Ground-state phase diagram of the one-dimensional -- model at quarter filling

Abstract

We study the ground state of the one-dimensional “-- model,” which is a variant of the - model with an additional channel degree of freedom. The model is not only a generalization of the - model but also an effective model of the two-channel Kondo lattice model in the strong-coupling region. The low-energy excitations and correlation functions are systematically calculated by the density matrix renormalization group method, and the ground-state phase diagram at quarter filling consisting of a Tomonaga-Luttinger liquid, spin-gap state, channel-gap state, insulator, and phase separation is determined. We find that weak channel fluctuations stabilize the spin-gap state, while strong channel fluctuations lead to the transition to the insulator.

I INTRODUCTION

Quantum fluctuations are important features of microscopic systems, which give rise to plenty of interesting phenomena. In condensed matter physics, spin fluctuations play an important role in realizing various quantum states, such as spin liquids and superconductivity. One of the minimal theoretical models containing both spin and charge degrees of freedom is the - model. The model was originally proposed to describe high- superconductivity [1], and its one-dimensional model has been studied to understand the fundamental properties of strongly correlated systems. Although this model contains only the kinetic energy term and the exchange energy term, various quantum states including a spin-gap state are realized [2], and it is interesting to investigate whether new quantum states appear when we include additional interactions existing in more realistic systems. One simple extension is the inclusion of repulsive interaction between the neighboring electrons. It has been reported that the repulsive interaction stabilizes the spin-gap phase at quarter filling [3], but other new states have not yet been obtained. Another approach to extend the - model is to add new degrees of freedom of electrons.

Praseodymium contained in cage-shaped composites, such as , has a non-Kramers doublet as the crystal-field ground state [4, 5]. The theoretical model of such materials is the two-channel Kondo lattice model (TCKLM)[6, 7], which has multiple degrees of freedom associated with the non-Kramers doublets. As one of the simplest models of interacting electron systems consisting of multiple degrees of freedom, we propose the “-- model,” which is not only an extension of the - model but also an effective model of the TCKLM in the strong-coupling region.

In this paper, we study the ground-state properties of the model by the density matrix renormalization group (DMRG) method and investigate the effect of the channel degree of freedom on the ground state. The obtained results show that the spin-gap state is stabilized by weak channel fluctuations, while strong channel fluctuations lead to the transition to the insulator.

II MODEL

The model we study here is the following -- model:

| (1) |

where and are the creation operators of particles and “holes” at the th site with spin and channel , respectively, and the empty and double occupancies of and are inhibited:

| (2) |

where is the number operator of the particles. The spin and channel-pseudospin operators are defined as and , respectively.

This model is not only a generalization of the extended - model but also derived from the TCKLM

| (3) | ||||

| (4) |

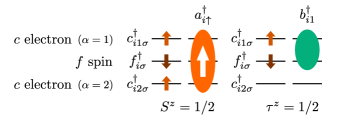

as follows: assuming that the number of conduction electrons per local spins satisfies , the effective Hamiltonian in the strong-coupling region is given by the second-order perturbation of from the limit . In this case, and are the composite particles defined as and , respectively, as schematically represented in Fig. 1. The transfer integral in Eq. (1) is given as and the effective interactions are

| (5) |

The interactions and are the two largest terms obtained by the perturbation expansion, and the other ones, including next-nearest hopping, are ignored. The neglected long-range interactions are expected to suppress the phase separation caused by the above two interactions. Instead of treating all such terms explicitly, we consider the repulsion term to suppress the phase separation. Note that when , which corresponds to the absence of the particles (), the model is reduced to the Heisenberg model of the channel degree of freedom [7].

In this study, we analyze the ground state of the Hamiltonian of Eq. (1) with an equal number of particles and holes at (quarter filling, ). This filling corresponds to in the TCKLM. Throughout this paper, we fix the nearest-neighbor interaction as and take the transfer integral as the unit of energy.

III METHOD

We use the DMRG method [8, 9] to analyze the ground states of the Hamiltonian of Eq. (1). In this method, the accuracy of the ground-state wave function is systematically controlled by the number of remaining states . We increase up to 400 to see the convergence of the results, where the truncation error is less than . The system size is in the range of 128–192.

To suppresses the finite-size effect caused by the open boundary conditions used in the DMRG calculation, we apply the sine square deformation (SSD) [10, *cite:ssd_gendiar2] to the Hamiltonian. Since the SSD reproduces the bulk response to an external field [12], we use this property to obtain the excitation gap of the infinite system.

IV RESULT

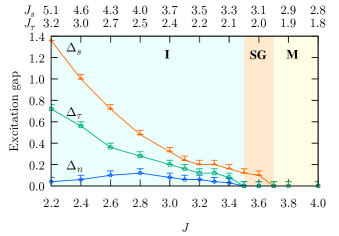

We first study the elementary excitations of the model to clarify how the interactions modify the low-energy properties of the system. We calculate the excitation gap for the charge (), spin (), and channel () degrees of freedom in the parameter space of -. Figure 2 shows the excitation gaps obtained along the line defined by Eq. (5). With decreasing the parameter of the TCKLM (with increasing and of the -- model), the spin excitation gap first opens, and then, the charge and channel gaps open.

