Identifiability and Observability Analysis for Epidemiological Models: Insights on the SIRS Model

Abstract

The problems of observability and identifiability have been of great interest as previous steps to estimating parameters and initial conditions of dynamical systems to which some known data (observations) are associated. While most works focus on linear and polynomial/rational systems of ODEs, general nonlinear systems have received far less attention and, to the best of our knowledge, no general constructive methodology has been proposed to assess and guarantee parameter and state recoverability in this context. We consider a class of systems of parameterized nonlinear ODEs and some observations, and study if a system of this class is observable, identifiable or jointly observable-identifiable; our goal is to identify its parameters and/or reconstruct the initial condition from the data. To achieve this, we introduce a family of efficient and fully constructive procedures that allow recoverability of the unknowns with low computational cost and address the aforementioned gap. Each procedure is tailored to different observational scenarios and based on the resolution of linear systems. As a case study, we apply these procedures to several epidemic models, with a detailed focus on the SIRS model, demonstrating its joined observability-identifiability when only a portion of the infected individuals is measured, a scenario that has not been studied before. In contrast, for the same observations, the SIR model is observable and identifiable, but not jointly observable-identifiable. This distinction allows us to introduce a novel approach to discriminating between different epidemiological models (SIR vs. SIRS) from short-time data. For these two models, we illustrate the theoretical results through some numerical experiments, validating the approach and highlighting its practical applicability to real-world scenarios.

Key words: Nonlinear epidemiological models; Parameter identifiability; State observability; Joined observability-identifiability; SIRS model analysis; Epidemiological model discrimination; Epidemic data reconstruction.

1 Introduction

Mathematical modeling has been widely used for studying epidemics for a long time. Some of the most popular models in epidemics generated by infectious diseases are compartmental models, whose theory was set up in the early 1900s (see [40]), and have been regularly used since then to estimate the dynamics of different diseases (for example, influenza [7, 11], tuberculosis [20, 36], Ebola [17, 61], or vector-transmitted diseases such as malaria [62], dengue fever or the Zika virus [8, 21]), with a significant surge in applications in recent years due to the COVID-19 pandemic (see, for example, [2, 6, 33, 54, 56]). These models are usually deterministic systems of nonlinear ODEs, which include the class of systems that we are going to address from now on.

Given a disease and some information on the different biological processes that are involved, we need to set up a model that captures the most important features of its dynamics, being careful not to complexify it up to a point that may result intractable from a mathematical perspective. To these dynamical models there are associated data, available in the literature (e.g., parameter values) or collected over time (e.g., how many people are hospitalized or vaccinated at certain dates). This information is partial most of the time, in the sense that they are related to some of the parameters and state variables of the model, but rarely to all of them. For instance, the sizes of susceptible or asymptomatic compartments are often hard or even impossible to measure (they are hidden variables), and the transmission rate of a new virus is often not known in advance.

Once we have settled a model and know some information about the parameters and compartments, a question arises: Can we uniquely reconstruct all the unknowns of the model from partial observations? The ability to accurately reconstruct key aspects of disease dynamics from observed data is fundamental to understand epidemic trajectories and design effective control strategies. Thus, determining whether the parameters can be uniquely identified or the states can be precisely reconstructed from available data is essential. We thus face an inverse problem. Such identification and state reconstruction problems are often met in automatic control for linear and nonlinear dynamics. Although many successful applications have been recorded in aeronautics, automotive, electronics, or chemistry, among other domains, very few has been investigated for epidemiological models. Moreover, despite substantial research addressing these questions, significant challenges remain, particularly in nonlinear models, where exact reconstruction of parameters and states is often elusive and requires sophisticated analytical approaches.

In this context, the determination of a feasible set of parameters and an initial condition that align with observed data falls into two key problems: The parameter identification problem and the state observation problem in automatic control literature. These have been addressed in many different ways (see, for example, [10, 12, 29, 14, 60, 51, 64]). However, before attempting to determine these unknowns, it is crucial to assess the extent of recoverable information from the available epidemic data. For example, can we determine the disease contact rate if we know the data of hospitalized people? What about the loss of immunity rate? How many people were infected when the data started to be reported? Of course, these are not issues related only to epidemiological models. In general, given a phenomenon we want to model (e.g., physical, biological, or mechanical), we will have some parameters, a state vector (in the epidemiological case, these states are the size of the population in each compartment, or a portion of this size), and some observed data of this phenomenon (also called measurements, outputs of the model, or signals [38]). The theories of identifiability and observability provide the foundation for addressing these questions. Let us briefly introduce these concepts.

Identifiability theory is the one in charge of deciding, given an initial condition and some observed data, if we can determine univocally all the unknown parameters that govern our system. If it is not possible, we can possibly recover them partially (some of them or some combination of them).

Observability theory is the one in charge of deciding, given the parameters and some observed data, if we can recover the initial condition; in other words, if there exists a unique initial condition such that the solution starting from this initial condition matches our observations, and hence we can distinguish different states from partial measurements of the state vector.

If one is interested in both identifying and observing the system, i.e., if it is jointly observable-identifiable (see [13]) it is common to extend the system by considering the parameters as part of the state vector (with a null dynamics), and then considering the observation problem of this extended system. The most commonly used technique to decide whether a system is observable or not is the Hermann-Krener condition, or Observability Rank Condition, that consists in studying the separability of a set composed by the observations and its Lie derivatives with respect to the vector field of the system (see [31]); this computation may be sometimes simplified by exploiting symmetries or groups of invariance of the system (in particular, for mechanical and/or robotics systems, see e.g. [48]). If we conclude our system is observable, then we can make use of several techniques that may help us estimate practically the unknowns; in particular, to perform this task, we can try to construct a state observer, as for example the Luenberger observer [47], high-gains observers [24], or the Kalman filter [37]. These techniques aim to estimate the state vector at a certain speed with a certain accuracy, minimizing the estimation error at a given time, such that it is usually asymptotically null, but do not guarantee exact reconstruction. Sometimes, however, one can treat the system algebraically and try to reconstruct exactly the unknowns in terms of, for example, the derivatives of the data whenever they exist and are known (or can be computed) perfectly (see [13, Chapter 3]).

The theories of identifiability and observability extend beyond the epidemiological context and are relevant to any phenomena modeled through ODE systems with measurable outputs or functions of the states (see [3, 4, 25, 32, 34, 65]). Indeed, there is few literature about studying the joined observability-identifiability of epidemiological models (see [13], which is a survey that can be used as a textbook about this topic, and [19], [30], and [49]).

Several works have emphasized the importance of initial conditions for identifying the parameters of a general system, and not every initial condition is suitable, i.e., some initial conditions can produce the same output when considering different parameters (see, e.g., [15], [59]). While there are fields where one can perform different experiments with chosen initial conditions in order to identify the parameters (see, e.g., [15, 35]), in disciplines such as Epidemiology this is not possible, and hence we need to study which initial conditions are not suitable, and if we can avoid them. In this paper, we build on the theory developed in [44], and extend the results by considering the existence of non-suitable initial conditions which are dependent on the parameters.

On the other hand, most of the research carried out in observability and identifiability of nonlinear dynamics is centered on polynomial and rational systems of equations (see, e.g., [16, 26, 28, 27, 59]), and the study of nonlinear, non-rational systems is scarce (see the survey [1]). In rational systems, the goal is typically finding the input-output (IO) equations in order to determine if the parameters are identifiable. These are structural equations of the system under study, which relate the parameters, the outputs and their derivatives, and their inputs (if any). However, we consider that, in these works, there lacks a direct, unified argument to conclude that these parameters can be effectively recovered from these equations. In [44], general nonlinearities are considered, and it advances the state of the art by minimizing reliance on high-order derivatives, improving robustness with respect to noisy and sparse datasets, and offering novel techniques to address joined observability-identifiability in nonlinear systems of ODEs. Moreover, this lacking argument is also covered by considering an assumption about linear independence of functions of the observations and their derivatives. This assumption of linear independence was already tackled in [15] to prove identifiability alone, however, it is framed in the case of rational systems and it assumes knowledge of initial conditions and having data at the initial time; these last assumptions are not feasible in some fields such as Epidemiology. It is as well mentioned in [53] for linear ODE systems, which do not cover epidemiological models either.

This paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we motivate through the SIRS model the application of this framework to epidemiological models. Then, in Section 3, we revisit and extend the theoretical part presented in [44], and establish different constructive algorithms to recover the parameters and/or initial condition. We also extend the theory to incorporate higher-order derivatives, and highlight that this framework can be extended to scenarios with piecewise constant parameters, provided that the time instants of parameter changes are known or the time intervals with constant values are large enough.

In Section 4, we validate this approach by applying it to the SIRS model, proving joined observability-identifiability under partial observations of the infected compartment, an example that we have not seen considered in the literature. We will observe that in this case it is crucial considering initial conditions in parameter-dependent sets. Furthermore, although this is a rational model which can be studied through classical techniques, using our methodology allows for early-stage model discrimination between SIR and SIRS structures, enabling the detection of immunity loss directly from observational data. This distinction addresses a key gap in the literature, to the best of our knowledge, where theoretical studies often overlook model selection based on limited data. After this, we present in Section 5 other epidemiological examples to highlight the interest of the proposed approach. Finally, we perform in Section 6 different numerical experiments using the SIRS and the SIR models in two different scenarios that illustrate our approach.

2 Motivating framework: Insights from the SIRS model

Compartmental models, such as the SIRS model, strongly depend on real data to determine their parameters and the current state of the disease. These data are typically scarce and noisy, making it crucial to develop methods to estimate the unknown parameters and/or initial condition from partial observations. For this, we are going to follow two different approaches, depending on the type of available data: identifiability and observability, both formally defined in Section 3.

Let us consider the following classical SIRS model together with an output, given by an unknown fraction of the infected individuals at time , represented by :

| (1) |

This model is particularly relevant for understanding the dynamics of diseases such as influenza of some coronaviruses. It is also of interest in different realistic situations, such as performing random tests among the population, or considering that a fraction of the infectious people are asymptomatic and hence we do not measure those cases, where the parameter is typically unknown. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the main challenges when studying the prevalence of the disease was estimating the asymptomatic cases, whereas governments also conducted randomized testing to estimate this prevalence (see, for example, [55]).

Given this model, we are interested in knowing whether it is identifiable, observable or jointly observable-identifiable. To address this, in Section 3, we revisit and extend the general framework of [44]. The presented SIRS model with output fits within the class of systems presented in Section 3 and serves as a motivating example. Indeed, in Section 4 we make use of this approach to prove its joined observability-identifiability when . Moreover, we compare these results to those obtained for the (a priori simpler) SIR model, which can be considered as a limiting case of the SIRS model with , considering the same observational data (i.e., a fraction of infected individuals). Our analysis reveals that the SIR model is both observable and identifiable, but lacks joined observability-identifiability, highlighting a key distinction between these two models that allows us to distinguish them in an early stage. We will illustrate this difference through the numerical tests presented in Section 6.

3 A general framework

In this section, we extend the general framework established in [44] for analyzing observability, identifiability and joined observability-identifiability of dynamical systems, particularly focusing on systems modeled by autonomous differential equations with unknown parameters. We provide conditions under which the parameters and/or initial condition of such systems can be uniquely determined from observations of the system’s output. To this end, we first introduce the mathematical formulation of the model and provide formal definitions of the key concepts: Identifiability, observability, and joined observability-identifiability. Unlike in [44], when discussing identifiability, we will consider the possibility of parameter-dependent initial conditions that impede identifiability; this is a typical situation in epidemiological models. Additionally, we revisit some concepts on Lie derivatives that are instrumental in the theoretical analysis. Building on this foundation, we extend the key results from [44], taking into account these parameter-dependent initial conditions, that enable to establish different constructive methodologies to recover the initial condition and/or the parameters, whenever possible. Moreover, we present a third approach using higher-order derivatives to recover the unknowns in cases where the system is proven to be jointly observable-identifiable.

3.1 Mathematical formulation and definitions

Consider a phenomenon that can be modeled by a system of first order autonomous differential equations, which depends on some unknown parameter vector . Together with an initial condition , we assume the model provides some output , described by a suitable function . The mathematical formulation of the model and its output is given by

| (2) |

where is a known function of which is locally Lipschitz-continuous w.r.t. (to guarantee uniqueness of solutions) and continuous w.r.t. ; are the constant parameters of the system; is a positively invariant set with respect to the system of ODEs of System (2), for any (i.e., solutions starting in remain in during all its definition time); denotes the unique solution of the system of ODEs of System (2) with initial condition and we assume it is globally defined, i.e., ; and the output , , is described by some known function .

We aim to answer one question: given the output for certain , can we uniquely determine (given ), (given ) or both of them?

We present now formal definitions of the identifiability and observability concepts mentioned in the Introduction. As previously mentioned, some parameter-dependent initial conditions may not allow to distinguish different parameters. Hence, we will consider, for each , a subset positively invariant w.r.t. the ODE system in System (2), and the set . Notice that, if , for each , then .

Definition 1 (Identifiability in a time set).

System (2) is identifiable on in with initial conditions consistent with the family if, for any , for any , a different produces a different output at some time , i.e.,

Equivalently, if , for all and any , then . Moreover, if , for each , we say that System (2) is identifiable on in with initial conditions in .

A typical initial condition which may not allow identifiability are the equilibrium points that depend on the parameters, in the case that different parameter vectors generate the same constant observation. This phenomenon will be illustrated in Section 4.

Definition 2 (Observability in a time set).

System (2) is observable on in with parameters in whether, for any , any two different produce a different output at some time , i.e.,

Equivalently, if , for all and any , then .

Definition 3 (Identifiability).

Definition 4 (Observability).

Notice that identifiability (resp. observability) in a time set implies identifiability (resp. observability) in any time set such that . However, the converse is not necessarily true, as demonstrated by the following examples.

Example 1. Consider the following system:

| (3) |

where is unknown. Let , , be the positively invariant set w.r.t. the ODE given in (3), , , and (which is Lipschitz-continuous w.r.t. and continuous w.r.t. ). The unique solution of the ODE is , The system is identifiable on in with initial conditions in , since, for any , considering different , we have that

for all . However, if , and , with , then

for any , and hence the system is not identifiable on in with initial conditions in . ∎

Example 2. We consider the same case as the one shown in Example 4. The system is observable on in with parameters in , since, for any , considering different , we have that

for all . However, if and , with , then

for any , , and hence the system is not observable on in with parameters in . ∎

A natural extension of this framework consists in treating the parameters as part of the states of an augmented system. If one extends the dynamics with , then both the identifiability and observability properties can be studied as a particular case of observability in higher dimension: If the extended system is observable, then the original system is both observable and identifiable. However, the reverse implication is not generally true. This is related to the joined observability-identifiability of a system (see [13, 63]).

We are now going to consider that we need to recover both and .

Definition 5 (Joined observability-identifiability in a time set).

System (2) is jointly observable-identifiable on in if, for any , a different produces a different output at some time , i.e.,

Equivalently, if for all , this implies that and .

Definition 6 (Joined observability-identifiability).

Furthermore, joined observability-identifiability in a time set implies joined observability-identifiability in any time set such that .

Note that recovering the parameters and initial condition from the data up to time is equivalent to reconstructing the parameters and state at current time , because the dynamics is deterministic and reversible.

Our main focus will be on joined observability-identifiability; however, we will present the results in a way that they may be applicable separately to observability or identifiability. In particular, as commented before, it is clear that joined observability-identifiability implies both observability and identifiability independently.

In the following, we recall the well-known concept of Lie derivative, which is commonly used for studying observability and identifiability. We briefly review it here for completeness.

