Extremely long convergence times in a 3D GCM simulation of the sub-Neptune Gliese 1214b

Abstract

We present gray gas general circulation model (GCM) simulations of the tidally locked mini-Neptune GJ 1214b. On timescales of 1,000-10,000 Earth days, our results are comparable to previous studies of the same planet, in the sense that they all exhibit two off-equatorial eastward jets. Over much longer integration times (50,000-250,000 Earth days) we find a significantly different circulation and observational features. The zonal-mean flow transitions from two off-equatorial jets to a single wide equatorial jet that has higher velocity and extends deeper. The hot spot location also shifts eastward over the integration time. Our results imply a convergence time far longer than the typical integration time used in previous studies. We demonstrate that this long convergence time is related to the long radiative timescale of the deep atmosphere and can be understood through a series of simple arguments. Our results indicate that particular attention must be paid to model convergence time in exoplanet GCM simulations, and that other results on the circulation of tidally locked exoplanets with thick atmospheres may need to be revisited.

1 Introduction

During the last few decades, more than 3700 planets orbiting other stars have been discovered and confirmed. The majority of these planets were discovered via the transit method. Many of the planets discovered by the transit method are close to their host star and are expected to be tidally locked, implying that only one side of the planet receives stellar radiation from the host star. This type of forcing provides the conditions for the development of rich and interesting atmospheric dynamics without any direct analog in solar System (Seager and Deming, 2010; Showman et al., 2013).

Observing the atmospheric dynamics of exoplanets is difficult, but substantial progress has been made over the last few years. Currently, only a few observational features can be linked to atmospheric dynamics. The transit phase curve can be inverted to produce a longitudinal temperature distribution (e.g., Knutson et al., 2007; Demory et al., 2016), which can provide information on dynamical features such as zonal jets. The “featureless” transit spectra of the warm sub-Neptune/super-Earth111Previously, exoplanets such as GJ 1214b have often been referred to as “super-Earths.” Here we use the alternative term “sub-Neptune” for this planet and others of up to around 10 Earth masses that possess a thick atmosphere. GJ 1214b (Charbonneau et al., 2009) and the Neptune-mass exoplanet GJ 436b (Knutson et al., 2014; Kreidberg et al., 2014) hint at the existence of high and dense clouds, which require strong vertical updrafts in the upper atmosphere. Crossfield and Kreidberg (2017) summarized the relationship between the amplitude of the spectral features of six sub-Neptunes and their planetary parameters. Super-Earths and sub-Neptunes are particularly interesting because they represent a class of planets that are not in our solar system. This makes them valuable targets for future observations and theoretical study.

Exoplanet atmospheric dynamics can be modeled in various ways. Three-dimensional general circulation models (GCMs) are widely used because of their ability to generate three-dimensional dynamical fields, model various physical processes, and simulate observational signals. For tidally locked planets, phase curves generated by GCMs have been used to predict observations (e.g., Zhang and Showman, 2017) and compare with observational results (e.g., Zellem et al., 2014). Most of the GCMs are based on solving primitive equations, while Mayne et al. (2019) pointed out that some assumptions of primitive equations break down in the regime of a sub-Neptune’s atmosphere, and the strength of superrotation weakens when they solve the full Navier-Stokes equations. In this study, we focus on the GCMs that solve primitive equations to enable intercomparison with previous studies.

Multiple previous studies have used GCMs to study the dynamical regimes of strongly irradiated exoplanets with thick gas envelopes (e.g., Cho et al., 2003; Showman et al., 2009, 2012; Heng et al., 2011; Rauscher and Menou, 2012; Komacek and Showman, 2016; Zhang and Showman, 2017; Mayne et al., 2017). The atmospheric dynamics of tidally locked sub-Neptunes have also been investigated with GCMs. In particular, several previous studies have investigated the circulation of GJ 1214b (Menou, 2012a; Zalucha et al., 2013; Kataria et al., 2014; Charnay et al., 2015a, b; Drummond et al., 2018; Mayne et al., 2019).

For exoplanets that have a significant gas envelope and are tidally locked to their host stars, superrotation and jet formation are discovered in many GCM simulations. These phenomena are believed to be linked to the shape of the thermal phase curve and shift of the hot spot (e.g., Knutson et al., 2007). Many theories have been developed for superrotation, jet formation, and atmospheric dynamics on tidally locked exoplanets, and their observational implications have also been explored (e.g., Showman and Polvani, 2011; Tsai et al., 2014; Zhang and Showman, 2017; Hammond and Pierrehumbert, 2018). Because there are still relatively few direct observational constraints on exoplanet circulation, these theories are anchored by comparison with the GCM results.

A major challenge in GCM simulations of a gas planet is that the deep atmosphere has a long equilibrium timescale, and model convergence is not well understood. Nonetheless, the standard approach in previous studies has been to initialize the atmosphere with an equilibrium vertical temperature profile that is horizontally homogeneous, and run the 3D GCMs for a few thousand Earth days (unless otherwise specified, all “days” in this paper are Earth days). Some previous studies have found that the choice of boundary condition and artificial drag can lead to differences in model results (e.g., Liu and Showman, 2013; Cho et al., 2015; Carone et al., 2019). However, the dependence of flow structure on the equilibrium timescale of the deep atmosphere has only been investigated by a few previous studies. Mayne et al. (2017) studied the evolution of the deep atmosphere of the hot Jupiter HD 209458b, and found a long evolutionary timescale. Carone et al. (2019) studied the dynamical feedback between the deep atmosphere and observable atmosphere by prescribing a Newtonian relaxation scheme in the deep atmosphere of their hot Jupiter simulations. They discussed how reducing the radiative time scale of the deep atmosphere modifies the flow structure.

In the solar System, several previous studies have investigated processes that could be driving the jet structure at various depths on Jupiter and Saturn (e.g., Galperin et al., 2004; Heimpel et al., 2005; Kaspi and Flierl, 2007; Read et al., 2007; Schneider and Liu, 2009; Liu and Schneider, 2010; Young et al., 2019). Most notably, recent gravity data from NASA’s Juno mission have indicated that the jets observed in the surface weather layer of Jupiter extend thousands of meters deep into the atmosphere, probably to the depth at which magnetic dissipation becomes effective (Kaspi et al., 2018). This suggests that similar dynamical connections between the observable weather layer and the deep atmosphere may exist on exoplanets. Young et al. (2019) ran GCM simulations of Jupiter for 130,000-150,000 Earth days to allow the deep region of the 18 bar atmosphere to come into equilibrium, and studied the dynamical properties of the Jovian atmosphere.

In this study, we present a suite of gray gas GCM simulations that we have performed using the Generic LMDZ GCM to investigate this issue. To allow intercomparison with a range of previous studies, our simulations use the same planetary parameters as those of the sub-Neptune GJ 1214b. Here we integrate our model for a much longer time than was done in previous work, with the aim of investigating the convergence time.

In Section 2, we describe the GCM and simulation setup. In Section 3, we show the model results, with a focus on the long timescale required for convergence. We also discuss how important dynamical features change with time, and consider the observational implications. In Section 4, we discuss the wider implications of our results, and give suggestions for future work. In Section 5 we present our summary and conclusions.

2 Method

We used the generic LMDZ GCM, which has been developed specifically for modeling exoplanets and paleoclimate. It has previously been used to study the present and past climates of Earth, Mars, Venus, Titan, and exoplanets (Wordsworth et al., 2011, 2013; Forget et al., 2013; Leconte et al., 2013; Charnay et al., 2014). The dynamical core (Hourdin et al., 2006) solves the primitive equations using a finite difference method on an Arakawa C grid. The scheme is constructed to conserve enstrophy and total angular momentum, and scale-selective hyperdiffusion with a characteristic timescale of 16,000 s is used in the horizontal plane for stability (Forget et al., 1999). In this paper, we used a spatial resolution of 64 48 45 in longitude, latitude and altitude. The vertical layers are equally spaced in log-pressure, where the highest pressure is 80 bar (8 MPa) and the top level pressure is 1.3 Pa. The dynamical time step is 90 s, and the radiative time step is 450 s. For comparison, we also performed two sets of experiments where the highest pressure was 5 bar and 10 bar respectively. Here we mainly focus on the 80 bar experiment, which demonstrates the long equilibrium timescale most effectively. In Section 3, we discuss the effects of our choice of bottom boundary on the equilibrium timescale.

We focus on the planet GJ 1214b, which is a warm sub-Neptune (planetary radius , mass ; Charbonneau et al., 2009) orbiting an M dwarf. The planet’s low density implies a thick atmosphere, and its relatively featureless transit spectrum suggests the presence of high and thick clouds (Bean et al., 2011; Kreidberg et al., 2014). Here we assume that GJ 1214b has a circular orbit and is tidally locked to its host star, and that the stellar flux at the substellar point is 23,600 . We assume an internal energy flux of 0.73 . This value corresponds to an intrinsic temperature of 60 K, as suggested by Rogers and Seager (2010), and matches the estimation in Thorngren et al. (2019).