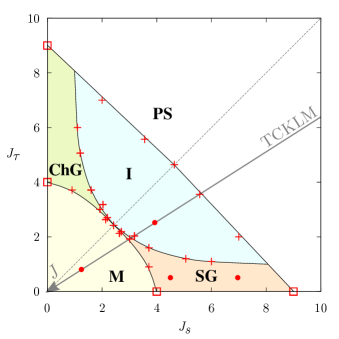

These successive transitions show the presence of the spin-gap phase. To further confirm the spin-gap phase, we systematically calculate the excitation gaps for various and and determine the ground-state phase diagram of the -- model. Figure 3 shows the obtained phase diagram consisting of five phases: metallic phase (no excitation gap), spin-gap phase (only the spin gap opens), channel-gap phase (only the channel gap opens), insulating phase (gap opens for all excitations), and phase separation. From the diagram, it is confirmed that the spin-gap phase is realized in the TCKLM between the metallic and insulating phases.

As shown in Fig. 3, the transition lines are symmetric with respect to the line of . This arises from the invariance of the Hamiltonian of Eq. (1) and the particle filling under the transformation with the exchange of and , where the symmetry of the repulsive term is ensured by the condition of Eq. (2) 111 In the system under the open boundary condition, the repulsive term modifies the local chemical potential at both ends of the system. In this study, we use the SSD and remove such a chemical-potential difference. . Since this transformation exchanges the role of spin and channel degrees of freedom, the symmetric phase diagram is obtained. In the parameter sets we have studied, the direct transition between the metallic phase and the insulating phase occurs only on the line of . This implies the existence of a quantum tetracritical point.

IV.1 Metallic phase

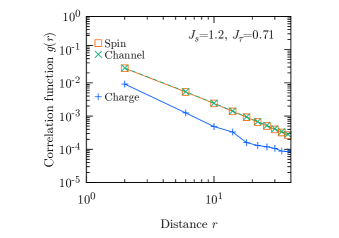

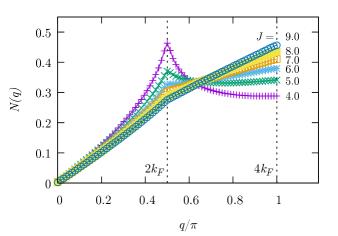

Here we focus on the metallic phase in the region of weak interaction, where all the excitations are gapless and each spin, charge, and channel degree of freedom behaves as a Tomonaga-Luttinger liquid (TLL) [14, 15]. As shown in Fig. 4, the correlation functions defined by

| (6) | ||||

| (7) |

decay in a power-law fashion . For spin and channel degrees of freedom, the exponent is at , which is almost consistent with the prediction of TLL theory , where the Luttinger parameter is determined as from the slope of the Fourier components of the charge correlation function near [2, 16, 17]. The dependence of defined by

| (8) |

also shows that the period of the charge correlation function clearly changes from (two site) to (four site) with the increase in and as presented in Fig. 5.

When exceeds a critical value, the system undergoes the transition to the spin-gap phase. At , the critical value of is close to the bandwidth . Figure 3 shows that this critical value becomes smaller with the increases in , which indicates the interaction acting on the channel degree of freedom stabilizes the spin-gap phase. We note that the critical value is insensitive to when is sufficiently smaller than .

IV.2 Spin-gap phase

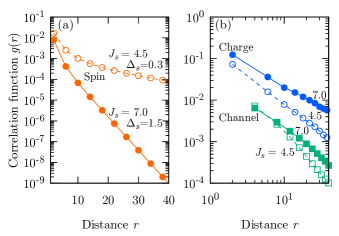

As discussed above, the increase in and enhances the spin gap, which makes the slope of the exponential decay of the spin correlation function steeper, as shown in Fig. 6(a). For the charge and channel correlation functions, the power-law behavior is confirmed, as seen in Fig. 6(b). The power-law exponent of the charge correlation function slightly decreases with the increase in the spin gap.

IV.3 Insulating phase

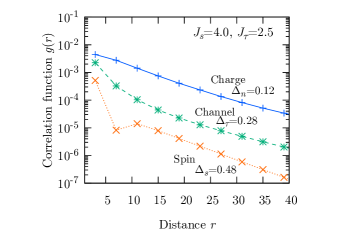

We finally investigate the insulating state. In the insulating phase, all the excitations have a finite energy gap, and the correlation functions decay exponentially, as shown in Fig. 7, where we find almost the same slope, although the charge gap is much smaller than the spin gap. We think this is a result of the alternating product state wave function of the spin and channel singlets, as shown later.

