PHENIX Collaboration

Low- direct-photon production in AuAu collisions at and 62.4 GeV

Abstract

The measurement of direct photons from AuAu collisions at and 62.4 GeV in the transverse-momentum range Gev/ is presented by the PHENIX collaboration at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider. A significant direct-photon yield is observed in both collision systems. A universal scaling is observed when the direct-photon spectra for different center-of-mass energies and for different centrality selections at GeV is scaled with for . This scaling also holds true for direct-photon spectra from AuAu collisions at GeV measured earlier by PHENIX, as well as the spectra from PbPb at GeV published by ALICE. The scaling power seems to be independent of , center of mass energy, and collision centrality. The spectra from different collision energies have a similar shape up to of 2 GeV/. The spectra have a local inverse slope increasing with of GeV/ in the range GeV/ and increasing to GeV/ for GeV/. The observed similarity of low- direct-photon production from to 2760 GeV suggests a common source of direct photons for the different collision energies and event centrality selections, and suggests a comparable space-time evolution of direct-photon emission.

I Introduction

The measurement of direct-photon emission plays an important role in the study of collisions of heavy ions [1, 2, 3, 4]. Due to their very small interaction cross section with the strongly interacting matter, photons are likely to escape the collision region with almost no final-state interactions. Thus, they carry information about the properties and dynamics of the environment in which they are produced, such as the energy density, temperature, and collective motion, integrated over space and time.

Direct photons with transverse momenta () of up to a few GeV/ are expected to be dominantly of thermal origin, radiated from a thermalized hot “fireball” of quark-gluon plasma (QGP), throughout its expansion and transition to a gas of hadrons, until the hadrons cease to interact. In addition to the fireball, hard-scattering processes in the initial phase of the collision also emit photons. These prompt photons typically have larger and dominate the direct-photon production at above several GeV/. Experimentally, direct photons are measured together with a much larger number of photons resulting from decays of unstable hadrons, such as and decays. The contribution of these decay photons to the total number of photons needs to be removed with an accuracy of a few percent, which is the main experimental challenge.

The production of thermal photons has been extensively studied through a variety of models with different production processes and mechanisms, different photon rates, as well as a range of assumptions about the initial state of the matter and its space-time evolution. Some of the well-known examples include models developed with an “elliptic-fireball” expansion approach [5, 6], hydrodynamic simulations of the “fireball” evolution [7, 8, 9, 10], the parton-hadron-string dynamics transport approach [11, 12, 13], the thermalizing Glasma [14, 15, 16, 17] and the thermalizing Glasma plus bottom-up thermalization scenarios for calculations of the pre-equilibrium and equilibrium phases [18, 19], reduced radiation from the QGP until the transition temperature is reached [20, 21], as well as calculations in the late hadron-gas phase using the spectral-function approach [21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26]. The strong magnetic fields emerging in heavy ion collisions have been considered as an additional, significant source of photons [27, 28, 29, 30].

The PHENIX experiment at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) was the first to detect a large yield of direct photons in heavy ion collisions at = 200 GeV [31]. Earlier evidence was presented by WA98 [32, 33] for = 17.3 GeV, with mostly upper limits below 1.5 GeV/ in , except for two points obtained from interferometry in the 0.1–0.3 GeV/ range, which is below our threshold. Multiple subsequent publications from PHENIX established that at RHIC energies the direct-photon yield below transverse momenta of 2 GeV/ exceeded what was expected from hard processes by a factor of 10 [34], showed a stronger-than-linear increase with the collision volume [35], and a large anisotropy with respect to the reaction plane [36, 37]. The STAR collaboration also reported an enhanced yield of direct photons at low in AuAu collisions at = 200 GeV [38]; for minimum bias (MB) events the yield measured by STAR is a factor of 3 lower for below 2 GeV/, while it is consistent at higher 111The persisting discrepancy between STAR and PHENIX measurements at low is noted, but can not be resolved by PHENIX alone and thus is not further discussed in this paper.. Observations consistent with the PHENIX AuAu measurements at = 200 GeV were made by the ALICE Collaboration at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) [39] in PbPb collisions at = 2.76 TeV and, more recently, by PHENIX at the lower energies of 39 and 62.4 GeV [40]. The low transverse-momentum yield, for below 2 GeV/, shows a power-law dependence on with a power [40]. The power is independent of centrality or collision energy222Throughout the rest of the paper the subscript will be dropped and will always imply density at midrapidity.. These experimental findings are qualitatively consistent with thermal radiation being emitted from a rapidly expanding and cooling fireball. However, it is challenging for theoretical models to describe all data quantitatively.

To further constrain the sources of low-momentum direct photons, PHENIX continues its program on such measurements in large- and small-system collisions. This paper extends a previous publication on AuAu collisions at and 62.4 GeV [40] and provides more detail about the measurement and the universal features exhibited by direct photons emitted from heavy ion collisions from RHIC to LHC energies, including inverse slopes and the scaling with , both as a function of .

II Low-momentum direct-photon production at = 39 and 62.4 GeV

II.1 Experimental method for measuring direct photons

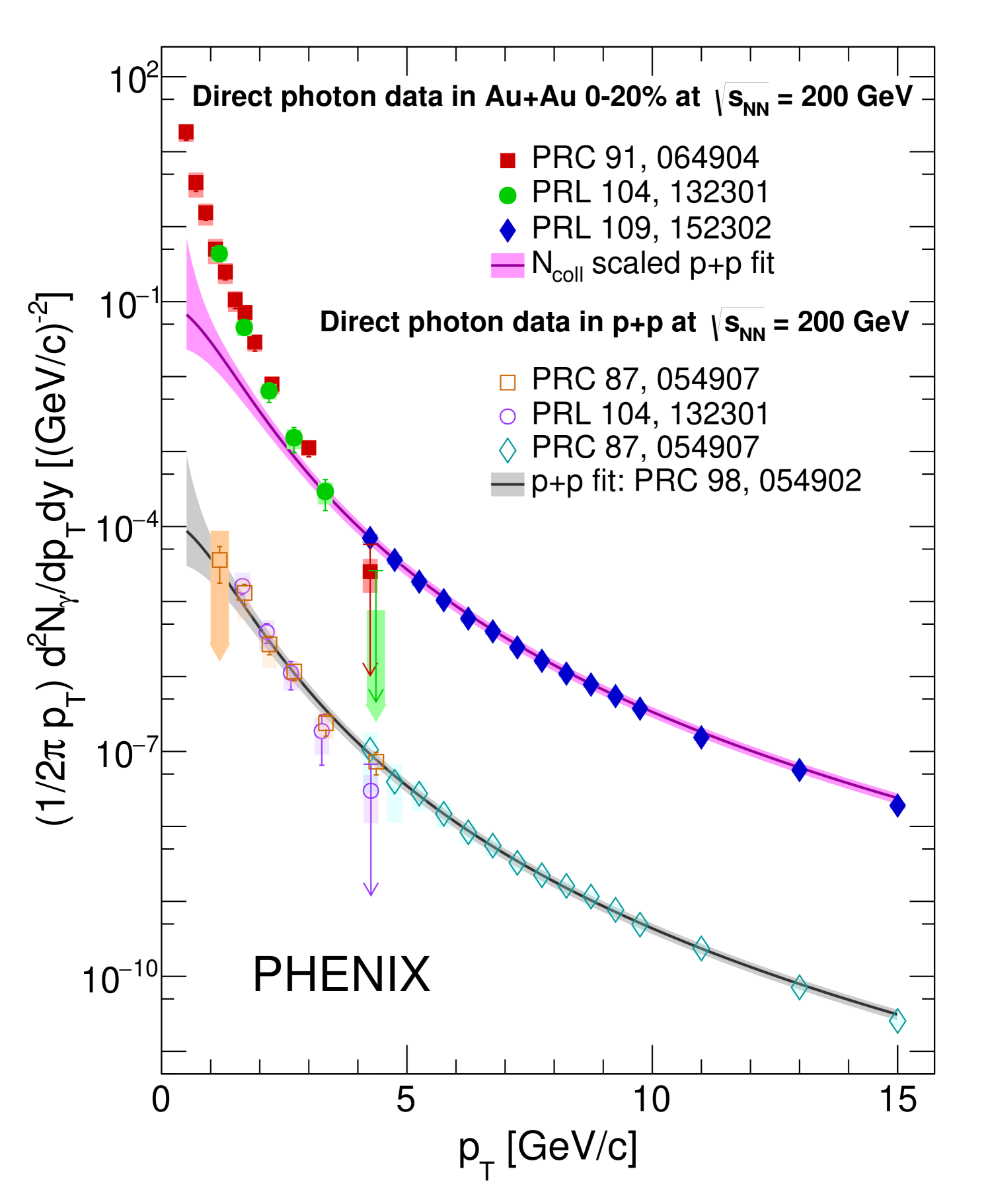

Figure 1 presents the direct-photon spectra measured by PHENIX in AuAu collisions in the 0%–20% centrality bin at = 200 GeV, including data points from an analysis based on external conversions [35], internal conversions [34], and from calorimeter measurements [41]. Also shown are invariant yields of direct photons in collisions at 200 GeV from internal conversions [42, 34], calorimeter measurements [43, 44], a fit to the combined set of data, extrapolated below 1 GeV/ [40, 45, 46, 47], and an -scaled fit with [35].

The three techniques used for measuring direct photons deploy different detector systems within the PHENIX central arms333The PHENIX central arm acceptance is 0.7 units around midrapidity. Thus there is little difference between momentum and transverse momentum, so the terms will be used interchangeably in the following discussion. (see Ref. [48]) and various strategies to extract the direct photons from the decay-photon background include measuring:

-

(i)

photons that directly deposit energy into electromagnetic calorimeters. This is the method of choice to measure high momentum photons. At below a few GeV/, the method suffers from significant background contamination from hadrons depositing energy in the calorimeter and the limited energy resolution [41].

-

(ii)

virtual photons that internally convert into pairs and extrapolating their measured yield to zero mass. This technique was used for the original discovery of low-momentum direct photons at RHIC [34]. The pairs are measured in the mass region above the mass, which eliminates more than 90% of the hadron-decay-photon background. The extrapolation to zero mass requires the pair mass to be much smaller than the pair momentum, and thus limits the measurement to GeV/.

-

(iii)

photons that convert to pairs in the detector material (”external conversion method”). This method gives access to a nearly background-free sample of photons down to below 1 GeV/ [35].

The external-conversion method is used for the analysis presented here, which is the identical method used to analyze direct-photon production from 2010 AuAu collisions at = 200 GeV [35, 37]. Additional details can be found in Ref. [49]. The analysis proceeds in multiple steps. First established is , which is a sample of conversion photons measured in the PHENIX-detector acceptance. This is done in bins of conversion photon . For a given selection, the sample relates to the true number of photons in that range as follows:

| (1) |

where is the pair acceptance, is the pair reconstruction efficiency, and is the conversion probability. In the next step a subsample of is tagged as decay photons; details of how the subsample is determined are described in Sec. II.3 below. Because is a subset of , it is related to the true number of decay photons among by:

| (2) |

with being the average conditional probability of detecting the second photon in the PHENIX acceptance, given that one decay photon converted and was reconstructed in the desired conversion photon range. Here the average is taken over all possible . Taking the ratio of Eq. 1 and Eq. 2 gives:

| (3) |

This ratio is constructed such that explicitly cancels, eliminating the need to determine these quantities and the related systematic uncertainties. The only correction necessary is the conditional probability , which is determined from a full Monte-Carlo simulation of the PHENIX detector indicated by the subscript Sim. The second factor is a ratio of directly measured quantities, indicated by Data. Finally, Eq. 3 can be divided by the fraction of hadron decay photons () per decay photon, which defines as a double ratio:

| (4) |

where the ratio / was determined with a particle-decay generator, indicated by the subscript Gen.

If direct photons are emitted from the collision system in a particular range, will be larger than unity. The denominator in Eq. 4 can be obtained from the PHENIX hadron-decay generator exodus [50], based on the measured spectra. In the following sections, the determination of , , , and / will be discussed separately.

II.2 Determining the inclusive photon sample

The 2010 data samples of (at 39 GeV) and (at 62.4 GeV) MB AuAu collisions were recorded with the two PHENIX central-arm spectrometers, each of which has an acceptance of in azimuthal angle and 0.35 in pseudorapidity. For both collision energies, the MB data sets cover a range of 0%–86% of the interaction cross section. The data sample for 62.4 GeV is large enough so that two centrality classes (0%–20% central collisions, 20%–40% midcentral collisions) could be analyzed separately. The event centrality is categorized by the charge measured in the PHENIX beam-beam counters [51], which are located at a distance of 144 cm from the nominal interaction point in both beam directions, covering the pseudorapidity range of and in azimuth.

