Present address: ]Department of Physics, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

Hidden Quantum Hall Stripes in AlxGa1-xAs/Al0.24Ga0.76As Quantum Wells

Abstract

We report on transport signatures of hidden quantum Hall stripe (hQHS) phases in high () half-filled Landau levels of AlxGa1-xAs/Al0.24Ga0.76As quantum wells with varying Al mole fraction . Residing between the conventional stripe phases (lower ) and the isotropic liquid phases (higher ), where resistivity decreases as , these hQHS phases exhibit isotropic and -independent resistivity. Using the experimental phase diagram we establish that the stripe phases are more robust than theoretically predicted, calling for improved theoretical treatment. We also show that, unlike conventional stripe phases, the hQHS phases do not occur in ultrahigh mobility GaAs quantum wells, but are likely to be found in other systems.

Discovery of the integer quantum Hall effect in Si (von Klitzing et al., 1980) has paved the way to observations of many exotic phenomena in two-dimensional (2D) electron and hole systems. Two prime examples are the fractional quantum Hall effect (Tsui et al., 1982) and quantum Hall stripes (QHSs) Koulakov et al. (1996); Fogler et al. (1996); Moessner and Chalker (1996); Lilly et al. (1999a); Du et al. (1999). While fractional quantum Hall effects have been realized in many systems, including GaAs (Tsui et al., 1982), Si (Nelson et al., 1992; Kott et al., 2014), AlAs (De Poortere et al., 2002), GaN (Manfra et al., 2002), graphene (Du et al., 2009; Bolotin et al., 2009), CdTe (Piot et al., 2010), ZnO (Tsukazaki et al., 2010), Ge (Shi et al., 2015), and InAs (Ma et al., 2017), exploration of the QHS physics remains limited to GaAs (not, a).

Forming due to a peculiar boxlike screened Coulomb potential, QHSs can be viewed as charge density waves consisting of stripes with alternating integer filling factors , e.g., and (not, b). In experiments, QHSs are manifested by giant resistivity anisotropies () in half-filled Landau levels. Appearance of these anisotropies in macroscopic samples is attributed to a mysterious symmetry-breaking field Fil (2000); Koduvayur et al. (2011); Sodemann and MacDonald (2013); Pollanen et al. (2015), which nearly always aligns QHSs along the crystal axis of GaAs (not, c). While a sufficiently low disorder is necessary for the QHS formation, the absence of QHSs in systems beyond GaAs might simply be due to the lack of symmetry-breaking fields (not, d). Indeed, electron bubble phases Koulakov et al. (1996); Fogler et al. (1996); Moessner and Chalker (1996); Cooper et al. (1999); Eisenstein et al. (2002); Lewis et al. (2002); Deng et al. (2012); Rossokhaty et al. (2016); Friess et al. (2017); Bennaceur et al. (2018); Friess et al. (2018); Fu et al. (2019); Ro et al. (2019), which are close relatives of QHSs, have already been identified in graphene (Chen et al., 2019).

In this Letter, we report observation of transport signatures of the recently predicted (Huang et al., 2020) hidden QHS (hQHS) phases in a series of AlxGa1-xAs/Al0.24Ga0.76As quantum wells with . In contrast to the ordinary QHS phases, the hQHS phases are characterized by isotropic resistivity () that is independent of , unlike the isotropic liquid phases in which . These unique properties make these phases detectable without symmetry-breaking fields, thereby opening an avenue to study stripe physics in systems beyond GaAs. The wide variation of mobilities in our samples allows us to construct an experimental phase diagram in the conductivity-filling factor plane. Its comparison to theoretical predictions (Huang et al., 2020) yields the electron quantum lifetimes and the stripe density of states. The latter turns out to be lower than predicted by original the Hartree-Fock theory (Koulakov et al., 1996; Fogler et al., 1996), calling for further theoretical input. We confirm this finding by a complementary experiment on an ultrahigh mobility GaAs quantum well, where we also show that, in this sample, the hQHS phase yields to the QHS phase in agreement with the theory.

Before presenting our experimental data, we briefly summarize the physics behind the hQHS phases (Huang et al., 2020). The resistance anisotropies in the ordinary QHS phase emerge due to different diffusion mechanisms along and perpendicular to the stripes (MacDonald and Fisher, 2000; von Oppen et al., 2000; Sammon et al., 2019). In this picture, an electron drifts a distance along the -oriented stripe edge in an -directed internal electric field until it is scattered by impurities to one of the adjacent stripe edges located at a distance (Koulakov et al., 1996; Fogler et al., 1996), where is the stripe period and is the cyclotron radius. When , the diffusion coefficient in the direction is much larger that in the direction, which leads to anisotropic conductivity, , and resistivity, . Since and (Sammon et al., 2019), the anisotropy decreases with and eventually vanishes at some . At larger , the drift contribution to the diffusion along stripes can be neglected, and , like , is determined entirely by the impurity scattering. For isotropic scattering, it is easy to show (not, e) that which coincides with . As a result, the QHS phase yields to the hQHS phase in which the resistivity is isotropic and independent (since the stripe density of states does not vary with ). The hQHS phase persists until the stripe structure is destroyed by disorder at and the ground state becomes an isotropic liquid with , as predicted by Ando and Uemura (Ando and Uemura, 1974) and experimentally confirmed by Coleridge, Zawadski, and Sachrajda (CZS) (Coleridge et al., 1994).

For the hQHS phase to exist and be detected, it should span a sizable range of the filling factors . The range depends sensitively on both transport and quantum scattering rates, which control and , respectively (Huang et al., 2020). As we will see, ultrahigh mobility GaAs quantum wells do not support the hQHS phase as in these samples. On the other hand, adding the correct small amount of Al (not, f) to the GaAs well greatly expands , as it affects to a much greater extent than it does . This happens because Al acts as a short-range disorder, which contributes equally to transport and quantum scattering rates, and because at .

| Sample ID | ( cm-2) | ( cm2/Vs) | () | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.00057 | 3.0 | 6.5 | 8.0 |

| B | 0.00082 | 2.9 | 4.1 | 4.9 |

| C | 0.0078 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

Apart from different , all our AlxGa1-xAs quantum wells share an identical heterostructure design Gardner et al. (2013). Electrons are supplied by Si doping in narrow GaAs wells surrounded by narrow AlAs layers and placed at a setback distance of nm from each side of the 30-nm-wide AlxGa1-xAs well hosting the 2D electrons. Parameters of samples A, B, and C such as Al mole fraction , electron density , mobility , and Drude conductivity in units of at zero magnetic field () are listed in Table 1. The samples are approximately 4 mm squares with eight indium contacts positioned at the corners and at the midsides. Longitudinal resistances and were measured in sweeping magnetic fields using a four-terminal, low-frequency (a few Hz) lock-in technique at a temperature mK at which the resistances are nearly temperature independent. The current was sent along either the or direction using the midside contacts, and the voltage was measured between contacts along the edge. To account for anisotropies due to nonideal geometry, or was multiplied by a factor (typically ) that was chosen to make in the low field regime.

