Force Dependent Hopping Rates of RNA Hairpins can be Estimated from Accurate Measurement of the Folding Landscapes

Abstract

The sequence-dependent folding landscapes of nucleic acid hairpins reflect much of the complexity of biomolecular folding. Folding trajectories, generated using single molecule force clamp experiments by attaching semiflexible polymers to the ends of hairpins have been used to infer their folding landscapes. Using simulations and theory, we study the effect of the dynamics of the attached handles on the handle-free RNA free energy profile , where is the molecular extension of the hairpin. Accurate measurements of requires stiff polymers with small , where is the contour length of the handle, and is the persistence length. Paradoxically, reliable estimates of the hopping rates can only be made using flexible handles. Nevertheless, we show that the equilibrium free energy profile at an external tension , the force () at which the folded and unfolded states are equally populated, in conjunction with Kramers’ theory, can provide accurate estimates of the force-dependent hopping rates in the absence of handles at arbitrary values of . Our theoretical framework shows that is a good reaction coordinate for nucleic acid hairpins under tension.

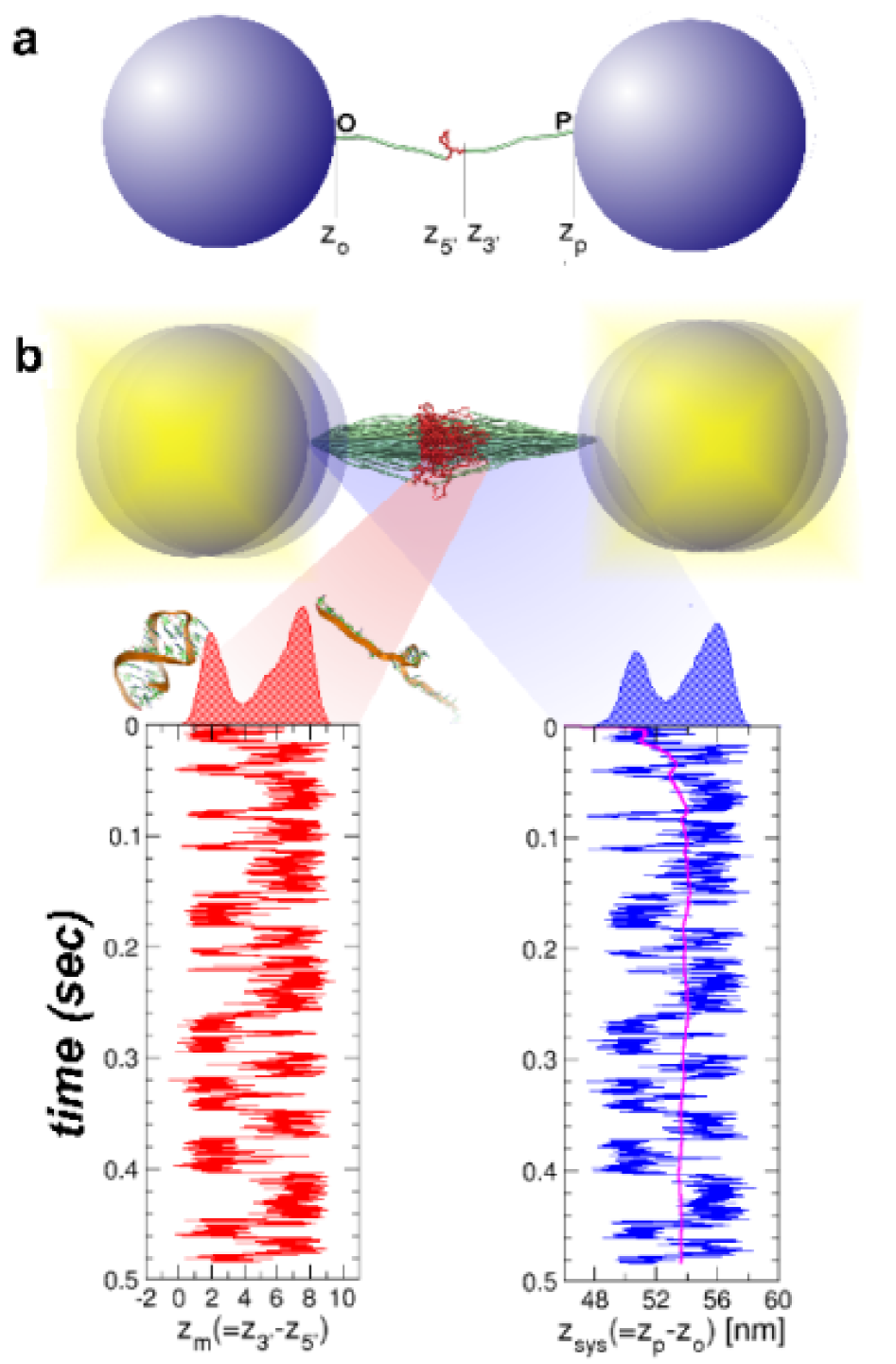

A molecular understanding of how proteins and RNA fold is needed to describe the functions of enzymes FershtBook and ribozymes DoudnaNature02 , interactions between biomolecules, and the origins of misfolding that is linked to a number of diseases Dobson99TBS . The energy landscape perspective has provided a conceptual framework for describing the mechanisms by which unfolded molecules navigate the large conformational space in search of the native state DillNSB97 ; OnuchicCOSB04 ; HyeonBC05 . Recently, single molecule techniques have been used to probe features of the energy landscape of proteins and RNA that are not easily accessible in ensemble experiments Fisher00NSB ; Bustamante01Science ; Haran03PNAS ; TinocoBJ06 ; SchulerNATURE2002 ; ZhuangCOSB03 ; EvansNature99 ; Woodside06PNAS ; Block06Science ; Li07PNAS ; DietzPNAS04 ; Mickler07PNAS . It is possible to construct the shape of the energy landscape, including the energy scales of ruggedness HyeonPNAS03 ; ReichEMBOrep05 , using dynamical trajectories that are generated by applying a constant force () to the ends of proteins and RNA Schlierf04PNAS ; Woodside06PNAS ; Fernandez06NaturePhysics ; Block06Science . If the observation time is long enough for the molecule to sample the accessible conformational space, then the time average of an observable recorded for the molecule () should equal the ensemble average (), and the distribution should converge to the equilibrium distribution function . Using this strategy, laser optical tweezer (LOT) experiments have been used to obtain the sequence-dependent folding landscape of a number of RNA and DNA hairpins Bustamante01Science ; Woodside06PNAS ; Bustamante03Science ; Block06Science , using , the end-to-end distance of the hairpin that is conjugate to , as a natural reaction coordinate. In LOT experiments, the hairpin is held between two long handles (DNA Block06Science or DNA/RNA hybrids Bustamante01Science ), whose ends are attached to polystyrene beads (Fig. 1a). The equilibrium free energy profile (, is the Boltzmann constant, and is the absolute temperature) may be useful in describing the dynamics of the molecule, provided is an appropriate reaction coordinate.

The dynamics of the RNA extension in the presence of (, provided transverse fluctuations are small) is indirectly obtained in an LOT experiment by monitoring the distance between the attached polystyrene beads (), one of which is optically trapped at the center of the laser focus (Fig 1a). The goal of these experiments is to extract the folding landscape () and the dynamics of the hairpin in the absence of handles, using the -dependent trajectories . To achieve these goals, the fluctuations in the handles should minimally perturb the dynamics of the hairpin in order to probe the true dynamics of a molecule of interest. However, depending on and ( is the contour length of the handle and is its persistence length), the intrinsic fluctuations of the handles can not only disort the signal from the hairpin, but also directly affect its dynamics. The first is a problem that pertains to the measurement process, while the second is a problem of the coupling between the instruments and the dynamics of RNA.