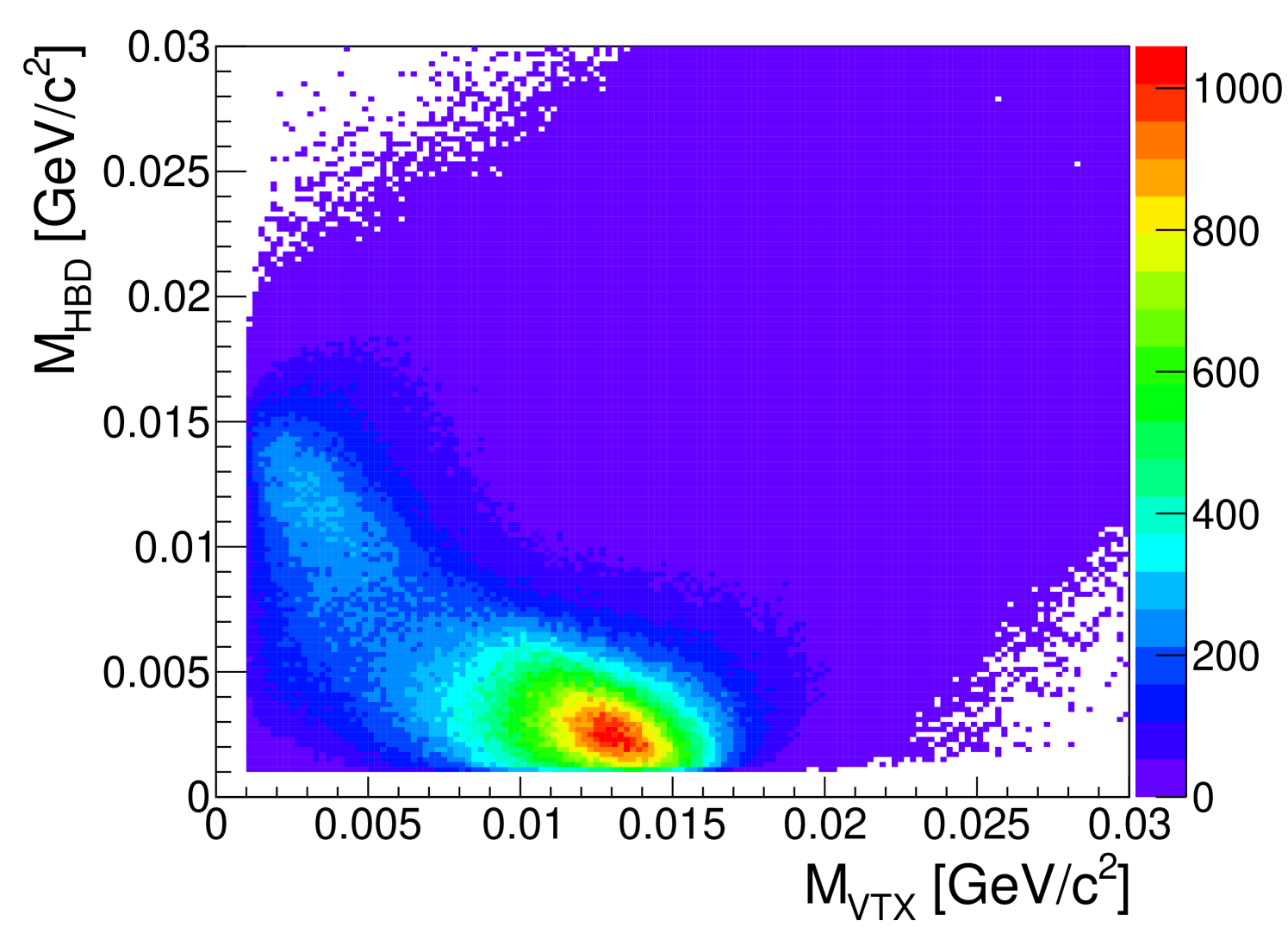

The PHENIX central-arm drift chambers and pad chambers [52], located from 200 to 250 cm radially to the beam axis, are used to determine the trajectories and momenta of charged particles. The momenta are measured assuming the track originated at the event vertex (vtx) and traversed the full magnetic field. The tracks are identified as electrons or positrons by a combination of a minimum signal in the ring-imaging Čerenkov (RICH) detector [53] and a match of the track momentum with the energy measured in the electromagnetic calorimeter (EMCal) [54]. The RICH cut requires that a minimum of three RICH phototubes be matched to the charged track within a radius interval of 3.4 cm 8.4 cm at the expected ring location. For each electron candidate an associated energy measurement in the EMCal is required, with an energy/momentum ratio, E/, greater than 0.5. Electrons and positrons are combined to pairs and further selection cuts are applied to establish a clean sample of photon conversions. Most photon conversions occur in the readout boards and electronics at the back plane of the hadron blind detector (HBD) [55], located at a radius of 60 cm from the nominal beam axis. The relative thickness in terms of radiation length is equal to ; all other material between the beam axis and the drift chamber is significantly thinner. Electrons and positrons from these conversions do not traverse the full magnetic field444A special field configuration was used in 2010 for the operation of the HBD. In this configuration there is a nearly field free region around the beam axis out to 60 cm. Thus the field integral missed by tracks from photon conversions in the HBD back plane is rather small.. Projecting the tracks back to the interaction point results in a small distortion of the reconstructed momenta, both in magnitude and in direction, which in turn results in an artificial opening angle of the pair. This gives the pair an apparent mass (), which depends monotonically on the radial location of the conversion point and is approximately 0.0125 GeV/ for conversions in the HBD back plane.

To select photon conversions in the HBD back plane, the track momenta are re-evaluated assuming the tracks originated at the HBD back plane. For pair from conversions in the HBD back plane, a mass () of below 0.005 GeV/ is calculated with a distribution expected for an pair of zero mass measured with the PHENIX-detector resolution. Figure 2 shows the correlation between the two different masses calculated for each pair. Photon conversions in the HBD back plane are clearly separated from pairs from Dalitz decays, , which populate a region and around 0.012 GeV/. The region between the pairs from Dalitz decays and conversion in the HBD back plane is populated by conversions at radii smaller than 60 cm. To select a clean sample of photon conversions in the HBD back plane, , a two dimensional cut is applied: GeV/ and GeV/. The purity of this photon sample was determined with a full Monte-Carlo simulation and is better than 99%. The sample sizes are and , for 39 and 62.4 GeV, respectively.

II.3 Tagging photons from decays

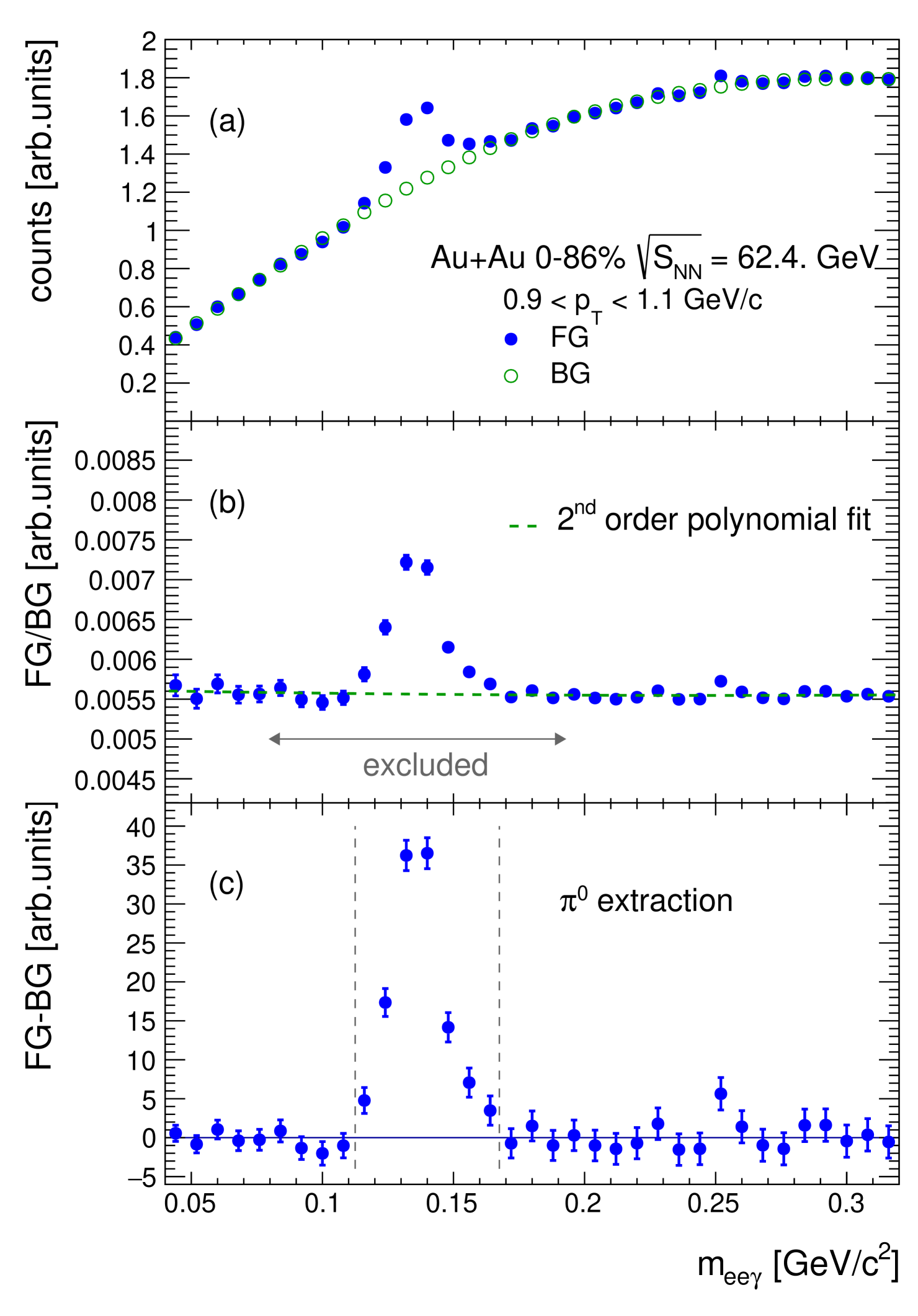

Once the conversion-photon sample is established, all pairs in a given bin are combined with showers reconstructed in the EMCal in the same event and then the invariant mass is calculated. A minimum-energy cut of 0.4 GeV is applied to remove charged particles that leave a minimum-ionizing signal in the EMCal and further reduce the hadron contamination by applying a shower-shape cut. Figure 4(a) shows one example of the resulting mass distributions for a bin around 1 GeV/ from the 62.4-GeV MB data set. The peak is clearly visible above a combinatorial background, which results from combining pairs with all showers in the event, most of which are not correlated with the pair.

A mixed-event technique is used to determine and subtract the mass distribution of these random combinations. In event mixing, all pairs in a given event are combined with the EMCal showers from several other events. These other events are chosen to be in the same 10% centrality selection and within 1 cm of the interaction point of the event with the pair. The ratio of the measured (foreground) mass distribution and mixed event (background) mass distribution is fitted with a 2nd-order polynomial, excluding the mass range GeV/, around the peak. Figure 4(b) shows the ratio and the fit, which is used to normalize the mixed event background distribution over the full mass range; the result is included in Fig. 4(b).

Figure 4(c) depicts the counts remaining after the mixed event background distribution is subtracted from the foreground distribution. The raw yield of tagged is calculated as the sum of all counts in mass window . The counts in two side bands around the peak are evaluated to account for any possible remaining mismatch of the shape of the combinatorial background from mixed events compared to the true shape. These side bands are GeV/ and GeV/. The average counts per mass bin in the side-bands is subtracted from the raw tagged counts, the resulting counts are the number of tagged , in the given bin.

The systematic uncertainties of the peak-extraction procedure were evaluated by choosing different-order polynomial function for the normalization and the various mass windows were varied in the procedure. It is found that changes by less than 8% and 5% for 39 and 62.4 GeV data, respectively. These systematic uncertainties are mostly uncorrelated between bins and thus are added in quadrature to the statistical uncertainties on .

II.4 The conditional tagging probability

The conditional probability , to tag an pair that resulted from a conversion of a decay photon with the second decay photon, depends on the parent spectrum, the decay kinematics, the detector acceptance, and, the photon reconstruction efficiency. A Monte-Carlo method is used to calculate . The method was developed for the direct-photon measurement from AuAu collisions at = 200 GeV, also recorded during 2010, as described in Ref. [35]. The calculation is done separately for MB and centrality selected AuAu collisions at 39 and 62.4 GeV. Each calculation is based on an input spectrum that was measured for the same data sample [56].

