Power of Knockoff: The Impact of Ranking Algorithm, Augmented Design, and Symmetric Statistic

Abstract

The knockoff filter is a recent false discovery rate (FDR) control method for high-dimensional linear models. We point out that knockoff has three key components: ranking algorithm, augmented design, and symmetric statistic, and each component admits multiple choices. By considering various combinations of the three components, we obtain a collection of variants of knockoff. All these variants guarantee finite-sample FDR control, and our goal is to compare their power. We assume a Rare and Weak signal model on regression coefficients and compare the power of different variants of knockoff by deriving explicit formulas of false positive rate and false negative rate. Our results provide new insights on how to improve power when controlling FDR at a targeted level. We also compare the power of knockoff with its propotype - a method that uses the same ranking algorithm but has access to an ideal threshold. The comparison reveals the additional price one pays by finding a data-driven threshold to control FDR.

Keywords: CI-knockoff, Hamming error, phase diagram, Rare/Weak signal model, SDP-knockoff, variable ranking, variable selection

1 Introduction

We consider a linear regression model, where is the vector of responses and is the design matrix. We assume

| (1.1) |

Driven by the interests of high-dimensional data analysis, we assume is large and is a sparse vector (i.e., many coordinates of are zero). Variable selection is the problem of estimating the true support of . Let denote the set of selected variables. The false discovery rate (FDR) is defined to be

Controlling FDR is a problem of great interest. When the design is orthogonal (i.e., is a diagonal matrix), the BH-procedure (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) can be employed to control FDR at a targeted level. When the design is non-orthogonal, the BH-procedure faces challenges, and several recent FDR control methods were proposed, such as the knockoff filter (Barber and Candès, 2015), model-X knockoff (Candes et al., 2018), Gaussian mirror (Xing et al., 2023), and multiple data splits (Dai et al., 2022). All these methods are shown to control FDR at a targeted level, but their power is less studied. This paper aims to provide a theoretical understanding to the power of FDR control methods.

We introduce a unified framework that captures the key ideas behind recent FDR control methods. Starting from the seminal work of Barber and Candès (2015), this framework has been implicitly used in the literature, but it is the first time that we abstract it out:

-

(a)

There is a ranking algorithm, which assigns an importance metric to each variable.

-

(b)

An FDR control method creates an augmented design matrix by adding fake variables.

-

(c)

The augmented design and the response vector are supplied to the ranking algorithm as input, and the output is converted to a (signed) importance metric for each original variable through a symmetric statistic.

The three components, ranking algorithm, augmented design, and symmetric statistic, should coordinate so that the resulting importance metrics for null variables () have symmetric distributions and that the importance metrics for non-null variables () are positive with high probability. When these requirements are satisfied, one can mimic the BH procedure (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) to control FDR at a targeted level.

The choices of the three components are not unique. For example, we may use any linear regression method as the ranking algorithm, where we assign as the importance metric for variable . Similarly, the other two components also admit multiple choices. This leads to many different combinations of the three components. The literature has revealed insights on how to choose these components to get a valid FDR control, but there is little understanding on how to design them to boost power. The main contribution of this paper is dissecting and detailing the impact of each component on the power.

1.1 Main results and discoveries

We start from the orthodox knockoff in Barber and Candès (2015), which uses Lasso as the ranking algorithm, a semi-definite programming (SDP) procedure to construct the augmented design, and the signed maximum function as the symmetric statistic. We then replace each component of the orthodox knockoff by a popular alternative choice in the literature. We compare the power of the resulting variant of knockoff with the power of the orthodox one. This serves to reveal the impact of each component on power.

Our results lead to some noteworthy discoveries: (i) For the choice of symmetric statistic, the signed maximum is better than a popular alternative - the difference statistic; (ii) For the choice of the augmented design, the SDP approach in orthodox knockoff is less favored than a recent alternative - the conditional independence approach (Liu and Rigollet, 2019); (iii) For the choice of ranking algorithm, we compare Lasso and least-squares and find that Lasso has an advantage when the signals are extremely sparse and least-squares has an advantage when the signals are moderately sparse.

For each variant of knockoff, we also consider its prototype, which applies the ranking algorithm to the original design and selects variables by applying an ideal threshold on the importance metrics output by the ranking algorithm. We note that the core idea of knockoff is hinged on the other two components - augmented design and symmetric statistic, as these two components serve to find a data-driven threshold on importance metrics. Therefore, the comparison of knockoff and its prototype reveals the key difference between FDR control and variable selection - we need to pay an extra price to find a data-driven threshold. If an FDR control method is designed effectively, it should have a negligible power loss compared with its prototype. In the knockoff framework, when the design is orthogonal or blockwise diagonal and when the ranking algorithm is Lasso, we can show that knockoff (with proper choices of augmented design and symmetric statistic) indeed yields a negligible power loss compared with its own prototype. On the other hand, this is not true for a general design or when the ranking algorithm is not Lasso.

1.2 The theoretical framework and criteria of power comparison

Let be the Gram matrix. Without loss of generality, we assume that each column of has been normalized so that the diagonal entries of are all equal to .111We use a conventional normalization of in the study of Rare/Weak signal models. It is different from the standard normalization where the diagonal entries of are assumed to be . We note that our is actually in the standard normalization. This is why disappears in the order of nonzero . We study a challenging regime of “Rare and Weak signals” (Donoho and Jin, 2015; Jin and Ke, 2016), where for some constants and , we consider settings where

The two parameters, and , characterize the signal rarity and signal weakness, respectively. Here, is the minimax order for a successful inference of the support of (Genovese et al., 2012), and the constant factor drives subtle phase transitions. This model is widely used in multiple testing (Donoho and Jin, 2004; Arias-Castro et al., 2011; Barnett et al., 2017) and variable selection (Ji and Jin, 2012; Jin et al., 2014; Ke et al., 2014).

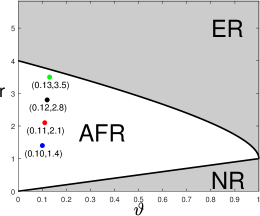

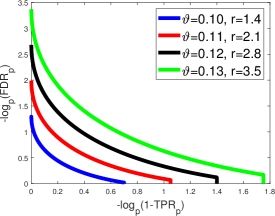

The power of an FDR control method depends on the target FDR level . Instead of fixing , we derive a trade-off diagram between FDR and the true positive rate (TPR) as varies. This trade-off diagram provides a full characterization of power, for any given model parameters . We also derive a phase diagram (Jin and Ke, 2016) for each FDR control method. The phase diagram is a partition of the two-dimensional space into different regions, according to the asymptotic behavior of the Hamming error (i.e., the expected sum of false positives and false negatives). The phase diagram provides a visualization of power for all together. Both the FDR-TPR trade-off diagram and phase diagram can be used as criteria of power comparison. We prefer the phase diagram, because a single phase diagram covers the whole parameter range (in contrast, the FDR-TPR trade-off diagram is tied to a specified ). Throughout the paper, we use phase diagram to compare different variants of knockoff. At the same time, we also give explicit forms of false positive rate and false negative rate, from which the FDR-TPR trade-off diagram can be deduced easily.

1.3 Related literature

Power analysis of FDR control methods is a small body of literature. Su et al. (2017) set up a framework for studying the trade-off between false positive rate and true positive rate across the lasso solution path. Weinstein et al. (2017) and Weinstein et al. (2021) extended this framework to find a trade-off for the knockoff filter, when the ranking algorithm is the Lasso and thresholded Lasso, respectively. These trade-off diagrams are for linear sparsity (number of nonzero coefficients of is a constant fraction of ) and independent Gaussian designs ( are iid variables). However, their analysis and results do not apply to our setting: In our setting, is much sparser, and the overall signal strength as characterized by is much smaller. Furthermore, we are primarily interested in correlated designs, but their study is mostly focused on iid Gaussian designs.

For correlated designs, Liu and Rigollet (2019) gave sufficient and necessary conditions on such that knockoff has a full power, but they did not provide an explicit trade-off diagram. Moreover, their analysis does not apply to the orthodox knockoff but only to a variant of knockoff that uses de-biased Lasso as the ranking algorithm. Beyond linear sparsity, Fan et al. (2019) studied the power of model-X knockoff for arbitrary sparsity, under a stronger signal strength: we assume , while they assumed . In a similar setting, Javanmard and Javadi (2019) studied the power of using de-biased Lasso for FDR control. Our paper differs from these works because we study the regime of weaker signals and also derive the explicit FDR-TPR trade-off diagrams and phase diagrams.

Wang and Janson (2022) and Spector and Janson (2022) studied the power of model-X knockoff and conditional randomization tests. They considered linear sparsity and iid Gaussian designs, and found a disadvantage of power by constructing augmented design as in the orthodox knockoff (with least-squares as the ranking algorithm). This qualitatively agrees with some of our conclusions in Section 5, but it is for a different setting with uncorrelated variables and linear sparsity. We also study more variants of knockoff than those considered in aforementioned works. Recently, Li and Fithian (2021) recast the fix-X knockoff as a conditional post-selection inference method and studied its power.

