Electronic band structure of a superconducting nickelate

probed by the Seebeck coefficient in the disordered limit

Abstract

Superconducting nickelates are a new family of strongly correlated electron materials with a phase diagram closely resembling that of superconducting cuprates. While analogy with the cuprates is natural, very little is known about the metallic state of the nickelates, making these comparisons difficult. We probe the electronic dispersion of thin-film superconducting 5-layer () and metallic 3-layer () nickelates by measuring the Seebeck coefficient, . We find a temperature-independent and negative for both and nickelates. These results are in stark contrast to the strongly temperature-dependent measured at similar electron filling in the cuprate La1.36Nd0.4Sr0.24CuO4. The electronic structure calculated from density functional theory can reproduce the temperature dependence, sign, and amplitude of in the nickelates using Boltzmann transport theory. This demonstrates that the electronic structure obtained from first-principles calculations provides a reliable description of the Fermiology of superconducting nickelates, and suggests that, despite indications of strong electronic correlations, there are well-defined quasiparticles in the metallic state. Finally, we explain the differences in the Seebeck coefficient between nickelates and cuprates as originating in strong dissimilarities in impurity concentrations. Our study demonstrates that the high elastic scattering limit of the Seebeck coefficient reflects only the underlying band structure of a metal, analogous to the high magnetic field limit of the Hall coefficient. This opens a new avenue for Seebeck measurements to probe the electronic band structures of relatively disordered quantum materials.

pacs:

74.72.Gh, 74.25.Dw, 74.25.F-I INTRODUCTION

Unconventional superconductivity remains one of the most active and challenging subfields of strongly correlated electron research, with cuprates posing some of the toughest experimental and theoretical challenges over the past three decades [1]. The origin of high- superconductivity in the cuprates remains a mystery in part due to the complex interplay of several competing states and relatively strong disorder. One approach to understanding the physics of high- is to replace copper entirely, for example with ruthenium or nickel, while maintaining the same square-lattice, transition metal oxide motif. Sr2RuO4 is a success of this approach [2], but it does not share the complex phase diagram of the cuprates.

The recent discovery of superconductivity in strontium-doped NdNiO2 [3, 4, 5] and stoichiometric Nd6Ni5O12 [6] presents an opportunity to explore the key ingredients for unconventional superconductivity by contrasting the physical properties of the nickelates with the cuprates. The nickelates contain cuprate-like NiO2 planes, and the family we study here is Ndn+1NinO2n+2, where indicates the number of NiO2 planes per unit cell [7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. While nickel in the member of the series—NdNiO2—has the same nominal electronic configuration as copper does in the cuprates, the finite- members have the nominal configuration of , where . This offers a mechanism for exploring the hole-doped phase diagram without introducing cation disorder.

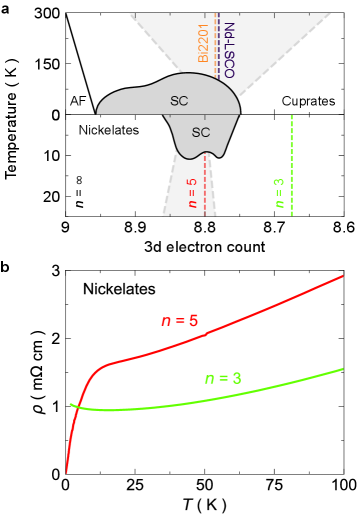

Superconducting nickelates exhibit many similarities with the cuprates. These include a phase diagram with a superconducting dome maximized around similar electron concentrations, evidence for a nodal superconducting gap [12], magnetism[13, 14], charge density waves [15, 16], and even a strange metal phase [17] (Fig. 1a). Conspicuously absent from this list are experimental comparisons of the electronic structure. To understand which aspects of the electronic dispersion are favorable for unconventional superconductivity, one must first understand how electrons interact in the normal metallic state.

The central difficulty is that most of the experimental techniques used to study electronic structures are incompatible with current superconducting nickelate samples. There have been attempts to measure the angle-integrated density of states [18], and there are recent angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) measurements on non-superconducting, single crystal nickelates [19], but ARPES remains out of reach for superconducting nickelate films due to surface quality issues. Similarly, quantum oscillations require metals with a defect density lower than what is currently available in even the cleanest films. This calls for the use of other techniques that are sensitive to the electronic structure and that are compatible with higher levels of elastic scattering from defects and with thin films.

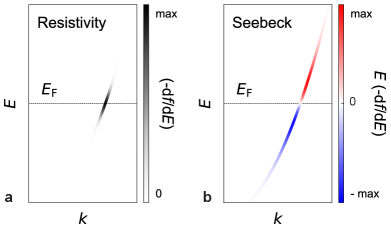

Thermoelectricity—as measured by the Seebeck coefficient —provides an alternative to probe the electronic band structure of a material. Unlike electrical transport, which is only sensitive to the electronic states in the immediate vicinity of the Fermi energy () (Fig. 2a), the Seebeck effect is sensitive to details of the electronic dispersion away from . Specifically, the Seebeck coefficient reflects the asymmetry of the dispersion above and below —it probes the asymmetry between occupied and unoccupied states (Fig. 2b), also called particle-hole asymmetry or energy asymmetry [20, 21]. In general, the Seebeck coefficient is defined by both the band structure and the energy dependence of the scattering rate. However, we will demonstrate that this coefficient is only determined by the band structure in the disordered limit, which is analogous to how the Hall coefficient becomes independent of scattering rate in the high-field limit. As the high-field limit is usually inaccessible in most metals, this makes the Seebeck effect a new powerful probe of the electronic dispersion of relatively disordered materials.

To investigate the electronic structure of the nickelates, we measured the Seebeck coefficient of a superconducting 5-layer nickelate Nd6Ni5O12 ( nickelate) with a transition onsetting at K (Fig. 1b)—as well as a more-overdoped, non-superconducting, 3-layer nickelate Nd4Ni3O8 ( nickelate) for comparison (Fig. 1b). We find that both the and nickelates share a similar temperature independent, negative . We show the electronic dispersion obtained from density functional theory (DFT) accounts for both the magnitude and sign of the temperature-independent Seebeck coefficient for the two compounds when calculated in the disordered limit.

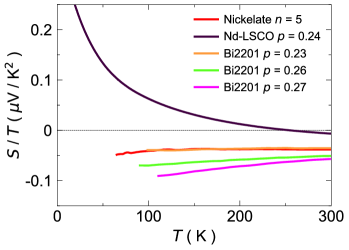

To justify the disordered limit, we compare the nickelate data to previous measurements of the Seebeck coefficient in hole doped cuprates with a similar electron count to the nickelate. First, we compare with measurements performed on a single crystal of La1.36Nd0.4Sr0.24CuO4 (Nd-LSCO ) [20] with a Seebeck coefficient that is positive and qualitatively different from that of the nickelates. Second, we compare with measurements performed on a single crystal of (Bi,Pb)2(Sr,La)2CuO6+δ (Bi2201 ) [21, 23] with an almost identical Seebeck coefficient to the nickelates. Despite their disparities, we show that the differences in Seebeck coefficients between nickelates and cuprates come from strong dissimilarities in impurity concentrations, and not necessarily from fundamental differences in the nature of the metallic state. Despite the presence of strong electronic correlations, the success of DFT and semi-classical transport calculations in our study provides evidence of well-defined quasiparticles responsible for charge and heat transport in both nickelates and cuprates.