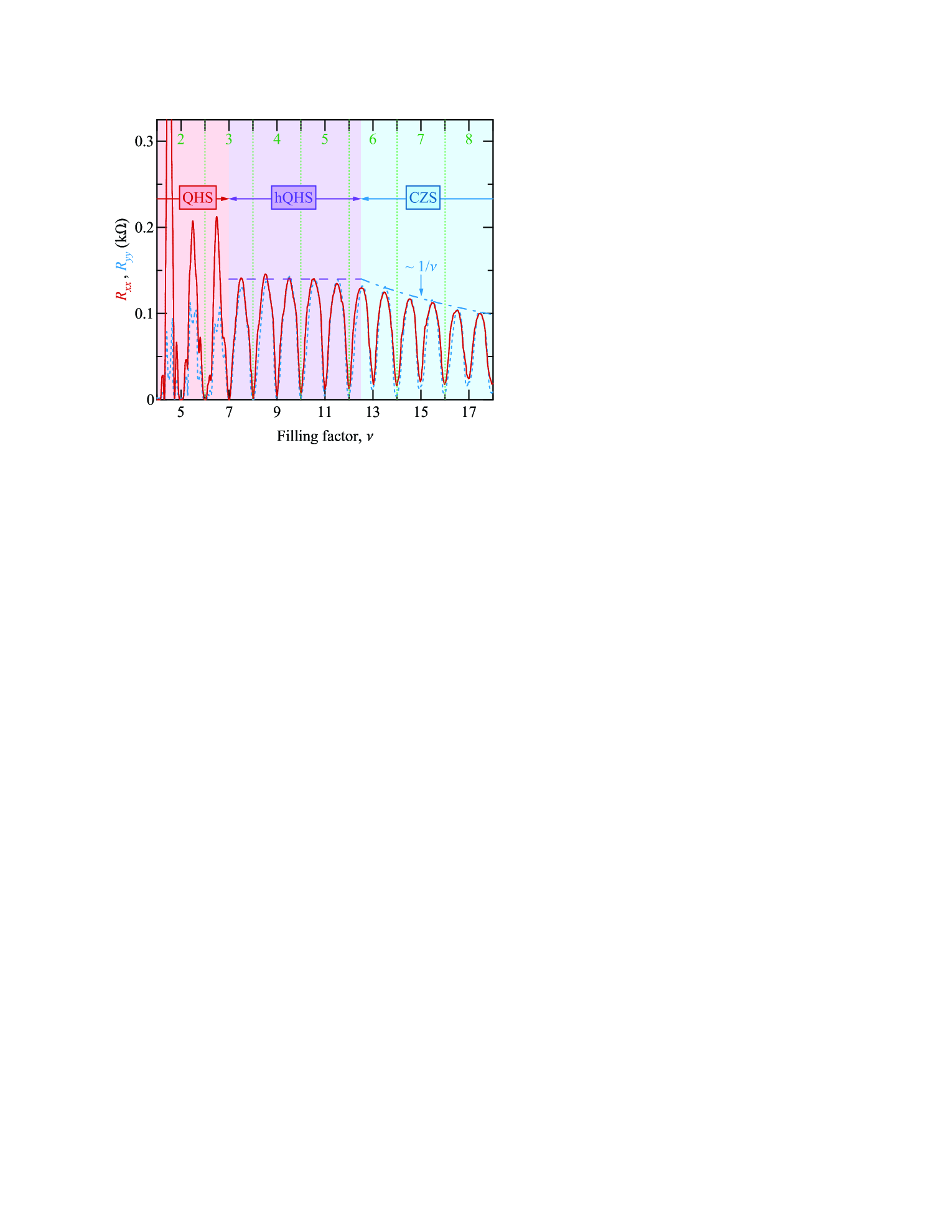

In Fig. 1, we present longitudinal resistances and as a function of filling factor measured in sample B. At low half-integer filling factors (, , and ) the data reveal conventional QHS phases, as evidenced by . At high half-integer filling factors () we identify the CZS phase in which (cf. dash-dotted line). At intermediate half-integer filling factors, , one readily confirms both characteristic features of the hQHS phase; indeed, the data show that two longitudinal resistances are practically the same () and are independent of (cf. dashed line). From Fig. 1, we can easily identify the characteristic filling factors and which mark the crossovers from the QHS to the hQHS phase and from the hQHS to the CZS phase, respectively.