3.2 About Lie derivatives

Let . Consider , for some , and the map

where and, if , is the Lie derivative of with respect to the vector field , i.e., for any ,

where is the Jacobian matrix of . In particular, if is a solution of

| (4) |

such that is positively invariant with respect to this system, then, for any ,

| (5) |

Then,

| (6) |

If , we also define , for , by recursion as follows:

Lemma 1.

Let , , , and consider System (4), where and is positively invariant with respect to the system. Then, for , ,

Proof.

Let us now, given , denote and , and assume , for some . Then, . Indeed, for all ,

By Lemma 1, we have, for all and ,

where we denote , when . Then, denoting , define as

Roughly speaking, the Lie derivatives of an output of the considered system allow to express the time derivatives of the output not as functions of time, but as functions of the state vector of the system.

In the following, we denote , and as , and , respectively, when the context is clear.

Let us now present our main results along with the algorithms to recover both the parameters and the initial condition.

3.3 Main results

We revisit and extend some results from [44] to establish sufficient hypotheses for System (2) to be observable, identifiable or jointly observable-identifiable. These results generalize classical approaches (see [44] for a thorough review).

We start recalling a classical result on observability based on Lie derivatives ([13, 24, 31, 47]). This result is of particular interest in the nonlinear context (for which the Cayley-Hamilton theorem is not available, see [13, Section 2.2]). We present the result and a short proof adapted to our framework.

Theorem 1.

Proof.

Given , let such that

Given , let and Since is positively invariant w.r.t. the ODE system given in (2), , . Then,

Notice that and is non-empty. This implies that

where . In particular, , , . Then,

Since is injective in , for any , and due to the positive invariance, this implies that , i.e., . Due to the uniqueness of solutions of System (2), this implies that .

Hence, System (2) is observable on in any with parameters in . ∎

For , , we define the notation

and may use the shorthand notation when there is no ambiguity.

The following is the main result in [44], adapted to Definition 1, which provides a sufficient condition to ensure recoverability of parameters.

Theorem 2.

Let , for some 111We use a different notation with respect to Theorem 1 to explicitly state that these orders may be different., , and , , for any . Consider such that, for all , , for all . Let be such that every connected component of contains an open interval. Assume there exist and , for some , satisfying:

-

(C1)

and , with , satisfy that

(7) in , for all , for any ,

-

(C2)

is injective, and

-

(C3)

for any , , we have that , , are linearly independent functions with respect to .

Then, System (2) is identifiable on in with initial conditions consistent with the family .

Proof.

Given , , let such that

i.e.

Then, since every connected part of contains some open interval, this implies that

Since

in , we obtain, from (7),

in for every . Given the linear independence of , , in , for every , , then . Since is injective, we have . Hence, System (2) is identifiable on in with initial conditions consistent with the family . ∎

Remark 1.

It is important to remark that Theorem 2 gives only sufficient conditions for identifiability, but in Section 4.2 we will see an example of a system which is identifiable and does not satisfy these conditions. Nevertheless, as we will see in Algorithm 3, the conditions presented in Theorems 1 and 2 will allow us to have joined observability-identifiability of System (2). In [15, Proposition 2.1], the authors propose a result similar to Theorem 2, giving conditions for it to be also necessary, in a context of rational equations and under the availability of observations at initial time.

Therefore, given a system of ODEs, along with some (partial) observations, we can check the hypotheses in Theorems 1 and 2 in order to determine the observability, identifiability or joined observability-identifiability of our model and recover the initial condition and parameter vector. Notice that we need to be careful when choosing the positively invariant sets we are going to work with, so that the hypotheses mentioned above are satisfied. Next, we present a theorem which shows that, under certain conditions, given in some time set, we can recover .

Theorem 3.

For each , let be positively invariant with respect to the ODE system in (2). Let . Assume we know in , such that every connected component contains an open interval. If the hypotheses of Theorems 1 and 2 are satisfied, then System (2) is jointly observable-identifiable in and we can reconstruct the pair univocally using the values of and its derivatives at, at most, suitable values of .

Proof.

Let , , . By hypothesis, are linearly independent in , for each . Then, for every , there exist (see [44, Lemma 1]) different time instants such that

Then, there exists a unique solution to

| (8) |

Attending to (7), it satisfies , . Since is injective, such that , we can recover our original parameter vector

Finally, to recover , take some time , which can be some . Since is injective in , there exists a unique such that

noticing that . Since it is unique, it must satisfy . We can recover integrating backwards the ODE system in System (2) knowing , and (since is Lipschitz in and, in particular, in positively invariant w.r.t. the ODE system of (2)). If , we directly choose .

This is, we have recovered and from the data univocally knowing in , using its value and the value of its derivatives at (at most) different time instants. ∎

In the following Algorithm 3, we present a procedure to recover the unknowns given some observations, based on the proof of Theorem 3.

Algorithm 1. Assume that we know (satisfying System (2)) in , such that every connected of component contains an open interval, and and/or are unknown. The procedure to recover the unknowns is the following:

- Step 1.

- Step 2.

-

Step 3.

If we have defined and , set , for all . If we have only defined , redefine . If we have only defined , set , for every .

-

Step 4.

If is unknown, for each , find different time instants such that

where .

-

Step 5.

If is unknown, for each , solve the following linear system which, according to Step 4, has a unique solution :

(9) where .

- Step 6.

-

Step 7.

If is unknown, choose some (which can be some if we performed Step 4) and solve for the equation

Note: We are taking into account that is injective in and, in particular, in , for any , according to Step 1, and , for all , .

-

Step 8.

If is unknown and , integrate backwards System (2) from to with initial condition , knowing , in order to recover .

Recall that the time instants required in Step 4 may be anywhere in , and hence may be difficult to find in practice. Nevertheless, in Lemma (2) we give sufficient hypotheses such that System (2) is identifiable in any semi-open interval ; this will imply that we will be able to choose this set of time instants in any of these semi-open intervals. Then, an analogous procedure to this one will be presented in Algorithm 3.

Remark 2.

Notice that, in order to be able to recover following the procedure in Step 4 of Algorithm 3, for each set , , we need to find different suitable time instants. However, some of these time instants may coincide among different sets of linearly independent functions. Thus, the number of different time instants we need to find is between and , along maybe with , which we can use to recover the initial condition if and could be one of the other time instants.

Recall, moreover, that we do not necessarily need , for all , but it would be sufficient having the values of and its derivatives at the aforementioned different time instants, where the order of the derivatives that we need are the same as for Algorithm 3.

Note: Although this idea of choosing a number of suitable time instants has already been commented in [59, Remark 3] and [42], no proof nor more detail is given.

Lemma 2.

Proof.

Given , , let such that

i.e.,

Then,

Since, for any , and , the functions are analytic in , then the function

is also analytic in . Given that ,

in , for any . Since

in , we have

in . This implies that, for every ,

in . Due to the analyticity of , , in , is also analytic in . If in , then in ([58, Theorem 8.5]). Therefore, since , , are linearly independent in , they are also linearly independent in , and hence, for to be 0 in , for all , we need . Since is injective, this implies .

If is connected, , , analytic in implies is analytic in , and in implies in (if is not connected, we can only assure in the connected component containing ). Thus, we conclude analogously using the linear independence of , , in . Hence, System (2) is identifiable on in any with initial conditions consistent with the family . ∎

Taking into account Theorem 1 and Lemma 2, we present a lemma that shows that we may recover and knowing only in some .

Lemma 3.

For each , let be positively invariant with respect to the ODE system in (2). Let . Assume we know in some . If the hypotheses of Theorem 1 and Lemma 2 are satisfied for some such that , then System (2) is jointly observable-identifiable in , and we can reconstruct univocally using the values of and its derivatives at a finite amount of suitable values in . In particular, the required number of time points is between and .

Proof.

We recover analogously to the proof of Theorem 3. We only need to see that, given , since the functions , , are linearly independent in some and analytic in , they are linearly independent in . Given , assume that , , are linearly dependent in , i.e., there exist not all of them null such that,

Since , , are analytic in , then so it is . This implies that (see [58, Theorem 8.5]) in and, thus, , , are linearly dependent in , and hence in , which is a contradiction.

