Do we expect to find the Super-Earths close to the gas giants?

Abstract

We have investigated the evolution of a pair of interacting planets embedded in a gaseous disc, considering the possibility of the resonant capture of a Super-Earth by a Jupiter mass gas giant. First, we have examined the situation where the Super-Earth is on the internal orbit and the gas giant on the external one. It has been found that the terrestrial planet is scattered from the disc or the gas giant captures the Super-Earth into an interior 3:2 or 4:3 mean-motion resonance. The stability of the latter configurations depends on the initial planet positions and on eccentricity evolution. The behaviour of the system is different if the Super-Earth is the external planet. We have found that instead of being captured in the mean-motion resonance, the terrestrial planet is trapped at the outer edge of the gap opened by the gas giant. This effect prevents the occurrence of the first order mean-motion commensurability. These results are particularly interesting in light of recent exoplanet discoveries and provide predictions of what will become observationally testable in the near future.

1 Introduction

So far we know only a few Super-Earths, i.e., planets less massive than . However, there is a good chance that in the near future, COROT and the Kepler mission will find more terrestrial type planets. An interesting possibility is the existence of Super-Earths close to Jupiter-like planets. Different mass objects embedded in a protoplanetary disc will migrate with different rates. The final configurations will depend on the intricate interplay among many physical processes including planet-planet, disc-planet and planet-star interactions. Here we focus on the possible resonant configurations of a gas giant and a Super-Earth orbiting a Solar-type star.

The early divergent conclusions concerned with the occurrence of terrestrial planets in hot Jupiter systems (Armitage, [2003], Raymond et al., [2005]) have been clarified by the most recent studies (Fogg & Nelson, [2007a], [2007b], Raymond et al., [2006]), which predict that terrestrial planets can grow and be retained in hot-Jupiter systems, both interior and exterior to the gas giant. Here we consider the evolution of an already formed Super-Earth and a gas giant, both embedded in a gaseous disc. In our studies we are interested in the possibility of the formation of resonant planetary configurations. First, we have examined the behaviour of the system when the terrestrial planet is on the internal orbit and the gas giant on the external one. Then we have reversed the situation such that the Jupiter is the internal planet and the Super-Earth is the external planet.

Two-dimensional hydrodynamical simulations have been employed in order to determine the occurrence of first-order mean-motion resonances as the outcome of convergent orbital migration. Our predictions have interesting astrobiological implications, which we discuss in the Conclusions section.

2 Results of the simulations

The evolution of the Super-Earth with a mass of 5.5 Earth masses and the Jupiter mass planet embedded in a gaseous disc has been calculated using the hydrodynamical code NIRVANA (details of the numerical scheme and code can be found in Nelson et al. ([2000])).

The surface density profile at the position of the planets is taken to be flat as in Papaloizou & Szuszkiewicz ([2005]). Our computational domain extends between 0.33 and 4 in units normalized in such a way that corresponds to the mean distance of the Jupiter from the Sun in the Solar System (5.2 AU). The disc is divided into grid-cells in the radial and azimuthal directions, respectively. The radial boundary conditions are taken to be open and the gravitational potential is softened with the softening parameter where denotes the disc semi-thickness.