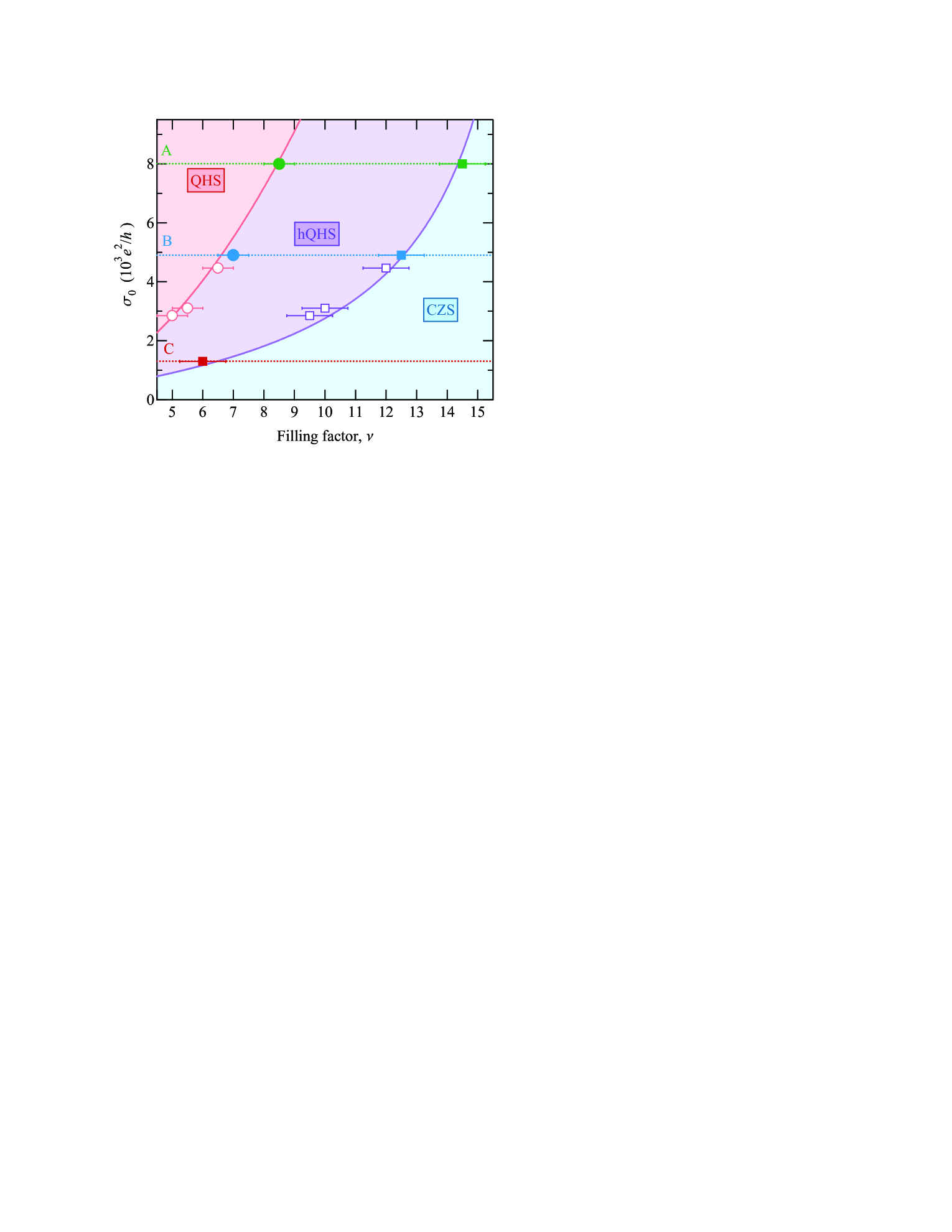

In a similar manner, we have obtained and for sample A and for sample C (which does not support the QHS phase due to higher Al mole fraction ), which we then use to construct the experimental phase diagram shown in Fig. 2. We start by adding points representing the dimensionless Drude conductivity for samples A, B, C (see Table 1) and the corresponding filling factors (solid circles) and (solid squares). To connect these data points we use the theoretical boundaries of the hQHS phase (Huang et al., 2020). The lower boundary , separating the QHS and the hQHS phases, is given by (Huang et al., 2020)

| (1) |

where (not, g) is the QHS density of states in units of the density of states per spin at , . This boundary can be obtained by either matching the parameter-free geometric average of the resistivities in the QHS phase (MacDonald and Fisher, 2000; Sammon et al., 2019) and the resistivity in the hQHS phase (Huang et al., 2020),

| (2) |

or, equivalently, by setting the resistivity anisotropy ratio to unity, (Sammon et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2020).

The higher boundary marks the crossover from the hQHS to the CZS phase and is represented by

| (3) |

This boundary can be obtained by equating and the density of states at the center of the Landau level in CZS phase, in units of the density of states at , (Raikh and Shahbazyan, 1993; Mirlin et al., 1996) or by matching and the resistivity in the CZS phase (Coleridge et al., 1994),

| (4) |

We thus see that for a given carrier density, as mentioned above, and are controlled by and , respectively. Strictly speaking, Eqs. (1), (3) are not sharp boundaries but rather gradual crossovers between corresponding phases.

With the help of Eq. (1) and experimental values of in samples A and B, we estimate , which is smaller than the theoretical estimate of (Sammon et al., 2019; not, g). We then parameterize scattering rates and as

| (5) |

where is the Al mole fraction, ns-1 per % Al (Gardner et al., 2013), and ns-1 (Gardner et al., 2013) is the transport scattering rate in the limit of . To find the remaining parameter , which is the quantum scattering rate in the limit of , we use experimental values and notice that Eqs. (1), (3) yield . Using Eq. (5) we then obtain an estimate for ns which is in good agreement with values found from low experiments (Shi et al., 2016a, 2017a; Zudov et al., 2017) on microwave-induced (Zudov et al., 2001; Ye et al., 2001; Dmitriev et al., 2012) and Hall-field-induced (Yang et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2007; Vavilov et al., 2007) resistance oscillations in GaAs quantum wells.

We next use cm-2 and (Coleridge et al., 1996; Tan et al., 2005; Hatke et al., 2013; Shchepetilnikov et al., 2017; Fu et al., 2017) to compute the phase boundaries, Eqs. (1), (3), which are shown in Fig. 2 by solid lines. Both lines pass in close proximity to the experimentally obtained (solid circles) and (solid squares) from all samples, showing excellent agreement between theory (Huang et al., 2020) and experiment. Finally, we add data points (open circles and squares) from three other AlxGa1-xAs/Al0.24Ga0.76As quantum wells that were investigated in a different context (Shi, 2017). These points are also in agreement with the theory and the present experiment.

