Dimer-dimer collisions at finite energies in two-component Fermi gases

Abstract

We introduce a major theoretical generalization of existing techniques for handling the three-body problem that accurately describes the interactions among four fermionic atoms. Application to a two-component Fermi gas accurately determines dimer-dimer scattering parameters at finite energies and can give deeper insight into the corresponding many-body phenomena. To account for finite temperature effects, we calculate the energy-dependent complex dimer-dimer scattering length, which includes contributions from elastic and inelastic collisions. Our results indicate that strong finite-energy effects and dimer dissociation are crucial for understanding the physics in the strongly interacting regime for typical experimental conditions. While our results for dimer-dimer relaxation are consistent with experiment, they confirm only partially a previously published theoretical result.

pacs:

31.15.xj,34.50.-s,34.50Cx,67.85.-dThe physics of strongly interacting fermionic systems is of fundamental importance in many areas of physics encompassing condensed matter physics, nuclear physics, particle physics and astrophysics. The last few years have seen extensive theoretical and experimental efforts devoted to the field of ultracold atomic Fermi gases. The ability to control interatomic interactions through magnetically tunable Feshbach resonances has opened up broad vistas of experimentally accessible phenomena, providing a quantum playground for studying the strongly interacting regime. For instance, near a Feshbach resonance between two dissimilar fermions, the -wave scattering length can assume positive and negative values, allowing for the systematic exploration of Bose-Einstein condensation (BEC) and the Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) crossover regime, in which bosonic () and fermionic () types of superfluidity connect smoothly CrossOverTheory ; CrossOverExp . In this broad context, few-body correlations Strinati ; Petrov play an important role in describing the dynamics of such systems. On the BEC side of the resonance (), dissimilar fermions pair-up into weakly-bound bosonic dimers, and the zero (collision) energy dimer-dimer scattering length, , determines various experimental observables such as the molecular gas collective modes, the internal energy, and even the macroscopic spatial extent of the confined cloud CrossOverTheory ; CrossOverExp . Although a better description of the many-body behavior has emerged through the inclusion of few-body correlations, most of the current understanding of crossover physics relies on zero-energy theories, and very little is known about finite energy effects in this regime (see Ref. FiniteTemp and references therein).

In this Letter we demonstrate important finite energy effects which can potentially impact the physics of a finite temperature ultracold Fermi gas in the crossover regime. Our results show deviations from zero-energy dimer-dimer collisions and indicate that, at experimentally relevant temperatures and scattering lengths, molecular dissociation might play an important role. The crossover regime can be viewed as a long-lived atom-molecule mixture, where dimers are dynamically converted to atoms and vice-versa. In order to account for finite temperature effects, we calculate the energy dependent complex dimer-dimer scattering length, , where is the collision energy. The real and imaginary parts of correspond, respectively, to contributions from elastic and inelastic (dissociative) collisions ComplexScatLen , both of which should be considered to properly model the Fermi gas at realistic temperatures. In the zero-energy limit we reproduce the well known prediction Petrov . However, when the dimer binding energy, (where is the two-body reduced mass) is comparable to the gas temperature , finite energy effects and molecular dissociation become important, defining a critical scattering length , where is Boltzmann’s constant, beyond which an atom-molecule mixture should prevail.

We also study dimer-dimer relaxation, in which two weakly-bound dimers collide and make an inelastic transition to a lower energy state. In such a process, the kinetic energy released is enough for the collision partners to escape from typical traps. Ref. Petrov predicted that, near a Feshbach resonance, dimer-dimer relaxation is suppressed as , explaining the long lifetimes observed in several experiments CrossOverExp ; LongLivedMol . Here we also verify this suppression, although with an dependence that is not described as a simple power-law scaling as originally predicted Petrov . While the scaling law has already been tested (Regal et al. LongLivedMol found and Bourdel et al. CrossOverExp ), our calculations demonstrate that finite range corrections can explain the apparent experimental scaling law behavior, despite deviations from that power-law for larger .

We solve the four-body Schrödinger equation in the hyperspherical adiabatic representation, which offers a simple yet quantitative picture. A finite range model is assumed for the interatomic interaction, and a physically-motivated variational basis set is adopted to solve the hyperangular equations FourBodyUs . While several hyperangular parameterizations exist, we find that the best choice is the “democratic” hyperspherical coordinates HypCoord in which all possible fragmentation channels are treated on an equal footing, which describes elastic and inelastic processes in an unified picture.

