Cosmological 21cm line observations to test scenarios of super-Eddington accretion on to black holes being seeds of high-redshifted supermassive black holes

Abstract

In this paper, we study scenarios of the super-Eddington accretion onto black holes at high redshifts , which are expected to be seeds to evolve to supermassive black holes until redshift . For an initial mass, of a seed BH, we definitely need the super-Eddington accretion, which can be applicable to both astrophysical and primordial origins. Such an accretion disk inevitably emitted high-energy photons which had heated the cosmological plasma of the inter-galactic medium continuously from high redshifts. In this case, the cosmic history of cosmological gas temperature is modified, by which the absorption feature of the cosmological 21 cm lines is suppressed. By comparing theoretical predictions of the 21cm line absorption with the observational data at , we obtain a cosmological upper bound on the mass-accretion rate as a function of the seed BH masses. In order to realize at by a continuous mass-accretion on to a seed BH, to be consistent with the cosmological 21cm line absorption at , we obtained an severe upper bound on the initial mass of the seed BH to be () when we assume a seed BH with its comoving number density (). We also discuss some implications for application to primordial black holes as the seed black holes.

I Introduction

Quite recently a luminous quasar (QSO) J0313-1806 was observed at redshift = 7.642 Wang:2021apjl . The mass of the central black hole (BH) in this QSO system is quite large . In addition to this BH, so far several QSOs at around 7 have been already reported, each of which has a massive central BH similarly with the order of . In astronomy and astrophysics, it is a big challenge to produce such supermassive black holes (SMBHs) in an early Universe within cosmic time Gyr. 111Here we used the Hubble parameter , the omega parameters of matter, and cosmological constant as reference values.

One of the most natural scenarios to increase a BH mass to a massive one should be a gas accretion on to it. However, even if the Eddington accretion is realized, there is no easy solution. For example, when we assume the Eddington accretion rate is successively-continuing with a radiative efficiency from cosmic time Gyr Barkana:2000fd to Gyr, the seed mass at should be in order to obtain until . Therefore, even if we assume the Eddington accretion rate, we need a massive seed as an initial condition Woods:2018lty ; Inayoshi:2019fun . Possible scenarios to produce such massive seed BHs have been studied, e.g., through collapses of massive stars/gas clouds, or through mergers of massive stars/ black holes Loeb:1994wv ; Omukai:2000ic ; Oh:2001ex ; Volonteri:2005fj ; Lodato:2006hw ; Wise:2007bf ; Regan:2008rv ; Shang:2009ij ; Volonteri:2010wz ; Hosokawa:2012uq ; Inayoshi:2012zi ; Latif:2013pyq ; Hosokawa:2013mba ; Regan:2014maa ; Inayoshi:2014rda ; Ferrara:2014wua ; Becerra:2014xea ; Latif:2015eoa ; Chon:2016nmh ; wise:2019nature ; Becerra:2018mnras ; Maio:2018sfz ; Mayer:2017nature ; Mayer:2018gyh ; Mayer:2014nva ; Dijkstra:2014mnras ; Sugimura:2014sqa ; Wolcott-Green:2016grm ; Wolcott-Green:2020avn ; Chon:2018mnras ; Matsukoba:2018qxr ; Bromm:2002hb ; Spaans:2006ur ; Sanders:1970 ; PortegiesZwart:2002iks ; PortegiesZwart:2004ggg ; Freitag:2005yd ; Omukai:2008wv ; Devecchi:2009 ; Devecchi:2012nw ; katz:2015 ; Sakurai:2017opi ; Stone:2016ryd ; Reinoso:2018bfv ; Tagawa:2019vep ; Boekholt:2018gbw ; yajima:2016mnras ; Davies:2011pd ; Lupi:2015wxp . Alternatively, those massive seeds may be formed through other primordial origins such as primordial black holes Kawasaki:2012kn ; Kohri:2014lza ; Nakama:2016kfq ; Serpico:2020ehh ; Unal:2020mts (See also Refs. Carr:2009jm ; Green:2020jor ; Carr:2021bzv ; Carr:2020gox for review articles). Another possibility would be assuming a super-Eddington accretion rate 222 For concrete models of the super-Eddington accretion, see references for the slim disk models Watarai:2000 ; Watarai:2003tr ; Yuan:2014gma , the neutrino-dominated accretion flows Kohri:2002kz ; Kohri:2005tq , etc. and references therein. on to a light seed BH Begelman:1978 ; Sadowski:2009gg ; Wyithe:2012 ; Madau:2014pta ; Inayoshi:2015pox ; Pezzulli:2016 ; Pezzulli:2017ikf ; Begelman:2016gle ; Alexander:2014 ; Pacucci:2017mcu ; Mayer:2018gyh ; Takeo:2020vmm ; natarajan:2021 . 333See also Ref. Ebisuzaki:2001qm for another mechanism through mergers of seed BHs which were produced by mergers of massive stars.

To test consistencies of the theoretical disk models for the (super-)Eddington accretions with observations, in principle we can use cosmological 21cm line emissions/absorptions which were produced in the dark ages at (e.g., see Tanaka:2015sba ; Ewall-Wice:2018bzf ; Sazonov:2018tnj ; Ewall-Wice:2019may ; Ma:2021pgp for earlier works). So far, the EDGES collaboration has reported the observational data for the absorption feature of the cosmological global 21cm line spectrum at around Bowman:2018yin . If there existed an extra heating source due to emissions from the accretion disks in this epoch, gas temperature could be larger than the standard value predicted in the standard -cold dark matter (CDM) model. In this case, a depth of the 21cm line absorption should have become shallower than the one in the CDM model. Because the EDGES collaboration reported the large depth with finite errors, we can test this kind of scenarios and obtain a conservative upper bound on such an extra emission at least not to bury the observed absorption trough DAmico:2018sxd ; Hiroshima:2021bxn . It is known that a cosmological extra heating of the order of at affects the absorption feature of the global 21cm line spectrum (e.g., see Ref. Hiroshima:2021bxn and references therein). In this paper, by using this logic, we discuss how we can constrain the scenarios of the (super-)Eddington accretions onto high-redshifted seed BHs which are expected to evolve to the SMBHs until and obtain observational bounds on the accretion rates.

This paper is organized as follows. In Sec. II, we review how energy injection affects evolution of the intergalactic medium (IGM). Models of accretion disks are introduced in Sec. III. In Sec. IV, we discuss energy injections from accretions onto seed black holes. In Sec. V, we present our results. We conclude in the final section VI.

Throughout the paper, we adopt the Heaviside–Lorentz units of unless otherwise stated.