2.1 The Super-Earth on the internal orbit

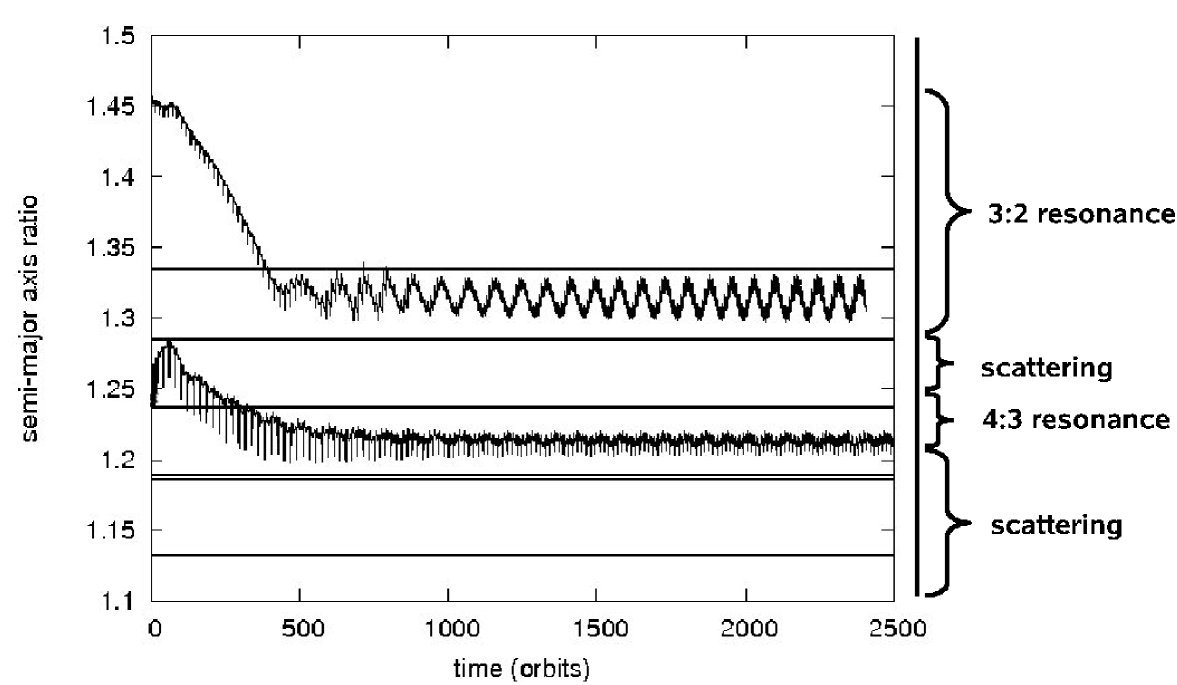

In this part we investigate the evolution of the Super-Earth on the internal orbit and the Jupiter on the external one. The planets are embedded in the flat part of the surface density profile and their relative separation varies in the range from 0.15 to 0.45. In order to get convergent migration of the planets we have performed the simulations with a constant aspect ratio =0.05, a constant kinematic viscosity , which at the initial interior planet’s radius corresponds to the viscosity parameter , and , which is two Jupiter masses spread out within the mean distance of the Jupiter from the Sun. For this set of disc parameters and masses of the planets the Jupiter migrates faster than the Super-Earth, and thus the planets approach each other. As the evolution proceeds two outcomes are possible, either the Super-Earth is ejected from the disc or it becomes locked in the 3:2 or 4:3 mean motion resonances (Podlewska & Szuszkiewicz, [2008]). The resonances located closer to the Jupiter such as 5:4 or 6:5 are not possible, because for such small separations the system becomes unstable and the Super-Earth is scattered from the disc. All the simulations are summarized in Fig. 1. Moreover, not all planetary pairs initially locked in a mean-motion resonance survived further evolution. In the case of 3:2 commensurability the libration width increases with time. In fact, in the case of relative separations 0.26 and 0.27, the amplitude of the oscillation grows and eventually the Super-Earth is scattered from the disc. The direct reason of this scattering is the excitation of the Super-Earth eccentricity.

