Effects of quantum recoil forces in resistive switching in memristors

Abstract

Memristive devices, whose resistance can be controlled by applying a voltage and further retained, are attractive as possible circuit elements for neuromorphic computing. This new type of devices poses a number of both technological and theoretical challenges. Even the physics of the key process of resistive switching, usually associated with formation or breakage of conductive filaments in the memristor, is not completely understood yet. This work proposes a new resistive switching mechanism, which should be important in the thin-filament regime and take place due to the back reaction, or recoil, of quantum charge carriers—independently of the conventional electrostatically-driven ion migration. Since thinnest conductive filaments are in question, which are only several atoms thick and allow for a quasi-ballistic, quantized conductance, we use a mean-field theory and the framework of nonequilibrium Green’s functions to discuss the electron recoil effect for a quantum current through a nanofilament on its geometry and compare it with the transmission probability of charge carriers. Namely, we first study an analytically tractable toy model of a 1D atomic chain, to qualitatively demonstrate the importance of the charge-carrier recoil, and further proceed with a realistic molecular-dynamics simulation of the recoil-driven ion migration along a copper filament and the resulting resistive switching. The results obtained are expected to add to the understanding of resistive switching mechanisms at the nanoscale and to help downscale high-retention memristive devices.

pacs:

05.60.Gg, 73.63.-b, 73.63.Rt1. Introduction. Memristors—electric devices whose resistance “remembers” the history of the previously passed current Chua_Memristor —have attracted a lot of theoretical and experimental attention over the past decade, notably since the first working memristive device was manufactured in 2008 Memristor2008 . Memristors are particularly appealing in the context of their possible use for in-memory computing and hardware neural networks, as opposed to the von Neumann architecture Ielmini_inmemory . Current-controlled resistive switching in such devices typically occurs due to ion migration in a dielectric layer between the anode and the cathode resulting in the growth or rupture of conductive filaments Wang_memristors_review . Interestingly, despite considerable progress made on the technological side, there are still gaps in the understanding of the physical processes underlying resistive switching and retention of the resistive states in memristors. The reason is the stochasticity of the filament dynamics and possible interplay of various scales and effects, such as Joule heating, surface diffusion, strong electric fields, etc. Lee_review ; Ielmini_NatComm2019 An improved theory or simulation frameworks are particularly desirable when one descends to the nanoscale: the constrictions, i.e., the thinnest segments of the conductive filaments in the corresponding devices, allow for ballistic (quantum) charge transport and exhibit quantized conductance at room temperature, with the quantization being an attractive property to encode discrete states of the memristor Xue_review2019 ; Gao_Gquant ; Minnekhanov_OrgElec2019 ; Shvetsov_GquantPPX ; Kharlanov2022 . At the same time, interaction of quantum currents with the classical filament and its molecular environment constitutes a challenging task to describe, limiting rational design of such memristors.

In this letter, by no means aiming at a complete description of the dynamics of quantized-conductance filaments, we analyze a possible role of electron-induced, “recoil” forces acting on the ions Dundas_NNano2009 ; Todorov_PRB2010 in these dynamics, which is also potentially related to the extended lifetimes of filaments with well-quantized conductance values. The point is that conductance quantization in quasi-1D systems in the units of ( is the elementary charge, is the Planck’s constant) is not quite fundamental, being typical of “smooth”, adiabatic filaments Landauer ; Buttiker ; in principle, it does not have to hold for irregular filaments forming in memristors. However, the back reaction of quantum electrons passing through the filament could push it toward smoother shapes consistent with minimum recoil, integer electron transmission probability (transmittance), and thus quantized conductance. Indeed, in our recent study Kharlanov2022 , we identified that recoil forces should be large enough at voltages and conductances near to compete with the interatomic forces, potentially affecting the evolution of the filament. Together with that, our experiments showed that the thinnest filaments with the conductance and even , where the quantum recoil forces should be most pronounced, demonstrated the longest renention, i.e., stability with time Kharlanov2022 . However, Ref. Kharlanov2022 described conduction electrons using a semi-quantitative continuous free-electron model and lacked a dynamical simulation of the filament stochastic evolution, aiming at an order-of-magnitude estimation of the effects. Moreover, interatomic interactions in the filament were simply reduced to the latter having a certain amount of surface energy, like a liquid drop. In fact, since ion migration in memristors, e.g., surface diffusion, proceeds as a sequence of hops Ielmini_NatComm2019 , the lack of the dynamics strongly limits the model used in Ref. Kharlanov2022 , especially when it comes to simulate an actual resistive switching event. In contrast, in the present work we develop an atomistic quantum theory of electron recoil forces and incorporate it into a molecular-dynamics (MD) framework with realistic interatomic potentials to observe a quantum analogue of electromigration Electromigration triggering a resistive switching. The theory and simulations, described in the following sections, demonstrate that if the conditions for the quantized conductance are not satisfied, resistive switching can be facilitated by the growing recoil forces. This new resistive switching mechanism, which is important for memristors with atomic-scale filaments and high current densities, represents the main novelty of the present work, providing an alternative to the conventional mechanism due to ion migration in the electrostatic field between the cathode and the anode Lee_review ; Ielmini_NatComm2019 ; Xue_review2019 . Our results thus indicate that quantum recoil should be taken into account when describing memristive nanodevices and could potentially be used to achieve better retention characteristics of their quantized-conductance states.