II Evolution equations of IGM in the presence of energy injection

In this section, we explain how energy injection affects evolutions of the IGM. For illustrative purposes, we follow a simple description of hydrogen in the IGM, which is based on the effective three-level atom Peebles:1968ja ; Zeldovich:1969en ; Seager:1999km . As will be shown in Sec V however, we actually execute the public recombination code HyRec444https://pages.jh.edu/~yalihai1/hyrec/hyrec.html, which is based on the state-of-art effective multi-level atom (See AliHaimoud:2010dx ; Chluba:2010ca ). In this study, for simplicity we focus only on ionization and recombination of hydrogen while assuming helium is neutral. It is known that this simplification is a good approximation as long as we are interested in processes that occurred in the cosmic dark ages (Dark Ages) Liu:2016cnk (See also Liu:2019bbm ).

The cosmic evolution of the ionization fraction, , is then described by the following equation:

| (1) | |||||

where and are the temperatures of gas and photon, respectively. is the number density of hydrogen, is the ionization energy of hydrogen, and is the energy of Ly-. Here is the case-B recombination coefficient, and is the corresponding ionization rate. The Peebles’ -factor (), represents the probability that a hydrogen atom initially in the shell reaches the ground state without being photoionized. It is given by

| (2) |

where s-1 is the two-photon decay rate of the hydrogen 2-state, and is the Hubble expansion rate. The last term in (1) represents the effects of energy injection with the energy injection rate per unit volume per time, , which will be shown in detail in the next section.

Evolutions of the gas temperature is described by the following equation:

| (3) |

where is the coupling rate of to , which is dominated by the Compton scattering,

| (4) |

where is the Thomson scattering cross section, is radiation constant, is the electron mass, and is the number ratio of helium to hydrogen. The last term in (3) represents heating of the gas temperature due to the energy injection. As defined in Slatyer:2015jla ; Slatyer:2015kla the coefficients , , and (collectively denoted by hereafter) are the fractions of injected energy deposited into the hydrogen ionization, the hydrogen excitation, and the heating of gas, respectively.

III Models of accretion disks

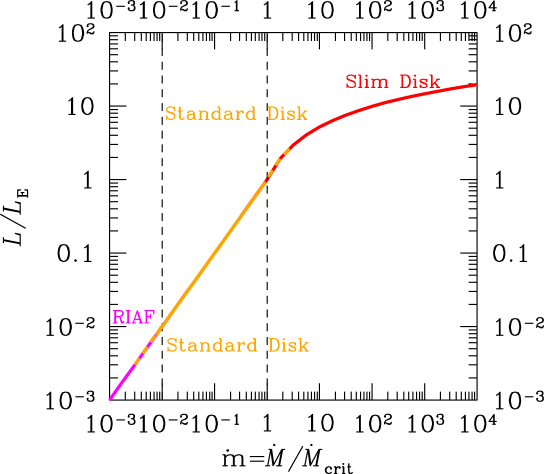

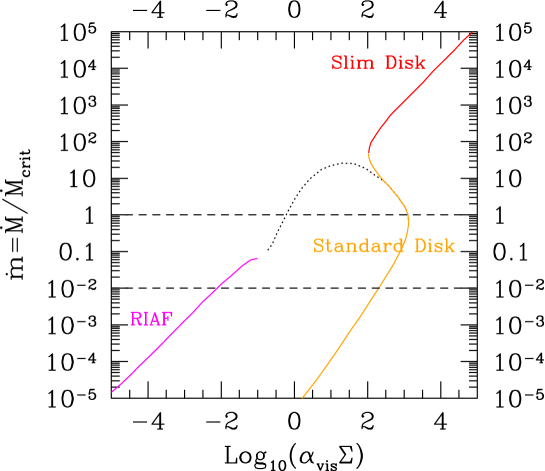

In Fig. 1, we plot the luminosity from the accretion disks as a function of the accretion rate in case of the viscous parameter (=0.1) in the unified picture of the three models (see Fig. 2) Yuan:2014gma , RIAF (Radiation Inefficient Accretion Flow) (), the standard disk ()), and the slim disk (). The luminosity is normalized by the Eddington luminosity,

| (5) |

where denotes Solar mass g). The accretion rate is normalized by the critical accretion rate, to be

| (6) |

where with the radiative efficiently , which ranges in the standard disk and the slim disk models Watarai:2000 ; Mineshige:2008 , and approximately in the RIAF model with Yuan:2014gma . In this study, for simplicity we take as a reference value. Then the critical accretion rate is represented by

| (7) |

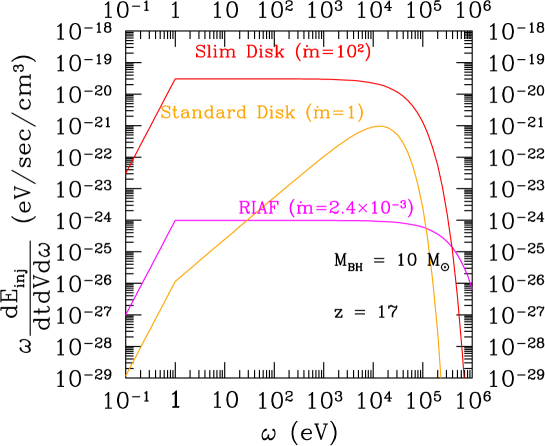

The spectrum of the emissivity in each model is approximately parametrized by the following function form,

| (8) |

with the photon energy , being the normalization factor in unit of erg sec-1 eV-1 to be consistent with the curve plotted in Fig. 1. These parameters are fitted to be the values shown in Table I (See Refs. Watarai:2000 ; Yuan:2014gma ; Mineshige:2008 ).

| RIAF | Standard disk | Slim disk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| in eV | 1 | 1 | |

| -1 | 1/3 | -1 | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| in keV | 200 | 10 | 10 |

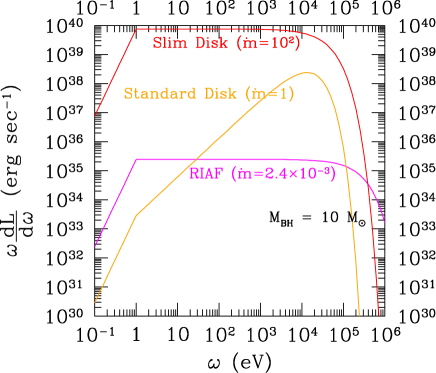

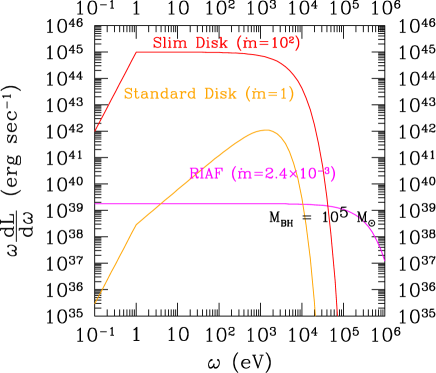

In Fig. 3, we plot as a function of the energy in eV for = 10 (left) and = (right). 555See also Ref. Kawanaka:2020uen for possible modifications of the spectrum for the slim disk through the Inverse Compton scattering by energetic electron in coronae. In order to observationally confirm the shape of the spectra, we also have to additionally consider possible absorptions of soft X-rays by Compton absorbers. It is interesting that we can trace such absorbers by measuring neutral hydrogen with column density by future low-redshifted 21 cm observations Moss:2017 ; Ursini:2017ixb ; Curran:2018 ; Hickox:2018xjf ; Morganti:2018 ; Liszt:2020 .