Here, we use coarse-grained molecular simulations of RNA hairpin and theory to show that, in order to obtain accurate , the linkers used in the LOT have to be stiff, i.e., the value of has to be small. To investigate the handle effects on the energy landscape and hopping kinetics, we simulated the

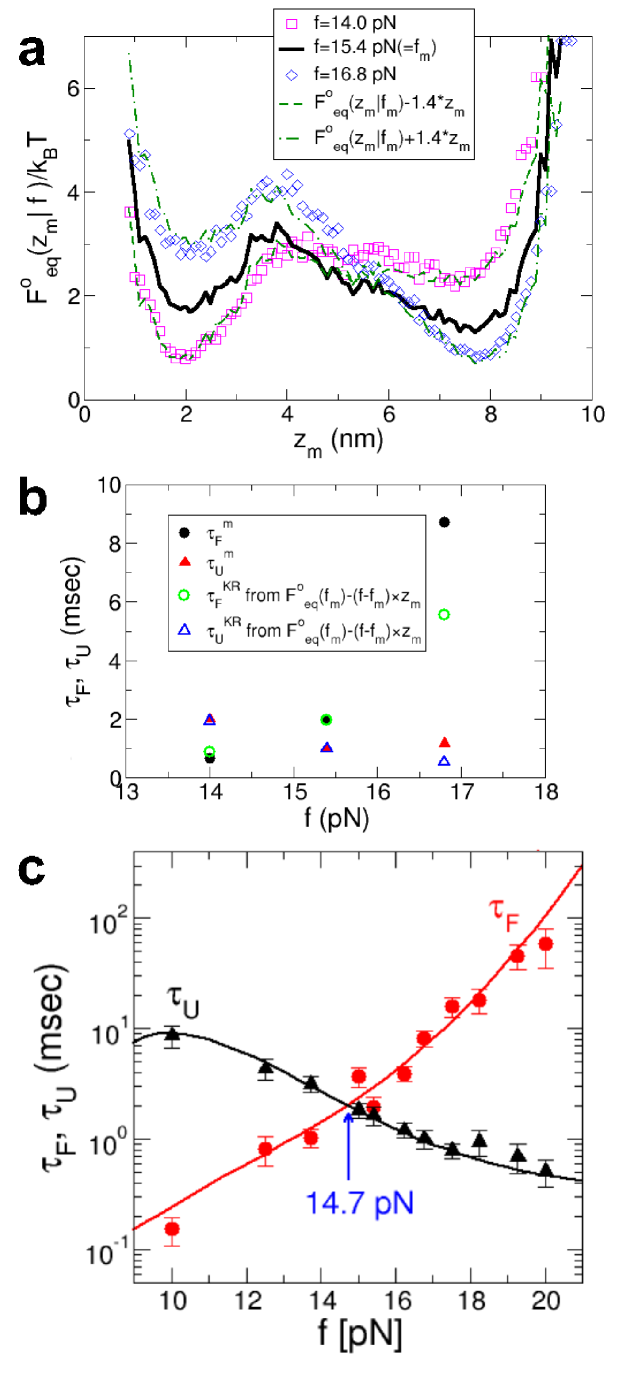

hairpin dynamics under force-clamp conditions by explicitly modeling the linkers as polymers with varying and . Surprisingly, the force-dependent folding and unfolding rates that are directly measured using the time traces, , are close to the ideal values (those that are obtained by directly applying , without the handles, to the 3’ end with a fixed 5’ end) only when the handles are flexible. Most importantly, accurate estimates of the -dependent hopping rates over a wide range of -values, in the absence of handles, can be made using , in the presence of handles obtained at , the transition midpoint at which the native basin of attraction (NBA) and the unfolded basin of attraction (UBA) of the RNA are equally populated. The physics of a hairpin attached to handles is captured using a generalized Rouse model (GRM), in which there is a favorable interaction between the two non-covalently linked ends. The GRM gives quantitative agreement with the simulation results. The key results announced here provide a framework for using the measured folding landscape of nucleic acid hairpins at to obtain -dependent folding and unfolding times and the transition state movements as is varied KlimovPNAS99 ; HyeonPNAS05 ; RitortPRL06 ; West06BJ ; Dudko06PRL ; Hyeon07JP .

RESULTS and DISCUSSIONS

Modeling the LOT experiments: In order to extract the folding landscape from LOT experiments, the time scales associated with the dynamics of the beads, handles, and the hairpin have to be well-separated RitortBJ05 ; HyeonBJ06 ; Manosas07BJ ; WestPRE . The bead fluctuations are described by the overdamped Langevin equation where is the spring constant associated with the restoring force, and the random white-noise force satisfies and . The bead relaxes to its equilibrium position on a time scale . In terms of the trap stiffness, , and the stiffness associated with the Handle-RNA-Handle (H-RNA-H; see Fig. 1), . With , m, cP, pN/nm Block94ARBBS , and pN/nm, we find ms. In LOT experiments RitortBJ05 ; Manosas07BJ ; WestPRE , separation in time scales is satisfied such that at , where and are the intrinsic values of the RNA (un)folding times in the absence of handles.

Since is a natural reaction coordinate in force experiments, the dispersion of the bead position may affect the measurement of . At equilibrium, the fluctuations in the bead positions satisfy , and hence should be large enough to minimize the dispersion of the bead position. The force fluctuation, , is negligible in the LOT because , and as a result , since pN while pN. Thus, we model the LOT setup by assuming that the force and position fluctuations due to the bead are small, and exclusively focus on the effect of handle dynamics on the folding landscape and hopping kinetics of RNA (Figs. 1a-b).

Short, stiff handles are required for accurate free energy profiles: For purposes of illustration, we used the self-organized polymer (SOP) model of the P5GA hairpin HyeonBJ07 , and applied a force pN. The force is exerted on the end of the handle attached to the 3’ end of the RNA (P in Fig.1a), while fixing the other end (O in Fig.1a). Simulations of P5GA with handles of length nm and persistence length nm show that the extension of the entire system () fluctuates between two limits centered around nm and nm (Fig. 1b). The time-dependent transitions in between 50 nm and 56 nm correspond to the hopping of the RNA between the Native Basin of Attraction (NBA) and Unfolded Basin of Attraction (UBA). Decomposition of as , where and are the extensions of the handles parallel to the force direction (Fig. 1a), shows that reflects the transitions in (Fig. 1b). Because the simulation time is long enough for the harpin to ergodically explore the conformations between the NBA and UBA, the histograms collected from the time traces amount to the equilibrium distributions where , , , or (Fig 1b; for and , see the Supporting Information SI Fig. 6a). To establish that the time traces are ergodic, we show that reaches the thermodynamic average ( =53.7 nm) after sec (the magenta line on in Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1b shows that the positions of the handles along the direction fluctuate, even in the presence of tension, which results in slight differences between and . Comparison between the free energy profiles obtained from the and can be used to investigate the effect of the characteristics of the handles on the free energy landscape.