In the adiabatic hyperspherical representation, the collective motion of the four fermions is described in terms of the hyperradius , characterizing the overall size of the system. The interparticle relative motion is described by the hyperangles , and the set of Euler angles , , specifying the orientation of the body-fixed frame HypCoord . and parameterize the moments of inertia while , and parameterize internal configurations HypCoord . Integrating out the hyperangular degrees of freedom, the Schrödinger equation reduces to a system of coupled ordinary differential equations, given in atomic units (used throughout this Letter) by:

| (1) |

where is the four-body reduced mass ( being the atomic mass), is the total energy, is the hyperradial wavefunction, and represents all quantum numbers needed to label each channel. Scattering observables can then be extracted by solving Eq. (1), where the nonadiabatic couplings drive inelastic transitions between channels described by the effective potentials .

In the hyperspherical representation, the major reduction to Eq. (1) is accomplished by finding eigenfunctions of the (fixed ) adiabatic Hamiltonian,

| (2) |

In the above equation, is the grand angular momentum operator HypCoord and includes all two-body interactions Euler . For simplicity, we neglect the interaction between identical fermions and assume the one between dissimilar fermions to be , where is the interatomic distance and is tuned to produce the desired . We choose the atomic mass and effective range a.u. Flambaum to be those of 40K. The eigenvalues and eigenfunctions of , namely the hyperspherical potentials and channel functions , determine the effective potentials and nonadiabatic couplings in Eq. (1): and , where and . We find variationally by expanding in exact eigenfunctions of Eq. (2) at large and small FourBodyUs . At ultracold energies the convergence of the scattering observables with respect to the number of basis functions is surprisingly fast FourBodyUs .