In a sequel of papers (Ji and Jin, 2012; Jin et al., 2014; Ke et al., 2014), the Rare/Weak signal model was used to study variable selection. They focused on the class of Screen-and-Clean methods for variable selection and proved its optimality under various design classes. We borrowed the notion of phase diagram from these works. However, they did not consider any FDR control method and their methods do not apply to knockoff. Different from the proof techniques employed by the aforementioned work, our proof is based on a geometric approach, where the key is studying the geometric properties of the “rejection region” induced by knockoff (see Section 7 for details).

1.4 Organization

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the idea of knockoff. Section 3 introduces the Rare/Weak signal model and explains how to use it as a theoretical platform to study and compare the power of FDR control methods. Sections 4-6 contain the main results, where we study the impact of symmetric statistic, augmented design, and ranking algorithm, respectively. Section 7 sketches the proof and explains the geometrical insight behind the proof. Section 8 contains simulation results. Section 9 concludes with a short discussion. Detailed proofs are relegated to the Appendix.

2 The knockoff filter, its variants and prototypes

Let us first review the orthodox knockoff filter (Barber and Candès, 2015). Write and let , with , be a nonnegative diagonal matrix (to be chosen by the user) such that . The knockoff first creates a design matrix such that

| (2.1) |

Let and be the th column of and , respectively, . Here, is called a knockoff of variable . For any , let be the solution of Lasso (Tibshirani, 1996) on the expanded design matrix with a tuning parameter :

| (2.2) |

For each , let and . The importance of variable is measured by a symmetric statistic

| (2.3) |

where is a bivariate function satisfying . Here are (signed) importance metrics for variables. Under some regularity conditions, it can be shown that has a symmetric distribution when and that is positive with high probability when . Given a threshold , the number of false discoveries is equal to

where the first approximation is based on the symmetry of the distribution of for null variables and the second approximation comes from the sparsity of . The right hand side gives an estimate of the number of false discoveries. Hence, a data-driven threshold to control FDR at is

| (2.4) |

The set of selected variables is . As long as in (2.1) exists, it can be shown that the FDR associated with is guaranteed to be .

2.1 Variants of knockoff

The idea of knockoff provides a general framework for FDR control. It consists of three key components, as summarized below:

-

(a)

A ranking algorithm, which takes and an arbitrary design and assigns an importance metric to each variable in the design. In (2.2), it uses a particular ranking algorithm based on the solution path of Lasso.

-

(b)

An augmented design, which is the matrix , where a knockoff is created for each original . We supply the augmented design to the ranking algorithm to get importance metrics and for each variable and its knockoff.

-

(c)

A symmetric statistic , which combines the two importance metrics and to an ultimate importance metric for variable .

The choice of each component is non-unique. For (c), can be any anti-symmetric function. Two popular choices are the signed maximum statistic and the difference statistic:

| (2.5) |

For (b), the freedom comes from choosing and constructing . In fact, once is given, it can be shown that any satisfying (2.1) yields the same asymptotic performance for knockoff. Hence, the choice of the augmented design boils down to choosing . A popular option is the SDP-knockoff, which solves from a semi-definite programming:

| (2.6) |

Another option is the CI-knockoff (Liu and Rigollet, 2019):

| (2.7) |

For (a), Lasso is currently used as the ranking algorithm (see (2.2)), but it can be replaced by other linear regression methods. Take the least-squares for example. We can define a ranking algorithm that outputs as the importance metric. If we supply the augmented design to this ranking algorithm, then we have

| (2.8) |

We can set and and plug them into (2.3).

In summary, the flexibility of the three components gives rise to many different variants of knockoff. For example, we can use (2.2) or (2.8) as the ranking algorithm, (2.6) or (2.7) as the augmented design, and either one in (2.5) as the symmetric statistic; this already gives variants of knockoff. By the theory in Barber and Candès (2015), each variant guarantees the finite-sample FDR control. When the FDR is under control, the user always wants to select as many true signals as possible, i.e., to maximize the power. In this paper, one of our goals is to understand and compare the power of different variants of knockoff.

To this end, we start from the default choices of the three components in the orthodox knockoff, where the ranking algorithm is Lasso as in (2.2), the augmented design is the SDP-knockoff as in (2.6), and the symmetric statistic is the signed maximum in (2.5). In Sections 4-6, we successively alter each component and study its impact on the power.

2.2 Prototypes of knockoff

Given a variant of knockoff (where a specific choice of the ranking algorithm is applied to the augmented design ), we define the corresponding prototype method as follows: It runs the same ranking algorithm on the original design matrix , and outputs as importance metrics. The method selects variables by thresholding at , where

| (2.9) |

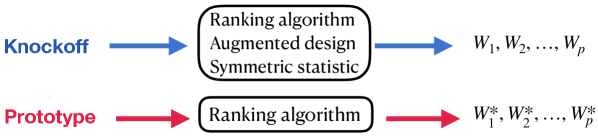

Compared with knockoff, the prototype ranks variables by , whose induced ranking may be different from the one by . Additionally, the prototype has access to an ideal threshold that guarantees an exact FDR control but is practically infeasible. In contrast, knockoff has to find a data-driven threshold from (2.4). See Figure 1.

We look at two examples. Consider the orthodox knockoff, where the ranking algorithm is Lasso (see (2.2)). Its prototype runs Lasso on to get and assigns an importance metric to variable as

| (2.10) |

It then selects variables by thresholding using the ideal threshold in (2.9). We call this method the Lasso-path. It is the prototype of all the variants of knockoff that use Lasso as ranking algorithm. For all variants of knockoff that use least-squares (see (2.8)) as the ranking algorithm, they share the same prototype, which computes and assigns an importance metric to variable as

| (2.11) |

It then selects variables by thresholding using the ideal threshold in (2.9). We call this method the least-squares.

In this paper, besides comparing different variants of knockoff, we also aim to compare each variant with its prototype. Here is the motivation: FDR control splits into two tasks: (1) ranking the importance of variables and (2) finding a data-driven threshold. When the FDR is under control, the power depends on how well Task 1 is performed. Importantly, in knockoff, although the augmented design and the ranking algorithm are meant to carry Task 2 only, they do affect the final ranking of variables because the ranking by ’s is usually different from the ranking by ’s. This yields a potential power loss compared with its prototype – a price we pay for finding a data-driven threshold. Hence, a power comparison between knockoff and its prototype helps us understand how large this price is.

Remark 1. In this paper, we focus on two ranking algorithms, Lasso-path and least-squares. They are both tuning-free. When the ranking algorithm has tuning parameters, we should not set the tuning parameters in the prototype the same as in the original knockoff. For example, we can use to rank variables, treating as a tuning parameter. The prototype runs lasso on the original design with variables, while knockoff runs lasso on the augmented design with variables. The optimal that minimizes the expected Hamming error is different in the two scenarios. A reasonable approach of comparing knockoff and its prototype is to use their respective optimal . This will require computing the expected Hamming error of lasso for an arbitrary (Ji and Jin, 2012; Ke and Wang, 2021).

3 Rare/Weak signal model and criteria of power comparison

We introduce our theoretical framework of power comparison. Recall that we consider a linear model , where , , and . Without loss of generality, fix . Given , we allow to be any integer such that . This is from the requirement of knockoff (it needs to guarantee the existence of in (2.1)) and should not be viewed as a limitation of our theory. Our results are extendable to , provided that knockoff is replaced by its extension in this case (see Section 9 for a discussion). The Gram matrix is

| (3.1) |

We adopt the Rare/Weak signal model (Donoho and Jin, 2004) to assume that satisfies:

| (3.2) |

where denotes a point mass at . Here, is the expected fraction of signals, and is the signal strength. We let be the driving asymptotic parameter and tie with through fixed constants and :

| (3.3) |

The parameters, and , characterize the signal rarity and the signal strength, respectively. Here, does not appear in the order of nonzero , because we have already re-parameterized such that the diagonals of are (see Footnote 1).

Under the Rare/Weak signal model (3.2)-(3.3), we define two diagrams for characterizing the power of knockoff. Let be the ultimate importance metric (2.3) assigned to variable , and consider the set of selected variables at a threshold :

Let . Define , , and , where the expectation is taken with respect to the randomness of both and . Write , and define

The first quantity is the expected Hamming error. The last two quantities are proxies of the false discovery rate and true positive rate, respectively.222The we consider here is the ratio of expectations of false positives and total discoveries (called mFDR in some literature), not the original definition of FDR, which is the expectation of ratios of false positives and total discoveries. According to Javanmard and Montanari (2018), mFDR and FDR can be different in situations with high variability, but it is not the case here. In our setting, the expectation of total discoveries grows to infinity as a power of , hence, mFDR and FDR have a negligible difference.