We used a two-stream gray gas radiative transfer scheme, with a shortwave mass absorption coefficient and a longwave mass absorption coefficient . We chose and to match the globally averaged temperature profile with that of a 1D correlated- radiative-convective model (Miller-Ricci and Fortney, 2010; Menou, 2012a) corresponding to an atmosphere of solar composition. Analytically, the 1D gray gas solution is (following Pierrehumbert (2011))

| (1) |

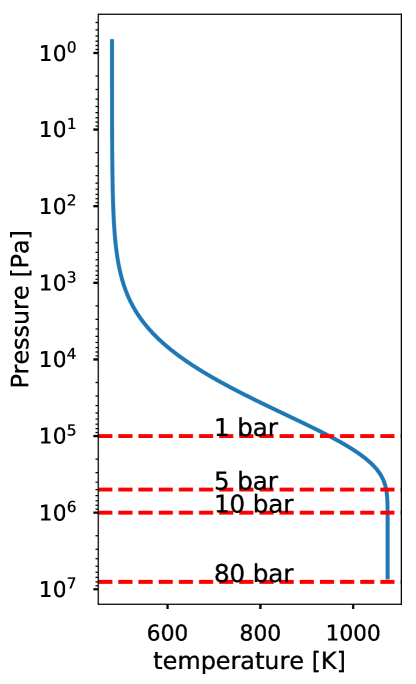

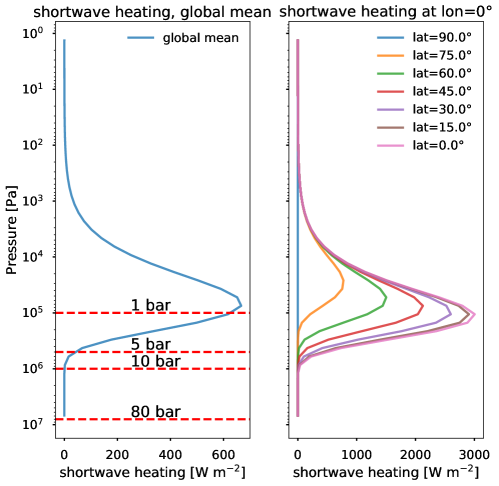

Here and is the mean stellar zenith angle, which is assumed to be the same as the mean infrared propagation angle. Figure 1 is the analytical solution to the 1D gray gas model, with . For the planetary parameters of GJ 1214b, this set of opacity values corresponds to at bar pressure, and at mbar, assuming an optical depth that increases moving downwards into the atmosphere.

In the upper levels of the atmosphere, a sponge layer is applied to reduce spurious reflections of vertically propagating waves. The sponge layer operates as a linear drag on the eddy components of the velocity fields, and does not change the zonal-mean velocities, as described in Forget et al. (1999). The sponge layer term is added to the original , where is a physical field, is the zonal-mean, and is the timescale of the sponge layer. The sponge layer is applied to the three uppermost model levels of three physical fields: zonal velocity, meridional velocity, and potential temperature. is 50,000 s, 100,000 s, and 200,000 s for the highest layer, second highest layer, and third highest layer, respectively.

At the lower boundary, we apply linear Rayleigh drag to represent the drag mechanisms that are believed to limit upper atmospheric wind speeds, such as magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) drag, as discussed in previous literature for exoplanets (Perna et al. (2010), Menou (2012b), Menou (2012a)) and solar system giant planets (Schneider and Liu (2009), Liu and Schneider (2010), Liu et al. (2013)). The Rayleigh drag is applied to the zonal velocity and meridional velocity of the two deepest layers. The timescale of the bottom drag is 20 planet days for the deepest layer, and 40 planet days for the second deepest layer, the same as the values in Menou (2012b). We verified through a series of experiments that the conclusions in this paper are not sensitive to the specific values of or . Below the deepest layer of the atmosphere, we include a surface layer that has relatively low heat capacity and is in radiative balance with the atmosphere. The heat capacity of this surface layer per unit area is J K-1 m-2. For context, this is equivalent to approximately only 0.24 m of well-mixed water on a terrestrial planet such as Earth. The model also includes a convective adjustment scheme (Hourdin et al., 2006). However, as will be discussed in Section 4, convection is not an important effect in our experiments.

We initialize the model with wind velocities of zero and an isothermal temperature of 1000 K, which is close to the radiative equilibrium temperature of a 1D gray gas of the deepest atmosphere (1080 K, as can be found by setting in equation (1)). We tested different initial temperature profiles, including several isothermal temperatures (from 500 to 1400 K) and the radiative equilibrium temperature profile of a 1D gray gas, and found similar final results in all cases. We integrated the model for over 250,000 Earth days, to investigate the convergence time. This corresponded to over eight months of computation time on the Harvard Odyssey supercomputing cluster. The key parameters of our simulations are summarized in Table 1. The experiments with lower bottom boundary pressure (5 and 10 bar instead of 80 bar) are run for 100,000 days, because they reached equilibrium within a shorter time. We have a set of experiments where the lower boundary drag is turned off. The “80 bar without drag” experiment was run for only 150,000 days, because it would have taken us another three months to integrate it to 250,000 days. Table 2 summarizes the integration times, radiative schemes, and bottom layer pressure of previous GCM simulations of GJ 1214b. As can be seen, previous studies simulated the atmosphere of GJ 1214b for between 800 and 7800 days only, with assumed bottom layer pressures of between 10 and 200 bar.

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| planetary radius (m) | |

| gravitational acceleration (m s-2) | 8.93 |

| planetary rotation rate (rad s-1) | |

| bottom boundary pressure (bar) | 5, 10, 80 |

| Atmospheric composition | H2 dominated, solar |

| specific heat at constant pressure (J kg-1 K-1) | 13,000 |

| mean molecular weight (g mol-1) | 2.2 |

| scale height (km) | |

| shortwave gray opacity coefficient () | |

| longwave gray opacity coefficient () | |

| Horizontal resolution | |

| Vertical resolution | |

| Dynamical time step (s) | 90 |

| Radiative time step (s) | 450 |

| Total integration time (Earth days) | 250,000 |

| Note. Parameters for the default run are shown in bold |

| Literature | Integration Time | Radiative Scheme | Bottom Layer Pressure |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Earth days) | (bar) | ||

| This paper | 250,000 | Gray gas | 80 |

| Menou (2012a) | 7800 | Gray gas | 10 |

| Kataria et al. (2014) | 5000 | Correlated- | 200 |

| Charnay et al. (2015a) | 1600 | Correlated- | 80 |

| Drummond et al. (2018) | 800 | Correlated- | 200 |

| Zhang and Showman (2017) | 4000 | Newtonian relaxation | 100 |

| Mayne et al. (2019) | 1000 | Newtonian relaxation | 200 |

3 Results

In this section, we describe our model results. As mentioned in the previous section, we performed three sets of experiments, where the bottom layer pressure was 5 bar, 10 bar and 80 bar respectively. We focus on the 80 bar experiment first.