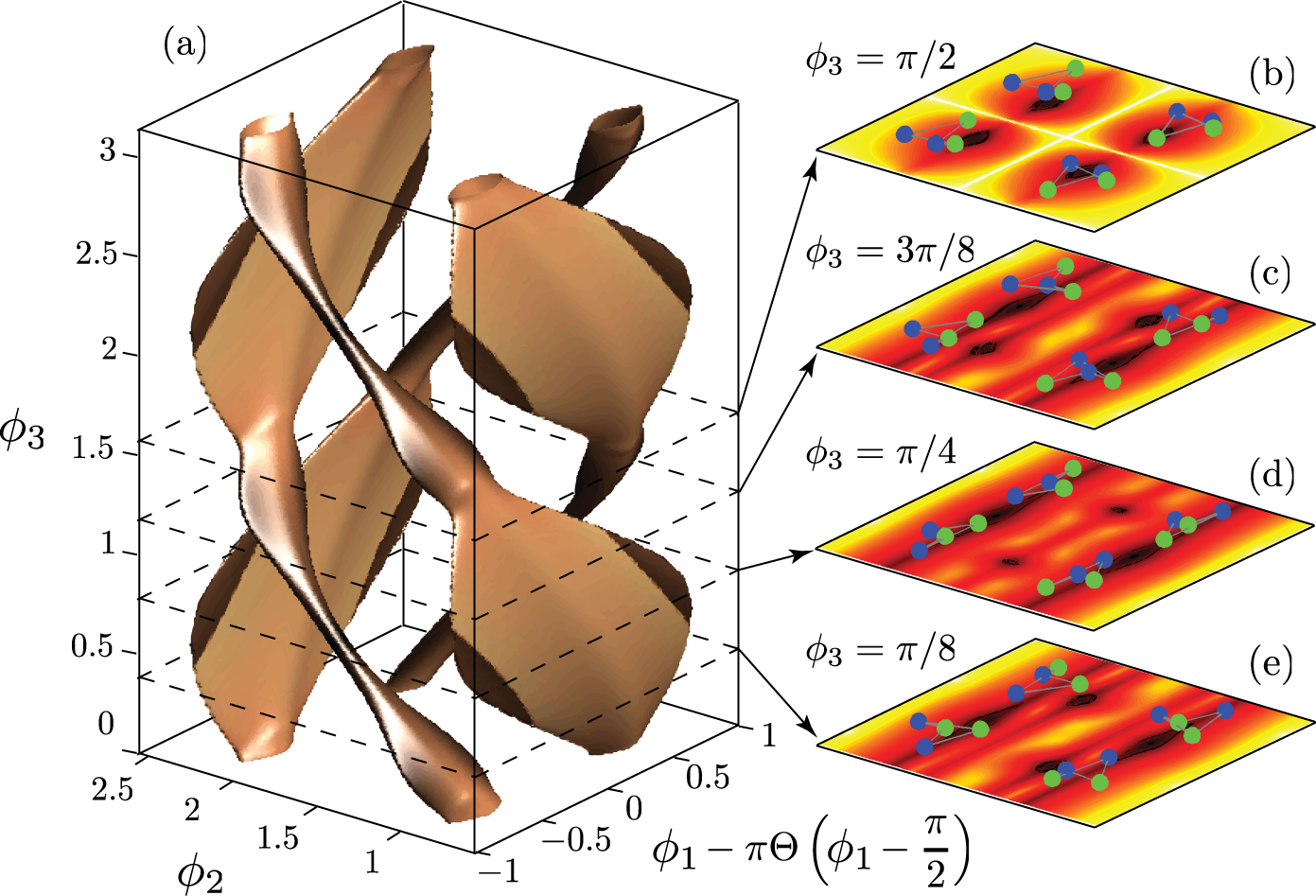

However, including higher order correlations that describe dimer-atom-atom and four free atom configurations is crucial for accurately describing scattering processes at any collision energy. We find that for the strongest contribution to the probability density of the dimer-dimer channel function comes from dimer-atom-atom like configurations. Figure 1 shows a graphical representation of this channel function in terms of the internal configuration angles , and . The four “cobra”-like surfaces explicitly illustrate the four-fold symmetry () of the fermionic problem. The “spines” of the cobras correspond to the interaction valleys where two dissimilar fermions are in close proximity while the “hoods” loosely represent the larger phase-space explored by dimer-atom-atom like configurations.

