Heavy element abundances in P-rich stars: A new site for the -process?

Abstract

The recently discovered phosphorus-rich stars pose a challenge to stellar evolution and nucleosynthesis theory, as none of the existing models can explain their extremely peculiar chemical abundances pattern. Apart from the large phosphorus enhancement, such stars also show enhancement in other light (O, Mg, Si, Al) and heavy (e.g., Ce) elements. We have obtained high-resolution optical spectra of two optically bright phosphorus-rich stars (including a new P-rich star), for which we have determined a larger number of elemental abundances (from C to Pb). We confirm the unusual light-element abundance pattern with very large enhancements of Mg, Si, Al, and P, and possibly some Cu enhancement, but the spectra of the new P-rich star is the only one to reveal some C(+N) enhancement. When compared to other appropriate metal-poor and neutron-capture enhanced stars, the two P-rich stars show heavy-element overabundances similar to low neutron density -process nucleosynthesis, with high first- (Sr, Y, Zr) and second-peak (Ba, La, Ce, Nd) element enhancements (even some Pb enhancement in one star) and a negative [Rb/Sr] ratio. However, this -process is distinct from the one occurring in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars. The notable distinctions encompass larger [Ba/La] and lower Eu and Pb than their AGB counterparts. Our observations should guide stellar nucleosynthesis theoreticians and observers to identify the P-rich star progenitor, which represents a new site for -process nucleosynthesis, with important implications for the chemical evolution of our Galaxy.

1 Introduction

The -process channel for the synthesis of elements beyond Fe (hereafter heavy elements) was formulated as early as the pioneering work of Burbidge et al. (1957). After the observations of -process-rich stars (and C-rich; e.g., Lambert, 1985; Vanture, 1992), it was gradually admitted that this type of nucleosynthesis occurs mainly in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars (see reviews by Busso et al., 1999; Herwig, 2005; Käppeler et al., 2011; Karakas & Lattanzio, 2014). The principal alternative way to build heavy elements in stars involves -process nucleosynthesis with very high neutron densities. In contrast to the -process, the main -process stellar site is still heavily debated, alternative candidate sites being supernovae or neutron star mergers (e.g., Argast et al., 2004). In any case, the dual nucleosynthetic origin of heavy elements between the - and -processes has found remarkable support through the observation of very metal-poor stars. Indeed, thanks to their pristine composition, the heavy element abundance patterns in these stars clearly separates them into pure -process and pure -process in a nearly perfect agreement with theory (Sneden et al., 2003; Johnson & Bolte, 2004). Nevertheless, some deviations from those standard processes have appeared: first, star-to-star variations of first-peak elements (Sr, Y, Zr) around the main -process exist (Truran et al., 2002). This has led theoreticians to invoke the contribution of weak - and weak -processes in massive stars (Wasserburg et al., 1996; Pignatari et al., 2008). Secondly, a third category of metal-poor stars has appeared with an apparently heavy element abundance pattern that is somehow intermediate between the - and -processes (Barbuy et al., 1997; Jonsell et al., 2006). These observations have led modelers to revive a third neutron-capture process with intermediate neutron densities between the - and the -process, the so-called -process (Cowan & Rose, 1977). This process may notably occur in low-metallicity AGB stars (Dardelet et al., 2014; Hampel et al., 2019; Karinkuzhi et al., 2020), but there are other candidate stellar sites (super-AGBs, Doherty et al., 2015, accreting white dwarfs, Denissenkov et al., 2017, and Population III massive stars, Clarkson et al., 2018).

Masseron et al. (2020) have very recently discovered in the near-IR (-band) SDSS-IV/APOGEE-2 survey (Majewski et al., 2016) a new kind of stars, which show extremely high phosphorus (P) abundances together with high O, Al, Mg, and Si. While those authors have discussed and largely rejected almost all possible existing models in order to explain such an enhancement of light elements, they have also noted the enhancement of several heavy elements in the only available P-rich stellar optical spectrum. Masseron et al. (2020) could not find a satisfying agreement with the theoretical models regarding their neutron-capture element yield predictions either. Here, we use a more empirical approach to understanding the heavy-element nucleosynthesis in P-rich stars. We present a chemical abundance analysis - including a higher number of heavy elements (up to Pb) for two P-rich stars - and compare it with those observed in different types of metal-poor and neutron capture-rich stars; such comparison stars are chosen to better reflect the variety of neutron-capture processes in stars.