2. The model. Similarly to earlier studies Dundas_NNano2009 ; Todorov_PRB2010 of current-induced forces, we use a semiclassical, Born–Oppenheimer (adiabatic) description of the nanoconstriction supporting a quantum current: the positions of the ions are treated classically, while the conduction electrons are described within the framework of nonequilibrium Green’s functions (NEGFs) applied to the tight-binding model Do_NEGFreview . Namely, the Hamiltonian of the system reads:

| (1) | |||||

| (2) | |||||

where and are the Planck constant and the electron mass, and are the coordinates and the momenta of the ions, respectively, is the “bare” ion-ion potential, and is the effective (Kohn–Sham) potential. For simplicity, we assume one orbital per atom, so that the electron field operator with spin projection is expanded as over an atomic-orbital basis set , with the coefficients being the electron annihilation operators. The transfer integrals and on-site energies for these orbitals form the matrix. The Ehrenfest equations for the atomic coordinates give , where the force acting on atom due to electrons equals:

| (3) | |||||

with the coefficients . Note that the total forces acting between the atoms contain the term coming from conduction electrons both in the presence and in the absence of the current through the system. The coefficients , albeit not expressible in terms of , can be estimated under reasonable assumptions. Namely, let us assume that (i) the Kohn–Sham potential can be represented as a sum of even contributions from individual atoms, (ii) the basis orbitals, in turn, possess a definite parity, and (iii) decays with a characteristic spatial scale between atom and its neighbors. Then , and vanishes identically due to parity. The nonnegligible coefficients that remain are , where , for the nearest neighbors of site (denoted below as ). The parameter is naturally expected to be around the inverse atomic radius. The resulting rough estimation of the force thus reads:

| (4) |

The expectation values in Eqs. (3), (4) are taken over a nonequilibrium many-body state describing a current of conduction electrons. In order to describe it using NEGFs, we introduce a customary partition of the atomic sites into two “leads” and the filament F connecting them:

| (5) |

so that denote columns with all annihilation operators in the leads or the filament, are the Hamiltonian matrices of these three subsystems, and couple the filament to the two leads. The retarded NEGF of the filament is introduced in a standard way,

| (6) |

where the self-energies stem from isolated-lead Green’s functions , and . The transmission probability in the form of Caroli is Caroli :

| (7) |

with the broadening operators , where are the spectral functions of the isolated leads.

