[a]David Kim for the Prometheus authors

Prometheus: An Open-Source Neutrino Telescope Simulation

Abstract

The soon-to-be-realized, global network of neutrino telescopes will allow new opportunities for collaboration between detectors. While each detector is distinct, they share the same underlying physical processes and detection principles. The full simulation chain for these telescopes is typically proprietary which limits the opportunity for joint studies. This means there is no consistent framework for simulating multiple detectors. To overcome these challenges, we introduce Prometheus, an open-source simulation tool for neutrino telescopes. Prometheus simulates neutrino injection and final state and photon propagation in both ice and water. It also supports user-supplied injection and detector specifications. In this contribution, we will introduce the software; show its runtime performance; and highlight successes in reproducing simulation results from multiple ice- and water-based observatories.

1 Introduction

The global network of neutrino telescopes, defined as gigaton-scale neutrino detectors, has allowed us observe the Universe in new ways. The subset of this network of telescope deployed on ice or water includes the IceCube Neutrino Observatory [1] near the South Pole, proposed detectors ORCA and ARCA [2] in the Mediterranean Sea (KM3NeT collaboration), and Baikal-GVD in Lake Baikal, Russia [3] (BDUNT collaboration). Additionally, new experiments like P-ONE [4] off the coast of Vancouver and TRIDENT [5] in the South China Sea are underway, as well as an expansion for the IceCube Observatory [6, 7].

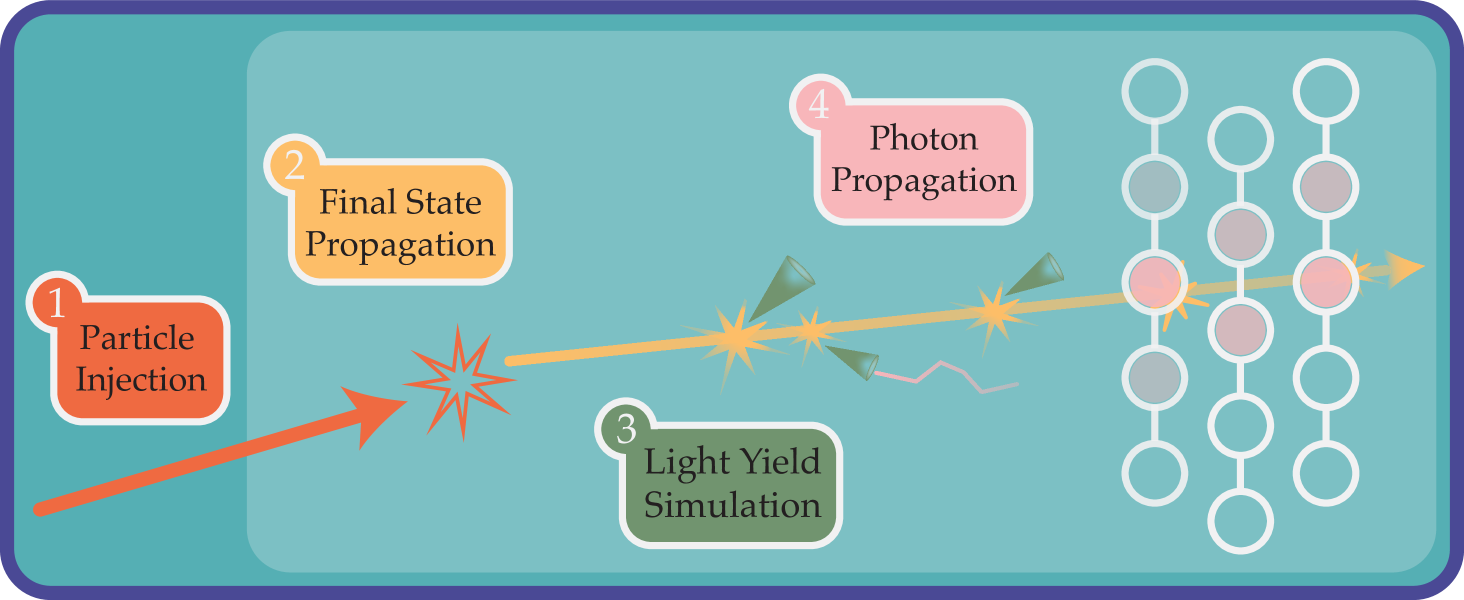

These telescopes all share many technological features. Each of these detectors operate by detecting Cherenkov photons emitted by neutrino interaction byproducts, and as such follow the same general simulation chain illustrated in Fig. 1. The only proprietary step is the final detector response, which occurs after an optical module (OM) has detected a photon. Yet for many years we have lacked a simulation framework that takes advantage of this similarity. Existing packages individually cover one or two of these common steps, but until now there has been no easy way to simulate a particle from injection to photon propagation.