II METHODS

Samples. The perovskite-like parent Ndn+1NinO3n+1 films ( and ) were synthesized by molecular beam epitaxy on (110)-orientated NdGaO3. The growth process used distilled ozone, substrate temperatures of 650-690 ∘C, and the NdNiO3 calibration procedure described in Ref. [24]. This synthesis was followed by a reduction process contained in a sealed glass ampoule, optimized with a process at C lasting three hours in order to reach the square-planar Ndn+1NinO2n+2 phases (this process is similar to the procedure in Ref. [6]). Using an electron-beam evaporator, contacts consisting of a 10 nm chromium sticking layer and 150 nm of gold were deposited in a Hall bar geometry such that the applied thermal gradient and measured Seebeck voltage were along the [001]-direction of the substrate.

The substrate material NdGaO3 has a high thermal conductivity that increases 30-fold between room temperature and 30 K [25], weakening the applied thermal gradient along the nickelate film. To mitigate this effect, we polished the NdGaO3 substrate to reduce its thickness from microns down to 100 - 150 microns using diamond lapping film. This served to increase the thermal gradient that generates the Seebeck voltage, which allowed us to measure the Seebeck effect down to 60 K, below which the thermal gradient becomes too small and the experiment cannot be performed reliably. This process necessarily involves a brief heat exposure during sample mounting. We minimized the degradation risk to the sample [26] by using low temperature crystal wax and mounting in an argon glove box; resistivity measurements taken before and after polishing showed no substantial changes.

Measurements. We measured the Seebeck coefficient using an AC technique used previously for cuprates [20]. An AC thermal excitation is generated by passing an electric current at frequency Hz through a 5 k strain gauge used as a heater to generate a thermal gradient in the sample. While the heat is carried primarily by the substrate, this also generates a thermal gradient along the film. We detect this AC thermal gradient at frequency , as well as the absolute temperature shift, using two type E thermocouples. An AC Seebeck voltage, , is also generated at a frequency in response to the thermal gradient. We measure this voltage with phosphor-bronze wires attached to the same contacts where the thermocouples measure : this eliminates uncertainties associated with the geometric factor.

The thermocouple and Seebeck voltages were amplified using EM Electronics A10 preamplifiers and detected using a MCL1-540 Synktek lock-in amplifier at the thermal excitation frequency . The Seebeck coefficient is then given by . The frequency was adjusted so that the thermoelectric voltage and the thermal gradient remained in phase.

Band structure calculations. The paramagnetic electronic structure of the and layered nickelates was calculated using density functional theory (DFT) combined with the projector augmented wave method, as implemented in the Vienna ab-initio simulation package [27]. We used a pseudopotential that treats the Nd electrons as core electrons. The in-plane lattice parameters were set to match the NdGaO3 substrate, and we optimized the out-of-plane lattice parameter. See Appendix A for more details on the band structure calculations.

Boltzmann transport. We fit a tight-binding model (Tables 1 and 2) to the DFT band structure calculated for the nickelates (Fig. 6). We combined the tight-binding model and Boltzmann transport theory to calculate the Seebeck coefficient. We applied the same algorithm that was used successfully in the cuprates [28, 29, 20, 30] to numerically evaluate the Seebeck coefficient for the nickelates.

III RESULTS

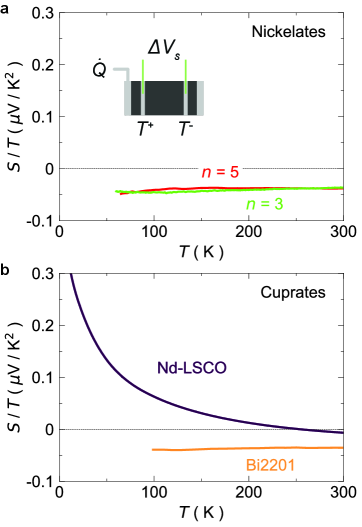

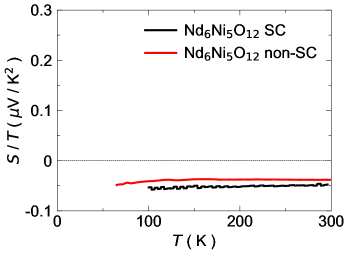

Seebeck coefficient. Fig. 3b shows the in-plane Seebeck coefficient of both the and samples. Both samples show an that is similar in magnitude, negative, and independent of temperature. We reproduced the Seebeck coefficient of the layer nickelate on a second sample (Appendix C), and the measured of the sample is similar to what was measured previously on the 3-layer nickelate La4Ni3O8 above its metal-to-insulator transition at 105 K [31].

The Seebeck coefficients of both nickelate samples are also comparable in magnitude and sign to that of the overdoped cuprate Bi2201 [21]. All of these measurements contrast with the optimally-doped cuprate Nd-LSCO [20], whose Seebeck coefficient is strongly temperature dependent and changes sign near room temperature (Fig. 3b). Both cuprates have a similar electron count to the nickelate.

The Seebeck coefficient in overdoped cuprates has been a puzzle for decades, with most cuprates showing a positive Seebeck coefficient similar to Nd-LSCO at low temperature, but Bi2201 showing a negative Seebeck coefficient. Our analysis is able to account for the differences in sign between Bi2201 and Nd-LSCO and explain the temperature dependence of Bi2201 for the first time, presenting a unified picture of the Seebeck coefficient across nickelates and overdoped cuprates.

Boltzmann calculations. We performed Boltzmann transport calculations to interpret the temperature dependence and the negative sign of in both the and nickelates (see Appendix B for more details). For a free-electron model (i.e. a circular Fermi surface), the sign of the Seebeck coefficient reflects the sign of the charge carriers—hole (positive) or electron (negative)—which is similar to the Hall coefficient. For a real material, the Seebeck coefficient is sensitive to the particle-hole asymmetry of the electronic dispersion (Fig. 2b), as well as to the particle-hole asymmetry of the scattering rate, and the resulting Seebeck coefficient can be of either sign.

