Proposing Hierarchical Goal-Conditioned Policy Planning

in Multi-Goal Reinforcement Learning

††thanks: This is the preprint version of the paper accepted at ICAART 2025.

Abstract

Humanoid robots must master numerous tasks with sparse rewards, posing a challenge for reinforcement learning (RL). We propose a method combining RL and automated planning to address this. Our approach uses short goal-conditioned policies (GCPs) organized hierarchically, with Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) planning using high-level actions (HLAs). Instead of primitive actions, the planning process generates HLAs. A single plan-tree, maintained during the agent’s lifetime, holds knowledge about goal achievement. This hierarchy enhances sample efficiency and speeds up reasoning by reusing HLAs and anticipating future actions. Our Hierarchical Goal-Conditioned Policy Planning (HGCPP) framework uniquely integrates GCPs, MCTS, and hierarchical RL, potentially improving exploration and planning in complex tasks.

1 INTRODUCTION

Humanoid robots have to learn to perform several, if not hundreds of tasks. For instance, a single robot working in a house will be expected to pack and unpack the dishwasher, pack and unpack the washing machine, make tea and coffee, fetch items on demand, tidy up a room, etc. For a reinforcement learning (RL) agent to discover good policies or action sequences when the tasks produce relatively sparse rewards is challenging (Pertsch et al.,, 2020; Ecoffet et al.,, 2021; Shin and Kim,, 2023; Hu et al.,, 2023; Li et al.,, 2023). Except for (Ecoffet et al.,, 2021), the other four references use hierarchical approaches. This paper proposes an approach for agents to learn multiple tasks (goals) drawing from techniques in hierarchical RL and automated planning.

A high-level description of our approach follows. The agent learns short goal-conditioned policies which are organized into a hierarchical structure. Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) is then used to plan to complete all the tasks. Typical actions in MCTS are replaced by high-level actions (HLAs) from the hierarchical structure. The lowest-level kind of HLA is a goal-conditioned policy (GCP). Higher-level HLAs are composed of lower-level HLAs. Actions in our version of MCTS can be any HLAs at any level. We assume that the primitive actions making up GCPs are given/known. But the planning process does not operate directly on primitive actions; it involves generating HLAs during planning.