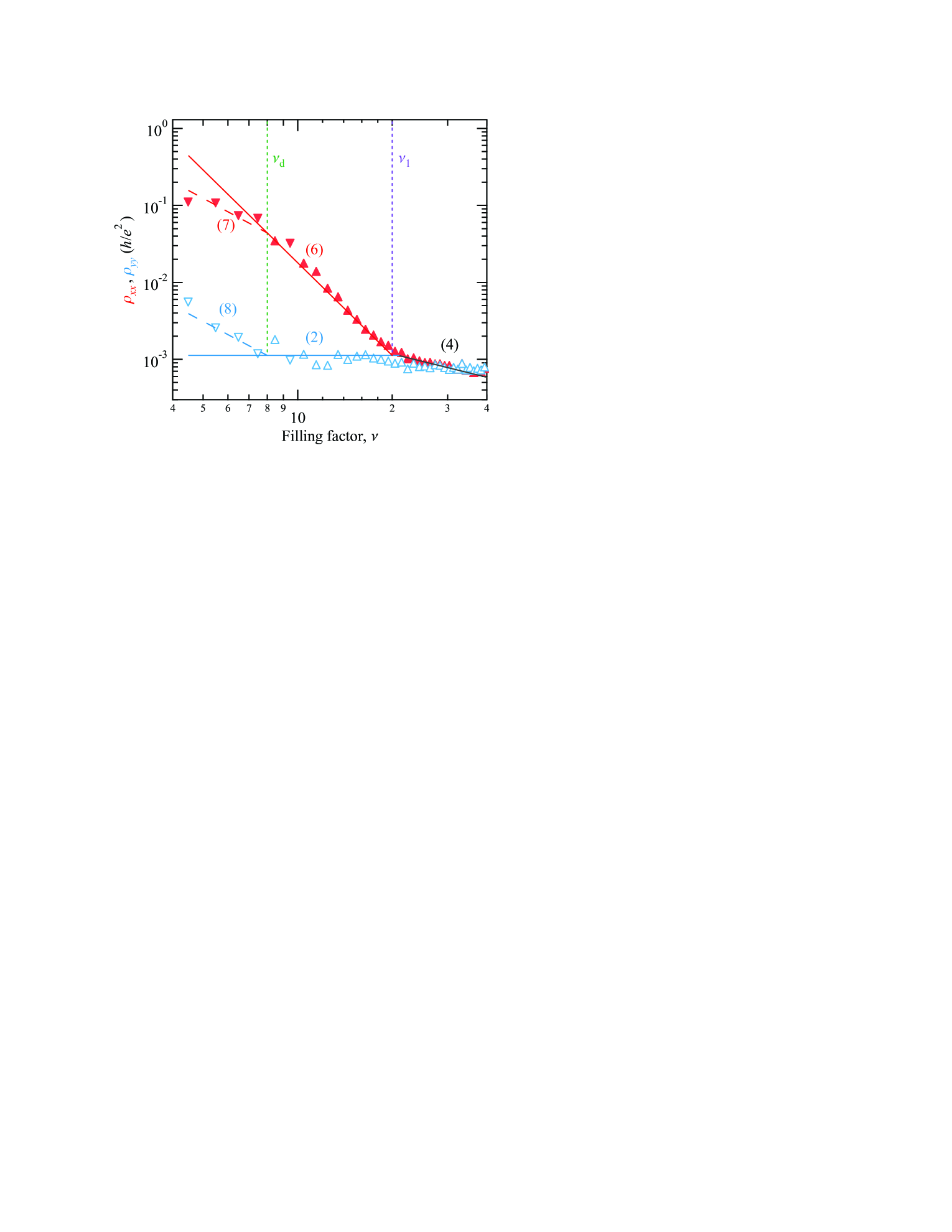

Having confirmed the existence of the hQHS phases in AlxGa1-xAs/Al0.24Ga0.76As quantum wells, we next examine the possibility for these phases to exist in ultrahigh mobility GaAs quantum wells (without alloy disorder). In such samples, the lower boundary , Eq. (1), might approach and even merge with the higher boundary , Eq. (3), eliminating the hQHS phase as a result. To test this scenario, we revisit the data obtained from sample A of Ref. Sammon et al., 2019 with , much higher than in samples used in the present study. As illustrated in Fig. 3, showing (solid triangles) and (open triangles) (not, h) as a function of the filling factor , the QHS anisotropy in this sample collapses at . Using Eq. (1), we can then estimate (not, i). With ns, Eq. (3) gives , which is very close to . Indeed, the data in Fig. 3 show that the QHS phase crosses over directly to the CZS phase, bypassing the intermediate hQHS phase.

In the QHS phase, the easy resistivity is independent and is described by , Eq. (2), while the hard resisitivty exhibits clear dependence and follows (Huang et al., 2020)

| (6) |

However, the agreement between theory and experiment breaks down at , where one observes significant deviations leading to the reduction of the anisotropy. While the nature of such reduction is unclear, it becomes more pronounced upon further cooling and might reflect a crossover to another competing ground state (Qian et al., 2017; Fu et al., 2020). We can account for the observed anisotropy reduction at lower filling factors assuming that the QHS phase has a finite concentration of dislocations separated by an average distance along stripes, where is a numerical factor. Scattering of drifting electrons by these dislocations limits their drift length by and the resistivities calculated in Refs. Sammon et al., 2019, Huang et al., 2020 need to be modified to (not, j, k)

| (7) |

| (8) |

Equations (7), (8) are plotted as dashed lines in Fig. 3. Equating Eq. (7) to Eq. (6) [or Eq. (8) to Eq. (2)], we find that the crossover to the dislocation limited transport happens at

| (9) |

With and we find . This value does not seem unreasonable and correctly accounts for the saturation of the anisotropy, (Sammon et al., 2019).