Prometheus [8] looks to correct this by providing an integrated framework to simulate these common steps for arbitrary detectors in ice and water, using a combination of publicly available packages and those newly developed for this work. Neutrino injection is handled by LeptonInjector[9], an event generation recently developed by the IceCube Collaboration. Taus and muons are then propagated by PROPOSAL [10]. Light yield simulation and photon propagation in ice relies on PPC [11], while in water these steps are covered by Fennel [12] and Hyperion, respectively.

Prometheus’s flexibility allows one to optimize detector configurations for specific physics goals, while the common format allows one to develop reconstruction techniques that may be applied across different experiments. With the recent explosion in machine-learning research, it is now more important than ever that we are able to rapidly implement and test new ideas without relying on tools and data that may be proprietary to their experiments.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. In Sec. 2 we outline the format of Prometheus’s output and validate against published results. In Sec. 3 we present community work that employs Prometheus. In Sec. 4 we provide a short example running Prometheus code. Finally, in Sec. 5 we conclude and offer our future outlook.

2 Prometheus: Output and Validation

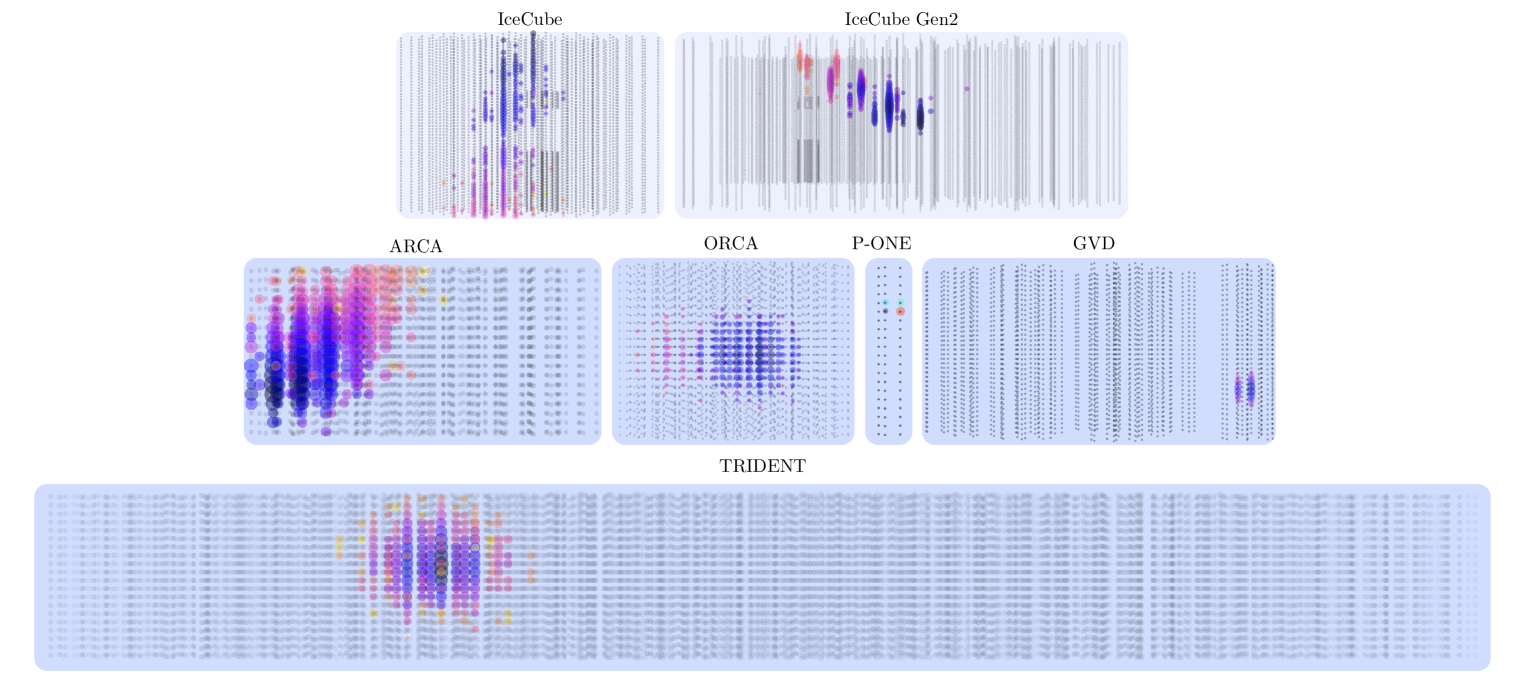

Prometheus outputs to Parquet [13] files that include two primary fields—photons and mc_truth. photons contains information on photons that produce hits in user-defined detection regions. This includes photon arrival time, OM identification numbers, OM position, and the final-state particle that produced the photon. Fig. 1 shows event displays for various detectors generated using the information in photons. mc_truth includes information on the injection like the interaction vertex; the initial neutrino type, energy, and direction; and the final state types, energies, directions, and parent particles. Users may also save the configuration file (see Sec. 4) as a json file. This allows the user to resimulate events using the same parameters, which is useful for comparing the same event across multiple detector geometries.

