Incorporating Both Distributional and Relational Semantics in Word Representations

Abstract

We investigate the hypothesis that word representations ought to incorporate both distributional and relational semantics. To this end, we employ the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM), which flexibly optimizes a distributional objective on raw text and a relational objective on WordNet. Preliminary results on knowledge base completion, analogy tests, and parsing show that word representations trained on both objectives can give improvements in some cases.

1 Introduction

We are interested in algorithms for learning vector representations of words. Recent work has shown that such representations can capture the semantic and syntactic regularities of words Mikolov et al. (2013a) and improve the performance of various Natural Language Processing systems Turian et al. (2010); Wang & Manning (2013); Socher et al. (2013a); Collobert et al. (2011).

Although many kinds of representation learning algorithms have been proposed so far, they are all essentially based on the same premise of distributional semantics Harris (1954). For example, the models of Bengio et al. (2003); Schwenk (2007); Collobert et al. (2011); Mikolov et al. (2013b); Mnih & Kavukcuoglu (2013) train word representations using the context window around the word. Intuitively, these algorithms learn to map words with similar context to nearby points in vector space.

However, distributional semantics is by no means the only theory of word meaning. Relational semantics, exemplified by WordNet Miller (1995), defines a graph of relations such as synonymy and hypernymy Cruse (1986) between words, reflecting our world knowledge and psychological predispositions. For example, a relation like “dog is-a mammal” describes a precise hierarchy that complements the distributional similarities observable from corpora.

We believe both distributional and relational semantics are valuable for word representations, and investigate combining these approaches into a unified representation learning algorithm based on the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM) Boyd et al. (2011). Its advantages include (a) flexibility in incorporating arbitrary objectives, and (b) relative ease of implementation. We show that ADMM effectively optimizes the joint objective and present preliminary results on several tasks.

2 Distributional and Relational Objectives

Distributional Semantics Objective: We implement distributional semantics using the Neural Language Model (NLM) of Collobert et al. (2011). Each word in the vocabulary is associated with a -dimensional vector , the word’s embedding. An -length sequence of words is represented as a vector by concatenating the vector embeddings for each word, . This vector is then scored by feeding it through a two-layer neural network with hidden nodes: , where , , are network parameters and is the sigmoid applied element-wise. The model is trained using noise contrastive estimation (NCE) Mnih & Kavukcuoglu (2013), where training text is corrupted by random replacement of random words to provide an implicit negative training example, . The hinge-loss function, comparing positive and negative training example scores, is:

| (1) |

The word embeddings, , and other network parameters are optimized with backpropagation using stochastic gradient descent (SGD) over n-grams in the training corpus.

Relational Semantics Objective: We investigate three different objectives, each modeling relations from WordNet. The Graph Distance loss, , enforces the idea that words close together in the WordNet graph should have similar embeddings in vector space. First, for a word pair , we define a pairwise word similarity as the normalized shortest path between the words’ synonym sets in the WordNet relational graph Leacock & Chodorow (1998). Then, we encourage the cosine similarity between their embeddings and to match that of :

| (2) |

where and are parameters that scale to be of the same range as the cosine similarity. Training proceeds by SGD: word pairs are sampled from the WordNet graph, and both the word embeddings and parameters , are updated by gradient descent on the loss function.

A different approach directly models each WordNet relation as an operation in vector space. These models assign scalar plausibility scores to input tuples , modeling the plausibility of a relation of type between words and . In both of the relational models we consider, each type of relationship (for example, synonymy or hypernymy) has a distinct set of parameters used to represent the relationship as a function in vector space. The TransE model of Bordes et al. (2013) represents relations as linear translations: if the relationship holds for two words and , then their embeddings should be close after translating by a relation vector :

| (3) |

Socher et al. (2013b) introduce a Neural Tensor Network (NTN) that models interaction between embeddings using tensors and a non-linearity function. The scoring function for a input tuple is:

| (4) |

where , , and are parameters for relationship . As in the NLM, parameters for these relational models are trained using NCE (producing a noisy example for each training example by randomly replacing one of the tuples’ entries) and SGD, using the hinge loss as defined in Eq. 1, with replaced by the or scoring function.

Joint Objective Optimization by ADMM: We now describe an ADMM formulation for joint optimization of the above objectives. Let be the set of word embeddings for the distributional objective, and be the set of word embeddings for the relational objective, where and are the vocabulary size of the corpus and WordNet, respectively. Let be the set of words that occur in both. Then we define a set of vectors = , which correspond to Lagrange multipliers, to penalize the difference between sets of embeddings for each word in the joint vocabulary , producing a Lagrangian penalty term:

| (5) |

In the first term, has same dimensionality as and , so a scalar penalty is maintained for each entry in every embedding vector. This constrains corresponding and vectors to be close to each other. The second residual penalty term with hyperparameter is added to avoid saddle points; can be viewed as a step-size during the update of .