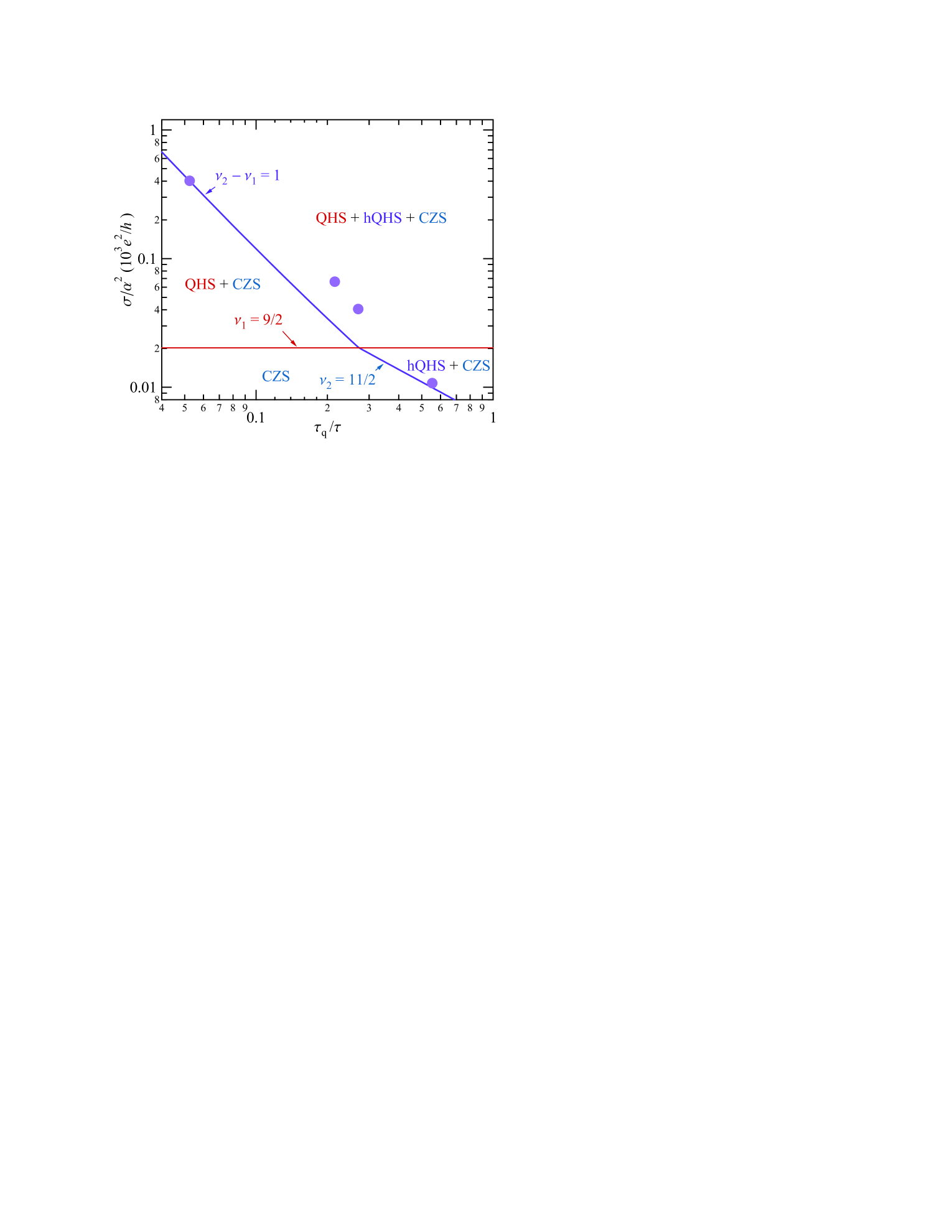

Our experimental findings in AlxGa1-xAs quantum wells (Fig. 2) and in a clean GaAs quantum well (Fig. 3) can be unified in a phase diagram shown in Fig. 4 which treats and as independent parameters. Here, the QHS phase is observed above the horizontal line corresponding to . To detect the hQHS phase, one should satisfy both and , since at least two half-integer filling factors are needed to establish the independence of the resistance (not, l). As a result, the most favorable conditions for the hQHS phase are realized at the top-right corner of the diagram. However, as demonstrated by our experiments on AlxGa1-xAs quantum wells, the hQHS can be detected at modest mobilities provided that the ratio is sufficiently high. On the other hand, this ratio is much smaller in clean GaAs quantum wells, which makes the hQHS detection difficult in such systems despite their high mobility. The phase diagram shown in Fig. 4 provides a a road map for future experiments aiming to detect the hQHS phases.

In summary, we have observed hidden quantum Hall stripe (hQHS) phases (Huang et al., 2020) forming near half-integer filling factors of AlxGa1-xAs/Al0.24Ga0.76As quantum wells with varying . These phases reside between the conventional stripe phases and the isotropic liquid phases and are characterized by isotropic resistivity that is not sensitive to the filling factor. Analysis of the experimental phase diagram reveals that the QHS density of states is smaller than predicted by the Hartree-Fock theory (Koulakov et al., 1996; Fogler et al., 1996), calling for improved theory. The unique transport characteristics of the hQHS phases should allow exploration of the stripe physics in 2D systems that, unlike GaAs, lack symmetry-breaking fields. On the other hand, ultrahigh mobility GaAs quantum wells favor conventional QHSs over hQHSs due to a shrinking filling factor range where the hQHS phases can form.

Acknowledgements.

We thank G. Jones, T. Murphy, and A. Bangura for technical support. Calculations by Y.H. were supported primarily by the National Science Foundation through the University of Minnesota MRSEC under Award Number Nos. DMR-1420013 and DMR-2011401. Experiments by X.F., Q.S., and M.Z. were supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under Award DE-SC0002567. Growth of quantum wells at Purdue University was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under Award DE-SC0006671. X.F. acknowledges the University of Minnesota Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship. A portion of this work was performed at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, which is supported by National Science Foundation Cooperative Agreement Nos. DMR-1157490 and DMR-1644779, and the State of Florida.References

- von Klitzing et al. (1980) K. von Klitzing, G. Dorda, and M. Pepper, New Method for High-Accuracy Determination of the Fine-Structure Constant Based on Quantized Hall Resistance, Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 494 (1980).

- Tsui et al. (1982) D. C. Tsui, H. L. Stormer, and A. C. Gossard, Two-Dimensional Magnetotransport in the Extreme Quantum Limit, Phys. Rev. Lett. 48, 1559 (1982).

- Koulakov et al. (1996) A. A. Koulakov, M. M. Fogler, and B. I. Shklovskii, Charge density wave in two-dimensional electron liquid in weak magnetic field, Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 499 (1996).

- Fogler et al. (1996) M. M. Fogler, A. A. Koulakov, and B. I. Shklovskii, Ground state of a two-dimensional electron liquid in a weak magnetic field, Phys. Rev. B 54, 1853 (1996).

- Moessner and Chalker (1996) R. Moessner and J. T. Chalker, Exact results for interacting electrons in high Landau levels, Phys. Rev. B 54, 5006 (1996).

- Lilly et al. (1999a) M. P. Lilly, K. B. Cooper, J. P. Eisenstein, L. N. Pfeiffer, and K. W. West, Evidence for an Anisotropic State of Two-Dimensional Electrons in High Landau Levels, Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 394 (1999a).

- Du et al. (1999) R. R. Du, D. C. Tsui, H. L. Stormer, L. N. Pfeiffer, K. W. Baldwin, and K. W. West, Strongly anisotropic transport in higher two-dimensional Landau levels, Solid State Commun. 109, 389 (1999).

- Nelson et al. (1992) S. F. Nelson, K. Ismail, J. J. Nocera, F. F. Fang, E. E. Mendez, J. O. Chu, and B. S. Meyerson, Observation of the fractional quantum Hall effect in Si/SiGe heterostructures, Appl. Phys. Lett. 61, 64 (1992).

- Kott et al. (2014) T. M. Kott, B. Hu, S. H. Brown, and B. E. Kane, Valley-degenerate two-dimensional electrons in the lowest Landau level, Phys. Rev. B 89, 041107(R) (2014).

- De Poortere et al. (2002) E. P. De Poortere, Y. P. Shkolnikov, E. Tutuc, S. J. Papadakis, M. Shayegan, E. Palm, and T. Murphy, Enhanced electron mobility and high order fractional quantum Hall states in AlAs quantum wells, Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 1583 (2002).

- Manfra et al. (2002) M. J. Manfra, N. G. Weimann, J. W. P. Hsu, L. N. Pfeiffer, K. W. West, S. Syed, H. L. Stormer, W. Pan, D. V. Lang, S. N. G. Chu, et al., High mobility AlGaN/GaN heterostructures grown by plasma-assisted molecular beam epitaxy on semi-insulating GaN templates prepared by hydride vapor phase epitaxy, J. Appl. Phys. 92, 338 (2002).

- Du et al. (2009) X. Du, I. Skachko, F. Duerr, A. Luican, and E. Y. Andrei, Fractional quantum Hall effect and insulating phase of Dirac electrons in graphene, Nature 462, 192 (2009).

- Bolotin et al. (2009) K. I. Bolotin, F. Ghahari, M. D. Shulman, H. L. Stormer, and P. Kim, Observation of the fractional quantum Hall effect in graphene, Nature 462, 196 (2009).