2 Observational data and chemical analysis

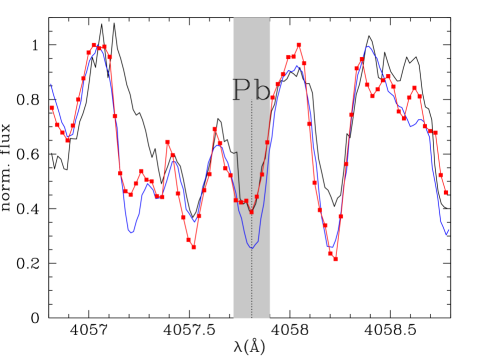

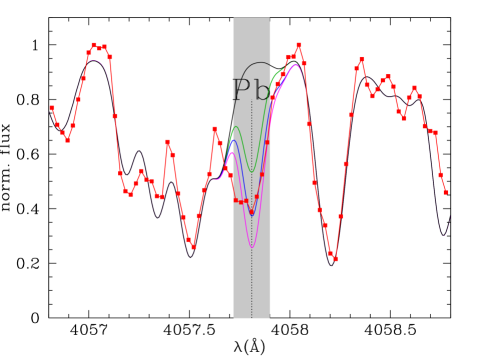

The two sample stars have been primarily identified in the near-IR (-band) by the SDSS-IV/APOGEE-2 survey (Majewski et al., 2016) with the respective IDs 2M13535604+4437076 and 2M22045404-1148287. While the first star is part of the original sample of Masseron et al. (2020), the second is a newly identified P-rich star. The observations and chemical analysis are very similar to those of Masseron et al. (2020) and will not be repeated in detail here. In brief, our analysis is based on high-resolution () optical (obtained with the NOT/FIES spectrograph) and near-IR -band () spectra (from the APOGEE instrument). The near-IR spectra allow the determination of the phosphorus abundances (also S and Co with no useful lines in the optical; see Table 1), and therefore the identification of the P-rich stars, but the optical spectra are essential for the determination of an extensive number of heavy elements (see Table 1). Unfortunately, the targets stars are K giants and are therefore relatively faint in the optical. Consequently, for each star four exposures of one hour with the optical NOT/FIES spectrograph were necessary. The NOT/FIES optical observations were obtained at three different very recent dates, on 2020 January 12 and 2020 February 20 for 2M13535604+4437076 and on 2020 August 19 for 2M22045404-1148287. After standard data reduction by the NOT/FIES pipeline and the combination of the four exposures, the signal-to-noise (S/N) achieved was 40 and 60 respectively at 5000 Å. We note, however, that we adopted a slightly different strategy regarding the data reduction of 2M22045404-1148287 for the bluest part of the spectrum (), where the S/N drops drastically, with a range of [3–10] among the several exposures. For this particular region (only used for the Pb abundance measurement), we then merged only the two best spectra rather than all four of them. This prevented contamination of the spectrum by spurious noise artifacts that would have affected our Pb determination. A separate and consistent chemical abundance analysis of the two spectra (both optical and near-IR) was then carried out with the BACCHUS code (Masseron et al., 2016). The effective temperatures, surface gravities, and microturbulence velocities were fixed to the calibrated values from the APOGEE DR16 release (Jönsson et al., 2020), while the metallicities and abundances were derived by the BACCHUS code. The final atmospheric parameters are K, , [Fe/H] , km/s, and K, , [Fe/H] , km/s for 2M13535604+4437076 and 2M22045404-1148287 respectively. The full set of derived abundances is presented in Table 1. A lower number of elements was measured in 2M13535604+4437076 because of a combination of the lower S/N of the spectra and a higher temperature. We also note that while the analysis of the near-IR and optical spectra gives very consistent results concerning the derived abundances, the metallicities are offset by 0.1 dex similarly to what has been observed in globular cluster red giants (Masseron et al., 2019), but without a clear explanation to date. In addition, we have compared the individual chemical abundance pattern of the two P-rich stars with those of another four metal-poor stars, which are representative of the three main neutron-capture nucleosynthesis processes: two CH-stars for the -process (HD 26 and HD 206983), one carbon-enhanced metal-poor star with intermediate-process (CEMP-rs or CEMP-i, HD 224959), and one extremely metal-poor star with strong -process (CS 22892-052). The stellar parameters for the first three stars are extracted from Masseron (2006), while we adopt the values from Sneden et al. (2003) for the fourth one. The choice of CH-stars as comparison stars for the -process instead a CEMP-s star (such as the star of Johnson & Bolte, 2004) was done intentionally as they have a very similar metallicity ([Fe/H] ) to our two P-rich stars. Regarding the comparison with standard stars of the -process, there are no CEMP-rs stars known at the intermediate metallicity of the actually known sample of P-rich stars (Masseron et al., 2020). Some post-AGB stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud seem to show such -process nucleosynthesis (Hampel et al., 2019), but the number of elements studied is too low to constrain the following discussion. Therefore, here we assume that the star HD 224959 is a good representative of the -process at metallicities [Fe/H] . As for the -process star representative, it also has a much lower metallicity than our P-rich stars. However, it has been demonstrated that the -process in this star is identical with the solar -process, thus a priori making the -process nucleosynthesis independent of metallicity. Finally, we stress that there are no high-resolution near-IR spectra available for the comparison stars, so we cannot provide their near-IR abundances (e.g., P) in the following plots.

