My Publication Title — Multiple Authors

A Longitudinal Dataset of Twitter ISIS Users

Abstract

We present a large longitudinal dataset of tweets from two sets of users that are suspected to be affiliated with ISIS. These sets of users are identified based on a prior study and a campaign aimed at shutting down ISIS Twitter accounts. These users have engaged with known ISIS accounts at least once during 2014-2015 and are still active as of 2021. Some of them have directly supported the ISIS users and their tweets by retweeting them, and some of the users that have quoted tweets of ISIS, have uncertain connections to ISIS seed accounts. This study and the dataset represent a unique approach to analyzing ISIS data. Although much research exists on ISIS online activities, few studies have focused on individual accounts. Our approach to validating accounts as well as developing a framework for differentiating accounts’ functionality (e.g., propaganda versus operational planning) offers a foundation for future research. We perform some descriptive statistics and preliminary analyses on our collected data to provide a deeper insight and highlight the significance and practicality of such analyses. We further discuss several cross-disciplinary potential use cases and research directions.

1 Introduction

The past few years have seen social media as an effective tool for facilitating uprisings and enticing dissent in the Middle East and beyond. (Lotan et al. 2011; Starbird and Palen 2012; Berger and Morgan 2015). The embrace of social media in the Middle East has intensified the battlespace and permitted ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria111Also known as the Islamic State (IS), the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), and in Arabic, Daesh, is a militant Sunni Islamist extremist group that follows a Salafi jihadist doctrine.) and similar groups to confront existing regimes, by spreading propaganda, recruiting sympathizers, enabling and inspiring global operations and undermining rivals (Berger and Morgan 2015). The FBI describes ISIS as the most adept terrorist group at using Internet and social media propaganda to recruit new members (Office 2016). ISIS is widely recognized for its online presence, and the importance it attributes to Twitter specifically (Vidino and Hughes 2015). With the decline of the physical caliphate, ISIS increasingly has begun to rely upon “virtual entrepreneurs” (Meleagrou-Hitchens and Hughes 2017), “fanboy” (Darwish 2019) and a sophisticated online media operation to propagate its goals.

Prior research efforts have attempted to capture a glimpse of these online activities, in order to investigate ISIS online recruiting and campaigning efforts. However, to date, we are aware of very few datasets of known extremists’ online activities (Tribe 2015; Alfifi et al. 2018). Of these, only a small sample is available for research (Tribe 2015).

Importantly, existing datasets refer to online activities before 2015 which is a watershed time period. In 2015, ISIS online media efforts faced a crackdown by technology companies anxious to remove content and suspend users’ accounts. ISIS had to change its online strategy. Very little is known about ISIS online whereabouts since then. Although most suspicious Twitter accounts are suspended or removed by now, ISIS physical caliphate has collapsed, its leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, is dead, their sympathizers and supporters are still active across a spectrum of social media applications such as WhatsApp, Telegram, and TamTam (Amarasingam 2020). Notwithstanding this transition, Twitter still provides the largest community and potential audience for ISIS supporters and a considerable number of ISIS supporters are still active on Twitter.

In this paper, we present a large longitudinal dataset of tweets from two sets of users that are suspected to be affiliated with ISIS, referred to as ISIS2015-21. Our collected dataset includes almost 10 million tweets of 6,173 accounts linked to ISIS and its propaganda (1,614 tweets per account on average). Importantly, these accounts’ activities span from 2009 to 2021, therefore offering a longitudinal perspective to extremists online traces. We have found evidence of real correlations between these sympathizers and ISIS, some of which are suspended, removed, or reported as suspicious ISIS-related accounts since 2015.

Our approach to validating accounts as well as developing a framework for differentiating accounts’ functionality (e.g., propaganda versus operational planning) results in a high quality dataset with unique longitudinal properties, that can serve as foundation for future research across multiple disciplines. We perform some descriptive statistics and preliminary analyses on our collected data to provide a deeper insight and highlight the significance and practicality of such analyses. We further discuss several cross-disciplinary potential use cases and research directions.

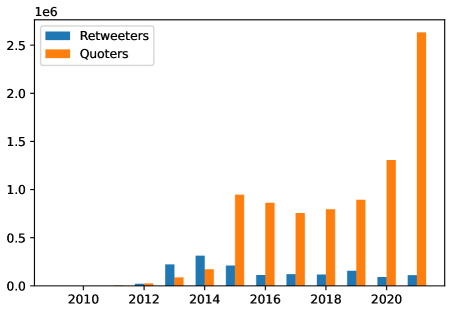

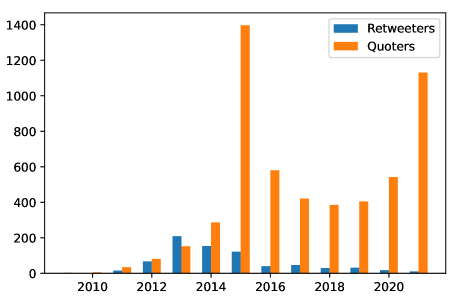

2 Data Collection

This section reports on the temporal span and volume of the collected data, as well as analyses estimating its generalizable value. We used the official Twitter’s API for User Tweet Timeline222https://developer.twitter.com/en/docs/twitter-api/tweets/timelines/introduction to collect timelines from a specific set of users that are discussed below. The API enables collection of the most recent 3,200 tweets (including original tweets, retweets, replies, and quotes) that can be found on users’ timelines. Collection from the timeline is limited to the most 3,200 tweets; thus, if a user has less than 3,200 tweets (all types combined) the whole timeline may be collected but if the combined tweets exceeds 3,200 only the most 3,200 are collected. All tweets were collected during December 6–7, 2021 but depending on the account activities, they might include tweets from as early as 2009. For users that have more than 3,200 tweets in their timelines, most of the collected tweets belong to 2021 (see Figure 1).