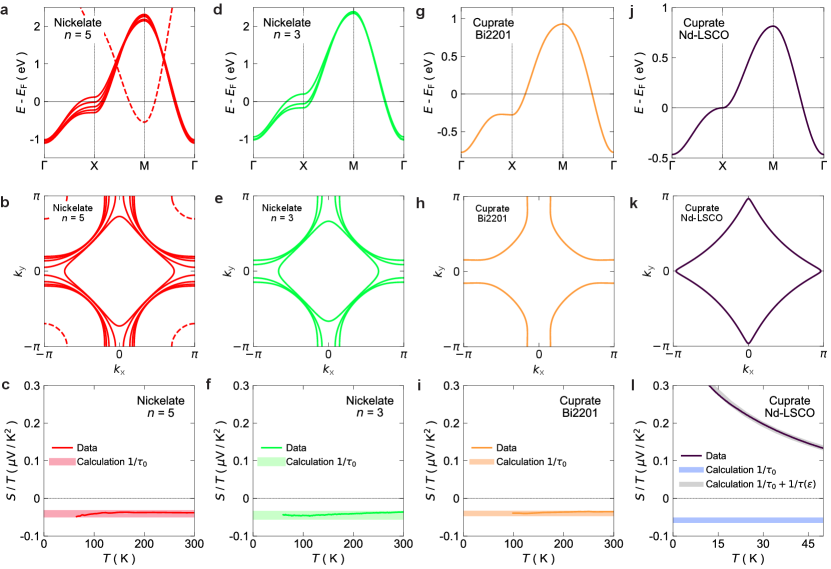

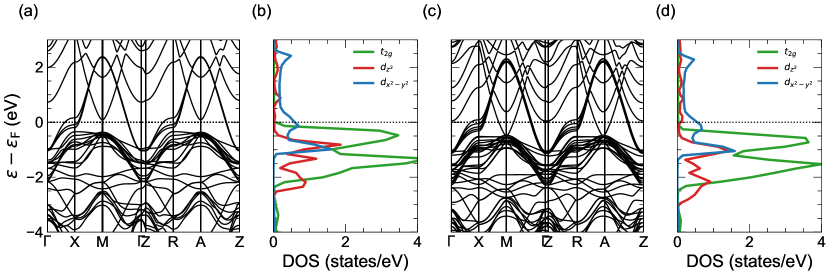

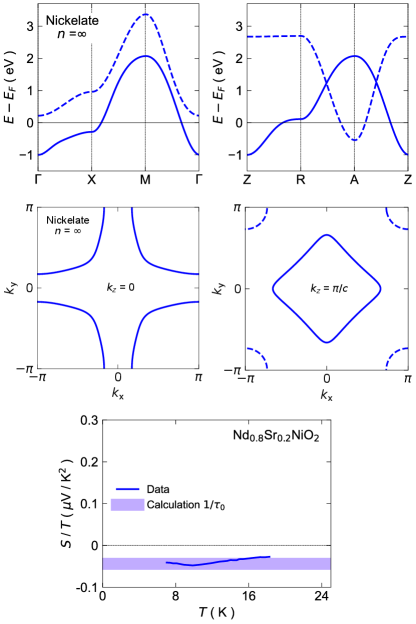

To perform Boltzmann transport calculations of the Seebeck coefficient, we require the electronic band dispersions for each material. For and nickelates, we fit a tight-binding model to the calculated DFT band structure [10, 11, 6]. For both materials, a single band per NiO2 layer crosses (Fig. 4a and 4a). For the compound, one additional band of Nd character crosses while for the material the Nd bands are well above the Fermi level (see Appendix A for more details). For the cuprates, we used the tight-binding models obtained from fitting angle dependent magnetoresistance and ARPES for Nd-LSCO [28, 32], and ARPES for Bi2201 [21] (Fig. 4g and 4g). The tight-binding model provides the velocities that serves to calculate the Seebeck coefficient.

We obtain excellent agreement between the calculated and measured for the nickelates by using the DFT band dispersions and a constant (energy and temperature independent) scattering rate, (Fig. 4c, 4f). We will justify this choice of scattering rate below.

For the cuprates, the calculations with a constant scattering rate predicts also exactly the right magnitude and sign for Bi2201; while the constant scattering rate calculation for Nd-LSCO gets both the sign and the temperature dependence incorrect. To obtain agreement between the Nd-LSCO data and Boltzmann transport calculations, an inelastic, particle-hole asymmetric scattering rate must be invoked (Fig. 4l from Gourgout et al. [20]). In this case, the scattering rate is not only energy dependent in Nd-LSCO (denoted ), but it is also linear-in-energy, with a different slope above and below the Fermi energy (see Appendix B and Gourgout et al. [20] for more details).

IV DISCUSSION

Effect of impurity scattering. The stark difference in between the nickelates and cuprates is somewhat surprising given the similarity of their electronic structures. These compounds have predominantly 3 bands crossing the Fermi energy, and the curvatures of the Fermi surfaces are not all that different—the single Fermi surface in Nd-LSCO essentially interpolates between the hole and electron-like Fermi surfaces found in the multi-layer nickelates (Fig. 4a, b, c). Given that the band structure is largely temperature-independent, the disparities in between the two families must originate in a difference in the scattering rate.

To understand this difference, we examine the relative amounts of disorder in the cuprate and nickelate samples by comparing the residual resistivities, . For the and nickelates, cm and respectively as measured by Pan et al. [6], which is significantly larger than the cm of Nd-LSCO [33] and cm of Bi2201 [34, 35, 23]. To quantify the disorder, we use the same Boltzmann transport framework we use to calculate to fit the elastic scattering rate to for each material. We find that is approximately times higher for the nickelate, and times for , compared to Nd-LSCO ( ps-1).

In the disordered limit, the scattering rate is predominately energy-independent (elastic), , the Seebeck coefficient becomes independent of scattering because it is the ratio of two quantities that are proportional to the scattering time: , with the Peltier coefficient and the electrical conductivity (more details are given in Appendix B). The high and the measured temperature-independent suggest that elastic scattering is indeed dominant in the nickelates, whereas we know the inelastic scattering plays a dominant role in the physics of Nd-LSCO [20]. The cuprate Bi2201, with a significantly higher level of disorder than Nd-LSCO, lies also in the disordered limit like the nickelates, which is confirmed by its temperature independent .