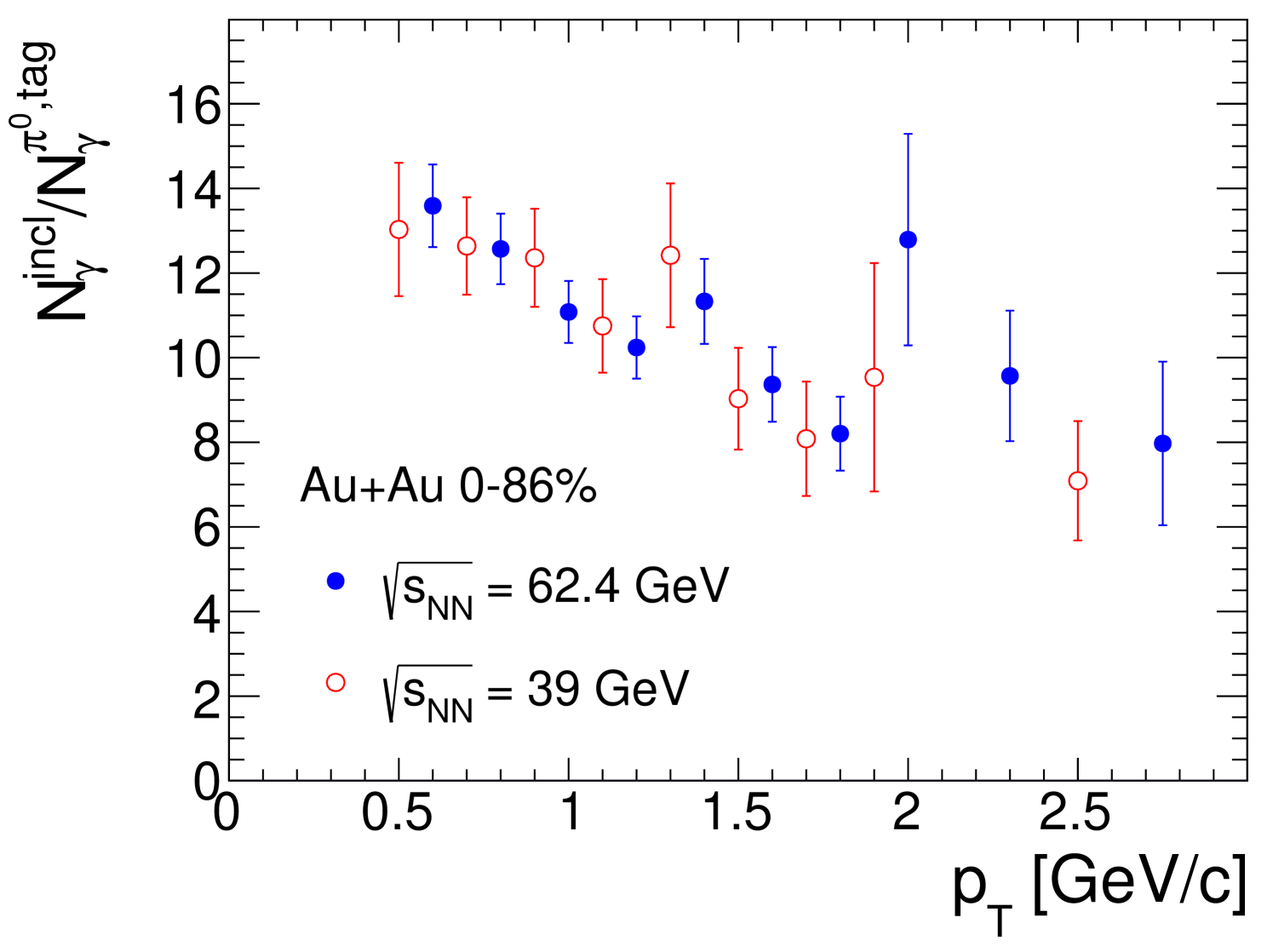

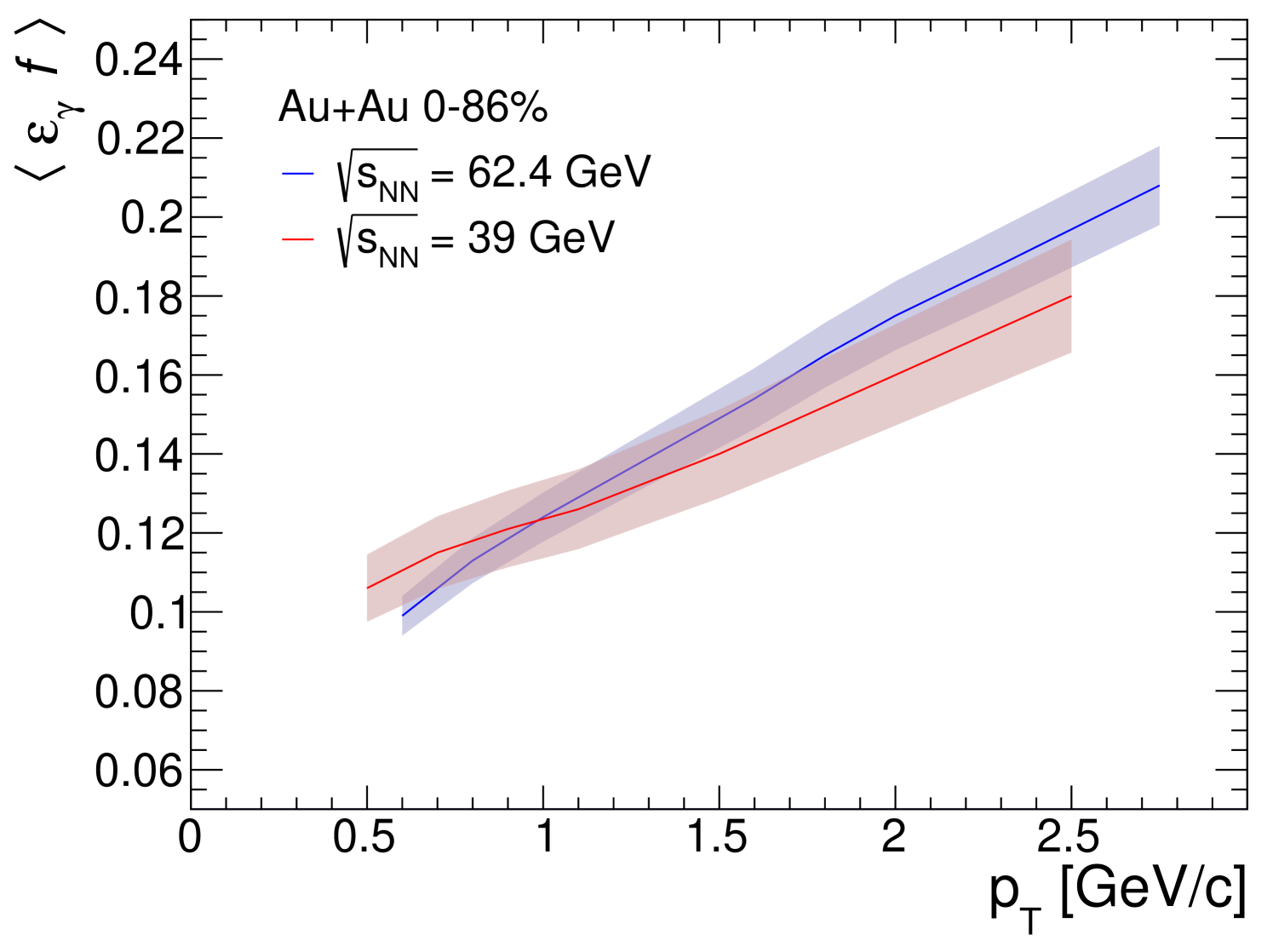

Figure 6 shows the results for MB collisions. The conditional probability is small; it increases from approximately 10% to 20% over the range from 0.8 to 2.5 GeV/. The visible difference between for 39 and 62.4 GeV is due to the dependence of the spectra, which are much softer for the lower energies. Because is evaluated for a fixed range of the pair, it is averaged over all possible . Thus the value of at a fixed pair is sensitive to the parent spectrum.

The EMCal acceptance contributes a multiplicative factor of 0.35 to at an pair = 0.8 GeV/, the factor increases to 0.45 at 2.5 GeV/. This includes the geometrical dimension and the location of the EMCal sectors, the fiducial cuts around the sector boundaries and any dead areas in the EMCal. The minimum-energy cut of 0.4 GeV is the main contributor to the photon-reconstruction efficiency loss. This cut is equivalent to an asymmetry cut on the decay photons; the effect being largest at the lowest momenta that can contribute in a given pair bin. With additional, but small, contributions from the shower-shape cut and the conversion of the second photon, the reconstruction efficiency rises from 0.3 to 0.45 over the range of 0.8 to 2.5 GeV/.

Figure 6 also shows the systematic uncertainties on , which are 8% and 5% for 39 and 62.4 GeV, respectively. The uncertainty of the energy calibration and the accuracy of the spectra are the two dominant sources of systematic uncertainties. A 2% change in the energy calibration, and with it a change of the actual energy cutoff, modifies by 3% to 4%. For 62.4 GeV, the measured spectra agree in shape within 10% with the charged-pion data from STAR [57]. Possible shape variations within this range translate into an uncertainty of 3% on .

For 39 GeV, STAR has published charged-pion data up to 2 GeV/ [58], these data agree in shape with the PHENIX data within 10%. However, due to the limited range, the systematic uncertainties on the shape of the spectrum were determined from the systematic uncertainties of the PHENIX measurement alone, which is less restrictive and, thus, results in a larger uncertainty.

II.5 Decay photons form hadron decays

The ratio of all photons from hadron decays to those from decays, in the denominator of Eq. 3, is the final component that is needed to calculate . In addition to decays of , decays of the , , and mesons contribute to , with the decay being the largest contributor. Any other decays emit a negligible number of photons.

Photons from hadron decays are modeled based on the parent distributions. For each centrality class, the measured spectrum is used to generate s, which are subsequently decayed to photons using the known branching ratios and decay kinematics. The decay photons from , and are modeled similarly, with a parent distribution derived from the measured distributions, assuming scaling (see Refs. [34, 59] for details)555Ref. [59] recently noted that using scaling overestimates the meson yield in collisions for below 2 GeV/. The same work also shows that in AuAu collisions at RHIC energies, this depletion is partially compensated by radial flow, which enhances the yield of in the same region. For this analysis, removing the scaling assumption, while including the effect of radial flow, will reduce the number of photons from hadron decays by 2% for GeV/, where the change is the largest. Correspondingly the direct-photon yield would increase by 2%, which is within the systematic errors of 2.4% quoted on the contribution of / to and much smaller than the overall statistical (7%) and systematic (5%) uncertainties of the measurement at of 1GeV/. The normalization of photons from , , and is set to , and all at GeV/.