| Group | Accounts | Suspended | Removed | Alive | Private | Public | Cleaned | Target | CtrlSec | Tweets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retweeters | 1,000 | 25 | 136 | 839 | 88 | 751 | 4 | 747 | 1+ | 1,480,919 |

| Quoters | 16,672 | 9,290 | 1,459 | 5,923 | 466 | 5,457 | 31 | 5,426 | 27+ | 8,483,234 |

| Grand Total | 17,672 | 9,315 | 1,595 | 6,762 | 554 | 6,208 | 35 | 6,173 | 28+ | 9,964,153 |

Accounts description

We used an account-driven approach to generate our tweet repository and collected about 10 million tweets generated by 6,173 accounts during the timeline from April 2009 to December 2021 (see Figure 1 for accounts’ activities). We identified ISIS-related accounts from a Twitter repository (referred to as Alfifi dataset in what follows) originally collected by researchers during the 2014–2015 time frame (Alfifi et al. 2018). In the study, authors identified potential ISIS-related accounts through a target crowd-sourced effort, and later studied them to detect the markers of actual ISIS users. This crowd-sourcing effort was a campaign originally initiated by a faction of the Anonymous hacking group333https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anonymous_(hacker_group) called Controlling Section444As of 2021, four Twitter users with similar usernames of @CtrlSec (https://twitter.com/CtrlSec), @CtrlSec0, @CtrlSec1, and @CtrlSec2 are directly associated to this campaign. (Brooking 2015) in 2015 that invited Arabic speakers to report Twitter accounts presumed associated with ISIS after several fatal ISIS attacks (Hern 2015). This faction has been in charge of taking down ISIS-related websites, exposing their Twitter accounts, stealing their bitcoins, and doxing their recruiters (Brooking 2015). The campaign is still active and exposes new suspicious and likely ISIS affiliates.

The original Alfifi’s dataset included not only tweets from presumed ISIS accounts, but also tweets and account information about Retweeters of ISIS—accounts that had retweeted ISIS tweets—and Quoters of ISIS—users that had quoted tweets posted by the known ISIS seed accounts at least once. In 2021, we launched a tweet collection of alive (neither suspended nor removed) and public accounts (their tweets are not protected) to collect timelines of these original accounts, so as to develop a new dataset reflecting the recent activities of potential ISIS sympathizers and ISIS affiliates that were active and engaging with known ISIS seed accounts in 2014–2015. We observed that other than the aforementioned ISIS seed accounts that were identified and suspended by Twitter around 2014–2015, the majority of Twitter accounts in the Alfifi’s dataset are no longer accessible and have been either suspended or removed since then. Some of these suspensions can be results of the Controlling Section’s campaign, because they post suspicious user accounts and ask users to report them, so that Twitter suspends the identified malicious users.

In total, as reported in Table 1, we identified 17,672 user IDs from both Retweeters and Quoters. Of this users’ base, 9,315 users were suspended and 1,595 users have removed their accounts since 2014–2015 and are not included. Our data also does not include tweets from a number of users that have protected their accounts since 2014–2015. 88 users out of the total 839 alive Retweeters of ISIS, and 466 users out of the total of 5,923 Quoters of ISIS that have made their profiles private. Therefore, only 6,208 accounts out of the initial 17,672 accounts were neither suspended nor removed and had public profiles at the time of our tweet collection. Additionally, 35 users had removed all the tweets from their timelines and we discarded them in our tweet collection.

Out of the remaining 6,173 users, we were able to collect activities (i.e., up to 3,200 most recent tweets) of 4,835 users. For the remaining 1,338 Quoters, we were only able to collect up to the 100 most recent tweets per user. This is because this API returns tweets from a user’s timeline in a pagination mode, each page containing up to 100 tweets.555Even if a user has over 100 tweets in their timeline, we observed that the API may return less than 100 tweets in the first page. Note that we had already collected one page of tweets from all the 6,173 users before hitting the API’s limit.666We initially collected one page of tweets (up to 100 tweets) from each user and then iterated through all of them to collect the rest of their timelines.Therefore, we collected more than 3,200 tweets for 25 Retweeters and 442 Quoters.

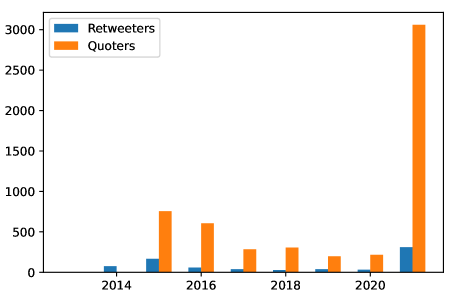

Figure 2 shows the oldest and earliest tweets that we have from these users. As it can be seen, there are two spikes in 2015 and 2021. The latter indicates that a large number of users have many tweets and have been recently active, so by collecting 3,200 tweets, we have not dug deep into their historical tweets. But, the former and our manual inspection of users shows that a considerable number of these users have been created or started their activities around the 2015 time frame when many of ISIS attacks happened.