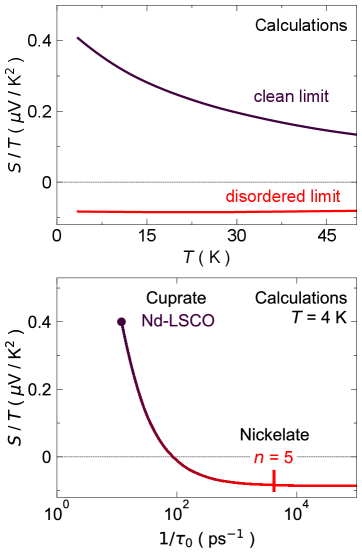

To further illustrate this argument, we recalculate the Seebeck coefficient for Nd-LSCO with the total scattering rate from Gourgout et al. [20] where we increase the relative amount of elastic scattering compared to the amount of inelastic scattering , going from the clean limit of Nd-LSCO to the disordered limit of the nickelates. Increasing from ps-1 to ps-1 while holding fixed, the calculated drops to a temperature-independent, negative value—very similar to what we measured in the nickelates (Fig. 5a) and what was measured for Bi2201. This confirms that the nickelate films and Bi2201 are dominated by elastic scattering and, in this limit, directly reflects the properties of the electronic bands rather than the energy dependence of the scattering rate. This proves the effectiveness of our approach to probe the electronic band dispersion of the nickelates using the Seebeck coefficient in the disordered limit. Note that the elastic scattering rate in the infinite layer nickelates is about 10 times smaller [17] than in the nickelate. However, Fig. 5b shows that the infinite layer nickelates are still in the limit where the elastic scattering rate dominates over the energy-asymmetric scattering and thus should also exhibit a negative and temperature-independent Seebeck coefficient.

Retrospectively, we can understand that the differences in between cleaner cuprates like Nd-LSCO [20] and LSCO [36], and dirtier cuprates like Bi2201 [21] comes only from the differences in impurity concentrations. The residual resistivity in Bi2201 is typically 5 to 20 larger [34, 35] than in LSCO and Nd-LSCO and the Seebeck coefficient in overdoped Bi2201 is therefore similar to the ones measured in the nickelates (Fig. 10 and Appendix G).

Fortuitously, the larger level of elastic disorder in the nickelates makes the Seebeck coefficient entirely insensitive to the scattering rate; similar to the high-field limit of the Hall coefficient, the high-elastic-scattering limit of reflects only the underlying electronic band structure.

The idea that the Seebeck coefficient is solely determined by the electronic band structure in the disordered limit is further supported by two additional examples from the literature: the infinite-layer superconducting nickelate Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 [37] and the delafossite PdCoO2 [38]. Quirk et al. [37] measured the Seebeck effect in Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2. This film had a residual resistivity of .cm—similar to our 3-layer nickelate sample and also in the disordered limit. We used Boltzmann transport and a tight-binding model based on the ARPES experiments of Sun et al. [39] to calculate the Seebeck coefficient. We find excellent agreement between the Seebeck data of Quirk et al. [37] and calculations in the disordered limit (see Fig. 9 and Appendix F).

Yordanov et al. [38] measured the Seebeck effect in thin films of the delafossite PdCoO2. These films were also in the disordered limit, with a residual resistivity 1000 larger than in single-crystal samples. Yordanov et al. [38] followed a procedure similar to the one we took for the 5-layer and 3-layer nickelates: they used the band structure from DFT and a standard Boltzmann transport package (that uses elastic scattering by default) to evaluate the Seebeck coefficient. They find perfect agreement between the measurements and the calculations. While Yordanov et al. [38] did not connect the success of their calculations to the disordered limit and the constant scattering rate hypothesis, this is another example of the broader validity of our conclusions.

Quasiparticles. -linear and resistivity was recently reported down to the lowest temperature in infinite layer nickelates [17] and Nd3Ni2O7 [40] under pressure. This suggests a strange-metal phase is present in the nickleates. A fit of its resistivity (Fig. 8)—as standardized in cuprates [22]—suggests that the nickelate is in proximity to this strange metal regime. While some theories propose that the strange metal regime is a phase without quasiparticles [41], the equally good determination of the Seebeck coefficient for both the or nickelates based on a semi-classical Boltzmann transport suggests that this is not the case here. This is in line with the success of several recent studies in cuprates that have demonstrated the validity of the semi-classical approach to describe transport in strange metals [28, 29, 20, 30] and Fermi liquids [36]. In addition, our study suggests that the band structure of the nickelates as calculated by DFT is a reliable description of the electronic structure of these materials, despite the absence of ARPES measurements to date.

V SUMMARY

We report the first Seebeck effect study of superconducting nickelates. We used the Seebeck coefficient in the disordered limit to probe the electronic band structure of both a superconducting 5-layer nickelate, as well as metallic 3-layer nickelate. We find the measured Seebeck coefficient is well-described by the band dispersion calculated with DFT, combined with semi-classical transport calculations. The calculated reproduces the amplitude, sign, and temperature dependence of the measured Seebeck coefficient, a rare achievement in predicting transport coefficients in quantum materials, and demonstrates that we have been able to probe the nature of the electronic states in superconducting nickelates—the first report of its kind.

Because of the similar electronic band structures between the nickelates and cuprates, we compare the Seebeck effect in the nickelates with Nd-LSCO – a cleaner cuprate – and Bi2201 – a more disordered cuprate. We find that the Seebeck coefficient for Bi2201 is in perfect agreement with experimental and theoritical data for nickelates. In the case of Nd-LSCO, however, we find a qualitative disagreement despite similarities in the electronic structure of the families. We show that the higher level of disorder present in nickelate thin films and in Bi2201, compared to Nd-LSCO, explains this difference.

As a corollary to our main result, our study highlights that the disordered limit of the Seebeck effect is a powerful and scattering-rate-independent probe of the electronic structure. This is opposite of other transport coefficients like the Hall effect, whose interpretation is opaque in the high scattering rate limit, especially for materials with anisotropic Fermi surfaces like the nickelates. This opens a new avenue of applications for the Seebeck effect in quantum materials by intentionally disordering otherwise-clean materials—for example with electron irradiation—to access intrinsic information about their electronic structure.

Acknowledgments

The work of B.J.R. and G.G. was supported as part of the Institute for Quantum Matter, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences under Award No. DE-SC0019331. G.A.P. and D.F.S. are primarily supported by U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering, under Award No. DE-SC0021925; and by NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Grant No. DGE-1745303. G.A.P. acknowledges additional support from the Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowship for New Americans. Q.S. was supported by the Science and Technology Center for Integrated Quantum Materials, NSF Grant No. DMR-1231319. J.A.M. acknowledges support from the Packard Foundation and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s EPiQS Initiative, Grant No. GBMF6760. Materials growth was supported by PARADIM under National Science Foundation (NSF) Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-2039380. We acknowledge the Cornell LASSP Professional Machine Shop for their contributions to designing and fabricating equipment used in this study. H.L and A.S.B acknowledge the support from NSF Grant No. DMR 2045826, the ASU Research Computing Center and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) through research allocation TG-PHY220006, which is supported by NSF grant number ACI-1548562 for HPC resources.

Appendix A DFT Computational Details

Density-functional theory calculations for the and nickelates were performed using the projector augmented plane-wave method as implemented in the VASP code [27]. For the exchange-correlation functional, we have used the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) version of the generalized gradient approximation [42]. The reduced Ruddlesden-Popper nickelates crystallize in a tetragonal structure where we have fixed the in-plane lattice constants to match those of the NdGaO3 substrate. The out-of-plane lattice constants were optimized and agree with the experimental values, namely Å and Å for the and materials, respectively [6]. The size of our plane-wave basis is determined by an energy cutoff of eV and integration in the Brillouin zone is performed on a -mesh for both materials.