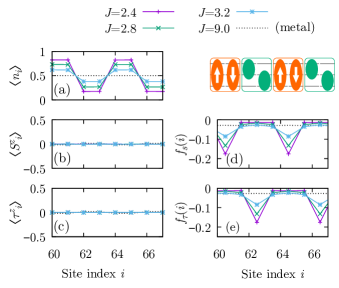

To find the symmetry-breaking order of the insulating phase, we calculate several local expectation values. Figure 8 shows the site dependence of the local densities and nearest-neighbor correlations, defined as

| (9) | ||||

| (10) |

where is the center position of the two operators. We find the charge density has 2 (four site) oscillation, whereas the spin and channel densities and remain zero everywhere. In addition, the nearest-neighbor correlations strongly correlate with the charge density oscillation. These results suggest that the insulating phase is a product state of spin and channel singlets, as schematically shown in Fig. 8. The spin-gap state is then considered as a state in which only the spin degree of freedom forms singlet pairs.

As shown in Fig. 3, the transition to the insulating state and the opening of the channel gap simultaneously occur in the region of . With the increase in from zero, the critical value of which opens the channel gap decreases from almost the bandwidth of to but never goes down to zero, which indicates the cooperation of the spin and channel degrees of freedom is essential for the emergence of the insulating phase.

Here we comment on the effect of the nearest-neighbor repulsion . This term is added to effectively include the higher-order interactions existing in the original TCKLM, which suppress the transition to the phase separation. As the nearest-neighbor repulsion leads to the metal-insulator transition in the extended Hubbard model at quarter filling [18, 19], this may affect the phase diagram. However, the insulating state caused by the nearest-neighbor repulsion is characterized by the (2 sites) charge densities, which is clearly different from the insulating state found in the present study, where only (4 sites) oscillation appears. We therefore think the repulsion term is not essential in the present analysis.

V CONCLUSION

We have studied the ground states of the -- model, which is a minimal model consisting of multiple degrees of freedom. The low-energy excitations of the spin, charge and channel degrees of freedom have been calculated by the DMRG method with the SSD, and it was shown that the phase transition occurs from the metallic state to the spin-gap or channel-gap state when the exchange interactions exceed almost the bandwidth, roughly . For the symmetric case of , however, the direct transition to the insulating state takes place. These results imply that weak channel fluctuations stabilize the spin-gap state of the - model, while strong channel fluctuations lead to the transition to the insulating state which is characterized by the alternating product state of the spin and channel singlets.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant No. JP19K03708.

References

- Zhang and Rice [1988] F. C. Zhang and T. M. Rice, Phys. Rev. B 37, 3759 (1988).

- Moreno et al. [2011] A. Moreno, A. Muramatsu, and S. R. Manmana, Phys. Rev. B 83, 205113 (2011).

- Troyer et al. [1993] M. Troyer, H. Tsunetsugu, T. M. Rice, J. Riera, and E. Dagotto, Phys. Rev. B 48, 4002 (1993).

- Cox [1987] D. L. Cox, Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 1240 (1987).

- Onimaru and Kusunose [2016] T. Onimaru and H. Kusunose, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 85, 082002 (2016).

- Nozières and Blandin [1980] P. Nozières and A. Blandin, J. Phys. (Paris) 41, 193 (1980).

- Schauerte et al. [2005] T. Schauerte, D. L. Cox, R. M. Noack, P. G. J. van Dongen, and C. D. Batista, Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 147201 (2005).

- White [1992] S. R. White, Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 2863 (1992).

- White [1993] S. R. White, Phys. Rev. B 48, 10345 (1993).

- Gendiar et al. [2009] A. Gendiar, R. Krcmar, and T. Nishino, Prog. Theor. Phys. 122, 953 (2009).

- Gendiar et al. [2010] A. Gendiar, R. Krcmar, and T. Nishino, Prog. Theor. Phys. 123, 393 (2010).

- Hotta and Shibata [2012] C. Hotta and N. Shibata, Phys. Rev. B 86, 041108(R) (2012).

- Note [1] In the system under the open boundary condition, the repulsive term modifies the local chemical potential at both ends of the system. In this study, we use the SSD and remove such a chemical-potential difference.

- Haldane [1981] F. D. M. Haldane, J. Phys. C 14, 2585 (1981).

- Voit [1995] J. Voit, Rep. Prog. Phys 58, 977 (1995).

- Clay et al. [1999] R. T. Clay, A. W. Sandvik, and D. K. Campbell, Phys. Rev. B 59, 4665 (1999).

- Schulz [1990] H. J. Schulz, Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 2831 (1990).

- Mila and Zotos [1993] F. Mila and X. Zotos, Europhys. Lett. 24, 133 (1993).

- Shirakawa and Jeckelmann [2009] T. Shirakawa and E. Jeckelmann, Phys. Rev. B 79, 195121 (2009).