II.6 Direct-photon spectra

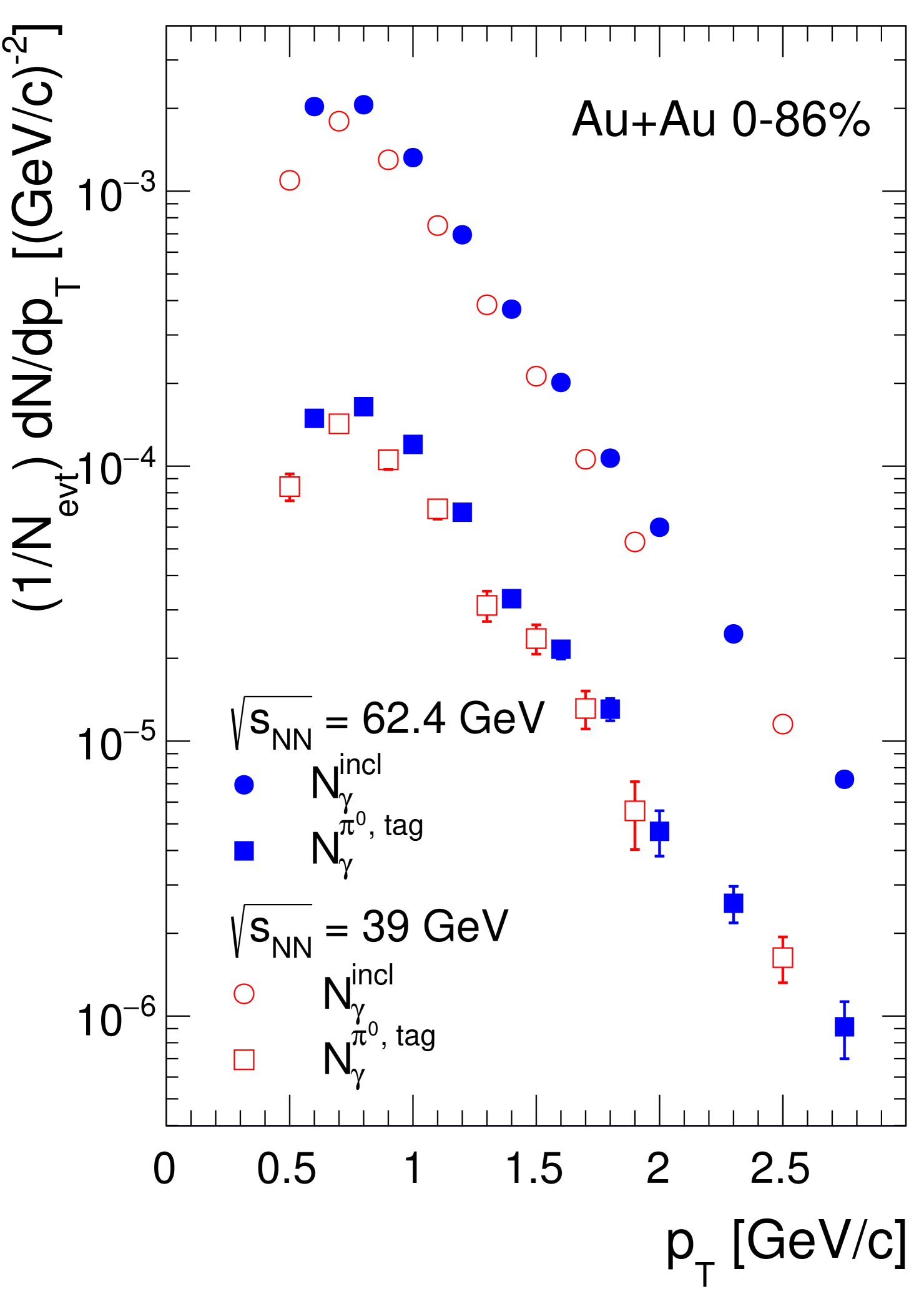

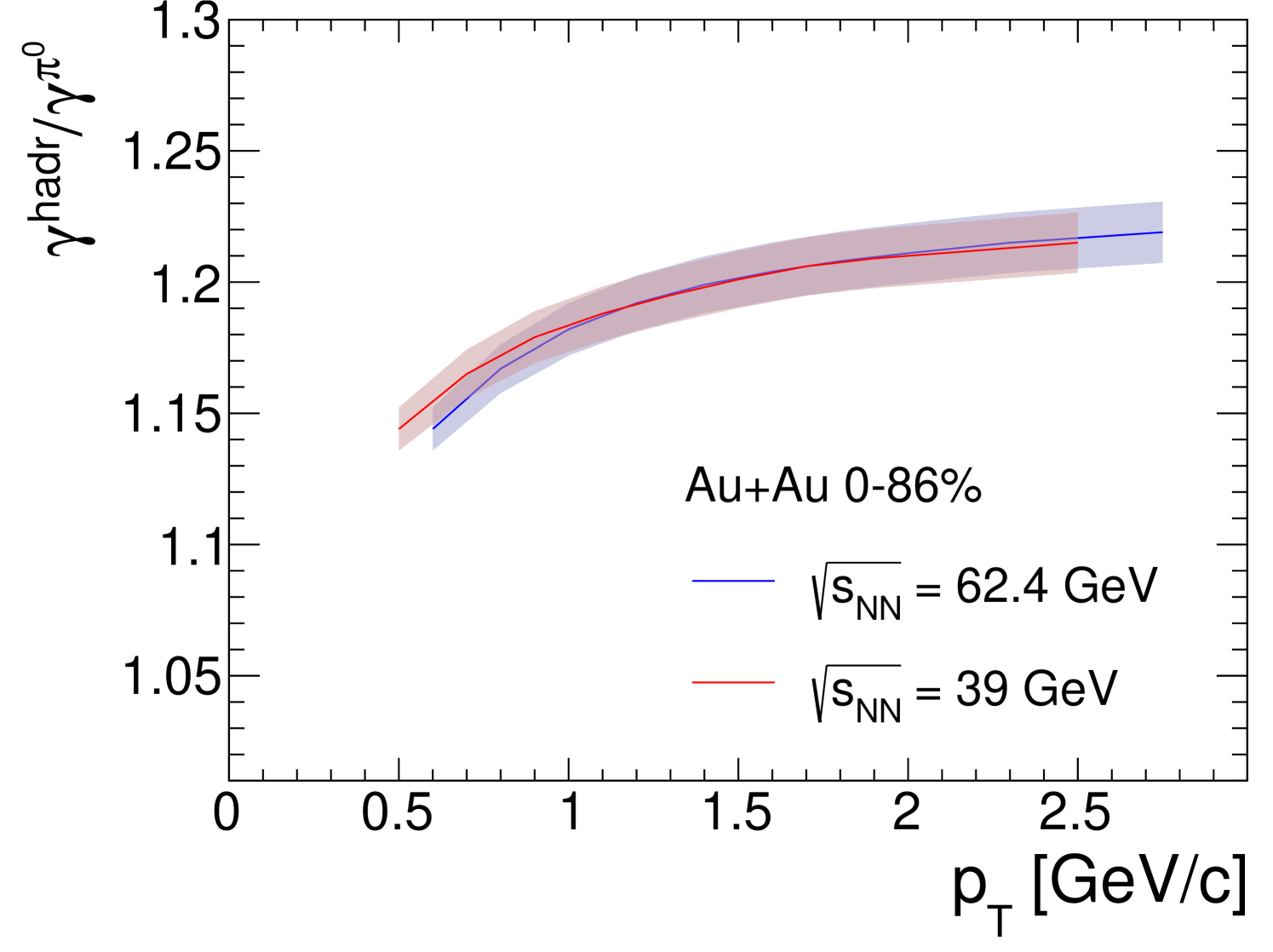

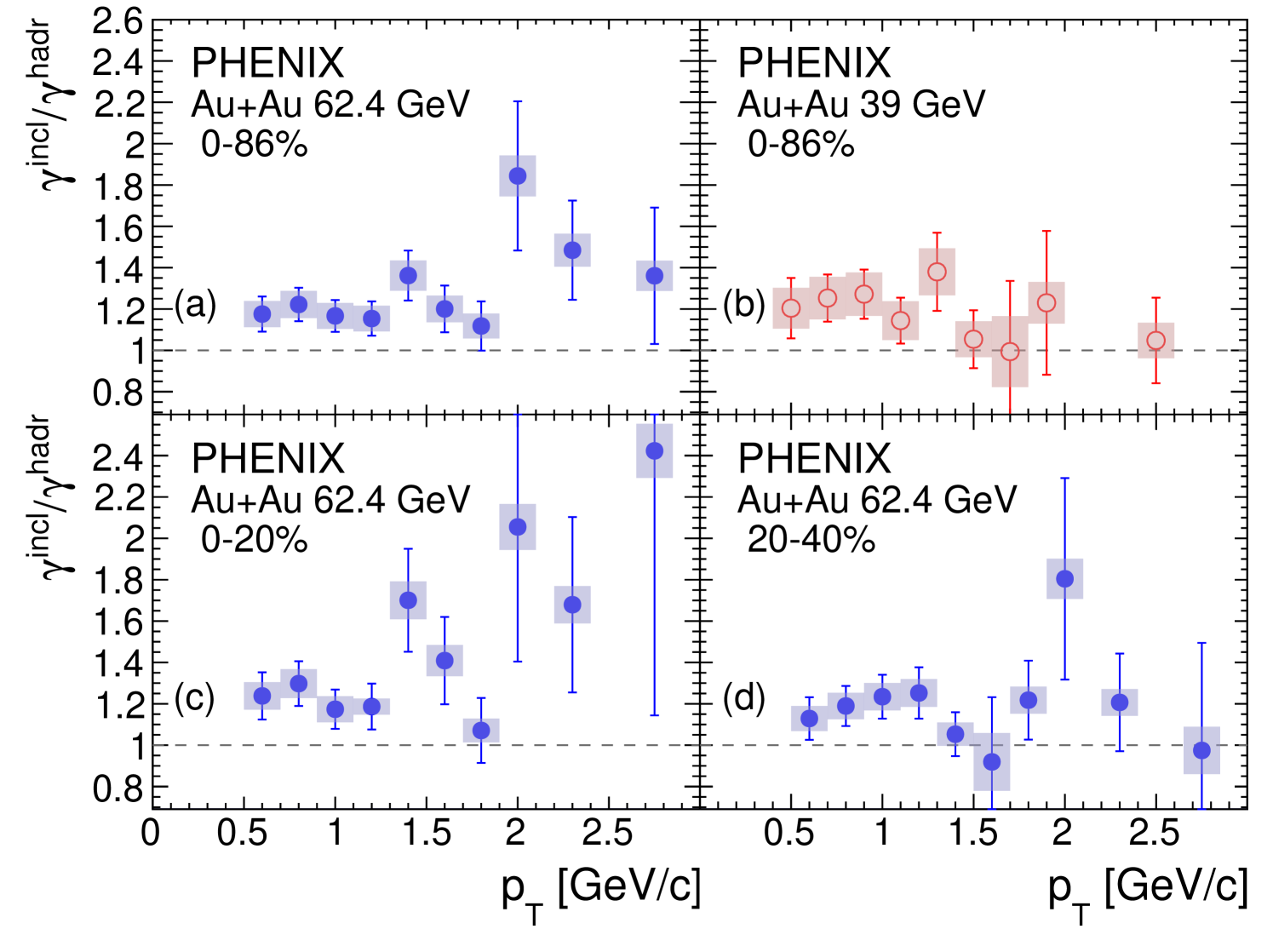

After each factor in Eq. 4 is determined, can be calculated. Figure 8 shows the results for all centrality classes. Despite the significant statistical and systematic uncertainties, the majority of the data points are above unity at a value around . This indicates the presence of a direct-photon component of 20% relative to hadron-decay photons in AuAu collisions at 39 and 62.4 GeV. There is no obvious dependence over the observed range; furthermore, the and centrality dependence, if any, must be small.

To further analyze the data is converted to a direct-photon spectrum using the hadron-decay-photon spectra calculated in Sec. II.5:

| (5) |

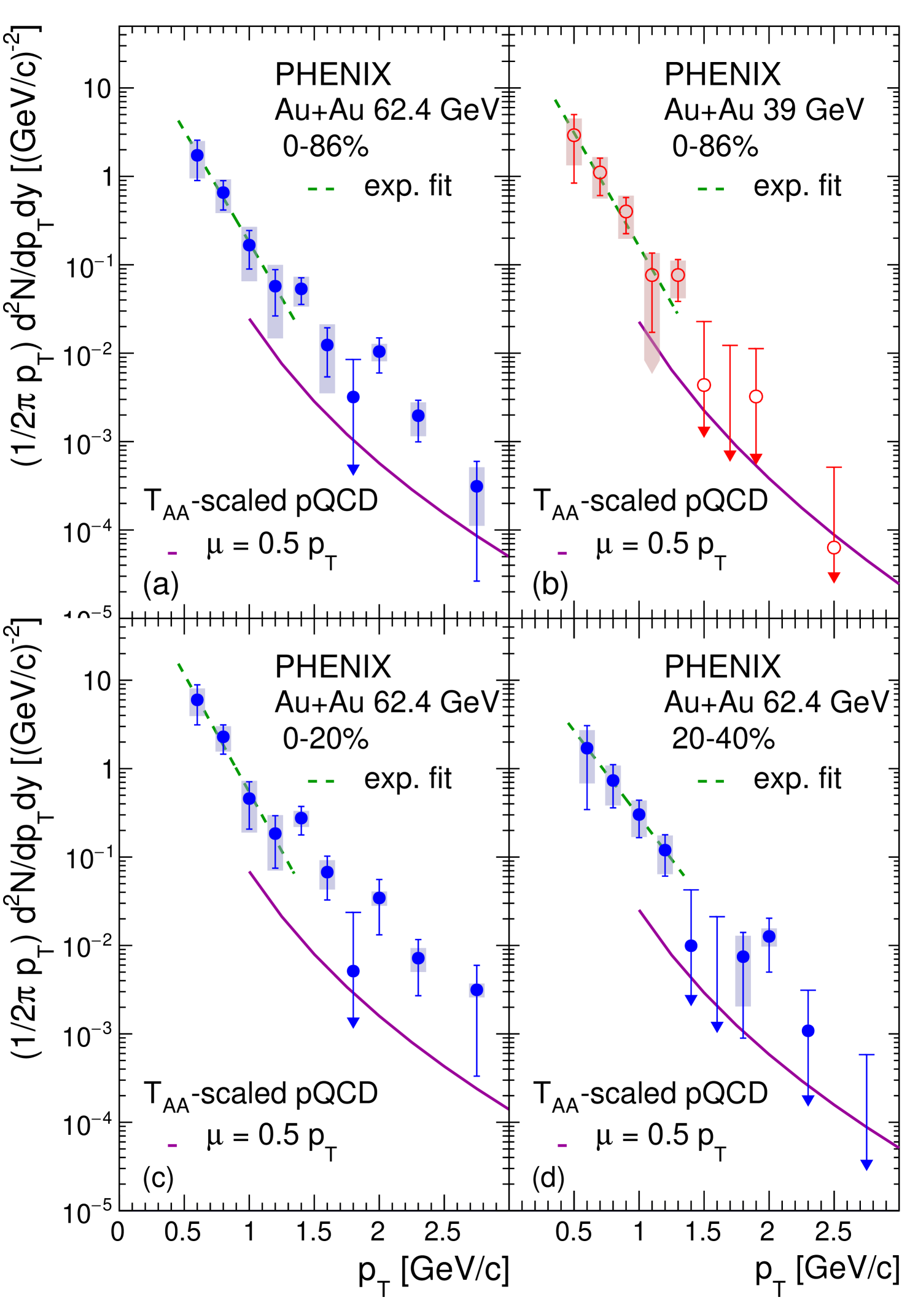

Figure 9 presents the calculated direct-photon spectra. In addition to the systematic uncertainty on , the hadron-decay-photon spectra contribute 10% to the systematic uncertainties. These uncertainties cancel in , but need to be considered here. Each centrality and energy selection is compared to the expected prompt-photon contribution from hard-scattering processes based on perturbative-quantum-chomodynamics (pQCD) calculations from [10, 60]. Shown are the calculations at the scale , which were extrapolated down to GeV/. The scale was selected as it typically gives a good description of prompt-photon measurements in collisions (see also Fig. 10). To represent hard scattering in AuAu collisions, the calculation is multiplied with the nuclear-overlap function for the given event selection [61], assuming an inelastic cross sections of mb at 39 GeV mb at 62.4 GeV. Table 1 gives the values. Below 1.5 GeV/, there is a clear enhancement of the data above the scaled pQCD calculation, consistent with the expectation of a significant thermal contribution.

| Centrality-class | ||

| (GeV) | selection | (mb-1) |

| 62.4 | 0%–20% | 18.44 2.49 |

| 62.4 | 20%–40% | 6.77 0.82 |

| 62.4 | 0%–86% | 6.59 0.89 |

| 39 | 0%–86% | 6.76 1.08 |

To characterize the enhancement, the data is fitted with a falling exponential function given by

| (6) |

The data sets were fitted below a of 1.3 GeV/, where statistics are sufficient. Table 2 summarizes the results, which are also shown in Fig. 9. Systematic uncertainties were obtained with the conservative assumption that the uncertainties are anticorrelatated over the observed range. All values are consistent with a common inverse slope of 0.170 GeV/. For the MB and 0%–20% centrality AuAu sample at 62.4 GeV, the data in the range from 0.9 to 2.1 GeV/ is also fitted. The values are slightly above 0.24 GeV/ and are larger than the value extracted for the lower- range. A possible increase of with is consistent with the values obtained from AuAu at 200 GeV [35] and PbPb at 2.76 TeV [39], which were fitted in the higher- range. See a more detailed discussion in the next section.

| Centrality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (GeV/) | (GeV) | class | (GeV/) | |

| 62.4 | 0%–20% | 0.163 0.031 | 0.44/2 | |

| 62.4 | 20%–40% | 0.224 0.067 | 0.01/2 | |

| 62.4 | 0%–86% | 0.172 0.032 | 0.16/2 | |

| 39 | 0%–86% | 0.169 0.035 | 0.41/2 | |

| 62.4 | 0%–20% | 0.241 0.048 | 6.96/4 | |

| 62.4 | 0%–86% | 0.245 0.046 | 5.61/4 |

III Comparison to Direct-Photon Measurements from higher collision energies

In this section, the direct-photon results from AuAu collisions at 39 and 62.4 GeV are discussed in the context of other direct-photon measurements from heavy ion collisions at higher collision energies, specifically AuAu collisions at 200 GeV from RHIC and PbPb collisions at 2.76 TeV from LHC. The discussion is divided into three parts. The first part recalls the already published scaling behavior of the direct photon yield with [40]. The next part takes a closer look at the and dependence of the inverse slope of the direct-photon spectra. The last part investigates the dependence or independence of the scaling variable on the range.