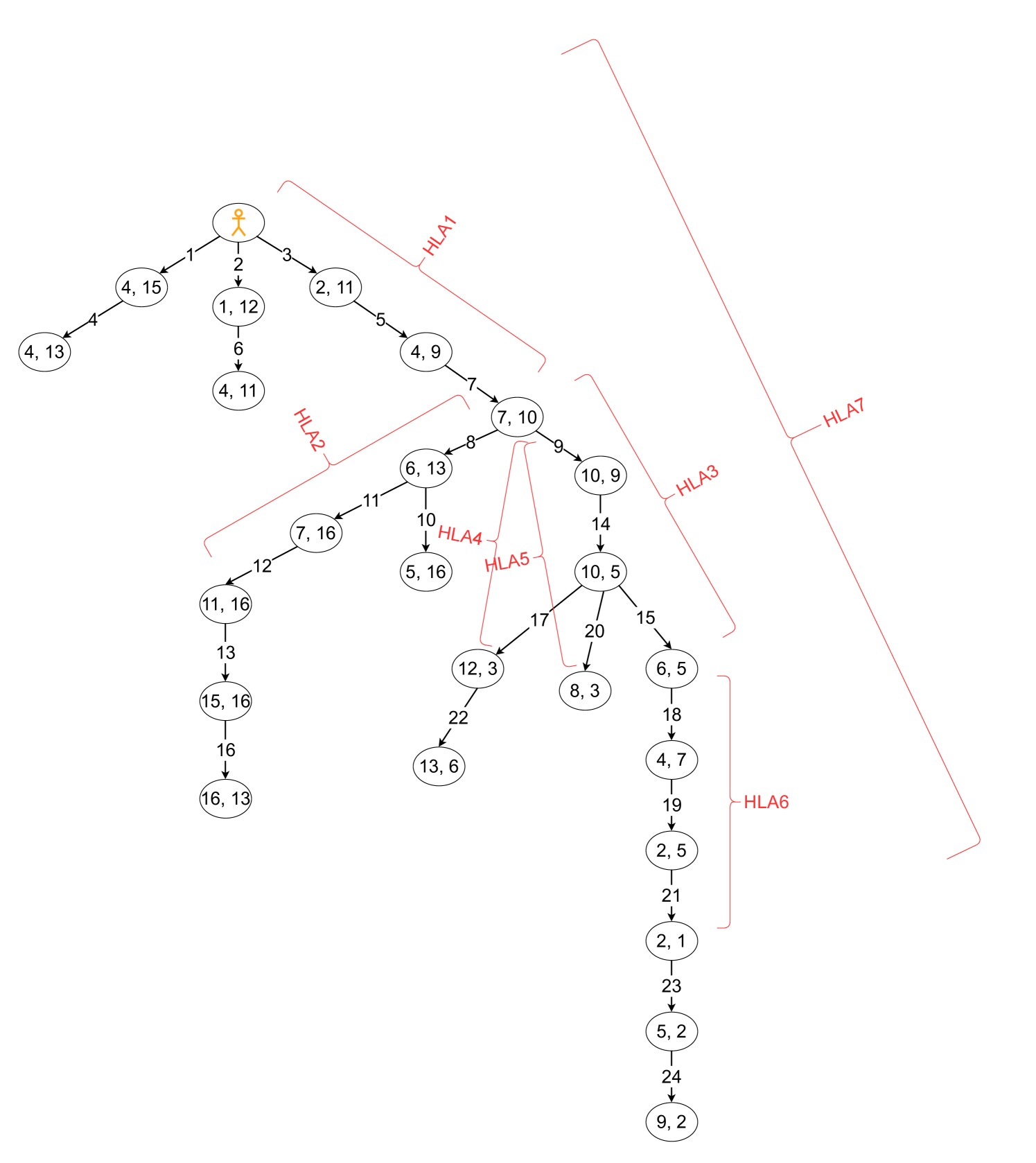

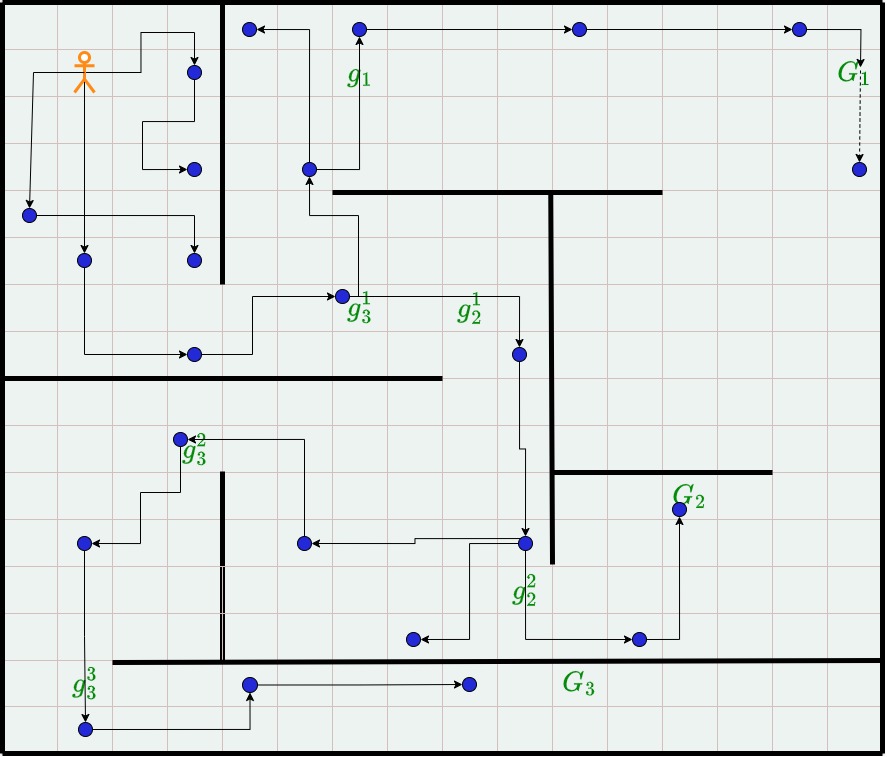

A single plan-tree is grown and maintained during the lifetime of the agent. The tree constitutes the agent’s knowledge about how to achieve its goals (how to complete its tasks). Figure 1 is a complete plan-tree for the environment depicted in Figure 2. The idea is to associate a value for each goal with every HLA (at every level) discovered by the agent so far. An agent becomes more sample efficient by reusing some of the same HLAs for reaching different goals. Moreover, the agent can reason (search) faster by looking farther into the future to find more valuable sequences of actions than if it considered only primitive actions. This is the conventional reason for employing hierarchical planning; see the papers referenced in Section 2.2 and Section 3