- Piot et al. (2010) B. A. Piot, J. Kunc, M. Potemski, D. K. Maude, C. Betthausen, A. Vogl, D. Weiss, G. Karczewski, and T. Wojtowicz, Fractional quantum Hall effect in CdTe, Phys. Rev. B 82, 081307(R) (2010).

- Tsukazaki et al. (2010) A. Tsukazaki, S. Akasaka, K. Nakahara, Y. Ohno, H. Ohno, D. Maryenko, A. Ohtomo, and M. Kawasaki, Observation of the fractional quantum Hall effect in an oxide, Nature Mat. 9, 889 (2010).

- Shi et al. (2015) Q. Shi, M. A. Zudov, C. Morrison, and M. Myronov, Spinless composite fermions in an ultrahigh-quality strained Ge quantum well, Phys. Rev. B 91, 241303(R) (2015).

- Ma et al. (2017) M. K. Ma, M. S. Hossain, K. A. Villegas Rosales, H. Deng, T. Tschirky, W. Wegscheider, and M. Shayegan, Observation of fractional quantum Hall effect in an InAs quantum well, Phys. Rev. B 96, 241301(R) (2017).

- not (a) Apart from QHSs in GaAs, electron nematic states were identified in Sr3Ru2O7 (Borzi et al., 2007), high-TC superconductors (Daou et al., 2010; Chu et al., 2010), URu2Si2 (Okazaki et al., 2011), WSe2/WS2 (Jin et al., 2020), and twisted bilayer graphene (Cao et al., 2020).

- not (b) Considering thermal and quantum fluctuations, several electron liquid crystal-like phases have also been proposed (Fradkin and Kivelson, 1999).

- Fil (2000) D. V. Fil, Piezoelectric mechanism for the orientation of stripe structures in two-dimensional electron systems, Low Temp. Phys. 26, 581 (2000).

- Koduvayur et al. (2011) S. P. Koduvayur, Y. Lyanda-Geller, S. Khlebnikov, G. Csáthy, M. J. Manfra, L. N. Pfeiffer, K. W. West, and L. P. Rokhinson, Effect of Strain on Stripe Phases in the Quantum Hall Regime, Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 016804 (2011).

- Sodemann and MacDonald (2013) I. Sodemann and A. H. MacDonald, Theory of Native Orientational Pinning in Quantum Hall Nematics, arXiv:1307.5489 (2013).

- Pollanen et al. (2015) J. Pollanen, K. B. Cooper, S. Brandsen, J. P. Eisenstein, L. N. Pfeiffer, and K. W. West, Heterostructure symmetry and the orientation of the quantum Hall nematic phases, Phys. Rev. B 92, 115410 (2015).

- not (c) QHSs were found to align along the direction in a tunable density heterostructure insulated gate field effect transistor at densities between cm-2 and cm-2 (Zhu et al., 2002) and in single heterointerface devices with cm-2 and cap thickness exceeding 1 m (Pollanen et al., 2015).

- not (d) Indeed, anisotropies emerging under the in-plane magnetic field, which is known to provide symmetry breaking (Pan et al., 1999; Lilly et al., 1999b; Jungwirth et al., 1999; Stanescu et al., 2000; Zhu et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2016b, 2017b), have been observed in ZnO (Falson et al., 2018) and AlAs (Hossain et al., 2018).

- Cooper et al. (1999) K. B. Cooper, M. P. Lilly, J. P. Eisenstein, L. N. Pfeiffer, and K. W. West, Insulating phases of two-dimensional electrons in high Landau levels: Observation of sharp thresholds to conduction, Phys. Rev. B 60, R11285 (1999).

- Eisenstein et al. (2002) J. P. Eisenstein, K. B. Cooper, L. N. Pfeiffer, and K. W. West, Insulating and Fractional Quantum Hall States in the First Excited Landau Level, Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 076801 (2002).

- Lewis et al. (2002) R. M. Lewis, P. D. Ye, L. W. Engel, D. C. Tsui, L. N. Pfeiffer, and K. W. West, Microwave Resonance of the Bubble Phases in 1/4 and 3/4 Filled High Landau Levels, Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 136804 (2002).

- Deng et al. (2012) N. Deng, A. Kumar, M. J. Manfra, L. N. Pfeiffer, K. W. West, and G. A. Csáthy, Collective Nature of the Reentrant Integer Quantum Hall States in the Second Landau Level, Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 086803 (2012).

- Rossokhaty et al. (2016) A. V. Rossokhaty, Y. Baum, J. A. Folk, J. D. Watson, G. C. Gardner, and M. J. Manfra, Electron-Hole Asymmetric Chiral Breakdown of Reentrant Quantum Hall States, Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 166805 (2016).

- Friess et al. (2017) B. Friess, Y. Peng, B. Rosenow, F. von Oppen, V. Umansky, K. von Klitzing, and J. H. Smet, Negative permittivity in bubble and stripe phases, Nature Phys. 13, 1124 (2017).

- Bennaceur et al. (2018) K. Bennaceur, C. Lupien, B. Reulet, G. Gervais, L. N. Pfeiffer, and K. W. West, Competing Charge Density Waves Probed by Nonlinear Transport and Noise in the Second and Third Landau Levels, Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 136801 (2018).

- Friess et al. (2018) B. Friess, V. Umansky, K. von Klitzing, and J. H. Smet, Current Flow in the Bubble and Stripe Phases, Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 137603 (2018).

- Fu et al. (2019) X. Fu, Q. Shi, M. A. Zudov, G. C. Gardner, J. D. Watson, and M. J. Manfra, Two- and three-electron bubbles in / quantum wells, Phys. Rev. B 99, 161402(R) (2019).

- Ro et al. (2019) D. Ro, N. Deng, J. D. Watson, M. J. Manfra, L. N. Pfeiffer, K. W. West, and G. A. Csáthy, Electron bubbles and the structure of the orbital wave function, Phys. Rev. B 99, 201111(R) (2019).

- Chen et al. (2019) S. Chen, R. Ribeiro-Palau, K. Yang, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, J. Hone, M. O. Goerbig, and C. R. Dean, Competing Fractional Quantum Hall and Electron Solid Phases in Graphene, Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 026802 (2019).

- Huang et al. (2020) Y. Huang, M. Sammon, M. A. Zudov, and B. I. Shklovskii, Isotropically conducting (hidden) quantum Hall stripe phases in a two-dimensional electron gas, Phys. Rev. B 101, 161302(R) (2020).

- MacDonald and Fisher (2000) A. H. MacDonald and M. P. A. Fisher, Quantum theory of quantum Hall smectics, Phys. Rev. B 61, 5724 (2000).