Now, to find the expectation value in Eq. (3), we introduce “incident” wave functions in the isolated left or right leads, with energies , so that the scattering state of the whole system is given by NEGFs: e.g., for the waves coming from the left lead, . The rest of the calculation is straightforward and takes its simplest form if both atoms belong to the filament, :

| (8) | |||||

where is the Fermi–Dirac distribution in the lead with chemical potential . Observing that the term in braces gives nothing but the spectral function , we readily yield:

| (9) |

Used together with expression (3), this yields the electron-induced, “recoil” force:

| (10) |

where and are the chemical potentials of the leads, is the applied bias, and are the conduction band bottom and the Fermi level, respectively. The parameter controls a possible asymmetric voltage drop in the leads attached to the constriction Xue_review2019 ; in what follows, we will assume the symmetric case unless otherwise specified. Note that the energy integral in Eq. (10) extends to the whole conduction band, unlike the case of the Landauer–Büttiker formula for the conductance Landauer ; Buttiker :

| (11) |

However, as we noted above, the zero-current interatomic interaction (e.g., the force field used in MD simulations) should include both the bare term and the one given by Eq. (10) integrated over . Therefore, the extra, “renormalized” force acting on the atoms at a nonzero bias originates from the electronic states with , similarly to the Landauer formula.

It should also be noted that the mere momentum conservation law (which can be derived from the field-theoretic expression (3)) gives the total force acting on the constriction aligned with a certain axis :

| (12) | |||||

with the sum running through open channels in the leads with directions , wave numbers , and transmittances . This force vanishes for a perfectly ballistic conductance (); moreover, for identical leads, the integral cancels out except the segment, analogously to the Landauer formula:

| (13) |

For a single open channel at the Fermi surface and a small bias, , where is the Fermi momentum, which suggests that forces measured in tenths of can act on the thinnest filaments with their transmittances not close to unity.

Intuitively, it appears that similarly to the total force (13), the recoil forces (10) acting on individual atoms should also be suppressed in the ballistic regime with the transmittance close to an integer, which, according to Eq. (11), is characterized with a quantized conductance. To test this physical intuition, below we consider an analytically solvable case of a 1D chain of atoms, followed by an MD simulation of a nanofilament with realistic interatomic interactions and the quantum recoil on top of them. While the former system is meant to serve as an idealized “toy model”, letting us estimate the magnitude of the forces, their dependence on the bias, and correlation with the transmittance, the latter simulation will give a definitive answer on how the recoil forces can affect the evolution of a conducting filament and drive a resistive switching in a memristor.

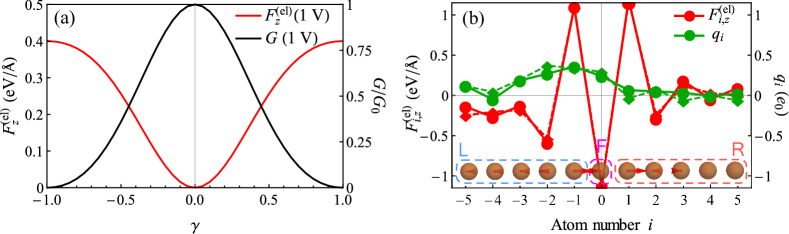

3. A quantum point contact in a 1D atomic chain. Let us number the atoms of such a chain, schematically shown in Fig. 1(b), with (right/left leads, respectively) and (the single central atom comprising the “filament”), so that at zero bias, the equilibrium positions of the atoms are proportional to the lattice parameter , , along the axis. The nearest-neighbor transfer integrals involving the central atom are , while all the other ; let us also take the on-site energies . As mentioned, within such a toy model, we are interested in estimating the electron-induced force acting on the central atom, treating all the other, lead atoms as fixed, and the electron transmittance of the chain. Now, working within the NEGF formalism described above, it is straightforward to find the “incident-wave” states, , , , and the self-energies . After that, the filament Green’s function (a matrix in our case) reads , together with Eq. (7) giving a closed-form expression for the transmittance:

| (14) |

where . The conductance at small biases, i.e., near the Fermi surface , is . Careful evaluation of the total force acting on the central atom () gives an expression:

| (15) | |||

where and the approximation (4) is used. One immediately observes that at zero bias, the force contains a prefactor of coming from and thus vanishes for a symmetric chain, . Below we quote the leading order of the zero-bias force in (the on-site energy does not contribute within the linear order):

| (16) | |||||

where we have made use of the fact that for our chain at half-filling, and . At a finite but small bias, assuming that , (which could be a result, e.g., of a deviation of the central atom from the origin along the axis), one can find the “renormalized” force:

| (17) |

In fact, it is the reflection symmetry mapping the single-atom “filament” onto itself and resulting in , , , , which forbids the contribution proportional to for a symmetric voltage drop (). In the next section, we will see that for larger filaments with their different ends coupled to different leads, this cancelation does not occur, leading to pronounced finite-bias recoil effects even for symmetric geometries. An estimation with the interatomic distance , , , , and gives the zero-bias force of about and the finite-bias contributions around . While the latter figure is quite small, the former one is considerably large at the scale of interatomic interactions and agrees with our above expectations of the total recoil force (13).