Moreover, if is connected, it is enough asking for , , analytic in , since, then, so it is . Therefore, in connected implies (see [58, Theorem 8.5]) that in , which leads to the same contradiction. Therefore, for each , the functions , with , , are linearly independent in and we can conclude analogously to Theorem 3, along with Remark 2, choosing .

On the other hand, to recover the initial condition, we proceed as in the proof of Theorem 3.

Hence, we are able to recover univocally when knowing in , using its values and the values of its derivatives at some finite set of time instants in ; concretely, between and ddistinct suitable time points. ∎

We present in Algorithm 3 a method to recover and/or knowing only in some , based on the proof of previous Lemma 3. In particular, we will need to find between and different time instants in when some analyticity properties are satisfied.

Algorithm 2. In a way similar to that of Algorithm 3, we describe here a slightly different constructive method to recover and/or assuming that we know (satisfying System (2)) in some and some analyticity hypotheses are fulfilled. Since the procedure is similar to the one in Algorithm 3, we only state here the steps that change:

-

Step 2.

If is unknown, find , for any , positively invariant with respect to the ODE system given in (2) such that , and maps and , for some suitable , , , such that (C1), (C2) and (C3) of Theorem 2 are satisfied, being in (C2) and (C3) a connected set satisfying , and such that functions are analytic in , for any , , .

-

Step 4.

Same as in Algorithm 3 but such that, for each , .

-

Step 7.

Same as in Algorithm 3, but such that .

Notice again that we need to find in the sets of time instants required in Step 4, and hence again may be difficult to find in practice. However, we can reduce this quantity of time instants to time if we use higher derivatives of , as will be shown next.

3.4 Using higher-order derivatives

In this section, we present a methodology which uses higher derivatives of and may be more convenient in some cases. Some classical differential algebra methodologies use higher-order derivatives and, once they obtain the expressions of these derivatives, they study the identifiability of the system from a differential algebra viewpoint (recall, for example, [26, 28, 52]). In the methodology presented in Lemma 4 and Algorithm 4 we still determine the identifiability of System (2) studying the linear independence, which in several cases will be easier than what is performed in the other methodologies. The use we make of higher-order derivatives allows to reduce to one the number of time instants that we need to find in to recover the unknown parameters, once we know the system is identifiable. Therefore, notice that using these higher-order derivatives is an alternative to recover the unknowns using less time instants but is not necessary for proving the identifiability of the system, as it is in the aforementioned works.

Lemma 4.

For each , let be positively invariant with respect to the ODE system in (2). Let . Assume we know in some semi-open interval , and the hypotheses of Theorem 1 and Lemma 2 are satisfied for some such that . If we further assume that , , , for any , being , then System (2) is jointly observable-identifiable and we can reconstruct univocally using the value of and its derivatives at only one time in ; in particular, this time can be almost any .

Proof.

Let us take in , for all . Since

where does not depend on time, we differentiate each of these equations, for , times such that

By the proof of [44, Lemma 3], we know that are linearly independent in , and hence there exists some (see [5]) such that

where is the Wrońskian of , i.e., there exists a unique solution to

Moreover, is also analytic, and therefore it can only vanish at isolated points [58, Theorem 8.5], i.e., the previous equation is fulfilled for almost every . Furthermore, since each , , only vanishes at a countable set of times, then all of them are non-null simultaneously for almost every . Hence, we can choose almost any time such that the previous system has a unique solution considering , for every .

In a way similar to that of the proof of [44, Theorem 3], we may recover our original parameter vector as

Having recovered , we can recover in the same way as exposed in the proof of [44, Lemma 3].

Hence, we are able to recover univocally when knowing , , using its value and the value of its derivatives at one time in , which can be almost any . ∎

Therefore, if we ask for higher regularity of the components of , , than required in [44, Lemma 3], we can recover and choosing only one time in , instead of a number of distinct time instants between and (see Remark 2). We present next the associated algorithm.

Algorithm 3. In a way similar to those of Algorithm 3 and Algorithm 3, we describe here a different constructive method to recover and/or assuming that we know (satisfying System (2)) in some , some analyticity properties are fulfilled and is smooth enough. This method is presented in the proof of Lemma 4, and it requires to choose only one time in . However, it needs the use of higher derivatives of , which are not necessary in the constructive methods explained in Algorithm 3 and Algorithm 3. We only state here the steps that are different from those in Algorithms 3 and 3:

-

Step 2.

Same as in Step 2 of Algorithm 3, along with , for every and each , with .

-

Step 4.

If is unknown, for each , differentiate with respect to time times the equation

where , .

Note: We can differentiate due to the analyticity condition on functions and the regularity conditions on required in Step 2.

-

Step 5.

If is unknown, choose a time such that

(10) where is the Wrońskian of .

Note: This time can be almost any time in due to condition (C3) of Theorem 2, which is verified in Step 2, and the analyticity condition required in Step 2.

-

Step 6.

If is unknown, for each , solve the following linear system which, due to Step 5, has a unique solution :

(11) - Step 7.

-

Step 8.

Same as in Step 7 of Algorithm 3, but now the time we choose can be the same as in Steps 5 and 6 of this algorithm.

-

Step 9.

Same as in Step 8 of Algorithm 3.

Remark 4.

Notice that, as in Remark 2 and Remark 3, we may not need to know in some interval , but only its value and the values of its derivatives (each component up to the th derivative) at one time such that Step 5 in Algorithm 4 is satisfied. Moreover, if and and its derivatives are known at , then we could choose if Step 5 in Algorithm 4 is satisfied and not need to integrate backwards.

Remark 5.

In the algorithms we present here, one can choose a suitable set of time instants , , for Algorithms 3 and 3, and almost any time for Algorithm 4 that fulfill the required properties to reconstruct univocally the parameters and initial condition. Then, one can integrate the system up to the current time to reconstruct the current state. Reconstructing parameters and initial condition or parameters and current state are equivalent as already mentioned, provided the measurements to be error free. However, when facing real data corrupted by some noise, the estimation might depend on the choice of the time instants , for , or the time , and is tainted by some error. Then, integrating the system backwards up to time and forward up to time might propagate and amplify the estimation error on the initial condition and the current state, respectively. A way to improve this estimation is to use a filter in the spirit of an observer (see e.g. [37]). In this work, as the objective is to analyze the identifiability and observability properties, we do not consider here the robustness issue with respect to corrupted data. This will be the matter of a future work.

Up to now, we have provided some hypotheses that ensure a system to be observable, identifiable or jointly observable-identifiable, and some constructive algorithms to recover the initial condition and/or the parameter vector. Besides, if we have some analyticity properties, we can use almost any time to recover these unknowns. Epidemiological models based on autonomous ODEs are typically analytic systems. In particular, if is a combination of linear and bilinear terms of the state variables, then is clearly analytic in all . Due to the Cauchy-Kovalevskaya theorem for ODEs (see [39]), each initial condition provides a unique locally analytic solution. In an autonomous system, any point of a solution can be considered as the initial condition of the same solution, and hence this solution is analytic everywhere. Moreover, in the example presented in Section 2, the output is , which, since is analytic, is also analytic.

Remark 6.

We can apply the proposed algorithms to some systems with piece-wise constant parameters. If the parameter vector is in an interval , , and we know , for all , then we can check the different hypotheses exposed in Algorithms 3, 3 and 4 considering for each that we know in , and apply them respectively if the hypotheses are fulfilled.

Let us now illustrate all the presented theory through the classical SIRS model.

4 Application to the SIRS model

In this section, we study the observability, identifiability and joined observability-identifiability of the SIRS model (1), previously presented in Section 2, under the observation of an unknown fraction of individuals. The associated ODE system is conservative, i.e., ; in particular, is the fraction of susceptible individuals, is the fraction of infectious individuals and is the fraction of recovered individuals, and then , for all (see, for example, [9, Chapter 10.4]). Then, we consider the following reduced system:

| (12) |

for some initial condition . We assume that the four parameters, , , and , and/or the initial condition are unknown.