IV Energy injection and deposition into the IGM from accretion disks

The energy injection rate is given as

| (9) |

with

| (10) |

where is the number density of the seed BHs as a function of , which are expected to be evolved to SMBHs in a late epoch. Then, we parametrize the form of to be

| (11) |

with the comoving number density of the seed BHs . This equation requires careful attention to the actual meaning of . Surely it is equal to at face value. However, it is notable that can increase at a later time as a function of cosmic time, depending on models, e.g., for . For each value of thus, we take it to be constant at least from to . Here we may take a maximum value of it possibly to be which is derived roughly by assuming that every (massive) galaxy at least had a seed BH in its center in the comoving coordinate () Serpico:2020ehh , with the energy density of cold dark matter (CDM) , the reduced Hubble constant , and being a typical mass of a massive galaxy (). This value of is consistent with the observations of the SMBHs at Williot:2010waa ; Tanaka:2015sba . On the other hand, as a conservative limit of it, we may take to fit some observations of the SMBHs at around Williot:2010waa . 666In this case, we assume that the number density of the seed BHs does not increase much from to . In this latter case, it is interpreted that the main components of the seeds were produced at a late time . Because we cannot judge which value of the normalization of is more correct, in the current study therefore, we adopt some representative values by changing it in the range of as an initial value of the comoving number density set at a higher redshift and study the effect in each case. In Fig. 4, we plot as a function of the energy in eV at . Here we took and = 10 as a reference.

To compute the deposition fractions , we need detailed information about both the spectrum of photon emitted from accretion disks and processes of their interactions with the IGM. The authors of Refs. Shull:1985 ; Chen:2003gz ; Padmanabhan:2005es ; Ripamonti:2006gq ; Kanzaki:2008qb ; Slatyer:2009yq ; Kanzaki:2009hf ; Evoli:2012zz studied how those energetic photons lose their energy through interaction processes with the IGM and affect ionization and heating of the IGM. A typical timescale of energy-loss processes for photons with their energy ranges can be longer than the Hubble time. This requires detailed computation of the energy deposition fully over cosmological time scales. Here we adopt ways of computations done in Ref. Slatyer:2015kla 777https://faun.rc.fas.harvard.edu/epsilon/, in which the effects of energy injection is treated at a linear level, i.e, omitting higher-order nonlinear terms. For full treatments including feedback of the modification of the IGM evolution in the computation of , we refer to Ref. Liu:2019bbm .

By using Eqs.(9), (10) and (11), we can estimate the energy injection rate analytically to be

| (12) |

It has been known that this order-of-magnitude energy injection rate () should have affected the absorption feature of the global 21cm line spectrum at around Hiroshima:2021bxn . 888 see also Refs.Poulin:2016anj ; DAmico:2018sxd ; Mena:2019nhm ; Liu:2020wqz ; Bolliet:2020ofj . This means that we see intuitively that the (super-)Eddington accretion rate [] can be highly constrained for in case of by observational data of the cosmological 21cm line absorption.

The time evolution of is solved to be

| (13) |

where at with a constant and a possible suppression factor Sassano:2021maj ; Pacucci:2021ubg due to efficiencies for a continuous accretion and so on. We adopt as a simple reference value in this study. Here the timescale of the Eddington accretion is given by

| (14) |

V Results

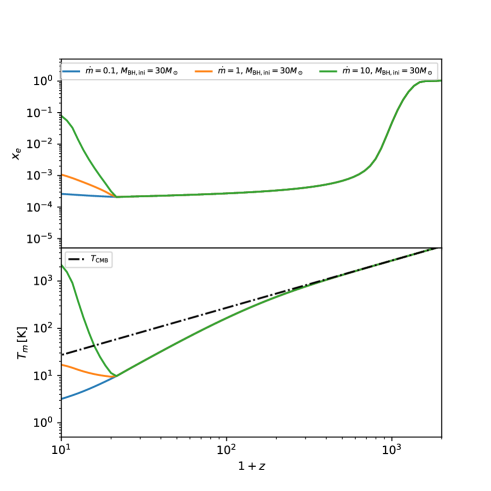

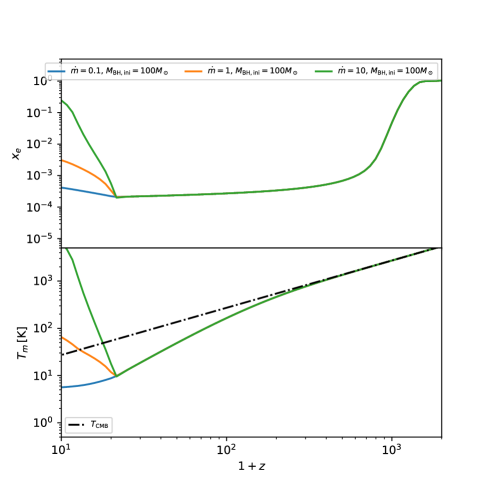

In Fig. 5, the evolutions of and are shown as a function of redshift in case with the emission from accretion disk, which started from the initial redshift . Here we assumed there is no significant heating from the other astrophysical sources.

|

|

Compared to cases where such an energy injection is absent, the gas temperatures is highly enhanced. This is due to the extra heating by photons emitted from the accretion disks, which modified the evolution of the spin temperature, , associated with the hyperfine splitting in the ground states of neutral hydrogen. This allows us to constrain emission from accretion disks from observations of differential brightness temperature of redshifted 21 cm line emission before reionization (See e.g. Furlanetto:2006jb ),

| (15) |

A time-evolution of the spin temperature is controlled by relative couplings of with the photon temperature , the gas temperature , and the color temperature , which is the effective temperature associated with background Lyman- radiation. Throughout the epoch we are currently studying, the IGM is fully optically thick for emissions of Lyman- radiation. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume . The EDGES collaboration reported a global absorption (not emission) signal Bowman:2018yin

| (16) |

which means the gas temperature is smaller than the photon temperature . Here we considered the delayed deposition which was studied in Ref. Liu:2018uzy ; Basu:2020qoe . 999The optical depth for the X-ray with a few keV highly depends on redshifts with a rapidly-changing function of , and accidentally becomes O(1) at = 10 – 30. This is clearly shown in literature, e.g., Fig.2 of Ref. Chen:2003gz and Fig.3 of Ref. Slatyer:2015kla . Therefore, to be thermalized for the emitted X-rays, we need a time of the order of or even much longer than the Hubble time at that time. That is the reason why the thermalization was not realized immediately and got delayed.