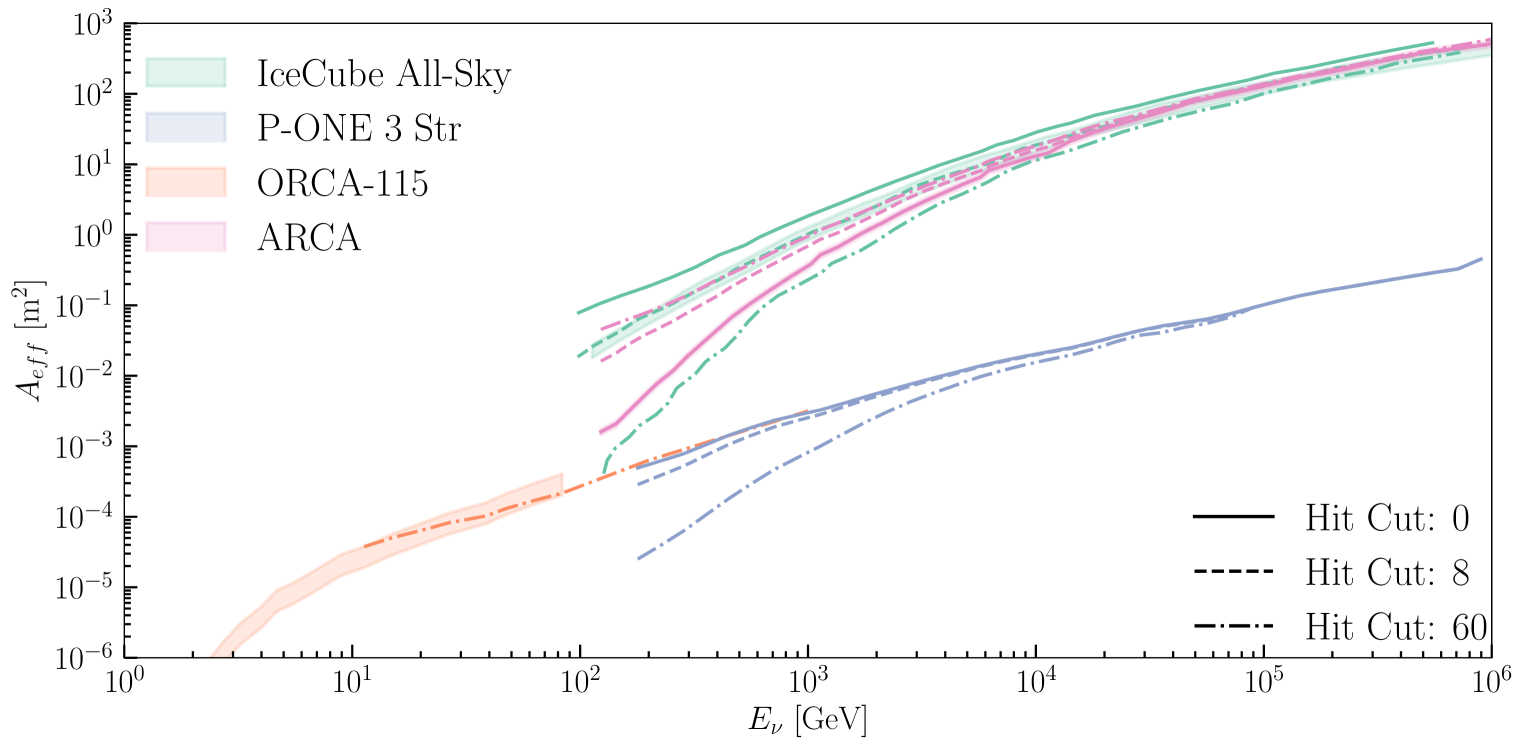

The information stored in mc_truth allows us to compute effective areas when combined with the weights from LeptonWeighter. Since it mainly depends on the physics implemented in Prometheus—such as neutrino-nucleon interactions, lepton range, and photon propagation—effective area serves as a reliable indicator of our code’s performance when all simulation steps are properly integrated. We can then validate our simulation by comparing these effective areas to published data. Fig. 3 compares different experiments published effective areas to our estimation using Prometheus simulations. It is worth noting that the calculations for effective area rely on detector-specific cuts and OM response, to which we have limited or no access. We can therefore expect differences of from these missing detector details.

3 Community Contributions

Developing a published reconstruction is often a long-term effort internal to an experiment, meaning methods are slow to implement and difficult to compare. Prometheus remedies this by allowing users to readily generate the large data sets necessary to test the feasibility and relative performance of different reconstruction methods. In this section we highlight two submissions at ICRC 2023 that utilize Prometheus in such a way. The first of these works is a software-focused effort that looks to improve the speed of first reconstructions at detectors and the second is a hardware-focused effort concerning GPU alternatives for low power computing.

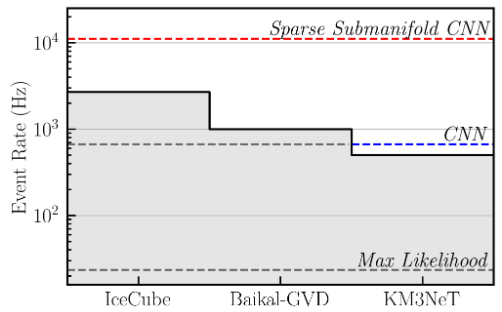

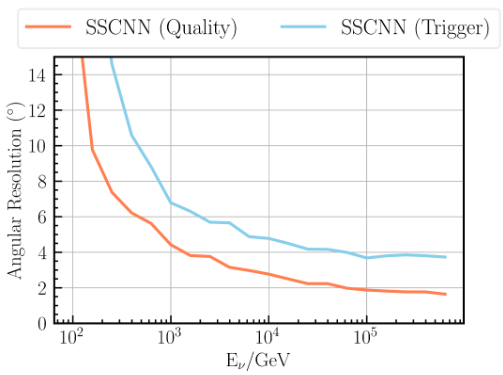

Ref. [20], proposes sparse-submanifold convolutions (SSCNNs) as an alternative to the convolutional neural network (CNN) and traditional trigger-level event reconstructions currently used in neutrino telescopes. Their directional and energy algorithm is trained on a data set of 412892 events and tested on a further 50000 events, cut from a set of 3 million generated by Prometheus. As seen in Fig. 4, the SSCNN is capable of