In this system, (days-1) is the disease contact rate, (days-1) is the transition rate from compartment to compartment , and (days-1) is the transition rate from compartment to compartment . The following results are well-known ([9, Chapter 10.4], [41]):

-

•

The system of ODEs of System (12) with initial condition in has a unique solution.

-

•

The set is positively invariant with respect to the system of ODEs of System (12).

-

•

The basic reproduction number is defined as . It is an approximation of the number of cases that one infected person generates on average over the course of its infectious period, in an uninfected population and without special control measures.

-

•

The (unique) disease-free equilibrium (DFE), which is is globally asymptotically stable when and unstable when ; in particular, in this case, it is a saddle point whose stable manifold is .

-

•

When , there exists an endemic equilibrium (EE) in given by which is globally asymptotically stable out of .

Having done this quick wrap-up on the main characteristics of the SIRS model, we may start to study if it is observable, identifiable or jointly observable-identifiable. Notice that, in particular, the solutions of this system are analytic and, hence, so it is the output.

4.1 Identifiability and observability

Notice that the solutions and observations of System (12) are analytic in . We will see that the procedure described in Algorithm 3 is appropriate for this case, and gives more general results than Algorithm 3. Hence, in the following, we are going to focus on Algorithm 3 considering we know in . In particular, to check the observability, identifiability or joined observability-identifiability of System (12), we are going to follow Steps 1 and 2 and see if the required conditions can be satisfied. First of all, notice that the number of state variables of System (12) is , the number of unknown parameters is and the number of observations is . Let , , . Then, System (12) can be consider as a system of the form given in (2), with

In the following, we will find different suitable sets and , for any , for the above mentioned Steps 1 and 2, respectively. We will do it constructively.

Step 1. In this case, since , we have to find such that, for any , the following function is injective in some suitable set positively invariant w.r.t. the ODE system given in (12):

For any , letting be the solution to System (12) with initial condition and parameter vector , we have

Notice that is injective in a set if, and only if, there exist and some function such that . A set that has this form is positively invariant with respect to the system of ODEs of System (12) if, and only if, for any initial condition , , for all . Two examples of such orbits are and, whenever , .

These type of sets are very restrictive and not very useful in applications. Therefore, let us consider instead of . We will show that this is a more convenient choice since the positively invariant set w.r.t. the ODE system given in (12) that we will derive from it is less restrictive.

Differentiating one time leads to the following equation:

Let us consider .

Lemma 5.

For any , the following map is injective:

| (13) |

Proof.

The proof is straightforward, since, given , ,

Therefore, it is easy to see that (13) is injective. ∎

Notice that, if we change by in Lemma 5, then the mapping is not injective.

To continue with Step 1 of Algorithm 3, we point out that is positively invariant with respect to the system of ODEs of System (12). Notice that is the same set as except for the manifold , which is also positively invariant w.r.t. the ODE system given in (12) (recall that this is the stable manifold associated to when ). Then, due to the uniqueness of solutions, is also positively invariant w.r.t. the ODE system given in (12). Hence, System (12) is observable on in any semi-open interval with parameters in . If we know and some observations , for all , then we can determine performing now Steps 3, 7 and 8 in Algorithm 3.

Step 2. We now need to find a suitable sets , for every , positively invariant w.r.t. the ODE system given in (12), and maps and , for some suitable , , , such that (C1), (C2) and (C3) of Theorem 2 are satisfied for some connected such that and are analytic w.r.t. , for any , , and .

In the following, for the sake of cleanliness, we make a slight abuse of notation and avoid the specification of , and when no confusion is possible; besides, we denote and as and , respectively.

Let us start by checking (C1) of Theorem 2. Since

| (14) |

neither nor are suitable. In particular, we cannot obtain a function injective in suitable for (7) since we do not have any information on in the expressions of and given in (14).

Then, if we continue differentiating , denoting as , we obtain:

| (15) |

Notice that, if , which holds when we consider initial conditions in , we can define in terms of , and from (14) as

| (16) |

Hence, substituting (16) in (15) and performing some computations, we obtain an equation in the form of (7) in (C1) of Theorem 2:

| (17) |

Then, we can see that (C1) of Theorem 2 is satisfied with , , ,

and

Since , we have denoted , , for the sake of simplicity.

Let us now check (C2) of Theorem 2, i.e., if the function is injective. Indeed, given some parameter vector , it is easy to see that we can invert the equation and obtain univocally

Finally, we need to check (C3) of Theorem 2, i.e., if, for any , the functions are linearly independent with respect to time in some suitable , for initial conditions in some suitable sets , for , positively invariant w.r.t. the ODE system given in (12). Since these functions are defined in all , we will consider . Then, if they are linearly independent in , given that they are clearly also analytic, we will have linear independence in any . In the following Lemma 6, we will directly prove linear independence for any .

Lemma 6.

For any , the functions are linearly independent in if and , i.e., , where denotes the endemic equilibrium point associated with .

Proof.

Consider some . For some , we consider , and assume there exist such that

| (18) |

We will prove that if , for some . As mentioned in Step 1, if , then in , and hence (18) is true for values not necessarily satisfying , which implies that the corresponding functions are not linearly independent in .

Therefore, let us consider , i.e., . In this case, if is the solution of the ODE system of (12) with initial condition and parameter vector , recall that is positively invariant w.r.t. the ODE system given in (12), i.e., , for all . Then, we can rewrite (18) as

which leads to

Determining not all of them null such that this is fulfilled is equivalent to determining not all of them null such that

| (19) |

since if, and only if, . That is, we will check whether are linearly independent functions in considering initial conditions in or not.

If we consider that or are constant, (19) is true for values of not necessarily satisfying , which implies that the corresponding functions are not linearly independent in . In , due to the analyticity of the system, this is only possible if . Indeed, implies , which is excluded from , or and hence ; on the other hand, if , then, and

i.e., we are at an equilibrium point.

Hence, let us take and check if, when , the corresponding functions are linearly independent in for times in . Assume that (19) holds and at least one between and is non-null. If we consider initial conditions in , we obtain the following expression for :

where is non-null for almost every , since is analytic and non-constant in . Without loss of generality, assume is non-null for all . We can hence differentiate this expression for and obtain

On the other hand,

If we equal both expressions for , we get

for . After some computations in order to get rid of the denominators, we reach the following polynomial on :

where

Since is analytic non-constant in , for this polynomial to be 0 in , we need that . We have assumed that at least one between and is non-null. We have two subcases:

-

•

Assume . Then, it is straightforward observing that implies . But then, this implies that in , which cannot happen for solutions in . Hence, .

-

•

Assume , and due to the previous argument. Then, implies or . If , from , we obtain , which again cannot happen for solutions in . If we consider , implies , which is not true since and we have assumed .

Hence, we must have . Then, equation (19) is

But is analytic non-constant for solutions in , and hence .

Therefore, for any , or, equivalently, are linearly independent in any semi-open subinterval if we consider in the following set:

∎

To continue with Step 2, we need to check if the set is positively invariant with respect to the system of ODEs of System (12).

Lemma 7.

Let . The set is positively invariant with respect to the system

| (20) |

Proof.

Let be the disease-free equilibrium of System (20) and, given , the endemic equilibrium (which is inside if, and only if, ). Since the solution of this system given an initial condition is unique in , then the set is still positively invariant with respect to System (20).

On the other hand, if an initial condition is such that , then , for all , due to the uniqueness of solutions. Indeed, since , ,

Thus, is also a positively invariant set with respect to System (20). ∎

Hence, Step 2 is finished, which allows us to conclude that System (12) is identifiable on in any semi-open interval with initial conditions consistent with the family . Actually, if we know and some observations , for , then we can determine performing Steps 3–6 in Algorithm 3.

Step 3. Set , . Then, this is a positively invariant set, and we assume .

Notice that, for any , not considering initial points in is not restrictive with respect to the observations we can work with, since would mean there is no disease and therefore no point of study, and constant means the disease is already endemic and it will not vary unless we perturb the system (e.g., with migration or vaccination).