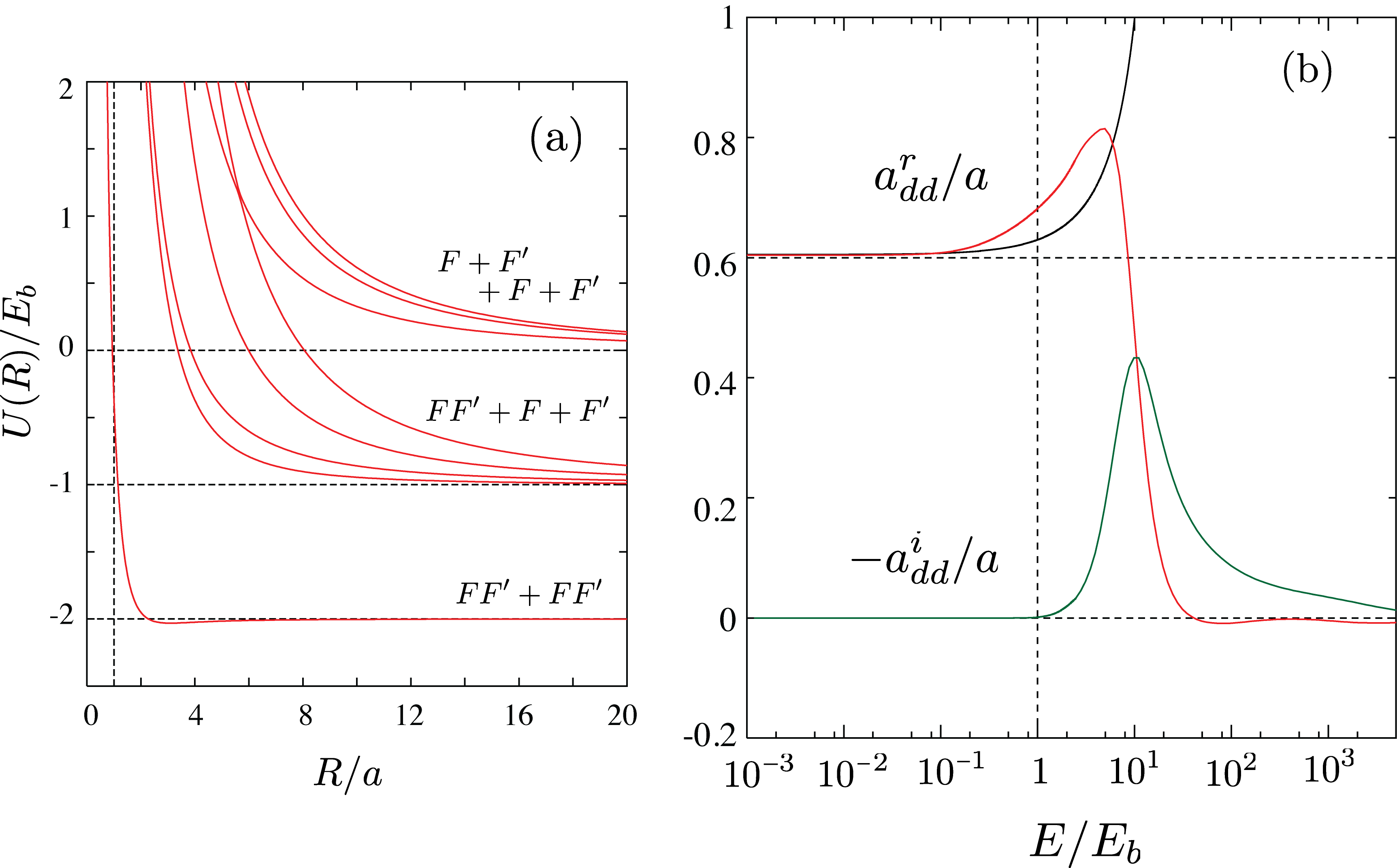

Figure 2(a) shows the hyperspherical potentials for showing the full energy landscape with the four-body thresholds for dimer-dimer (), dimer-atom-atom (), and four atom () collisions. Notice that the four-body potential associated with dimer-dimer collisions is repulsive for , indicating that zero-energy dimer-dimer elastic scattering must be qualitatively similar to scattering by a hard-sphere of radius , i.e., . Although a clear and qualitative picture emerges from the four-body potentials alone, we in practice extract scattering observables from coupled-channel solutions to Eq. (1). We define the energy dependent dimer-dimer scattering length, , in terms of the complex phase-shift obtained from the corresponding -matrix element [],

| (3) |

Here, , is the collision energy and and are the real and imaginary parts of , representing elastic and inelastic contributions ComplexScatLen .

Figure 2(b) shows and for . For energies we find that in agreement with Refs. Petrov ; Javier while for , although molecular dissociation is still not allowed, i.e. , we obtain strong corrections to the zero-energy result. At these energies, an effective range expansion, where Javier , is accurate over a small range, but quickly fails to reproduce our results [see black solid line in Fig. 2(b)]. For , the channels for molecular dissociation become open leading to strong inelastic contributions to , as parametrized by . Our results indicate that both and are universal functions of energy and scattering length, i.e., insensitive to the details of the short-range physics, which should extend up to in the absence of deeply bound states. Due to the small number of basis functions used in these calculations, our results for are not fully converged, but we expect their qualitative behavior, i.e., the sharp decease in , to persist.