running at speeds comparable to the neutrino telescope trigger rates. In Fig. 5, it achieves a median angular resolution below for the highest-energy trigger-level events, which matches or outperforms currently employed reconstructions. Their work could be applied to improve on-site reconstructions and filtering for notable events at any detector.

Ref. [21], is another Prometheus user submission that explores hardware accelerators to improving event reconstruction. Specifically, they look at how a Tensor Processing Unit (TPU) compatible algorithm could lower energy consumption while running comparable operations to the current GPU-based ones. Their model reaches a median angular resolution around above GeV. Meanwhile, approximate peak total power consumption drops from 100W on the best performing GPU (Apple M1 Pro chip) down to 3W on the Google Edge TPU. The portion of the power consumption directed to the ML accelerator component drops from 15W to 2W. This submission illustrates Prometheus’s utility in testing more speculative ideas and providing proof-of-concepts to encourage further work, particularly in the direction of machine learning.

The findings of both works are generic to any ice or water neutrino telescope. Their models are trained and tested on example detector geometries rather than the geometry of any existing or proposed detector. Since Prometheus is fully open-source, we hope it will facilitate not only easier iteration on these techniques but also greater collaboration in sharing and adapting them.

4 Examples

In this section we will walk through producing a simulation of charged-current interactions in an ice-based detector. This example will use mostly default values for injection parameters to show the essential steps in running a simulation, after which we will show how the user can set these parameters.

In this example, we set the number of events to simulate, the detector geometry file, and—using the final state particles—the event type. With just this, we can simulate events with Prometheus!

