Optomechanics with a position-modulated Kerr-type nonlinear coupling

Abstract

Cavity optomechanics has proven to be a field of research rich with possibilities for studying motional cooling, squeezing, quantum entanglement and metrology in solid state systems. While to date most studies have focused on the modulation of the cavity frequency by the moving element, the emergence of new materials will soon allow us to explore the influences of nonlinear optical effects. We therefore study in this work the effects due to a nonlinear position-modulated self-Kerr interaction and find that this leads to an effective coupling that scales with the square of the photon number, meaning that significant effects appear even for very small nonlinearities. This strong effective coupling can lead to lower powers required for motional cooling and the appearance of multistability in certain regimes.

I Introduction

Cavity optomechanics studies radiation-pressure-induced coherent photon-phonon interactions and has in recent years led to a rich trove of novel phenomena RevModPhys.86.1391 , including phonon cooling Teufel2011 ; Chan2011 , optomechanically induced transparency Weis1520 ; Safavi2011 , and mechanical squeezing Brooks2012 ; Purdy2013 ; Safavi2013 ; Wollman2015 ; Pirkkalainen2015 . It has also found use in other areas such as the generation of hybrid entanglement Wang2013 ; Palomaki2013 ; Vivoli2016 ; Riedinger2016 , quantum computation Schmidt2012 ; Rips2013 ; Houhou2015 , and precision sensing Forstner2012 ; Bagci2014 ; Wu2014 .

Nonlinear effects in such systems are currently a frontier research topic, and it is well understood that optomechanical systems with a linear optomechanical interaction, , can yield mechanical Kerr-type nonlinear optical responses Aldana2013 . Furthermore, optomechanical systems whose interactions are higher order in the position of the mechanical element, e.g. have been studied Vanner2011 ; Paraiso2015 ; Brawley2016 and shown to allow for new ways of coherent control of matter. Additionally a cross-Kerr interaction between the optical and mechanical modes, i.e. , was considered in Xiong2016 and was shown to stabilize the bistable solutions as well as leading to tristable solutions in certain parameter regimes. In this work we will extend the range of nonlinear phenomena in cavity optomechanics by considering a situation where a nonlinear medium is present in the cavity. This situation has recently attracted some attention where a material in the cavity was considered Kumar2010 ; Shahidani2013 , and mechanical resonators with large optical nonlinearities are currently under development Lu2014 ; Lu2015 . Another route to generate large optical nonlinearities is via coherent processes in atoms and the -system of Schmidt and Immamoglu Schmidt1996 is a well-known example. In our work, rather than considering a stationary optical nonlinearity, we will focus on the situation where the cavity’s optical nonlinearity is directly modulated by the mechanical position, e.g. . Such an interaction can be engineered in superconducting systems, cavity polaritonic systems and atom-optical systems. For example, a giant-self-Kerr microwave optical nonlinearity was recently shown to be possible in a superconducting coplanar resonator via a capacitive coupling between two Cooper-pair boxes Rebic2009 . By utilizing an electromechanical capacitor (such as in Ref. Teufel2011a ), a giant-Kerr mechanical modulation can then be straightforwardly engineered. Cavity polaritons, where light strongly couples to excitons in a quantum well or dot semiconductor hetrostructure, have also been studied for their use in optomechanics Kyriienko2014 , and ultrastrong optomechanical couplings have been described Jusserand2015 . The large interactions present in cavity polaritons are good candidates for optomechanical Kerr modulations to be expected Bobrovska2016 . Strong coupling between light and matter on the scale of individual atoms has recently been reported for atoms trapped near fiber tapers Kato2015 ; Polzik2016 , and the generation of giant-Kerr optical nonlinearities using electromagnetically induced transparency techniques of -systems (similar to Ref. Kumar2015 ), would also lead to a position dependent self-Kerr interaction.

In this paper we will describe the general situation of nonlinear optical cavity optomechanics and include both, the usual optomechanical coupling and the Kerr-type coupling. For this we will first derive the relevant Langevin equations and calculate the classical steady-state solutions. We will then study the quantum fluctuations about these and the spectrum of the fluctuations. Using a numerical analysis we will discuss how the inclusion of the Kerr nonlinear interaction alters the cooling rates and other key figures of merit and end by analyzing the appearance of optical multistability and the situation of position dependent absorption.

II Theoretical framework and analytic results

In the following we will first outline the model and the theoretical framework we use. From this we will derive the analytic equations that govern the physical properties of the system.

II.1 Basic model

The system we consider can be described by an extension of standard optomechanical setups, such as the membrane-in-the-middle model Bhattacharya2008 ; Thompson2008 ; Biancofiore2011 , where the membrane is modeled as a harmonic oscillator with a single mechanical frequency and nondimensional position and momentum operators . The cavity field is modeled as a harmonic oscillator and described by the bosonic creation and annihilation operators, and , which create photons with the resonant frequency . The membrane and the cavity interact via radiation pressure, which pushes the membrane and therefore changes the resonance frequency, making it position dependent . Since the harmonic oscillator is described by , this gives rise to a position-dependent interaction which is linear in the optical-field operators. While it is possible to perform the analytic treatment with no assumptions of the form of Biancofiore2011 , we will consider the case of

| (1) |

from the beginning as this clarifies the relation between the two types of interaction we will consider. Within the linearity assumption the optomechanical interaction is then described as .