We have also investigated dormant accounts—accounts that have become inactive after a specific time—and have illustrated them in Figure 3. As it can be observed, a considerable number of users have stayed dormant since 2015–2016—around the time the Alfifi dataset was collected and several fatal ISIS attacks had occurred.

Overall, we collected 9,840,206 tweets, from 4,835 accounts, including all the alive Retweeters with public profiles and 4,088 Quoters during the 2009–2021 time frame. Additionally, we had collected 123,947 tweets from the remaining 1,338 Quoters, which increased our total number of tweets to 9,964,153. None of the original ISIS accounts identified by Alififi (Alfifi et al. 2018) was found alive in December 2021. Furthermore, out of 4,835 users for whom we collected the whole timelines, two Retweeters and 403 Quoters had less than 3,200 historical tweets in their timelines and the rest of accounts had more activities.

In Table 1, we also report data for the Cleaned accounts, i.e. accounts that have deleted all the tweets from their timelines. We have discarded the cleaned accounts from our final number of users that are shown in the “Target” column.

Accounts’ validation

The tweets in our dataset are likely from ISIS sympathizers, but the degree of their involvement is not certain. Retweeting can be considered as an act of support and help for spreading a message to a larger audience. It has been shown (Alfifi et al. 2018) that retweeters of ISIS are more likely to engage in malicious activities. Additionally, we may observe quotes of other tweets when someone tries to either support or oppose an ISIS-related message or user. In addition to the previous suspicious activities and potential connections to ISIS that we have observed from these users in the old dataset, we have looked up their user IDs in the Controlling Section’s target suspicious accounts that is a more recent list of potentially ISIS-related users.

It is extremely challenging to fully ascertain an account’s origin and its actual affiliation. Yet, we have strong indicators that our dataset includes several accounts are not only ISIS-related but most likely, are from ISIS. We found some overlap among the accounts we collected and the accounts reported as ISIS (see Table 1), under the “CtrlSec” column. This highlights that while some of these suspicious accounts could have been identified and suspended around the time that Alfili’s paper was published, they were not shut down by Twitter yet and had remained alive for a while. We also observed three new suspensions and 13 users that removed their accounts during our two-day data collection which is indicative of the suspicious nature of our target users.

| Group | Original Tweet | Retweet | Quote | Reply | Quote & Reply |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retweeters | 765,128 | 513,087 | 10,677 | 192,375 | 348 |

| Quoters | 2,176,986 | 3,678,238 | 443,657 | 2,200,187 | 15,834 |

| Group | Top Hashtags | Count | Total Hashtags | Top Keywords | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tweet in remembrance of Allah* | 97,492 | Allah* | 340,281 | ||

| muslim’s treasure* | 43,971 | o Allah* | 245,484 | ||

| prayer to my lord* | 27,494 | martyred* | 74,663 | ||

| Quran | 19,195 | said* | 49,564 | ||

| Retweeters | hadith | 16,899 | 599,121 | face with tears of joy emoji | 41,812 |

| Allah | 8,484 | god* | 38,359 | ||

| publish his biography* | 6,298 | peace be upon him* | 38,352 | ||

| Saudi Arabia* | 4,511 | lord* | 33,822 | ||

| tweet hadith* | 4,269 | peace* | 32,266 | ||

| crescent moon* | 3,241 | day* | 31,973 | ||

| Saudi Arabia* | 53,477 | Allah* | 1,312,104 | ||

| Iraq* | 37,011 | face with tears of joy emoji | 534,122 | ||

| Syria* | 36,063 | o Allah* | 404,598 | ||

| Immediate* | 28,631 | said* | 178,785 | ||

| Quoters | Iran* | 26,680 | 3211867 | today* | 171,952 |

| Turkey* | 25,161 | swear to Allah* | 152,045 | ||

| Qatar* | 23,239 | white heart emoji | 144,907 | ||

| Yeman* | 21,329 | Muhammad* | 136,848 | ||

| Egypt* | 21,218 | the people* | 130592 | ||

| Quran | 16,580 | day* | 128,641 |

| Language | # Tweets |

|---|---|

| Arabic | 1,384,028 |

| Undefined | 51,645 |

| English | 37,625 |

| Indonesian | 2,057 |

| Spanish | 491 |

| Korean | 486 |

| Catalan | 424 |

| Persian | 369 |

| French | 350 |

| Tagalog | 341 |

| Other | 3,103 |

| Language | # Tweets |

|---|---|

| Arabic | 7,632,693 |

| Undefined | 482,756 |

| English | 297,003 |

| French | 18,819 |

| Persian | 9,460 |

| Indonesian | 6,926 |

| Turkish | 6,205 |

| Spanish | 4,780 |

| Hebrew | 3,252 |

| Catalan | 3,090 |

| Other | 18,250 |

3 Data Sharing and Format

Our ISIS2015-21 dataset is available for download under FAIR principles (Wilkinson et al. 2016) in CSV and ZIP formats. The data includes two tables for retweeters and quoters, and tweets are keyed by Twitter assigned IDs and augmented with additional metadata as described below. Moreover, the data includes unique keys for different types of media that appeared in the tweets, including photos, videos, and animated GIFs, as well as aggregated tables for the websites and URL domains appeared in the tweets of each the two groups along with their corresponding frequencies.

