalent to the uniform boundedness of path flows.

Notably, this paper provides a more general continuity result, namely the path delay operator of interest is strongly continuous without the assumption of boundedness on path flows. Strong continuity without boundedness is central to the proof of SRDC DUE existence, and to the analyses of DUE algorithms. We point out that the simultaneous route-and-departure choice (SRDC) notion of DUE employs more general constraints relating path flows to a table of fixed trip volumes than the route choice (RC) DUE considered by Zhu and Marcotte, (2000). The boundedness assumption is less of an issue for the RC DUE by virtue of problem formulation: that is, for RC DUE, the travel demand constraints are of the following form:

| (1.1) |

where is the set of origin-destination pairs, is the set of paths connecting and is the departure rate along path . Furthermore, represents the rate (not volume) at which travelers leave origin with the intent of reaching destination at time ; each such trip rate is assumed to be bounded from above. Since (1.1) is imposed pointwise and every path flow is non-negative, we are assured that are automatically uniformly bounded. On the other hand, the SRDC user equilibrium imposes the following constraints on path flows:

| (1.2) |

where is the volume (not rate) of travelers departing node with the intent of reaching node . The integrals in (1.2) are interpreted in the sense of Lebesgue; hence, (1.2) alone is not enough to assure bounded path flows. This observation has been the major hurdle to providing existence without the invocation of bounds on path flows, and therefore, serves as the main motivation of our investigation of the continuity of the delay operator without assuming a priori boundedness on path flows.

2 Background and preliminaries

This paper is concerned with one type of dynamic traffic assignment (DTA) known as simultaneous route-and-departure choice dynamic user equilibrium for which unit travel cost, including early and late arrival penalties, is identical for those route and departure time choices selected by travelers between a given origin destination pair. Such a model is originally presented in Friesz et al., (1993) and discussed subsequently by Friesz et al., (2001, 2012, 2011), and Friesz and Mookherjee, (2006).

2.1 Dynamic user equilibrium and the path effective delay operator

We begin by considering a planning horizon . Let be the set of paths employed by road users. The most crucial ingredient of the DUE model is the path delay operator. Such an operator, denoted by

maps a given vector of departure rates to the collection of travel times. Each travel time is associated with a particular choice of route and departure time . The path delay operators usually do not take on any closed form, instead they can only be evaluated numerically through the dynamic network loading procedure. On top of the path delay operator we introduce the effective path delay operator which generalizes the notion of travel cost to include early or late arrival penalties. In this paper we consider the effective path delay operators of the following form.

| (2.3) |

where is the target arrival time. In our formulation the target time is allowed to depend on the user classes. We introduce the fixed trip matrix , where each is the fixed travel demand between origin-destination pair . Note that represents traffic volume, not flow. Finally we let to be the set of paths connecting origin-destination pair .

As mentioned earlier is the vector of path flows . We stipulate that each path flow is square integrable, that is

The set of feasible path flows is defined as

| (2.4) |

Let us also define the essential infimum of effective travel delays

The following definition of dynamic user equilibrium was first articulated by Friesz et al., (1993):

Definition 2.1.

(Dynamic user equilibrium). A vector of departure rates (path flows) is a dynamic user equilibrium if

We denote this equilibrium by .

Using measure theoretic arguments, Friesz et al., (1993) established that a dynamic user equilibrium is equivalent to the following variational inequality under suitable regularity conditions:

| (2.5) |

2.2 The link delay model

We shall consider a general network where and denote the set of arcs and the set of nodes, respectively. Additionally, we shall take the link traversal time to be a linear function of the arc volume at the time of entry. We describe arc volume as the sum of volumes associated with individual paths using this arc, that is

| (2.6) |

where denotes the volume on arc associated with path , and is set of all paths considered. Each path is taken to be the set of consecutive arcs that consitute the path; that is

Furthermore we shall make use of the arc-path incidence matrix

where

We also let the time to traverse arc for drivers who arrive at its entrance at time be denoted by .

It will be convenient to introduce cumulative exit flows :

where the notation employed has obvious and conformal definitions relative to that introduced previously. The following differential algebraic equation (DAE) system is another version of the DAE system employed by Friesz et al., (2011):

| (2.7) | ||||

| (2.8) |

Furthermore, we make the following definitions

| (2.9) |

where , also known as the path flow, is the rate of departure from the origin of . It is also conventional to introduce the link exit time function

for each .

The next theorem, from Friesz et al., (1993), presents an important property of linear link delay functions:

Theorem 2.2.

For any linear arc delay function of the form , the resulting arc exit time function is continuous and strictly increasing and hence the inverse function exists.

Proof.