3 Discussion

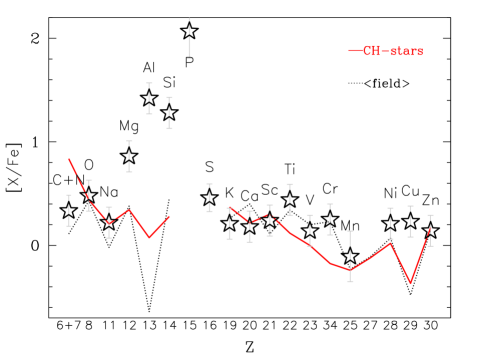

In Fig. 1, we compare the light element abundances of our two P-rich sample stars with optical spectra against the average abundances of the CH-stars and field stars at similar metallicities. First of all, the newly observed P-rich star (2M22045404-1148287) shows a chemical abundance pattern very similar to those of the other P-rich stars; i.e., it shows a clearly high phosphorus enhancement, as well as strong Mg, Si, and Al compared to field stars. Actually, whereas 2M13535604+4437076 shows the largest Mg, Al, P, and Si enhancements among the P-rich stars, 2M22045404-1148287 displays more modest enhancements; however, it is not clear whether this is due to dilution or to real variations within the nucleosynthesis of the P-rich star progenitors. In contrast, the O enhancement is weak in the two P-rich stars (and maybe even not enhanced at all given the error bars) compared to the average of the P-rich stars (Masseron et al., 2020). Curiously, we observe a significantly high Cu abundance in the two P-rich sample stars; especially in the higher S/N optical spectrum of the P-rich star 2M22045404-1148287. The nucleosynthesis of Cu could have various stellar origins (Bisterzo et al., 2005; Kobayashi et al., 2020), making very difficult the disentanglement of its true origin. Nevertheless, it is very puzzling that no simultaneous Zn enhancement is observed.

Compared to the CH-star average chemical abundance pattern, it is obvious that Mg, Si, and Al are incompatible, making it clear that the progenitors of the CH-stars are not the same as the progenitors of the newly discovered P-rich stars. We also remind the reader that none of the P-rich stars shows radial velocity variations over several years of observations (Masseron et al., 2020), which is another clear distinction from the CH-stars. However, 2M22045404-1148287 is the first P-rich star to show C(+N) enhancement; at a similar level to that of the CH-stars. As for C, it is very difficult to interpret the real reason of such an apparent enhancement, as many kinds of stars can produce C, but we may relate this to the fact that 2M22045404-1148287 is the lowest metallicity star ([Fe/H] ) among the whole P-rich star sample studied so far (15 stars, see Masseron et al., 2020). Therefore, we may tentatively invoke a metallicity effect in the P-rich star progenitor nucleosynthesis, which would only allow a significant C enhancement at the lowest metallicities.