This augmented Lagrangian term (Eq. 5) is added to the sum of the loss terms for each objective (Eq. 1 and Eq. 2). Let be the parameters of the distributional objective, and be the parameters of the relational objective. The final loss function we optimize becomes:

| (6) |

The ADMM algorithm proceeds by repeating the following three steps until convergence:

(1) Perform SGD on and to minimize , with all other parameters fixed.

(2) Perform SGD on and to minimize , with all other parameters fixed.

(3) For all embeddings corresponding to words in both the n-gram and relational training sets, update the constraint vector .

Since and share no parameters, Steps (1) and (2) can be optimized easily using the single-objective NCE and SGD procedures, with additional regularization term .

3 Preliminary Experiments & Discussions

| NLM | GD | GD+NLM | TransE | TransE+NLM | NTN | NTN+NLM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Base | - | - | - | 82.87 | 83.10 | 80.95 | 81.27 |

| Analogy Test | 42 | 41 | 41 | 37 | 38 | 36 | 41 |

| Parsing | 76.03 | 75.90 | 76.18 | 75.86 | 76.01 | 75.85 | 76.14 |

The distributional objective is trained using 5-grams from the Google Books English corpus111Berkeley distribution: tomato.banatao.berkeley.edu:8080/berkeleylm_binaries/, containing over 180 million 5-gram types. The top 50k unigrams by frequency are used as the vocabulary, and each training iteration samples 100k n-grams from the corpus. For training , we sample 100k words from WordNet and compute the similarity of each to 5 other words in each ADMM iteration. For training and , we use the dataset of Socher et al. (2013b), presenting the entire training set of correct and noise-contrastive corrupted examples one instance at a time in randomized order for each iteration.

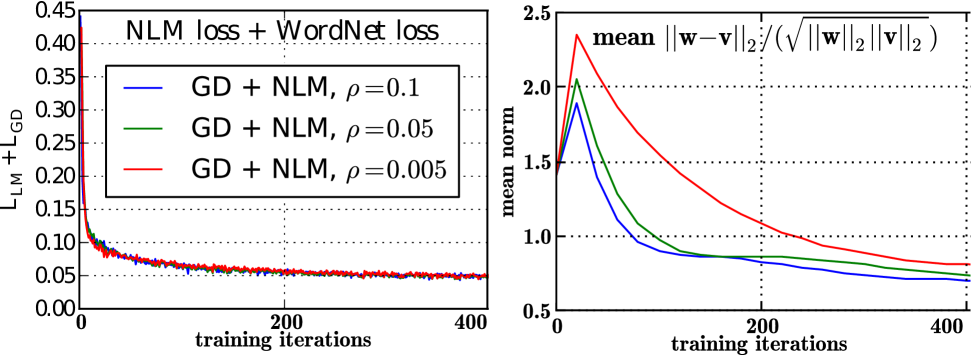

We first provide an analysis of the behavior of ADMM on the training set, to confirm that it effectively optimizes the joint objective. Fig. 1(left) plots the learning curve by training iteration for various values of the hyperparameter. We see that ADMM attains a reasonable objective value relatively quickly in 100 iterations. Fig. 1(right) shows the averaged difference between the resulting sets of embeddings and , which decreases as desired.222The reason for the peak around iteration 50 in Fig. 1 is that the embeddings begin with similar random initializations, so initially differences are small; as ADMM starts to see more data, and diverge, but converge eventually as become large.

Next, we compare the embeddings learned with different objectives on three standard benchmark tasks (Table 1). First, the Knowledge Base Completion task Socher et al. (2013b) evaluates the models’ ability to classify relationship triples from WordNet as correct. Triples are scored using the relational scoring functions (Eq.3 and 4) with the learned model parameters. The model uses a development set of data to determine a plausibility threeshold, and classifies triples with a higher score than the threshold as correct, and those with lower score as incorrect. Secondly, the SemEval2012 Analogy Test is a relational word similarity task similar to SAT-style analogy questions Jurgens et al. (2012). Given a set of four or five word pairs, the model selects the pairs that most and least represent a particular relation (defined by a set of example word pairs) by comparing the cosine similarity of the vector difference between words in each pair. Finally, the Dependency Parsing task on the SANCL2012 data Petrov & McDonald (2012) evaluates the accuracy of parsers trained on news domain adapted for web domain. We incorporate the embeddings as additional features in a standard maximum spanning tree dependency parser to see whether embeddings improve generalization of out-of-domain words. The evaluation metric is the labeled attachment score, the accuracy of predicting both correct syntactic attachment and relation label for each word.