The ISIS2015-21 dataset conforms with FAIR principles.777https://www.force11.org/group/fairgroup/fairprinciples The dataset is Findable as it is publicly available on Harvard Dataverse. It is also Accessible because it can be accessed by anyone around the world. The original dataset is in CSV format, and contains all the tweet IDs that can be utilized to lookup or download the tweets, therefore it is Interoperable. We release all the tweet IDs and user IDs in our dataset with descriptions detailed in this paper making the dataset Reusable to the research community.

The dataset also includes a list of user IDs of suspended and removed accounts, for potential archival research. These tables do not include raw tweet data beyond the ID, according to Twitter’s Terms of Service. However, to support use of the data without being required to download (“hydrate”) the full set of tweets, we augment the Tweets table with several key properties. For each tweet we provide the author’s ID, the conversion ID that the tweet belongs to, the timestamp for the tweet, the number of total retweets, replies, quotes, and likes as computed by Twitter. The Tweets table properties also include the language of the tweet as identified by Twitter, whether the tweet contain sensitive and Not-Suitable-For-Work (NSFW) content, the source or the app used to post the tweet, and the IDs of the retweeted, replied, or quoted tweets where they apply (ID of zero elsewhere).

4 Use Cases

The primary motivation in creation of this dataset is to study ISIS’s evolving presence on social media in the last 10 years. Following is a series of use cases that permit the analysis of ISIS methods for disseminating propaganda or the ”tools of the trade”; improving message longevity and amplification increasing the possibility of resonance within target populations, and ultimately creating the link between the individual and group. We also provide use cases with a non-ISIS focus such as studying conversations and hate speech. Note that this list is not exhaustive.

4.1 Language and Network Analysis

An expected contribution to this dataset is to foster researchers’ understanding of language and network patterns of extremists online. Data-driven studies in this space have highlighted some interesting findings so far, such as the limited social network reach of ISIS sympathizers and a self-reinforced network of users (Berger and Morgan 2015). Yet, several of these findings have not been validated on online activities post 2015 in the wake of tech companies crackdown and the disintegration of physical caliphate which provided some resources to the media operations. We anticipate that in light of these events and the new attentive eye of Twitter toward extremists’ activities, ISIS members and sympathizers have morphed their online behavior to evade detection and yet still spread new messages of relevance to them. This new dataset can be used to extract recent online patterns of behavior, online signatures, and online resilience. Furthermore, one could examine the evolution of both “successful” and “unsuccessful” ISIS sympathizers in our dataset, to identify the impact of existing interventions already present the dataset.

The new Twitter’s API (API v.2) also identifies and provides a set of annotations for each tweet containing some of its named entities such as Person names, Places, Organizations, Products, and Others that do not fill into these categories.888https://developer.twitter.com/en/docs/twitter-api/annotations/overview Table 5 illustrates the frequency of each of these named entities in our dataset as well as the number of hashtags for each group of users.

| Group | Person | Place | Organization | Product | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retweeters | 119,756 | 78,662 | 33,093 | 7,670 | 3,259 |

| Quoters | 1,040,521 | 1,508,607 | 265,898 | 56,554 | 10,506 |

As this metamorphosis evolves, we see potential in investigating individual-level models of influence in domains where information sharing is driven by political and extremist agenda and the receiving population may be highly heterogeneous. One approach might be to focus on creating a network-based behavioral model, as well as an individual-level model that can capture imitative behaviors. This analysis builds on earlier insights into how extremists imitate each other through songs, martyr posters, and pledges of allegiance.One tool for analysis is the study of discourse-level contagiousness that drives extremism to uncover overall patterns of extremist ideology infectiousness. ISIS uses multiple platforms and information tools to promote its cause, influence behavior, and conduct operational business. The process is easy to understand. Create the desired message and disseminate it to either a targeted or broad audience depending upon the goal. The objective is to have the message “stick” or shape a conversation around a topic thus influencing thought and/or behavior.

More specifically, contagious online discourses consist of a series of online messages that agree with the others in certain subjectivity dimensions, such as sentiment polarity (e.g., unanimously positive or negative) or emotion types (e.g., full of anger), or in writing styles (e.g., exaggeration using similes, slang, or punctuation). Negative online contents are often inflammatory or extremely emotional. We can envision using sentiment and emotion analysis methods such as lexicon based sentiment classification (Jurek, Mulvenna, and Bi 2015), to develop tools to analyze rich extra-propositional properties of user generated texts in order to facilitate modeling contagiousness of online discourses.

4.2 Analysis of ISIS Propaganda

Beyond contagion, we can investigate propaganda messages in our dataset. A propaganda campaign is a combination of formal structure and bottom-up information dissemination coordinated by the Diwan of Central Media. ISIS’s presence combines the formal “news agency,” AMAQ, with direct messaging applications (e.g., Twitter, Telegram, or YouTube), and a Dark Web presence. Understanding the overall media structure is helpful. However, this structure introduces a challenge in that each of these environments may be used for multiple tasks complicating the identification of relevant propaganda pieces. Thus, a relevant analytic model needs a data fusion approach. For the purposes of this study which focuses exclusively on Twitter, three processes provide a basis:

-

•

Identify relevant propaganda pieces by understanding that propaganda and operational content differ,

-

•

Recognize indicators of message distribution aimed at increasing sharing which reflects propaganda,

-

•

Explore message content in terms of accuracy, media used and language.