The second type of interaction we consider is nonlinear in the optical field operators, which corresponds to a simultaneous two-photon process that can be facilitated by a material and is described by the term . In order to obtain a position-dependent interaction with a moving membrane the nonlinear coefficient has to become dependent on its position . If this can be engineered, then the nonlinear coefficient will be given similarly to the linear coefficient as

| (2) |

Throughout the paper we will generally use the dimensionless position-coordinate , but in order to derive the values of these coefficients for a specific physical system, it is easier to use the dimensional position coordinate , which is related to the nondimensional coordinate by some characteristic length scale as . Correspondingly, one can relate coupling strengths for the nondimensional coordinates to those of the dimensional coordinates by . The characteristic length scale in optomechanics is generally the zero-point motion of the mechanical element RevModPhys.86.1391 .

Physical implementation in an optical cavity

A model where the entire space between the two mirrors (where one of them can move) of a cavity is filled by a medium giving rise to a term was recently considered in Kumar2010 . We note that this model leads to a position dependence of as

| (3) |

and both, the resonant frequency and the cavity volume , depend on the position coordinate of the end mirror. Here is the vacuum permittivity, while is the length of the cavity and is the cavity volume, both in the absence of coupling. If we evaluate the first-order derivative at and use the form of the linear coupling in this setup , then we find that . This means that a relatively big nonlinear coupling can be achieved only when the cavity length is small. Since always holds, however, the interaction term will be small compared to . The photon blockade effects arising from the term which was the topic of the investigation in Ref. Kumar2010 would therefore obscure the physics of interest in this work.

Physical implementation in a microwave cavity

In order to overcome this issue and to obtain a variable strong nonlinear interaction we turn to a different setup in which is more tunable. It has been shown that a giant-self-Kerr microwave optical nonlinearity is possible in a superconducting coplanar resonator via a capacitive coupling between two Cooper-pair boxes Rebic2009 . While the details are too involved to present here (see Appendix), such a setup allows for a nonlinear coupling that depends on the mutual capacitance between the two Cooper-pair boxes. As the mutual capacitance depends on the distance between the plates, can be made dependent on by coupling the motion of one of the Cooper-pair boxes to the physical motion of a membrane. By manipulating the parameters within physically realistic constraints, nonlinear couplings of similar size to the typical linear couplings achievable in microwave cavities are obtainable (). The same caveat as in the optical case is still present, but due to the tunability of the artificial molecules it is possible to place a second molecule inside the cavity which does not couple to the position and has the same magnitude as but the opposite sign. See Appendix for more details and a discussion of the relevant physical parameters. As it is possible to engineer situations where , we will ignore the constant Kerr-term in our Hamiltonian, as it will generally lead to photon blockade which diminishes the effects of the nonlinear interaction that we want to investigate. Instead we consider just the position-modulated nonlinear term, described by the interaction Hamiltonian .

Finally the light field is produced by an input laser which has a frequency and an energy . The full Hamiltonian in the frame rotating at the driving laser frequency is then given by

| (4) |

Here the first term corresponds to the optical harmonic oscillator with detuning , while the second term corresponds to the single-frequency mechanical oscillator and the third term corresponds to the the input laser field of strength . The last two terms account for the linear and nonlinear interactions as described above.

II.2 Quantum Langevin formalism

The optomechanical setup we are considering is an open system and interactions with the environment in the form of photon losses, mechanical dissipation, and noise have to be taken into account. We do this by utilizing the quantum Langevin formalism and consider photon loss associated with the end mirrors of the cavity and photon loss associated with a moving element, such as a membrane . While experimental evidence suggest that the dependence of on the position is usually small Karuza2012 , we take it into account to get the most general picture. The losses have associated noise operators and , which have the correlation relation Biancofiore2011

| (5) |

In addition to the losses associated with the optical field, mechanical dissipation of the membrane must be considered. For this the associated noise operator has the correlation relation

| (6) |

where is the Fourier space frequency and

| (7) |

is the mean phonon number at temperature and is the derivative of the Dirac-delta function. Adding these to the Heisenberg equations for the Hamiltonian (4) we arrive at the quantum Langevin equations (QLE)

| (8) | |||

| (9) | |||

| (10) |

The term is an effective noise term arising from the absorption in the membrane, as long as it is not assumed constant Biancofiore2011 . Solving this full set of quantum-mechanical equations is not a trivial task and we therefore employ a semiclassical approximation where we assume the physical operators can be expressed as a classical average plus some small quantum fluctuation

| (11) |

This assumption only holds when the classical part is large, which is the situations experiments are commonly in. In the next section we will look at various aspects of the solutions for the system.

II.3 Classical steady-state solutions

To determine the classical steady-state solutions we consider the quantum fluctuations to be small compared to the classical c-numbers, so that any terms containing them can be neglected. Setting all derivatives in the QLE to zero then leads to

| (12) | ||||

| (13) |

where . Assuming that these two coupled equations can be expressed as a single seventh-order polynomial for the mean photon number of the form

| (14) |

Even though this seventh-order polynomial equation has in principle seven roots, all complex solutions can be discarded as the mean photon number has to be real. The steady-state position of the membrane can then be found by inserting the resulting solution for into expression (12). We note that doing a similar analysis for the linear system leads to a third-order polynomial only.

II.4 Linearised quantum Langevin equations: Effect of quantum fluctuations

To determine the stability of the steady-state solutions and to calculate physical values that depend solely on the quantum fluctuations, such as the temperature of the membrane, we will in this section look at the effects of the fluctuation terms. For this we use the quadratures of the electric field , , and and insert the steady-state solution plus the quantum-fluctuations into the QLEs. We are still considering the quantum fluctuations and the noise operators to be small and therefore only keep terms up to first order in these operators. This leads to the linearized quantum Langevin equations (LQLE) of the form

| (15) | |||

| (16) | |||

| (17) | |||

| (18) |

where we have defined the effective loss rate due to the position-dependent as and the overall effective coupling in the system as . Additionally we have defined the effective detuning . It is worth noting that the nonlinear coupling enters the effective coupling scaled with the mean photon number in the cavity and it can therefore be expected to have a much stronger effect than the linear coupling.