The following definition is conventional in the study of Rare/Weak signal models (Genovese et al., 2012; Ji and Jin, 2012) and will be used frequently in our theoretical results:

Definition 3.1 (Multi- term)

Consider a sequence . If for any fixed , and , we call a multi- term and write ( is a generic notion for all multi- terms). If there is a constant such that , we write , which means for any fixed , and .

In the Rare/Weak signal model, for many classes of designs of interest, and satisfy a property: There exist two fixed functions and such that, for any , as ,

| (3.4) |

The two functions and depend on the choice of the three components in knockoff and the design class. We propose the FDR-TPR trade-off diagram as follows:

Definition 3.2 (FDR-TPR trade-off diagram)

Given a variant of knockoff and a sequence of designs indexed by , if and satisfy (3.4), the FDR-TPR trade-off diagram associated with is the plot with in the y-axis and in the x-axis, as varies.

An FDR-TPR trade-off diagram depends on . To compare the performance of two variants of knockoff, we have to draw many curves for different values of . Hence, we introduce another diagram, which characterizes the power simultaneously at all . Define . This is the minimum expected Hamming selection error when the threshold is chosen optimally. For each variant of knockoff and each class of designs of interest, there exists a bivariate function such that

| (3.5) |

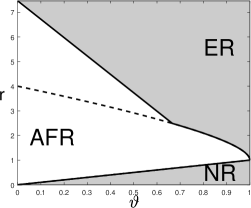

The phase diagram is defined as follows:

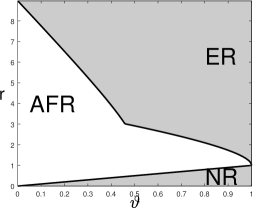

Definition 3.3 (Phase diagram)

When satisfies (3.5), the phase diagram is defined to the partition of the two-dimensional space into three regions:

-

•

Region of Exact Recovery (ER): .

-

•

Region of Almost Full Recovery (AFR): .

-

•

Region of No Recovery (NR): .

The curves separating different regions are called phase curves. We use to denote the curve between NR and AFR, and the curve between AFR and ER.

In the ER region, the expected Hamming error, , tends to zero. Therefore, with high probability, the support of is exactly recovered. In the AFR region, does not tend to zero but is much smaller than (which is the expected number of signals). As a result, with high probability, the majority of signals are correctly recovered. In the region of NR, is comparable with the number of signals, and variable selection fails. The phase diagram was introduced in the literature (Genovese et al., 2012; Ji and Jin, 2012) but has never been used to study FDR control methods.

We illustrate these definitions with an example. Both the FDR-TPR trade-off diagram and phase diagram only depend on the importance metrics assigned to variables. Therefore, they are also well-defined for the prototypes in Section 2.2. We consider a special class of designs, where , and a prototype that assigns the importance metrics

| (3.6) |

The next proposition is adapted from literature (Donoho and Jin, 2004; Ji and Jin, 2012) and proved in the Appendix. We use to denote , for any .

Proposition 3.1

Suppose and consider the importance metric in (3.6). When , the FDR-TPR trade-off diagram is given by and . The phase diagram is given by and .

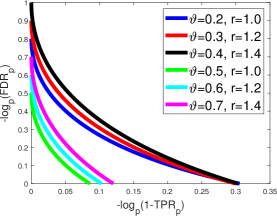

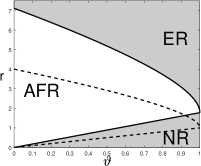

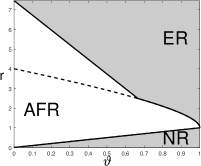

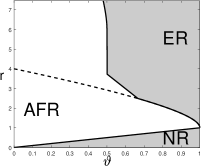

These diagrams are visualized in Figure 2.

As we have mentioned in Section 2.2, FDR control is composed of the task of ranking variables and the task of finding a data-driven threshold. It is the variable ranking that determines the power of an FDR control method simultaneously at all FDR levels . The two diagrams in Definitions 3.2-3.3 only depend on the importance metrics assigned to variables, hence, they measure the quality of variable ranking, which is fundamental for power comparison of different FDR control methods when they all control FDR at the same level.

4 Impact of the symmetric statistic

We fix the choice of ranking algorithm and augmented design in the orthodox knockoff and compare using the two symmetric statistics in (2.5). For simplicity, we consider the orthogonal design where . In this special case, the ranking algorithm in (2.2) reduces to calculating marginal regression coefficients and the output and reduce to

| (4.1) |

In the augmented design, the choice of in (2.6) reduces to . We consider a slightly more general form:

| (4.2) |

Given , the construction of is not unique, but all constructions lead to exactly the same FDR-TPR trade-off diagram and the same phase diagram. For this reason, we only specify as in (4.2), but not the actual . Fixing the above choices (4.1)-(4.2), we consider the two symmetric statistics in (2.5), which lead to the importance metrics of

| (4.3) |

We call the two variants of knockoff knockoff-sgm and knockoff-diff, respectively. The next theorem gives the explicit forms of and associated with these two variants. Its proof can be found in the Appendix.

Theorem 4.1

Consider a linear regression model where (3.1)-(3.3) hold. Suppose and . We construct in knockoff as in (4.2), for a constant , and let and be as in (4.1). For any constant , let and be the expected numbers of false positives and false negatives, by selecting variables with . When is the signed maximum statistic in (4.3), as ,

When is the difference statistic in (4.3), as ,

Here, is the generic multi- notion in Definition 3.1. For Theorem 4.1, using Mills’ ration, we actually know that . For other theorems, we do not always know the exact order of , but we can intuitively regard it as a polynomial of .

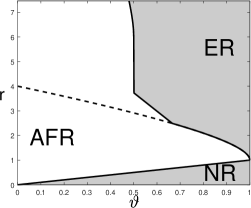

Given Theorem 4.1 and Definitions 3.2-3.3, we can derive the explicit FDR-TPR tradeoff diagrams and the phase diagrams:

Corollary 4.1

In the setting of Theorem 4.1, when , the FDR-TPR trade-off diagram is given by

The phase diagram is given by

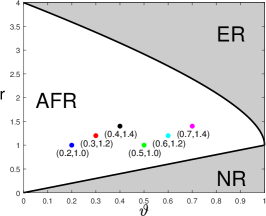

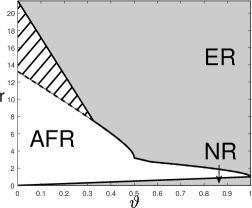

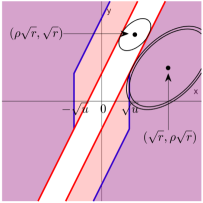

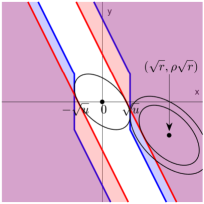

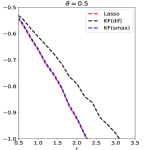

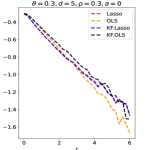

For both knockoff-sgm and knockoff-diff, by Corollary 4.1, the best choice of is . In the remaining of this section, we fix . Figure 3 gives visualizations of the FDR-TPR trade-off diagrams and phase diagrams. The prototype is Lasso-path (see (2.10)). In the orthogonal design , Lasso-path reduces to the prototype in (3.6), whose FDR-TPR trade-off diagram and phase diagram are given in Figure 2.

Comparison of two symmetric statistics:

First, we compare the phase diagrams in Figures 2-3 and find that (i) knockoff-sgm has a strictly better phase diagram than knockoff-diff, and (ii) knockoff-sgm has the same phase diagram as the prototype. It suggests that signed maximum is a better choice of symmetric statistic. It also suggests that knockoff-sgm yields a negligible power loss relative to its prototype.

We also point out that knockoff-sgm is already “optimal” among all symmetric statistics, in this orthogonal design. The reason is that, when , the Hamming error () has an information-theoretical lower bound (Genovese et al., 2012; Ji and Jin, 2012), whose induced phase diagram coincides with the phase diagram of the prototype, which is also the phase diagram of knockoff-sgm. This is the optimal phase diagram any method can achieve (including all variants of knockoff with other symmetric statistics).

Next, we compare the FDR-TPR trade-off diagrams of knockoff and the prototype. We focus on knockoff-sgm, whose trade-off diagram is in Figure 3 (right panel). The trade-off diagram of the prototype is in Figure 2 (right panel). We find that the trade-off diagram of knockoff-sgm is slightly different from the one of the prototype. By Theorem 4.1, ; hence, the FDR-TRP trade-off curve is truncated at in the x-axis. For large , the curve hits zero before the x-axis reaches , and the truncation has no impact. However, for small , the curve has changed due to the truncation (Figure 3, right panel, all but the blue curve).

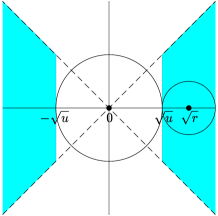

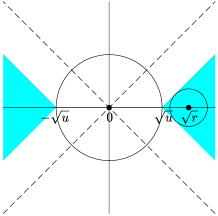

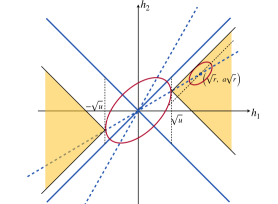

Some geometric insights, especially why signed maximum is “optimal”.