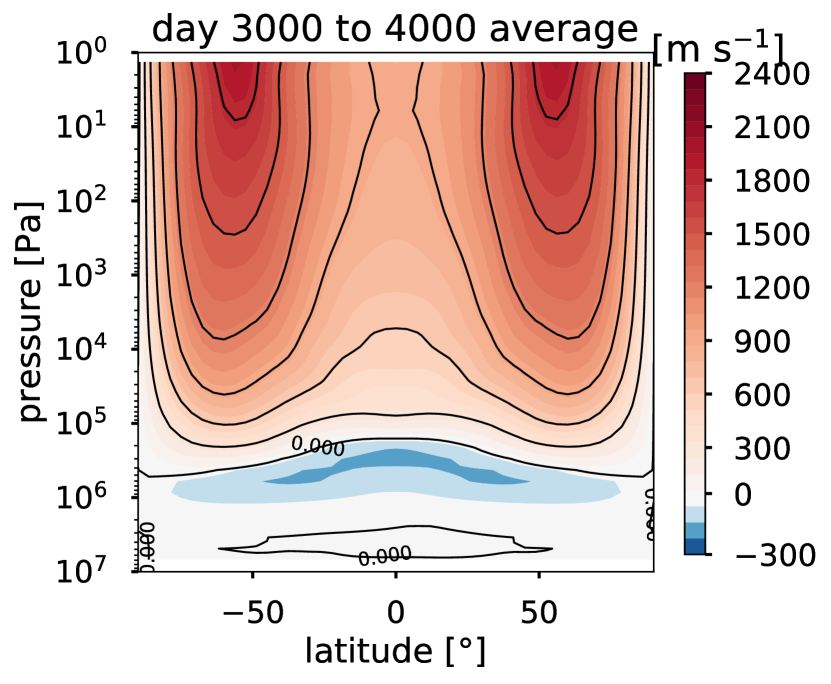

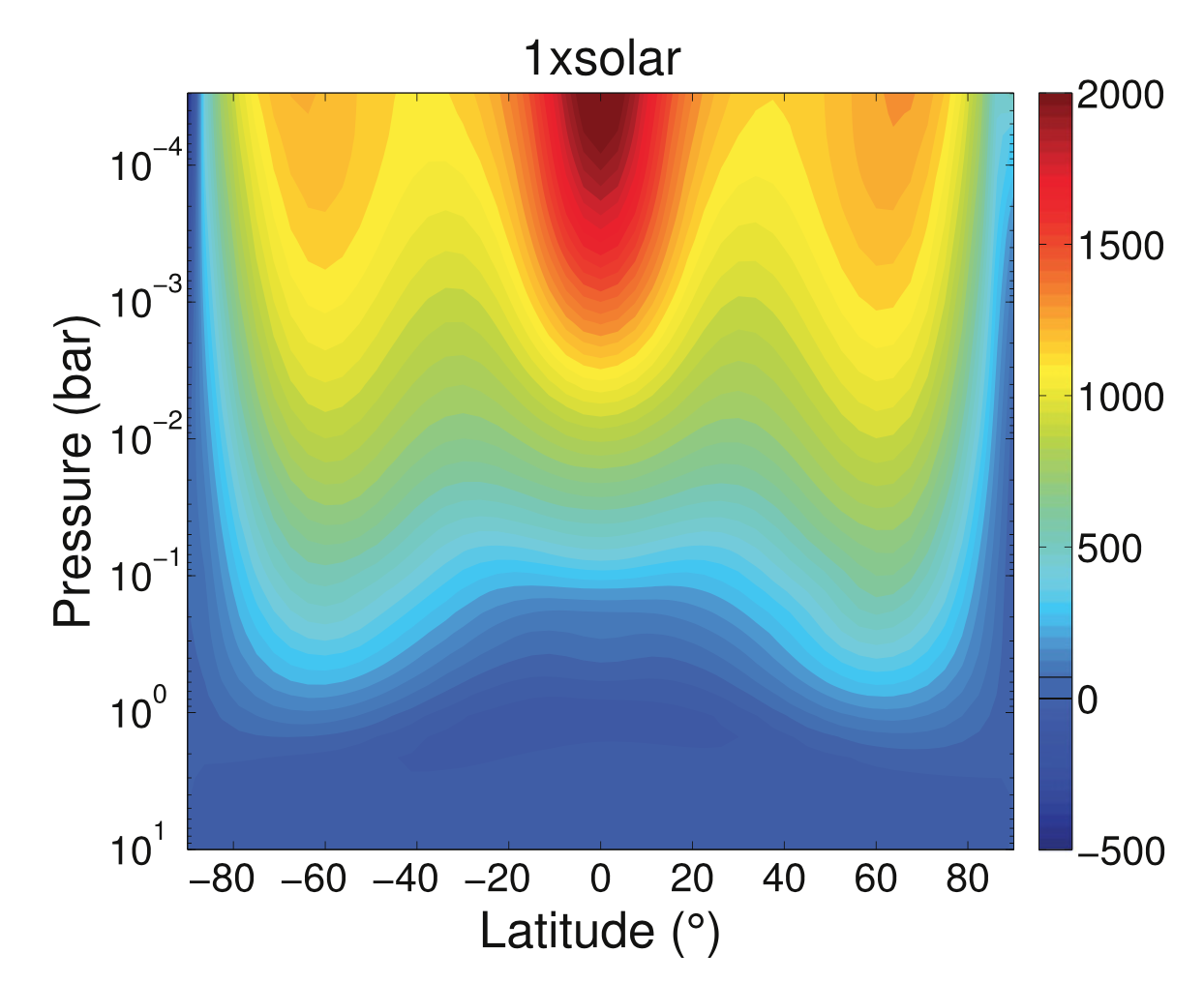

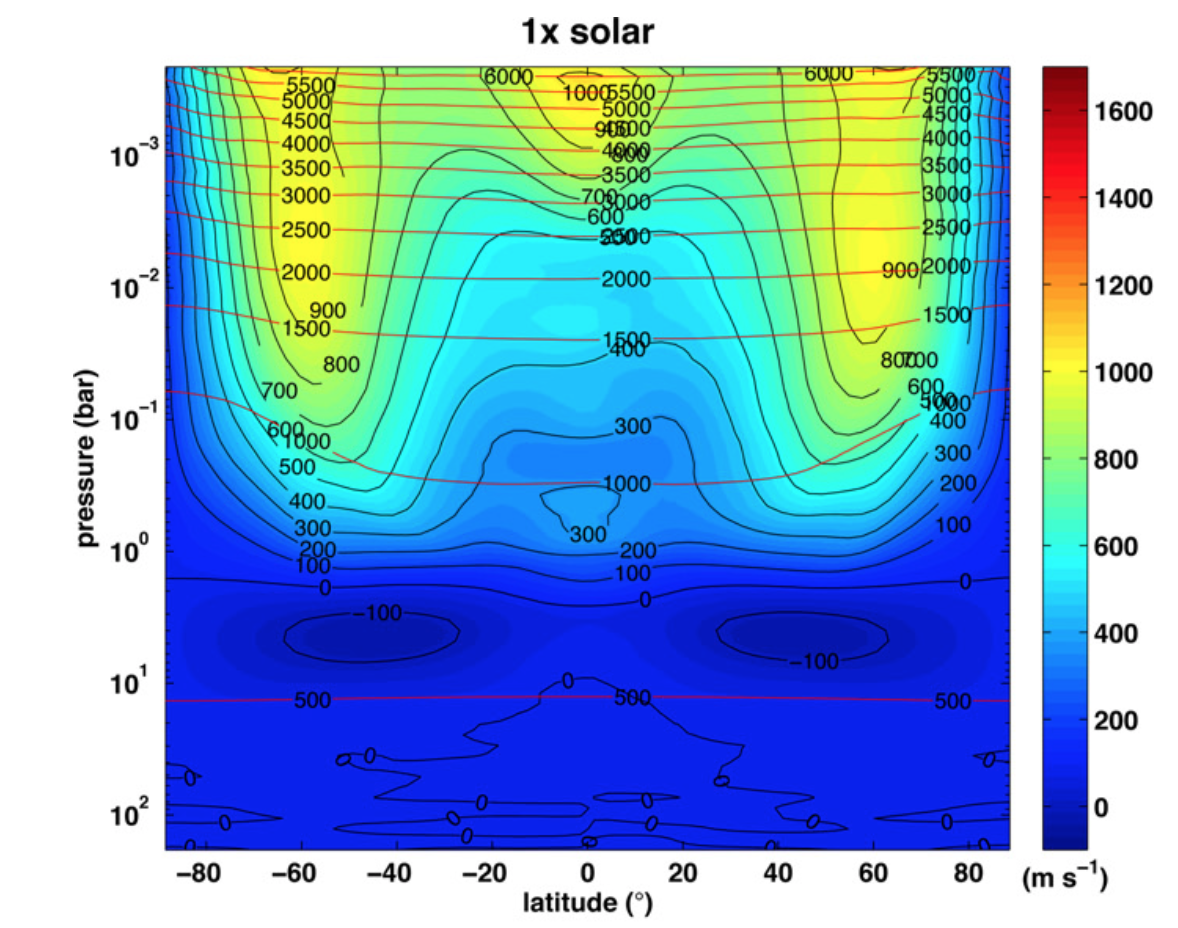

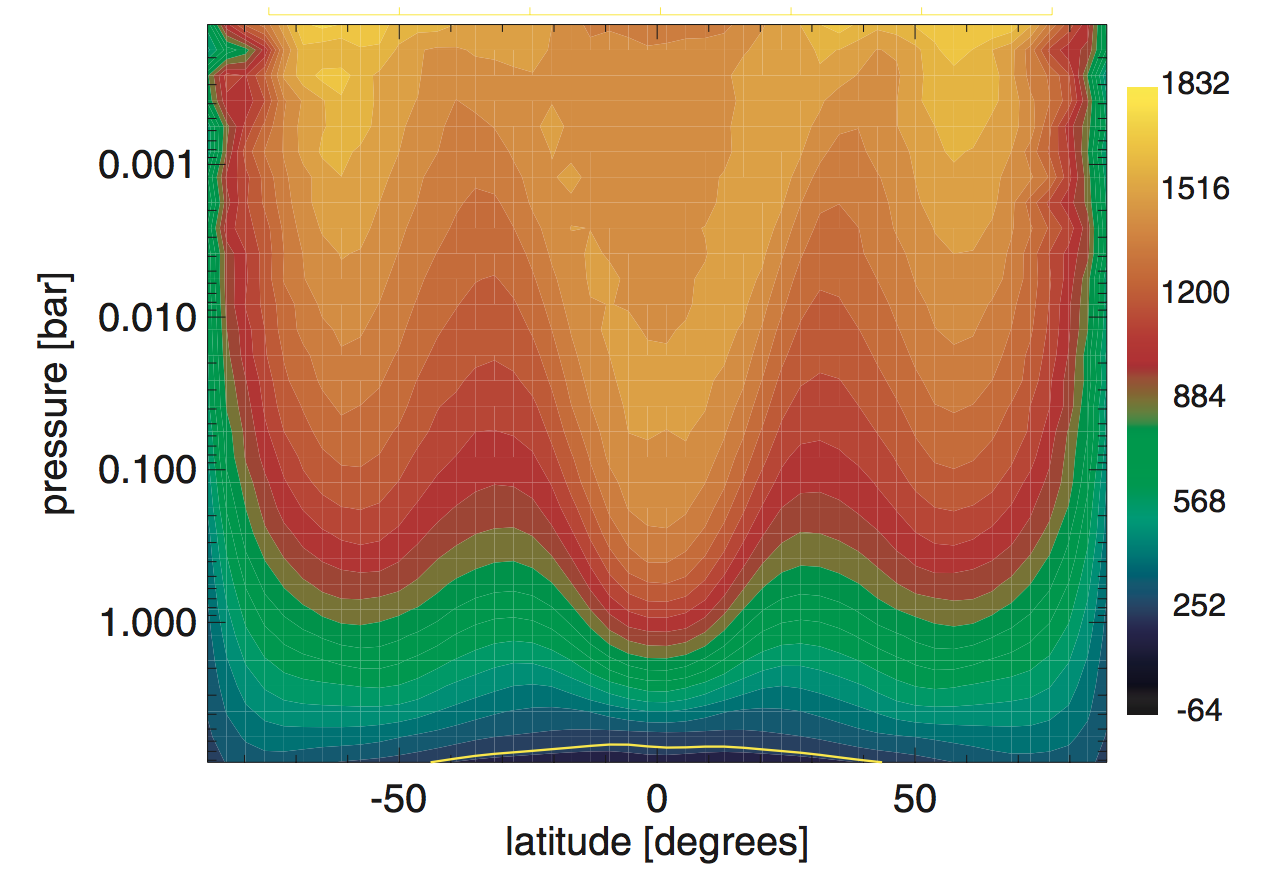

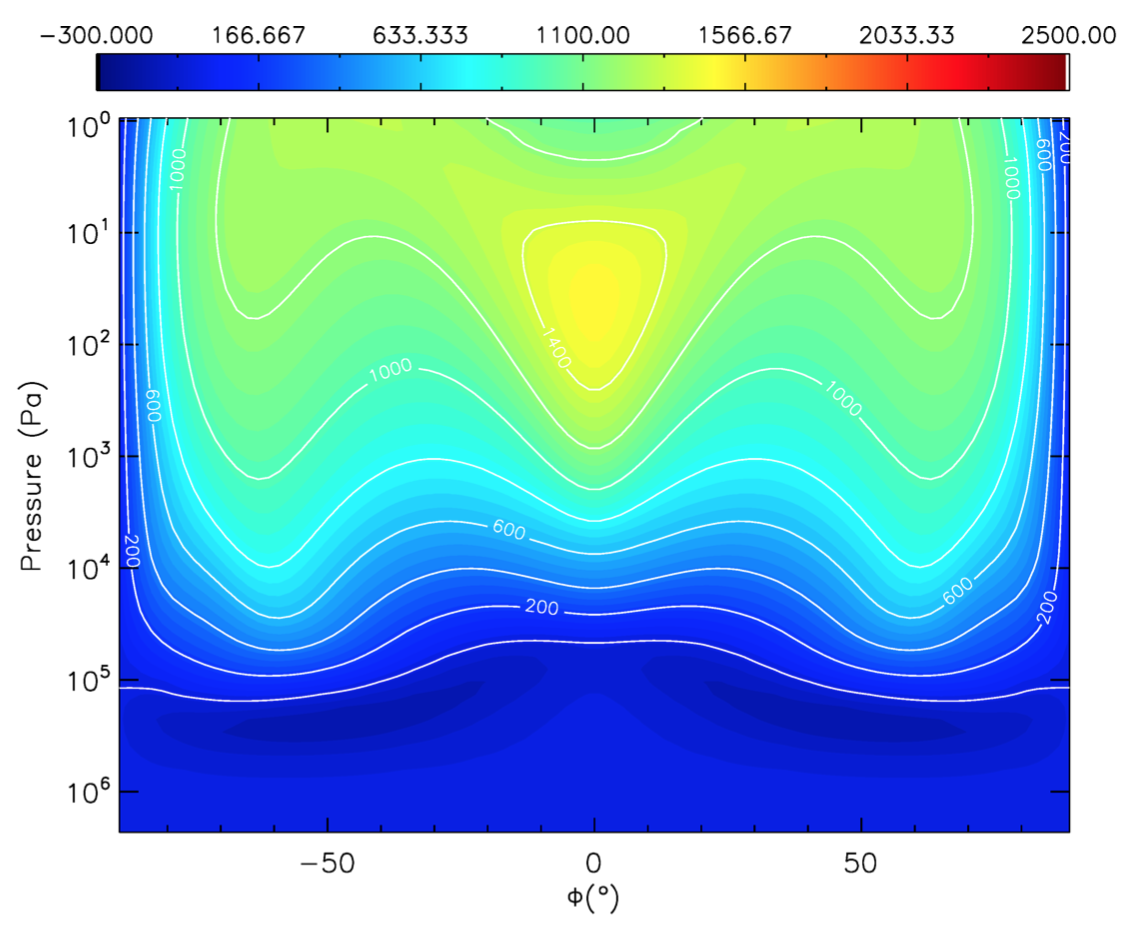

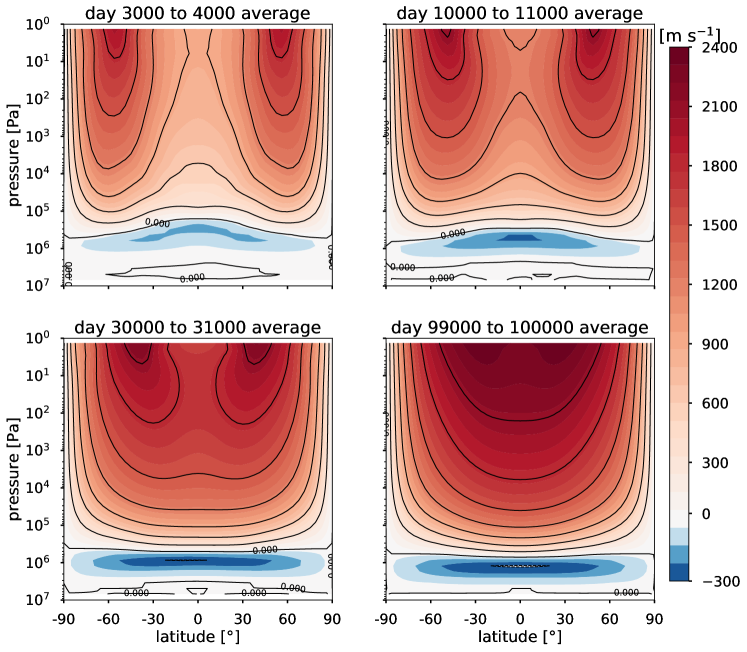

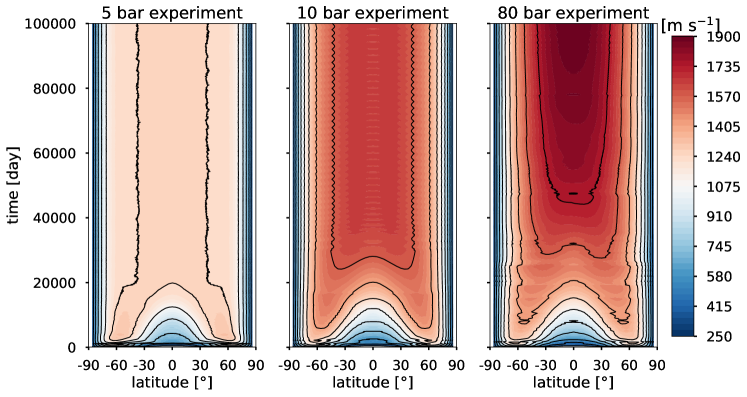

On timescales of 1,000-10,000 Earth days, we find comparable atmospheric features to those found in previous studies, especially that they all exhibit two off-equatorial eastward jets. However, over much longer integration time (50,000-250,000 Earth days), we find different atmospheric dynamical features that have significant observational implications. Previous GCM simulations of GJ 1214b with an H2-dominated atmosphere predicted different zonal-mean zonal velocity profiles (Figure 2). These previous simulations used different GCM models and made different modeling choices, such as in their radiative schemes, as summarized in Table 2. Some of the results show a strong equatorial jet, while some are dominated by two off-equatorial jets, depending on the pressure level of interest.

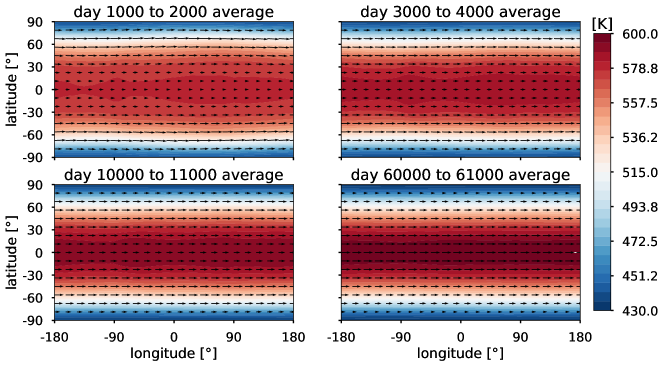

In the upper left panel of Figure 2, we show our simulated zonal-mean zonal velocity profile after integrating our model for 3000-4000 Earth days, which is comparable to the typical integration time of previous studies, in the sense that they are all characterized by two off-equatorial jets. The previous results all have equatorial jets in some regions, but they generally do not extend as