The LQLE can be rewritten as the matrix equation of the form

| (19) |

where

| (20) |

and

| (21) |

The drift matrix is given by

| (22) |

and can be seen to reduce to the linear drift matrix for Biancofiore2011 . The four eigenvalues appear as complex conjugate pairs and give information about the quantum fluctuations in the system. Their real parts corresponds to the cooling (or heating rate) of the membrane and the cavity, which means that the system is only stable if both of these are negative and the system relaxes towards a steady state. The imaginary parts describe the dressed eigenfrequencies of the membrane and the optical field. The stationary state is characterized by the covariance matrix V, which is determined by the Lyapunov equation

| (23) |

and where D, known as the diffusion matrix, is related to the noise vector by Biancofiore2011

| (24) |

It is explicitly given by Biancofiore2011

| (25) |

The mean occupation number for the phonons can be obtained from the mean energy of the mechanical resonator which is given by

| (26) |

where and are matrix elements from the covariance matrix.

The spectral function for the system is defined as Kumar2010

| (27) |

where is the Fourier space frequency. Taking the Fourier transformation of the LQLE one finds

| (28) |

where and with and . Using the correlation relations for the noise operators in Fourier space then gives the spectrum

| (29) |

where the thermal and radiation pressure spectra are given by

| (30) | ||||

| (31) |

and we have an extra noise spectrum associated with membrane absorption

| (32) |

Here us the effective susceptibility and is given by

| (33) | |||

| (34) | |||

| (35) |

Again we note that the spectrum reduces to the linear one discussed in Ref. Biancofiore2011 if we assume that .

III Numerical results

To stress the effects stemming from the nonlinear nature of the coupling, we focus in the following on results that show significant differences to the linear situation. Furthermore, for the clearest comparison we initially make the approximation that , which reduces the problem to the standard optomechanical setup. This approximation is also consistent with existing experimental data for a linear membrane Karuza2012 . In general the behavior of our system can be distinguished into two categories. In the first one, and have the same sign and thus enhance each other. In this regime the nonlinear coupling leads to a very strong effective coupling but no qualitative differences from the system where only a linear coupling is present. In the second category and have opposite signs, i.e., one of them is attractive and the other is repulsive. Here a parameter regime exists for which additional steady-state solutions, that are not present for the linear system, can be found. These arise from the seventh-order polynomial describing the steady state of the nonlinear system. In our calculations we use a mechanical frequency of and a loss rate of corresponding to the experimental values in Ref. Karuza2012 . We generally employ a mechanical dissipation given by and choose a temperature which gives an initial phonon number of .

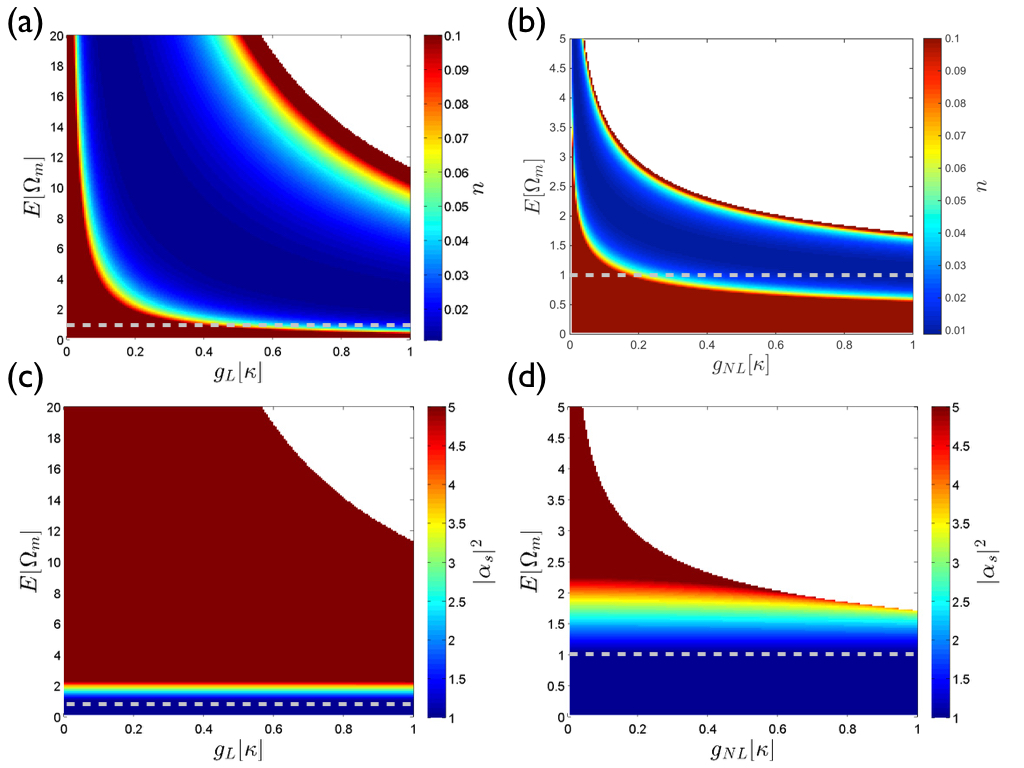

III.1 Nonlinear enhancement

The phonon number as a function of the input energy of the laser and the linear and nonlinear couplings, respectively, for is shown in Figs. 1(a) 1(b). This corresponds to the resolved sideband regime where optimal cooling can be expected. One can see that for any value of or there is a value of for which the same maximal cooling () is obtained and this value reduces as the coupling strength is increased. In fact, the nonlinear coupling simply enhances this behavior that is already present in the linear case, reducing the value of required to achieve the same amount of cooling as in the linear case. Additionally one can see a rise in temperature as increases beyond the value for maximal cooling, until the solutions become unstable (white areas in the figures). The photon numbers for the same parameter ranges are plotted in Figs. 1(c) and 1(d). One can see that they generally increase with energy as one would expect; however, it is more relevant to confirm whether the photon number stays above 1 in the regime of relevance, i.e., the regime of maximal cooling, since our model is otherwise inapplicable. In fact, for very small values of it drops below 1 and to get maximal cooling for large values of , values of approaching this inapplicable regime must be chosen. For the most part, however, this limitation does not pose a problem. Situations where both and are finite behave similarly to the two limiting cases discussed here.