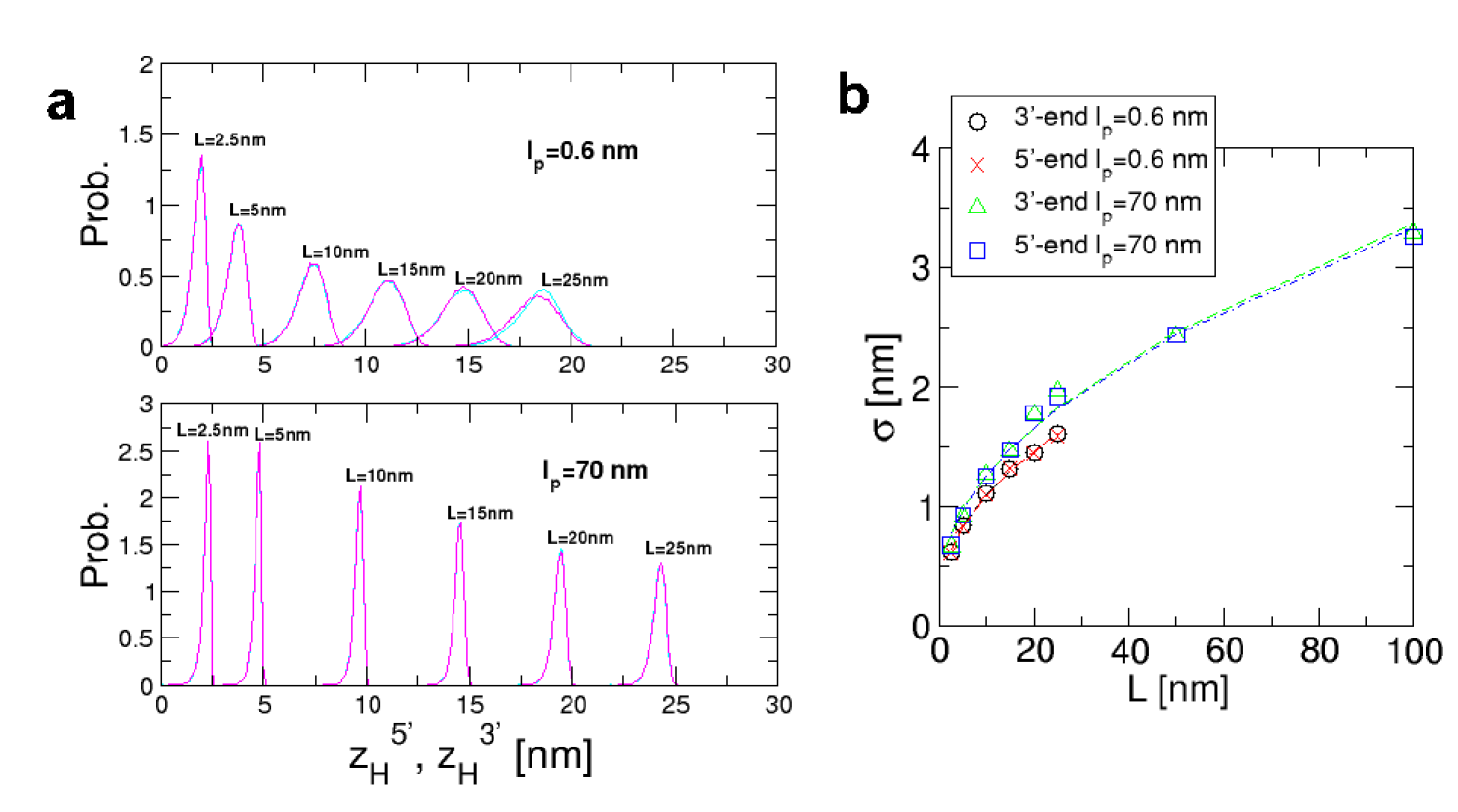

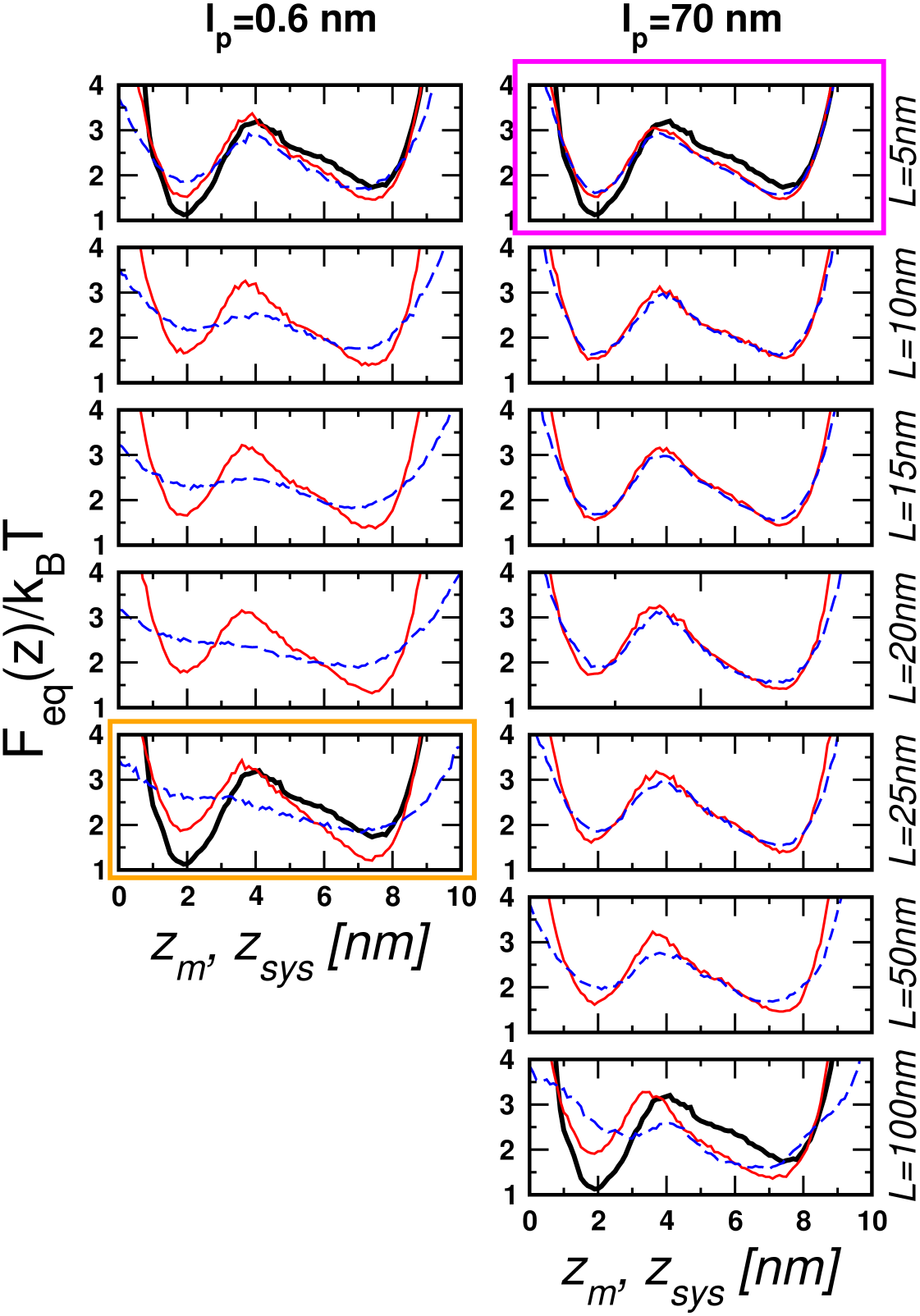

To this end, we repeated the force-clamp simulations by varying the contour length ( nm) and persistence length ( and 70 nm) of the handles.

Fig. 2 shows that the discrepancy between the measured free energy (dashed lines in blue) and the molecular free energy (solid lines in red) increases for the more flexible and longer handles (see the SI text and SI Fig. 6 for further discussion of the dependence of the handle fluctuations on and ). For small and large , the basins of attraction in are not well resolved. The largest deviation between and is found when nm and nm () (the graph enclosed by the orange box in Fig. 2a).

In contrast, the best agreement between and is found for nm and nm (the graph inside the magenta box in Fig. 2), which corresponds to .

In the LOT experiments, Bustamante01Science ; Woodside06PNAS ; Block06Science .