deep as the off-equatorial jets. The wind and temperature at 23 mbar, as shown in Figure 3, are very similar to the results of previous studies. The meridional temperature gradient is much greater than the longitudinal one, while the isotherms are not entirely parallel to the x-axis. The wind quivers show two off-equatorial jets. These features are qualitatively identical to the features found in previous studies. As discussed in Showman et al. (2013) and Zhang and Showman (2017), in the regime appropriate to GJ 1214b, the radiative timescale is much longer than the dynamical timescale (wave propagation timescale). As a result, the day-night temperature contrast is weak and the atmospheric flow self-organizes to form a superrotational zonal jet pattern.

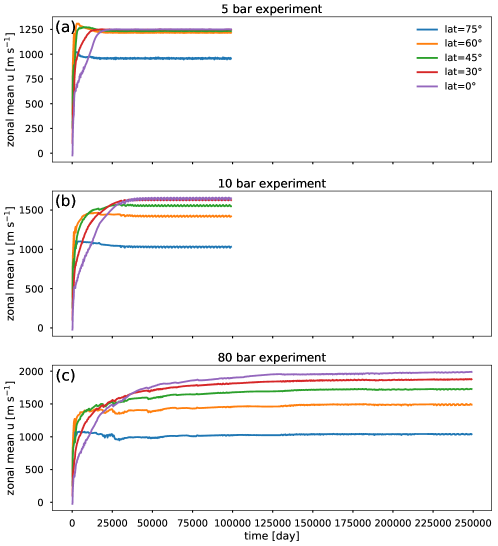

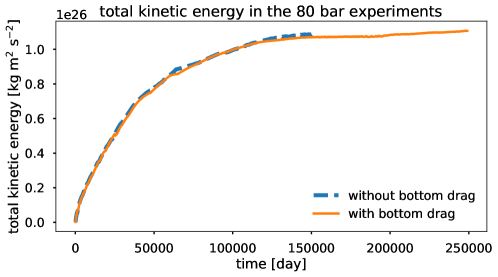

After 4000 days, the zonal flow in our simulations was evolving extremely slowly. However, a persistent secular trend was present. We therefore ran the simulation for another 40,000 Earth days. During this long-term integration, we found that a wide super-rotating jet centered at the equator gradually developed, as shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6. This long convergence timescale can also be seen in the plot of total kinetic energy time series in Figure 7. The continued evolution of the flow features after this long integration time naturally arises from the fact that the deep atmosphere has a long radiative timescale but limited convection.