For ease of reference, we call our new approach HGCPP (Hierarchical Goal-Conditioned Policy Planning). To the best of our knowledge, at the time of writing, no-one has explicitly combined goal-conditioned policies, MCTS, and hierarchical RL in a single framework. This combination could potentially lead to more efficient exploration and planning in complex domains with multiple long-horizon goals.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides the necessary background theory. Section 3 reviews the related work. Section 4 presents our framework (or family of algorithms). We also propose some novel and existing techniques that could be used for implementing an instance of HGCPP. In Section 5 we further analyze our proposed approach and make further suggestions to improve it. As this is early-stage research, there is no evaluation yet.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Goal-Conditioned Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning (RL) is based on the Markov decision process (MDP). An MDP is described as a tuple , where is a set of states, is a set of (primitive) actions, is a transition function (the probability of reaching a state from a state via an action), and is the discount factor. The value of a state is the expected total discounted reward an agent will get from onward, that is,

where is the state reached by executing action in state . Similarly, the value of executing in is defined by

We call it the Q function and its value is a q-value. The aim in MDPs and RL is to maximize for all reachable states . A policy tells the agent what to do: execute when in . A policy can be defined in terms of a Q function:

It is thus desirable to find ‘good’ q-values (see later).

Goal-conditioned reinforcement learning (GCRL) (Schaul et al.,, 2015; Liu et al.,, 2022) is based on the GCMDP, defined as the tuple , where , , and are as before, is a set of (desired) goals and is goal-conditioned reward function. In GCRL, the value of a state and the Q function are conditioned on a goal : , respectively, . A goal-conditioned policy is

such that is the action to execute in state towards achieving .

2.2 Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning

Traditionally, hierarchical RL (HRL) has been a divide-and-conquer approach, that is, determine the end-goal, divide it into a set of subgoals, then select or learn the best way to reach the subgoals, and finally, achieve each subgoal in an order appropriate to reach the end-goal.

“Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning (HRL) rests on finding good re-usable temporally extended actions that may also provide opportunities for state abstraction. Methods for reinforcement learning can be extended to work with abstract states and actions over a hierarchy of subtasks that decompose the original problem, potentially reducing its computational complexity.” (Hengst,, 2012)

“The hierarchical approach has three challenges [619, 435]: find subgoals, find a meta-policy over these subgoals, and find subpolicies for these subgoals.” (Plaat,, 2023)

The divide-and-conquer approach can be thought of as a top-down approach. The approach that our framework takes is bottom-up: the agent learns ‘skills’ that could be employed for achieving different end-goals, then memorizes sets of connected skills as more complex skills. Even more complex skills may be memorized based on less complex skills, and so on. Higher-level skills are always based on already-learned skills. In this work, we call a skill (of any complexity) a high-level action.

2.3 Monte Carlo Tree Search

The version Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS) we are interested in is applicable to single agents based on MDPs (Kocsis and Szepesvari,, 2006).

An MCTS-based agent in state that wants to select its next action loops thru four phases to generate a search tree rooted at a node representing . Once the agent’s planning budget is depleted, it selects the action extending from the root that was most visited (see below) or has the highest q-value. While there still is planning budget, the algorithm loops thru the following phases (Browne et al.,, 2012).

Selection A route from the root until a leaf node is chosen.111For discrete problems with not ‘too many’ actions, a node is a leaf if not all actions have been tried at least once in that node. Let denote any variant of the Upper Confidence Bound, like UCB1 (Kocsis and Szepesvari,, 2006). For every non-leaf node in the tree, follow the path via action .

Expansion When a leaf node is encountered, select an action not yet tried in and generate a new node representing as child of .

Rollout To estimate a value for (or representing it), simulate one or more Monte Carlo trajectories (rollouts) and use them to calculate a reward-to-go from . If the rollout value for is , the can be calculated.

Backpropagation If has just been created and the q-value associated with the action leading to it has been determined, then all action branches on the path from the root till must be updated. That is, the change in value at the end of a path must be propagated bach up the tree.

In this paper, when we write (where might have indices and is some function), we generally mean and , where is the state represented by node .

2.4 Multi-Objective/Goal Reinforcement Learning

We make a distinction between multi-objective RL (MORL) and multi-goal RL (MGRL). MORL (Liu et al.,, 2015) attempts to achieve all goals simultaneously. There is often a weight or priority assigned to goals. MGRL (Kaelbling,, 1993; Sutton et al.,, 2011) does not weight any goal as more or less important and each goal is assumed to eventually be pursued individually. There is no question about which goal is more important; the agent simply pursues the goal it is commanded to. In both cases, the agent can learn all goals simultaneously (broadly speaking). When MORL goals are prioritized and MGRL has a curriculum, the two frameworks become very similar.

Our framework follows the MGRL approach, not the MORL approach.