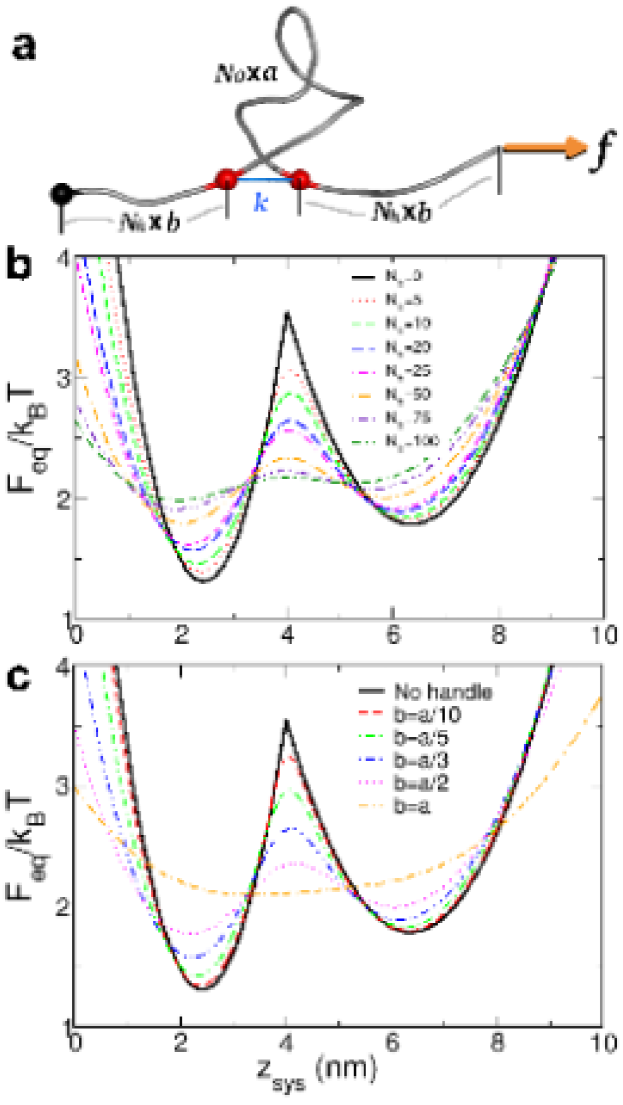

Generalized Rouse model (GRM) captures the physics of H-RNA-H under tension: In order to establish the generality of the relationship between the free energy profiles as measured by and those measured by , we introduce an exactly solvable model that minimally represents the RNA and handles (Fig. 3a). We mimic the hairpin using a Gaussian chain with monomers and Kuhn length . The endpoints of the RNA mimic are harmonically trapped in a potential with stiffness as long as they are within a cutoff distance nm. Two handles, each with monomers and Kuhn length , are attached to the ends of the RNA (see Methods). We fix one endpoint of the entire chain at the origin, and apply a force pN to the other end. The free energies as a function of both the RNA’s extension, ( at high ) and the system’s extension ( at high ) are exactly solvable in the continuum representation. We choose such that is near the midpoint of the transition, so that . We tune so that the barrier heights for the GRM and P5GA are similar at . These requirements give and pN/nm.

While the stiffness in the handles of the simulated system (Fig. 1) cannot be accurately modeled using a Gaussian chain, the primary effect of attaching the handles is to alter the fluctuations of the endpoints of the RNA. By equating the longitudinal fluctuations for the WLC, , with the fluctuations for the Gaussian handles, , we estimate that the effective persistence length of the handles scales as (see the SI for details).

Thus, smaller spacing in the Gaussian handles in the GRM will mimic stiffer handles in the H-RNA-H system. The free energies computed for the GRM, shown in Fig. 3b-c, are consistent with the results of the simulations. The free energy profiles deviate significantly from as increases or ‘stiffness’ decreases. The relevant variable that determines the accuracy of is , with the free energies remaining unchanged if is kept constant. The barrier height and well depths as a function of are unchanged as a function of and . However, the apparent activation energy is decreased as measured by (seen in Fig. 2 as well). The GRM confirms that accurate measurement of the folding landscape using requires stiff handles.

Accurate estimates of the hopping kinetics requires short and flexible handles: Because LOT experiments can also be used to measure the force-dependent rates of hopping between the NBA and the UBA, it is important to assess the influence of the dynamics of the handles on the intrinsic hopping kinetics of the RNA hairpin. In other words, how should the structural characteristics of the linkers be chosen so that the measured hopping rates using the time traces and the intrinsic rates are as close as possible?