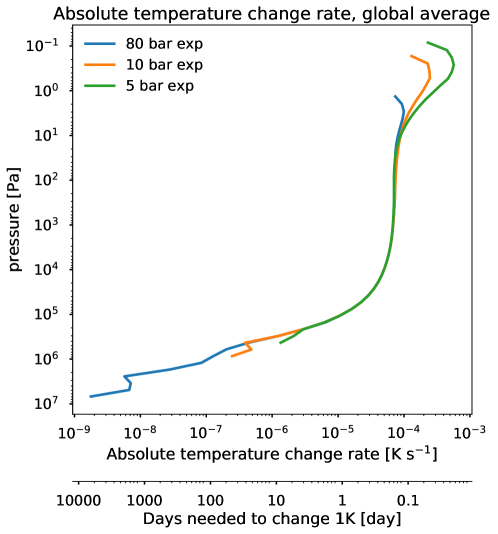

The radiative equilibrium timescale of the deep atmosphere can in principle be estimated by a scaling analysis, but it also depends on the temperature profile of the rest of the atmosphere, making a first-principles approach challenging. Therefore, we take an empirical approach here. In Figure 8, we use GCM diagnostic data and plot the average absolute temperature change rate due to radiative effects, after integrating the model for 50,000 days. We can see that the rate of change of temperature is very small in the deep atmosphere, due to its high mass and optical depth. From Figure 9, we can see that shortwave radiation from the host star is mostly absorbed above the 10 bar level, and the vertical temperature profile deeper than 10 bar level is expected to be very steady. Therefore, the temperature field in the deep atmosphere ( bar) is mainly adjusted by radiative effects, which are extremely slow ( K s-1). We discuss the roles of convection (which was included in our model) and real-gas effects (which were not) in Section 4.

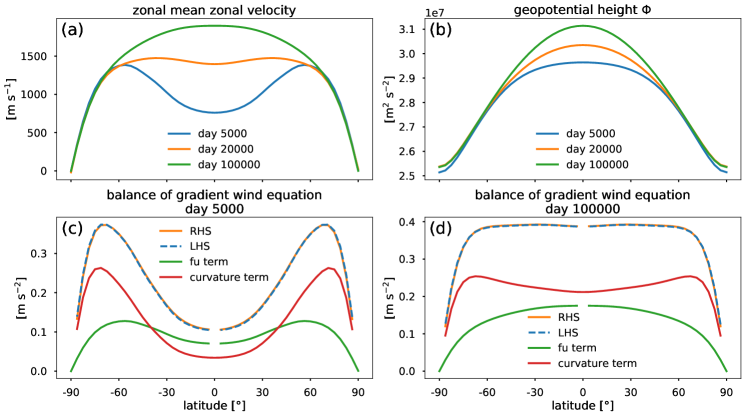

Given the tidally locked forcing pattern, it is natural that the atmosphere develops a meridional temperature gradient with the equator warmer than the poles. Our simulation, like all previous GCM studies, initialized the 3D GCM with horizontally isothermal temperature profiles. Therefore, as the model approaches convergence, a horizontal temperature gradient gradually develops, which takes a long time to form in the deep atmosphere for the reasons discussed above. This meridional gradient of temperature translates into a meridional gradient of geopotential height, which is consistent with the change from two off-equatorial jets to one equatorial jet.

To better illustrate this relationship among the temperature gradient, geopotential height gradient, and zonal jets, we now demonstrate that the flow is in gradient-wind balance by considering the momentum equation of the primitive equations (Vallis, 2006)

| (2) |

where is the material derivative, and are zonal and meridional velocities, is the radius of the planet, is latitude, is the Coriolis parameter, is the angular velocity of the planetary rotation, and is the geopotential height. The geopotential height can be calculated by integrating in the log-pressure vertical coordinate, where is height, is the scale height, and is the gas constant.

Since the radiative timescale is much longer than the dynamical timescale in this case, is much weaker than the other terms (we confirmed this by checking the simulation results). To make the visualization clearer and symmetric about the equator, we can divide equation (2) by , yielding

| (3) |

In Figure 10, we plot the components of equation (3) alongside geopoential height and zonal-mean wind as a function of latitude, for several times in the simulation. As we discussed before, a temperature meridional gradient develops slowly, which in turn increases the meridional gradient of geopotential height at the equator.

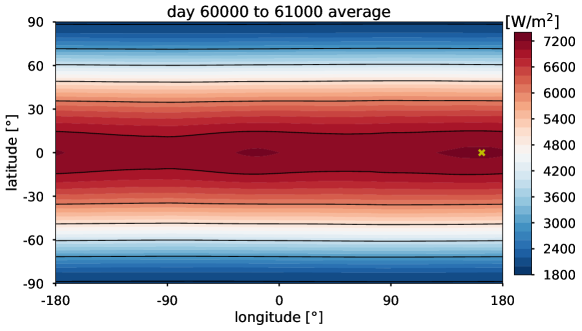

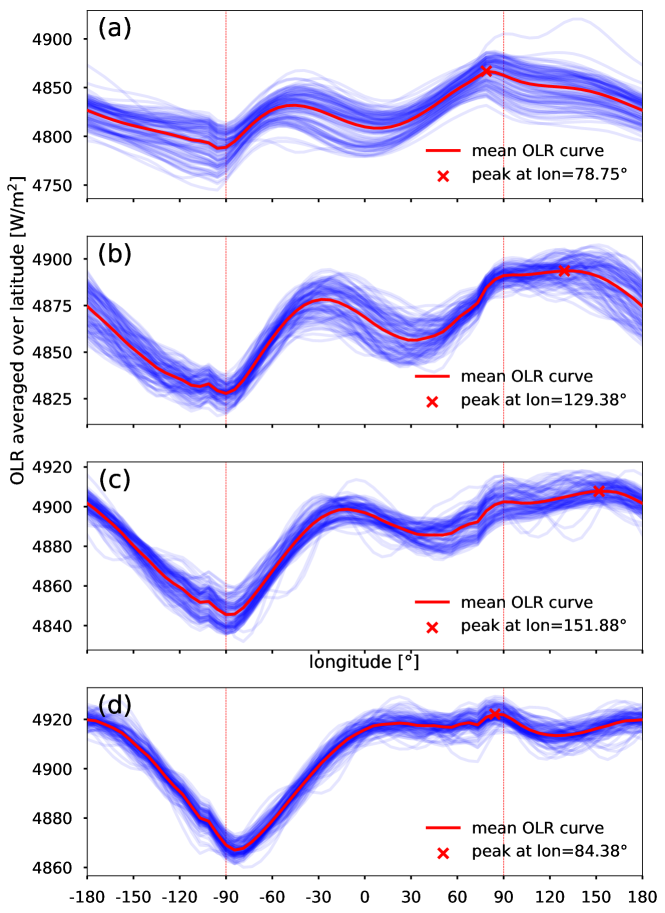

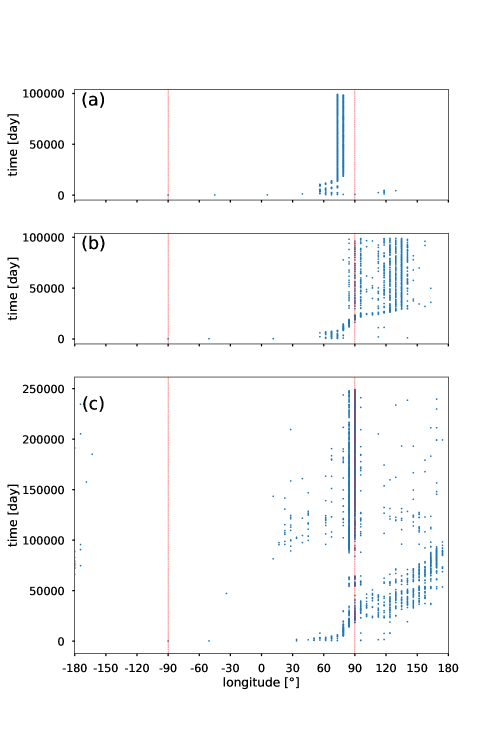

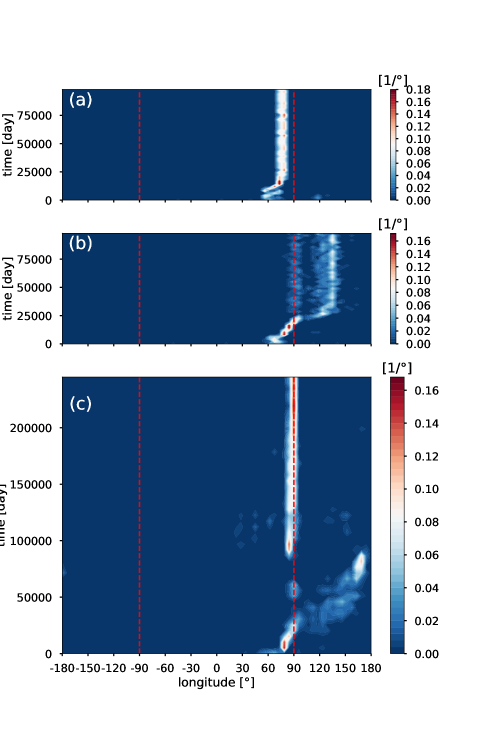

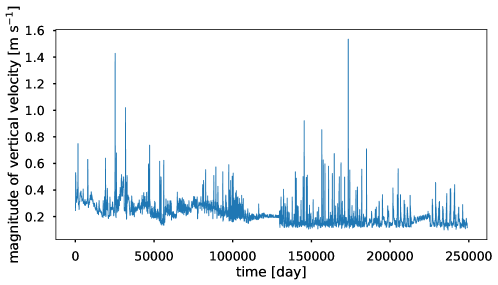

The observational implications of these changes in features are significant. First, as shown in Figure 6, the equatorial jet velocity increased from around 1000 m s-1 to around 2000 m s-1 as we increased the integration time from 10,000 days to 250,000 days. The magnitude of zonal velocity can in principle be directly measured by high-resolution Doppler mapping techniques (i.e. Hot Jupiter HD 209458b Snellen et al. (2010), HD 189733b Louden and Wheatley (2015) and Wyttenbach et al. (2015)). Second, the thermal phase curve becomes flatter because of the increase in zonal velocity over time, as shown in Figure 11 and Figure 12. The locations of the hot spot and the peak in the phase curve also shift eastward between day 25,000 and day 100,000, as plotted in Figure 13 and Figure 14. This is probably also related to the increased zonal velocity and redistribution of heat. Third, as shown in Figure 15, the vertical velocity in the high atmosphere shows strong temporal variability. Given the link between vertical velocity and cloud (e.g., Charnay et al. (2015b)), this result suggests that the high cloud coverage could also be intermittent, which might be observable by studying the temporal variability of a transit spectrum. Future studies can quantify the signal-to-noise ratio of these changes and the detectability given certain planetary parameters and observational instruments.