| Collision system | (GeV) | Centrality class | Collaboration [Ref.] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 62.4 | - | 1 | UA5 [62, 63, 64] | ||

| 200 | - | 1 | PHENIX [61] | ||

| 2760 | - | 1 | ALICE [65] | ||

| CuCu | 200 | 0%–40% | PHENIX [61] | ||

| 200 | 0%–94% | ” | |||

| AuAu | 39 | 0%–86% | PHENIX [61] | ||

| 62.4 | 0%–86% | ” | |||

| 62.4 | 0%–20% | ” | |||

| 62.4 | 20%–40% | ” | |||

| 200 | 0%–20% | ” | |||

| 200 | 20%–40% | ” | |||

| 200 | 40%–60% | ” | |||

| 200 | 60%–92% | ” | |||

| PbPb | 2760 | 0%–20% | ALICE [66] | ||

| 2760 | 20%–40% | ” | |||

| 2760 | 40%–80% | ” |

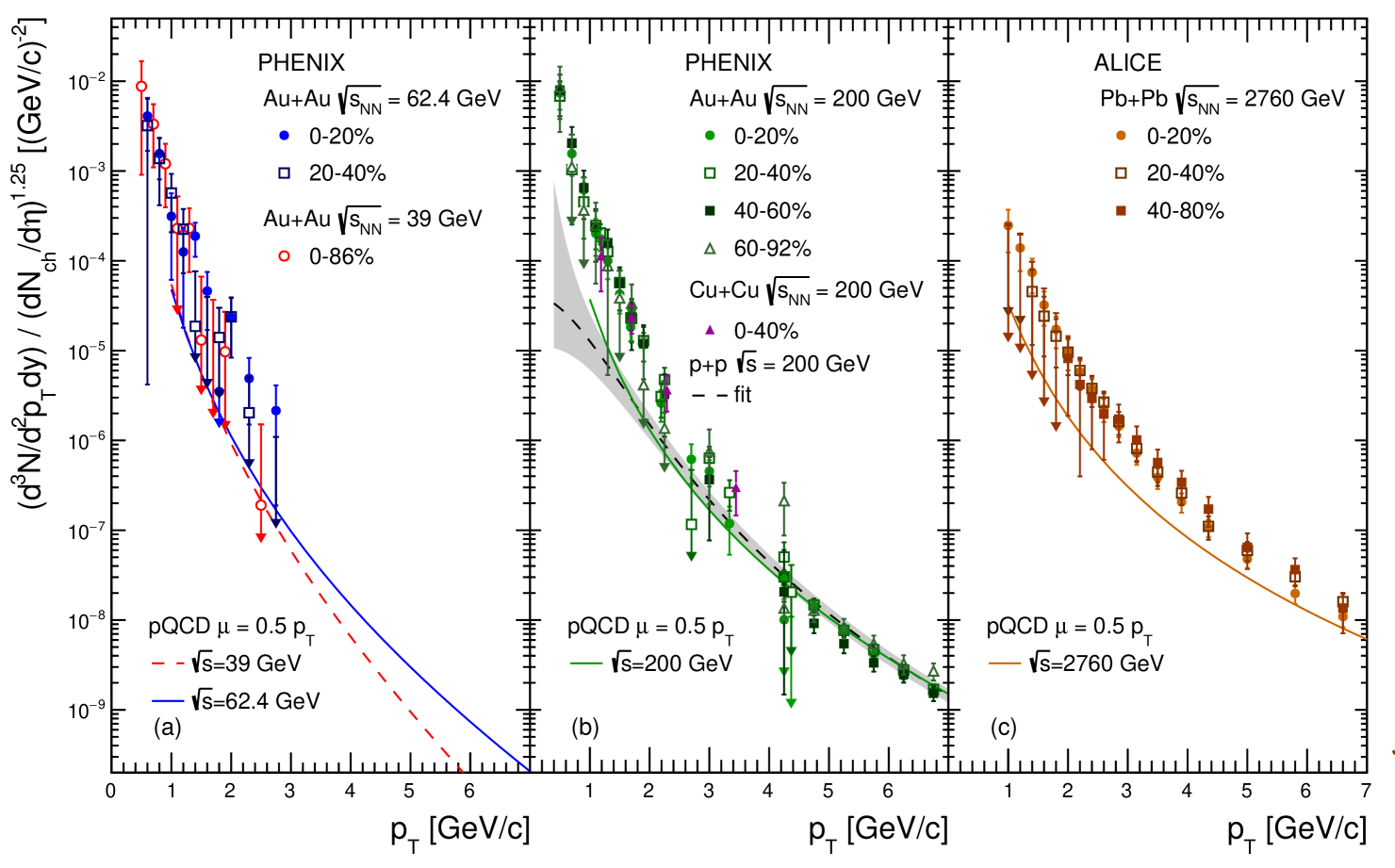

III.1 Scaling of the direct-photon yield with

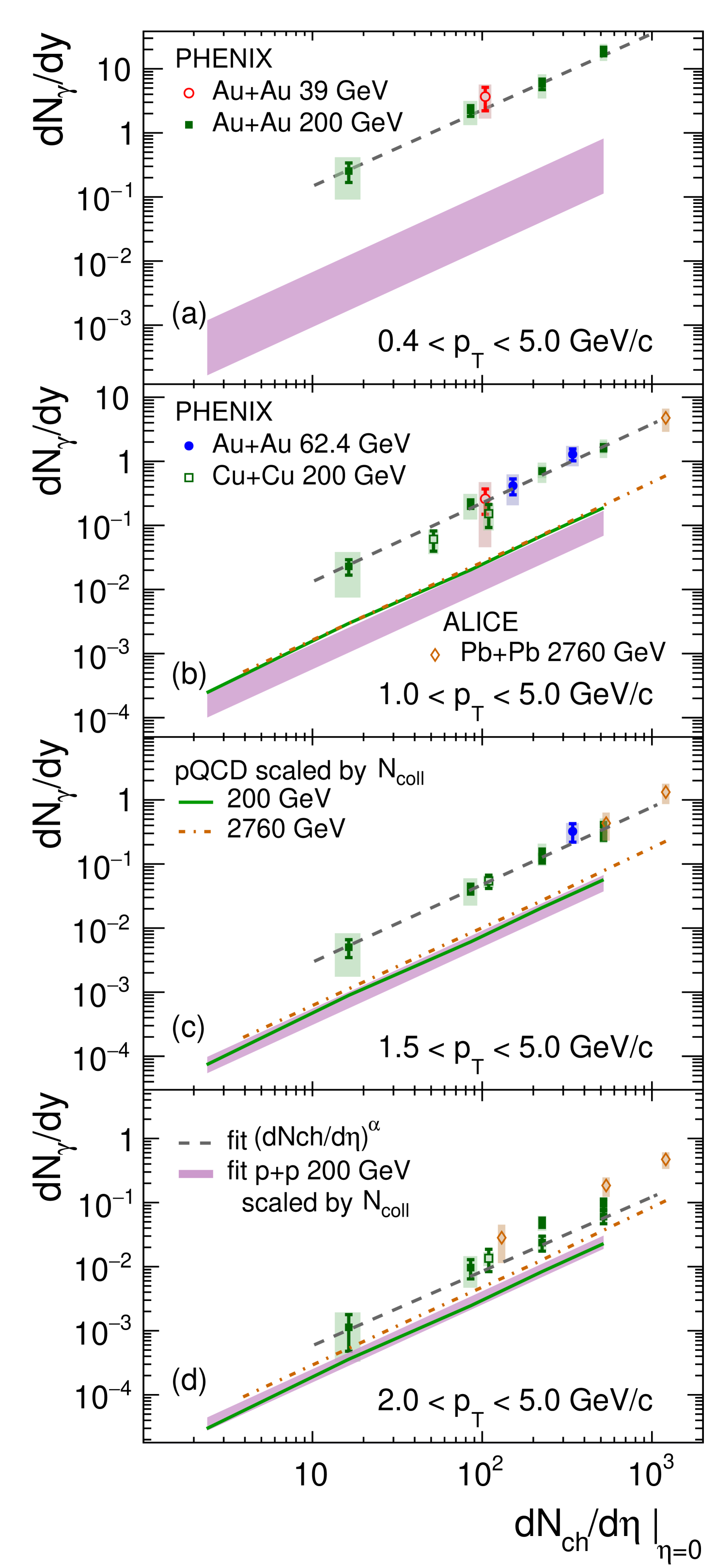

It was shown in Ref. [40] that the direct-photon yield from heavy ion collisions is approximately proportional to with common power across collision energies, systems, and centrality. Figure 10 presents the direct-photon yield normalized to for a large range of data sets666The WA98 data are not shown here and in the following plots. The upper limits from WA98 for GeV/ are consistent with the lower end of the uncertainties of the PHENIX 62.4 GeV and 39 GeV data, but they do not significantly constrain the scaling behavior at low . The STAR data are also not shown as the tension with the PHENIX data remains unresolved, while the multiple publications from PHENIX, based on different data sets and analysis methods, show self consistent results. If taken at face value, the STAR data do demonstrate a similar scaling behavior with for GeV/, but at a factor-3-lower direct-photon yield.. Panel (a) shows the data sets that are derived from the AuAu measurements at 39 and 62.4 GeV shown in Fig. 9. Panel (b) presents PHENIX measurements from AuAu [41, 34, 35] and CuCu [47] collisions at = 200 GeV. Panel (c) uses the ALICE measurement from PbPb collisions at = 2760 GeV [39]. All panels show pQCD calculations for collisions at the corresponding , extrapolated to = 1 GeV/ at the scale [10, 60].

Table 3 gives the and values, which are are used to normalize the integrated yields and are obtained from published experimental data. The values for collisions at 62.4 are taken from Fig. 52.1 of Ref. [62], which was interpolated between UA5 data at = 53 GeV [63] and 200 GeV [64]. The values for and heavy ion collisions from = 7.7 GeV to 200 GeV are from PHENIX [61]; the values for 2760 GeV data are from ALICE [65]; and the values for PbPb collision data at 2760 GeV are also from ALICE [66].

where the parameters are (GeV/)-2, GeV/ and . The band represents the uncertainty of the fit.

All three panels in Fig. 10 show that at a given the normalized direct-photon yield from AA collisions is independent of the collision centrality. This is true both for low and high . Comparing the yield at below 3–4 GeV/ across panels reveals that the yield is also remarkably independent of . Above of 4 to 5 GeV/ the normalized yield does show the expected dependence and is described by the pQCD calculations.

In the high- range, hard-scattering processes dominate direct-photon production, and these direct-photon contributions are not altered significantly by final-state effects. Different centrality selections show the same normalized yield, which reflects that empirically [40]. It remains surprising that within uncertainties the same scaling also holds at lower where direct-photon emission should be dominated by thermal radiation from the fireball. In the following sections, the similarity of the low- direct-photon spectra, both in shape and in normalized yield, is analyzed more quantitatively.