It is also interesting to note the effect of the applied bias on the stability of the position of the central atom. Indeed, assuming that the transfer integrals involving this atom are and , one has the equilibrium position with both the electronic force and the ionic contribution vanishing (due to and the symmetry, respectively). If the central atom infinitesimally deviates from , the total force acting on it becomes . Now, taking the ion-ion term in the form of a screened Coulomb interaction with the nearest neighbors, , where is the screened ion charge, we arrive at the following hessian:

| (18) |

While we assume that at zero bias to ensure the stability of the chain before applying the voltage, the latter can make it unstable if , above the critical value:

| (19) |

In particular, estimations show that the destabilizing zero-bias term in brackets can well compete with the stabilizing Coulomb one for partially screened charges. For example, for and , application of a voltage above results in a localized counterpart of the Peierls instability affecting the central atom’s position Peierls . In fact, this voltage-induced instability could become even more pronounced for more complex filament geometries, in particular, not exhibiting a reflection symmetry.

To complement the discussed analytical estimations, Fig. 1(a) demonstrates the total recoil force in a chain with versus the conductance (i.e., transmittance), while Fig. 1(b) resolves the force and the charges at different atoms around the quantum point contact. Note that according to Eq. (3), the recoil forces arise from interactions of the ions with Friedel oscillations of the electron density Friedel , thus, these forces should decay into the bulk together with the density oscillations. The amplitude of the forces, as we observe in Fig. 1(b), is large enough to perturb the geometry of the contact and either push it toward a configuration with a transmittance close to unity (when the recoil is negligible), or to facilitate ion migration. In this regard, it is worth noting that even for a constriction (four atoms) long, the conventional, electrostatic force driving ion migration in memrsitors should roughly be at the voltage of —compared with in Fig. 1(b)— which highlights the potentially important role of the recoil forces in the evolution of thinnest conductive filaments in memristive devices. Note in this connection that, although we have mentioned above that the recoil force should be renormalized in some way to avoid double counting upon its addition to the “bare”, classical ion-ion interaction , the oscillations in Fig. 1(b) reflect the quantum nature of the force and cannot be renormalized out after subtraction of the interference-free, classical term. Let us now switch to a more realistic numerical simulation of the effect of the recoil forces, to complement the outcomes of the present paragraph (in particular, to observe the renormalized recoil forces exceeding ).