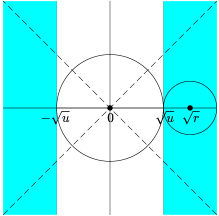

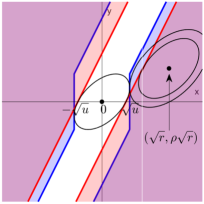

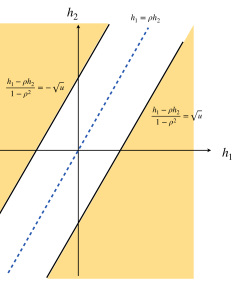

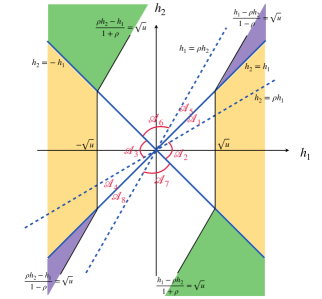

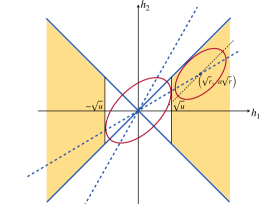

By (4.1) and (4.3), the importance metrics produced by knockoff can be written as , where and are the th variable and its knockoff, and is a bivariate function depending on the choice of symmetric statistic. Define the “rejection region” as

Figure 4 shows the rejection region induced by knockoff-sgm, knockoff-diff, and their prototype. Write and . The random vector follows the bivariate normal distribution with covariance matrix . Its mean vector is when and when . By Lemma 7.1 (to be introduced in Section 7), the exponent in is determined by the Euclidean distance from to and the exponent in is determined by the Euclidean distance from to . From Figure 4, it is clear that the difference statistic is inferior to the signed maximum statistic because the distance from to is strictly smaller in the former.

As we have mentioned earlier, signed maximum is “optimal” among all symmetric statistics, because its phase diagram already matches with the information-theoretic lower bound. Now, we use Figure 4 to provide a geometric interpretation of why signed maximum is “optimal”. We call a subset an eligible rejection region if there exists a symmetric statistic whose induced rejection region is . It is not hard to see that any eligible should be symmetric with respect to both x-axis and y-axis. In addition, by the anti-symmetry requirement , an eligible rejection region also needs to satisfy the following necessary condition: , where is the reflection of with respect to the line . The prototype has the optimal phase diagram, but its rejection region (Figure 4, right panel) does not satisfy this condition. We can see that the rejection region of knockoff-sgm (left panel) is a minimal modification of to tailor to this condition. This partially explains why signed maximum is already the best choice in this setting.

Remark 2. We consider a non-stochastic threshold in Theorem 4.1. For a data-driven threshold , if there is such that with probability , then Theorem 4.1 continues to hold.

Remark 3. In this section, we conduct power comparison only on the orthogonal design. Our rationale is as follows: A good method has to at least perform well in the simplest case. If a method is inferior to others in the orthogonal design, then we do not expect it to have a good potential in real applications where the designs can be much more complicated, i.e., the results on orthogonal designs help us filter out those methods that have little potential in practice. Such insights are valuable to users.

Remark 4. Recently, Weinstein et al. (2021) showed a remarkable result: Under linear sparsity and random Gaussian design, they found that knockoff with the difference symmetric statistic has great power. We note that the prototype of their knockoff is thresholded Lasso, not Lasso, and so the gain of power is primarily from prototype instead of symmetric statistic. Also, see Ke and Wang (2021) for a comparison of thresholded-Lasso v.s. Lasso.

5 Impact of the augmented design

We fix the choice of ranking algorithm and symmetric statistic as in the orthodox knockoff and compare using two augmented designs, the SDP-knockoff in (2.6) and the CI-knockoff in (2.7). We also call the two respective variants of knockoff the SDP-knockoff and CI-knockoff, so that “SDP-knockoff” (say) has two meanings, an augmented design or a variant of knockoff, depending on the context.

When , SDP-knockoff and CI-knockoff are the same and reduce to , so it is impossible to tell their difference in power. We must consider non-orthogonal designs. However, since there is no explicit form of the Lasso solution path, the results for a general are difficult to obtain; despite technical challenges, the phase diagrams may be too messy to provide any useful insight. We hope to find a class of non-orthogonal designs such that (i) it is mathematically tractable, (ii) it is considerably different from the orthogonal design and allows to have some “large” off-diagonal entries, and (iii) it captures some key features of real applications. We start from a class of row-wise sparse designs, which approximate the designs in many real applications (e.g., in bioinformatics and in compressed sensing). The next proposition is adapted from Lemma 1 of Jin et al. (2014), whose proof is omitted.

Proposition 5.1

Consider a linear model where (3.1)-(3.3) hold. Suppose each row of has at most nonzero entries, where is a multi- term as in Definition 3.1. Let be the support of . There exists a constant integer such that with probability , is a blockwise diagonal matrix afte a permutation of indices, and the maximum block size is bounded by .

Proposition 5.1 is a consequence of the interplay between design sparsity and signal sparsity: Under the Rare/Weak signal model (3.2) and a sparse design, the true signals in appear in groups, where each group contains only a small number of variables and distinct groups are mutually uncorrelated. This motivates us to consider a simpler setting where is blockwise diagonal by itself. While these two settings look so different from each other, the asymptotic behavior of Hamming error is closely related. For example, when is a tridiagonal matrix with equal values in the sub-diagonal, the optimal phase diagram is the same as in the case where is blockwise diagonal with blocks (Ji and Jin, 2012; Jin et al., 2014). Inspired by these observations, we study a class of blockwise diagonal designs (Jin and Ke, 2016): For some and a permutation matrix ,

| (5.1) |

This design serves the aforementioned purposes (i)-(iii): It has only one parameter , so is mathematically tractable. The nonzero off-diagonal entries of are at the constant order, so this design is sufficiently different from the orthogonal design (in contrast, many literature consider the independent random Gaussian design, for which the maximum absolute off-diagonal entry of is only ). Also, as we have argued above, studying this design helps us draw useful insights that will likely continue to hold for general sparse designs.

5.1 The prototype, Lasso-path

Before studying SDP-knockoff and CI-knockoff, we first study their prototype, Lasso-path. The next theorem characterizes and for Lasso-path and is proved in the Appendix.

Theorem 5.1

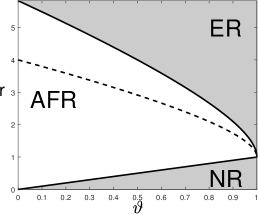

Using Theorem 5.1, we can deduce the FDR-TPR tradeoff diagram and phase diagram. To save space, we only present the phase diagram:

Corollary 5.1 (Phase diagram of Lasso-path)

A visualization of the phase diagram for is in Figure 5.

When , the blockwise diagonal design reduces to the orthogonal design, Lasso-path reduces to (3.6), and the phase diagram reduces to the one in Proposition 3.1. Comparing Figure 5 with Figure 2, the phase diagram of Lasso-path is inferior to the one for orthogonal designs. This suggests that the strength of design correlations can have a significant impact on the performance of variable selection.

Another observation from Figure 5 is that the sign of plays a crucial role. This is related to the “signal cancellation” phenomenon (Ke et al., 2014; Ke and Yang, 2017). Suppose is a block and both and are signals. It is seen that , whose absolute value is strictly smaller than for a negative . Hence, when is negative, the signal at creates a “cancellation effect” and makes marginally less correlated with . Lasso is known to be quite vulnerable to “signal cancellation” (Zhao and Yu, 2006). This is why the phase diagram becomes worse when the sign of is flipped. We will provide a more rigorous explanation in Section 7 using geometric properties of the Lasso solution.

5.2 SDP-knockoff

We now study the SDP-knockoff, where is as in (2.6). For the block-wise diagonal design parameterized by , we have an explicit form of :

| (5.2) |

The value of controls the correlation between and . SDP-knockoff aims to minimize this correlation, subject to the eligibility constraints. We first study the case .

Theorem 5.2 (The case of )

Consider a linear model where (3.1)-(3.3) hold. Suppose and is as in (5.1), where . We construct in knockoff with as in (5.2). Let , and be as in (2.2)-(2.3), where is the signed maximum in (2.5). For any constant , let and be the expected numbers of false positives and false negatives, by selecting variables with . As ,

and for ,

and for ,

where , , and .

When , listing the separate forms of and is tedious. We instead present the form of , which is sufficient for deriving the phase diagram.

Theorem 5.3 (The case of )

Consider a linear model where (3.1)-(3.3) hold. Suppose and is as in (5.1), where . We construct in knockoff with as in (5.2). Let , and be as in (2.2)-(2.3), where is the signed maximum in (2.5). For any constant , let and be the expected numbers of false positives and false negatives, by selecting variables with . As ,

where

and , are the same as those in Theorem 5.2.