4.2 A limiting case: The SIR model

Another basic compartmental model is the SIR model, where the considered populations are the same as for System (12), but there is no loss of immunity, i.e., . Again, we can consider the observation of an unknown portion of infected individuals and hence obtain the following system:

| (21) |

where we have already simplified the dimension taking into account that the quantity is preserved.

If one thinks of whether System (21) is observable, identifiable or jointly observable-identifiable, it seems it will satisfy the same properties as the previous System (12), and it will be easier to prove them, since we got rid of parameter . However, this is far from being true.

If we perform the same computations as for the SIRS model, we obtain the same result for Step 1, which implies that System (21) is observable on in any with parameters in . Regarding Step 2, as in (16) and (17) with , we obtain that

| (22) |

and

| (23) |

Then,

which is clearly not injective in , and hence we cannot complete Step 2 using (23). However, recalling Remark 1, System (21) is indeed identifiable considering a suitable positively invariant subset of , as we can see in the following Lemma (8), which does not need the injectivity of .

Lemma 8.

System (21) is identifiable on in any , with initial conditions in 222Note that is independent of the choice of ..

Proof.

System (21) will be identifiable on with initial conditions in if, given any initial condition and some observations in , we can determine univocally.

First of all, one can prove, similarly to Lemma 7, that is positively invariant with respect to the ODE system in System (21). Equations (22) and (23) are still valid. Therefore, if we prove that and are linearly independent w.r.t. , then there is a unique solution to

| (24) |

where and . To see that the linear independence holds, let us consider such that

Since is positively invariant, then in , and hence , which implies

This is equivalent to

Since is analytic, or are non-null if, and only if, is constant. Given that , this can only happen if or , for all , which cannot occur in . Hence, and are linearly independent when we consider and , and therefore there is a unique solution to (24). Then, we can determine univocally and .

If , taking into account that in , we can conclude directly determining

If , notice now that we can make the following change of variables in the ODE system in System (21): and . Then,

and we can recover and integrating backwards considering as initial condition

Once we know and , taking into account that in , we can determine univocally , and as

∎

Therefore, System (21) is observable on with parameters in and identifiable on with initial conditions in , in any . Nevertheless, it is not jointly observable-identifiable on . Actually, in [13], the authors treat this case and prove that, assuming both and unknown, we can only determine , , and , i.e., it is partially jointly observable-identifiable. In fact, considering (22) and (23), if is the solution to

(which we know is unique due to the proof of Lemma 8) and is any solution to , notice that our method matches this result, since we have

and hence, if we know and , it is straightforward checking that we can recover , , , univocally as follows:

and we cannot obtain more information. If , then we can proceed as in the proof of Lemma 8 performing the change of variables and and integrating backwards from to .

One could also not know at first if some given observations correspond to an SIR or an SIRS model when both and are unknown, and wonder if the same data might be reproduced with two different sets of parameters and , . To tackle this question, we consider an extended SIRS model with parameters

Notice that the SIR model is a particular case of this extension of the SIRS model, and can be regarded as a limiting case of the SIRS model when .

Then again, in Step 2 we would obtain

which is not injective in and hence we cannot complete this step with this function . Nevertheless, this extended model can help to distinguish whether the observations come from an SIR model or an SIRS model, as illustrated in Section 4.2.2. Let us first do a quick comparison between both models in Section 4.2.1.

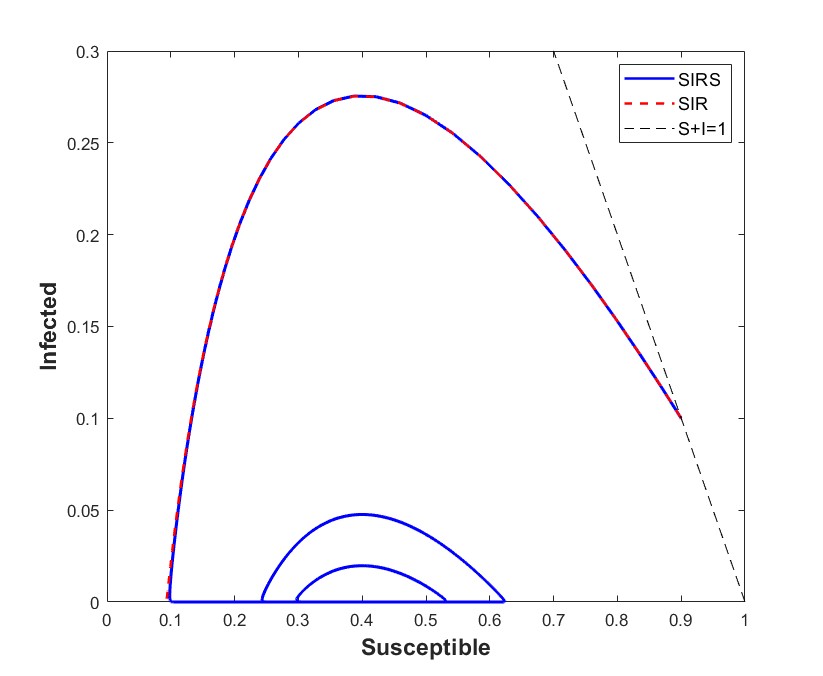

4.2.1 Comparison between SIR and SIRS models

Although passing from to may change substantially the behavior of the solutions, since the SIR model does not admit an endemic state, whereas the SIRS model does, they can be hardly distinguishable at early stages if is very small. We let and be the solutions to the SIR given by the ODE system of (21) and the SIRS model (20), respectively, with the same initial condition, and we study the dependence of on . To do this, we are going to consider the same parameters and for both models, and we will base ourselves on Theorem 3.4., Chapter 3 of [41], particularized to our autonomous context:

Theorem 4.

[41, Chapter 3] Let be a Lipschitz map on with a global Lipschitz constant , where is an open connected set. Let and be solutions of

such that , , for all . Suppose that

for some . Then,

Then, we are going to check the different conditions required in Theorem 4 in order to obtain an estimation of .

Notice that both models share the same positively invariant set

which is compact, but the derivatives are well defined. Let and be the state variables associated to the ODE system of (21) and (20), respectively. We are going to rewrite these systems in the form presented in Theorem 4. Let be the same initial condition at for both models, and two parameter vectors, and the following function:

Notice that is Lipschitz in on the compact set , for some Lipschitz constant which is independent of .

Let us also define

Then, satisfies

We consider now the two following systems:

and

Then, we are under the conditions of Theorem 4. Let us make an abuse of notation and let and . It is fulfilled that

This is, for any , , there exists some small enough such that

| (25) |

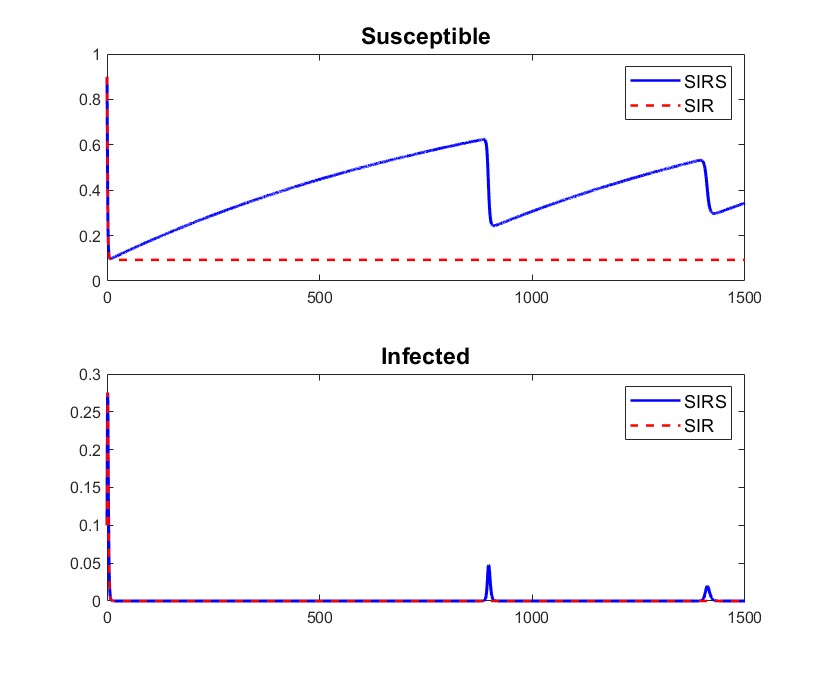

To illustrate this, we can observe in Figure 1 (Left) how both solutions are hardly distinguishable when considering , , and . Moreover, the infectious compartment presents a slow-fast behavior for the SIRS model when near to the invariant manifold ; we observe in Figure 1 (Right, Bottom) how it takes a lot of time to move away from the manifold and then approaches it very fast, and hence remains most of the time very close to the solution of for the SIR model. Hence, it is reasonable that is hardly distinguishable from small values of knowing only the infectious compartment. Moreover, Figure 1 illustrates that this difficulty may not only be at initial times, but also for intermediate intervals of time.