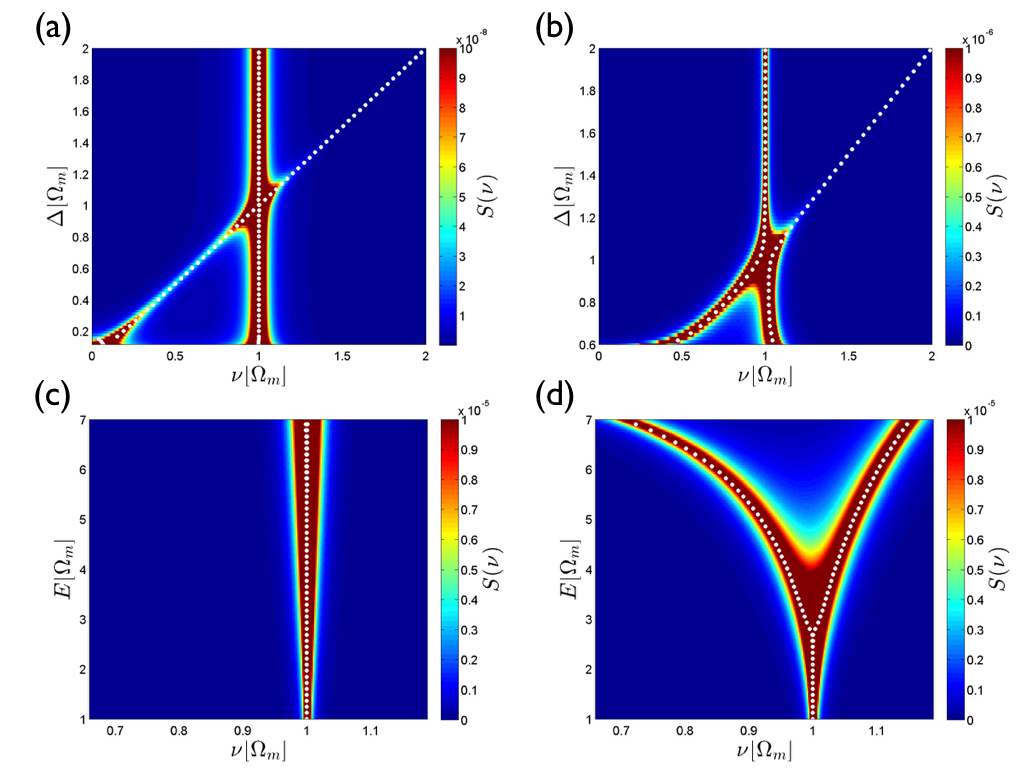

To investigate the existence of a strong-coupling regime at small laser intensities, we will look next at the spectrum for and . In both cases we have a fairly weak linear coupling and therefore do not expect the first case to be in the strong-coupling regime. The spectrum as a function of the detuning at is plotted in Figs. 2(a) and 2(b), and one can see that without the nonlinear coupling the system is indeed in the weak-coupling regime (no splitting is visible). However, adding a comparatively small amount of nonlinear coupling, , brings the system into the strong-coupling regime, signified by the avoided crossing of the dressed eigenfrequencies. This is quite remarkable as it allows for strong coupling at much smaller laser energies by adding just a small nonlinearity to the system. The spectrum as a function of the energy at , is plotted in Figs. 2(c) and 2(d), where the normal-mode splitting for the nonlinear coupling is distinctly visible and clearly absent for the linear case at these energies. The figures also shows that our results are self-consistent as the imaginary part of the eigenvalues of the drift matrix (dotted white lines) correspond to the two peak positions in frequency space.

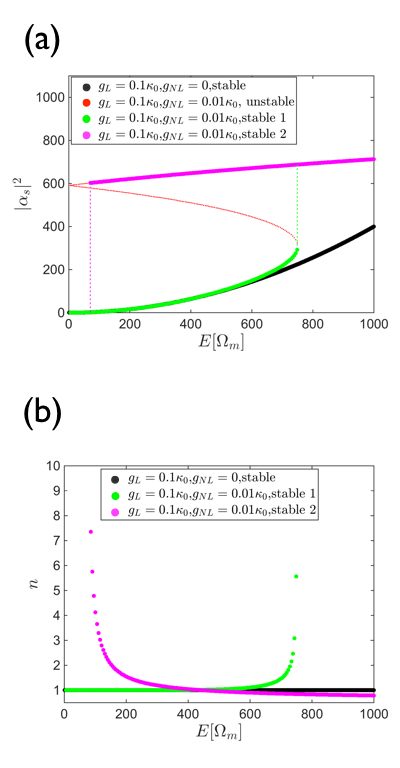

Another situation where the dramatic effect of a small nonlinearity becomes visible is shown in Fig. 3(a). Here the photon number is given as a function of for and at . The linear system can be seen to have only one solution in the displayed energy range, but adding the small nonlinearity leads to optical bistability as evidenced by the characteristic S-shaped curve. Starting at and slowly increasing the energy the system moves along the first stable solution with the smallest number of photons. When this solution becomes unstable there is a first order transition to the second stable solution which has the largest number of photons. If the energy is then decreased the system stays in this second steady state until it becomes unstable at which point a first-order transition to the first steady state takes place. This is the characteristic signature of optical hysteresis. In Fig. 3(b) the corresponding phonon numbers are plotted. The temperature (phonon number) of the solutions are fairly constant in the stable regimes but rise rapidly as a solution becomes unstable.