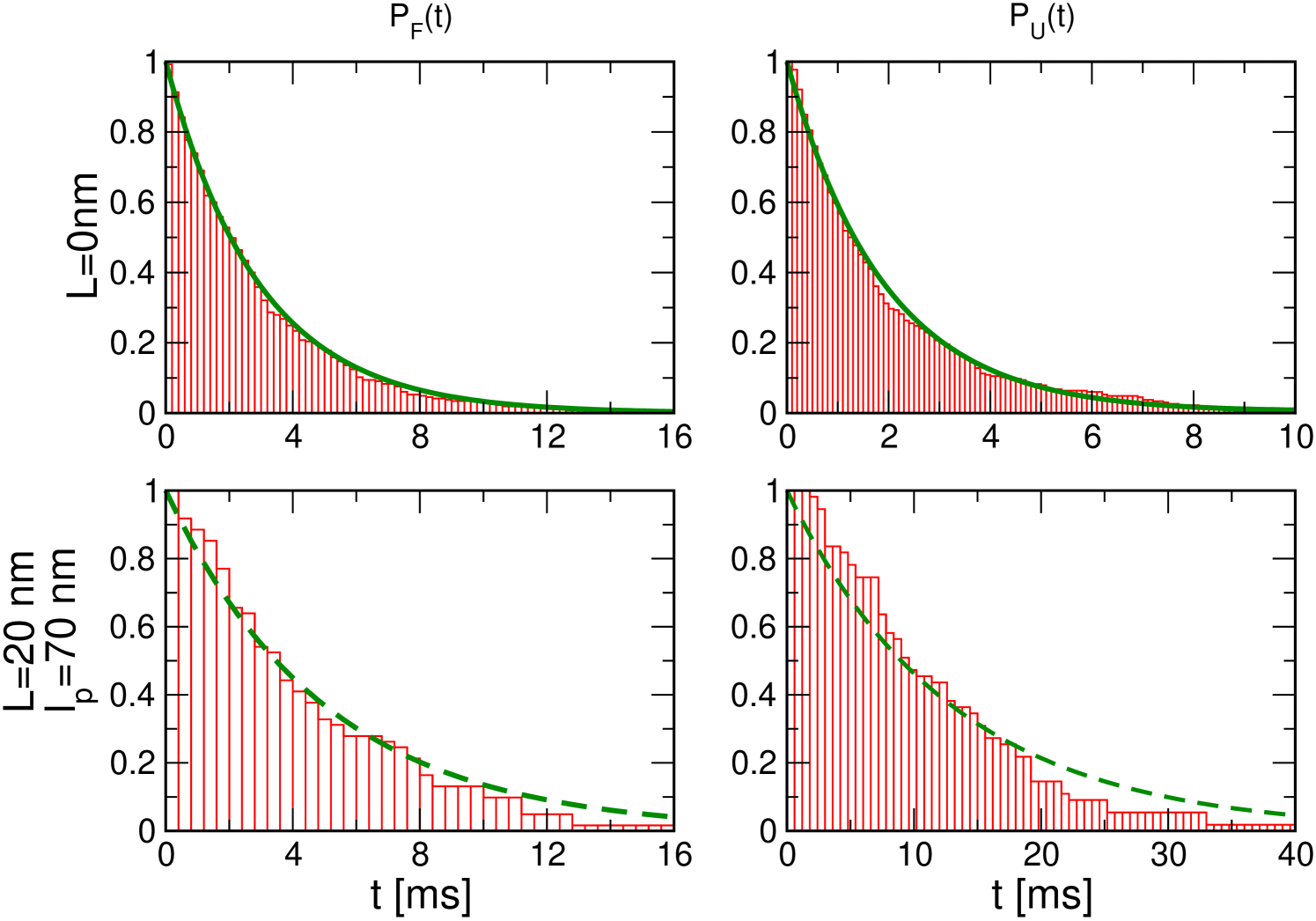

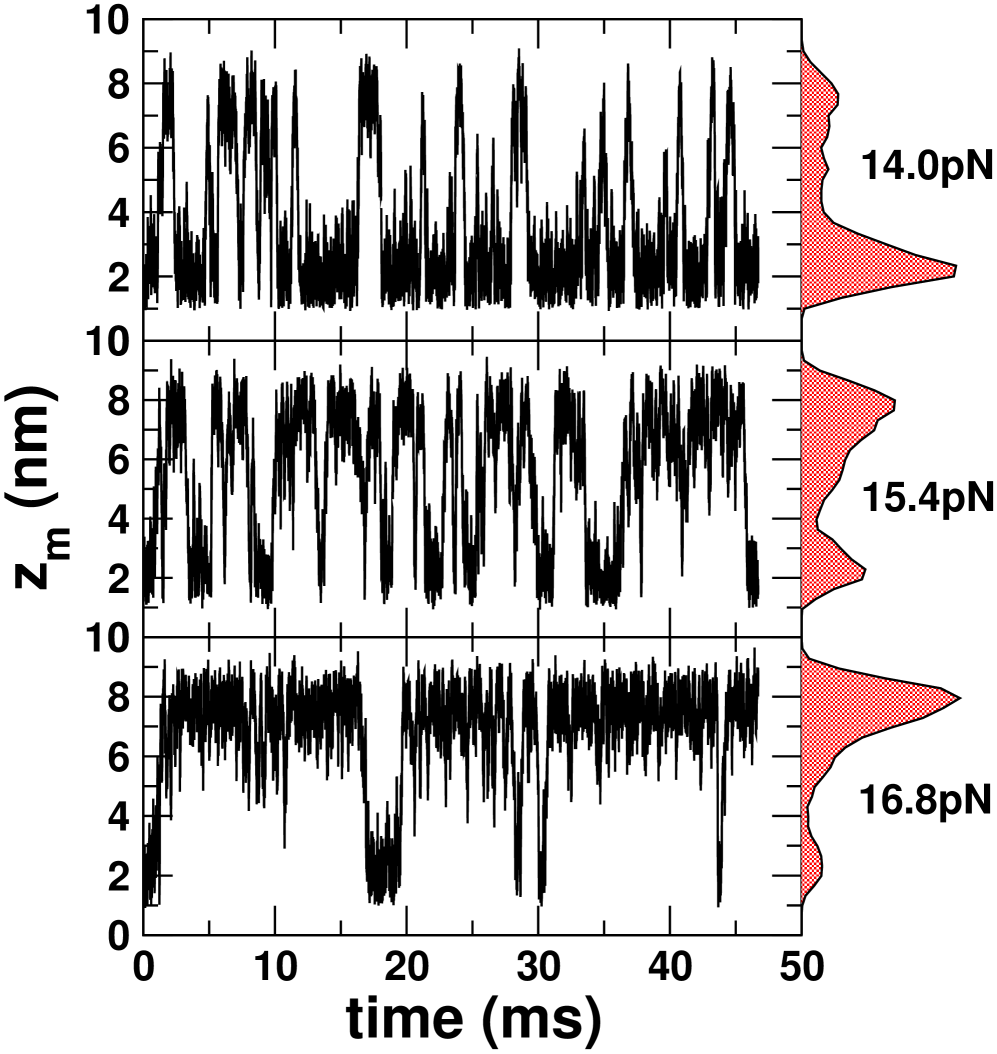

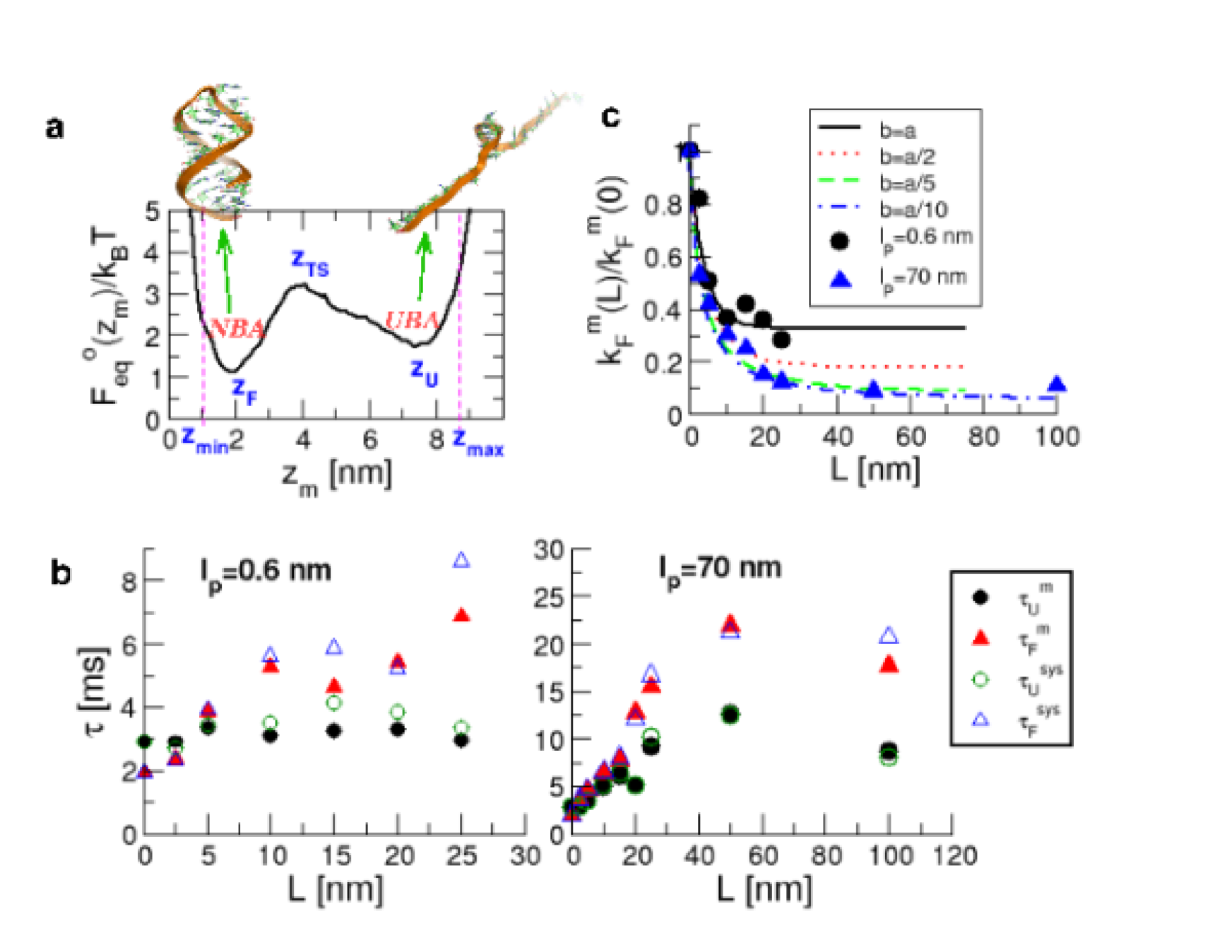

Folding and unfolding rates of P5GA and the free energy profile without handles : We first performed force clamp simulations of P5GA in the absence of handles to obtain the intrinsic (or ideal) folding () or unfolding () times, that serve as a reference for the H-RNA-H system. To obtain the boundary conditions for calculating the mean refolding and unfolding times, we collected the histograms of the time traces and determined the positions of the minima of the NBA and UBA, nm and nm (Fig. 4a). The analysis of the time traces provides the transition times in which reaches starting from . The mean unfolding time is obtained using either , or from the fits to the survival probability (SI Fig. 8). The mean folding time is similarly calculated, and the two methods give similar results. The values of and computed from the time trace of are 2.9 ms and 1.9 ms, respectively. At pN and nm, the equilibrium constant , which shows that the bare molecular free energy is slightly tilted towards NBA at pN.