In general, photon emissions from accretion disks suppress the amplitude of the absorption for the global 21cm signals by ionizing and heating the IGM. It is reasonable to assume a tight coupling of spin temperature to gas temperature through the Lyman- pumping (the Wouthuysen-Field effect Wouthuysen:1952 ; Field:1959 ). This maximizes the absorption depth, which gives the most conservative limit on extra-photon emissions. In addition, we did not assume other ambiguous astrophysical heating sources such as UV emissions from stars formed by non-standard CDM halo formations at small scales, annihilating/decaying dark matter, and so on, that also helps to obtain the most conservative upper bound on it. The prediction in the standard CDM model without such a heating by the accretion disks gives (e.g., see Ref. Hiroshima:2021bxn ). We obtain an upper bound on the photon emissions from accretion rate by requiring , which correspond to the 2 upper bound on it with given uncertainties of the EDGES ( mK) at 95 C.L. Hiroshima:2021bxn Here we did not assume any exotic cooling mechanisms such as interaction between baryon and CDM only to fit the observational depth of the absorption feature reported by EDGES (see also DAmico:2018sxd ). 101010Quite recently the SARAS 3 collaboration reported that they rejected the signal by the EDGES at 95.3 C.L. Singh:2021mxo . In this paper however, we only use the sensitivity on the errors (not the signal of the absorption feature) of the EDGES, which is not inconsistent with the claim by the SARAS 3. See similar discussions, e.g., in Ref. Saha:2021pqf .

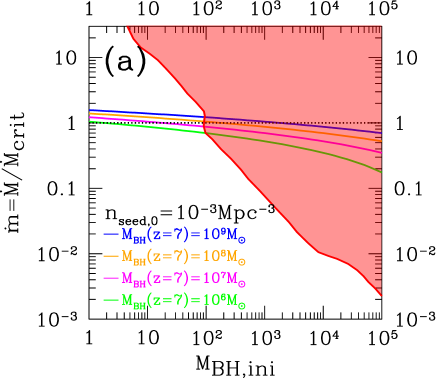

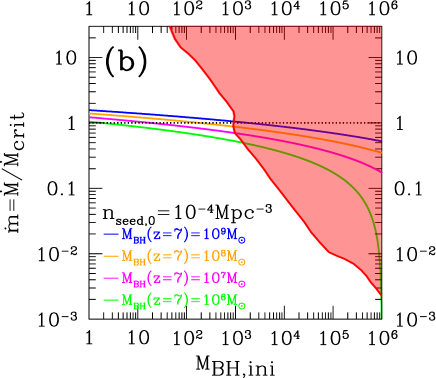

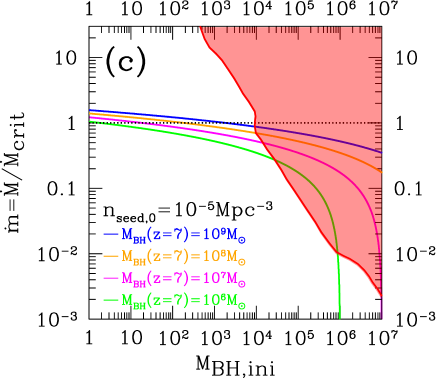

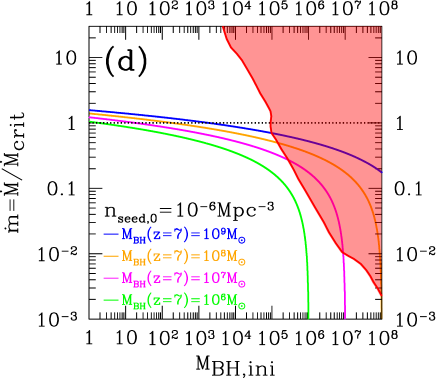

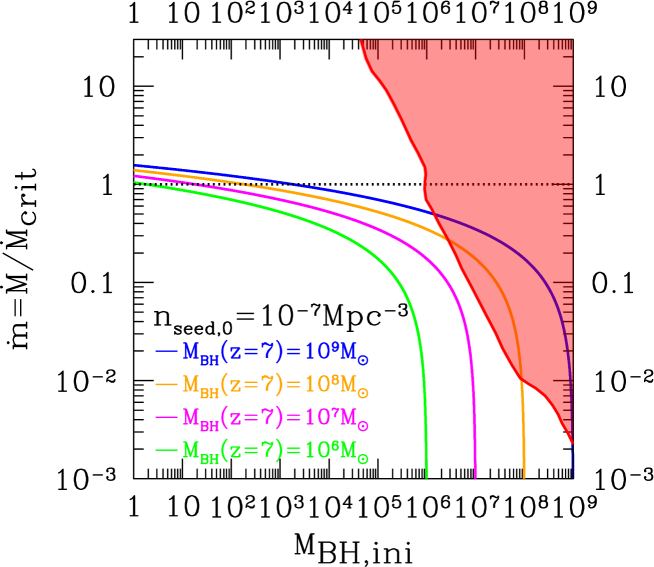

In Fig. 6, we show the upper bound on the accretion rate as a function of the initial seed BH mass () conservatively-obtained in this study, which means that the shaded region (the upper-right region) is excluded for chosen to be (a) , (b) , (c) , and (d) . The blue, orange, magenta, and green solid lines denote the conditions given in Eq. (13), on which successfully , , , and are realized at with and , respectively. In case of or , readers can read off a value of the -axis by using the scaling law of it . 111111We do not use the data reported by the HERA Phase 1 to obtain the mild lower bound on 21cm emissions at around . HERA:2021bsv because it does not constrain any model parameter in the current setup where we have not specified when the standard processes of the cosmological reionization occurred. Here we have chosen the reference value of the initial redshift to be after that the accretion had started by following the discussions in Bromm:2013iya . Even if we adopted a larger value of , the obtained bound becomes much stronger. Thus, our current choice gives a conservative bounds on the plane of (, ). A more comprehensive analysis by studying every case with changing those values is outside the scope of the current paper.

In case of the maximum value of shown in Fig. 6(a), to satisfy the condition for the successful SMBH formation with at , the initial masses of seed BHs have been excluded for at 95 C.L. Therefore, the reference value of the initial seed mass with the just-on Eddington accretion rate is apparently excluded in this case. This means that we inevitably need the super-Eddington accretion rate for lighter-mass seed BHs, .

In Fig. 7, we plot the excluded region when we adopt the most conservative case, . From this figure, we find that the initial mass of the seed BHs for are allowed at 95 C.L. to obtain at . In this case, we need for continuous accretions on to the initial seed mass set at until .