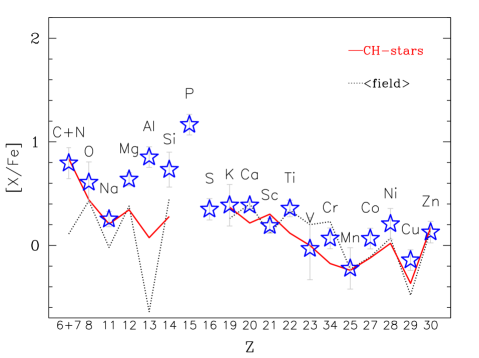

Regarding the heavy element nucleosynthesis, we have displayed all the stars (P-rich and comparison stars) in the [Ba/Fe] versus [Eu/Fe] diagram (Fig. 2), as this plane has been demonstrated to be an excellent diagnostic for separating the three main neutron-capture processes in metal-poor stars (Masseron et al., 2010). In this figure, the P-rich stars appear clearly among the CEMP-s stars, quite close to the CH-stars and the theoretical -process predictions.

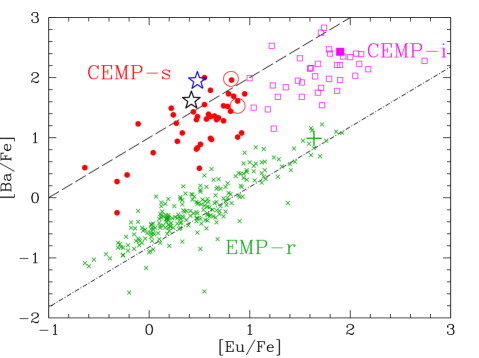

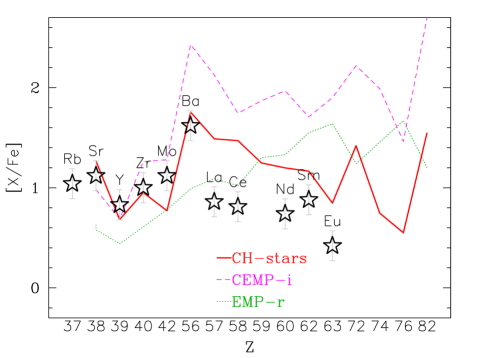

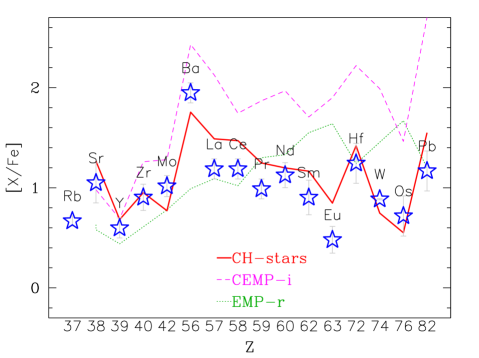

The -process signature is confirmed when examining the full distribution of heavy elements (Fig. 3). In this figure, we compare the heavy element abundance pattern of the P-rich stars against those of the CH-stars, the CEMP-i (or CEMP-rs) star and the -process-rich EMP-r star. It is clear that the P-rich star heavy element pattern is clearly incompatible with the - and -processes, particularly when comparing the Eu and Sm abundances. Conversely, the heavy element chemical pattern of the P-rich stars follows that of the CH-stars and is remarkably close in the case of 2M22045404-1148287. This strongly suggests that the P-rich star progenitors have undergone some kind of -process nucleosynthesis. We note that for an unbiased comparison of the s-process it is particularly important that the P-rich stars and the CH-stars have similar metallicities. Indeed, metallicity is known to play a key-role in -process nucleosynthesis as it affects the second-to-first peak element ratio (Gallino et al., 1998; Goriely & Mowlavi, 2000). The second-to-first peak element ratio matches remarkably well the CH-stars and the P-rich star 2M22045404-1148287 but it is less obvious with the slightly higher metallicity P-rich star 2M13535604+4437076. This discrepancy between the two P-rich stars could be related to a difference in the -process strength (Gallino et al., 1998; Goriely & Mowlavi, 2000).