According to the US government, terrorist propaganda provides pervasive and continuous condemnation of the “other side,” and proposes ideological alternatives which they know would not be generally acceptable if they were openly revealed (of Chiefs of Police et al. 1975). Two components from this definition help to broadly identify a method for understanding terrorist propaganda and can be instrumental for detection and analysis in our dataset. To be “pervasive and continuous” message sharing is critical. Whereas an operational message has a specific audience, a propaganda message demands broad dissemination. Thus, through information and network analysis, messages in which (1) the creator has few followers but (2) whose message is widely disseminated via retweets among a larger network likely indicates propaganda. For instance, we identified a relatively highly disseminated tweet999The IDs of the tweet and the user were 1182737917120307201 and 965077656 respectively. stating religious content that only had 108 followers at the time of data collection, but the tweet had gained 305 retweets, 327 likes, and 18 replies, which are clearly indicative of propaganda.

Second, propaganda is seeded with visceral and ideological based verbiage and images. These become important in identifying something as propaganda. Whereas, operational messages deal with targeting, methods, and timing and might include images (e.g., an aerial picture of a targeted building) that have tactical importance, the language and images in propaganda messages seek to elicit an emotional response. For example, ISIS re-published the photo in Figure 4, originally published in The Guardian, with an article citing the consequences of leaving the caliphate in its English-language magazine, Dabiq (Smith 2015).

A third indicator of ISIS propaganda is the presence of hashtags. In an effort to enhance the echo chamber to which social media users gravitate, ISIS organized a sophisticated hashtag campaign. They recruited people to retweet hashtags to create trending ideas, hijack trending hashtags, curate group messaging to improve branding, and ensure message longevity even if the original platform removes it (Darwish 2019). Table 3 lists some of most frequent hashtags that are mostly about strong religious references amongst the retweeters, and amongst the quoters, most of them are clearly referring to middle-east countries. Manual inspection shows that many of hashtags with middle-east country references are news-related.

4.3 Governance and Content Moderation Monitoring

Although Twitter abrogates some responsibility for “sensitive” content to its users, asking them to self-select, it has established policies around graphic violence, adult content, and hateful imagery.101010https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/media-policy Violations may be reported by Twitter users for review or identified by Twitter’s algorithm. If determined offensive, Twitter takes enforcement actions either on a specific piece of content (e.g., an individual Tweet or Direct Message) or on an account if continuous violations are identified. It may also employ a combination of these options if the behavior violates the Twitter Rules.111111https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/enforcement-options Notwithstanding, controversy exists regarding the effectiveness of the algorithm and the extent to which it is used.121212https://www.quora.com/Does-Twitter-allow-adult-content Within the terrorism environment, some things such as a video of a beheading are easily identified and removed. Additionally accounts associated with terrorist organizations or individuals may be suspended (Berger 2018; Office 2016). We saw this occurs within the current dataset. However, some content evades the algorithm and may not be recognized as terrorism propaganda by users and thus continues of exist. Furthermore, user adaptability, persistence, and technical skills in hyperlinking content continue to circumvent controls.

4.4 ISIS Media and Redirection Strategies

As previously noted, ISIS has a diverse online media network that facilitates the dissemination of information through multiple methods and forms of content with varying sophistication. Additionally, ISIS has become masterful at redirecting users to both enhance operational security and improve message longevity. Pictures, posters, memes, and language are all tools of the ISIS propaganda machine. In December 2021, a new ISIS group, I’lami Muragham, posted four posters on Telegram proclaiming an ISIS jihad to the “last day” and encouraging resistance (MEMRI 2021b). The poster in Figure 5, entitled, “We Will Come To You From Where You Do Not Expect,” is aimed at establishing fear for the enemy while inspiring action. The message is a quote from ISIS spokesman, Al-Shaykh Al-Muhajir.

A second poster in the same release contained a quote by the dead leader al-Baghdadi. As a result, research into developing processes for identifying the presence of posters along with a quotation from a leader process may help classify messages as propaganda.

ISIS’ media strategy shows its sophistication by reiterating messaging and adaptability to increase messaging longevity. The former is accomplished through message re-enforcement, for example, repeating messages in various environments. A poster distributed via Telegram references a quotation from a specific issue of al Naba, ISIS’ weekly newspaper. As a result, the messages are mutually reinforcing as well as offering the receiver links to other forms of propaganda that further promulgate the echo chamber increasing the likelihood resonance. Another strategy are adaptable measures meant to protect communications. Previous research contends that tabulating suspended accounts as a measure of counter-terrorism policy is incomplete and deceiving (Weirman and Alexander 2020). This is significant for the research on propaganda because it indicates that the suspension of accounts does not eliminate the propaganda. Strategies include active measures to preserve communications when accounts are suspended and to re-direct users to newly created accounts or a return to a particular platform.