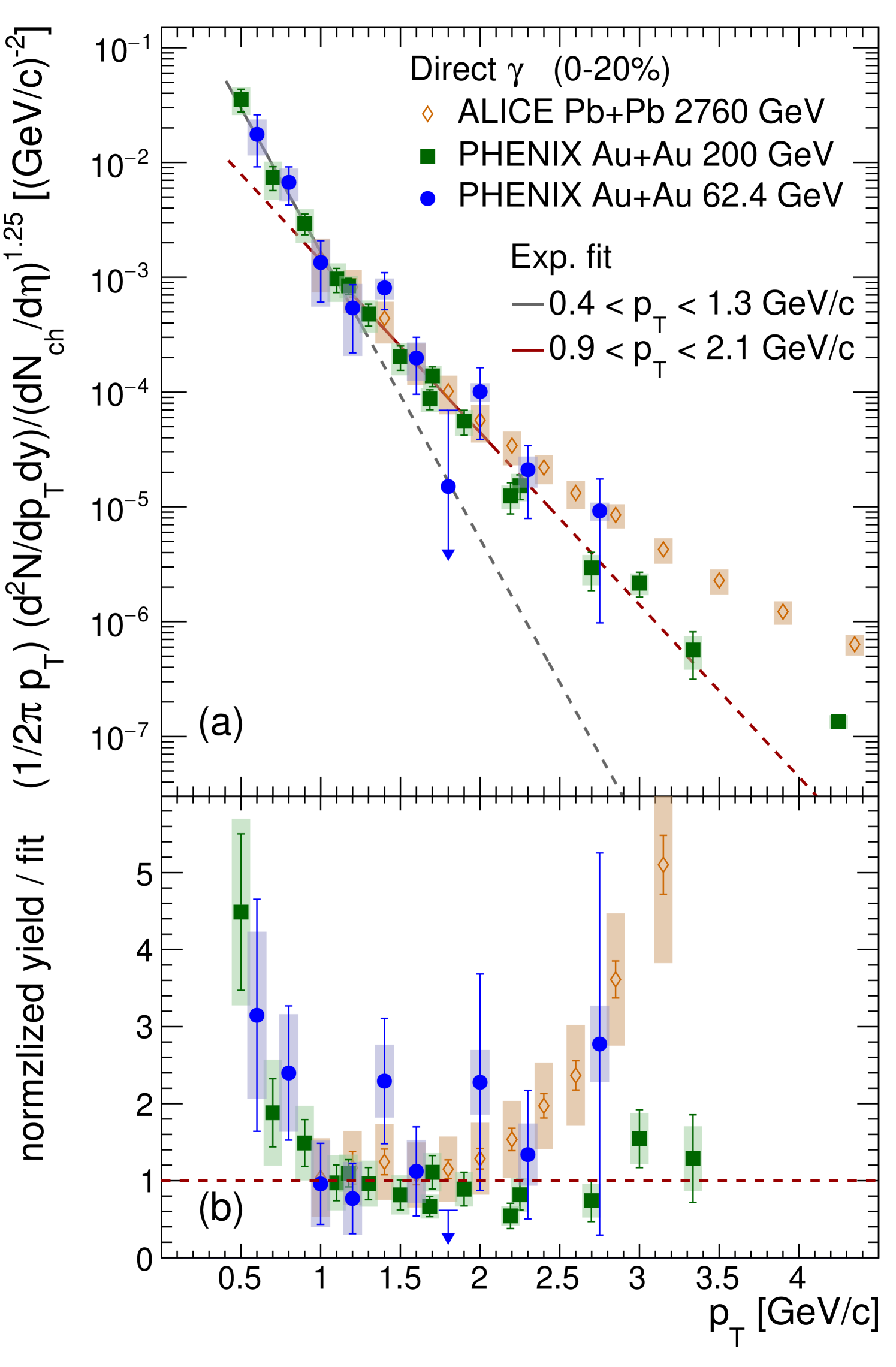

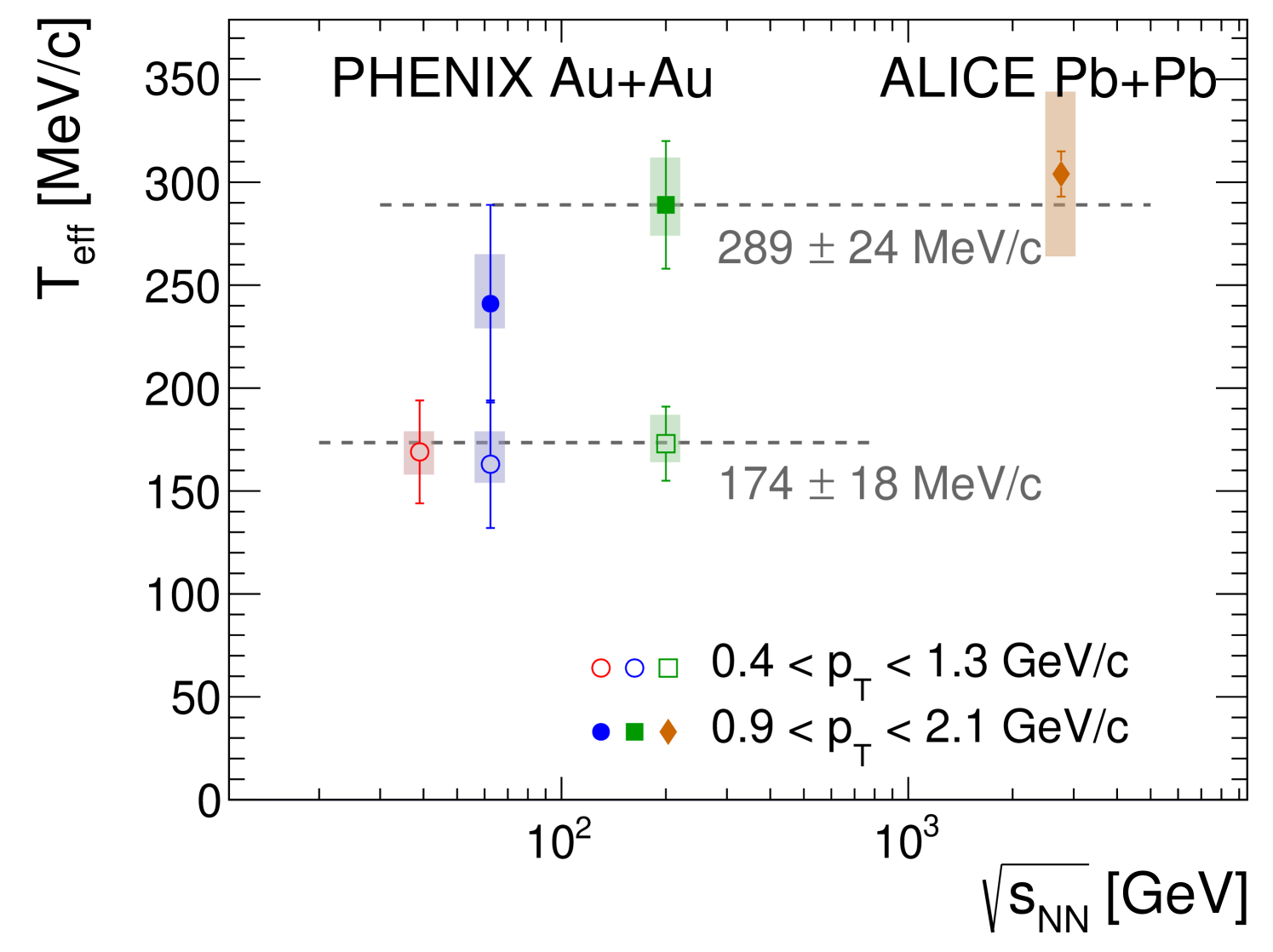

III.2 Direct-photon inverse slope

To better reveal the similarity of the low- direct-photon spectra across , the normalized yield from the most-central samples (0%–20%) for PbPb at = 2760 GeV, AuAu at 200 GeV, and AuAu at 62.4 GeV are superimposed on Fig. 11(a). Below 2.5 GeV/, the data agree very well, even though they span almost two orders of magnitude in . As already suggested earlier by exponential fits to the 39 and 62.4 GeV data, the low- direct-photon spectra cannot be described by a single inverse slope, but seem consistent with an inverse slope that increases with . Fitting all data shown in the range GeV/ and GeV/ results in inverse slopes of GeV/ and GeV/, respectively. Here the statistical and systematic uncertainties were added in quadrature in the fitting procedure. The fits are also shown in Fig. 11, where the dashed lines extrapolate the fits over the full range.

Figure 12 compares the inverse slopes from the common fit to the fits of the individual data sets. For = 62.4 GeV, the values are from Table 2, for 200 GeV the data [34, 35] were fitted in the two ranges, and for 2760 GeV the value published in Ref. [66] is shown. For the lower- range a value for MB collisions at = 39 GeV is also included.

Another way to illustrate the commonality of the spectra is to compare the ratio of the normalized yield divided by the extrapolated fit for GeV/. The result is shown in Fig. 11(b). Within the uncertainties the ratios are consistent with unity over the fit range for all three . Below 1 GeV/, where there is no data from = 2760 GeV, the other two energies also agree very well.

The similarity of the spectra in the range up to 2 GeV/ indicates that the source that emits these photons must be very similar, independent of , a finding that would be consistent with radiation from an expanding and cooling fireball evolving through the transition region from QGP to a hadron gas till kinetic freeze-out. This would naturally occur at the same temperature and similar expansion velocity, independent of the initial conditions created in the collisions.

Above 2 GeV/, the normalized direct-photon yield becomes dependent. The = 200 GeV AuAu data remain consistent with the exponential fit until GeV/, where prompt-photon production from hard-scattering processes starts to dominate (see Fig. 10). In contrast, the PbPb data from = 2760 GeV begin to exceed the exponential GeV/, while prompt-photon production only becomes the main photon source above 4 to 5 GeV/, where the -scaled pQCD calculation describes the heavy ion data well.

This leaves room for additional contributions to the direct-photon spectrum in the range from 2 to 5 GeV/ beyond prompt-photon production, which are dependent. Such contributions could reflect the increasing initial temperature that would be expected with increasing collision energy.

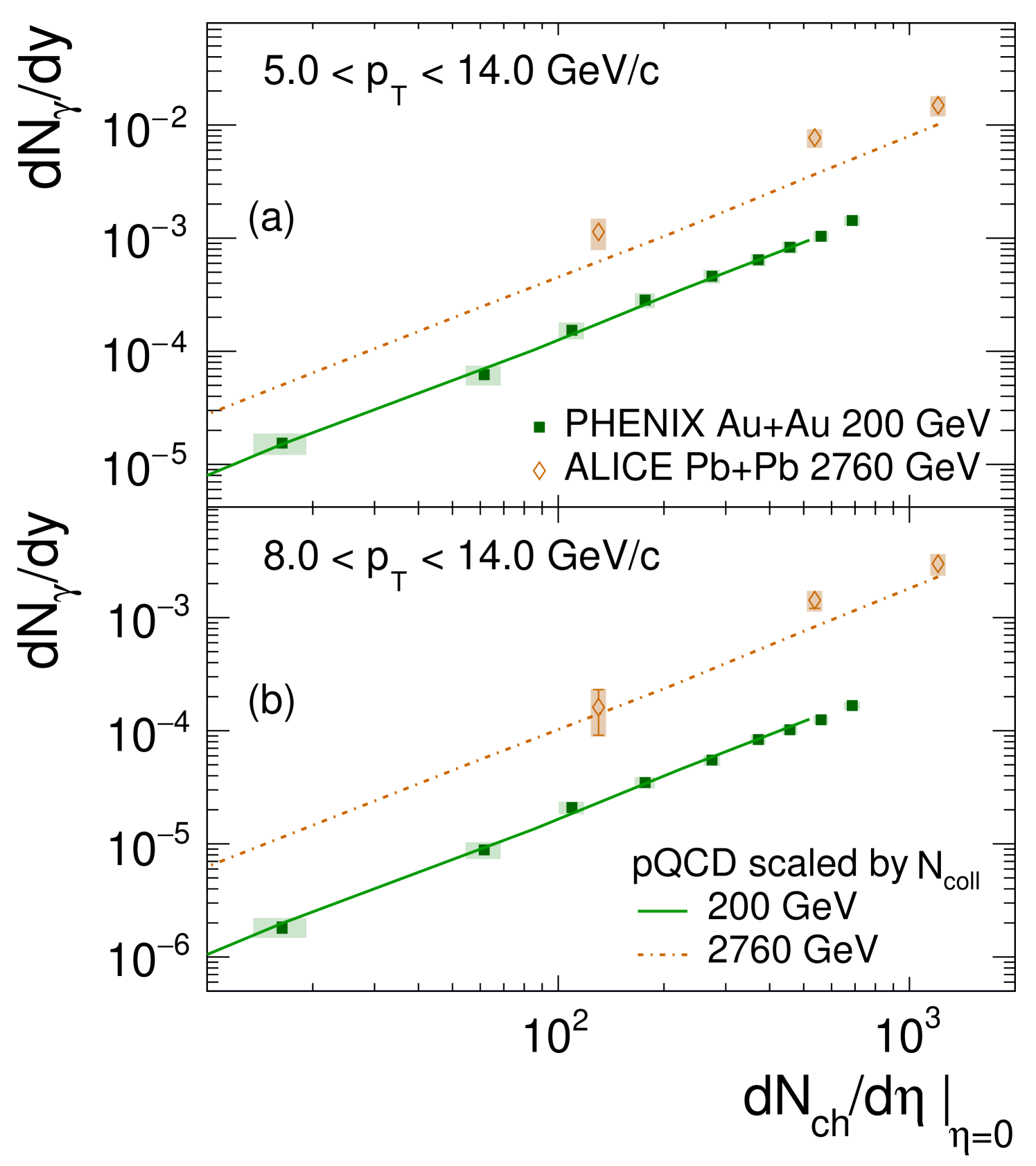

III.3 dependence of the scaling variable

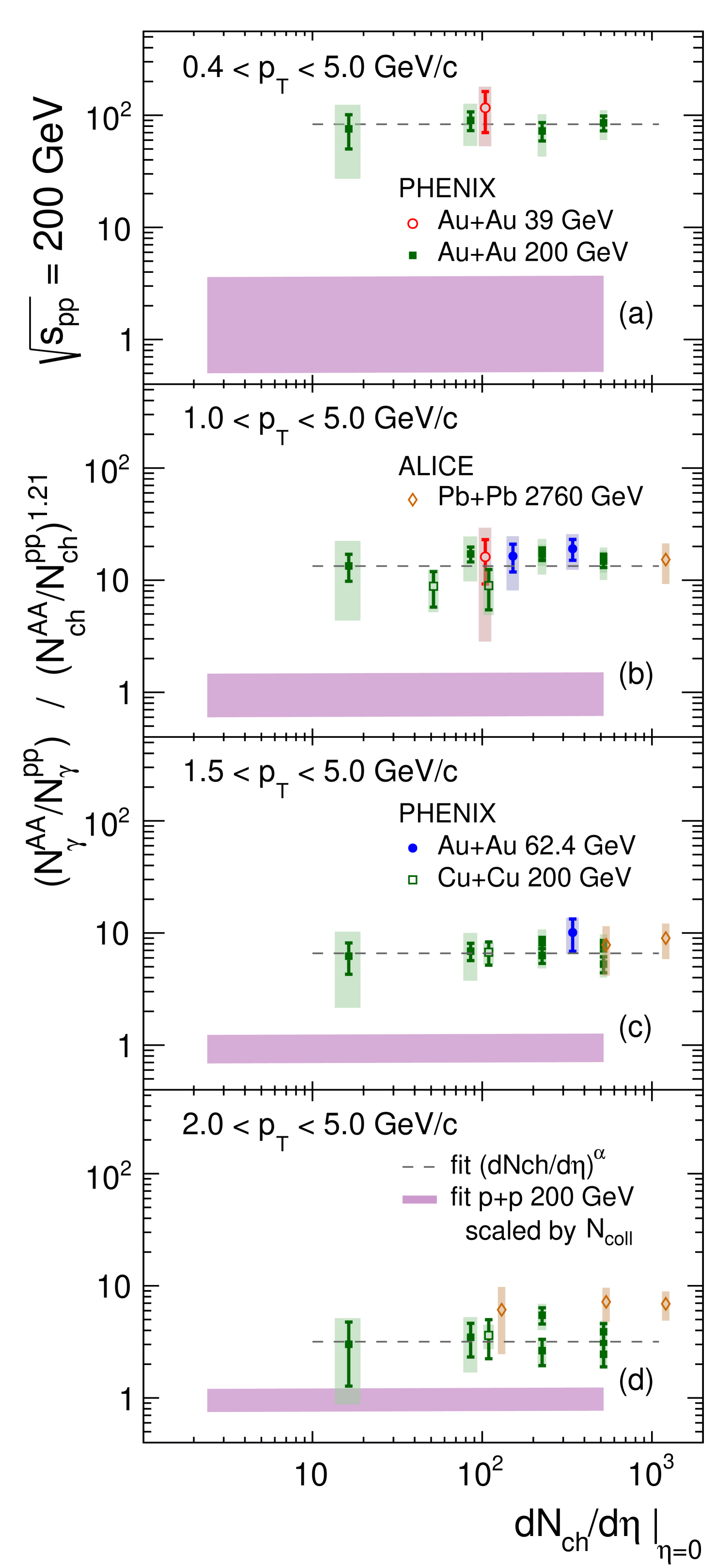

In this final section, the scaling behavior of the direct-photon yield with will be revisited. So far, a fixed value of was used to calculate the normalized inclusive direct-photon yield. This value was obtained from the scaling relation [40]. Here, will be determined from the direct-photon data itself as a function of . For this purpose, the direct-photon spectra are integrated above a minimum value () of 0.4 GeV/, 1.0 GeV/, 1.5 GeV/, and 2.0 GeV/. Panels (a) to (d) of Fig. 14 show the integrated yields as a function of for all data sets shown in Fig. 10. The systematic uncertainties, shown as boxes, give the uncertainty on the integrated yield and the uncertainty on . The AA data are compared to a band representing the integrated yields obtained from the fit to the data at = 200 GeV, with the functional form given in Eq. 7, scaled by . The width of the band is given by the uncertainties on the fit and on , combined quadratically. Panels (b) to (c) also show the integrated yields from the -scaled pQCD calculations for = 200 and 2760 GeV.