To show the effect of different choices of bottom layer pressure, we ran a set of comparison experiments, where we set the bottom layer pressure to 1, 5, or 10 bar, respectively. We still have 45 vertical levels spaced in log-pressure, and the two deepest levels included the linear drag as described in Section 2. The 10 bar and 5 bar experiments have qualitatively the same features as the 80 bar standard experiment. In contrast, the 1 bar case does not develop superrotation, and the features are qualitatively very different. Figure 5 and Figure 6 show that the 10 bar experiment and the 5 bar experiment, similar to the default 80 bar experiment, have two off-equatorial jets initially, which then evolve into a single equatorial jet after a longer integration time. The transition time is shorter for lower bottom layer pressure, which is expected because both the total atmospheric mass and the optical depth have decreased. The superrotation velocity is lower when the bottom layer pressure is lower, because the same bottom drag is applied to the deepest two model layers.

The choice of bottom layer pressure also affects the observables. The wind velocities in the upper atmosphere are very different, as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 15. The differences can also be seen in the plots of hot spot location, Figure 13 and Figure 14. In the 5 bar experiment, the hot spot is always on the day side and has weak variability. In the 10 bar experiment, the hot spot started on the day side in the early stage of the experiment, and moved eastward to the night side around day 10,000-day 30,000. In the steady state, the hot spot location jumps between the terminator lines and around longitude 120∘. In the 80 bar experiment, the hot spot location continuously shifts eastward as the system approaches equilibrium, but jumps back to the day side after around day 100,000, which can also be seen in Figure 12(d).

In Figure 4, the deep atmosphere (between 1 and 10 bar) shows a westward jet. Similar features are also seen in previous GCM studies of GJ 1214b, such as Kataria et al. (2014), Charnay et al. (2015a), Menou (2012a) and Drummond et al. (2018). The deep westward jets first appeared as two off-equatorial jets centered at around 40∘-60∘, after 100 days of integration, and were similar to the westward jets in Kataria et al. (2014) and Drummond et al. (2018). After around 1000 days of integration, the two off-equatorial westward jets combined into one jet centered at the equator, which is similar to the flow patterns in Charnay et al. (2015a) and Menou (2012a). We found that switching the bottom layer drag or the top of the atmosphere sponge layer on and off did not change the nature of these westward jets. We tested that these westward jets also appear when the model is initialized with different isothermal temperature profiles (such as 600, 800 and 1200 K). When the lower layer pressure is decreased from 80 bar to 10 bar, the westward jet still develops at the same pressure level. In the 10 bar case, since the lower boundary drag is effectively placed higher in the atmosphere, the westward jet is weaker because of the drag. For the 10 bar experiments without lower boundary drag, the westward jet reaches a similar strength as in the 80 bar case. The results of these tests, together with the fact that similar westward jets appear in previous studies using different GCMs, suggests that these deep westward jets are a physical output of the simulations for the given initial conditions and assumed governing equations rather than a peculiar result of a particular model.

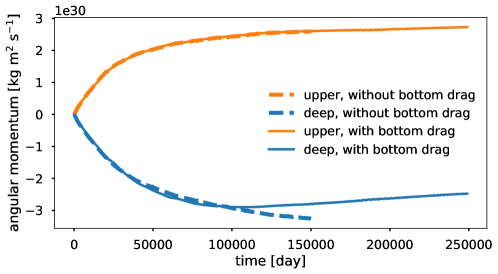

Nonethless, deep jet reversals are not seen in the gas giant planets of the solar System (Kaspi et al., 2018). This is probably because on real planets without an artificially imposed boundary at 5-80 bar, negative angular momentum is able to slowly propagate downward until it eventually becomes indistinguishable from the bulk planetary rotation. In a GCM simulation, in contrast, angular momentum exchange can only occur internally or at the bottom boundary. This can be seen by plotting the total angular momentum of the flow in the top and bottom parts of the atmosphere (Figure 16). As can be seen, angular momentum of the westward jet in the deep atmosphere nearly balances that of the upper atmosphere. The model conservation of angular momentum is not perfect, but it is close considering the extremely long time-scale of the simulation. We also discovered that switching the bottom layer drag on and off did not change the partition of angular momentum in the first 100,000 days. After that the angular momentum lines of bottom drag on/off experiments deviate from each other but only in the lower branch. Our results suggest that angular momentum diagnostics are important, especially for studies of superrotation, and should be routine in exoplanet GCM studies in the future.

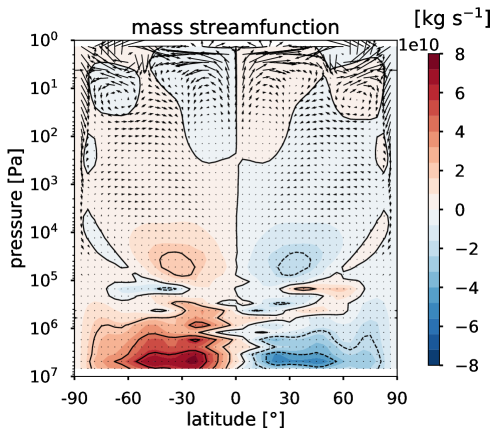

The time-averaged meridional mass streamfunction from 60,000 to 80,000 days is plotted in Figure 17. In the higher atmosphere, the zonally averaged circulation is characterized by a Hadley-like circulation structure driven by upwelling in substellar regions, and reversed circulation cells at higher latitude. In the lower atmosphere, the circulation cells are downwelling at the equator and the upwelling branch extends to higher latitude. These cells may be mechanically driven by the upper-atmosphere circulation. This trend appears to continue to the deepest atmospheric layer in the model, although accumulation of interpolation error in pressure layer and vertical velocity due to our streamfunction integration may have been significant in this region. We hypothesize that momentum exchange between the upper atmosphere and deep atmosphere mainly occurs via vertically propagating eddy potential vorticity fluxes. A detailed exploration of this issue is left to future work.

4 Discussion

Our result is based on modeling a hydrogen-dominated atmosphere of GJ 1214b with a gray gas radiative scheme. However, it may have important implications for studies of hot Jupiter planets in general. Most previous GCM studies of hot Jupiters used temperature-pressure profiles from 1D models to initialize their simulations, where the temperature is assumed to be uniform on every isobaric surface. The integration time of the GCM needs to be long enough for the temperature and wind fields to converge to equilibrium. According to the radiative timescale in Figure 8, integrating the GCM for only a few thousand days is equivalent to expecting the difference between the initial temperature field and the 3D equilibrium state to be within a few kelvin. The 1D models cannot provide information on the horizontal temperature structure, and also lack the 3D dynamics in the GCM that can modify the temperature profile. Since the absorbed stellar radiation has a strong horizontal gradient, a horizontal temperature gradient is also expected for most hot Jupiter regimes, where the dynamical timescale is not significantly shorter than the radiative timescale. Deep atmosphere convergence is critical to allowing an accurate prediction of the upper atmosphere and observables. The radiative timescale in Figure 8 is calculated based on our simulations of GJ 1214b, which is expected to change with planetary parameters, atmospheric compositions, and radiative schemes. For example, Mendonça (2019) found his hot Jupiter simulation converged after 26,500 days of integration, and the hot Jupiter simulations in Mayne et al. (2017) converged in a shorter time.

We therefore believe that future studies of gas exoplanets will benefit from additional attention to a) model convergence and b) angular momentum exchange between the upper atmosphere and the deep interior. As a minimum, longer integration times and careful monitoring of convergence over longer timescales are recommended. Some approaches can potentially shorten the required integration time, such as a more carefully chosen initial temperature field, or using different integration time steps for different levels of the atmosphere. A simple improvement for the initial condition is to use the temperature profile for 3D radiative equilibrium instead of that for 1D radiative equilibrium. Bottom layer pressure and bottom drag are also important modeling choices that require further study.

Convection is not an important effect for our experiments, and turning off the convective adjustment scheme does not change the results or equilibrium timescale. The thermal structure of even a strongly irradiated gas planet with an internal flux does eventually transition to a convection-dominated region in the deep atmosphere. There, the temperature profiles are expected to closely follow the convective adiabat, as discussed in many previous papers, e.g. Hubbard and Smoluchowski (1973), Marley and Robinson (2015), and Robinson and Catling (2012). According to the radiative-convective equilibrium temperature profile calculated in Miller-Ricci and Fortney (2010), for an atmosphere of solar composition on GJ 1214b, the radiative-convective boundary (RCB) where the lapse rate of the atmospheric temperature first decreases from an adiabatic rate to a sub-adiabatic value is deeper than 100 bar. We also confirmed using the gray gas opacities of this paper and 1D radiative-convective model that the RCB is deeper that 100 bar. Note that the height of the RCB depends on the intrinsic temperature, which we assume to be 60 K following structure models of Rogers and Seager (2010). This choice matches the energy equilibrium analysis of Thorngren et al. (2019), which indicated that the RCB should be much deeper than 100 bar given the planetary parameters of GJ 1214b. Since the bottom layer pressure in our experiments is 80 bar, we do not expect convection to be an important effect in our deep atmosphere.