It is worth stressing again that this optical bistability appears at quite low energies, because the nonlinearity leads to strong effective coupling. To see bistability with linear coupling only, much larger energies would be needed.

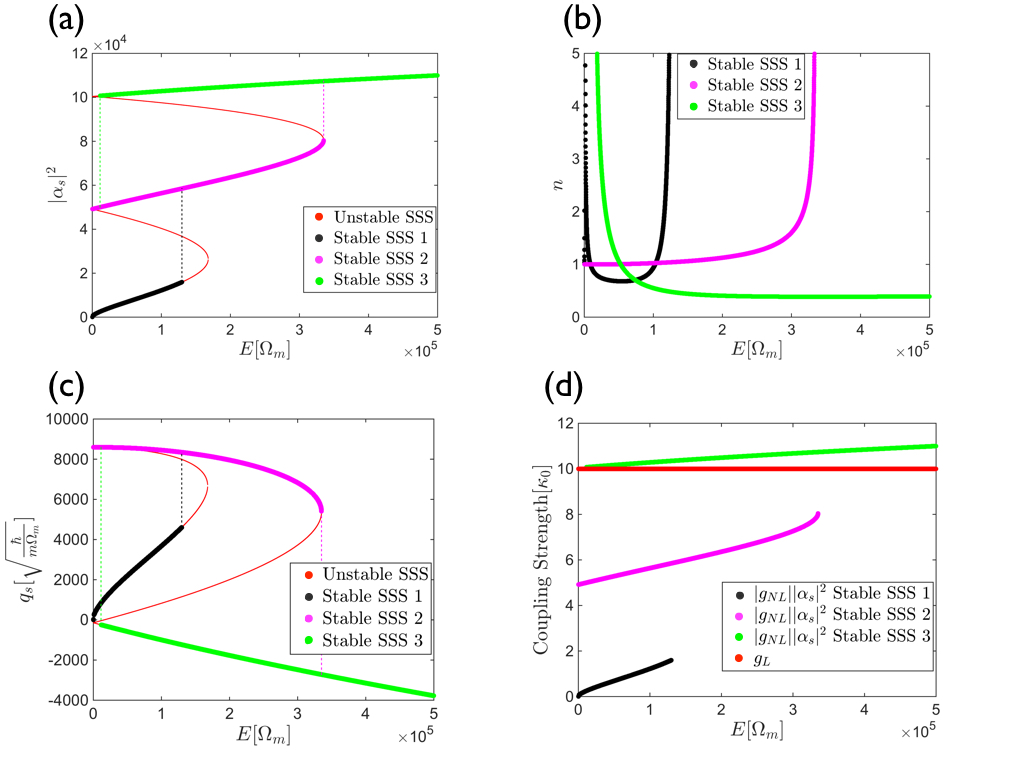

III.2 Optical multistability

While we have shown above that choosing the linear and the nonlinear coupling strength to have the same sign leads to mostly an enhancement of the effects already present in the linear case, qualitatively new effects can appear when they have opposite signs. For this we consider in the following and . The reason for the large difference between the linear and the nonlinear coupling strength is that if the couplings were chosen to be of comparable size, the nonlinear coupling will dominate the system as it enters the effective coupling scaled with the photon number, i.e., . Therefore, in order to engineer competition between the two forces, values for which the contribution of the nonlinear coupling and the linear coupling are comparable must be chosen. In Fig. 4 we show the behavior of and . Five steady-state solutions can be found, but only three of them are stable. To ease the discussion we will denote the three stable branches as 1, 2, and 3, where 1 corresponds to the stable solution with the smallest number of photons, 2 corresponds to the middle solution, while 3 corresponds to the solution with largest photon number [see Fig. 4(a)]. For increasing , starting from the system will be in a state on the first branch, jump to the second branch at energies where the first branch is no longer stable, before finally moving to the third branch. Looking at the position of the membrane for these states, one can see from Fig. 4(c) that it moves in the positive direction along the first branch, then changes direction and moves in the negative direction along the second branch, and, finally, jumps to a negative value moving in the negative direction when the system enters the third branch. This means that as the system jumps from the second to the third branch, the position of the membrane should jump from being displaced in the positive direction to being displaced in the negative one. Since one can understand this behavior by looking at the size of and , which is plotted in Fig. 4(d). Along the first branch , which is positive, is dominant and so the membrane is pushed in the positive direction. Along the second branch , which depends on the photon number, becomes comparable with and though stays positive the effective coupling becomes negative. Increasing values of mean an effective decrease in the (positive) position . On the third branch is always much larger than and therefore the membrane has a negative effective coupling, while also being at a negative value in position space. This means that the system moves between attractive and repulsive regimes for the interaction between the membrane and the cavity field as it jumps between stable solutions. Finally, looking at the phonon number in Fig. 4(b), one can see that the temperature (phonon number) of the second branch is considerably higher than that of the other two, with the third branch having the lowest temperature.