| GeV/ | GeV/ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.4 | 5.0 | 1.18/3 | ||

| 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.27/8 | ||

| 1.5 | 5.0 | 6.50/6 | ||

| 2.0 | 5.0 | 8.85/5 | ||

| 5.0 | 14.0 | 2.839/7 | ||

| 8.0 | 14.0 | 2.362/7 |

It is clear from Fig. 10 that all AA data follow a similar common trend. The PHENIX data in each panel of Fig. 14 is fitted with the scaling relation:

| (8) |

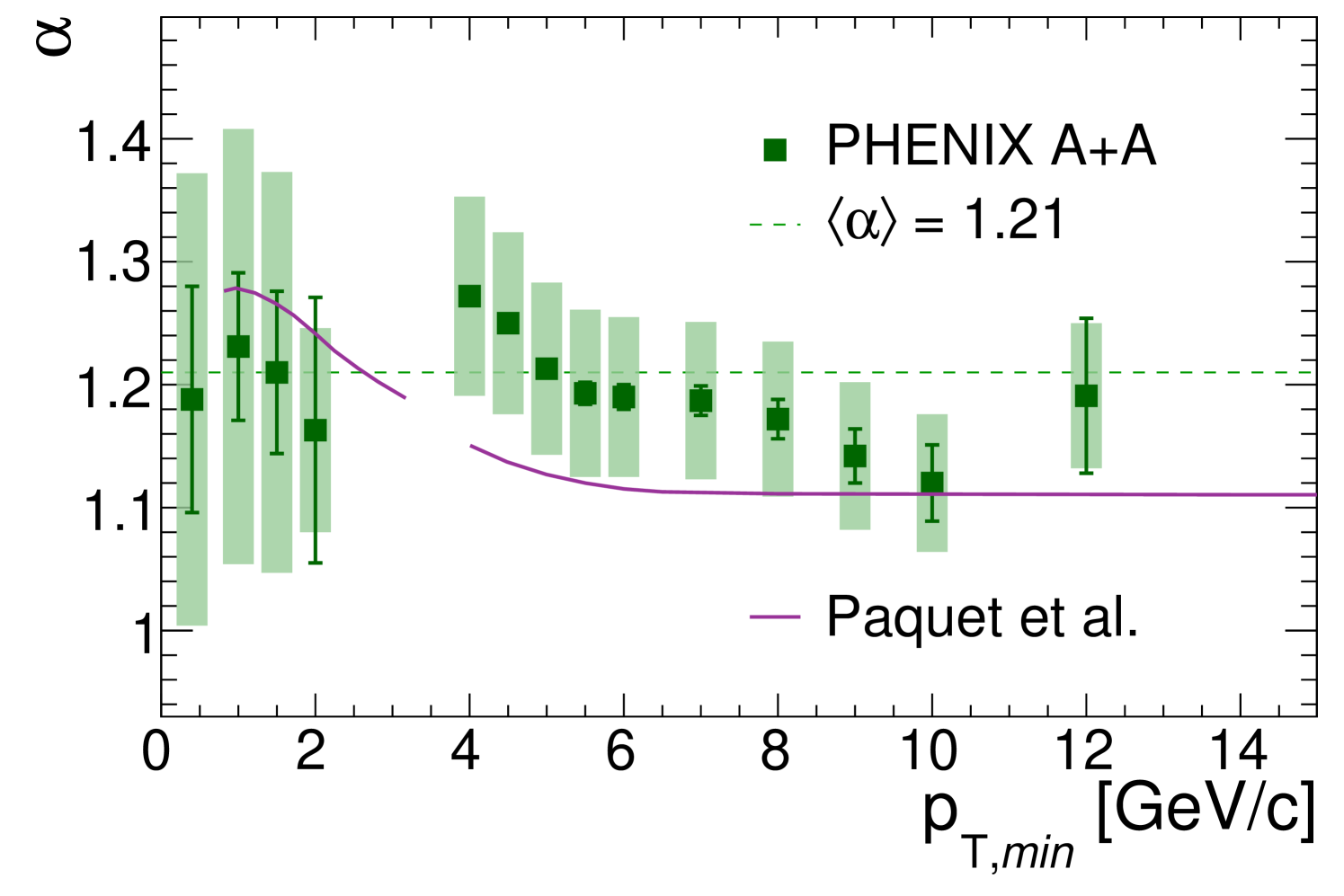

The fit results for are shown as dashed lines in Fig. 10; the fit parameters are given in Table 4. Here the dominant systematic uncertainties are due to occupancy dependent differences in the energy scale calibration and on . It is assumed that within a given data set these could be anti-correlated and that they are uncorrelated between different data sets. The values are consistent with an average value of , with no evident dependence on . The value is consistent, but slightly lower, than .

Figure 14 shows the integrated yield from AA collisions divided by the scaled integrated yield normalized by . In this representation, the bands bracket unity with no visible slope. For high the vertical scale would be equivalent to the nuclear-modification factor of prompt photons. For = 0.4, 1.0, and 1.5 GeV/ all AA data have the same absolute value, within statistical and systematic uncertainties, but are significantly enhanced compared to the band. In particular, the PbPb data at = 2760 GeV also shows the same value in panels (b) and (c), even though they were not included in the fit. The enhancement above drops from nearly two orders of magnitude to a factor of 7 with increasing . In panel (d) for the 2 GeV/ threshold the = 200 GeV data also have the same value, with an enhancement of 3. The PbPb data at = 2760 GeV, while also being independent of , have a value roughly 30% higher than the 200 GeV data. This illustrates the breakdown of the scaling towards higher , at a for which prompt-photon production is not yet expected to be the dominant source. As can be seen from Fig. 14, in this region the PbPb integrated yield exceeds by a factor of 4 to 5 what is calculated by pQCD for prompt-photon production.

With increasing the integrated yield becomes increasingly sensitive to the prompt-photon contribution. Integrated direct-photon yields for the ranges GeV/ and GeV/ are shown in panels (a) and (b) of Fig. 15, together with the corresponding values based on pQCD calculations for the same collision energies. For the integrated yields from AuAu at 200 GeV, the enhancement compared to has vanished and the measured yield is dominated by prompt-photon production, following closely the scaled and integrated yield calculated by pQCD. Fitting the data with Eq. 8 results in slope values of and . The full set of fit parameters are given in Table. 4. Even though the direct-photon yield is dominated by prompt-photon production the slope values are consistent with those found at lower .

The PbPb data at 2760 GeV continue to be enhanced compared to the pQCD calculations even out to of 8 GeV/. The enhancement decreases with and is 50% at = 5 GeV/ and reduces to less than 30% for 8 GeV/. Given the systematic uncertainties on the data and the pQCD calculation these values may already be consistent [39]. Irrespective of whether in addition to prompt-photon production another source is needed to account for the data, the PbPb data can also be well described by a fit with Eq. 8 with and , for GeV/ and 8 GeV/, respectively. These values are consistent with values given in Table 4, within the quoted statistical errors.

Figure 16 presents the values of listed in Table 4, which were obtained from the PHENIX AA data as function of . Also shown in Fig. 16 are values from similar fits for several other values of GeV/ to integrated direct-photon yields from AuAu data at = 200 GeV published in [35]. Within systematic uncertainties, all values are consistent with an average value of 1.21 for the thresholds below 4 GeV/, which is shown as a dashed line.

There is no evidence for a dependence of on .

Figure 16 compares the data to extracted from theoretical model calculations of direct-photon radiation [67, 68]. The model calculation includes prompt-photon production, radiation from the pre-equilibrium phase, and thermal photons emitted during the evolution from QGP to hadron gas to freeze-out. As discussed in the introduction, in general these and similar calculations qualitatively reproduce the large direct-photon yield and the large anisotropy with respect to the reaction plane observed experimentally, but falls short of a simultaneous quantitative description. Similarly, the model calculation shown in Fig. 16 does not fully describe the dependence of on . In the region where thermal radiation is expected to be significant, below = 2 GeV/, the calculated values are consistent with data, but the calculation predicts a dependence of which is not seen in the data. In the model calculation, the thermal-photon contribution from the QGP phase depends on with a higher power of than the later stage contribution from the hadron gas . The dependence of the prompt contribution is similar to the one from the hadron gas. The dominant sources of direct-photon emission change with increasing from hadron gas to QGP to prompt-photon production, and therefore would be expected to depend on . While the data do not show such a dependence, the uncertainties, in particular systematic uncertainties, are too large to rule out that does change with .

IV Summary

The PHENIX Collaboration presented the measurement of low direct-photon production in MB data samples of AuAu collisions at 39 and 62.4 GeV recorded at RHIC in 2010. The measurements were performed using the PHENIX central arms to detect photon conversions to pairs in the back plane of the HBD, following the technique outlined in Ref. [35] for the analysis of low-momentum direct photons in AuAu collisions at 200 GeV. In addition to the MB data samples, the 62.4 GeV/ data was subdivided into two centrality classes, 0%–20% and 20%–40%. For all samples, the relative direct-photon yield, , was obtained through a double ratio in which many sources of systematic uncertainties cancel. In the range from 0.4 to 3 GeV/, a clear direct-photon signal is found for all event selections, which significantly exceeds the expectations from prompt-photon production.

The direct-photon spectra are not described by one exponential function, but are consistent with a local inverse slope increasing with . Comparing the 39 and 62.4 GeV data to direct-photon data from AuAu collisions at = 200 GeV, also measured by PHENIX, and PbPb collisions at = 2760 GeV, published by ALICE, reveals that the local inverse slopes and the shape of the spectra below 2 GeV/ are independent of and centrality of the event sample. The combined data for central collisions were fitted with an exponential in the range below 1.3 GeV/. The inverse slope value found is GeV/. The range from 0.9 to 2.1 GeV/ was also fitted with an exponential function. The inverse slope is significantly larger, with a value of GeV/.

Furthermore, the invariant yield of low- direct photons emitted from heavy ion collisions shows a common scaling behavior with that takes the form . Up to of 2 to 2.5 GeV/ both parameters and are independent of and centrality of the event sample. The parameter depends on , but does not. To extend these observations, the AuAu data at = 200 GeV and the PbPb data at 2760 GeV were analyzed at larger . It was found that does depend on even in the range from 2 to 5 GeV/ where direct-photon emission is not yet dominated by prompt-photon production. However, remains remarkably insensitive to , , and centrality.

A possible scenario, consistent with the observations, is that direct-photon radiation at low originates from thermal processes while the collision system transitions from the QGP phase to a hadron gas. This would naturally be at similar temperature and expansion velocity independent of , collision centrality, and colliding species. In the range from 2 to 5 GeV/ there might be a contribution from the QGP phase earlier in the collision which is more pronounced at higher collision energies. While the data seem qualitatively consistent with this conjecture, model calculations suggest that the dependence of the direct-photon yield should vary with , as different photon sources are expected to scale differently with and would contribute to different regions. In contrast, within the experimental uncertainties, no evidence for such a dependence of was detected.

Acknowledgements.

We thank the staff of the Collider-Accelerator and Physics Departments at Brookhaven National Laboratory and the staff of the other PHENIX participating institutions for their vital contributions. We also thank J.F. Paquet for many fruitful discussions and sharing additional information. We acknowledge support from the Office of Nuclear Physics in the Office of Science of the Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation, Abilene Christian University Research Council, Research Foundation of SUNY, and Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Vanderbilt University (U.S.A), Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Japan), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico and Funda cão de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (Brazil), Natural Science Foundation of China (People’s Republic of China), Croatian Science Foundation and Ministry of Science and Education (Croatia), Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (Czech Republic), Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Commissariat à l’Énergie Atomique, and Institut National de Physique Nucléaire et de Physique des Particules (France), J. Bolyai Research Scholarship, EFOP, the New National Excellence Program (ÚNKP), NKFIH, and OTKA (Hungary), Department of Atomic Energy and Department of Science and Technology (India), Israel Science Foundation (Israel), Basic Science Research and SRC(CENuM) Programs through NRF funded by the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Science and ICT (Korea), Physics Department, Lahore University of Management Sciences (Pakistan), Ministry of Education and Science, Russian Academy of Sciences, Federal Agency of Atomic Energy (Russia), VR and Wallenberg Foundation (Sweden), University of Zambia, the Government of the Republic of Zambia (Zambia), the U.S. Civilian Research and Development Foundation for the Independent States of the Former Soviet Union, the Hungarian American Enterprise Scholarship Fund, the US-Hungarian Fulbright Foundation, and the US-Israel Binational Science Foundation.References

- Stankus [2005] P. Stankus, Direct photon production in relativistic heavy-ion collisions, Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 55, 517 (2005).