There are some more element-specific differences between the CH-stars and the P-rich stars that can further constrain the details of the -process nucleosynthesis that has occurred in the P-rich star progenitors. As already noticed by Masseron et al. (2020), the Ba overabundance is particularly large compared to the other second-peak elements (e.g., La) and the corresponding CH-star values. Our differential approach with the CH-stars, displaying similar stellar parameters, confirms that the large Ba enhancement (and hence the high [Ba/La] ratio) is real and not due to NLTE or 3D effects. Such a large discrepancy between the two contiguous elements Ba and La is unusual and may provide key clues regarding the details (e.g., neutron density and exposure) of the nucleosynthesis process; something that future detailed nuclear network simulations could clarify. Nevertheless, the [Rb/Sr] ratio being negative in both cases also puts quite a low upper limit to the neutron density (i.e., cm-3). Moreover, although both P-rich stars have negative [Rb/Sr], the value for the star 2M22045404-1148287 is significantly smaller than that for 2M13535604+4437076. Taking into account that the [Rb/Sr] (or [Rb/Zr]) ratio is sensitive to the neutron density (see e.g., García-Hernández et al., 2006, and references therein), this implies that the neutron density is larger in 2M13535604+4437076.

When looking at the third-peak elements, one P-rich sample star (2M22045404-1148287, the only star where we could detect the Pb lines in the bluest optical region; see Fig. 4) shows some Pb enhancement (consistently, in principle, with the predictions for the -process in AGB stars; Van Eck et al., 2003). Interestingly, the Pb abundance in the P-rich star is lower than in the CH-stars. This relatively modest Pb enrichment may be another indication that the P-rich star progenitors have undergone an -process nucleosynthesis with distinct characteristics.

The -process is believed to occur only in AGB stars and there are no other stellar evolution and nucleosynthesis models in the literature where the -process occurs. Fortunately, variations in the details of the -process are still allowed by theory. In their nuclear network simulations at similar metallicities to those of our P-rich stars, Hampel et al. (2019) explore the [Pb/Ba] and [Ba/Sr] ratios with varying neutron density and exposure. By assuming that the temperatures and gas densities in the region where neutron-capture elements are formed in the P-rich star progenitors are similar for AGB stars, we deduce - from their work (see e.g. their Fig. 1) and our Rb, Sr, Ba, and Pb abundances - that for a neutron density below 1011, the neutron exposure in the P-rich stars is between 0.7 and 1.2 mbarn-1.

Moreover, while the -process is also capable of making Cu, it is expected to make Zn as well. But neither of the two P-rich stars shows any Zn enhancement, implying that Cu has not been enhanced by such a neutron-capture process.

Finally, we remind the reader that 31P can also be produced by the -process, thanks to the large neutron cross section of 30Si. In AGB and super-AGB star models at [Fe/H] (Karakas, 2010; Doherty et al., 2015), phosphorus production is negligible. Although the light-element chemical pattern in P-rich stars has already ruled out an AGB scenario (Masseron et al., 2020), it could be still possible that P may have a neutron-capture origin in the P-rich star progenitors, especially given that Si is strongly enhanced as well. Therefore, more extensive nuclear network simulations of neutron-capture processes with various neutron exposures and densities are strongly encouraged in order to explore the tight observational constraints reported here, with special attention to the [Rb/Sr], [Ba/La], [La/Eu], and [Pb/La] ratios, along with P production and possibly the [Cu/Zn] ratio.

4 Concluding remarks

Our detailed study of the heavy element abundance pattern of two optically bright P-rich stars lead us to conclude that it is very likely that the P-rich stars progenitors have undergone a kind of -process nucleosynthesis with potentially a low neutron density and low neutron exposure. However, their light element abundances do not correspond to AGB stars; the only stellar site currently known where such neutron-capture nucleosynthesis takes place. Therefore, whenever a new stellar site or channel for the -process is identified, it will provide clues on the nature of the P-rich star progenitors and their role in the context of Galactic chemical evolution. Thus, our observations should guide the stellar nucleosynthesis modelers. On the observational side, our slightly enhanced Pb and (probably) Cu abundances in P-rich stars, should be completely confirmed with more high-resolution optical spectroscopic P-rich star observations and/or much better S/N spectra.