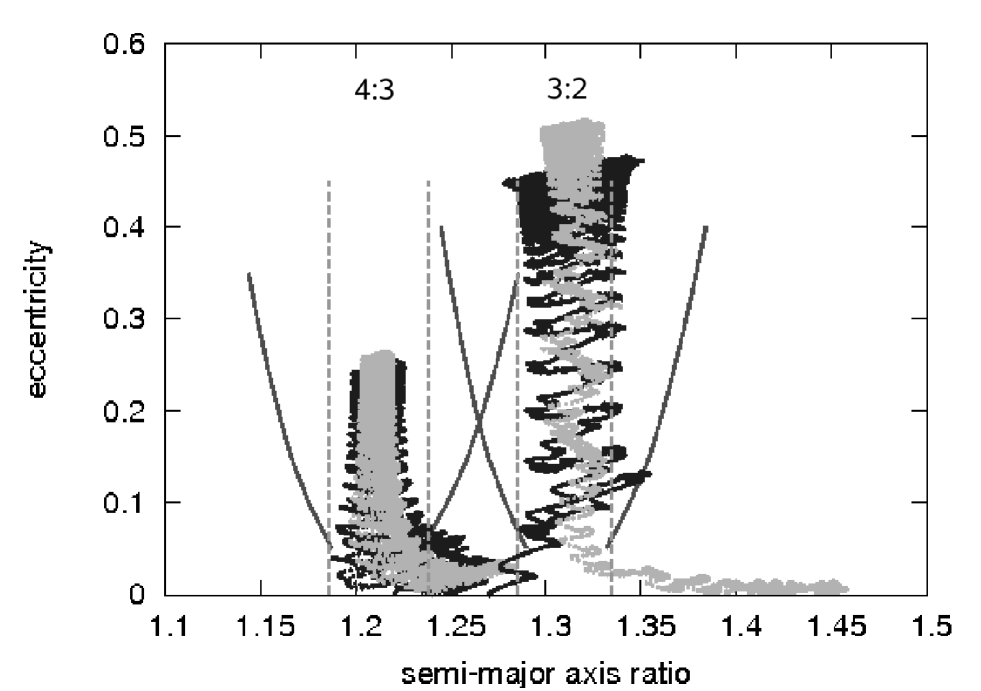

The eccentricity evolution of the terrestrial planets which survived in resonant configurations till the end of our calculations are shown in Fig.2. In this figure, we plot the eccentricity versus the semi-major axis ratio, which was calculated by dividing the semi-major axis of the Jupiter by the semi-major axis of the Super-Earth. For each commensurability the two solid lines show the maximum libration width obtained from the formula given by Winter & Murray ([1997]) in the pendulum approximation of the classical restricted three-body problem. The two dashed vertical lines in Fig. 2 denote the resonance width for the circular case. The eccentricity of the Super-Earth locked in 3:2 commensurability increases and at the end of simulations reaches a value of about 0.5. If the Super-Earth is locked in 4:3 mean motion resonance its eccentricity in all simulations approaches to a value around 0.3.