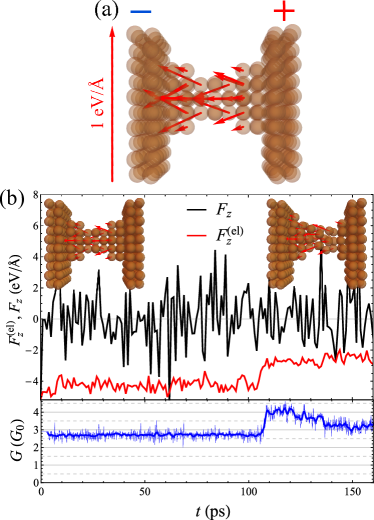

4. Simulation of a Cu filament with realistic interatomic forces. Of course, the filaments actually forming in memristors are neither one atom wide, as in Fig. 1(a), nor centrosymmetric: they result from stochastic ion migration, e.g., during the so-called electroforming of the memristor, which precedes its normal operation Lee_review . Therefore, the effect of the recoil forces on such, general filaments at room temperature may be beyond the conclusions drawn from the above 1D toy model at . To simulate the dynamics and study the recoil-driven ion migration along such filaments, we developed a custom MD code implementing the embedded-atom model (EAM) of the interatomic Cu-Cu forces Sheng_EAM and used a pre-generated typical initial geometry of a conductive filament between two ideal fcc electrodes [Fig. 2(a)], further warmed up to room temperature to obtain a more representative configuration. Following the adiabatic approximation, the recoil forces were calculated for instantaneous ion positions using Eq. (10) and then renormalized by subtracting their zero-bias values. Approximation (4) was used for the force coefficients with , where is the nearest-neighbor distance in the bulk fcc copper. When parameterizing the tight-binding model (2), the differences between the on-site energies of the atoms were neglected, while the transfer integrals were evaluated as , approximating the corresponding DFT results for states in Cu dimers. As for the Green’s functions of the semi-infinite leads, explicit Fourier-series expressions in the nearest-neighbor approximation were used for them, allowing one to avoid known poor conditioning issues PoorConditioning . Following a typical MD simulation methodology, we first minimized the energy of the system at absolute zero, then warmed it up to , and finally ran a production MD, using the Langevin thermostat. Being quite time-consuming, evaluation of the recoil forces was done each of the simulation, while the Langevin equation was integrated with a timestep.

The recoil forces calculated for the initial geometry [Fig. 2(a)] exhibit a strong asymmetry, despite the atomic positions for this configuration were intentionally chosen at the sites of an ideal fcc crystal. The asymmetry is caused by the bias applied to the anode (the right electrode in the figure): in agreement with Eq. (3), the forces point toward the cathode, which has a higher electron density due to the excess electron waves arriving there from the lead. The forces are measured in several tenths of , as in the case of the 1D atomic chain. As finite temperature is switched on, the conductance, initially being very close to , develops fluctuations around its quasisteady state and further features a sharp resistive switching around [Fig. 2(b)]. During all this time, the total recoil force remains directed toward the cathode, facilitating ion migration in this direction; in agreement with our above analysis, the force drops down when new conduction channels open. The result of the ion migration is seen in the initial and the final states of the filament presented in Fig. 2(b): a whole atomic layer near the anode gets rarified, with the atoms adding to the central part of the filament and thus enhancing the overall conductance. Note that, though the migration has the same direction as that of ions driven by the electric field, the latter is absent in our simulations, and the ion transport occurs solely due to momentum transfer from conduction electrons we (perhaps somewhat misleadingly) refer to as the “recoil” here. Thus, we conclude that a specific type of ion electromigration occurring due to a nonequilibrium quantum current of charge carriers can drive resistive switching in the atomic-scale-filaments regime.

5. Discussion. Finally, a couple of words should be said on the applicability of the approximations used above. First, the tight-binding model is a useful, easily parameterizable framework, but is more suitable for describing semiconductors, rather than metals. At the same time, in atomic-thickness filaments, the screening effect may be weaker than that in the bulk metal, with the real physics lying between the tight-binding model and the free-electron one considered recently in Ref. Kharlanov2022 . Second, in the context of these two models, a nontrivial thing to be noted regards the contributions of individual atoms to the total Kohn–Sham potential : the additive representation of the latter used in the present work clearly deserves further study and generalization. Third, in the above, we treated electron-current-induced forces in the mean-field fashion: this approximation rests on the fact that at the voltage of , around electrons per second pass through a filament with conductance , so that the time it takes a copper atom to shift by is enough for around 15, i.e., quite a lot of electrons to pass through the filament. Finally, for transition metals, including copper, localized orbitals are important, so that to achieve a better numerical accuracy, a multiscale ab initio+MD methodology appears more appropriate. For these further steps, however, the calculations within our simplified model may serve as a proof-of-principle study.