From Fig. 6 and Fig. 7, readers can read off every constraint by changing . For example, according to information of Fig. 8 of Ref. Williot:2010waa , to realize until with we can see are allowed at 95 C.L. from the magenta line in Fig. 6(c).

In Fig. 8, we plot the lines of the conditions to realize , , , in the 2D plane of the initial BH mass set at and the comoving number density of the seed BHs in case of (a) , and (b) . The upper-right regions (red regions) are excluded by the observational bounds on the 21 cm lines at around . From Fig. 8(a), to realize , we find that is excluded for . This means that we need another mechanism to create the seed BHs after . On the other hand, from Fig. 8(b), we obtained the conservative upper limit on to be with the minimum mass-accretion rate to realize for a conservative lower limit on the comoving number density of the seed BHs .

It is notable that those bounds can be applicable to scenarios for accretions on to primordial black holes (PBHs) like as floating BHs, which were produced at . 121212We can refer to papers for the other aspects of researches about the PBHs constrained from 21cm line observations for cosmological accretions on to PBHs Gong:2017sie ; Gong:2018sos ; Hektor:2018qqw ; Mena:2019nhm ; Hutsi:2019hlw ; Hasinger:2020ptw ; Villanueva-Domingo:2021cgh ; Yang:2021idt ; Yang:2021agk ; Acharya:2022txp and evaporation of PBHs Mack:2008nv ; Carr:2009jm ; Clark:2018ghm ; Carr:2020gox ; Halder:2021jiv ; Natwariya:2021xki ; Mittal:2021egv ; Cang:2021owu ; Saha:2021pqf . Those BHs could enter into halos by chance and be surrounded by dense gas at higher redshifts. In this case, the cosmological omega parameter of the seed BHs () is related to by

| (17) |

with the mass of SMBHs. Then, has two meanings: 1) the mass of a BH which was originally equal to it, or 2) which had evolved to this value by an accretion until . This parametrization also requires careful attention to the meaning of (or ) here. It is different from the usual definition of the cosmological omega parameter for the homogeneously-distributed field component of the BHs, but for the one inside halos surrounded by rich gas. Actually it should be highly model-dependent to estimate the real fraction of such seed BHs captured into this kind of systems to the total BHs.

VI Conclusion

In this paper we have studied the scenarios of the accretions on to black holes from sub- to super- Eddington rates at high redshifts which are expected to become seeds to evolve to supermassive black holes until redshift . Such an accretion disk emits copious high-energy photons (the UV and keV-MeV photons) which had heated the plasma of the intergalactic medium continuously at high redshifts. In this case, the gas temperature is modified, by which the absorption of the cosmological 21 cm lines are suppressed at around .

As is shown in Fig. 6 and Fig. 7, by comparing the theoretical prediction of the global cosmological 21cm line absorption with the signal observed by the EDGES collaboration, conservatively we have obtained the upper bounds on the mass-accretion rate on to each initial seed black hole set at . If we adopted a maximum value for the comoving number density of the seed BH to be shown in Fig.7, in order to satisfy the successful formations of the supermassive black holes until , we obtained the upper bound on the seed-BH masses to be . Clearly the reference model with the exact Eddington accretion rate () is excluded. In other words, for a seed BH mass smaller than we inevitably need the super-Eddington accretion. Alternatively, such a high accretion on to a larger seed mass () should have started after .

On the other hand, if we adopted a conservative value for the comoving number density of the seed BH, to fit the observations of SMBHs partly with at Williot:2010waa , we obtain a milder bound on the initial seed mass, . In this latter case, we only need a sub-Eddington rate for .

This constraint is applicable to scenarios for accretions on to primordial black holes (PBHs) and so on. Then, the cosmological omega parameter of the seed PBHs,i.e., (not the homogeneously-distributed field component of the PBHs, ) is related to approximately by .

In future, more precise data of high-redshifted 21cm lines will be reported by HERA Beardsley:2014bea , SKA SKAspec , Omniscope Omniscope or DAPPER Burns:2021ndk . By adopting those data, then we will be able to detect signatures of the super-Eddington accretion on to the seed BHs to evolve to the high-redshifted SMBHs.

Acknowledgements.

We thank Kohei Inayoshi, Norita Kawanaka, Koutarou Kyutoku, Vivian Poulin and Pasquale D. Serpico for useful discussions. This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP17H01131 (K.K. and T.S.), JP15H02082 (T.S.), JP18H04339 (T.S.), JP18K03640 (T.S.), and MEXT KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP19H05114 (K.K.), JP20H04750 (K.K.). S.W. is partially supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China with Grant No. 12175243, the Institute of High Energy Physics with Grant No. Y954040101, and the Key Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences with Grant No. XDPB15. Numerical computations were carried out on Cray XC50 at Center for Computational Astrophysics, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan.References

- (1) F. Wang et al, Astrophys. J. Lett. 907L (2021) 1 [arXiv:2101.03179 [astro-ph.GA]]

- (2) R. Barkana and A. Loeb, Phys. Rept. 349, 125-238 (2001) [arXiv:astro-ph/0010468 [astro-ph]].

- (3) T. E. Woods, B. Agarwal, V. Bromm, A. Bunker, K. J. Chen, S. Chon, A. Ferrara, S. C. O. Glover, L. Haemmerlé and Z. Haiman, et al. Publ. Astron. Soc. Austral. 36, e027 (2019) [arXiv:1810.12310 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (4) K. Inayoshi, E. Visbal and Z. Haiman, Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 58, 27-97 (2020) [arXiv:1911.05791 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (5) A. Loeb and F. A. Rasio, Astrophys. J. 432, 52 (1994) [arXiv:astro-ph/9401026 [astro-ph]].

- (6) K. Omukai, Astrophys. J. 546, 635 (2001) [arXiv:astro-ph/0011446 [astro-ph]].

- (7) S. P. Oh and Z. Haiman, Astrophys. J. 569, 558 (2002) [arXiv:astro-ph/0108071 [astro-ph]].

- (8) G. Lodato and P. Natarajan, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 371, 1813-1823 (2006) [arXiv:astro-ph/0606159 [astro-ph]].

- (9) M. Volonteri and M. J. Rees, Astrophys. J. 633, 624-629 (2005) [arXiv:astro-ph/0506040 [astro-ph]].

- (10) K. Inayoshi and K. Omukai, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 422, 2539-2546 (2012) [arXiv:1202.5380 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (11) T. Hosokawa, H. W. Yorke, K. Inayoshi, K. Omukai and N. Yoshida, Astrophys. J. 778, 178 (2013) doi:10.1088/0004-637X/778/2/178 [arXiv:1308.4457 [astro-ph.SR]].