Figure 6 provides a brief summary of the paramagnetic electronic structure of the and nickelates. The band structures reveal a band per NiO2 layer crossing the Fermi energy (), akin to the multi-layer cuprates. Interestingly, for the 5-layer nickelate, there are additional electron pockets at the Brillouin zone corners (M and A) coming from the rare-earth bands. For the 3-layer material, these “spectator” bands sit above . Indeed, the orbital-resolved density of states (DOS) reveals the dominant states are of Ni- character around the . The Ni- and Ni- () states are positioned well below and do not play a significant role in the low-energy physics of these materials. For a complete description of the electronic structure of the reduced Ruddlesden-Popper nickelates, see Refs. 10, 11.

Appendix B Boltzmann calculations

| Band | (meV) | |||

| Ni 1 | -1.101 | 396.6 | -0.1833 | 0.1042 |

| Ni 2 | -1.216 | 400.5 | -0.1458 | 0.0855 |

| Ni 3 | -0.765 | 420.9 | -0.2597 | 0.1075 |

| Ni 4 | -0.839 | 425.1 | -0.2483 | 0.0947 |

| Ni 5 | -0.906 | 417.1 | -0.2297 | 0.0795 |

| Nd | 3.157 | -650.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Band | (meV) | |||

| Ni 1 | -1.384 | 410.4 | -0.1532 | 0.0719 |

| Ni 2 | -1.037 | 426.2 | -0.2505 | 0.1071 |

| Ni 3 | -1.138 | 422.1 | -0.2205 | 0.0988 |

The Seebeck coefficient is given by the ratio of the Peltier coefficient to the electrical conductivity (with ), , where

| (1) |

| (2) |

with the electron charge, the Fermi-Dirac distribution and

| (3) |

where is the component of the quasiparticle velocity in the -direction, is the quasiparticle lifetime depending on both momentum and energy , and is given by a tight-binding model.

In order to calculate Seebeck coefficient of the and nickelates, we fitted a tight-binding model to the band dispersion calculated by DFT with

| (4) | ||||

with () and () the lattice constants for the () nickelate. The hopping parameters are found in the tables 1 and 2.

Two assumptions go into the Boltzmann calculations that have quantitative effects on the calculated value of . First, we assume that the scattering rate is the same on all bands. Because the Fermi velocity is of a similar magnitude on all bands, and because the strong elastic scattering is likely dominated by impurities that fix a real-space mean free path, it is reasonable to assume that the elastic mean free path is similar on all bands. This assumption introduces some uncertainty into the absolute value of but does not change it qualitatively as long as the scattering is not radically different (e.g. smaller by a factor of 10 or more) on one of the bands.

Second, we assume that the bandwidth calculated by DFT is the correct one. In real materials, electron-electron interactions tend to lower the overall bandwidth, which in turn reduces our tight-binding bandwidth and thus increases the calculated . While a proper measurement of the bandwidth is not available for these films, it is known that DFT has overestimated the bandwidth in lanthanum-based cuprates by about a factor of 2 [43, 28]. We incorporate a factor of 2 uncertainty in the bandwidth into our calculated in Fig. 4d and e.

Appendix C Sample comparison of nickelates

Here we compare the Seebeck coefficient of two samples of nickelate (Fig. 7). The superconducting sample was only measured down to 100 kelvin due to having a thicker substrate, which made it impossible within the temperature resolution to generate a sizable thermal gradient below that 100 kelvin to measure the Seebeck effect. Indeed, the thermal conductivity of the substrate, NdGaO3, increases dramatically at low temperature, short-circuiting any attempt to generate a thermal gradient with a reasonable amount of heat. The second sample was grown in similar conditions, but did not exhibit superconductivity due to the sensitivity of the superconducting state to few percent changes in the cation stoichiometry. We were able to reduce the thickness of that sample substrate down to microns to be able to measure the Seebeck effect down to lower temperature K on this sample. Fortunately, the Seebeck coefficients between the two samples are very similar and agree to within 15%. This difference may be accounted for by the varying levels of cation disorder introduced during the MBE-synthesis of the two samples, as well as by the randomness inherent to the chemical reduction process used in the synthesis of all square-planar nickelates. Nevertheless, the overall reproducibility confirms that the normal state is similar between these samples.

Appendix D Rare-earth band

One significant difference between the two nickelates is the presence of a neodymium band crossing the Fermi level for the superconducting, 5-layer nickelate. The role of this band is unknown—whether it contributes significantly to the conductivity, or even to the superconducting pairing [44]. To include the neodymium band in the Boltzmann transport calculations changes from nV / K2 with it to nV / K2 without. This 10% difference is likely to remain undetected within the experimental error bars. Therefore, it is difficult to conclude whether the rare-earth band participates in the measured Seebeck coefficient as calculations indicate its contribution remains marginal. This could suggest that the neodymium band does not play a dominant role in the metallic state of the 5-layer superconducting nickelate, which in turn suggests that it may not play a role in the superconductivity.

Appendix E Resistivity of the nickelates

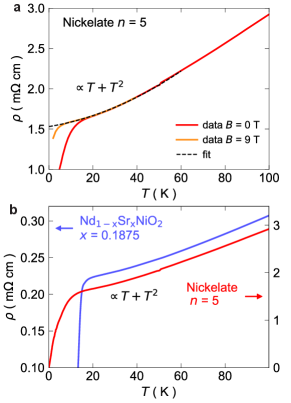

While -linear resistivity at high temperature is found in conventional metals like copper, because electrons scatter quasi-elastically off of phonons, this mechanism fades away at low temperature and this behavior does not persist down to . The term “strange metal” within the community of strongly correlated electron systems describes a metal whose resistivity remains linear in temperature down to [45, 46], an inexplicable behavior to date. Here we focus on the -linear component of the resistivity in the limit because it is unambiguously strange.

There are two caveats to demonstrate that the nickelate is a strange metal. First, superconductivity masks the limit of the resistivity. For this reason, we fit the resistivity at T down to the lowest temperature above . Reaching a higher field is difficult, as the sample tends to move in a magnetic field because of the torque in the substrate NdGaO3. Second, the resistivity is not purely linear in temperature nor is it purely quadratic. However, claiming that the nickelate is in the strange metal regime of the nickelates’ phase diagram comes from its resistivity fitted over a decade from 6 K to 60 K. The definition of the “strange metal regime” used in cuprates [22], iron-based [47] and organic superconductors [48], consists of the observation of a resistivity with a significant -linear component that persists down to . Perfectly -linear resistivity is only observed at a particular doping in these materials—away from this doping, the resistivity gains a component.

The strange metal regime has now also been reported in doped, infinite-layer nickelates with -linear, and resistivities [17] (Fig. 8b) and Nd3Ni2O7 [40]. Therefore, the strange metal regime in the nickelates follows the same doping dependence observed in the cuprates, iron-based and organic superconductors.