Hopping times depend on the handle characteristics : The values of the folding () and unfolding() times were also calculated for the P5GA hairpin with attached handles (Fig. 1). As the length of the handles increases both and increase gradually, and the equilibrium distribution shifts towards the UBA, i.e. increases (Fig. 4b). Strikingly, the use of flexible handles results in minimal deviations of and from their intrinsic values (Fig.4b). Attachment of handles (stiff or flexible) to the 5’ and 3’ ends restricts their movement, which results in a decrease in the number of paths to the NBA and UBA. Thus, both and increase (Fig.4b). As the stiffness of the handle increases the extent of pinning increses. These arguments show that flexible and short handles, that have the least restriction on the fluctuations of the 5’ and 3’ ends of the hairpin, cause minimal perturbation to the intrinsic RNA dynamics, and hence the hopping rates.

Because the experimentally accessible quantity is the extension of the H-RNA-H, it is important to show that the transition times can be reliably obtained using . Although differs from in amplitude, the “phase” between the two quantities track each other reliably throughout the simulation, even when the handles are long and flexible (see SI Fig.7). We calculated and by analyzing the trajectories using the same procedure used to compute their intrinsic values. Comparison of () and () for both stiff and flexible handles shows excellent agreement at all values (Fig.4b). Thus, it is possible to infer the RNA dynamics by measuring .

Theoretical predictions using the GRM are consistent with the simulations: The simulation results can be fully understood using the GRM (Fig 3a), for which we can exactly solve the overdamped Langevin equation using the discrete representation of the Gaussian chain (see Methods). By assuming that transverse fluctuations are small (which is reasonable under the relatively high tension of pN), we use the Wilemski and Fixman (WF) theory FixmanJCP74II to determine an approximate time of contact formation () as a function of (i.e. increasing handle ‘stiffness’) and . The refolding rate of the RNA hairpin under tension is analogous to . A plot of versus (Fig. 4c) illustrates that smaller deviations from the handle-free values occur when is small. Moreover, Fig. 4c shows that the refolding rate decreases for increasing regardless of the stiffness of the chain. The saturating value of as depends on , with ‘stiffer’ handles having a much larger effect on the folding rate. While the handles used in LOT experiments are significantly longer than the handle lengths considered here, the saturation of the folding rate suggests that nm is sufficiently long for finite-size effects to be negligible.

We also find the dependence of on agrees well with the behavior observed in the simulation of P5GA.

The ratio for agrees well with the trends of the flexible linker ( nm) for all of the simulated lengths, with both saturating at for large .

The trends for ‘stiffer’ chains (smaller ) in the GRM qualitatively agree with the P5GA simulation with stiff handles ( nm), with remarkably good agreement for over the entire range of .

The GRM, which captures the physics of both the equilibrium and kinetic properties of the more complicated H-RNA-H, provides a theoretical basis for extracting kinetic information from experimentally (or computationally) determined folding landscapes.

Free energy landscapes and hopping rates: Stiff handles are needed to obtain Block06Science that resembles , whereas the flexible handles produce hopping rates that are close to their handle-free values. These two findings appear to demand two mutually exclusive requirements in the choice of the handles in LOT experiments. However, if is a good reaction coordinate, then it should be possible to extract the hopping rates using accurately measured at , using handles with small . The (un)folding times can be calculated using the mean first passage time (Kramers’ rate expression) with appropriate boundary conditions ZwanzigBook ,

| (1) |

where , , and are defined in Fig. 4a. The effective diffusion coefficient is obtained by equating () in equation (1), with , to the simulated . We calculated the -dependent and by evaluating equation (1) using . The calculated and simulated results for P5GA are in good agreement (Fig 5a-b). At the higher force ( pN), the statistics of hopping transition within our simulation time is not sufficient to establish ergodicity. As a result, the simulation results are not as accurate at high forces (see SI Fig. 9). To further show that the use of in equation (1) gives accurate hopping rates, we calculated for the GRM and compared the results with direct simulations of the handle-free GRM, which allows the study of a wider range of forces (see Methods). The results in Fig. 5c show that indeed gives very accurate values for the transition times from the UBA and NBA over a wide force range.

CONCLUSIONS

The self-assembly of RNA and proteins may be viewed as a diffusive process in a multi-dimensional folding landscape. To translate this physical picture into a predictive tool, it is important to discern a suitable low-dimensional representation of the complex energy landscape, from which the folding kinetics can be extracted.

Our results show that, in the context of nucleic acid hairpins, precise measurement of the sequence-dependent folding landscape of RNA is sufficient to obtain good estimates of the -dependent hopping rates in the absence of handles. It suffices to measure at using stiff handles, while at other values for can be obtained by tilting . The accurate computation of the hopping rates using show that is an excellent reaction coordinate for nucleic acid hairpins under tension. Further theoretical and experimental work is needed to test if the proposed framework can be used to predict the force dependent hopping rates for other RNA molecules that fold and unfold through populated intermediates.

METHODS

RNA hairpin: The Hamiltonian for the RNA hairpin with nucleotides, which is modeled using the self-organized polymer (SOP) model HyeonBJ07 , is

| (2) | |||||

where and is the distance between monomers and in the native structure. The first term enforces backbone chain connectivity using the finite extensible nonlinear elastic (FENE) potential, with pNnm-1 and nm. The Lennard-Jones interaction (second term in equation (2)) describes interactions only between native contacts (defined as nm for ), with if monomers and are within 1.4 nm in the native state, and otherwise. Non-native interactions are treated as purely repulsive (the third term in equation (2)) with nm. We take pNnm and pNnm for the strength of interactions. In the fourth term, the repulsion between the and interaction sites along the backbone has nm to prevent disruption of the native helical structure.

Handle polymers: The handles are modeled using the Hamiltonian

| (3) |

The neighboring interaction sites, with an equilibrium distance nm, are harmonically constrained with a spring constant pNnm-1.

In the second term of eq. (3), the strength of the bending potential, , determines the handle flexibility.

We choose two values, 7.0 pNnm and 561 pNnm to model flexible and semiflexible handles respectively, and assign pNnm to the junction connecting two ends of the RNA and the handles.

We determine the corresponding persistence length for the two values as and 70 nm (see SI text).

The contour length of each handle is varied from .

Generalized Rouse model (GRM): The Hamiltonian for the GRM (Fig. 3a) is

| (4) | |||||

where

| (7) |

The first two terms in equation (4) are the discrete connectivity potentials for the two handles, each with bonds ( monomers), and with Kuhn length . The mechanical force in the third term is applied along the direction, with pN. We also fix the 5’ end of the system with a harmonic bond of strength pNnm-1 in the fourth term of eq. (4). The fifth term mimics the RNA hairpin with bonds and spacing nm. Interactions between the two ends of the RNA hairpin are modeled as harmonic bond with strength pNnm-1 that is cut off at nm (eq. (7)). When exceeds 4nm, the bond is broken, mimicking the unfolded state.