- (12) J. A. Regan, P. H. Johansson and J. H. Wise, Astrophys. J. 795, no.2, 137 (2014) [arXiv:1407.4472 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (13) K. Inayoshi, K. Omukai and E. J. Tasker, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 445, 109 (2014) [arXiv:1404.4630 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (14) A. Ferrara, S. Salvadori, B. Yue and D. R. G. Schleicher, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 443, no.3, 2410-2425 (2014) [arXiv:1406.6685 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (15) F. Becerra, T. H. Greif, V. Springel and L. Hernquist, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 446, 2380-2393 (2015) [arXiv:1409.3572 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (16) V. Bromm and A. Loeb, Astrophys. J. 596, 34-46 (2003) [arXiv:astro-ph/0212400 [astro-ph]].

- (17) J. H. Wise, M. J. Turk and T. Abel, Astrophys. J. 682, 745 (2008) [arXiv:0710.1678 [astro-ph]].

- (18) J. A. Regan and M. G. Haehnelt, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 396, 343 (2009) [arXiv:0810.2802 [astro-ph]].

- (19) C. Shang, G. Bryan and Z. Haiman, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 402, 1249 (2010) [arXiv:0906.4773 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (20) T. Hosokawa, K. Omukai and H. W. Yorke, Astrophys. J. 756, 93 (2012) [arXiv:1203.2613 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (21) M. A. Latif, D. R. G. Schleicher, W. Schmidt and J. C. Niemeyer, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 436, 2989 (2013) [arXiv:1309.1097 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (22) S. Chon, S. Hirano, T. Hosokawa and N. Yoshida, Astrophys. J. 832, no.2, 134 (2016) [arXiv:1603.08923 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (23) M. A. Latif, D. R. G. Schleicher and T. Hartwig, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 458 (2016) 233 [arXiv:1510.02788 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (24) F. Becerra F, F. Marinacci, V. Bromm, and L.E. Hernquist Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc, 480 (2018) 5029 [arXiv:1804.06413 [astro-ph.GA]]

- (25) J.H. Wise, J.A. Regan, B.W. O’Shea, M.L. Norman, T.P. Downes, H. Xu, Nature 566, 85 (2019)

- (26) U. Maio, S. Borgani, B. Ciardi and M. Petkova, Publ. Astron. Soc. Austral. 36, e020 (2019) [arXiv:1811.01964 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (27) L. Mayer, Nature Astron. 1, 0108 (2017)

- (28) L. Mayer and S. Bonoli, Rept. Prog. Phys. 82, no.1, 016901 (2019) [arXiv:1803.06391 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (29) L. Mayer, D. Fiacconi, S. Bonoli, T. Quinn, R. Roskar, S. Shen and J. Wadsley, Astrophys. J. 810, no.1, 51 (2015) [arXiv:1411.5683 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (30) M. Dijkstra, A. Ferrara, A. Mesinger, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc, 442 (2014) 2036

- (31) K. Sugimura, K. Omukai and A. K. Inoue, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 445, no.1, 544-553 (2014) [arXiv:1407.4039 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (32) J. Wolcott-Green, Z. Haiman and G. L. Bryan, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 469, no.3, 3329-3336 (2017) [arXiv:1609.02142 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (33) J. Wolcott-Green, Z. Haiman and G. L. Bryan, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 500, no.1, 138-144 (2020) [arXiv:2001.05498 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (34) S. Chon, T. Hosokawa, N. Yoshida, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 475, 4104 (2018)

- (35) R. Matsukoba, S. Z. Takahashi, K. Sugimura and K. Omukai, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 484, no.2, 2605-2619 (2019) [arXiv:1901.00007 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (36) M. Spaans and J. Silk, Astrophys. J. 652, 902-906 (2006) [arXiv:astro-ph/0601714 [astro-ph]].

- (37) D. B. Sanders, Astrophys. J. 162, 791 (1970)

- (38) S. F. Portegies Zwart and S. L. W. McMillan, Astrophys. J. 576, 899-907 (2002) [arXiv:astro-ph/0201055 [astro-ph]].

- (39) S. F. Portegies Zwart, H. Baumgardt, P. Hut, J. Makino and S. L. W. McMillan, Nature 428, 724 (2004) [arXiv:astro-ph/0402622 [astro-ph]].

- (40) M. Freitag, M. A. Gurkan and F. A. Rasio, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 368, 141-161 (2006) [arXiv:astro-ph/0503130 [astro-ph]].

- (41) K. Omukai, R. Schneider and Z. Haiman, Astrophys. J. 686, 801 (2008) [arXiv:0804.3141 [astro-ph]].

- (42) B. Devecchi, and M. Volonteri, Astrophys. J 694, 302 (2009)

- (43) M. Volonteri, Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 18, 279-315 (2010) [arXiv:1003.4404 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (44) B. Devecchi, M. Volonteri, E. M. Rossi, M. Colpi and S. Portegies Zwart, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 421, 1465 (2012) [arXiv:1201.3761 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (45) H. Katz, D. Sijacki and M.G. Haehnelt, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 451 (2015) 2352

- (46) Y. Sakurai, N. Yoshida, M. S. Fujii and S. Hirano, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 472, no.2, 1677-1684 (2017) [arXiv:1704.06130 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (47) N. C. Stone, A. H. W. Küpper and J. P. Ostriker, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 467, no.4, 4180-4199 (2017) [arXiv:1606.01909 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (48) B. Reinoso, D. R. G. Schleicher, M. Fellhauer, R. S. Klessen and T. C. N. Boekholt, Astron. Astrophys. 614, A14 (2018) [arXiv:1801.05891 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (49) H. Tagawa, Z. Haiman and B. Kocsis, [arXiv:1909.10517 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (50) T. C. N. Boekholt, D. R. G. Schleicher, M. Fellhauer, R. S. Klessen, B. Reinoso, A. M. Stutz and L. Haemmerle, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 476, no.1, 366-380 (2018) [arXiv:1801.05841 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (51) H. Yajima and S. Khochfar, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 457 2423 (2016)

- (52) M. B. Davies, M. C. Miller and J. M. Bellovary, Astrophys. J. Lett. 740, L42 (2011) [arXiv:1106.5943 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (53) A. Lupi, F. Haardt, M. Dotti, D. Fiacconi, L. Mayer and P. Madau, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 456, no.3, 2993-3003 (2016) [arXiv:1512.02651 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (54) M. Kawasaki, A. Kusenko and T. T. Yanagida, Phys. Lett. B 711, 1-5 (2012) [arXiv:1202.3848 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (55) K. Kohri, T. Nakama and T. Suyama, Phys. Rev. D 90, no.8, 083514 (2014) [arXiv:1405.5999 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (56) T. Nakama, T. Suyama and J. Yokoyama, Phys. Rev. D 94, no.10, 103522 (2016) [arXiv:1609.02245 [gr-qc]].