See Theorem 1 of Friesz et al., (1993). ∎

3 The main result

The following is a statement of our main result:

Theorem 3.1.

Consider a general network , where arc dynamics are governed by the link delay model, assume the link delay function for each is affine. That is

where and . Then the effective delay operator from into is a continuous map.

Remark 3.2.

In Zhu and Marcotte, (2000), the authors show that the effective delay operator is weakly continuous when the LDM is employed, under the restrictive assumption that the path flows are a priori bounded from above. Such assumption is dropped in our result; we also assert strong, not weak continuity.

The continuity result for the effective delay operator from Theorem 3.1 is crucial for the analysis and computation of dynamic user equilibrium, especially when a priori upper bound on the path flows is not guaranteed by any behavioral or mathematical arguments.

3.1 Proof of the main result

Now we present the proof of Theorem 3.1.

Proof.

We begin by showing that given a converging sequence in the space such that

| (3.10) |

the corresponding delay function converges uniformly to for all . This will be proved in several steps.

Part 1. First, let us consider just one single arc, and hence omit the subscript for brevity. Assume a sequence of entering flows converging to in the space; that is

| (3.11) |

Define the cumulative entering vehicle counts

Then we assert the uniform convergence on . To see this, fix any , in view of (3.11), choose such that for all

According to the embedding of into , we deduce for any that

The preceding shows the uniform convergence on .

Part 2. We adapt the recursive technique devised in Friesz et al., (1993). Let , , and denote the arc volumes corresponding to and , respectively. Assume, without loss of generality, that

and that, for the flow profile , the first vehicle enters the arc of interest at time . In addition, let denote the time that first vehicle exits the arc of interest. By definition

| (3.12) |

For all , since no vehicle can exit the arc before time , we have

| (3.13) |

For each flow profile , denote the exit time function restricted to by . Under the flow profile , denote the exit time function restricted to by . Then