III.3 Effect of position-dependent absorption

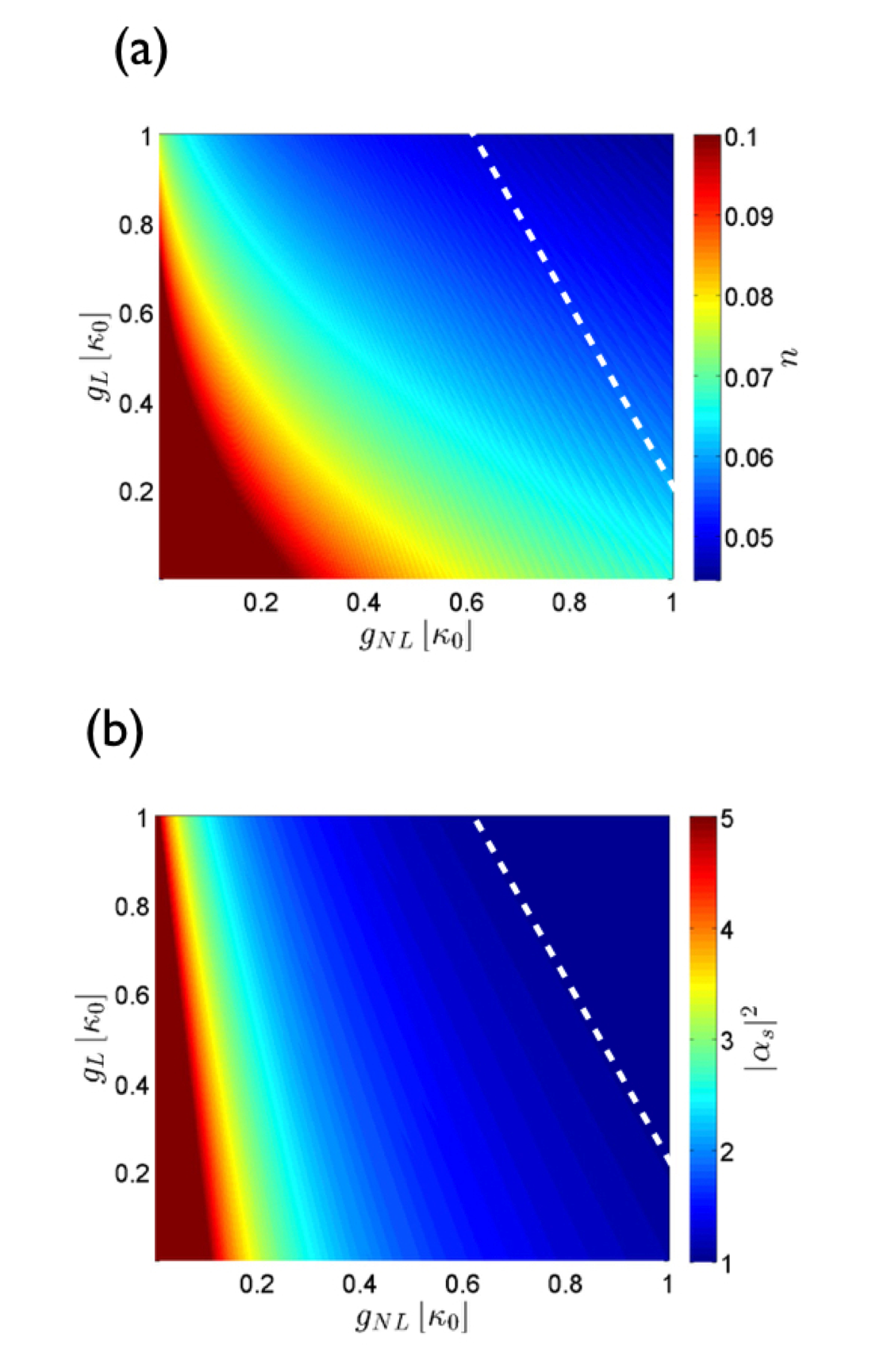

Finally we consider the case of letting the membrane absorption depend on the position, i.e., with and , and study how this affects the cooling in the resolved sideband regime, where . For this, the phonon number and the photon number as a function of and are shown in Fig. 5, where the energy at each point has been chosen so as to minimize . One can see that the position dependent absorption coefficient leads to overall worse cooling [compare with from Figs. 1 (a) and 1 (b)], which is to be expected. However, by increasing the coupling this trend can be counteracted, leading to more efficient cooling for a more strongly coupled system. As can be seen from Fig. 5 this favors the nonlinear coupling, which is always stronger than the linear coupling. Therefore in this case the nonlinear coupling can lead to more efficient cooling. Looking at the photon number however, one must be wary as the energy for which optimal cooling is obtained corresponds to photon numbers on the order of one for very strongly coupled systems. While this means that the basic assumption for our model breaks down, we find enhanced cooling for the majority of the investigated ranges without encountering this problem.

IV Conclusion

Applying the Langevin formalism we have derived the classical steady-state solutions and the spectrum of quantum fluctuations for a generic optomechanical system including a nonlinear position-modulated self-Kerr optomechanical interaction. We find that the the effective nonlinear coupling scales with the square of the photon number, which implies that even for a small nonlinear coupling the system enters the strong-coupling regime. By analyzing the obtained solutions numerically this is confirmed as a small nonlinear coupling leads to normal-mode splitting and an avoided crossing in the spectrum, which is associated with the strong-coupling regime. This also leads to lower powers being required for motional cooling and bistability compared to systems where only a linear coupling is present. Furthermore, we find that the addition of a weak nonlinear coupling with the opposite sign of the linear coupling leads to three stable solutions, who can all be occupied as a function of the energy. Finally, we find that in the case of position-dependent absorption the nonlinear coupling can help counteract the degradation of cooling previously predicted in this regime. All these effects are consistent with a strong effective nonlinear coupling, even at small coupling strengths . This means that engineering an effective nonlinear system experimentally is easier than what would initially be assumed, as only a small nonlinearity is required to observe dramatic effects.