- (57) P. D. Serpico, V. Poulin, D. Inman and K. Kohri, Phys. Rev. Res. 2, no.2, 023204 (2020) [arXiv:2002.10771 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (58) C. Ünal, E. D. Kovetz and S. P. Patil, Phys. Rev. D 103, no.6, 063519 (2021) [arXiv:2008.11184 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (59) B. J. Carr, K. Kohri, Y. Sendouda and J. Yokoyama, Phys. Rev. D 81, 104019 (2010) [arXiv:0912.5297 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (60) B. J. Carr, K. Kohri, Y. Sendouda and J. Yokoyama, [arXiv:2002.12778 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (61) A. M. Green and B. J. Kavanagh, J. Phys. G 48, no.4, 043001 (2021) [arXiv:2007.10722 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (62) B. J. Carr and F. Kuhnel, [arXiv:2110.02821 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (63) K. Watarai, J. Fukue, M. Takeuchi, S. Mineshige, Publ. Astron. Soc. Jap. 52, 133 (2000)

- (64) K. y. Watarai and S. Mineshige, Astrophys. J. 596, 421-429 (2003) [arXiv:astro-ph/0306548 [astro-ph]].

- (65) F. Yuan and R. Narayan, Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 52, 529-588 (2014) [arXiv:1401.0586 [astro-ph.HE]].

- (66) K. Kohri and S. Mineshige, Astrophys. J. 577, 311-321 (2002) [arXiv:astro-ph/0203177 [astro-ph]].

- (67) K. Kohri, R. Narayan and T. Piran, Astrophys. J. 629, 341-361 (2005) [arXiv:astro-ph/0502470 [astro-ph]].

- (68) M. C. Begelman, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 184, 53 (1978)

- (69) A. Sadowski, Astrophys. J. Suppl. 183, 171-178 (2009) [arXiv:0906.0355 [astro-ph.HE]].

- (70) J. S. B. Wyithe and A. Loeb, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 425, 2892 (2012)

- (71) P. Madau, F. Haardt and M. Dotti, Astrophys. J. Lett. 784, L38 (2014) [arXiv:1402.6995 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (72) K. Inayoshi, Z. Haiman and J. P. Ostriker, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 459, no.4, 3738-3755 (2016) [arXiv:1511.02116 [astro-ph.HE]].

- (73) E. Pezzulli, R. Valiante, and R. Schneider Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 458, 3047 (2016)

- (74) E. Pezzulli, M. Volonteri, R. Schneider and R. Valiante, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 471, no.1, 589-595 (2017) [arXiv:1706.06592 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (75) M. C. Begelman and M. Volonteri, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 464, 1102 (2017) [arXiv:1609.07137 [astro-ph.HE]].

- (76) T. Alexander and P. Natarajan, Science 345 (2014) 1330.

- (77) F. Pacucci, P. Natarajan, M. Volonteri, N. Cappelluti and C. M. Urry, Astrophys. J. Lett. 850, no.2, L42 (2017) [arXiv:1710.09375 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (78) E. Takeo, K. Inayoshi and S. Mineshige, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 497, no.1, 302-317 (2020) [arXiv:2002.07187 [astro-ph.HE]].

- (79) P. Natarajan, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 501, 1413 (2021)

- (80) T. Ebisuzaki, J. Makino, T. G. Tsuru, Y. Funato, S. F. Portegies Zwart, P. Hut, S. McMillan, S. Matsushita, H. Matsumoto and R. Kawabe, Astrophys. J. Lett. 562, L19 (2001) [arXiv:astro-ph/0106252 [astro-ph]].

- (81) T. L. Tanaka, R. M. O’Leary and R. Perna, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 455, no.3, 2619-2626 (2016) [arXiv:1509.05406 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (82) A. Ewall-Wice, T. C. Chang, J. Lazio, O. Dore, M. Seiffert and R. A. Monsalve, Astrophys. J. 868, no.1, 63 (2018) [arXiv:1803.01815 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (83) S. Sazonov and I. Khabibullin, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 489, no.1, 1127-1138 (2019) [arXiv:1812.05527 [astro-ph.HE]].

- (84) A. Ewall-Wice, T. C. Chang and T. J. W. Lazio, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 492, no.4, 6086-6104 (2020) [arXiv:1903.06788 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (85) Q. B. Ma, B. Ciardi, M. B. Eide, P. Busch, Y. Mao and Q. J. Zhi, Astrophys. J. 912, no.2, 143 (2021) [arXiv:2103.09394 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (86) J. D. Bowman, A. E. E. Rogers, R. A. Monsalve, T. J. Mozdzen and N. Mahesh, Nature 555, no.7694, 67-70 (2018) [arXiv:1810.05912 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (87) G. D’Amico, P. Panci and A. Strumia, Phys. Rev. Lett. 121 (2018) no.1, 011103 doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.011103 [arXiv:1803.03629 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (88) N. Hiroshima, K. Kohri, T. Sekiguchi and R. Takahashi, Phys. Rev. D 104, no.8, 083547 (2021) [arXiv:2103.14810 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (89) P. J. E. Peebles, Astrophys. J. 153, 1 (1968)

- (90) Y. B. Zeldovich, V. G. Kurt and R. A. Sunyaev, Sov. Phys. JETP 28, 146 (1969) [Zh.Eksp.Teor.Fiz. 55 (1968) 278-286]

- (91) S. Seager, D. D. Sasselov and D. Scott, Astrophys. J. Suppl. 128, 407-430 (2000) [arXiv:astro-ph/9912182 [astro-ph]].

- (92) Y. Ali-Haimoud and C. M. Hirata, Phys. Rev. D 83, 043513 (2011) [arXiv:1011.3758 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (93) J. Chluba and R. M. Thomas, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 412, 748 (2011) [arXiv:1010.3631 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (94) H. Liu, T. R. Slatyer and J. Zavala, Phys. Rev. D 94, no.6, 063507 (2016) [arXiv:1604.02457 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (95) H. Liu, G. W. Ridgway and T. R. Slatyer, Phys. Rev. D 101, no.2, 023530 (2020) [arXiv:1904.09296 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (96) T. R. Slatyer, Phys. Rev. D 93, no.2, 023527 (2016) [arXiv:1506.03811 [hep-ph]].

- (97) T. R. Slatyer, Phys. Rev. D 93, no.2, 023521 (2016) [arXiv:1506.03812 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (98) S. Kato, J. Fukue and S. Mineshige, “Black-Hole Accretion Disks — Towards a New Paradigm”, ISBN 978-4-87698-740-5, Kyoto University Press (Kyoto, Japan), 2008,

- (99) N. Kawanaka and S. Mineshige, Publ. Astron. Soc. Jap. 73, 630 (2021) [arXiv:2012.05386 [astro-ph.HE]].

- (100) V.A. Moss, J.R. Allison, E.M. Sadler, R. Urquhart, R. Soria, J.R. Callingham, S.J. Curran, et al, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 471, 2952-2973 (2017), [arXiv:1707.01542 [astro-ph.GA]]

- (101) F. Ursini, L. Bassani, F. Panessa, A. Bazzano, A. J. Bird, A. Malizia and P. Ubertini, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 474, no.4, 5684-5693 (2018) [arXiv:1712.01300 [astro-ph.HE]].