| (3.14) | ||||

| (3.15) |

We conclude that uniformly on . Now let

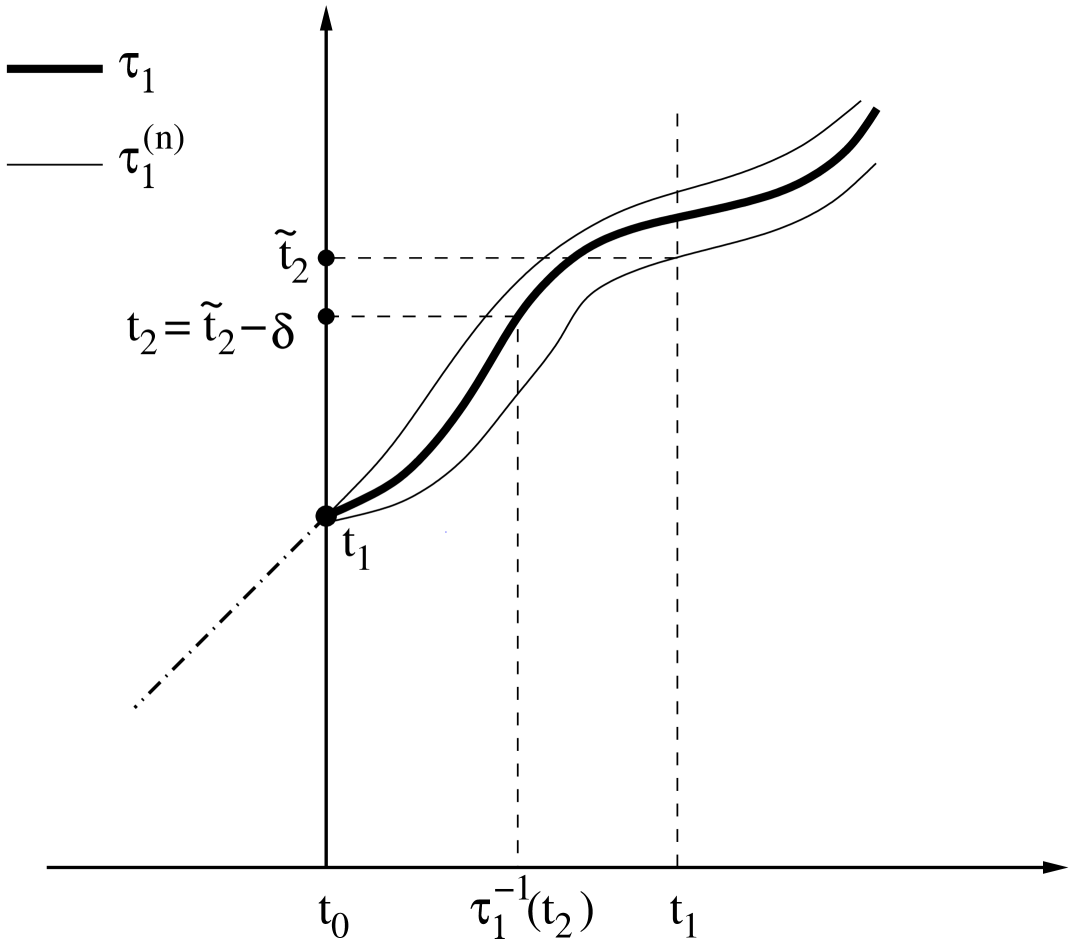

Fix small enough and call . See Figure 1 for a graphical illustration of these notations. By Theorem 2.2 the functions , , and , are well-defined, continuous and strictly increasing. We claim that uniformly converges to on . To see this, we need to extend the arrival time function and to the interval . Because no vehicle is present during , it is natural to assign

This means, if an infinitesimal flow particle enters the arc at , its travel delay will always be . Fix any , and consider the following quantities:

| (3.16) |

Since the infimum of a continuous function on a compact interval must be obtained at some point , we conclude by the strict monotonicity of established in Theorem 2.2.

According to the uniform convergence on , there exists some such that as soon as , we have

| (3.17) |

For any , we have . Therefor, for all , in view of (3.17) and (3.16), we have

By the Intermediate Value Theorem, there exists some with . In other words, we know

This finishes our claim that uniformly on .

Let and be the exit time functions for commuters entering during the interval , corresponding to entering flow profiles and , respectively. Then for each , we may state

| (3.18) | ||||

| (3.19) |

Now we make the claim that uniformly on . Indeed, for any , there exists such that, if , we have

Moreover, the functions , , and have a uniformly bounded range on , namely . By the Heine-Cantor theorem, restricted to is uniformly continuous, which means we can find such that, for any with , the following holds:

By uniform convergence of , we may choose so that, for , we have

Thus we deduce that, given , for any , the following is true:

This shows the uniform convergence on , and our claim is substantiated. As an immediate consequence of (3.18) and (3.19), converges to uniformly on .

Part 3. We now proceed by induction as follows. Choose any , and call

where the constant is the same as what was used in Part 2. Using the induction hypothesis that converges to uniformly on , we show the following uniform convergence on :

The proof is similar to what has been done in Part 2. Now introduce , , and , which are the exit time functions corresponding to and respectively; and they are restricted to the time interval . Similar to results (3.18) and (3.19), we have for , that the following holds:

| (3.20) | ||||

| (3.21) |

It can be shown as before that uniformly on . Therefore uniformly on . This finishes the induction.

Part 4. We now have obtained a sequence of intervals. On each interval , the uniform convergence

holds. Notice that, by construction, , ; therefore the interval can be covered by finitely many such intervals. As a consequence, we easily obtain the uniform convergence of on the whole of , where corresponds to and corresponds to .

Let , , and be the exit flows of the single arc and then define the cumulative exit vehicle count

It then follows immediately from the relationships

that converges uniformly to on .

Part 5. Consider a general network with a converging sequence in . Define for the following:

Then the converge uniformly to . For each arc , where the notation employed has an obvious meaning, the cumulative entering vehicle count is given by

In the above, the first summation is over all paths that use as the first arc; and, in the second summation, denotes the set of arcs immediately upstream from arc . A simple mathematical induction with the results established in previous steps yields the uniform convergence

where is the exit time function of arc . Thus, for each path , the path delay also converges uniformly to since it is a finite sum of arc delays. It remains to show that the effective delays obey uniformly on . Recall

Notice that is uniformly continuous on by the Heine-Cantor theorem; this means, for any , there exists such that whenever , we have

Moreover, by uniform convergence, there exits such that, for all , we have

We then readily deduce that, given , the following holds for all :

Part 6. Finally, uniform convergence on the compact interval implies convergence in the norm:

| (3.22) |

Summing up (3.22) over , we obtain the convergence in the Hilbert space . ∎

In some analysis (Bressan and Han,, 2013; Han et al.,, 2015) a slightly different notion of continuity of the effective delay operator is invoked as follows.

Definition 3.3.

(A-continuity) We say that the effective path delay operator is A-continuous if, for any weakly convergent sequence such that for any and where is some fixed constant, the effective path delays converges uniformly to for each .

As the following corollary asserts, the A-continuity also holds for the effective path delay operator.

Corollary 3.4.

Under the same assumption made in Theorem 3.1, the effective delay operator is A-continuous.

Proof.