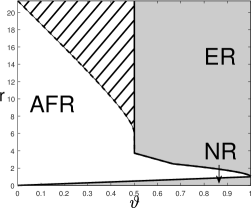

Corollary 5.2 (Phase diagram of SDP-knockoff)

A visualization of the phase diagram for three values of is in Figure 6.

Comparing Corollary 5.2 and Corollary 5.1, We have the following observations:

-

•

When , SDP-knockoff shares the same phase diagram as Lasso-path, i.e., SDP-knockoff yields a negligible power loss compared with its prototype.

-

•

When , the phase diagrams of SDP-knockoff is inferior to that of Lasso-path. Especially, when , the AFR region of SDP-knockoff is infinite: For any , no matter how large is, SDP-knockoff never achieves Exact Recovery.

We give an explanation of the discrepancy of the phase diagram between SDP-knockoff and Lasso-path for . First, consider . By (5.2), and . It follows that the th knockoff is uncorrelated with the th original variable. However, this knockoff is still highly correlated with the th original variable. Suppose is a true signal variable. Then, a true signal at will increase the absolute correlation between and but decrease the absolute correlation between and (since ), making it more difficult for to stand out. Next, consider . Suppose has two ‘nested’ signals, i.e., . By (5.2) and an elementary calculation,

When , variable and its knockoff have the same absolute correlation with . Consequently, there is a non-diminishing probability that the true signal variable fails to dominate its knockoff variable, making it impossible to select consistently. In the Rare/Weak signal model, ‘nested’ signals appear with a non-diminishing probability if . This explains why when and .

The rationale of SDP-knockoff is to minimize the correlation between a variable and its own knockoff, but this is not necessarily the best strategy for constructing knockoff variables when the original variables are highly correlated. In the next subsection, we will see that a proper increase of the correlation between a variable and its knockoff can boost power.

5.3 CI-knockoff

We study the CI-knockoff, where is as in (2.7). Liu and Rigollet (2019) showed that when in (2.7), the resulting satisfies , where is the projection matrix to the linear span of . It means and are conditionally uncorrelated, conditioning on the other original variables. For the block-wise diagonal design (5.1), has an explicit form:

| (5.3) |

Compared with (5.1), the value of has changed. We recall that controls the correlation between an original variable and its knockoff. In SDP-knockoff, is chosen as the minimum eligible value, but in CI-knockoff, is set at .

Theorem 5.4

Consider a linear model where (3.1)-(3.3) hold. Suppose and is as in (5.1), with a correlation parameter . We construct in knockoff with as in (5.3). Let , and be as in (2.2)-(2.3), where is the signed maximum in (2.5). For any constant , let and be the expected numbers of false positives and false negatives, by selecting variables with . As ,

where is the same as that in Theorem 5.3.

The exponent in Theorem 5.4 is in fact the same as that in Theorem 5.1. We immediately conclude that CI-knockoff yields the same phase diagram as its prototype, Lasso-path.

Corollary 5.3 (Phase diagram of CI-knockoff)

The result of CI-knockoff is very encouraging. We now explain how CI-knockoff improves SDP-knockoff for . Comparing (5.3) with (5.2), we find that the correlation between and increases from to . We revisit the scenario of two ‘nested’ signals, i.e., . By direct calculations,

It always holds that . As long as is sufficiently large, the original variable can standard out. This resolves the previous issue of SDP-knockoff.

Going beyond the block-wise design, it is an interesting question whether CI-knockoff still improves SDP-knockoff. We study it numerically in Section 8, where we consider designs such as Factor models, Exponential decay, and Normalized Wishart; see Experiment 4.

Remark 5. Our theory is focused on the blockwise design in (5.1). Using similar techniques, we can study other blockwise designs, such as blocks or varying-size blocks. Take blocks for example. In knockoff, solving Lasso in (2.2) reduces to solving many -dimensional problems separately. Let ++- be a block. The sufficient statistic for is . By Lemma 7.1, the Hamming error at depends on the interplay between probability contour of and geometry of the -dimensional Lasso problem. We make such analysis for in the proofs of Theorems 5.2-5.4, which can be extended to a general .

6 Impact of the ranking algorithm

We consider two options of the ranking algorithm, Lasso and least-squares. As the ranking algorithm changes, the prototype is different. In Section 6.1, we first compare two prototypes. In Section 6.2, we further compare the associated versions of knockoff.

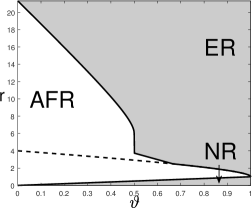

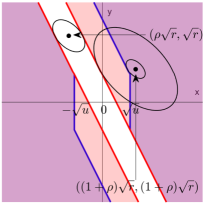

In the orthodox knockoff, ranking algorithm is Lasso, augmented design is SDP-knockoff, and symmetric statistic is signed maximum. We re-name it SDP-knockoff-Lasso. If ranking algorithm is changed to least-squares (with the other two components unchanged), we call it SDP-knockoff-OLS. In each method, if augmented design is changed to CI-knockoff (with the other two components unchanged), we call them CI-knockoff-Lasso and CI-knockoff-OLS, respectively. SDP-knockoff-Lasso, CI-knockoff-Lasso, and their prototype, Lasso-path, have been studied in Section 5. In this section, we study SDP-knockoff-OLS, CI-knockoff-OLS, and their prototype, least-squares, and compare the results with those in Section 5.

We consider the general design, where can be any positive definite matrix. We then restrict ourselves to the special case of blockwise design in (5.1). The reason we can study general designs is that the least-squares solution has a simple and explicit form (but the Lasso solution does not).

6.1 The prototype, least-squares

Before studying SDP-knockoff-OLS and CI-knockoff-OLS, we first study their common prototype, the least-squares (see (2.11)).

Theorem 6.1

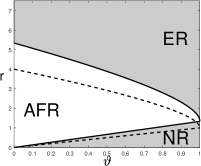

Corollary 6.1 (Phase diagram of OLS)

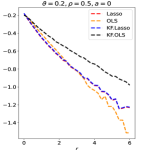

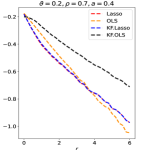

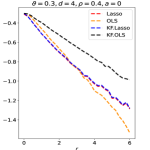

Figure 7 (left panel) shows the phase diagram of least-squares for ; as a reference, in the right two panels, we plot again the phase diagrams of Lasso-path for . For the comparison between least-squares and Lasso-path, we have the following observations:

-

•

In terms of , Lasso-path is always better than least-squares. To attain Almost Full Recovery, Lasso-path requires , but least-squares requires .

-

•

In terms of , Lasso-path is better than least-squares when is relatively large (i.e., is comparably sparser), and least-squares is better than Lasso-path when is relatively small (i.e., is comparably denser).

-

•

The sign of also matters. For small , the advantage of least-squares over Lasso-path on is much more obvious when is negative.

We give an intuitive explanation to the above phenomena. We say a signal variable (i.e., ) is ‘isolated’ if it is the only signal variable in the block, and we say two signals are ‘nested’ if they are in the same block. In the sparser regime (i.e., is large), least-squares has a disadvantage because it is inefficient in discovering an ‘isolated’ signal. In the less sparse regime (i.e., is small), Lasso-path has a disadvantage because it suffers from signal cancellation when estimating a pair of ‘nested’ signals (‘signal cancellation’ means a signal variable has a weak marginal correlation with due to the effect of other signals correlated with this one). A more rigorous explanation is given in Section 7, using geometry of solutions of least-squares and Lasso; see Lemma 7.2, Figure 8, and discussions therein.

6.2 Knockoff-OLS

We now study SDP-knockoff-OLS and CI-knockoff-OLS. The next theorem provides a general result that applies to all augmented designs:

Theorem 6.2

Consider a linear model where (3.1)-(3.3) hold. Suppose . We construct in knockoff as in (2.1), with some choice of . Write . Suppose is chosen such that is non-singular. Let be the submatrix of restricted to the th and th rows and columns. Denote and . Suppose , for a constanat . Let , and be as in (2.8) and (2.3), where is the signed maximum in (2.5). For any constant , let and be the expected numbers of false positives and false negatives, by selecting variables with . As ,

The phase diagram of knockoff-OLS is governed by the quantities . We now consider the special case of the blockwise design in (5.1), where the augmented design is such that , where in SDP-knockoff and in CI-knockoff. We note that in SDP-knockoff, the matrix is singular when . In other words, SDP-knockoff-OLS is well defined only for .

Corollary 6.2 (Phase diagram of knockoff-OLS)

Figure 7 (second left panel) shows the phase diagram of CI-knockoff-OLS for . In this figure, the right two panels are the phase diagrams of CI-knockoff-Lasso for .