As briefly shown here, the config dictionary is our primary interface for configuring Prometheus. Key parameters not shown here include the output directory; random state seed; and injection parameters like injection angle and energy. Information on a detector’s medium, either ice or water, is stored in its geometry file. The geofiles directory in the GitHub repository has geometry files for all of the detectors in Fig. 2. Again, this only scratches the surface of Prometheus’s capabilities. For a more thorough description of all the options and features available see Ref. [8], which has more in-depth examples for charged-current events in ice and neutral-current events in water as well as directions on constructing a detector, weighting events, and getting event rates.

5 Conclusion

In this submission we have introduced Prometheus as an open-source software package for simulating neutrino telescopes. We have provided a brief example for simulating events in an ice-based detector and highlighted two current works that employ Prometheus. Prometheus’s flexibility of input for detector geometry and injection parameters allows it to handle simulation for the full range of existing and proposed telescopes in both water and ice.

As we have demonstrated in the highlighted community contributions, Prometheus facilitates the implementation of new ideas without the need for proprietary data, or for data on a scale not yet available. Via its particular application to machine-learning models, Prometheus can be a key piece in accelerating the development of faster, more efficient reconstructions for all detectors.

Finally, it is our hope that Prometheus opens the door for greater collaboration within the community. By encouraging the sharing of methods and simulated data sets, we hope work done by any one effort more quickly and easily becomes progress for every group in the global neutrino telescope network.

6 Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all users who tested early versions of this software, including—in no particular order—Miaochen Jin, Eliot Genton, Tong Zhu, Rasmus Ørsøe, Savanna Coffel, and Felix Yu. The authors that developed Prometheus were supported by Faculty of Arts and Sciences of Harvard University, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, NSF under grants PLR-1600823, PHY-1607644, Wisconsin Research Council with funds granted by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, Australian Government through the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme (project DP220101727), and Lynne Sacks and Paul Kim.

References

- [1] IceCube Collaboration, M. G. Aartsen et al. JINST 12 no. 03, (2017) P03012.

- [2] KM3Net Collaboration, S. Adrian-Martinez et al. J. Phys. G 43 no. 8, (2016) 084001.

- [3] A. D. Avrorin et al. Phys. Part. Nucl. 46 no. 2, (2015) 211–221.

- [4] P-ONE Collaboration, M. Agostini et al. Nature Astron. 4 no. 10, (2020) 913–915.

- [5] Z. P. Ye et al. arXiv:2207.04519.

- [6] IceCube Collaboration, A. Ishihara PoS ICRC2019 (2021) 1031.

- [7] IceCube-Gen2 Collaboration, M. G. Aartsen et al. J. Phys. G 48 no. 6, (2021) 060501.

- [8] J. Lazar, S. Meighen-Berger, C. Haack, D. Kim, S. Giner, and C. A. Argüelles.

- [9] IceCube Collaboration, R. Abbasi et al. Comput. Phys. Commun. 266 (2021) 108018.

- [10] J. H. Koehne, K. Frantzen, M. Schmitz, T. Fuchs, W. Rhode, D. Chirkin, and J. Becker Tjus Comput. Phys. Commun. 184 (2013) 2070–2090.

- [11] D. Chirkin, “ppc.” https://github.com/icecube/ppc, 2022.

- [12] S. Meighen-Berger, “Fennel: Light from tracks and cascades,” 2022. https://github.com/MeighenBergerS/fennel.

- [13] “Documentation | Apache Parquet.” https://parquet.apache.org/docs/. Accessed: 20123-02-17.

- [14] IceCube Collaboration, A. Karle PoS ICRC2009 (2010) .

- [15] KM3NeT Collaboration, G. de Wasseige, A. Kouchner, M. Colomer Molla, D. Dornic, and S. Hallmann PoS ICRC2019 (2020) 934.

- [16] IceCube, MAGIC, VERITAS Collaboration, M. G. Aartsen et al. JINST 11 no. 11, (2016) P11009.

- [17] B. Bakker, Trigger studies for the Antares and KM3NeT neutrino telescopes. PhD thesis, University of Amsterdam, 2011.

- [18] A. Avrorin et al. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 639 no. 1, (2011) 30–32. Proceedings of the Seventh International Workshop on Ring Imaging Cherenkov Detectors.

- [19] M. Hünnefeld, Online Reconstruction of Muon-Neutrino Events in IceCube using Deep Learning Techniques. PhD thesis, Technische Universität Dortmund, 2017.

- [20] F. J. Yu, J. Lazar, and C. A. Argüelles PoS ICRC2023 1004.

- [21] M. Jin, Y. Hu, and C. A. Argüelles.