References

- Argast et al. (2004) Argast, D., Samland, M., Thielemann, F. K., & Qian, Y. Z. 2004, A&A, 416, 997

- Asplund et al. (2009) Asplund, M., Grevesse, N., Sauval, A. J., & Scott, P. 2009, ARA&A, 47, 481

- Barbuy et al. (1997) Barbuy, B., Cayrel, R., Spite, M., et al. 1997, A&A, 317, L63

- Bisterzo et al. (2005) Bisterzo, S., Pompeia, L., Gallino, R., et al. 2005, Nucl. Phys. A, 758, 284

- Burbidge et al. (1957) Burbidge, E. M., Burbidge, G. R., Fowler, W. A., & Hoyle, F. 1957, Reviews of Modern Physics, 29, 547

- Busso et al. (1999) Busso, M., Gallino, R., & Wasserburg, G. J. 1999, ARA&A, 37, 239

- Clarkson et al. (2018) Clarkson, O., Herwig, F., & Pignatari, M. 2018, MNRAS, 474, L37

- Cowan & Rose (1977) Cowan, J. J., & Rose, W. K. 1977, ApJ, 212, 149

- Dardelet et al. (2014) Dardelet, L., Ritter, C., Prado, P., et al. 2014, in XIII Nuclei in the Cosmos (NIC XIII), 145

- Denissenkov et al. (2017) Denissenkov, P. A., Herwig, F., Battino, U., et al. 2017, ApJ, 834, L10

- Doherty et al. (2015) Doherty, C. L., Gil-Pons, P., Siess, L., Lattanzio, J. C., & Lau, H. H. B. 2015, MNRAS, 446, 2599

- Gallino et al. (1998) Gallino, R., Arlandini, C., Busso, M., et al. 1998, ApJ, 497, 388

- García-Hernández et al. (2006) García-Hernández, D. A., García-Lario, P., Plez, B., et al. 2006, Science, 314, 1751

- Goriely & Mowlavi (2000) Goriely, S., & Mowlavi, N. 2000, A&A, 362, 599

- Hampel et al. (2019) Hampel, M., Karakas, A. I., Stancliffe, R. J., Meyer, B. S., & Lugaro, M. 2019, ApJ, 887, 11

- Herwig (2005) Herwig, F. 2005, ARA&A, 43, 435

- Johnson & Bolte (2004) Johnson, J. A., & Bolte, M. 2004, ApJ, 605, 462

- Jonsell et al. (2006) Jonsell, K., Barklem, P. S., Gustafsson, B., et al. 2006, A&A, 451, 651

- Jönsson et al. (2020) Jönsson, H., Holtzman, J. A., Allende Prieto, C., et al. 2020, AJ, 160, 120

- Käppeler et al. (2011) Käppeler, F., Gallino, R., Bisterzo, S., & Aoki, W. 2011, Reviews of Modern Physics, 83, 157

- Karakas (2010) Karakas, A. I. 2010, MNRAS, 403, 1413

- Karakas & Lattanzio (2014) Karakas, A. I., & Lattanzio, J. C. 2014, PASA, 31, e030

- Karinkuzhi et al. (2020) Karinkuzhi, D., Van Eck, S., Goriely, S., Siess, L., & Jorissen, A. 2020, A&A, submitted

- Kobayashi et al. (2020) Kobayashi, C., Karakas, A. I., & Lugaro, M. 2020, ApJ, 900, 179

- Lambert (1985) Lambert, D. L. 1985, The chemical composition of cool stars: I - The barium stars. (Review paper), ed. M. Jaschek & P. C. Keenan, Vol. 114, 191

- Majewski et al. (2016) Majewski, S. R., APOGEE Team, & APOGEE-2 Team. 2016, Astronomische Nachrichten, 337, 863

- Masseron (2006) Masseron, T. 2006, PhD thesis, Observatoire de Paris, France

- Masseron et al. (2020) Masseron, T., García-Hernández, D. A., Santoveña, R., et al. 2020, Nature Communications, 11, 3759