2.2 The Super-Earth on the external orbit

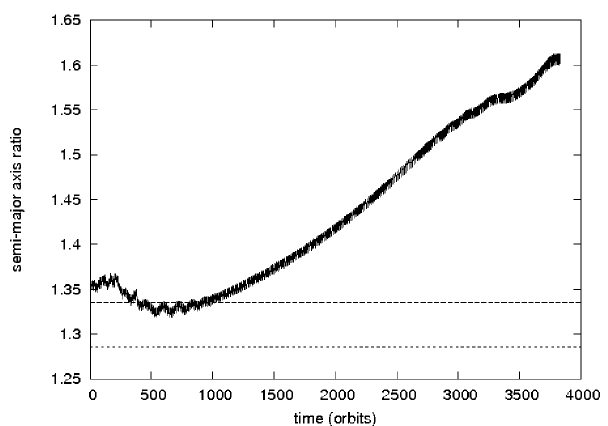

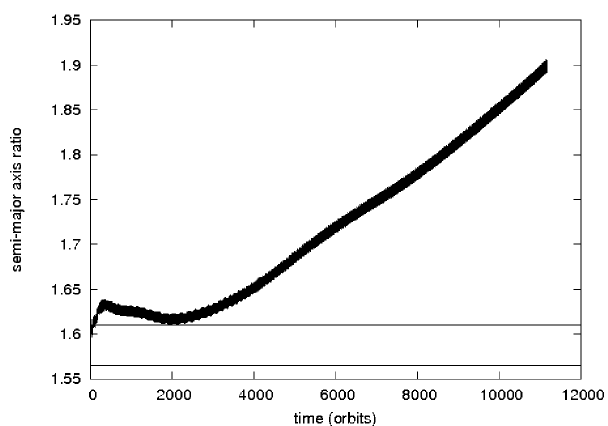

As we have shown in the previous section it is very likely that the Super-Earth on the internal orbit and the gas giant on the external one form a resonant configuration. Now we ask ourselves if the mean-motion commensurabilities can be established when the terrestrial planet is on the external orbit and the Jupiter is the internal planet. By changing the disc parameters we have succeeded in bringing the planets close to each other. Convergent migration has been achieved for the kinematic viscosity , the surface density and the aspect ratio . We have located the gas giant initially at distance 1 and the Super-Earth further from the star. In Fig. 3a (left panel) we show the evolution of the semi-major axis ratio of the planets for the initial separation 0.35. The horizontal lines show the width of the 2:3 resonance (Lecar et al., [2001]). However, the resonant configuration lasts just for a few hundred orbits and after that the relative distance between the planets increases. Before revealing the reason for which the 2:3 mean motion resonance cannot be sustained, let us check the possibility of the occurrence of the another first order commensurability, namely 1:2. To this aim, we have placed the Super-Earth further out from the Jupiter, at the relative separation 0.62. The evolution of this configuration is shown in Fig. 3b (right panel). The convergent migration continues for about 2000 orbits and after that, similarly to the previous case, the migration becomes divergent.

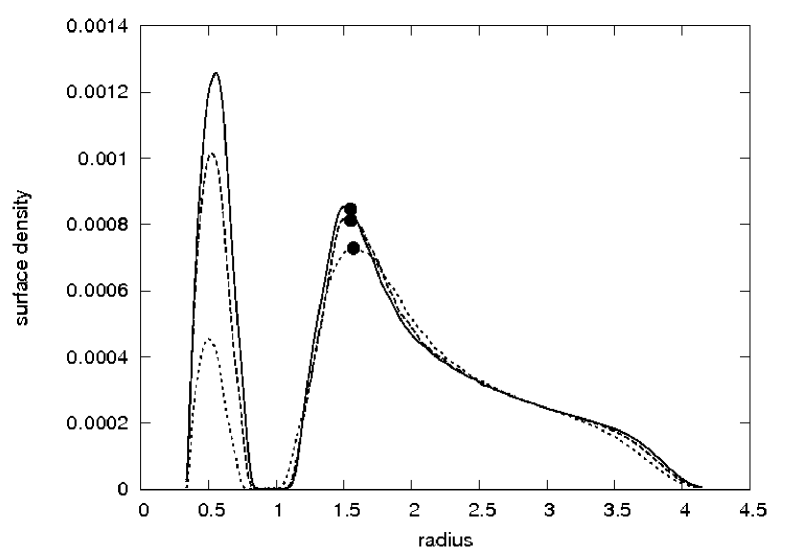

Mean-motion commensurability cannot be attained because the migration of the terrestrial planet is stopped at the outer edge of the gap and this is the reason for which the relative distance between the planets increases. The whole evolution can be described as follows. The Super-Earth embedded in the disc migrates inward toward the Jupiter according to type I migration until it reaches the outer edge of the gap, where it is trapped. This is illustrated in Fig. 4 where we show the surface density profile changes after about 2355, 3925 and 7850 orbits, together with the position of the terrestrial planet marked by the black dot. Once the terrestrial planet reaches the trap it remains captured till the end of the simulation. Such planetary trapping has been already noticed by Masset et al. ([2006]) and Pierens & Nelson ([2008]).