The fit of the resistivity of the nickelate sample includes a significant -linear component and can be described by as shown in Figure 8a, with values cm, cm / K, and cm / K2. And by comparison, the temperature dependence of the resistivity is very similar to the one of Nd1-xSrxNiO2 [17], a doping with behavior (Fig. 8).

Appendix F Seebeck coefficient in infinite-layer nickelates

The Seebeck coefficient was recently measured in the infinite-layer nickelate Nd1-xSrxNiO2 [37] at doping . The measured film has a large residual resistivity of m.cm, which, as we will show below, places it in the same disordered limit as the - and -layer nickelates.

We use the electronic dispersion obtained from recent ARPES measurement on La1-xSrxNiO2 at doping [39]—the same doping measured in the Seebeck experiments—with an identical crystal structure but with a different rare-earth that contributes only marginally to the transport (see Appendix D). Here, Sun et al. [39] was able to show that the ARPES electronic dispersion is in good agreement with the DFT calculations on the same material, corresponding to the hybridization of a nickel d-band with a La-band (Fig. 9 top).

Combining the ARPES electronic dispersion and Boltzmann transport, we compute and find a value in excellent agreement with the experiment (Fig. 9 bottom), similar to what we found for the -, -layer nickelates, and Bi2201. By computing the resistivity, we are able to show that the residual resistivity of m.cm from Quirk et al. [37] corresponds to a scattering rate ps. Fig. 5b places it in the same ballpark as -layer nickelate, i.e. in the disordered limit. This further supports our conclusion that Seebeck measurements in the disordered limit are sensitive only to the shape of the electronic band structure.

Appendix G Seebeck coefficient in cuprates

The doping range accessible can vary enormously from a cuprate compound to another, and finding a cuprate sample that shares the same electronic phase as the and nickelates and whose Seebeck coefficient has been measured is not a trivial task. This is why we chose the comparison with Nd-LSCO and Bi2201 , which are metallic and free from the pseudogap phase and charge order, similarly to the nickelates.

The Seebeck effect has been measured for as well in Nd-LSCO by Gourgout et al. [20], where Nd-LSCO is in the pseudogap phase with a Fermi surface transformation happening at [29]. Below , the behavior of remains similar to that of Nd-LSCO , meaning positive and strongly temperature dependent, with a larger amplitude.

Badoux et al. [49] measured the Seebeck effect in LSCO between and —a very different regime than Nd-LSCO and the nickelates. Above the charge density wave onset temperature, is temperature dependent and positive like Nd-LSCO. However, below the charge ordering temperature, becomes negative and remains strongly temperature dependent down to . In contrast, in Jin et al. [36], authors report Seebeck data on very overdoped LSCO , doping where the resistivity is quadratic in temperature and the Seebeck coefficient is qualitatively similar to Nd-LSCO but with a lower amplitude.

The closest comparison to the Seebeck effect found in the nickelates in this study is in the overdoped cuprate (Bi,Pb)2(Sr,La)2CuO6+δ (Bi2201) [21]. At high doping , the Seebeck effect is reported linear in temperature and negative—exactly as we find in the nickelates. We show this striking comparison in Fig. 10. Bi2201 is significantly more disordered than LSCO and Nd-LSCO, with typically residual resistivities cm or more [35], which is 5-20 times larger than LSCO and Nd-LSCO, meaning the samples come with much higher elastic scattering from defects.

References

- Keimer et al. [2015] B. Keimer, S. A. Kivelson, M. R. Norman, S. Uchida, and J. Zaanen, From quantum matter to high-temperature superconductivity in copper oxides, Nature 518, 179 (2015).

- Maeno et al. [1994] Y. Maeno, H. Hashimoto, K. Yoshida, S. Nishizaki, T. Fujita, J. G. Bednorz, and F. Lichtenberg, Superconductivity in a layered perovskite without copper, Nature 372, 10.1038/372532a0 (1994).

- Li et al. [2019] D. Li, K. Lee, B. Y. Wang, M. Osada, S. Crossley, H. R. Lee, Y. Cui, Y. Hikita, and H. Y. Hwang, Superconductivity in an infinite-layer nickelate, Nature 572, 624 (2019).

- Li et al. [2020] D. Li, B. Y. Wang, K. Lee, S. P. Harvey, M. Osada, B. H. Goodge, L. F. Kourkoutis, and H. Y. Hwang, Superconducting dome in infinite layer films, Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 027001 (2020).

- Zeng et al. [2020] S. Zeng, C. S. Tang, X. Yin, C. Li, M. Li, Z. Huang, J. Hu, W. Liu, G. J. Omar, H. Jani, Z. S. Lim, K. Han, D. Wan, P. Yang, S. J. Pennycook, A. T. S. Wee, and A. Ariando, Phase diagram and superconducting dome of infinite-layer thin films, Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 147003 (2020).

- Pan et al. [2022a] G. A. Pan, D. Ferenc Segedin, H. LaBollita, Q. Song, E. M. Nica, B. H. Goodge, A. T. Pierce, S. Doyle, S. Novakov, D. Córdova Carrizales, A. T. N’Diaye, P. Shafer, H. Paik, J. T. Heron, J. A. Mason, A. Yacoby, L. F. Kourkoutis, O. Erten, C. M. Brooks, A. S. Botana, and J. A. Mundy, Superconductivity in a quintuple-layer square-planar nickelate, Nature Materials 21, 160 (2022a).

- Poltavets et al. [2007] V. V. Poltavets, K. A. Lokshin, M. Croft, T. K. Mandal, T. Egami, and M. Greenblatt, Crystal structures of ln4ni3o8 (ln = la, nd) triple layer t‘-type nickelates, Inorganic Chemistry 46, 10887 (2007).

- Poltavets et al. [2009] V. V. Poltavets, M. Greenblatt, G. H. Fecher, and C. Felser, Electronic properties, band structure, and fermi surface instabilities of nickelate , isoelectronic with superconducting cuprates, Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 046405 (2009).

- Poltavets et al. [2010] V. V. Poltavets, K. A. Lokshin, A. H. Nevidomskyy, M. Croft, T. A. Tyson, J. Hadermann, G. Van Tendeloo, T. Egami, G. Kotliar, N. ApRoberts-Warren, A. P. Dioguardi, N. J. Curro, and M. Greenblatt, Bulk magnetic order in a two-dimensional () nickelate, isoelectronic with superconducting cuprates, Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 206403 (2010).

- LaBollita and Botana [2021] H. LaBollita and A. S. Botana, Electronic structure and magnetic properties of higher-order layered nickelates: , Phys. Rev. B 104, 035148 (2021).

- LaBollita et al. [2022] H. LaBollita, M.-C. Jung, and A. S. Botana, Many-body electronic structure of layered nickelates, Phys. Rev. B 106, 115132 (2022).