- (102) S. J. Curran and S. W. Duchesne, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 476, no.d34, 5580-3590 (2018) [arXiv:1802.05760 [astro-ph.GA]]

- (103) R. C. Hickox and D. M. Alexander, Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 56, 625-671 (2018) [arXiv:1806.04680 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (104) R. Morganti and T. Oosterloo, Astron. Astrophys. Review 26, 4 (2018) [arXiv:1807.01475 [astro-ph.GA]]

- (105) H. Liszt, Astrophys. J. Lett. 908, L127 (2020) [arXiv:2012.04702 [astro-ph.GA]]

- (106) C. J. Willott, L. Albert, D. Arzoumanian, J. Bergeron, D. Crampton, P. Delorme, J.B. Hutchings, A. Omont, C. Reyle, and D. Schade, Astrophys. J. 140, 546 (2010) [arXiv:1006.1342 [astro-ph.CO]]

- (107) J. M. Shull, and M. E. van Steenberg, Astrophys. J. 298, 268 (1985).

- (108) X. L. Chen and M. Kamionkowski, Phys. Rev. D 70, 043502 (2004) [arXiv:astro-ph/0310473 [astro-ph]].

- (109) E. Ripamonti, M. Mapelli and A. Ferrara, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 374, 1067-1077 (2007) [arXiv:astro-ph/0606482 [astro-ph]].

- (110) N. Padmanabhan and D. P. Finkbeiner, Phys. Rev. D 72, 023508 (2005) [arXiv:astro-ph/0503486 [astro-ph]].

- (111) T. Kanzaki and M. Kawasaki, Phys. Rev. D 78, 103004 (2008) [arXiv:0805.3969 [astro-ph]].

- (112) T. R. Slatyer, N. Padmanabhan and D. P. Finkbeiner, Phys. Rev. D 80, 043526 (2009) [arXiv:0906.1197 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (113) T. Kanzaki, M. Kawasaki and K. Nakayama, Prog. Theor. Phys. 123, 853-865 (2010) [arXiv:0907.3985 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (114) C. Evoli, M. Valdes, A. Ferrara and N. Yoshida, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 422, 420-433 (2012)

- (115) V. Poulin, J. Lesgourgues and P. D. Serpico, JCAP 03, 043 (2017) [arXiv:1610.10051 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (116) O. Mena, S. Palomares-Ruiz, P. Villanueva-Domingo and S. J. Witte, Phys. Rev. D 100, no.4, 043540 (2019) [arXiv:1906.07735 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (117) H. Liu, W. Qin, G. W. Ridgway and T. R. Slatyer, [arXiv:2008.01084 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (118) B. Bolliet, J. Chluba and R. Battye, [arXiv:2012.07292 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (119) F. Sassano, R. Schneider, R. Valiante, K. Inayoshi, S. Chon, K. Omukai, L. Mayer and P. R. Capelo, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 506, no.1, 613-632 (2021) [arXiv:2106.08330 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (120) F. Pacucci and A. Loeb, [arXiv:2110.10176 [astro-ph.GA]].

- (121) S. Furlanetto, S. P. Oh and F. Briggs, Phys. Rept. 433, 181-301 (2006) [arXiv:astro-ph/0608032 [astro-ph]].

- (122) H. Liu and T. R. Slatyer, Phys. Rev. D 98, no.2, 023501 (2018) [arXiv:1803.09739 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (123) R. Basu, S. Banerjee, M. Pandey and D. Majumdar, [arXiv:2010.11007 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (124) S. A. Wouthuysen, Astron. J. 57 31–32 (1952).

- (125) G. B. Field, Astrophys. J. 129 536 (1959).

- (126) S. Singh, J. N. T., R. Subrahmanyan, N. U. Shankar, B. S. Girish, A. Raghunathan, R. Somashekar, K. S. Srivani and M. S. Rao, [arXiv:2112.06778 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (127) A. K. Saha and R. Laha, [arXiv:2112.10794 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (128) Z. Abdurashidova et al. [HERA], [arXiv:2108.02263 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (129) V. Bromm, Rept. Prog. Phys. 76, 112901 (2013) [arXiv:1305.5178 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (130) J. O. Gong and N. Kitajima, JCAP 08, 017 (2017) [arXiv:1704.04132 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (131) J. O. Gong and N. Kitajima, JCAP 11, 041 (2018) [arXiv:1803.02745 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (132) A. Hektor, G. Hütsi, L. Marzola, M. Raidal, V. Vaskonen and H. Veermäe, Phys. Rev. D 98, no.2, 023503 (2018) [arXiv:1803.09697 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (133) G. Hütsi, M. Raidal and H. Veermäe, Phys. Rev. D 100, no.8, 083016 (2019) [arXiv:1907.06533 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (134) G. Hasinger, JCAP 07, 022 (2020) [arXiv:2003.05150 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (135) P. Villanueva-Domingo and K. Ichiki, [arXiv:2104.10695 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (136) Y. Yang, Phys. Rev. D 104, no.6, 063528 (2021) [arXiv:2108.11130 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (137) Y. Yang, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 508, 5709 (2021) [arXiv:2110.06447 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (138) S. K. Acharya, J. Dhandha and J. Chluba, [arXiv:2208.03816 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (139) K. J. Mack and D. H. Wesley, [arXiv:0805.1531 [astro-ph]].

- (140) S. Clark, B. Dutta, Y. Gao, Y. Z. Ma and L. E. Strigari, Phys. Rev. D 98, no.4, 043006 (2018) [arXiv:1803.09390 [astro-ph.HE]].

- (141) A. Halder and M. Pandey, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 508, 3446 (2021) [arXiv:2101.05228 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (142) P. K. Natwariya, A. C. Nayak and T. Srivastava, [arXiv:2107.12358 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (143) S. Mittal, A. Ray, G. Kulkarni and B. Dasgupta, [arXiv:2107.02190 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (144) J. Cang, Y. Gao and Y. Z. Ma, [arXiv:2108.13256 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (145) A. P. Beardsley, M. F. Morales, A. Lidz, M. Malloy and P. M. Sutter, Astrophys. J. 800, no.2, 128 (2015) [arXiv:1410.5427 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (146) https://www.skatelescope.org

- (147) M. Tegmark and M. Zaldarriaga, Phys. Rev. D 82 (2010) 103501 [arXiv:0909.0001].

- (148) J. Burns, S. Bale, R. Bradley, Z. Ahmed, S. W. Allen, J. Bowman, S. Furlanetto, R. MacDowall, J. Mirocha and B. Nhan, et al. [arXiv:2103.05085 [astro-ph.CO]].