An active measure to insulate networks is through file-sharing of URLs (Ibid). In our dataset, we have identified a large set of URLs and media content that should be analyzed. The presence of URLs or truncated URLs may well be indicative of propaganda but also provide a mechanism to further exploit the information’s path in an effort to suspend future versions of the message. In Table 7 we report some examples of URL domains that we found in our dataset. As shown, several of these URLs are related to other potential propaganda outlets (e.g., YouTube) and religious websites (e.g., “tweet4allah.com”).

| Group | Image | Video | GIF | URL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retweeters | 121,788 | 32,007 | 3,485 | 289,180 |

| Quoters | 999,985 | 317,134 | 24,738 | 2,140,794 |

| Retweeters | Quoters |

|---|---|

| du3a.org | du3a.org |

| knz.tv | youtu.be |

| tweet4allah.com | fb.me |

| gharedly.com | d3waapp.org |

| quran.ksu.edu.sa | www.facebook.com |

| knz.so | ghared.com |

| d3waapp.org | quran.to |

| 3waji.com | www.youtube.com |

| knzmuslim.com | bit.ly |

| ghared.com | ln.is |

| Retweeters | Quoters |

|---|---|

| Twitter for iPhone | Twitter for iPhone |

| Twitter for Android | Twitter for Android |

| Muslim Treasure* | Twitter Web Client |

| Quranic App* | Twitter Web App |

| Quran Tweets* | Twitter for iPad |

| GharedlyCom | |

| Twitter for BlackBerry® | Quranic App* |

| Twitter for iPad | Quran Tweets* |

| Twitter Web Client | Verse App* |

| Ayat | Tweetbot for iOS |

4.5 Data-Informed Terrorism Studies

Political terrorism relies on information operations to amplify an incident, create fear beyond the event itself, establish the group’s unity, identity, and ideological foundation creating an “ingroup” versus “outgroup” dynamic (Berger 2018) and/or provide operational direction. Within this environment, propaganda fills a vacuum created by the lack of power. It may take the form of being event-driven seeking to exploit the incident by having it trend among a broad audience or more formally it is the release of information via high quality videos, magazines, or newsletters.

ISIS and its affiliates (e.g., Islamic State – Khorasan Province (ISIS-K, IS-K or IS-KP)) have a specific process for achieving their goals. First, they seek to promote chaos both physically and virtually to demonstrate the inability of an existing entity to protect its people. From a propaganda perspective this might include videos, pictures, and comments promoting activities (i.e., violence) to demonstrate ineffectiveness. Second, as previously discussed, it seeks contagion to draw others to the cause.

A recent post on ISIS-operated Rocket.Chat encourages long-wolfs in the West provides an example of the latter: “Attack the citizens of crusader coalition countries with your knives, run them over in the streets, detonate bombs on them, and spray them with bullets. Those who preceded you on this path, who frightened the Crusaders and robbed them of safety and security in their own homes, like their deeds, may Allah accept them and replicate them …” (MEMRI 2021a).

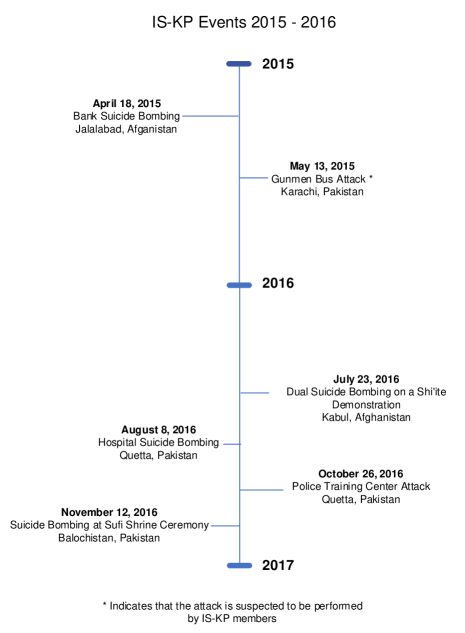

Operationally, ISIS22015-2021 dataset can be used to analyze the online activity (e.g. messaging, comments, and propaganda posts) surrounding successful real world acts of terrorism from of IS-K and its affiliates. Such activity is important both from a validation and analytic perspective. Evaluating messaging linked to real world events further strengthens the identification of propaganda and perhaps even allows a categorization of types or levels of propaganda. By comparing and contrasting Twitter commentary with reliable sources, such as multiple press comments surrounding an event, a presumption of a tweet being propaganda may be made and even measured based upon the amount of true versus fabricated information presented. This process requires further refinement.

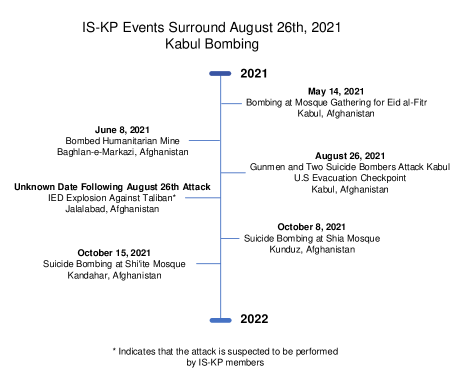

Since terrorism’s goal is to establish fear, a terrorist group can use online activity to connect their beliefs and propaganda by exploiting a successful terrorist attacks and media attention. The timelines in Figure 6 and Figure 7 show IS-K events, which have the potential to coincide with an increase in online activity of terrorist groups. As it was shown in Figure 2, the first activity of many quoters in our dataset goes back to 2015, when IS-K was formed.131313https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/islamic-state-khorasan-province We have also searched for the presence of a set of keywords related to the attacks depicted in the timeline of Figure 7. The frequency of each of these keywords for each of the two groups of users are reported in Table 9. Further analysis can study the contexts of these keywords within tweets and uncover their correlations with IS-K attacks.