For both Knowledge Base and Parsing tasks, we observe that joint objective generally improves over single objectives: e.g. TransE+NLM (83.10%) TransE (82.87%) for Knowledge Base, GD+NLM (76.18%) GD (75.90%) for Parsing. The improvements are not large, but relatively consistent. For the Analogy Test, joint objectives did not improve over the single objective NLM baseline. We provide further analysis as well as extended descriptions of methods and experiments in a longer version of the paper here: http://arxiv.org/abs/1412.4369.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by a Microsoft Research CORE Grant and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 26730121. D.F. was supported by the Flinn Scholarship during the course of this work. We thank Haixun Wang, Jun’ichi Tsujii, Tim Baldwin, Yuji Matsumoto, and several anonymous reviewers for helpful discussions at various stages of the project.

References

- Bengio et al. (2003) Bengio, Yoshua, Ducharme, Réjean, Vincent, Pascal, and Jauvin, Christian. A neural probabilistic language models. JMLR, 2003.

- Bordes et al. (2013) Bordes, Antoine, Usunier, Nicolas, Garcia-Duran, Alberto, Weston, Jason, and Yakhnenko, Oksana. Translating embeddings for modeling multi-relational data. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pp. 2787–2795, 2013.

- Boyd et al. (2011) Boyd, Stephen, Parikh, Neal, Chu, Eric, Peleato, Borja, and Eckstein, Jonathan. Distributed optimization and statistical learning via the alternating direction method of multipliers. Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning, 3(1):1–122, 2011.

- Collobert et al. (2011) Collobert, R., Weston, J., Bottou, L., Karlen, M., Kavukcuoglu, K., and Kuksa, P. Natural language processing (almost) from scratch. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 12:2493–2537, 2011.

- Cruse (1986) Cruse, Alan D. Lexical Semantics. Cambridge Univ. Press, 1986.

- Harris (1954) Harris, Zellig. Distributional structure. Word, 10(23):146–162, 1954.

- Jurgens et al. (2012) Jurgens, David A, Turney, Peter D, Mohammad, Saif M, and Holyoak, Keith J. Semeval-2012 task 2: Measuring degrees of relational similarity. In Proceedings of the First Joint Conference on Lexical and Computational Semantics, pp. 356–364. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2012.

- Leacock & Chodorow (1998) Leacock, Claudia and Chodorow, Martin. Combining local context and WordNet similarity for word sense identification. WordNet: An Electronic Lexical Database, pp. 265–283, 1998.

- Mikolov et al. (2013a) Mikolov, Tomas, Yih, Wen-tau, and Zweig, Geoffrey. Linguistic regularities in continuous space word representations. In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, pp. 746–751, Atlanta, Georgia, June 2013a. Association for Computational Linguistics. URL http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/N13-1090.

- Mikolov et al. (2013b) Mikolov, Tomás̆, Sutskever, Ilya, Chen, Kai, Corrado, Greg, and Dean, Jeffrey. Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. In NIPS, 2013b.

- Miller (1995) Miller, George A. WordNet: A lexical database for English. Communications of the ACM, 38(11):39–41, 1995.

- Mnih & Kavukcuoglu (2013) Mnih, Andriy and Kavukcuoglu, Koray. Learning word embeddings efficiently with noise-contrastive estimation. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 26 (NIPS 2013), 2013.

- Petrov & McDonald (2012) Petrov, Slav and McDonald, Ryan. Overview of the 2012 shared task on parsing the web. In Notes of the First Workshop on Syntactic Analysis of Non-Canonical Language (SANCL), 2012.

- Schwenk (2007) Schwenk, Holger. Continuous space language models. Computer Speech and Language, 21(3):492–518, July 2007. ISSN 0885-2308. doi: 10.1016/j.csl.2006.09.003. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.csl.2006.09.003.

- Socher et al. (2013a) Socher, Richard, Bauer, John, Manning, Christopher D., and Ng, Andrew Y. Parsing with compositional vector grammars. In Proceedings of the 51st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pp. 455–465, Sofia, Bulgaria, August 2013a. Association for Computational Linguistics. URL http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/P13-1045.

- Socher et al. (2013b) Socher, Richard, Chen, Danqi, Manning, Christopher D., and Ng, Andrew Y. Reasoning with neural tensor networks for knowledge base completion. In NIPS, 2013b.

- Turian et al. (2010) Turian, Joseph, Ratinov, Lev-Arie, and Bengio, Yoshua. Word representations: A simple and general method for semi-supervise learning. In Proceedings of the 48th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 384–394, Uppsala, Sweden, July 2010. Association for Computational Linguistics. URL http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/P10-1040.

- Wang & Manning (2013) Wang, Mengqiu and Manning, Christopher D. Effect of non-linear deep architecture in sequence labeling. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, pp. 1285–1291, Nagoya, Japan, October 2013. Asian Federation of Natural Language Processing. URL http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/I13-1183.