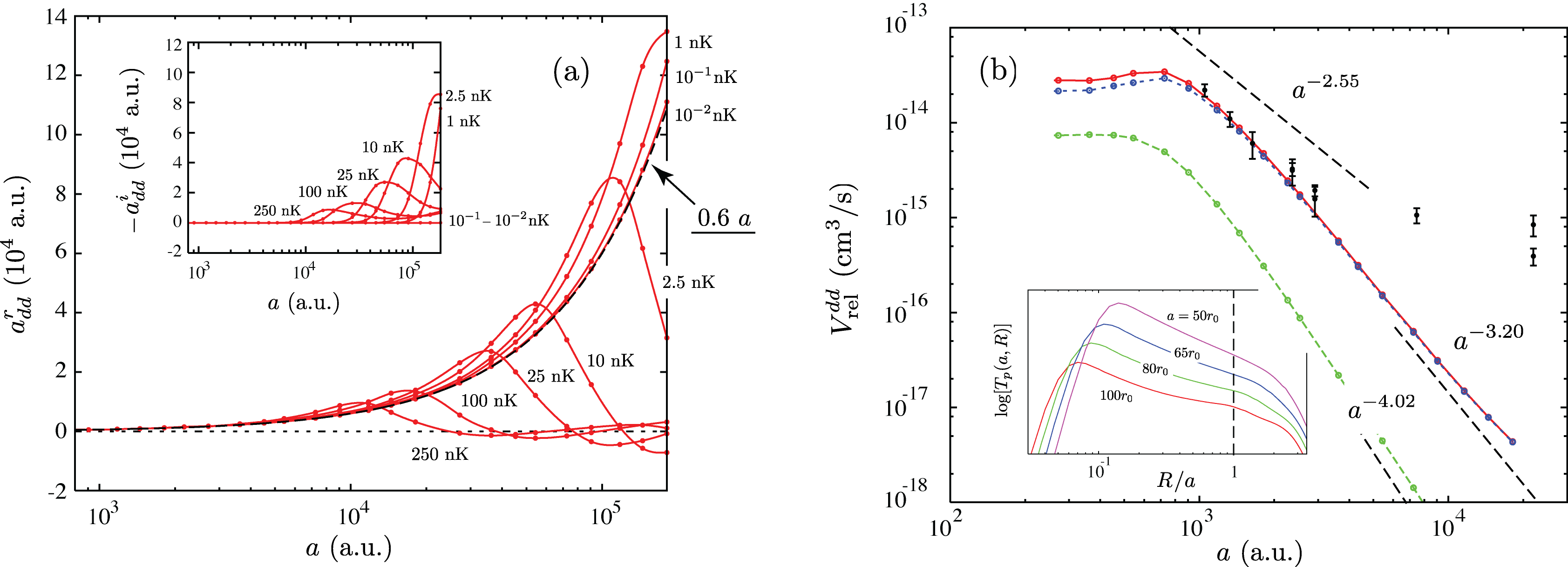

Figure 3(a) demonstrates that when approaching the Feshbach resonance () at any finite collision energy, molecular dissociation becomes increasingly more important and substantially deviates from the zero-energy predictions [black dashed line and inset in Fig. 3(a)]. As , becomes extremely small and such finite energy effects [see Fig. 2(b)] are relevant even at ultracold energies. Therefore, the molecular binding energy , or equivalently , defines the range beyond which (i.e., ) deviations from the zero-energy predictions can be observed. Perhaps more importantly, it specifies a regime beyond which molecular dissociation can lead to a long-lived atom-molecule mixture AtomMoleculeMixture ; AtomMoleculeMixtureAdd , where dimers are continuously converted to atoms and vice-versa, i.e. . Further, this indicates that the underlying physics of the strongly interacting regime may fundamentally depend on temperature. Values for at 100 nK are 7000 a.u. for 40K and 17000 a.u. for 6Li, and therefore the finite energy effects above can become experimentally relevant CrossOverExp .

We also study vibrational relaxation due to dimer-dimer collisions. We verify the suppression of the relaxation rate as , however, with a different dependence than predicted in Ref. Petrov . In Ref. Petrov it was assumed that the main decay pathway for relaxations is a purely three-body process and requires only three atoms to be enclosed at short distances. Therefore, it neglects the effects of the interaction with the fourth atom. Here, however, we analyze such effects and find that it strongly influences the suppression of relaxation. In our calculations we express the inelastic transitions probability in terms of the probability of having three atoms at short distances as a function of the distance of the fourth atom from the collision center EPAPS . We calculate from our fully coupled-channel solutions and effective potentials [see Figs. 1 and 2(a)] and our results are shown in the inset of Fig. 3(b).

In our model the relaxation rate is simply proportional to the transition probability . It is interesting note that our formulation allows for the analysis of different decay pathways. For instance, at short distances, , describes inelastic transitions in which all four atoms are involved in the collision process. At large distances, , describes the decay pathway where only three atoms participate in the collision, akin to the process studied in Ref. Petrov . We note, however, that for values of up to the scaling law for relaxation depends strongly on and greatly deviate from the scaling. In order to take into account inelastic processes for all values of we define an effective transition probability by integrating over EPAPS . Our results for the relaxation rate, , are shown in Fig. 3(b) where the red solid line is obtained by integrating from up to MyComment giving an apparent scaling law of . The dashed lines are obtained from integrating from to and from to , which yields scaling laws of and , respectively, “separating” the contributions from the decay pathways in which four and three atoms participate in the collision process. The amplitudes for each of these contributions, however, are disconnected as they depend on the details of the four- and three-body short-range physics. In contrast, the amplitudes for the and processes are governed by the same three-body physics. As a result, the fact that we don’t observe the scaling implies that it is not important for the range of used here. The amplitude for the process which leads to the scaling is exponentially suppressed owing to the unfavorable overlap of the dimers’ wavefunction [see inset of Fig. 3(b)]. In fact, for our largest values of , it is already apparent that in the very large limit the rate deviates from , however, to a behavior different than EPAPS .