The online activity (reflected in ISIS2015-21) will likely be localized to the region most impacted by the attack. It can be speculated that online activity from international regions about an attack indicates a higher severity. The large audience generated by international communications will allow for a wider spread of propaganda and benefit the basic terrorism goal of contagion to attract new members. Traces of ISIS2015-21 can be instrumental to the analysis of such propaganda. In particular, accounts means and frequency of communication provide information about a terrorist group’s developmental stage. For example, a two-level propaganda strategy in which a broad-based of popular support is built from which to inspire violent attacks is typical of more mature terrorist organizations. In addition, internal propaganda (written only for members of the terrorist group) presages the external propaganda written for the public and provides guidelines on the part violence is to play (of Chiefs of Police et al. 1975). Furthermore, the messaging process reflects maturity as well. Continuous messaging requires sustainability in terms of new content, message longevity, ad platform resilience which is difficult to achieve without a robust structure.

| Keyword | Retweeters | Quoters |

|---|---|---|

| mosque | 4,989 | 36,881 |

| al-fitr | 3,095 | 15,151 |

| bomb | 633 | 9,541 |

| gun | 423 | 4,653 |

| suicide | 316 | 5,204 |

| taliban | 257 | 17,462 |

| kabul | 61 | 2,240 |

| kandahar | 10 | 489 |

| jalalabad | 1 | 46 |

| kunduz | 1 | 30 |

| baghlan | 0 | 107 |

4.6 Beyond the Data: Nudging Anti-Normative Behavior

In addition to exploratory research, this dataset can be used as a seed to design and validate new interventions lessening the impact of extremist group influence. Upon examining the evolution of ISIS sympathizers in our dataset, we may identify the impact of existing interventions already present in the dataset (e.g., account suspension or tweet removal), and then design new anti-normative nudges based on generative language models that are informed by learned models of extremist influence. While there is evidence that networks and beliefs collectively evolve (Lazer et al. 2010), interventions designed to shape this evolution must be carefully designed to avoid unintended effects (Bail et al. 2018; Nyhan and Reifler 2010). For example, an anti-ISIS message inserted into the network to maximize exposure to ISIS sympathizers could backfire, instead strengthening the ISIS support of the sympathizers. Accordingly, carefully designed solutions must be engineered for effective anti-normative mechanisms, building on recent advances in deep learning for generating natural language (Bowman et al. 2015; Young et al. 2017).

5 Limitations

Our proposed ISIS20215-21 dataset is innovative and unique in its kind, due to the specific sub-population it accurately targets and its evident longitudinal properties. Given how accounts were originally selected and their validation obtained through manual inspection and cross-correlation with CtrlSec data, we are confident about the authenticity of the accounts and their relevance for online extremist research. Nevertheless, our dataset suffers from some limitations that should be aware to researchers interested in the data’s future use. First, due to the existing limitation in Twitter’s API, we cannot collect the complete history of each account. This however, still allows us to include tweets for many accounts that span few years of online presence (see Figure 2).

Second, even though the dataset offers a good excerpt of ISIS’ evolution, there is a growing evidence that ISIS may have moved away or shifted from Twitter for most of its online activities (Amarasingam 2020). Accordingly, while we can get a look at sympathizers and their messages, we may be missing a significant portion of their online presence and activities. Related, we suspect that there may be other accounts, that we do not include in our dataset, that are close to ISIS. We are also unable to potentially remove noisy tweets, irrelevant to our study. However, results of our preliminary analysis on the data strongly suggest that our collected content is relatively clean, and will constitute a strong seed for researchers in this space.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we present a new public dataset tracking tweets from two sets of users that are suspected to be ISIS affiliates. These users are identified based on a prior study and a campaign aimed at shutting down ISIS Twitter accounts. This study and the dataset represent a unique approach to analyze ISIS data. Although some research exists on ISIS online activities, few studies have focused on individual accounts.

The long-term aim of this project is to tackle the ambitious challenge of linking social media observations directly to online political extremism. We hope that researchers will be able to leverage the ISIS2015-2021 dataset to obtain a clearer understanding of how ISIS sympathizers use these platforms for message spreading and propaganda, especially in the recent years and with the advent of ISIS-K. The dataset can also be used as a benchmark to investigate online strategies originating from extremist groups that are not ISIS related. In turn, such insight might enable social network providers but also policy makers toward new interventions lessening the impact of extremist group influence.

7 Ethical Considerations

The dataset only collects data that is public and from alive accounts. Private accounts’ tweet IDs and data are not included. Tweets limitations imposed by Twitter’s API and ToS are respected. We have also removed all the tweet texts, full URLs, user account details, and only provide aggregated statistics, URL domains, and media keys that are not directly connected to any specific user or tweet and can be used for aggregate analysis to download the original tweets as long as they are available to the public.

References

- Alfifi et al. (2018) Alfifi, M.; Kaghazgaran, P.; Caverlee, J.; and Morstatter, F. 2018. Measuring the impact of ISIS social media strategy. MIS2. Marina Del Ray, California .

- Amarasingam (2020) Amarasingam, A. 2020. Telegram Deplatforming ISIS Has Given Them Something to Fight for. https://www.voxpol.eu/telegram-deplatforming-isis-has-given-them-something-to-fight-for. [Online; accessed 9-January-2022].