Since it is known that nonlinear systems can support self-sustained oscillations and researchers have investigated these in the case of optomechanical systems possessing motional Kerr optical nonlinearities Mar2006 ; Lud2008 , we expect that with nonlinear optical coupling the behavior of such self-sustained oscillations may be even richer and an interesting topic for future investigations. Some possible avenues of experimental realization for such systems are cavity polaritons Bobrovska2016 and atoms trapped near fibre tapers Kato2015 ; Polzik2016 , but the most promising one is utilizing artificial multilevel cooper pair box molecules in a microwave cavity Rebic2009 , which we discuss in the appendix of this paper.

Acknowledgment

This project was supported by the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University and the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Engineered Quantum Systems.

Appendix: Obtaining the nonlinear coupling constant from an electromechanical microwave setup

We consider the artificial multilevel cooper pair box molecule interacting with a microwave coplanar resonator, as described in Ref. Rebic2009 . The general idea is to engineer an artificial atom as a four-level N-system, and to create a Kerr nonlinearity using a scheme similar to the EIT scheme for atoms introduced by Schmidt and Immamoglu Schmidt1996 . For this the four-level effective Hamiltonian in terms of the electric properties of the superconducting circuit is derived, which gives explicit descriptions of the nonlinear coupling coefficients. Since the mutual capacitance between the cooper pair boxes depends on the distance between them, the capacitance becomes position-dependent if one of the boxes is coupled to a moving membrane. This leads to a parametric dependence on the position of the form

| (36) |

where is the vacuum permittivity, is the permittivity of the material between the plates, is the area of both plates ,and is the initial distance between the plates. This means that any quantity, including which depends on the capacitance , becomes position-dependent as well. In Ref. Rebic2009 it is shown that the nonlinear coefficient in the regime where is given by

| (37) |

where and are the detunings between the cavity frequency and the fourth and second energy states and , respectively. The are the spontaneous decay rates from to , and are the coupling strengths between and , respectively, and, finally, is the coupling between and (see Fig. 1 in Ref. Rebic2009 ). The position-dependence is contained in the two detunings and as these depend on . Analytic expressions for the these detunings can be found at the coresonance point where they become equal, , and are given by Rebic2009

| (38) |

where

| (39) |

with and . Here is the elementary charge, while are capacitances coming from different parts of the circuit (see. Fig. 2 in Ref. Rebic2009 for a diagram of the circuit). Depending on the setup, the resonant frequency can also be dependent on the the position coordinate (and in fact has to be if we wish to engineer a linear coupling). In order to simplify our estimate of the nonlinear coefficient, we will also assume that and (similarly to Ref. Rebic2009 ), which leads to

| (40) |

To find the nonlinear coefficient we then need to evaluate the derivative of at (see Sec. II.A), which we can obtain analytically by simply taking the derivative of Eq. (40). In order to evaluate at we require

| (41) |

and

| (42) |

To estimate the obtainable sizes of and we need to input physically realistic values for the different parameters. We use estimates similar to those in Ref. Rebic2009 , . Additionally, we model the mutual capacitance, using values corresponding to those in the experimental setup from Ref. Teufel2011 with and use a similar cavity frequency as well as assuming a linear coupling equivalent to what they obtain, . Finally, we use the values Gywat2006 . It turns out that is a useful knob for changing , while keeping the other values constant, and one can get a large range of values for the nonlinear coefficients: For example, for we get , while gives . The nonlinear coupling can be tuned over several orders of magnitude and while much smaller values than the ones depicted above are easily obtainable, the main takeaway is that the nonlinear coupling can be made comparable in size to the linear coupling. To get the nondimensional coupling coefficients we multiply by the zero-point position from the experimental setup in Ref. Teufel2011 which for the first case above corresponds to . Finally, we note that it is possible to place a second artificial molecule within the cavity, which does not couple to the position element, in such a way that the term is canceled out. This is important, as it allows the nonlinear interaction term to be engineered without the photon blockade effect associated with the term. In order to engineer a value of the same size with the opposite sign, the easiest way is to simply engineer a detuning with the opposite sign, i.e., , keeping the other parameters constant. By allowing the parameters to vary as well there are, however, many more ways to engineer an artificial molecule which cancels .

References

- (1) M. Aspelmeyer, T.J. Kippenberg and F. Marquardt, Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 1391 (2008)

- (2) J.D. Teufel, T. Donner, D. Li, J.W. Harlow, M.S. Allman, K. Cicak, A.J. Sirois, J.D. Whittaker, K.W. Lehnert and R.W. Simmonds, Nature 475, 359 (2011)

- (3) J. Chan, T.P. Mayer Alegre, A.H. Safavi-Naeini, J.T. Hill, A. Krause, S. Groeblacher, M. Aspelmeyer and O. Painter, Nature 478, 89 (2011)

- (4) S. Weis, R. Rivi’ere, S. Del’eglise, E. Gavartin, O. Arcizet, A. Schliesser and T.J. Kippenberg, Science 330, 1520 (2010)

- (5) A.H. Safavi-Naeini, T.P.M. Alegre, J. Chan, M. Eichenfield, M. Winger, Q. Lin, J.T. Hill, D.E. Chang and O. Painter, Nature 472, 69 (2011)

- (6) D.W.C. Brooks, T. Botter, S. Schreppler, T.P. Purdy, N. Brahms and D.M. Stamper-Kurn, Nature 488, 476 (2012)

- (7) T.P. Purdy, P.L. Yu, R.W. Peterson, N.S. Kampel and C.A. Regal, Phys. Rev. X 3, 031012 (2013)