From Corollary 6.2 and Figure 7, we draw two conclusions: First, for both SDP-knockoff-OLS and and CI-knockoff-OLS, whenever , their phase diagrams are strictly inferior to the phase diagram of the least-squares (prototype). This is different from the case of using Lasso as ranking algorithm, where the phase diagrams of CI-knockoff-Lasso and Lasso-path (prototype) are the same in the blockwise design for all . Second, the comparison of CI-knockoff-OLS and CI-knockoff-Lasso is largely similar to the comparison between the least-squares and Lasso-path (see Section 6.1).

Remark 6. When we use the least-squares as the ranking algorithm, such a gap between knockoff and its prototype always exists, for a general design. To see this, note that by Theorem 6.1 and Theorem 6.2, the phase diagrams of knockoff-OLS and its prototype are governed by the quantities and , respectively. Since and are the th diagonal elements of and , respectively, and is a principal submatrix of , it follows by elementary linear algebra that is always true (and this inequality is often strict). Unfortunately, it is impossible to mitigate this gap by using the augmented design in (2.1), no matter how we choose . Xing et al. (2023) proposed a new idea of constructing an augmented design, called the Gaussian mirror, which is tailored to using the least-squares as the ranking algorithm. In a companion paper (Ke et al., 2022), we show that the Gaussian mirror attains the same phase diagram as the least-squares.

Remark 7. Besides Lasso and least-squares, we may consider other ranking algorithms, such as the thresholded Lasso, non-convex penalization methods, and the forward-backward selection. See Ke and Wang (2021) about the phase diagrams of these methods.

7 The proof ideas and some geometric insights

A key technical tool in the proof is the following lemma, which is proved in the Appendix. Recall that is a generic notation of multi- terms; see Definition 3.1. For a vector , denotes the -norm; for a matrix , denotes the spectral norm.

Lemma 7.1

Fix an integer , a vector , a covariance matrix , and an open set such that . The quantities do not change with . Suppose . Consider a sequence of random vectors , indexed by , satisfying that

where is a random vector and is a random covariance matrix. As , suppose for any fixed and , and . Then, as ,

or equivalently, and for any constant .

This lemma connects the rate of convergence of with the geometric property of the set . The exponent is the “radius” of the largest ellipsoid that centers at and is fully contained in the complement of .

Proof sketch.

We illustrate how to use Lemma 7.1 to prove the theorems in Sections 4-6. Take the proof of Theorem 5.1 for example. Consider the block-wise design in (5.1). Under this design, the objective of Lasso is separable, and it reduces to solving many 2-dimensional Lasso problems separably. Fix and suppose is a block. Let be as in (2.10). Write

| (7.1) |

Since the Lasso objective is separable, are purely determined by . Particularly, there exists , such that if and only if . We call the “rejection region” of Lasso-path. The probabilities of a false positive and a false negative occurring at are respectively

Conditioning on , the random vector has a bivariate normal distribution, whose mean is a constant vector and whose covariance matrix is , where is the same as in (5.1). Applying Lemma 7.1, we reduce the proof into two steps: In Step 1, we derive the rejection region . In Step 2, for each possible realization of with , we calculate , and for each possible realization of with , we calculate , where . Both steps can be carried out by direct calculations. We use a similar strategy to prove other theorems. The proof is sometimes complicated. For example, to analyze knockoff for block-wise diagonal designs, we have to consider the random vector . The proof requires deriving a 4-dimensional rejection region and calculating , for an arbitrary . The calculations are very tedious.

The geometric insight about two prototypes.

We use the geometric interpretation of our proofs to give more insights about Lasso-path versus least-squares (see Corollary 5.1 and Corollary 6.1). Under the blockwise design (5.1), for each method, the objective is separable, so that the event can be described via a 2-dimensional rejection region. The next lemma gives the rejection regions of Lasso-path and least-squares:

Lemma 7.2

These rejection regions are shown in Figure 8. Their geometric properties are different for positive and negative . Fix . Let be as in (7.1), and write .

-

•

The rate of convergence of is determined by the largest ellipsoid that centers at and is contained in . We call this ellipsoid the FP-ellipsoid.

-

•

The rate of convergence of is determined by the largest ellipsoid that centers at and is contained in . We call this ellipsoid the FN-ellipsoid.

By direct calculations, . Under our model, has 4 possible values , where the first two correspond to a null at and the last two correspond to a non-null at . The probability of having a selection error at thus splits into 4 terms, and which term is dominating depends on the values of and . The realization of that plays a dominating role is called the ‘most-likely’ case. For example, when is large (i.e., is sparser), the most-likely case of a false positive occuring at is when ; when is small (i.e., is less sparse), the most-likely case of a false positive is when . Table 1 summarizes the ‘most-likely’ cases. We also visualize the ‘most-likely’ cases for different in Figure 8. In each plot of Figure 8, we have coordinated the thresholds in two methods so that the FP-ellipsoid is exactly the same. It suffices to compare the FN-ellipsoid: The method with a larger FN-ellipsoid has a faster rate of convergence on the Hamming error. It is clear that, when is large, the FN-ellipsoid of Lasso-path is larger; when is small, the FN-ellipsoid of least-squares is larger. This explains the different performances of two methods. Moreover, when is small, comparing the case of a positive with the case of a negative , we find that the difference between FN-ellipsoids of two methods are much more prominent in the case of a negative . This explains why the sign of matters.

| Sparsity | Correlation | Error type | Most-likely case | Center of ellipsoid |

| large | positive/negative | FP | , | |

| FN | , | |||

| small | positive | FP | , | |

| FN | , | |||

| small | negative | FP | , | |

| FN | , |

8 Simulations

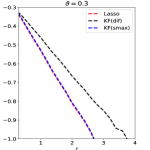

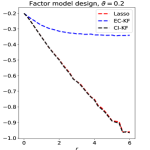

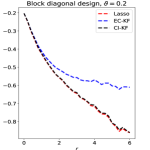

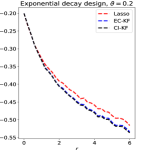

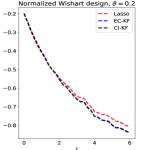

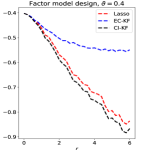

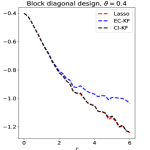

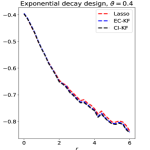

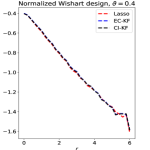

We use numerical experiments to support and exemplify the theoretical results in Sections 4-6. In Experiments 1 and 2, we consider orthogonal designs and block-wise diagonal designs, respectively. In Experiments 3 and 4, we consider other design classes, including block-wise diagonal designs with larger blocks, factor models, exponentially decaying designs, and normalized Wishart designs. We consider four methods, Lasso-path (Lasso), least-squares (OLS), knockoff with Lasso-path ranking (KF.Lasso) and with least-squares ranking (KF.OLS). We use either the signed maximum or the difference as the symmetric statistic, and for KF we choose , unless specified otherwise. It is called the equi-correlated knockoff (EC-KF), and is the same as the SDP-knockoff for orthogonal designs and the block-wise diagonal designs. In Experiments 1-3, this is the only we use, and so we write EC-KF as KF for short. In Experiments 4, we also consider the conditional independence knockoff (CI-KF). For most experiments, fixing a parameter setting, we generate data sets and record the averaged Hamming selection error among these 200 repetitions.

Experiment 1. We investigate the performance of different methods for orthogonal designs. Given , and ranging on a grid from to with step size , we generate data from where is an matrix with unit length columns that are orthogonal to each other and is generated from (3.2). We implemented Lasso and KF.Lasso using both the signed maximum and the difference as the symmetric statistic. Under the orthogonal design, Lasso and OLS yield the same importance metric thus OLS and KF.OLS are neglected in this experiment. Each method outputs importance statistics, and we threshold these importance statistics at where minimizes in theory. The results are in Figure 9, where the y-axis is , and is the averaged Hamming selection error over 200 repetitions.

The theory in Sections 4-5 suggests the following for orthogonal designs: (i) Regarding the choice of symmetric statistic for KF, the signed maximum outperforms the difference. (ii) With signed maximum as the symmetric statistic, KF.Lasso has a similar performance as Lasso. These theoretical results are perfectly validated by simulations (see Figure 9).

Experiment 2. We consider the block-wise diagonal design with blocks, where we take and . In the data generation, we fix an matrix such that has the desirable form. We then generate in the same way as before. For each , we fix , and let range on a grid from to with a step size . For KF.Lasso and KF.OLS, we now fix the symmetric statistic as signed maximum and the default choice of yields that with . In this case, is degenerated, thus an was subtracted from each elements of to ensure KF.OLS is applicable. The results are in the first two panels of Figure 10.

The theory in Section 5 suggests that since the two values of considered here are in , KF.Lasso has a similar performance as its prototype, Lasso. While according to Section 6, KF.OLS has a inferior performance comparing to its prototype, OLS. The simulation results are consistent with these theoretical predictions. Moreover, we can see that, for the current value, OLS has a smaller Hamming error than that of Lasso when is large, and the opposite is true when is small. These also agree with our theory.