- von Oppen et al. (2000) F. von Oppen, B. I. Halperin, and A. Stern, Conductivity Tensor of Striped Quantum Hall Phases, Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 2937 (2000).

- Sammon et al. (2019) M. Sammon, X. Fu, Y. Huang, M. A. Zudov, B. I. Shklovskii, G. C. Gardner, J. D. Watson, M. J. Manfra, K. W. Baldwin, L. N. Pfeiffer, et al., Resistivity anisotropy of quantum Hall stripe phases, Phys. Rev. B 100, 241303(R) (2019).

- not (e) The mean free path along stripes limited by isotropic impurity scattering can be calculated using .

- Ando and Uemura (1974) T. Ando and Y. Uemura, Theory of Quantum Transport in a Two-Dimensional Electron System under Magnetic Fields. I. Characteristics of Level Broadening and Transport under Strong Fields, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 36, 959 (1974).

- Coleridge et al. (1994) P. T. Coleridge, P. Zawadzki, and A. S. Sachrajda, Peak values of resistivity in high-mobility quantum-Hall-effect samples, Phys. Rev. B 49, 10798 (1994).

- not (f) Our estimates show that reaches a maximum of 6 at %.

- Gardner et al. (2013) G. C. Gardner, J. D. Watson, S. Mondal, N. Deng, G. A. Csáthy, and M. J. Manfra, Growth and electrical characterization of Al0.24Ga0.76As/AlxGa1-xAs/ Al0.24Ga0.76As modulation-doped quantum wells with extremely low x, Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 252103 (2013).

- not (g) In general, should be modified by a factor , where is a parameter depending on the nature of scattering (Sammon et al., 2019). In samples without alloy disorder, decreases with where () is the concentration of Coulomb impurities in the barrier (quantum well), starting from at (Sammon et al., 2019), whereas in samples where scattering is dominated by alloy disorder (Huang et al., 2020). While we estimate in our samples A and B, we will assume for simplicity.

- Shi (2017) Q. Shi, Magnetotransport in quantum Hall systems at high Landau levels, Ph.D. thesis, University of Minnesota, 2017.

- Raikh and Shahbazyan (1993) M. E. Raikh and T. V. Shahbazyan, High Landau levels in a smooth random potential for two-dimensional electrons, Phys. Rev. B 47, 1522 (1993).

- Mirlin et al. (1996) A. D. Mirlin, E. Altshuler, and P. Wölfle, Quasiclassical approach to impurity effect on magnetooscillations in 2D metals, Ann. Phys. (N.Y.) 508, 281 (1996).

- Shi et al. (2016a) Q. Shi, S. A. Studenikin, M. A. Zudov, K. W. Baldwin, L. N. Pfeiffer, and K. W. West, Microwave photoresistance in an ultra-high-quality GaAs quantum well, Phys. Rev. B 93, 121305(R) (2016a).

- Shi et al. (2017a) Q. Shi, M. A. Zudov, I. A. Dmitriev, K. W. Baldwin, L. N. Pfeiffer, and K. W. West, Fine structure of high-power microwave-induced resistance oscillations, Phys. Rev. B 95, 041403(R) (2017a).

- Zudov et al. (2017) M. A. Zudov, I. A. Dmitriev, B. Friess, Q. Shi, V. Umansky, K. von Klitzing, and J. Smet, Hall field-induced resistance oscillations in a tunable-density GaAs quantum well, Phys. Rev. B 96, 121301(R) (2017).

- Zudov et al. (2001) M. A. Zudov, R. R. Du, J. A. Simmons, and J. L. Reno, Shubnikov–de Haas-like oscillations in millimeterwave photoconductivity in a high-mobility two-dimensional electron gas, Phys. Rev. B 64, 201311(R) (2001).

- Ye et al. (2001) P. D. Ye, L. W. Engel, D. C. Tsui, J. A. Simmons, J. R. Wendt, G. A. Vawter, and J. L. Reno, Giant microwave photoresistance of two-dimensional electron gas, Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 2193 (2001).

- Dmitriev et al. (2012) I. A. Dmitriev, A. D. Mirlin, D. G. Polyakov, and M. A. Zudov, Nonequilibrium phenomena in high Landau levels, Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 1709 (2012).

- Yang et al. (2002) C. L. Yang, J. Zhang, R. R. Du, J. A. Simmons, and J. L. Reno, Zener Tunneling Between Landau Orbits in a High-Mobility Two-Dimensional Electron Gas, Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 076801 (2002).

- Zhang et al. (2007) W. Zhang, H.-S. Chiang, M. A. Zudov, L. N. Pfeiffer, and K. W. West, Magnetotransport in a two-dimensional electron system in dc electric fields, Phys. Rev. B 75, 041304(R) (2007).

- Vavilov et al. (2007) M. G. Vavilov, I. L. Aleiner, and L. I. Glazman, Nonlinear resistivity of a two-dimensional electron gas in a magnetic field, Phys. Rev. B 76, 115331 (2007).

- Coleridge et al. (1996) P. Coleridge, M. Hayne, P. Zawadzki, and A. Sachrajda, Effective masses in high-mobility 2D electron gas structures, Surf. Sci. 361, 560 (1996).

- Tan et al. (2005) Y.-W. Tan, J. Zhu, H. L. Stormer, L. N. Pfeiffer, K. W. Baldwin, and K. W. West, Measurements of the Density-Dependent Many-Body Electron Mass in Two Dimensional GaAs/AlGaAs Heterostructures, Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 016405 (2005).

- Hatke et al. (2013) A. T. Hatke, M. A. Zudov, J. D. Watson, M. J. Manfra, L. N. Pfeiffer, and K. W. West, Evidence for effective mass reduction in GaAs/AlGaAs quantum wells, Phys. Rev. B 87, 161307(R) (2013).

- Shchepetilnikov et al. (2017) A. V. Shchepetilnikov, D. D. Frolov, Y. A. Nefyodov, I. V. Kukushkin, and S. Schmult, Renormalization of the effective mass deduced from the period of microwave-induced resistance oscillations in GaAs/AlGaAs heterostructures, Phys. Rev. B 95, 161305(R) (2017).

- Fu et al. (2017) X. Fu, Q. A. Ebner, Q. Shi, M. A. Zudov, Q. Qian, J. D. Watson, and M. J. Manfra, Microwave-induced resistance oscillations in a back-gated GaAs quantum well, Phys. Rev. B 95, 235415 (2017).

- not (h) The resistivities represented by () were obtained from and (Simon, 1999) ( and theoretical resistivity product MacDonald and Fisher (2000); von Oppen et al. (2000)); see Ref. Sammon et al., 2019 for details.