The free energies as a function of both and are most easily determined in the continuum limit of the Hamiltonian in equation (4), with . Because of the relatively large value of the external tension (), we can neglect transverse fluctuations without significantly altering the equilibrium or kinetic properties of the GRM. The refolding time, of the RNA mimic (Fig. 3a), which is the WF closure time FixmanJCP74II , can be determined by numerically diagonalizing the Rouse-like matrix with elements Edwardsbook .

Acknowledgements : We are grateful to Arthur Laporta and N. Toan for useful discussions. This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation (CHE 05-14056).

References

- (1) A. Fersht. Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science : A Guide to Enzyme Catalysis and Protein Folding. W. H. Freeman Company, 1998.

- (2) J.A. Doudna and T.R. Cech. The chemical repertoire of natural ribozymes. Nature, 418(11):222–228, 2002.

- (3) C. M. Dobson. Protein misfolding, evolution and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci., 24:329–332, 1999.

- (4) K. A. Dill and H. S. Chan. From Levinthal to Pathways to Funnels. Nature Struct. Biol., 4:10–19, 1997.

- (5) J. N. Onuchic and P. G. Wolynes. Theory of protein folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 14:70–75, 2004.

- (6) D. Thirumalai and C. Hyeon. RNA and Protein folding: Common Themes and Variations. Biochemistry, 44(13):4957–4970, 2005.

- (7) T. E. Fisher, P. E. Marszalek, and J. M. Fernandez. Stretching single molecules into novel conformations using the atomic force microscope. Nature Struct. Biol., 7(9):719–724, 2000.

- (8) J. Liphardt, B. Onoa, S. B. Smith, I. Tinoco, Jr., and C. Bustamante. Reversible unfolding of single RNA molecules by mechanical force. Science, 292:733–737, 2001.

- (9) E. Rhoades, E. Gussakovsky, and G. Haran. Watching proteins fold one molecule at a time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 100:3197–3202, 2003.

- (10) P. T. X. Li, D. Collin, S. B. Smith, C. Bustamante, and I. Tinoco, Jr. Probing the Mechanical Folding Kinetics of TAR RNA by Hopping, Force-Jump, and Force-Ramp Methods. Biophys. J., 90:250–260, 2006.

- (11) B. Schuler, E.A. Lipman, and W.A. Eaton. Probing the free-energy sufrace for protein folding with single-molecule fluorescence spectroscopy. Nature, 419:743–747, 2002.

- (12) X. Zhuang and M. Rief. Single-molecule folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 13:86–97, 2003.

- (13) R. Merkel, P. Nassoy, A. Leung, K. Ritchie, and E. Evans. Energy landscapes of receptor-ligand bonds explored with dynamic force spectroscopy. Nature, 397:50–53, 1999.

- (14) M. T. Woodside, W. M. Behnke-Parks, K. Larizadeh, K. Travers, D. Herschlag, and S. M. Block. Nanomechanical measurements of the sequence-dependent folding landscapes of single nucleic acid hairpins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 103:6190–6195, 2006.

- (15) M. T. Woodside, P. C. Anthony, W. M. Behnke-Parks, K. Larizadeh, D. Herschlag, and S. M. Block. Direct measurement of the full, sequence-dependent folding landscape of a nucleic acid. Science, 314:1001–1004, 2006.

- (16) P. T. X. Li, C. Bustamante, and I. Tinoco Jr. Real-time control of the energy landscape by force directs the folding of RNA molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 104:7039–7044, 2007.

- (17) H. Dietz and M. Rief. Exploring the energy landscape of GFP by single-molecule mechanical experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 101(46):16192–16197, 2004.

- (18) M. Mickler, R. I. Dima, H. Dietz, C. Hyeon, D. Thirumalai, and M. Rief. Revealing the bifurcation in the unfolding pathways of GFP by using single-molecule experiments and simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 104:20268–20273, 2007.

- (19) C. Hyeon and D. Thirumalai. Can energy landscape roughness of proteins and RNA be measured by using mechanical unfolding experiments? Proc. Natl .Acad. Sci., 100:10249–10253, 2003.

- (20) R. Nevo, V. Brumfeld, R. Kapon, P. Hinterdorfer, and Z. Reich. Direct measurement of protein energy landscape roughness. EMBO reports, 6(5):482, 2005.

- (21) M. Schlierf, H. Li, and J. M. Fernandez. The unfolding kinetics of ubiquitin captured with single-molecule force-clamp techniques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 101:7299–7304, 2004.

- (22) J. Brujić, R. I. Hermans Z, K. A. Walther, and J. M. Fernandez. Single-molecule force spectroscopy reveals signatures of glassy dynamics in the energy landscape of ubiquitin. Nature Physics, 2:282–286, 2006.

- (23) B. Onoa, S. Dumont, J. Liphardt, S. B. Smith, I. Tinoco, Jr., and C. Bustamante. Identifying Kinetic Barriers to Mechanical Unfolding of the T. thermophila Ribozyme. Science, 299:1892–1895, 2003.

- (24) D. K. Klimov and D. Thirumalai. Stretching single-domain proteins: Phase diagram and kinetics of force-induced unfolding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 96(11):6166–6170, 1999.

- (25) C. Hyeon and D. Thirumalai. Mechanical unfolding of RNA hairpins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 102:6789–6794, 2005.

- (26) M. Manosas, D. Collin, and F. Ritort. Force-dependent fragility in RNA hairpins. Phys. Rev. Lett., 96:218301, 2006.

- (27) D. K. West, D. J. Brockwell, P. D. Olmsted, S. E. Radford, and E. Paci. Mechanical Resistance of Proteins Explained Using Simple Molecular Models. Biophys. J., 90:287–297, 2006.

- (28) O. K. Dudko, G. Hummer, and A. Szabo. Intrinsic rates and activation free energies from single-molecule pulling experiments. Phys. Rev. Lett., 96:108101, 2006.

- (29) C. Hyeon and D. Thirumalai. Measuring the energy landscape roughness and the transition state location of biomolecules using single molecule mechanical unfolding experiments. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter, 19:113101, 2007.

- (30) M. Manosas and F. Ritort. Thermodynamic and Kinetic Aspects of RNA pulling experiments. Biophys. J., 88:3224–3242, 2005.

- (31) C. Hyeon and D. Thirumalai. Forced-unfolding and force-quench refolding of RNA hairpins. Biophys. J., 90:3410–3427, 2006.

- (32) M. Manosas, J. D. Wen, P. T. X. Li, S. B. Smith, C. Bustamante, I. Tinoco, Jr., and F. Ritort. Force Unfolding Kinetics of RNA using Optical Tweezers. II. Modeling Experiments. Biophys. J., 92:3010–3021, 2007.

- (33) D. K. West, E. Paci, and P. D. Olmsted Internal protein dynamics shifts the distance to the mechanical transition state. Phys. Rev. E, 74:061912, 2006

- (34) K. Svoboda and S. M. Block. Biological applications of optical forces. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct., 23:247–285, 1994.

- (35) C. Hyeon and D. Thirumalai. Mechanical unfolding of RNA : from hairpins to structures with internal multiloops. Biophys. J., 92:731–743, 2007.

- (36) G. Wilemski and M. Fixman. Diffusion-controlled intrchain reactions of polymers. II Results for a pair of terminal reactive groups. J. Chem. Phys., 60(3):878–890, 1974.

- (37) R. Zwanzig. Nonequilibrium Statistical Mechanics. Oxford University press, New York, 2001.