Figure 3(b) rescales our results for by an overall constant chosen to fit the experimental data for 40K at a temperature of nK (Regal et al. LongLivedMol ). We note, however, that between and a.u. Comment , our results agree with both the experimental data and the scaling law, approaching our predicted scaling law only for larger values of . This change in behavior of originates in the finite range of our model, which represents physics beyond the zero-range model of Ref. Petrov where the scaling applies for all .

In summary, we have calculated the energy dependent complex dimer-dimer scattering length, , by solving the four-body Schrödinger equation in the adiabatic hyperspherical representation. Our results demonstrate that for experimentally relevant temperatures and scattering lengths the elastic and inelastic contributions of are equally important. We show that molecular dissociation plays an important role and suggest that the many-body behavior in the strongly interacting regime might be significantly altered at finite temperature. Our results also demonstrate a stronger suppression for dimer-dimer relaxation, compared to that obtained in Ref. Petrov , while remaining consistent with experimental data.

The authors would like to acknowledge D. S. Jin’s group for providing their experimental data, J. von Stecher and D. S. Petrov for fruitful discussions, and the W. M. Keck Foundation for providing computational resources. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation.

References

- (1) D. M. Eagles, Phys. Rev. 186, 456 (1969); A. J. Leggett, J. Phys. C 41, 7 (1980); M. Holland et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 120406 (2001); E. Timmermans et al., Phys. Lett. A 285, 228 (2001); Y. Ohashi and A. Griffin, Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 130402 (2002).

- (2) C. Chin et al., Science 305, 1128 (2004); T. Bourdel et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 050401 (2004); M. Bartenstein et al., ibid. 92, 120401 (2004); C. A. Regal, M. Greiner, and D. S. Jin, ibid. 92, 040403 (2004); M. W. Zwierlein et al., ibid. 92, 120403 (2004); G. B. Partridge et al., ibid. 95 020404 (2005); M. Bartenstein et al., ibid. 92, 203201 (2004); J. Kinast et al., ibid. 92, 150402 (2004). M. Greiner, C. A. Regal, and D. S. Jin, ibid. 94, 070403 (2005); M. W. Zwierlein, et al., Nature (London) 435, 1047 (2005).

- (3) P. Pieri and G. C. Strinati, Phys. Rev. B 61, 15370 (2000).

- (4) D. S. Petrov, C. Salomon, and G. V. Shlyapnikov, Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 090404 (2004); Phys. Rev. A 71, 012708 (2005).

- (5) M. J. Wright et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 150403 (2007).

- (6) J. L. Bohn and P. S. Julienne, Phys. Rev. A 56, 1486 (1997); R. C. Forrey et al., ibid. 58, R2645 (1998).

- (7) J. Cubizolles et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 240401 (2003); K. E. Strecker, G. B. Partridge, and R. G. Hulet, ibid. 91 080406 (2003); C. A. Regal, M. Greiner, and D. S. Jin, ibid. 92, 083201 (2004).

- (8) Nirav P. Mehta, Seth T. Rittenhouse, José P. D’Incao, Chris H. Greene, arXiv:0706.1296.

- (9) V. Aquilanti and S. Cavalli. J. Chem. Soc. : Faraday Transactions 95, 801 (1997); A. Kuppermann. J. Phys. Chem. A 101, 6368 (1997).

- (10) We omit all reference to the Euler angles because this study treats only the dominant partial wave , where is the total orbital angular momentum and is the parity quantum number.

- (11) V. V. Flambaum, G. F. Gribakin, and C. Harabati, Phys. Rev. A 59, 1998 (1999). The value for is obtained from the expression , Eq, (24), at resonance.

- (12) J. von Stecher, Chris H. Greene, and D. Blume, Phys. Rev. A 76, 053613 (2007); ibid. 77, 043619 (2008). in these works is calculated to an accuracy similar to our present value.

- (13) S. Jochim et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 240402 (2003).

- (14) Y. Shin, A. Schirotzek, C. H. Schunck, and W. Ketterle, Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 070404 (2008).

- (15) See Supplemental Material attached to this file for a more detailed description of our model for dimer-dimer relaxation.

- (16) We have found that integrating from up to is enough to ensure that contributions for and are neglegible.

- (17) The experimental data for a.u. were taken in the regime where the molecular size is expected to be larger than the interparticle spacing, which prohibits a proper comparisson to our results.