- Botana and Norman [2020] A. Botana and M. Norman, Similarities and differences between LaNiO2 and CaCuO2 and implications for superconductivity, Physical Review X 10, 011024 (2020).

- Lu et al. [2021] H. Lu, M. Rossi, A. Nag, M. Osada, D. F. Li, K. Lee, B. Y. Wang, M. Garcia-Fernandez, S. Agrestini, Z. X. Shen, E. M. Been, B. Moritz, T. P. Devereaux, J. Zaanen, H. Y. Hwang, K.-J. Zhou, and W. S. Lee, Magnetic excitations in infinite-layer nickelates, Science 373, 213 (2021), publisher: American Association for the Advancement of Science.

- Fowlie et al. [2022] J. Fowlie, M. Hadjimichael, M. M. Martins, D. Li, M. Osada, B. Y. Wang, K. Lee, Y. Lee, Z. Salman, T. Prokscha, J.-M. Triscone, H. Y. Hwang, and A. Suter, Intrinsic magnetism in superconducting infinite-layer nickelates, Nature Physics 18, 1043 (2022), arXiv:2201.11943.

- Rossi et al. [2022] M. Rossi, M. Osada, J. Choi, S. Agrestini, D. Jost, Y. Lee, H. Lu, B. Y. Wang, K. Lee, A. Nag, Y.-D. Chuang, C.-T. Kuo, S.-J. Lee, B. Moritz, T. P. Devereaux, Z.-X. Shen, J.-S. Lee, K.-J. Zhou, H. Y. Hwang, and W.-S. Lee, A broken translational symmetry state in an infinite-layer nickelate, Nature Physics 18, 869 (2022).

- Tam et al. [2022] C. C. Tam, J. Choi, X. Ding, S. Agrestini, A. Nag, M. Wu, B. Huang, H. Luo, P. Gao, M. García-Fernández, L. Qiao, and K.-J. Zhou, Charge density waves in infinite-layer NdNiO2 nickelates, Nature Materials 21, 1116 (2022).

- Lee et al. [2023] K. Lee, B. Y. Wang, M. Osada, B. H. Goodge, T. C. Wang, Y. Lee, S. Harvey, W. J. Kim, Y. Yu, C. Murthy, S. Raghu, L. F. Kourkoutis, and H. Y. Hwang, Linear-in-temperature resistivity for optimally superconducting (Nd,Sr)NiO2, Nature 619, 288 (2023).

- Chen et al. [2022] Z. Chen, M. Osada, D. Li, E. M. Been, S.-D. Chen, M. Hashimoto, D. Lu, S.-K. Mo, K. Lee, B. Y. Wang, F. Rodolakis, J. L. McChesney, C. Jia, B. Moritz, T. P. Devereaux, H. Y. Hwang, and Z.-X. Shen, Electronic structure of superconducting nickelates probed by resonant photoemission spectroscopy, Matter 5, 1806 (2022).

- Li et al. [2022] H. Li, P. Hao, J. Zhang, K. Gordon, A. G. Linn, H. Zheng, X. Zhou, J. F. Mitchell, and D. S. Dessau, Electronic structure and correlations in planar trilayer nickelate Pr4Ni3O8, arXiv.2207.13633 10.48550/arXiv.2207.13633 (2022).

- Gourgout et al. [2022] A. Gourgout, G. Grissonnanche, F. Laliberté, A. Ataei, L. Chen, S. Verret, J.-S. Zhou, J. Mravlje, A. Georges, N. Doiron-Leyraud, and L. Taillefer, Seebeck coefficient in a cuprate superconductor: Particle-hole asymmetry in the strange metal phase and fermi surface transformation in the pseudogap phase, Physical Review X 12, 011037 (2022).

- Kondo et al. [2005] T. Kondo, T. Takeuchi, U. Mizutani, T. Yokoya, S. Tsuda, and S. Shin, Contribution of electronic structure to thermoelectric power in (Bi,Pb)2(Sr,La )2CuO6+δ, Physical Review B 72, 024533 (2005).

- Cooper et al. [2009] R. A. Cooper, Y. Wang, B. Vignolle, O. J. Lipscombe, S. M. Hayden, Y. Tanabe, T. Adachi, Y. Koike, M. Nohara, H. Takagi, C. Proust, and N. E. Hussey, Anomalous criticality in the electrical resistivity of la2-xsrxcuo4, Science 323, 603 (2009).

- Berben et al. [2022] M. Berben, S. Smit, C. Duffy, Y.-T. Hsu, L. Bawden, F. Heringa, F. Gerritsen, S. Cassanelli, X. Feng, S. Bron, E. Van Heumen, Y. Huang, F. Bertran, T. K. Kim, C. Cacho, A. Carrington, M. S. Golden, and N. E. Hussey, Superconducting dome and pseudogap endpoint in Bi2201, Physical Review Materials 6, 044804 (2022).

- Pan et al. [2022b] G. A. Pan, Q. Song, D. Ferenc Segedin, M.-C. Jung, H. El-Sherif, E. E. Fleck, B. H. Goodge, S. Doyle, D. Córdova Carrizales, A. T. N’Diaye, P. Shafer, H. Paik, L. F. Kourkoutis, I. El Baggari, A. S. Botana, C. M. Brooks, and J. A. Mundy, Synthesis and electronic properties of Ndn+1NinO3n+1 Ruddlesden-Popper nickelate thin films, Phys. Rev. Materials 6, 055003 (2022b).

- Schnelle et al. [2001] W. Schnelle, R. Fischer, and E. Gmelin, Specific heat capacity and thermal conductivity of NdGaO3 and LaAlO3 single crystals at low temperatures, Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 34, 846 (2001).

- Ding et al. [2022] X. Ding, S. Shen, H. Leng, M. Xu, Y. Zhao, J. Zhao, X. Sui, X. Wu, H. Xiao, X. Zu, B. Huang, H. Luo, P. Yu, and L. Qiao, Stability of superconducting Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 thin films, Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy 65, 267411 (2022).

- Kresse and Furthmüller [1996] G. Kresse and J. Furthmüller, Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set, Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

- Grissonnanche et al. [2021] G. Grissonnanche, Y. Fang, A. Legros, S. Verret, F. Laliberté, C. Collignon, J. Zhou, D. Graf, P. A. Goddard, L. Taillefer, and B. J. Ramshaw, Linear-in temperature resistivity from an isotropic planckian scattering rate, Nature 595, 667 (2021).

- Fang et al. [2022] Y. Fang, G. Grissonnanche, A. Legros, S. Verret, F. Laliberté, C. Collignon, A. Ataei, M. Dion, J. Zhou, D. Graf, M. J. Lawler, P. A. Goddard, L. Taillefer, and B. J. Ramshaw, Fermi surface transformation at the pseudogap critical point of a cuprate superconductor, Nature Physics 18, 558 (2022).