- (38) M. Doi and S. F. Edwards. The Theory of Polymer Dynamics. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1988.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION (SI)

Fluctuations of the handle polymer under tension : Using the force clamp simulations of the RNA hairpin in the presence of handles, the dynamics of the fluctuations of the handle can be independently extracted by probing the time-dependent changes in the 5’ and 3’ ends of the RNA molecule. The distribution of the longitudinal fluctuations ( and ) and the dispersion in the transverse fluctuations ( or and or ) are shown in SI Fig. 6. Assuming that the force is decomposed into (with ), and using the partition function of the worm-like chain polymer under tension, Marko05PRE , one can express the longitudinal fluctuation as

| (8) |

where the force extension relations of a worm-like chain for and for are used for small and large forces, respectively Marko95Macro . These results are consistent with the fluctuations observed in the simulations. When , the transverse fluctuations are independent of the force, and are determined solely by the nature of the linker. For pN, the tension is in the regime that satisfies for both values of used in the simulations, and the longitudinal fluctuations decrease as the stiffness of the polymer increases for all (SI Fig.6a). The distribution of the extensions coincide for both the 3’ and 5’ ends of the handles for all and (SI Fig. 6a). This suggests that the constant force applied at the point propagates uniformly throughout the whole system.

The transverse fluctuations are given by

| (9) |

The transverse fluctuations also decrease as increases, with a different power. It is worth noting that the transverse fluctuations, which also increase as increases, are nearly independent of the handle stiffness if . The standard deviations of distributions are plotted with respect to the contour length at each bending rigidity (SI Fig. 6b).

The fit shows that nm and nm for nm and nm, respectively, which is consistent with the analysis in equation 9.

Determination of the persistence length of the handles : In order to determine the persistence length of the handles, we numerically generated the end-to-end distribution function of the free handles in the absence of tension, and fit the simulated distribution to the analytical result

HaBook ; HyeonJCP06

| (10) |

with and . The normalization constant ensures .

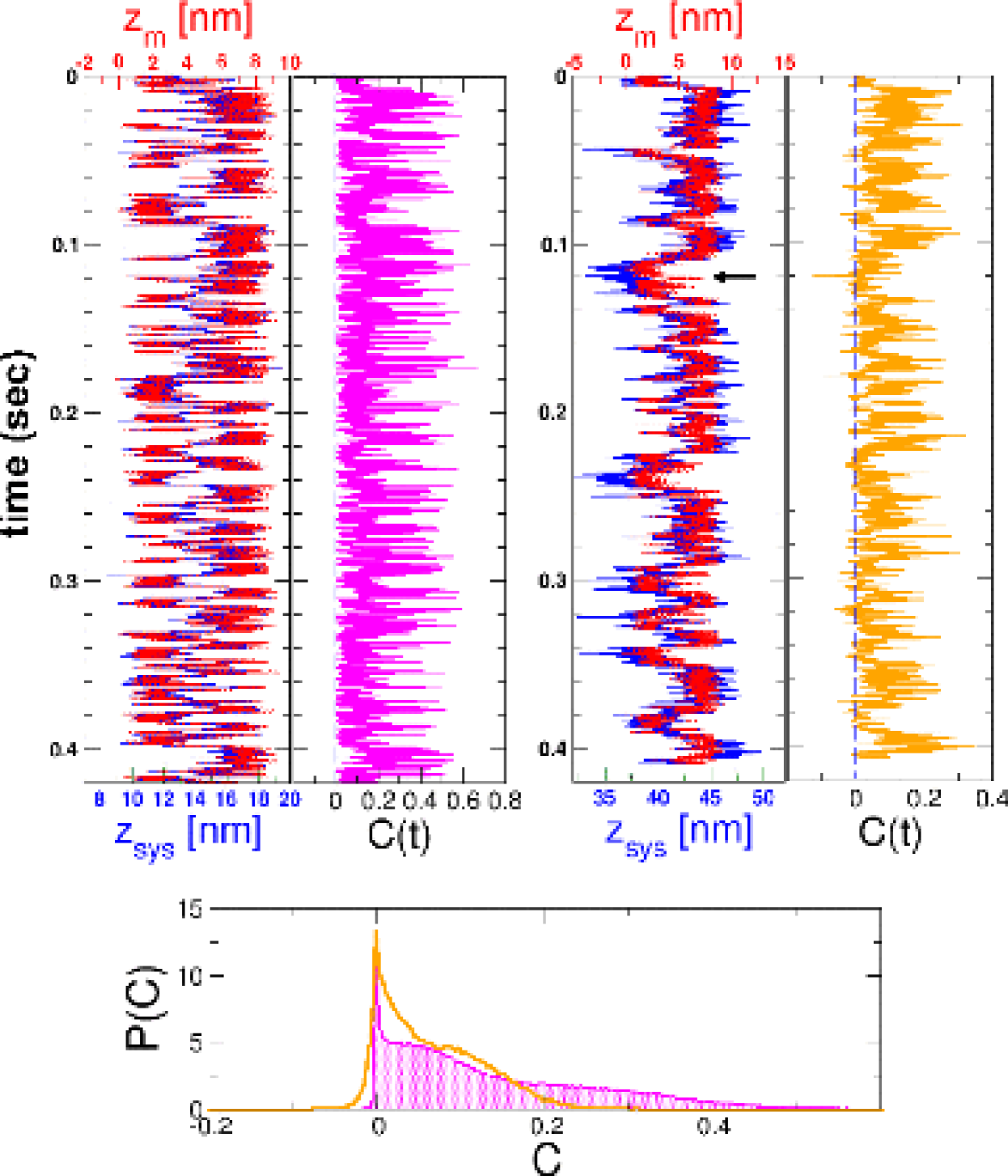

Quantifying the synchronization of and : The origin of the small discrepancy between and when the handles are flexible can be found by comparing with for the two extreme cases in Fig. 2 of the main text. To quantitatively express the synchronization between and , we defined a correlation function at each time using

| (11) |

where and are the positions of the transition states determined from and respectively. If at time , both and are in the same basins of attraction, i.e. the status of is correctly detected by the

measurement through the handles. If , then the information of is lost due to fluctuations or the slow response of the handles. The near perfect synchronization between and for nm and nm are reflected in for almost all . Thus, when the handles are stiff, , which implies that faithfully reflects the dynamics () of the hairpin. In contrast, with nm and nm, can not be determined from using .

The amplitudes of are typically larger than that of , leading to occasionally (shown by an arrow on the right plot in SI Fig. 7).

The histograms of for the two extreme cases show that the dynamics between and are more synchronous for the rigid and short handles () than for the flexible and longer handles () (see the graph at the bottom in the SI Fig.7). The finding that short and stiff () handles minimize the differences between and is related to the tension-dependent fluctuations in the linkers.

References

- (1) Yan, J., Kawamura, R. & Marko, J. F. Statistics of loop formation along double helix DNAs. Phys. Rev. E 71, 061905 (2005).

- (2) Marko, J. F. & Siggia, E. D. Stretching DNA. Macromolecules 28, 8759–8770 (1995).

- (3) Thirumalai, D. & Ha, B.-Y. Theoretical and Mathematical Models in Polymer Research, chapter I. Statistical Mechanics of Semiflexible Chains: A Mean Field Variational Approach, 1–35. Academic Press, San Diego (1998). edited by A. Grosberg.

- (4) Hyeon, C. & Thirumalai, D. Kinetics of interior loop formation in semiflexible chains. J. Chem. Phys. 124, 104905 (2006).

- (5) Woodside, M. T. et al. Direct Measurement of the Full, Sequence-Dependent Folding Landscape of a Nucleic Acid. Science 314, 1001–1004 (2006).