- Bail et al. (2018) Bail, C. A.; Argyle, L. P.; Brown, T. W.; Bumpus, J. P.; Chen, H.; Hunzaker, M. B. F.; Lee, J.; Mann, M.; Merhout, F.; and Volfovsky, A. 2018. Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(37): 9216–9221. ISSN 0027-8424. doi:10.1073/pnas.1804840115. URL http://www.pnas.org/content/115/37/9216.

- Berger (2018) Berger, J. M. 2018. Extremism. MIT Press.

- Berger and Morgan (2015) Berger, J. M.; and Morgan, J. 2015. The ISIS Twitter Census: Defining and describing the population of ISIS supporters on Twitter. The Brookings Project on US Relations with the Islamic World 3(20): 1–4, 25–29.

- Bowman et al. (2015) Bowman, S. R.; Vilnis, L.; Vinyals, O.; Dai, A. M.; Józefowicz, R.; and Bengio, S. 2015. Generating Sentences from a Continuous Space. CoRR abs/1511.06349. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1511.06349.

- Brooking (2015) Brooking, E. T. 2015. Anonymous vs. The Islamic State. https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/11/13/anonymous-hackers-islamic-state-isis-chan-online-war. [Online; accessed 10-January-2022].

- Darwish (2019) Darwish, M. A. 2019. From Telegram to Twitter: The Lifecycle of Daesh Propaganda Material. https://www.voxpol.eu/from-telegram-to-twitter-the-lifecycle-of-daesh-propaganda-material. [Online; accessed 13-January-2022].

- Hern (2015) Hern, A. 2015. Anonymous ’at war’ with Isis, hacktivist group confirms. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/nov/17/anonymous-war-isis-hacktivist-group-confirms. [Online; accessed 10-January-2022].

- Jurek, Mulvenna, and Bi (2015) Jurek, A.; Mulvenna, M. D.; and Bi, Y. 2015. Improved lexicon-based sentiment analysis for social media analytics. Security Informatics 4(1): 1–13.

- Lazer et al. (2010) Lazer, D.; Rubineau, B.; Chetkovich, C.; Katz, N.; and Neblo, M. 2010. The coevolution of networks and political attitudes. Political communication 27(3): 248–274.

- Lotan et al. (2011) Lotan, G.; Graeff, E.; Ananny, M.; Gaffney, D.; Pearce, I.; et al. 2011. The Arab Spring— the revolutions were tweeted: Information flows during the 2011 Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. International journal of communication 5: 31.

- Meleagrou-Hitchens and Hughes (2017) Meleagrou-Hitchens, A.; and Hughes, S. 2017. The Threat to the United States from the Islamic State’s Virtual Entrepreneurs. CTC Sentinel 10(3).

- MEMRI (2021a) MEMRI. 2021a. Jihadis Appropriate Christmas Imagery To Threaten Violence During Holiday Season. https://www.memri.org/jttm/jihadis-appropriate-christmas-imagery-threaten-violence-during-holiday-season. [Online; accessed 27-December-2021].

- MEMRI (2021b) MEMRI. 2021b. New Pro-ISIS Media Group Urges ISIS Fighters To Stand Firm In Face Of U.S. Airstrikes, Calls On Muslims In Sudan To Wage Jihad, Establish Rule Of Shari’a. https://www.memri.org/jttm/new-pro-isis-media-group-urges-isis-fighters-stand-firm-face-us-airstrikes-calls-muslims-sudan. [Online; accessed 11-December-2021].

- Nyhan and Reifler (2010) Nyhan, B.; and Reifler, J. 2010. When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior 32(2): 303–330.

- of Chiefs of Police et al. (1975) of Chiefs of Police, I. A.; of Operations, B.; Research; and of America, U. S. 1975. Clandestine Tactics and Technology-A Technical and Background Intelligence Data Service, Volume 3 .

- Office (2016) Office, G. P. 2016. ISIS Online: Countering Terrorist Radicalization and Recruitment on the Internet and Social Media. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-114shrg22476/content-detail.html. [Online; accessed 9-January-2022].

- Smith (2015) Smith, H. 2015. Shocking images of drowned Syrian boy show tragic plight of refugees. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/02/shocking-image-of-drowned-syrian-boy-shows-tragic-plight-of-refugees. [Online; accessed 26-December-2021].

- Starbird and Palen (2012) Starbird, K.; and Palen, L. 2012. (How) will the revolution be retweeted?: information diffusion and the 2011 Egyptian uprising. In Proceedings of the acm 2012 conference on computer supported cooperative work, 7–16. ACM.

- Tribe (2015) Tribe, F. 2015. How ISIS Uses Twitter. https://www.kaggle.com/fifthtribe/how-isis-uses-twitter. [Online; accessed 9-January-2022].

- Vidino and Hughes (2015) Vidino, L.; and Hughes, S. 2015. ISIS in America: From Retweets to Raqqa (George Washington University: Program on Extremism, 2015) 7.

- Weirman and Alexander (2020) Weirman, S.; and Alexander, A. 2020. Hyperlinked sympathizers: URLs and the Islamic state. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 43(3): 239–257.

- Wilkinson et al. (2016) Wilkinson, M. D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I. J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.-W.; da Silva Santos, L. B.; Bourne, P. E.; et al. 2016. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific data 3(1): 1–9.

- Young et al. (2017) Young, T.; Hazarika, D.; Poria, S.; and Cambria, E. 2017. Recent Trends in Deep Learning Based Natural Language Processing. CoRR abs/1708.02709. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1708.02709.