- David et al. [2008] G. David, R. Rapp, and Z. Xu, Electromagnetic Probes at RHIC-II, Phys. Rept. 462, 176 (2008).

- Linnyk et al. [2016] O. Linnyk, E. L. Bratkovskaya, and W. Cassing, Effective QCD and transport description of dilepton and photon production in heavy-ion collisions and elementary processes, Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 87, 50 (2016).

- David [2020] G. David, Direct real photons in relativistic heavy ion collisions, Rept. Prog. Phys. 83, 046301 (2020).

- van Hees et al. [2011] H. van Hees, C. Gale, and R. Rapp, Thermal Photons and Collective Flow at the Relativistic Heavy-Ion Collider, Phys. Rev. C 84, 054906 (2011).

- van Hees et al. [2015] H. van Hees, M. He, and R. Rapp, Pseudo-critical enhancement of thermal photons in relativistic heavy-ion collisions?, Nucl. Phys. A 933, 256 (2015).

- Dion et al. [2011] M. Dion, J.-F. Paquet, B. Schenke, C. Young, S. Jeon, and C. Gale, Viscous photons in relativistic heavy ion collisions, Phys. Rev. C 84, 064901 (2011).

- Shen et al. [2014] C. Shen, U. W. Heinz, J.-F. Paquet, and C. Gale, Thermal photons as a quark-gluon plasma thermometer reexamined, Phys. Rev. C 89, 044910 (2014).

- Shen et al. [2016] C. Shen, J. F. Paquet, G. S. Denicol, S. Jeon, and C. Gale, Thermal photon radiation in high multiplicity Pb collisions at the Large Hadron Collider, Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 072301 (2016).

- Paquet et al. [2016] J.-F. Paquet, C. Shen, G. S. Denicol, M. Luzum, B. Schenke, S. Jeon, and C. Gale, Production of photons in relativistic heavy-ion collisions, Phys. Rev. C 93, 044906 (2016).

- Bratkovskaya et al. [2008] E. L. Bratkovskaya, S. M. Kiselev, and G. B. Sharkov, Direct photon production from hadronic sources in high-energy heavy-ion collisions, Phys. Rev. C 78, 034905 (2008).

- Bratkovskaya [2014] E. L. Bratkovskaya, Phenomenology of photon and dilepton production in relativistic nuclear collisions, Nucl. Phys. A 931, 194 (2014).

- Linnyk et al. [2014] O. Linnyk, W. Cassing, and E. L. Bratkovskaya, Centrality dependence of the direct photon yield and elliptic flow in heavy-ion collisions at =200 GeV, Phys. Rev. C 89, 034908 (2014).

- Chiu et al. [2013] M. Chiu, T. K. Hemmick, V. Khachatryan, A. Leonidov, J. Liao, and L. McLerran, Production of Photons and Dileptons in the Glasma, Nucl. Phys. A 900, 16 (2013).

- McLerran and Schenke [2014] L. McLerran and B. Schenke, The Glasma, Photons and the Implications of Anisotropy, Nucl. Phys. A 929, 71 (2014).

- McLerran and Schenke [2016] L. McLerran and B. Schenke, A Tale of Tails: Photon Rates and Flow in Ultra-Relativistic Heavy Ion Collisions, Nucl. Phys. A 946, 158 (2016).

- Klein-Bösing and McLerran [2014] C. Klein-Bösing and L. McLerran, Geometrical Scaling of Direct-Photon Production in Hadron Collisions from RHIC to the LHC, Phys. Lett. B 734, 282 (2014).

- Berges et al. [2017] J. Berges, K. Reygers, N. Tanji, and R. Venugopalan, Parametric estimate of the relative photon yields from the glasma and the quark-gluon plasma in heavy-ion collisions, Phys. Rev. C 95, 054904 (2017).

- Khachatryan et al. [2018] V. Khachatryan, B. Schenke, M. Chiu, A. Drees, T. K. Hemmick, and N. Novitzky, Photons from thermalizing matter in heavy ion collisions, Nucl. Phys. A 978, 123 (2018).

- Monnai [2014] A. Monnai, Thermal photon with slow quark chemical equilibration, Phys. Rev. C 90, 021901(R) (2014).

- Lee and Zahed [2014] C.-H. Lee and I. Zahed, Electromagnetic Radiation in Hot QCD Matter: Rates, Electric Conductivity, Flavor Susceptibility and Diffusion, Phys. Rev. C 90, 025204 (2014).

- Turbide et al. [2004] S. Turbide, R. Rapp, and C. Gale, Hadronic production of thermal photons, Phys. Rev. C 69, 014903 (2004).

- Dusling and Zahed [2010] K. Dusling and I. Zahed, Thermal photons from heavy ion collisions: A spectral function approach, Phys. Rev. C 82, 054909 (2010).

- Kim et al. [2017] Y.-M. Kim, C.-H. Lee, D. Teaney, and I. Zahed, Direct photon elliptic flow at energies available at the BNL Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider and the CERN Large Hadron Collider, Phys. Rev. C 96, 015201 (2017).

- Heffernan et al. [2015] M. Heffernan, P. Hohler, and R. Rapp, Universal Parametrization of Thermal Photon Rates in Hadronic Matter, Phys. Rev. C 91, 027902 (2015).

- Linnyk et al. [2015] O. Linnyk, V. Konchakovski, T. Steinert, W. Cassing, and E. L. Bratkovskaya, Hadronic and partonic sources of direct photons in relativistic heavy-ion collisions, Phys. Rev. C 92, 054914 (2015).

- Basar et al. [2012] G. Basar, D. E. Kharzeev, and V. Skokov, Conformal anomaly as a source of soft photons in heavy ion collisions, Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 202303 (2012).

- Basar et al. [2014] G. Basar, D. E. Kharzeev, and E. V. Shuryak, Magneto-sonoluminescence and its signatures in photon and dilepton production in relativistic heavy ion collisions, Phys. Rev. C 90, 014905 (2014).

- Muller et al. [2014] B. Muller, S.-Y. Wu, and D.-L. Yang, Elliptic flow from thermal photons with magnetic field in holography, Phys. Rev. D 89, 026013 (2014).

- Ayala et al. [2017] A. Ayala, P. Mercado, and C. Villavicencio, Magnetic catalysis of a finite size pion condensate, Phys. Rev. C 95, 014904 (2017).

- Adler et al. [2005] S. S. Adler et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Centrality dependence of direct photon production in GeV AuAu collisions, Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 232301 (2005).

- Aggarwal et al. [2000] M. M. Aggarwal et al. (WA98 Collaboration), Observation of direct photons in central 158-A-GeV Pb-208 + Pb-208 collisions, Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 3595 (2000).

- Aggarwal et al. [2004] M. M. Aggarwal et al. (WA98 Collaboration), Interferometry of direct photons in central Pb-208+Pb-208 collisions at 158-A-GeV, Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 022301 (2004).

- Adare et al. [2010a] A. Adare et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Enhanced production of direct photons in Au+Au collisions at =200 GeV and implications for the initial temperature, Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 132301 (2010a).

- Adare et al. [2015] A. Adare et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Centrality dependence of low-momentum direct-photon production in AuAu collisions at =200 GeV, Phys. Rev. C 91, 064904 (2015).

- Adare et al. [2012a] A. Adare et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Observation of direct-photon collective flow in =200 GeV Au+Au collisions, Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 122302 (2012a).

- Adare et al. [2016a] A. Adare et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Azimuthally anisotropic emission of low-momentum direct photons in AuAu collisions at =200 GeV, Phys. Rev. C 94, 064901 (2016a).

- Adamczyk et al. [2017a] L. Adamczyk et al. (STAR Collaboration), Direct virtual photon production in Au+Au collisions at = 200 GeV, Phys. Lett. B 770, 451 (2017a).

- Adam et al. [2016] J. Adam et al. (ALICE Collaboration), Direct photon production in Pb-Pb collisions at = 2.76 TeV, Phys. Lett. B 754, 235 (2016).

- Adare et al. [2019] A. Adare et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Beam Energy and Centrality Dependence of Direct-Photon Emission from Ultrarelativistic Heavy-Ion Collisions, Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 022301 (2019).

- Afanasiev et al. [2012] S. Afanasiev et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Measurement of Direct Photons in Au+Au Collisions at =200 GeV, Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 152302 (2012).

- Adare et al. [2013] A. Adare et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Direct photon production in Au collisions at =200 GeV, Phys. Rev. C 87, 054907 (2013).

- Adare et al. [2012b] A. Adare et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Direct-Photon Production in Collisions at GeV at Midrapidity, Phys. Rev. D 86, 072008 (2012b).

- Adler et al. [2007] S. S. Adler et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Measurement of direct photon production in collisions at , Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 012002 (2007).

- Khachatryan [2019] V. Khachatryan (PHENIX Collaboration), PHENIX measurements of low momentum direct photon radiation, Nucl. Phys. A 982, 763 (2019).

- Drees [2019] A. Drees (PHENIX Collaboration), PHENIX Measurements of Beam Energy Dependence of Direct Photon Emission, Proc. Sci. HardProbes2018, 176 (2019).

- Adare et al. [2018] A. Adare et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Low-momentum direct photon measurement in CuCu collisions at GeV, Phys. Rev. C 98, 054902 (2018).

- Adcox et al. [2003a] K. Adcox et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), PHENIX detector overview, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sec. A 499, 469 (2003a).

- Khachatryan [2017] V. Khachatryan, The Quark Gluon Plasma probed by Low Momentum Direct Photons in Au+Au Collisions at 62.4 GeV and 39 GeV beam energies, Ph.D. thesis, Stony Brook University (2017), https://inspirehep.net/literature/1804505.

- Adare et al. [2010b] A. Adare et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Detailed measurement of the pair continuum in and AuAu collisions at GeV and implications for direct-photon production, Phys. Rev. C 81, 034911 (2010b).

- Allen et al. [2003] M. Allen et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), PHENIX inner detectors, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sec. A 499, 549 (2003).

- Adcox et al. [2003b] K. Adcox et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), PHENIX central arm tracking detectors, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sec. A 499, 489 (2003b).

- Aizawa et al. [2003] M. Aizawa et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), PHENIX central arm particle ID detectors, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sec. A 499, 508 (2003).

- Aphecetche et al. [2003] L. Aphecetche et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), PHENIX calorimeter, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sec. A 499, 521 (2003).

- Anderson et al. [2011] W. Anderson et al., Design, Construction, Operation and Performance of a Hadron Blind Detector for the PHENIX Experiment, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sec. A 646, 35 (2011).

- Adare et al. [2012c] A. Adare et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Evolution of suppression in Au+Au collisions from to 200 GeV, Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 152301 (2012c), [Phys. Rev.Lett. 125, 049901(E) (2020)].

- Abelev et al. [2007] B. I. Abelev et al. (STAR Collaboration), Energy dependence of , and anti- transverse momentum spectra for AuAu collisions at and 200 GeV, Phys. Lett. B 655, 104 (2007).

- Adamczyk et al. [2017b] L. Adamczyk et al. (STAR Collaboration), Bulk Properties of the Medium Produced in Relativistic Heavy-Ion Collisions from the Beam Energy Scan Program, Phys. Rev. C 96, 044904 (2017b).

- Ren and Drees [2021] Y. Ren and A. Drees, Examination of the universal behavior of the -to- ratio in heavy-ion collisions, Phys. Rev. C 104, 054902 (2021).

- Paquet [2017] J. F. Paquet, (2017), private communication, uses nuclear PDF nCTEQ15-np and photon fragmentation function BFG-II.

- Adare et al. [2016b] A. Adare et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Transverse energy production and charged-particle multiplicity at midrapidity in various systems from to 200 GeV, Phys. Rev. C 93, 024901 (2016b).

- Zyla et al. [2020] P. A. Zyla et al. (Particle Data Group), Review of Particle Physics, Prog. Theor. and Exp. Phys. 2020, 083C01 (2020).

- Alpgard et al. [1982] K. Alpgard et al. (UA5 Collaboration), Comparison of and Interactions at GeV, Phys. Lett. B 112, 183 (1982).

- Alner et al. [1986] G. J. Alner et al. (UA5 Collaboration), Scaling of Pseudorapidity Distributions at c.m. Energies Up to 0.9 TeV, Z. Phys. C 33, 1 (1986).

- Adam et al. [2017] J. Adam et al. (ALICE Collaboration), Charged-particle multiplicities in proton-proton collisions at to 8 TeV, Eur. Phys. J. C 77, 33 (2017).

- Aamodt et al. [2011] K. Aamodt et al. (ALICE Collaboration), Centrality dependence of the charged-particle multiplicity density at mid-rapidity in Pb-Pb collisions at TeV, Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 032301 (2011).

- Paquet [2020] J. F. Paquet, (2020), private communication.

- Gale et al. [2021] C. Gale, J.-F. Paquet, B. Schenke, and C. Shen, Probing Early-Time Dynamics and Quark-Gluon Plasma Transport Properties with Photons and Hadrons, Nucl. Phys. A 1005, 121863 (2021).