A difference in the convergence time would be expected if our two-band gray gas scheme were changed to a correlated- (Showman et al., 2009; Wordsworth et al., 2011) or even line-by-line radiative scheme (Ding and Wordsworth, 2019). Some spectral bands might have lower absorption coefficients than others, and these “window regions” can change the radiative timescale and the overall convergence timescale. To investigate this possibility, we examined line-by-line absorption coefficients and H2-H2 collision-induced absorption data for a representative atmospheric composition for GJ 1214b (results not shown). We found that unity optical depth in the shortwave occurs around 100 bar for the least opaque wavelength ranges. This is likely an overestimate of the required pressure, because we neglect absorption by important minor species such as H2O. Therefore, even in the real-gas regime, the deeper atmosphere still cannot be effectively heated by shortwave radiation, and will become a convectively stable region with a very long equilibrium timescale. We therefore expect that although the detailed behavior of the jet evolution may vary, the long convergence time we discovered here will still apply to GCM models with correlated- radiative schemes.

In this paper, we were modeling a hydrogen-dominated atmosphere, which is an important scenario for many studies of gas exoplanet. For atmospheric bulk compositions other than hydrogen-dominated ones, we must consider the effects of mean molecular weight () and molar heat capacity at constant pressure (). Given the same bottom level pressure, a greater means the convergence time is shorter. A higher will result in a longer convergence time. As discussed in Zhang and Showman (2017), can vary by a factor of 20, while can only vary by a factor of 4. Therefore, if the bottom level pressure and radiative schemes are the same, we expect the hydro-dominated atmosphere to have the longest convergence timescale among all possible atmospheric compositions.

5 Conclusion

We performed GCM simulations of the exoplanet GJ 1214b and demonstrated that our results resemble previous studies on timescales of 1000-10,000 Earth days, which is the typical integration time of previous GCM studies. Over much longer integration timescales of 50,000 to 250,000 Earth days, we found significantly different flow features. This happened because of the long convergence time in the deep atmosphere, where density is high and radiative timescale is long. The deep atmosphere has a significant impact on the dynamics in the middle and upper atmosphere, as well as on observables such as wind velocity in upper atmosphere, the hot spot location, the thermal phase curve, and potentially cloud coverage.

To properly address the challenge of the long equilibrium timescale of the deep atmosphere for a wider range of exoplanets, further detailed study will be necessary. Conceptually the simplest approach will be to integrate existing models for a longer time and monitor the rate of change of important physical fields, such as temperature and wind velocity. However, it will be important to also consider other model initialization strategies, such as using a 3D radiative equilibrium temperature field, rather than the 1D profile. To reduce computational time, we can also consider reducing the radiative timescale in a physically consistent manner, because the ratio between radiative timescale and dynamical timescale is believed to control important flow patterns such as superrotation (e.g. Zhang and Showman (2017)). Another possibility could be to allow different integration time steps for different layers of the atmosphere, based on, e.g. the approach used in coupled atmosphere-ocean climate modeling (Bryan, 1984). Using different time steps for different levels is not yet supported by standard exoplanet GCMs; a simple version of this idea is similar to the approach used in Earth climate GCMs where an atmosphere model is coupled to a dynamic ocean model. Besides, it will be beneficial to test different characteristic timescales of the bottom boundary drag, which might affect the equilibrium timescale in the deep atmosphere. If the bottom boundary drag is strong enough (characteristic timescale is short enough), or applied to higher in the atmosphere, switching on and off the bottom boundary drag could potentially result in very different steady states. Quantitatively budgeting the conservation of kinetic energy and of angular momentum can also help us understand the long-term behavior of the GCM models. For example, Koll and Komacek (2018) studied the numerical dissipation of energy and angular momentum, which could guide the future setup of numerical drag and parameterized drag.

As pointed out in Section 3 regarding the deep westward jet, the interaction between the artificially imposed lower boundary of the atmosphere and the downward propagation of angular momentum to the very deep atmosphere also requires further study.

This research was supported by NASA Habitable Worlds grant NNX16AR86G and by the Virtual Planetary Laboratory (VPL) program. The GCM simulations in this paper were carried out on the Odyssey cluster supported by the FAS Division of Science, Research Computing Group at Harvard University. The authors would like to thank Feng Ding, Tapio Schneider, Yohai Kaspi, and Wanying Kang for helpful discussions.

References

- Bean et al. (2011) Jacob L Bean, Jean-Michel Désert, Petr Kabath, Brian Stalder, Sara Seager, Eliza Miller-Ricci Kempton, Zachory K Berta, Derek Homeier, Shane Walsh, and Andreas Seifahrt. The optical and near-infrared transmission spectrum of the super-earth gj 1214b: further evidence for a metal-rich atmosphere. The Astrophysical Journal, 743(1):92, 2011.

- Bryan (1984) Kirk Bryan. Accelerating the convergence to equilibrium of ocean-climate models. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 14(4):666–673, 1984.

- Carone et al. (2019) Ludmila Carone, Paul Mollière, Patrick Barth, Allona Vazan, Leen Decin, Paula Sarkis, Olivia Venot, and Thomas Henning. Equatorial anti-rotating day side wind flow in wasp-43b elicited by deep wind jets? arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.13334, 2019.

- Charbonneau et al. (2009) David Charbonneau, Zachory K Berta, Jonathan Irwin, Christopher J Burke, Philip Nutzman, Lars A Buchhave, Christophe Lovis, Xavier Bonfils, David W Latham, Stéphane Udry, et al. A super-earth transiting a nearby low-mass star. Nature, 462(7275):891–894, 2009.

- Charnay et al. (2014) Benjamin Charnay, François Forget, Gabriel Tobie, Christophe Sotin, and Robin Wordsworth. Titan’s past and future: 3d modeling of a pure nitrogen atmosphere and geological implications. Icarus, 241:269–279, 2014.

- Charnay et al. (2015a) Benjamin Charnay, Victoria Meadows, and Jérémy Leconte. 3d modeling of gj1214b’s atmosphere: vertical mixing driven by an anti-hadley circulation. The Astrophysical Journal, 813(1):15, 2015a.

- Charnay et al. (2015b) Benjamin Charnay, Victoria Meadows, Amit Misra, Jérémy Leconte, and Giada Arney. 3d modeling of gj1214b’s atmosphere: formation of inhomogeneous high clouds and observational implications. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 813(1):L1, 2015b.

- Cho et al. (2003) J. Cho, K. Menou, B. Hansen, and S. Seager. The changing face of the extrasolar giant planet hd 209458b. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 587(2):L117, 2003.

- Cho et al. (2015) JY-K Cho, Inna Polichtchouk, and H Th Thrastarson. Sensitivity and variability redux in hot-jupiter flow simulations. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 454(4):3423–3431, 2015.

- Crossfield and Kreidberg (2017) Ian JM Crossfield and Laura Kreidberg. Trends in atmospheric properties of neptune-size exoplanets. arXiv preprint arXiv:1708.00016, 2017.

- Demory et al. (2016) Brice-Olivier Demory, Michael Gillon, Julien de Wit, Nikku Madhusudhan, Emeline Bolmont, Kevin Heng, Tiffany Kataria, Nikole Lewis, Renyu Hu, Jessica Krick, et al. A map of the large day–night temperature gradient of a super-earth exoplanet. Nature, 532(7598):207, 2016.

- Ding and Wordsworth (2019) Feng Ding and Robin D Wordsworth. A new line-by-line general circulation model for simulations of diverse planetary atmospheres: Initial validation and application to the exoplanet gj 1132b. The Astrophysical Journal, 878(2):117, 2019.

- Drummond et al. (2018) Benjamin Drummond, NJ Mayne, Isabelle Baraffe, Pascal Tremblin, James Manners, David S Amundsen, Jayesh Goyal, and David Acreman. The effect of metallicity on the atmospheres of exoplanets with fully coupled 3d hydrodynamics, equilibrium chemistry, and radiative transfer. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 612:A105, 2018.

- Forget et al. (1999) F. Forget, F. Hourdin, R. Fournier, C. Hourdin, O. Talagrand, M. Collins, S. R. Lewis, P. L. Read, and J.-P. Huot. Improved general circulation models of the Martian atmosphere from the surface to above 80 km. Journal of Geophysical Research, 104:24155–24176, 1999.

- Forget et al. (2013) F. Forget, R. D. Wordsworth, E. Millour, J.-B. Madeleine, L. Kerber, J. Leconte, E. Marcq, and R. M. Haberle. 3d modelling of the early martian climate under a denser CO2 atmosphere: Temperatures and CO2 ice clouds. Icarus, 2013.

- Galperin et al. (2004) B. Galperin, H. Nakano, H. Huang, and S. Sukoriansky. The ubiquitous zonal jets in the atmospheres of giant planets and earth’s oceans. Geophysical research letters, 31(13), 2004.

- Hammond and Pierrehumbert (2018) Mark Hammond and Raymond T Pierrehumbert. Wave-mean flow interactions in the atmospheric circulation of tidally locked planets. The Astrophysical Journal, 869(1):65, 2018.

- Heimpel et al. (2005) M. Heimpel, J. Aurnou, and J. Wicht. Simulation of equatorial and high-latitude jets on jupiter in a deep convection model. Nature, 438(7065):193, 2005.

- Heng et al. (2011) K. Heng, K. Menou, and P. J. Phillipps. Atmospheric circulation of tidally locked exoplanets: a suite of benchmark tests for dynamical solvers. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 413(4):2380–2402, 2011.

- Hourdin et al. (2006) F. Hourdin, I. Musat, S. Bony, P. Braconnot, F. Codron, J.-L. Dufresne, L. Fairhead, M.-A. Filiberti, P. Friedlingstein, J.-Y. Grandpeix, G. Krinner, P. Levan, Z.-X. Li, and F. Lott. The LMDZ4 general circulation model: climate performance and sensitivity to parametrized physics with emphasis on tropical convection. Climate Dynamics, 27:787–813, December 2006. 10.1007/s00382-006-0158-0.

- Hubbard and Smoluchowski (1973) William B Hubbard and R Smoluchowski. Structure of jupiter and saturn. Space Science Reviews, 14(5):599–662, 1973.