Experiment 3. We further consider blockwise diagonal designs with larger-size blocks. Given and that is a multiple of , we generate such that is block-wise diagonal with diagonal blocks, where the off-diagonal elements of each block are all equal to . Other steps of the data generation are the same as in Experiment 2. We consider and . For each choice of , we set and let range on a grid from to with a step size . We use signed maximum as symmetric statistic in KF and use the equi-correlated knockoff described above. The results are in the last two panels of Figure 10.

One noteworthy observation is that KF.Lasso still has a similar performance as its own prototype. Meanwhile, KF.OLS can get close to its prototype in the case where is close to 0. Another observation is that OLS outperforms Lasso when is large, and Lasso slightly outperforms OLS when is small. While our theory is only derived for , the simulations suggest that similar insight continues to apply when the block size gets larger.

Experiment 4. In Section 5, we studied variants of knockoff with different augmented designs. The theory for block-wise designs suggests that using CI-knockoff to construct yields a higher power than using EC-knockoff (for block-wise design, EC-knockoff is the same as SDP-knockoff). In this experiment, we investigate whether using CI-knockoff still yields a power boost for other design classes. We consider 4 types of designs:

-

•

Factor models: , where is a matrix whose -th row is equal to with drawn from ;

-

•

Block diagonal: Same as in Experiment 2, where .

-

•

Exponential decay: The -th element of is , for .

-

•

Normalized Wishart: is the sample correlation matrix of samples of .

In the normalized Wishart design, the CI-knockoff in (2.7) may not satisfy . We modify it to , where is the maximum value in such that . For each design, we fix , let take values in and let range on a grid from to with a step size . Different from previous experiments, we generate from , for . The motivation of using this model is to allow for negative entries in . Even when contains only nonnegative elements, this signal model can still reveal the effect of having negative correlations in the design. We compare two versions of knockoff, EC-knockoff and CI-knockoff, along with the prototype, Lasso. The results are in Figure 11.

For the block-wise diagonal design, the simulations suggest that CI-KF significantly outperforms EC-KF, and that CI-KF has a similar performance as the prototype, Lasso. This is consistent with the theory in Section 5.2 and Section 5.3. CI-KF also yields a significant improvement over EC-KF in the factor design, and the two methods perform similarly in the exponentially decaying design and the normalized Wishart design. We notice that the Gram matrix of the normalized Wishart design has uniformly small off-diagonal entries for the current , which is similar to the orthogonal design and explains why EC-KF and CI-KF do not have much difference. Combining these simulation results, we recommend CI-KF for practical use. Additionally, in some settings (e.g., factor design, ; exponentially decaying design, ), CI-KF even outperforms its prototype Lasso. One possible reason is that the ideal threshold we use is derived by ignoring the multi- term, but this term can have a non-negligible effect for a moderately large , so the Hamming error of Lasso presented here may be larger than the actual optimal one.

9 Discussions

How to maximize the power when controlling FDR at a targeted level is a problem of great interest. We focus on the FDR control method, knockoff, and point out that it has three key components: ranking algorithm, augmented design, and symmetric statistic. Since each component admits multiple choices, knockoff has many different variants. All the variants guarantee finite-sample FDR control. Our goal is to understand which variants enjoy good power. In a Rare/Weak signal model, for each variant of knockoff under consideration, we derive explicit forms of false positive rate and false negative rate, and obtain the theoretical phase diagram. The results provide useful guidelines of choosing the version of knockoff to use in practice. We also define the prototype of knockoff, which uses only one component, ranking algorithm, and has access to an ideal threshold. We compare the phase diagram of knockoff with the phase diagram of prototype. The results help us understand the extra price we pay for finding a data-driven threshold to control FDR.

We have several notable discoveries: (i) For the choice of symmetric statistic, signed maximum is better than difference, because the latter has an inferior phase diagram in the orthogonal design. (ii) For the choice of augmented design, CI-knockoff is better than SDP-knockoff, because the latter has an inferior phase diagram in a simple blockwise diagonal design. (ii) For the choice of ranking algorithm, roughly, Lasso is better than least-squares when the signals are extremely sparse and the design correlations are moderate; and least-squares is better than Lasso when the signals are only moderately sparse and the design correlations are more severe. (iv) In a simple blockwise diagonal design, when knockoff uses Lasso as ranking algorithm, with proper choices of two other components, knockoff has the same phase diagram as its prototype (i.e., we pay a negligible price for finding a data-driven threshold). This is however not true when knockoff uses least-squares as ranking algorithm.

There are several directions to extend our current results. First, we focus on the regime where FDR and TPR converge to either 0 or 1 and characterize the rates of convergence. The more subtle regime where FDR and TPR converge to constants between 0 and 1 is not studied. We leave it to future work. Second, the study of knockoff here is only for block-wise diagonal designs. For general designs, it is very tedious to derive the precise phase diagram, but some cruder results may be less tedious to derive, such as an upper bound for the Hamming error. This kind of results will help shed more insights on how to construct the knockoff variables (e.g., how to choose ). Third, we only investigate Lasso-path or the least-squares as options of the ranking algorithm. It is interesting to study the power of FDR control methods based on other ranking algorithms, such as the marginal screening and iterative sure screening (Fan and Lv, 2008) and the covariance assisted screening (Ke et al., 2014; Ke and Yang, 2017). The covariance assisted screening was shown to yield optimal phase diagrams for a broad class of sparse designs; whether it can be developed into an FDR control method with “optimal” power remains unknown and is worth future study. Last, some FDR control methods may not fit exactly the unified framework here. For instance, the multiple data splits (Dai et al., 2022) is a method that controls FDR through data splitting. We can similarly assess its power using the Rare/Weak signal model and phase diagram, except that we need to assume the rows of are generated. We leave such study to future work.

Acknowledgments and Disclosure of Funding

The research of Jun S. Liu was partially supported by the NSF grant DMS-201541 and the NIH R01grant HG011485-01. The research of Zheng T. Ke was partially supported by the NSF CAREER grant DMS-1943902.

Appendix A Proof of Lemma 7.1

By definition of the multi- term, it suffices to show that, for every , as ,

| (A.1) |

We introduce two sets and such that

Define for any . By definition, . As a result, for all . Define

| (A.2) |

Then, . Furthermore, since is a quadratic function and , given any , there exists such that

| (A.3) |

Note that (A.3) guarantees that is bounded. For any and ,

where and are positive constants that only depend on . It follows that there exists a constant such that

| (A.4) |

Additionally, since is an open set and , there exists , such that

Define

| (A.5) |

It is easy to see that . Additionally, in light of (A.3) and (A.4),

| (A.6) |

Since , to show (A.1), it suffices to show that

| (A.7) |

and

| (A.8) |

First, we show (A.7). Let denote the density of . Write . It is seen that

| (A.9) |

By direct calculations,

| (A.10) | ||||

| (A.11) |

The assumptions on imply that, for any constant ,

Let be the event that and , for some to be decided. On this event, for any ,

where and are positive constants that do not depend on , and in the last line we have used the fact that is a bounded set so that is bounded. It follows that we can choose an appropriately small such that

| (A.12) |

Combining (A.12) with (A.6) gives

Moreover, since is a ball with radius ,

where is the unit ball in , whose volume is a constant. We plug the above results into (A.10) and notice that on the event , for a constant . It yields that, when satisfies the event ,

| (A.13) |

for some constant . It follows that

We plug it into the left hand side of (A.7) and note that as . This gives the desirable claim in (A.7).

Next, we show (A.8). We define a counterpart of the set by

Define . Then, and

The distribution of is a distribution, which does not depend on . We have

| (A.14) | ||||

| (A.15) | ||||

| (A.16) |

For chi-square distribution, the tail probability has an explicit form:

where is the upper incomplete gamma function and is the ordinary gamma function. By property of the upper incomplete gamma function, as . It follows that

In particular, when is sufficiently large, the left hand side is . We plug these results into (A.14) to get

| (A.17) |

It remains to study the difference caused by replacing by . Let

Then,

| (A.18) |

Similar to (A.10), we have

| (A.19) | ||||

| (A.20) |

For a constant to be decided, let be the event that

| (A.21) |

On this event, we study both and . Re-write

By definition, , and . On the event , for any ,

for a constant that does not depend on . Choosing , we have for all . Additionally, by definition, for all . Combining the above gives

Recall that is the unit ball in . It follows immediately that

| (A.22) |

At the same time, for any , on the event ,

where is a constant that does not depend on and in the last line we have used the fact that for . We choose properly small so that . It follows that

| (A.23) |

Additionally, the definition of already guarantees that for all . Consequently,

| (A.24) |

We plug (A.22) and (A.24) into (A.19). It yields that, on the event ,

| (A.25) |

for a constant . Then,

By our assumption, for any and , and . In particular, we can choose . It gives

We combine the above results and plug them into (A.18). It follows that

| (A.26) |

Combining (A.17) and (A.26) gives

This gives the claim in (A.8). The proof of this lemma is complete.