- not (i) The analysis of the anisotropy ratio in this sample (Sammon et al., 2019) with theoretical value of leads to (see also Ref. not, g) and a ratio of concentrations of Coulomb impurities in the spacer to that in the quantum well , , much larger than estimated in Ref. Sammon et al., 2018. Our present experiments, however, suggest lower value of , leading to larger and restoring the agreement with Ref. Sammon et al., 2018. Larger can also result from interface roughness scattering, which was not theoretically considered in Ref. Sammon et al., 2018.

- Qian et al. (2017) Q. Qian, J. Nakamura, S. Fallahi, G. C. Gardner, and M. J. Manfra, Possible nematic to smectic phase transition in a two-dimensional electron gas at half-filling, Nature Commun. 8, 1536 (2017).

- Fu et al. (2020) X. Fu, Q. Shi, M. A. Zudov, G. C. Gardner, J. D. Watson, M. J. Manfra, K. W. Baldwin, L. N. Pfeiffer, and K. W. West, Anomalous Nematic States in High Half-filled Landau Levels, Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 067601 (2020).

- not (j) With , the resistivity in units of is , where and () is the mean free path along the () direction. Without dislocations, , , and , while . With dislocations, , i.e., , and .

- not (k) Eqs (7) and (8) can be obtained via replacement of hopping time of electrons between neighboring stripes by , where is the drift velocity of electron along the stripe.

- not (l) The approximate condition for the hQHS phase detection is .

- Borzi et al. (2007) R. A. Borzi, S. A. Grigera, J. Farrell, R. S. Perry, S. J. S. Lister, S. L. Lee, D. A. Tennant, Y. Maeno, and A. P. Mackenzie, Formation of a Nematic Fluid at High Fields in Sr3Ru2O7, Science 315, 214 (2007).

- Daou et al. (2010) R. Daou, J. Chang, D. LeBoeuf, O. Cyr-Choiniere, F. Laliberte, N. Doiron-Leyraud, B. J. Ramshaw, R. Liang, D. A. Bonn, W. N. Hardy, et al., Broken rotational symmetry in the pseudogap phase of a high-Tc superconductor, Nature 463, 519 (2010).

- Chu et al. (2010) J.-H. Chu, J. G. Analytis, K. De Greve, P. L. McMahon, Z. Islam, Y. Yamamoto, and I. R. Fisher, In-Plane Resistivity Anisotropy in an Underdoped Iron Arsenide Superconductor, Science 329, 824 (2010).

- Okazaki et al. (2011) R. Okazaki, T. Shibauchi, H. J. Shi, Y. Haga, T. D. Matsuda, E. Yamamoto, Y. Onuki, H. Ikeda, and Y. Matsuda, Rotational Symmetry Breaking in the Hidden-Order Phase of URu2Si2, Science 331, 439 (2011).

- Jin et al. (2020) C. Jin, Z. Tao, T. Li, Y. Xu, Y. Tang, J. Zhu, S. Liu, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, J. C. Hone, et al., Stripe phases in WSe2/WS2 moir superlattices, arXiv:2007.12068.

- Cao et al. (2020) Y. Cao, D. Rodan-Legrain, J. M. Park, F. N. Yuan, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, R. M. Fernandes, L. Fu, and P. Jarillo-Herrero, Nematicity and Competing Orders in Superconducting Magic-Angle Graphene, arXiv:2004.04148.

- Fradkin and Kivelson (1999) E. Fradkin and S. A. Kivelson, Liquid-crystal phases of quantum Hall systems, Phys. Rev. B 59, 8065 (1999).

- Zhu et al. (2002) J. Zhu, W. Pan, H. L. Stormer, L. N. Pfeiffer, and K. W. West, Density-Induced Interchange of Anisotropy Axes at Half-Filled High Landau Levels, Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 116803 (2002).

- Pan et al. (1999) W. Pan, R. R. Du, H. L. Stormer, D. C. Tsui, L. N. Pfeiffer, K. W. Baldwin, and K. W. West, Strongly Anisotropic Electronic Transport at Landau Level Filling Factor under a Tilted Magnetic Field, Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 820 (1999).

- Lilly et al. (1999b) M. P. Lilly, K. B. Cooper, J. P. Eisenstein, L. N. Pfeiffer, and K. W. West, Anisotropic States of Two-Dimensional Electron Systems in High Landau Levels: Effect of an In-Plane Magnetic Field, Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 824 (1999b).

- Jungwirth et al. (1999) T. Jungwirth, A. H. MacDonald, L. Smrčka, and S. M. Girvin, Field-tilt anisotropy energy in quantum Hall stripe states, Phys. Rev. B 60, 15574 (1999).

- Stanescu et al. (2000) T. D. Stanescu, I. Martin, and P. Phillips, Finite-Temperature Density Instability at High Landau Level Occupancy, Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 1288 (2000).

- Zhu et al. (2009) H. Zhu, G. Sambandamurthy, L. W. Engel, D. C. Tsui, L. N. Pfeiffer, and K. W. West, Pinning Mode Resonances of 2D Electron Stripe Phases: Effect of an In-Plane Magnetic Field, Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 136804 (2009).

- Shi et al. (2016b) Q. Shi, M. A. Zudov, J. D. Watson, G. C. Gardner, and M. J. Manfra, Evidence for a new symmetry breaking mechanism reorienting quantum Hall nematics, Phys. Rev. B 93, 121411(R) (2016b).

- Shi et al. (2017b) Q. Shi, M. A. Zudov, Q. Qian, J. D. Watson, and M. J. Manfra, Effect of density on quantum Hall stripe orientation in tilted magnetic fields, Phys. Rev. B 95, 161303(R) (2017b).

- Falson et al. (2018) J. Falson, D. Tabrea, D. Zhang, I. Sodemann, Y. Kozuka, A. Tsukazaki, M. Kawasaki, K. von Klitzing, and J. H. Smet, A cascade of phase transitions in an orbitally mixed half-filled Landau level, Science Advances 4 (2018).

- Hossain et al. (2018) M. S. Hossain, M. A. Mueed, M. K. Ma, Y. J. Chung, L. N. Pfeiffer, K. W. West, K. W. Baldwin, and M. Shayegan, Anomalous coupling between magnetic and nematic orders in quantum Hall systems, Phys. Rev. B 98, 081109(R) (2018).

- Simon (1999) S. H. Simon, Comment on “Evidence for an Anisotropic State of Two-Dimensional Electrons in High Landau Levels”, Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 4223 (1999).

- Sammon et al. (2018) M. Sammon, M. A. Zudov, and B. I. Shklovskii, Mobility and quantum mobility of modern GaAs/AlGaAs heterostructures, Phys. Rev. Materials 2, 064604 (2018).