- Kaspi and Flierl (2007) Y. Kaspi and G. R. Flierl. Formation of jets by baroclinic instability on gas planet atmospheres. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 64(9):3177–3194, 2007.

- Kaspi et al. (2018) Y. Kaspi, E. Galanti, W. B. Hubbard, D. J. Stevenson, S. J. Bolton, L. Iess, T. Guillot, J. Bloxham, J. E. P. Connerney, H. Cao, et al. Jupiter’s atmospheric jet streams extend thousands of kilometres deep. Nature, 555(7695):223, 2018.

- Kataria et al. (2014) Tiffany Kataria, Adam P Showman, Jonathan J Fortney, Mark S Marley, and Richard S Freedman. The atmospheric circulation of the super earth gj 1214b: Dependence on composition and metallicity. The Astrophysical Journal, 785(2):92, 2014.

- Knutson et al. (2007) Heather A Knutson, David Charbonneau, Lori E Allen, Jonathan J Fortney, Eric Agol, Nicolas B Cowan, Adam P Showman, Curtis S Cooper, and S Thomas Megeath. A map of the day–night contrast of the extrasolar planet hd 189733b. Nature, 447(7141):183–186, 2007.

- Knutson et al. (2014) Heather A Knutson, Björn Benneke, Drake Deming, and Derek Homeier. A featureless transmission spectrum for the neptune-mass exoplanet gj 436b. Nature, 505(7481):66, 2014.

- Koll and Komacek (2018) Daniel DB Koll and Thaddeus D Komacek. Atmospheric circulations of hot jupiters as planetary heat engines. The Astrophysical Journal, 853(2):133, 2018.

- Komacek and Showman (2016) Thaddeus D Komacek and Adam P Showman. Atmospheric circulation of hot jupiters: dayside–nightside temperature differences. The Astrophysical Journal, 821(1):16, 2016.

- Kreidberg et al. (2014) Laura Kreidberg, Jacob L Bean, Jean-Michel Désert, Björn Benneke, Drake Deming, Kevin B Stevenson, Sara Seager, Zachory Berta-Thompson, Andreas Seifahrt, and Derek Homeier. Clouds in the atmosphere of the super-earth exoplanet gj1214b. Nature, 505(7481):69–72, 2014.

- Leconte et al. (2013) Jérémy Leconte, Francois Forget, Benjamin Charnay, Robin Wordsworth, and Alizée Pottier. Increased insolation threshold for runaway greenhouse processes on earth-like planets. Nature, 504(7479):268–271, 2013.

- Liu and Showman (2013) Beibei Liu and Adam P Showman. Atmospheric circulation of hot jupiters: insensitivity to initial conditions. The Astrophysical Journal, 770(1):42, 2013.

- Liu and Schneider (2010) J. Liu and T. Schneider. Mechanisms of jet formation on the giant planets. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 67(11):3652–3672, 2010.

- Liu et al. (2013) Junjun Liu, Tapio Schneider, and Yohai Kaspi. Predictions of thermal and gravitational signals of jupiter’s deep zonal winds. Icarus, 224(1):114–125, 2013.

- Louden and Wheatley (2015) Tom Louden and Peter J Wheatley. Spatially resolved eastward winds and rotation of hd 189733b. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 814(2):L24, 2015.

- Marley and Robinson (2015) Mark S Marley and Tyler D Robinson. On the cool side: Modeling the atmospheres of brown dwarfs and giant planets. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 53:279–323, 2015.

- Mayne et al. (2017) Nathan J Mayne, Florian Debras, Isabelle Baraffe, John Thuburn, David S Amundsen, David M Acreman, Chris Smith, Matthew K Browning, James Manners, and Nigel Wood. Results from a set of three-dimensional numerical experiments of a hot jupiter atmosphere. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 604:A79, 2017.

- Mayne et al. (2019) NJ Mayne, B Drummond, F Debras, E Jaupart, J Manners, IA Boutle, I Baraffe, and K Kohary. The limits of the primitive equations of dynamics for warm, slowly rotating small neptunes and super earths. The Astrophysical Journal, 871(1):56, 2019.

- Mendonça (2019) João M Mendonça. Angular momentum and heat transport on tidally locked hot jupiter planets. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.10760, 2019.

- Menou (2012a) Kristen Menou. Atmospheric circulation and composition of gj1214b. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 744(1):L16, 2012a.

- Menou (2012b) Kristen Menou. Magnetic scaling laws for the atmospheres of hot giant exoplanets. The Astrophysical Journal, 745(2):138, 2012b.

- Miller-Ricci and Fortney (2010) Eliza Miller-Ricci and Jonathan J Fortney. The nature of the atmosphere of the transiting super-earth gj 1214b. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 716(1):L74, 2010.

- Perna et al. (2010) Rosalba Perna, Kristen Menou, and Emily Rauscher. Magnetic drag on hot jupiter atmospheric winds. The Astrophysical Journal, 719(2):1421, 2010.

- Pierrehumbert (2011) R.T. Pierrehumbert. Principles of Planetary Climate. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Rauscher and Menou (2012) E. Rauscher and K. Menou. A general circulation model for gaseous exoplanets with double-gray radiative transfer. The Astrophysical Journal, 750(2):96, 2012.

- Read et al. (2007) P. L. Read, Y. H. Yamazaki, S. R. Lewis, P. D. Williams, R. Wordsworth, K. Miki-Yamazaki, J. Sommeria, and H. Didelle. Dynamics of convectively driven banded jets in the laboratory. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 64(11):4031–4052, 2007.

- Robinson and Catling (2012) Tyler D Robinson and David C Catling. An analytic radiative-convective model for planetary atmospheres. The Astrophysical Journal, 757(1):104, 2012.

- Rogers and Seager (2010) LA Rogers and Sara Seager. Three possible origins for the gas layer on gj 1214b. The Astrophysical Journal, 716(2):1208, 2010.

- Schneider and Liu (2009) T. Schneider and J. Liu. Formation of jets and equatorial superrotation on jupiter. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 66(3):579–601, 2009.

- Seager and Deming (2010) Sara Seager and Drake Deming. Exoplanet atmospheres. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 48:631–672, 2010.

- Showman and Polvani (2011) Adam P Showman and Lorenzo M Polvani. Equatorial superrotation on tidally locked exoplanets. The Astrophysical Journal, 738(1):71, 2011.

- Showman et al. (2009) Adam P Showman, Jonathan J Fortney, Yuan Lian, Mark S Marley, Richard S Freedman, Heather A Knutson, and David Charbonneau. Atmospheric circulation of hot jupiters: Coupled radiative-dynamical general circulation model simulations of hd 189733b and hd 209458b. The Astrophysical Journal, 699(1):564, 2009.

- Showman et al. (2012) Adam P Showman, Jonathan J Fortney, Nikole K Lewis, and Megan Shabram. Doppler signatures of the atmospheric circulation on hot jupiters. The Astrophysical Journal, 762(1):24, 2012.

- Showman et al. (2013) Adam P Showman, Robin D Wordsworth, Timothy M Merlis, and Yohai Kaspi. Atmospheric circulation of terrestrial exoplanets. arXiv preprint arXiv:1306.2418, 2013.

- Snellen et al. (2010) Ignas AG Snellen, Remco J de Kok, Ernst JW de Mooij, and Simon Albrecht. The orbital motion, absolute mass and high-altitude winds of exoplanet hd [thinsp] 209458b. Nature, 465(7301):1049–1051, 2010.

- Thorngren et al. (2019) Daniel P Thorngren, Peter Gao, and Jonathan J Fortney. The intrinsic temperature and radiative-convective boundary depth in the atmospheres of hot jupiters. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.07777, 2019.

- Tsai et al. (2014) Shang-Min Tsai, Ian Dobbs-Dixon, and Pin-Gao Gu. Three-dimensional structures of equatorial waves and the resulting super-rotation in the atmosphere of a tidally locked hot jupiter. The Astrophysical Journal, 793(2):141, 2014.

- Vallis (2006) Geoffrey K Vallis. Atmospheric and oceanic fluid dynamics: fundamentals and large-scale circulation. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Wordsworth et al. (2013) R Wordsworth, F Forget, E Millour, JW Head, J-B Madeleine, and B Charnay. Global modelling of the early martian climate under a denser co2 atmosphere: Water cycle and ice evolution. Icarus, 222(1):1–19, 2013.

- Wordsworth et al. (2011) R. D. Wordsworth, F. Forget, F. Selsis, E. Millour, B. Charnay, and J.-B. Madeleine. Gliese 581d is the First Discovered Terrestrial-mass Exoplanet in the Habitable Zone. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 733:L48, June 2011. 10.1088/2041-8205/733/2/L48.

- Wyttenbach et al. (2015) Aurélien Wyttenbach, D Ehrenreich, C Lovis, S Udry, and F Pepe. Spectrally resolved detection of sodium in the atmosphere of hd 189733b with the harps spectrograph. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 577:A62, 2015.

- Young et al. (2019) Roland MB Young, Peter L Read, and Yixiong Wang. Simulating jupiter’s weather layer. part i: Jet spin-up in a dry atmosphere. Icarus, 326:225–252, 2019.

- Zalucha et al. (2013) Angela M Zalucha, Timothy I Michaels, and Nikku Madhusudhan. An investigation of a super-earth exoplanet with a greenhouse-gas atmosphere using a general circulation model. Icarus, 226(2):1743–1761, 2013.

- Zellem et al. (2014) Robert T Zellem, Nikole K Lewis, Heather A Knutson, Caitlin A Griffith, Adam P Showman, Jonathan J Fortney, Nicolas B Cowan, Eric Agol, Adam Burrows, David Charbonneau, et al. The 4.5 m full-orbit phase curve of the hot jupiter hd 209458b. The Astrophysical Journal, 790(1):53, 2014.

- Zhang and Showman (2017) Xi Zhang and Adam P Showman. Effects of bulk composition on the atmospheric dynamics on close-in exoplanets. The Astrophysical Journal, 836(1):73, 2017.