- Ataei et al. [2022] A. Ataei, A. Gourgout, G. Grissonnanche, L. Chen, J. Baglo, M.-E. Boulanger, F. Laliberté, S. Badoux, N. Doiron-Leyraud, V. Oliviero, S. Benhabib, D. Vignolles, J.-S. Zhou, S. Ono, H. Takagi, C. Proust, and L. Taillefer, Electrons with Planckian scattering obey standard orbital motion in a magnetic field, Nature Physics , 1 (2022), publisher: Nature Publishing Group.

- Cheng et al. [2012] J.-G. Cheng, J.-S. Zhou, J. B. Goodenough, H. D. Zhou, K. Matsubayashi, Y. Uwatoko, P. P. Kong, C. Q. Jin, W. G. Yang, and G. Y. Shen, Pressure effect on the structural transition and suppression of the high-spin state in the triple-layer , Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 236403 (2012).

- Horio et al. [2018] M. Horio, K. Hauser, Y. Sassa, Z. Mingazheva, D. Sutter, K. Kramer, A. Cook, E. Nocerino, O. K. Forslund, O. Tjernberg, M. Kobayashi, A. Chikina, N. B. M. Schröter, J. A. Krieger, T. Schmitt, V. N. Strocov, S. Pyon, T. Takayama, H. Takagi, O. J. Lipscombe, S. M. Hayden, M. Ishikado, H. Eisaki, T. Neupert, M. Månsson, C. E. Matt, and J. Chang, Three-dimensional fermi surface of overdoped la-based cuprates, Physical Review Letters 121, 077004 (2018).

- Daou et al. [2009] R. Daou, N. Doiron-Leyraud, D. LeBoeuf, S. Y. Li, F. Laliberté, O. Cyr-Choinière, Y. J. Jo, L. Balicas, J.-Q. Yan, J.-S. Zhou, J. B. Goodenough, and L. Taillefer, Linear temperature dependence of resistivity and change in the fermi surface at the pseudogap critical point of a high- superconductor, Nature Physics 5, 31 (2009).

- Kondo et al. [2006] T. Kondo, T. Takeuchi, S. Tsuda, and S. Shin, Electrical resistivity and scattering processes in studied by angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy, Phys. Rev. B 74, 224511 (2006).

- Ayres et al. [2021] J. Ayres, M. Berben, M. Čulo, Y.-T. Hsu, E. van Heumen, Y. Huang, J. Zaanen, T. Kondo, T. Takeuchi, J. R. Cooper, C. Putzke, S. Friedemann, A. Carrington, and N. E. Hussey, Incoherent transport across the strange-metal regime of overdoped cuprates, Nature 595, 661 (2021).

- Jin et al. [2021] H. Jin, A. Narduzzo, M. Nohara, H. Takagi, N. E. Hussey, and K. Behnia, Positive Seebeck coefficient in highly doped La2-xSrxCuO4 (=0.33); its origin and implication, Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 90, 053702 (2021).

- Quirk et al. [2023] N. P. Quirk, D. Li, B. Y. Wang, H. Y. Hwang, and N. P. Ong, The vortex-nernst effect in a superconducting infinite-layer nickelate (2023), arXiv:2309.03170 [cond-mat.supr-con] .

- Yordanov et al. [2019] P. Yordanov, W. Sigle, P. Kaya, M. E. Gruner, R. Pentcheva, B. Keimer, and H.-U. Habermeier, Large thermopower anisotropy in pdco o 2 thin films, Physical Review Materials 3, 085403 (2019).

- Sun et al. [2024] W. Sun, Z. Jiang, C. Xia, B. Hao, Y. Li, S. Yan, M. Wang, H. Liu, J. Ding, J. Liu, Z. Liu, J. Liu, H. Chen, D. Shen, and Y. Nie, Electronic Structure of Superconducting Infinite-Layer Lanthanum Nickelates (2024), 2403.07344 [cond-mat] .

- Sun et al. [2023] H. Sun, M. Huo, X. Hu, J. Li, Z. Liu, Y. Han, L. Tang, Z. Mao, P. Yang, B. Wang, J. Cheng, D.-X. Yao, G.-M. Zhang, and M. Wang, Signatures of superconductivity near 80 K in a nickelate under high pressure, Nature 621, 493 (2023).

- Hartnoll and Mackenzie [2022] S. A. Hartnoll and A. P. Mackenzie, Colloquium: Planckian dissipation in metals, Rev. Mod. Phys. 94, 041002 (2022).

- Perdew et al. [1996] J. P. Perdew, K. Burke, and M. Ernzerhof, Generalized gradient approximation made simple, Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

- Markiewicz et al. [2005] R. S. Markiewicz, S. Sahrakorpi, M. Lindroos, H. Lin, and A. Bansil, One-band tight-binding model parametrization of the high- cuprates including the effect of dispersion, Physical Review B 72, 054519 (2005).

- Li and Louie [2022] Z. Li and S. G. Louie, Two-gap superconductivity and decisive role of rare-earth electrons in infinite-layer nickelates, arXiv:2210.12819 (2022).

- Bruin et al. [2013] J. a. N. Bruin, H. Sakai, R. S. Perry, and A. P. Mackenzie, Similarity of scattering rates in metals showing t-linear resistivity, Science 339, 804 (2013).

- Legros et al. [2019] A. Legros, S. Benhabib, W. Tabis, F. Laliberté, M. Dion, M. Lizaire, B. Vignolle, D. Vignolles, H. Raffy, Z. Z. Li, P. Auban-Senzier, N. Doiron-Leyraud, P. Fournier, D. Colson, L. Taillefer, and C. Proust, Universal t -linear resistivity and planckian dissipation in overdoped cuprates, Nature Physics 15, 142 (2019).

- Fang et al. [2009] L. Fang, H. Luo, P. Cheng, Z. Wang, Y. Jia, G. Mu, B. Shen, I. I. Mazin, L. Shan, C. Ren, and H.-H. Wen, Roles of multiband effects and electron-hole asymmetry in the superconductivity and normal-state properties of , Phys. Rev. B 80, 140508 (2009).

- Doiron-Leyraud et al. [2009] N. Doiron-Leyraud, P. Auban-Senzier, S. René de Cotret, C. Bourbonnais, D. Jérome, K. Bechgaard, and L. Taillefer, Correlation between linear resistivity and in the bechgaard salts and the pnictide superconductor , Phys. Rev. B 80, 214531 (2009).

- Badoux et al. [2016] S. Badoux, S. A. A. Afshar, B. Michon, A. Ouellet, S. Fortier, D. LeBoeuf, T. P. Croft, C. Lester, S. M. Hayden, H. Takagi, K. Yamada, D. Graf, N. Doiron-Leyraud, and L. Taillefer, Critical doping for the onset of fermi-surface reconstruction by charge-density-wave order in the cuprate superconductor , Phys. Rev. X 6, 021004 (2016).