4.2.2 Distinguishing between SIR and SIRS models

Given the previous study, it is intuitive to think that, in a practical viewpoint, it may be difficult distinguishing an SIR model from an SIRS model with very small if we look at short times. However, it is theoretically possible. We present here two approaches to do this.

-

•

Approach 1: One can check analogously to the SIRS case that are linearly independent for the SIR case in any in its positively invariant set . Then, given some observations , we can perform Step 3 of Algorithm 3: we know there exist different time instants , where is the one in (25), such that there exists a unique solution fulfilling

Given , we obtain the following conclusions:

-

–

if , we confirm that our observations correspond to an SIR model;

-

–

if , then we are at an SIRS model;

-

–

if and , we conclude our observations do not match any of the two models.

-

–

-

•

Approach 2: Another way to determine if there is loss of immunity or not consists in considering the previous equality (23), i.e.,

i.e., are linearly dependent for the SIR model whenever . However, this is not true for the SIRS model. Indeed, consider System (12). Let such that

This is equivalent to

which again reduces to study the linear independence of , which we already know that are linearly independent in any in each set , , defined in Section 4.1. Therefore, given , and , studying the linear dependence of may help us determine the model.

5 Some other applications

In this section, we present a series of additional examples to demonstrate the broader applicability of our approach to other epidemiological models. In each example, we illustrate how joined observability-identifiability can be established using our proposed framework, under different modeling assumptions and data limitations. For clarity, we systematically omit the equation of the Recovered compartment in cases where the total population is constant, as it does not affect the theoretical results. To keep the focus on the theoretical aspects, detailed computational steps are omitted but can be derived straightforwardly following the procedures outlined in previous sections.

The SIR model with demography

In [18], the authors show that the following model is neither identifiable nor observable:

where denotes the birth and death rates, assumed equal, is the total population (constant), and , , and represent the same parameters as in the previous models.

However, this model becomes jointly observable-identifiable when the total population is known, allowing us to normalize the population so that and now represent fractions of the total population:

| (26) |

for some initial condition .

For this normalized system, we set and for . Performing computations analogous to those in Section 4.1 during Step 1 and Step 2, we obtain the following relations:

assuming , and

Then, we consider , , , ,

and

With these expressions, we confirm that the assumptions in Step 1 and Step 2 of Algorithm 3 are satisfied, taking parameters in and initial conditions consistent with the family , with , for each , where denotes the equilibrium point associated with , and is positively invariant with respect to the ODE system of (26) when we consider as parameter vector.

Therefore, we conclude that System (26) is jointly observable-identifiable on in any .

The SIRV model

We now analyze a Susceptible-Infectious-Recovered-Vaccinated (SIRV) model, where individuals gain permanent immunity after recovery, as in the SIR model. Additionally, we assume the existence of a perfect vaccine that provides permanent immunity but is only effective for susceptible individuals. Importantly, this vaccine has no effect on infectious or recovered individuals. However, since we cannot distinguish susceptible individuals from infectious or recovered ones, all compartments are vaccinated indiscriminately. The observable data are the rate of vaccinated individuals (including both effective and ineffective vaccinations). Hence, we consider the following system, where , , and are fractions of the total population, assumed to be known:

| (27) |

for some initial condition . We assume that the initial condition and all parameters , , and are unknown, where and are as defined in previous models, and (days-1) represents the vaccination rate.

For this system, we define and for . After some computations, we obtain the following relations:

assuming , and

Then, we consider , , , ,

and

Following the procedures established in earlier sections, we confirm that the assumptions of Step 1 and Step 2 in Algorithm 3 are met, with parameters in and initial conditions in the revised set , where does not depend on and is positively invariant under the ODE system defined by (27).

Thus, we conclude that System (27) is jointly observable-identifiable on in any .

The SIR model (with a different output)

As discussed in Section 4.2, the SIR model observed through a fraction of infected individuals (i.e., System (21)) is observable and identifiable, but not jointly observable-identifiable. Here, we consider the same SIR model but with a different observation: the instantaneous incidence rate. Specifically, we examine the following system:

| (28) |

for some initial condition , which is positively invariant with respect to the system of ODEs given in (28). In this scenario, we assume that both and are unknown parameters, defining for . Following an approach similar to previous cases, we calculate the first derivative of to express and in terms of and :

Notice that this system is nonlinear in and , making it challenging to directly apply Step 1 of Algorithm 3. To address this, let us differentiate once more:

which results in a system that is linear in and . Therefore, we obtain:

Assuming , we avoid further differentiation by substituting the expressions of and into , yielding the following equation after simplification:

Then, we set , , ,

and

We confirm that the assumptions of Step 1 and Step 2 in Algorithm 3 hold, with parameters in and initial conditions in , where does not depend on and is positively invariant with respect to the system of ODEs of System (28).

Consequently, we conclude that System (28) is jointly observable-identifiable on in any .

The SIV model with demography and two outputs

Here, we consider a Susceptible-Infectious-Vaccinated (SIV) model with demographic dynamics. We assume a perfect vaccine that is effective only for susceptible individuals, though infectious individuals are also vaccinated indiscriminately, as in System (27). In this case, however, we model a permanent infection, which can serve as a simplified representation of long-term infections, such as those associated with certain sexually transmitted diseases (e.g., human papillomavirus (HPV)). We assume two observable quantities: the rate of all vaccinated individuals (both effective and ineffective) and the rate of natural deaths. These deaths are attributed to natural population dynamics and are assumed to be routinely monitored by authorities. Hence, we consider the following system, where , , and represent the fraction of susceptible, infectious, and vaccinated individuals, respectively:

| (29) |

for some initial condition . All the initial condition and the parameters , , , and are assumed to be unknown. Here, represents a constant recruitment rate, is the death rate, and and have the same definitions as in System (27).

The natural positively invariant set for this system is , and , for .

We first observe that this system is not observable (and hence not jointly observable-identifiable) if only is used as the observation, similar to System (27). Since depends solely on and , we cannot uniquely determine . Therefore, an additional observation is required. By including the rate of natural deaths, , we leverage data that should be routinely available, making it reasonable to assume accessibility to this information.

Similarly, relying on alone is insufficient, as yields no further parameter information through differentiation, unlike previous models.

After some computations, differentiating twice and once, we obtain the following expressions:

and

Focusing on the equation , we observe that , when is non-constant, allows us to determine and by solving the system:

such that and . Substituting, we can rewrite:

This reformulation ensures the linear independence condition in Step 2 of Algorithm 3. Then, we consider , , , , , , ,

and

Given this, the assumptions in Step 1 and Step 2 of Algorithm 3 hold for parameters in and initial conditions consistent with the family , such that, for , , where is the equilibrium point of the system and is positively invariant under the ODEs of System (29) when considering as the parameter vector.

Therefore, we conclude that System (29) is jointly observable-identifiable on in any .