- (8) A.H. Safavi-Naeini, S. Groeblacher, J.T. Hill, J. Chan, M. Aspelmeyer and O. Painter, Nature 500, 185 (2013)

- (9) E.E. Wollman, C.U. Lei, A.J. Weinstein, J. Suh, A. Kronwald, F. Marquardt, A.A. Clerk and K.C. Schwab, Science 349, 952 (2015)

- (10) J.M. Pirkkalainen, E. Damskagg, M. Brandt, F. Massel and M.A. Sillanpaa, Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 243601 (2015)

- (11) Y.D. Wang, and A.A. Clerk, Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 253601 (2013)

- (12) T.A. Palomaki, J.D. Teufel, R.W. Simmondsand K.W. Lehnert, Science 342, 710 (2013)

- (13) V.C. Vivoli, T. Barnea, C. Galland and N. Sangouard, Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 070405 (2016)

- (14) R. Riedinger, S. Hong, R.A. Norte, J.A. Slater, J. Shang, A.G. Krause, V. Anant, M. Aspelmeyer and S. Groblacher, Nature 530, 313 (2016)

- (15) M. Schmidt, M. Ludwig and F. Marquardt, New J. Phys. 14, 125005 (2012)

- (16) S. Rips and M.J. Hartmann, Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 120503 (2013)

- (17) O. Houhou, H. Aissaoui and A. Ferraro, Phys. Rev. A 92, 063843 (2015)

- (18) S. Forstner, S. Prams, J. Knittel, E.D. van Ooijen, J.D. Swaim, G.I. Harris, A. Szorkovszky, W.P.Bowen and H. Rubinsztein-Dunlop, Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 120801 (2012)

- (19) T. Bagci, A. Simonsen, S. Schmid, L.G. Villanueva, E. Zeuthen, J. Appel, J.M. Taylor, A. Sorensen, K. Usami, A. Schliesser and E.S. Polzik, Nature 507, 81 (2014)

- (20) M. Wu, A.C. Hryciw, C. Healey, D.P. Lake, H. Jayakumar, M.R. Freeman, J.P. Davis and P.E. Barclay, Phys. Rev. X 4, 021052 (2014)

- (21) S. Aldana, C. Bruder and A. Nunnenkamp, Phys. Rev. A 88, 043826 (2013)

- (22) M.R. Vanner, Phys. Rev. X 1, 021011 (2011)

- (23) T.K. Paraiso, M. Kalaee, L. Zang, H. Pfeifer, F. Marquardt and O. Painter, Phys. Rev. X 5, 041024 (2015)

- (24) G.A. Brawley, M.R. Vanner, P.E. Larsen, S. Schmid, A. Boisen and W.P. Bowen, Nature Comms. 7, 10988 (2016)

- (25) W. Xiong, D.-Y. Jin, Y. Qiu, C.-H. Lam and J. Q. You, Phys.Rev. A 93, 023844 (2016)

- (26) T. Kumar, A.B. Bhattacherjee and ManMohan Phys.Rev.A 81, 013835 (2010)

- (27) S. Shahidani, M.H. Naderi and M. Soltanolkotabi, Phys. Rev. A 88, 053813 (2013)

- (28) X. Lu, J.Y. Lee, S. Rogers and Q. Lin, Opt. Express 22, 30826 (2014)

- (29) X. Lu, J.Y. Lee and Q. Lin, Sci. Rep. 5, 17005 (2015)

- (30) H. Schmidt and A. Imamoglu, Opt. Lett. 21, 1936 (1996)

- (31) S. Rebic, J. Twamley and G.J. Milburn, Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 150503 (2009)

- (32) J.D. Teufel, D. Li, M.S. Allman, K. Cicak, A.J. Sirois, J.D. Whittaker and R.W. Simmonds, Nature 471, 204 (2011)

- (33) O. Kyriienko, T.C.H. Liew and I.A. Shelykh, Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 076402 (2014)

- (34) B. Jusserand, A.N. Poddubny, A.V. Poshakinskiy, A. Fainstein and A. Lemaitre, Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 267402 (2015)

- (35) N. Bobrovska, M. Matuszewski, T.C.H. Liew and O. Kyriienko, Phys. Rev. B 95, 085309 (2017)

- (36) S. Kato and T. Aoki, Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 093603 (2015)

- (37) H.L. Sørensen, J.B. B’eguin, K.W. Kluge, I. Iakoupov, A.S. Sørensen, J.H. Müller, E.S. Polzik and J. Appel, Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 133604 (2016)

- (38) R. Kumar, V. Gokhroo and S. Nic Chormaic New J. Phys. 17, 123012 (2015)

- (39) M. Bhattacharya, H. Uys and P. Meystre, Phys. Rev. A 77, 033819 (2008)

- (40) J.D. Thompson, B.M. Zwickl, A.M. Jayich, F. Marquardt, S.M. Girvin and J.G.E. Harris, Nature 452, 72 (2008)

- (41) C. Biancofiore, M. Karuza, M. Galassi, R. Natali, P. Tombesi, G. Di Giuseppe and D. Vitali, Phys. Rev. A 84, 033814 (2011)

- (42) M. Karuza, C. Molinelli, M. Galassi, C. Biancofiore, R. Natali, P. Tombesi, G. Di Giuseppe and D. Vitali, New J. Phys. 14, 095015 (2012)

- (43) F. Marquardt, J.G.E. Harris and S.M. Girvin, Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 103901 (2006)

- (44) M. Ludwig, B. Kubala, and M. Marquardt, New J. Phys. 10, 095013 (2008)

- (45) O. Gywat, F. Meier, D. Loss and D. Awschalom, Phys.Rev. B 73, 125336 (2006)