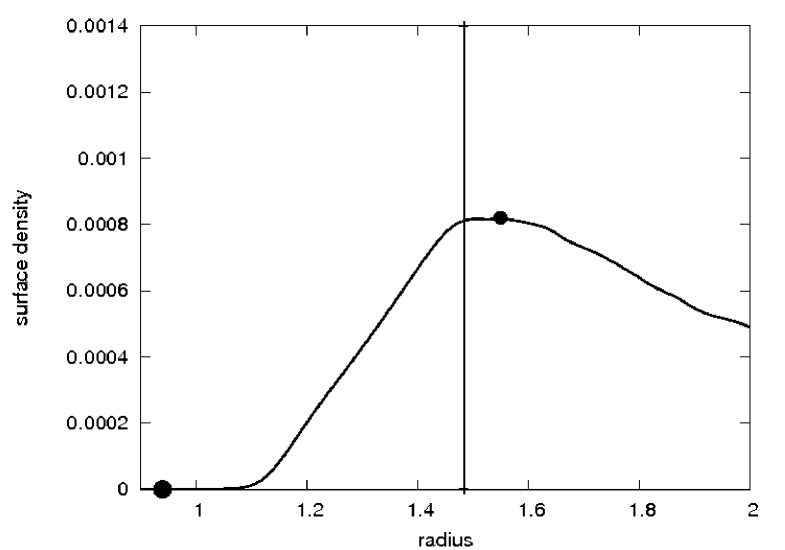

The conclusion is that first-order mean-motion commensurability cannot be achieved because the gap is very wide and the Super-Earth reaches the trap before it is captured in the resonance (Podlewska & Szuszkiewicz, [2009]). We have presented this in Fig. 5 where we plot the gap profile of the disc after 3925 orbits. The dots denote the position of the Super-Earth and the Jupiter. The vertical line shows the location of the 1:2 commensurability.

3 Conclusions

A large-scale orbital migration in young planetary systems might play an important role in shaping their architectures. Tidal gravitational forces are able to rearrange the planet positions according to their masses and the disc parameters. The final configuration after disc dispersal might be what we actually observe in the extrasolar systems. In particular, convergent migration can bring planets into mean-motion resonances as has been found in Podlewska & Szuszkiewicz ([2008]) in the case where the terrestrial planet is on the internal orbit.

When the Super-Earth is on the external orbit, it is captured at the outer edge of the gap opened by the gas giant (Podlewska & Szuszkiewicz, [2009]). Despite the absence of mean-motion resonance, the trapping at the outer edge of the gap can slow down the migration of the Super-Earth. Thus, depending on whether the Super-Earth is inside or outside the gas giant orbit, the most likely planet configurations will be different. We claim that the Super-Earth can survive in close proximity to the gas giant. The terrestrial planet is either locked in mean-motion commensurability or it is captured in the trap which prevents fast migration toward the star.

Our results have an interesting implication for astrobiological studies. Namely, if we have a gas giant in or near the habitable zone, then a terrestrial planet locked in the mean motion resonance or captured in the trap at the outer edge of the gap can be also located in the habitable zone. Some of the known extrasolar gas giants as well as the recently discovered Super-Earth in the Gliese 581 system (Udry et al., [2007]) are in the habitable zone. We can expect that future observations will reveal terrestrial planets close to gas giants.

4 Acknowledgments

This work has been partially supported by MNiSW grant N203 026 32/3831 (2007-2010) and MNiSW PMN grant - ASTROSIM-PL ”Computational Astrophysics. The formation and evolution of structures in the universe:from planets to galaxies” (2008-2010) The simulations reported here were performed using the Polish National Cluster of Linux Systems (CLUSTERIX) and the computational cluster ”HAL9000” of the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics at the University of Szczecin. I am grateful to Ewa Szuszkiewicz for enlightening discussions and suggestions and Adam Łacny for his helpful comments.

References

- [2003] Armitage, P., 2003, ApJ, 582, L47

- [2007a] Fogg, M. J., Nelson, R. P., 2007a, A&A, 461, 1195

- [2007b] Fogg, M. J., Nelson, R. P., 2007b, A&A, 472, 1003

- [2001] Lecar, M., Franklin, F. A., Holman, M. J., Murray, N. J., 2001, ARA&A 39, 581

- [2006] Masset, F. S., Morbidelli, A., Crida, A., Ferreira, J., 2006, ApJ, 642, 478

- [2000] Nelson R. P.et al. 2000, MNRAS, 318, 18

- [2005] Papaloizou, J. C. B., Szuszkiewicz, E., 2005, MNRAS, 363, 153

- [2008] Pierens, A., Nelson, R. P., 2008, A&A, 482, 333

- [2008] Podlewska, E., Szuszkiewicz, E., 2008, MNRAS, 386, 1347

- [2009] Podlewska, E., Szuszkiewicz, E., 2009, MNRAS, 397, 1995

- [2005] Raymond, S. N. et al. , 2005, Icarus, 177, 256

- [2006] Raymond, S. N., Mandell, A. M., Sigurdsson, S., 2006, Science, 313, 1413

- [2007] Udry, S. et al. , 2007, A&A, 469, L43

- [1997] Winter, O. C., Murray, C. D., 1997, A&A, 319, 290