Given any weakly convergent sequence such that for any and , we define

Then one immediately has that converges to uniformly on . Then the rest of the proof is the same as Part 2 - Part 6 of the proof of Theorem 3.1. ∎

4 Concluding remarks

Dynamic traffic assignment differs from static traffic assignment in that path delay does not enjoy a closed form. In fact the path delays needed for the study of dynamic user equilibria (DUE) are operators that may only be specified numerically. Moreover, such path delay operators are based on the specific model of arc delay employed for network loading. We have considered in this paper path delay operators for the network loading procedure that is endogenous to Friesz et al. (1993) which has been referred to as the link delay model (LDM) and also as the point queue model (PQM). We have shown that LDM/PQM path delay operators are strongly continuous under the very mild assumption that the link traversal time function is affine. In addition, our proof of continuity relies on no ad hoc assumptions on the uniform boundedness of path flows. Combined with the results, Browder, (1968); Han et al., 2013a ; Han et al., 2013b ; Han et al., 2013c , an increasingly clear understanding of DUE based on different network performance models is emerging.

References

- Bressan and Han, (2013) Bressan, A., Han, K., 2013. Existence of optima and equilibria for traffic flow on networks. Networks and Heterogeneous Media 8 (3), 627-648.

- Browder, (1968) Browder FE (1968). The fixed point theory of multi-valued mappings in topological vector spaces. Math. Annalen 177: 283-301.

- Daganzo, (1994) Daganzo CF (1994). The cell transmission model. Part I: A simple dynamic representation of highway traffic. Transportation Research Part B 28(4): 269- 287.

- Friesz et al., (1993) Friesz TL, Bernstein D, Smith T, Tobin R, Wie B (1993). A variational inequality formulation of the dynamic network user equilibrium problem. Operations Research 41(1): 80-91.

- Friesz et al., (2001) Friesz TL, Bernstein D, Suo Z, Tobin R (2001). Dynamic network user equilibrium with state-dependent time lags. Network and Spatial Economics 1(3/4): 319-347.

- Friesz et al., (2012) Friesz TL, Han K, Neto PA, Meimand A, Yao T (2012). Dynamic user equilibrium based on a hydrodynamic model. Transportation Research Part B, 47(1): 102-126.

- Friesz et al., (2011) Friesz TL, Kim T, Kwon C, Rigdon MA (2010). Approximate network loading and dual-time-scale dynamic user equilibrium. Transportation Research Part B 45: 176-207.

- Friesz and Mookherjee, (2006) Friesz TL, Mookherjee R (2006). Solving the dynamic network user equilibrium problem with state-dependent time shifts. Transportation Research Part B 40(3): 207-229.

- Han et al., (2015) Han, K., Friesz, T.L., Szeto, W.Y., Liu, H., 2015. Dynamic user equilibrium with elastic demand: formulation, qualitative analysis and computation. Preprint available at http://arxiv.org/abs/1304.5286

- (10) Han K, Friesz TL, Yao T (2013a). A partial differential equation formulation of Vickrey s bottleneck model, part I: Methodology and theoretical analysis. Transportation Research Part B 49: 55-74.

- (11) Han K, Friesz TL, Yao T (2013b). A partial differential equation formulation of Vickrey s bottleneck model, part II: Numerical analysis and computation. Transportation Research Part B 49: 75-93.

- (12) Han K, Friesz TL, Yao T (2013c). Existence of simultaneous route and departure choice dynamic user equilibrium. Transportation Research Part B 53: 17-30.

- Han and Lo, (2003) Han D, Lo HK (2003). Solving nonadditive traffic assignment problems: a decent method for co-coercive variational inequalities. European Journal of Operational Research 159: 529-544.

- Pang et al., (2011) Pang J, Han L, Ramadurai G, Ukkusuri S (2011). A continuous-time linear complementarity system for dynamic user equilibria in single bottleneck traffic flows. Mathematical Programming, Series A 133(1-2): 437-460.

- Szeto and Lo, (2004) Szeto WY, Lo, HK (2004). A cell-based simultaneous route and departure time choice model with elastic demand. Transportation Research Part B 38: 593-612.

- Ukkusuri et al., (2012) Ukkusuri S, Han L, Doan K (2012). Dynamic user equilibrium with a path based cell transmission model for general traffic networks. Transportation Research Part B 46(10): 1657-1684.

- Vickrey, (1969) Vickrey WS (1969). Congestion theory and transport investment. The American Economic Review 59(2): 251-261.

- Wie et al., (2002) Wie BW, Tobin RL, Carey M (2002). The existence, uniqueness and computation of an arc-based dynamic network user equilibrium formulation. Transportation Research Part B 36(10): 897-918.

- Zhu and Marcotte, (2000) Zhu DL, Marcotte P (2000). On the existence of solutions to the dynamic user equilibrium problem. Transportation Science 34(4): 402-414.