Last but not least, we would like to outline the novelty of the presented study. The main result is the quantum recoil-driven resistive switching mechanism demonstrated above, which works independently of the conventional ion migration in the electrostatic field. Namely, the forces acting on the ions and mediated by electrons get imbalanced due to the difference in the chemical potentials of the two leads, providing an additional driving force for ion migration. Note that unlike the continuous-medium approach applied in Ref. Kharlanov2022 to atomic-thickness filaments, the use of the more realistic atomistic potentials does not lead to the transversal capillary-bridge instability of the filament due to surface tension forces CapillaryInstabilities ; instead, the ion migration proceeds along the filament. Clearly, further simulations with larger and/or asymmetric filaments could reveal more interesting results, however, we leave them beyond the present work because of their higher computational demand. Also, though the very tools we have used for describing the quantum recoil forces—the NEGF formalism and the tight-binding model—are quite conventional and well-established Dundas_NNano2009 ; Todorov_PRB2010 ; Do_NEGFreview ; Caroli , the forces are, to the best of our knowledge, included in a dynamical description of the conducting filament for the first time.

6. Conclusion. To summarize, we have studied the effect of the “recoil” forces between the conduction electrons and the ions comprising a conductive filament on the geometry of the latter. As both analytical estimations and the MD simulation have revealed, the effect of the recoil should be quite pronounced for conductive filaments several atoms wide, like those formed in memristors exhibiting the conductance quantization effect. Unlike the classical volume and surface forces acting on the filament, the quantum recoil is intrinsically related to the transmittance and additionally destabilizes the filaments with the non-integer conductance. Our study thus provides a framework and highlights the importance of taking into account the charge-carrier recoil in the rational design of current and next generations of memristive nanodevices.

O.K. thanks Anton Minnekhanov for fruitful discussions. The work was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Project No. 20-07-00696). This work has been carried out using computing resources of the federal collective usage center Complex for Simulation and Data Processing for Megascience Facilities at NRC “Kurchatov Institute”.

References

- (1) L. Chua, IEEE Trans. Circuit Theory 18, 507 (1971).

- (2) D. B. Strukov, G. S. Snider, D. R. Stewart, and R. S. Williams, Nature 453, 80 (2008).

- (3) D. Ielmini and H.-S. P. Wong, IEEE Nanotechnol. Mag. 1, 333 (2018).

- (4) Z. Wang, H. Wu, G. W. Burr, et al., Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 173 (2020).

- (5) J. S. Lee, S. Lee, and T. W. Noh, Appl. Phys. Rev. 2, 031303 (2015).

- (6) W. Wang, M. Wang, E. Ambrosi, et al., Nat. Commun. 10, 81 (2019).

- (7) W. Xue, S. Gao, J. Shang, et al., Adv. Electron. Mater. 5, 1800854 (2019).

- (8) S. Gao, C. Chen, Z. Zhai, et al., Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 063504 (2014).

- (9) A. A. Minnekhanov, B. S. Shvetsov, M. M. Martyshov, et al., Org. Electron. 74, 89 (2019).

- (10) B. S. Shvetsov, A. A. Minnekhanov, A. A. Nesmelov, et al., Semiconductors 54, 1103 (2020).

- (11) O. G. Kharlanov, B. S. Shvetsov, V. V. Rylkov, and A. A. Minnekhanov, Phys. Rev. Applied 17, 054035 (2022).

- (12) D. Dundas, E. J. McEniry, and T. N. Todorov, Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 99 (2009).

- (13) T. N. Todorov, D. Dundas, and E. J. McEniry, Phys. Rev. B 81, 075416 (2010).

- (14) R. Landauer, IBM J. Res. Dev. 1, 223 (1957).

- (15) M. Büttiker, Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 2901 (1990).

- (16) K. H. Bevan, H. Guo, E. D. Williams, and Zh. Zhang, Phys. Rev. B 81, 235416 (2010).

- (17) V.-N. Do, Adv. Nat. Sci: Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 5, 033001 (2014).

- (18) C. Caroli, R. Combescot, P. Nozieres, and D. Saint-James, J. Phys. C 4, 916 (1971).

- (19) R. E. Peierls, Quantum Theory of Solids (Oxford University Press, London, 1955).

- (20) J. Friedel, Nuovo Cim. 7, 287 (1958).

- (21) H. W. Sheng, M. J. Kramer, A. Cadien, et al., Phys. Rev. B 83, 134118 (2011).

- (22) I. Rungger and S. Sanvito, Phys. Rev. B 78, 035407 (2008).

- (23) J. B. Bostwick and P. H. Steen, Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 47, 539 (2015).