6 Numerical illustration

In this section, we present numerical experiments designed to illustrate the application of the theoretical framework developed in Sections 3 and 4 for observability, identifiability and joined observability-identifiability in epidemiological models. This numerical analysis also aims to implement the theoretical methods in some cases and demonstrate their practical feasibility under varying conditions. Specifically, we analyze two examples: one based on an SIRS model and another on an SIR model, each chosen to exhibit distinct epidemiological dynamics:

-

•

Case 1: We consider an SIRS model in which the endemic equilibrium is globally asymptotically stable (except for the invariant manifold , as it is stable for the disease-free equilibrium). The solution oscillates when converging to the endemic equilibrium, as in the example presented in Figure 1. We set the following parameters and initial conditions: and . Thus, the basic reproduction number is .

-

•

Case 2: We consider an SIR model that exhibits an epidemic peak. The chosen parameters and initial conditions are and . Here as well, .

To simulate these cases, we approximate each solution using a fourth-order Runge-Kutta algorithm and synthetically generate observations, , at each time-step. In this initial study, we assume noise-free data to establish a clear baseline for comparison. We then analyze two scenarios:

-

•

Scenario 1: We assume that continuous observations of are available over the interval , with exact knowledge or computability of its derivatives (enabled by the analyticity of the system). We apply the recovery procedure outlined in Algorithm 4 to determine the original parameters and initial condition, utilizing the full interval .

-

•

Scenario 2: In realistic situations, data are typically discrete, often recorded at daily intervals by public health authorities (e.g., [68] and [69]). To mimic this, we extract simulated data once per day (at the same time each day), referred to here as daily data, and apply the Ordinary Least Squares method to estimate the unknown parameters.

Scenario 1 provides a controlled environment for testing recovery procedures and Scenario 2 reflects more realistic, discrete data conditions. For practical purposes, we will examine Case 1 under Scenario 1 and Case 2 under Scenario 2. Preliminary results indicated similar outcomes when interchanging cases between scenarios, allowing us to streamline the analysis. In Scenario 1, we focus on the procedure in Algorithm 4, omitting that of Algorithm 3 due to the former’s superior performance.

To integrate numerically the ODE systems, we utilize a fourth-order Runge-Kutta method with a time-step of days, extending up to a maximum simulation time of days. Although the maximum time may seem low, it was sufficient to capture the dynamics required for convergence in Scenario 2. Furthermore, we employ the extended SIRS model from Section 4.2, assuming no prior knowledge regarding whether or .

6.1 Scenario 1: Linear systems for continuous observations

In this section, we perform numerical tests for Case 1, assuming continuous observation of over , i.e., we observe at every time point within this interval, and assume that we know or can compute its exact successive derivatives.

To implement the numerical tests, we first need to construct the necessary data. From an implementation perspective, we obtain the values of and its derivatives at each time-step of the numerical scheme, specifically at each point in the time vector , where and . The data generation steps are as follows:

-

1.

We approximate the solutions and of the SIR or SIRS system with a small time-step using the fourth-order Runge-Kutta scheme, and define our observations as .

-

2.

We approximate the first derivative of by .

-

3.

For higher-order derivatives, we use the following linear equation in terms of parameters , :

where , , , and . Using this relationship, we iteratively approximate higher-order derivatives of through lower-order derivatives.

With these generated data, we apply the method in Algorithm 4 to estimate the system parameters and initial condition. This method requires selecting a time such that the following system has a unique solution (see (10)-(11)):

| (30) |

Instead of directly estimating , we focus on estimating

The initial conditions and are then computed as

Knowing the observation at time 0 avoids the computational challenges of backward integration.

Assuming known values of and , we aim to calibrate

To evaluate the method’s performance, we conducted 161 experiments, corresponding to . For each time point in , we examined:

-

•

The relative error between each computed component of and its exact value. These errors were consistently small, with a maximum of the order of , confirming the high accuracy of the method.

-

•

The determinant of the matrix in (30), which should be non-zero. The values obtained were of the order of .

-

•

The condition number of the matrix in (30) (based on the -norm). All the obtained values range between and .

-

•

The computational time (in seconds). Performing all tests took approximately seconds.

These results indicate that the method provides accurate parameter estimates despite the small determinant values and the matrix conditioning. The computational efficiency demonstrated, completing 161 tests in minimal time, makes this approach highly suitable for real-time applications.

Similar results were observed for Case 2, which are omitted here for brevity.

6.2 Scenario 2: OLS method for daily observations

In this section, we analyze Case 2 under the assumption of daily, noise-free observations from the deterministic model. Daily observations reflect realistic data collection practices in epidemiology, such as those by public health authorities. Given the discrete nature of the data, calculating derivatives directly can result in inaccuracy (if differentiated numerically) or bias (if interpolated prior to differentiation). In this context, we employ the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method to estimate the values of , , , , and . Let represent the parameter vector, where we calibrate 4 parameters (, , , and ) and 1 initial condition (). The goal is to find by solving

where is the solution to the following system of ODEs:

with . Here, we define a new feasible set . To enhance sensitivity to small deviations, a scaling factor is introduced in the objective function.

The choice of days (using daily data) was based on preliminary testing, where this time-frame was found sufficient for reliable parameter estimation despite its brevity.

For this experiment, we use the MATLAB function lsqcurvefit to solve the OLS problem, adjusting settings for increased accuracy (see [50]). Specifically, we set the maximum evaluations to , iterations to , step tolerance to , and function tolerance to .

We impose the following bounds for the parameters, with subscripts and indicating the minimum and maximum values, respectively: , , , , and . The bounds for are informed by studies on estimates for diseases such as smallpox, pertussis, or COVID-19 (e.g., [23], [43], [45], [46], [66], [67]).

We initialize the OLS algorithm several times with random initial conditions, denoted as I.C., drawn from a uniform distribution . Each initial condition is generated as:

where . For conciseness, we report results from 5 representative tests. Table 2 includes the following outcomes: Test (test number), I.C. (initial condition for lsqcurvefit), Abs. error (absolute error between the computed solution and the true parameter vector ), Obj. value (final objective function value), and Time (s) (computational time for each test in seconds).

| Test | I.C. | Abs. error | Obj. value | Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (0.545 1.967 0.414 0.82 0.718) | (0.019 0.015 6.8e-6 4.7e-6 0.052) | 6.324e-12 | 116.517 |

| 2 | (0.97 1.599 0.332 0.106 0.611) | (0.226 0.189 8.9e-12 9.3e-13 0.387) | 7.657e-19 | 1.904 |

| 3 | (0.785 1.276 0.1 0.266 0.154) | (0.25 0.208 4e-11 3.6e-12 0.409) | 9.036e-18 | 1.546 |

| 4 | (0.686 0.874 0.675 0.695 0.068) | (0.7 0.286 0.270 0.096 0.024) | 0.003 | 621.808 |

| 5 | (0.277 0.68 0.671 0.844 0.344) | (0.7 0.287 0.271 0.097 0.024) | 0.006 | 1380.792 |

| Test | Approx. of | Approx. of |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (0.319 0.265 0.1 4.7e-6 0.848) | (0.1 0.833 0.225) |

| 2 | (0.526 0.439 0.1 9.3e-13 0.513) | (0.1 0.833 0.225) |

| 3 | (0.55 0.458 0.1 3.6e-12 0.491) | (0.1 0.833 0.225) |

| 4 | (1 0.536 0.370 0.096 0.924) | (0.370 0.536 0.495) |

| 5 | (1 0.537 0.371 0.097 0.924) | (0.371 0.537 0.496) |

The target parameter vector is

but as noted in Section 4.2, we can only determine specific combinations: , , , . Defining ,

Table 2 compares approximations for and , showing accurate convergence for and in Tests 1, 2 and 3. Despite inaccuracies in , , and in these tests, the objective function values are low, indicating that the algorithm converged successfully for the key identifiable combinations. Most of the tests not presented here converged similarly.

In Tests 4 and 5, the parameters reach a similar solution, representing an SIRS model with