- Masseron et al. (2010) Masseron, T., Johnson, J. A., Plez, B., et al. 2010, A&A, 509, A93

- Masseron et al. (2016) Masseron, T., Merle, T., & Hawkins, K. 2016, BACCHUS: Brussels Automatic Code for Characterizing High accUracy Spectra, Astrophysics Source Code Library, , , ascl:1605.004

- Masseron et al. (2019) Masseron, T., García-Hernández, D. A., Mészáros, S., et al. 2019, A&A, 622, A191

- Pignatari et al. (2008) Pignatari, M., Gallino, R., Meynet, G., et al. 2008, ApJ, 687, L95

- Roederer et al. (2014) Roederer, I. U., Preston, G. W., Thompson, I. B., et al. 2014, AJ, 147, 136

- Sneden et al. (2003) Sneden, C., Cowan, J. J., Lawler, J. E., et al. 2003, ApJ, 591, 936

- Suda et al. (2008) Suda, T., Katsuta, Y., Yamada, S., et al. 2008, PASJ, 60, 1159

- Truran et al. (2002) Truran, J. W., Cowan, J. J., Pilachowski, C. A., & Sneden, C. 2002, PASP, 114, 1293

- Van Eck et al. (2003) Van Eck, S., Goriely, S., Jorissen, A., & Plez, B. 2003, A&A, 404, 291

- Vanture (1992) Vanture, A. D. 1992, AJ, 104, 1997

- Wasserburg et al. (1996) Wasserburg, G. J., Busso, M., & Gallino, R. 1996, ApJ, 466, L109

| 2M13535604+4437076 | 2M22045404-1148287 | inst. | |||

| [X/Fe] | [X/Fe] | ||||

| C | 0.83 | 0.16 | 0.35 | 0.16 | FIES |

| N | 0.57 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.04 | FIES |

| C+N | 0.79 | 0.15 | 0.33 | 0.15 | FIES |

| O | 0.61 | 0.20 | 0.48 | 0.20 | FIES |

| Na | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.07 | FIES |

| Mg | 0.64 | 0.06 | 0.86 | 0.06 | FIES |

| Al | 0.85 | 0.10 | 1.42 | 0.10 | FIES |

| Si | 0.73 | 0.17 | 1.28 | 0.17 | FIES |

| P | 1.17 | 0.10 | 2.07 | 0.26 | APOGEE |

| S | 0.35 | 0.10 | 0.46 | 0.13 | APOGEE |

| K | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | FIES |

| Ca | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.03 | FIES |

| Sc | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.24 | 0.07 | FIES |

| Ti | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.44 | 0.08 | FIES |

| V | -0.03 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.30 | FIES |

| Cr | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.10 | FIES |

| Mn | -0.22 | 0.20 | -0.11 | 0.24 | FIES |

| Co | 0.07 | 0.10 | APOGEE | ||

| Ni | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.15 | FIES |

| Cu | -0.14 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.10 | FIES |

| Zn | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.10 | FIES |

| Rb | 0.67 | 0.05 | 1.04 | 0.05 | FIES |

| Sr | 1.05 | 0.20 | 1.12 | 0.20 | FIES |

| Y | 0.60 | 0.10 | 0.83 | 0.10 | FIES |

| Zr | 0.90 | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0.13 | FIES |

| Mo | 1.02 | 0.11 | 1.12 | 0.11 | FIES |

| Ba | 1.95 | 0.10 | 1.62 | 0.10 | FIES |

| La | 1.19 | 0.10 | 0.86 | 0.10 | FIES |

| Ce | 1.19 | 0.10 | 0.81 | 0.10 | FIES |

| Pr | 0.99 | 0.10 | FIES | ||

| Nd | 1.13 | 0.13 | 0.74 | 0.13 | FIES |

| Sm | 0.90 | 0.17 | 0.88 | 0.17 | FIES |

| Eu | 0.48 | 0.13 | 0.42 | 0.13 | FIES |

| Hf | 1.24 | 0.20 | FIES | ||

| W | 0.89 | 0.01 | FIES | ||

| Os | 0.72 | 0.20 | FIES | ||

| Pb | 1.17 | 0.20 | FIES | ||