Appendix B Proof of Lemma 7.2

First, we study the least-squares. Note that has an explicit solution: . Since is a block-wise diagonal matrix, we immediately have

Recall that . Then, if and only if

It immediately gives the rejection region for least-squares.

Next, we study the Lasso-path. We write as for notation simplicity. The lasso estimate minimizes the objective

When is a block-wise diagonal matrix, the objective is separable, and we can optimize over each pair of separately. It reduces to solving many bi-variate problems:

| (B.1) |

Write and let

Then, the optimization (B.1) can be written as

| (B.2) |

Recall that is the value of at which becomes nonzero for the first time. Our goal is to find a region of such that .

It suffices to consider the case of . To see this, we consider changing to in the matrix . The objective remains unchanged if we also change to and to . Note that the change of to has no impact on ; this means is unchanged if we simultaneously flip the sign of and . Consequently, once we know the rejection region for , we can immediately obtain that for by a reflection of the region with respect to the x-axis.

Below, we fix . We first derive the explicit form of the whole solution path and then use it to decide the rejection region. Taking sub-gradients of (B.1), we find that has to satisfy

| (B.3) |

where if , if , and can be equal to any value in if . Let be the values at which variables enter the solution path. When , and . Plugging them into (B.3) gives . The definition of implies that , for any . We then have . Similarly, it is true that . It gives

| (B.4) |

We first assume . By (B.3) and continuity of solution path, there exists a sufficiently small constant such that, for , the following equation holds.

| (B.5) |

The sign vector of for has four different cases: , , , . For these four different cases, we can use (B.5) to solve . The solutions in four cases are respectively

The solution has to match the sign assumption on . For each of the four cases, the requirement becomes

-

•

Case 1: , .

-

•

Case 2: , .

-

•

Case 3: , .

-

•

Case 4: , .

Note that we have assumed . Then, Case is possible only in the region , where

In each case, . To get the value of , we use the continuity of the solution path. It implies that at . As a result, the value of in Case is

| (B.6) |

It is easy to verify that in each case. We also need to check that in the region , the KKT condition (B.3) can be satisfied with for all . For example, in Case 1, (B.3) becomes

We can solve the equations to get and . It can be verified that for and . The verification for other cases is similar and thus omitted. We then assume . By symmetry, we will have the same result, except that are switched in the expression of and . This gives the other four cases:

In these four cases, we similarly have and

| (B.7) |

These eight regions are shown in Figure 12.

We then compute and the associated rejection region. Note that in Case 1-Case 4, and in Case 5-Case 8. It follows directly that

| (B.8) |

As a result, the region if and only if the vector is in the following set:

In Figure 12, the 3 subsets are colored by yellow, purple, and green, respectively. This gives the rejection region for Lasso-path.

Appendix C Proof of Theorem 4.1

By definition of and the Rare/Weak signal model (3.2)-(3.3), we have

| (C.1) |

where , , and . Therefore, it suffices to study and .

Fix . The knockoff filter applies Lasso to the design matrix . This design is belongs to the block-wise diagonal design (5.1) with a dimension and . The variable and its own knockoff are in one block. Fix and write

| (C.2) |

It is easy to see that follows a distribution when , and it follows a distribution , when , where

Let be the region of corresponding to the event that . It follows from Lemma 7.1 that

| (C.3) | ||||

| (C.4) |

Below, we first derive the rejection region , and then compute the exponents in (C.3).

Recall that and are the same as in (4.3). They are indeed the values of at which the variable and its knockoff enter the solution path of a bivariate lasso as in (B.1). We can apply the solution path derived in the proof of Lemma 7.2, with . Before we proceed to the proof, we argue that it suffices to consider the case of . If , we can simultaneously flip the signs of and , so that the objective (B.1) remains unchanged; as a result, the values of remain unchanged, so does the symmetric statistic . It implies that, if we flip the sign of , the rejection region is reflected with respect to the x-axis. At the same time, in light of the exponents in (C.3), we consider two ellipsoids

| (C.5) |

Similarly, if we simultaneously flip the signs of and , these ellipsoids remain unchanged. It implies that, if we flip the sign of , these ellipsoids are reflected with respect to the x-axis. Combining the above observations, we know that the exponents in (C.3) are unchanged with a sign flip of , i.e., they only depend on . We assume without loss of generality.

Fix . Write and . The symmetric statistics in (4.3) can be re-written as

Recall that and are as in (C.2). Let be the values of at which variables enter the solution path of a bivariate lasso. In the proof of Lemma 7.2, we have derived the formula of ; see (B.6) and (B.7) (with replaced by ). It follows that

where regions - are the same as those on the right panel of Figure 12 (with replaced by ). Plugging in (B.6) and (B.7) gives the following results:

-

•

Region : , , , .

-

•

Region : , , , .

-

•

Region : , , , .

-

•

Region : , , , .

-

•

Regions -: , , .

The event that corresponds to that is in the region of

| (C.6) | ||||

| (C.7) |

The event that corresponds to that is in the region of

| (C.8) | ||||

| (C.9) |

These two regions are shown in Figure 13.

We are now ready to compute the exponents in (C.3). First, we compute . Let be the same as in (C.5). Then,

When the rejection region is , from Figure 13, we can increase until intersects with the line of . For any on the surface of this ellipsoid, the perpendicular vector of its tangent plane is proportional to . When the ellipsoid intersects with the line of , the perpendicular vector should be proportional to . Therefore, we need to find such that

The second equation requires that . Combining it with the first equation gives . We then plug it into the second equation to obtain . This gives

| (C.10) |

When the rejection region is , there are 3 possible cases:

-

(i)

The ellipsoid intersects with the line ,

-

(ii)

The ellipsoid intersects with the line ,

-

(iii)

The ellipsoid intersects with the point .

In Case (i), we can compute the intersection point by solving for and . The second relationship gives . Together with the first relationship, we have . It is not in . Similarly, for Case (ii), we can show that the intersection point is , which is not in either. The only possible case is Case (iii), where the intersection point is and the associated . We have proved that

| (C.11) |

Next, we compute . Let be the same as in (C.5). Then,

Note that the center of the ellipsoid is . When either or , if and only if . In other words, the above is well defined only if . We now fix . When the rejection region is , the ellipsoid intersects with either the line of or the line of . Since the perpendicular vector of the tangent plane of the ellipsoid at is proportional to , we can solve the intersection points from

By calculations, the two intersection points are and . The associated value of is and , respectively. When we increase the ellipsoid until it interacts with , the corresponding is the smaller of the above two values. This gives

| (C.12) |

When the rejection region is , the ellipsoid intersects with either the line of or the line of . We can solve the intersection points from

Solving these equations gives the two intersection points: and . The corresponding value of is and , respectively. The smaller of these two values is . We have proved that

| (C.13) |

We plug (C.10)-(C.13) into (C.3), and we further plug it into (C.1). This gives the claim for . As we have argued, the results for only requires replacing by .

Appendix D Proof of Theorem 5.1

Without loss of generality, we assume is even. Then, for block-wise diagonal designs as in (5.1), the Lasso objective is separable. Therefore, for each , it is not affected by any outside the block. Additionally, by symmetry, the distribution of is the same for all . It follows that

| (D.1) | ||||

| (D.2) |

where can be odd index. Similarly, we can derive that

| (D.3) | ||||

| (D.4) |

Fix variables , and consider the random vector . Then,

The vector is equal to

| (D.5) |

in the four cases where is , , , and , respectively. Let be the rejection region induced by Lasso-path, given explicitly in Lemma 7.2. By Lemma 7.1, the probabilities in (D.1) and (D.3) are related to the following quantities:

and plug it into (D.1) and (D.3). It gives

| (D.6) |

It remains to compute the exponents -.

First, we consider the case that . The rejection region in Figure 12 is defined by the following lines:

-

•

Line 1: .

-

•

Line 2: .

-

•

Line 3: .

-

•

Line 4: .

-

•

Line 5: .

-

•

Line 6: .

Consider a general ellipsoid:

Given any line , as increases, this ellipsoid eventually intersects with this line. The intersection point is computed by the following equations:

The second equation (it is indeed a linear equation on ) says that the perpendicular vector of the tangent plane is orthogonal to the line. Solving the above equations gives the intersection point and the value of : As long as , we have

| (D.7) |

Using the expressions of lines 1-6, we can obtain the corresponding for 6 lines:

We first look at the ellipsoid and study when it intersects with . Note that . The above values become

Therefore, as we increase , this ellipsoid first intersects with line 1 and line 4. For line 1, the intersection point is , but it is outside the rejection region (see Figure 12); the situation for line 4 is similar. We then further increase , and the ellipsoid intersects with line 2 and line 5, where the intersection point is ; this point is indeed on the boundary of the rejection region. We thus conclude that

| (D.8) |