3 RELATED WORK

The areas of hierarchical reinforcement learning (HRL) and goal-conditioned reinforcement learning (GCRL) are very large. The overlapping area of goal-conditioned hierarchical RL is also quite large. Table 1 shows where some of the related work falls with respect to the dimensions of 1) goal-conditioned (GC), 2) hierarchical (H), 3) planning (P) and 4) RL.

| only RL | RL+P | only P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| only GC | 12, 3, 25, 22, 2, 6 | 4, 15 | |

| GC+H | 9, 17, 10, 18, 19, 20 | 1, 5, 11, 13, 14, 16, 23, 24, 26, HGCPP | 7, 21 |

| only H | 8 |

| 1 (Kulkarni et al.,, 2016) 2 (Andrychowicz et al.,, 2017) 3 (Florensa et al.,, 2018) 4 (Nasiriany et al.,, 2019) 5 (Pinto and Coutinho,, 2019) 6 (Fang et al.,, 2019) 7 (Pertsch et al.,, 2020) 8 (Lu et al.,, 2020) 9 (Castanet et al.,, 2023) 10 (Kim et al.,, 2021) 11 (W ohlke et al.,, 2021) 12 (Ecoffet et al.,, 2021) 13 (Fang et al.,, 2022) | 14 (Li et al.,, 2022) 15 (Mezghani et al.,, 2022) 16 (Yang et al.,, 2022) 17 (Park et al.,, 2023) 18 (Shin and Kim,, 2023) 19 (Zadem et al.,, 2023) 20 (Hu et al.,, 2023) 21 (Li et al.,, 2023) 22 (Castanet et al.,, 2023) 23 (Wang et al., 2024b, ) 24 (Luo et al.,, 2024) 25 (Wang et al., 2024a, ) 26 (Bortkiewicz et al.,, 2024) |

We do not have the space for a full literature survey of work involving all combinations of two or more of these four dimensions. Nonetheless, we believe that the work mentioned in this section is fairly representative of the state of the art relating to HGCPP.

We found only two papers involving hierarchical MCTS: (Lu et al.,, 2020) does not involve RL nor goal-conditioning, nor multiple-goals. It is placed in the bottom right-hand corner of Table 1.

The work of Pinto and Coutinho, (2019) is the closest to our framework. They proposes a method for HRL in fighting games using options with MCTS. Instead of using all possible game actions, they create subsets of actions (options) for specific gameplay behaviors. Each option limits MCTS to search only relevant actions, making the search more efficient and precise. Options can be activated from any state and terminate after one step, allowing the agent to learn when to use and switch between different options. The approach uses Q-learning with linear regression to approximate option values, and an -greedy policy for option selection. They call their approach hierarchical simply because it uses options. HGCPP has hierarchies of arbitrary depth, whereas theirs is flat. They do not generate subgoals, while HGCPP generates reachable and novel behavioral goals to promote exploration. One could view their approach as being implicitly multi-goal. Pinto and Coutinho, (2019) is in the group together with HGCPP in Table 1.

4 THE PROPOSED ALGORITHM

We first give an overview, then give the pseudo-code. Then we discuss the novel and unconventional concepts in more detail.

We make two assumptions–that

-

•

the agent will always start a task from a specific, pre-defined state (location, battery-level, etc.) and

-

•

the agent may be given some subgoals to assist it in learning how to complete a task.

Future work could investigate methods to deal with task environments where these assumptions are relaxed.

We define a contextual goal-conditioned policy (CGCP) as a policy parameterized by a context and a (behavioral) goal , where is the state-space. The context gives the region from which the goal will be pursued. In this paper, we simplify the discussion by equating with one state and by equating with one state . A CGCP is something between an option (Sutton et al.,, 1999) and a GCP. Formally,

is a CGCP. The idea is that can be used to guide an agent from to . Whereas GCPs in traditional GCRL do not specify a context, we include it so that one can reason about all policies relevant to a given context. In the rest of this paper we refer to CGCPs simply as GCPs.

Two GCPs, as predecessor and as successor, are linked if and only if . When and , then we require that for and to be linked. We represent that is linked to as .

Assume that the agent has already generated some/many HLAs during MCTS. Let denote the set of all HLAs generated so far. They are organized in a tree structure (which we shall call a plan-tree). Each HLA can be decomposed into several lower-level HLAs, unless the HLA is a GCP. To indicate the start and end states of an HLA , we write . “Assume .” is redd ‘Assume is an HLA starting in state and ending in state ’. Notation refers to all HLAs starting in state , or refers to all HLAs starting in node (leading to children of ).

The exploration-exploitation strategy is determined by a function . is the value of a (learned) GCP . Every time a new GCP is leanrt, all non-GCP HLAs on the path from the root node to the GCP must be updated. This happens after/due to the backpropagation of to all linked GCPs on the path from the root.

If GCP is the parent of GCP in the plan-tree, then . Suppose is an HLA of node in the plan-tree (s.t. ), then there should exist a node which is a child of such that . If , then it means that is an HLA of node such that . We define linked GCPs of arbitrary length as

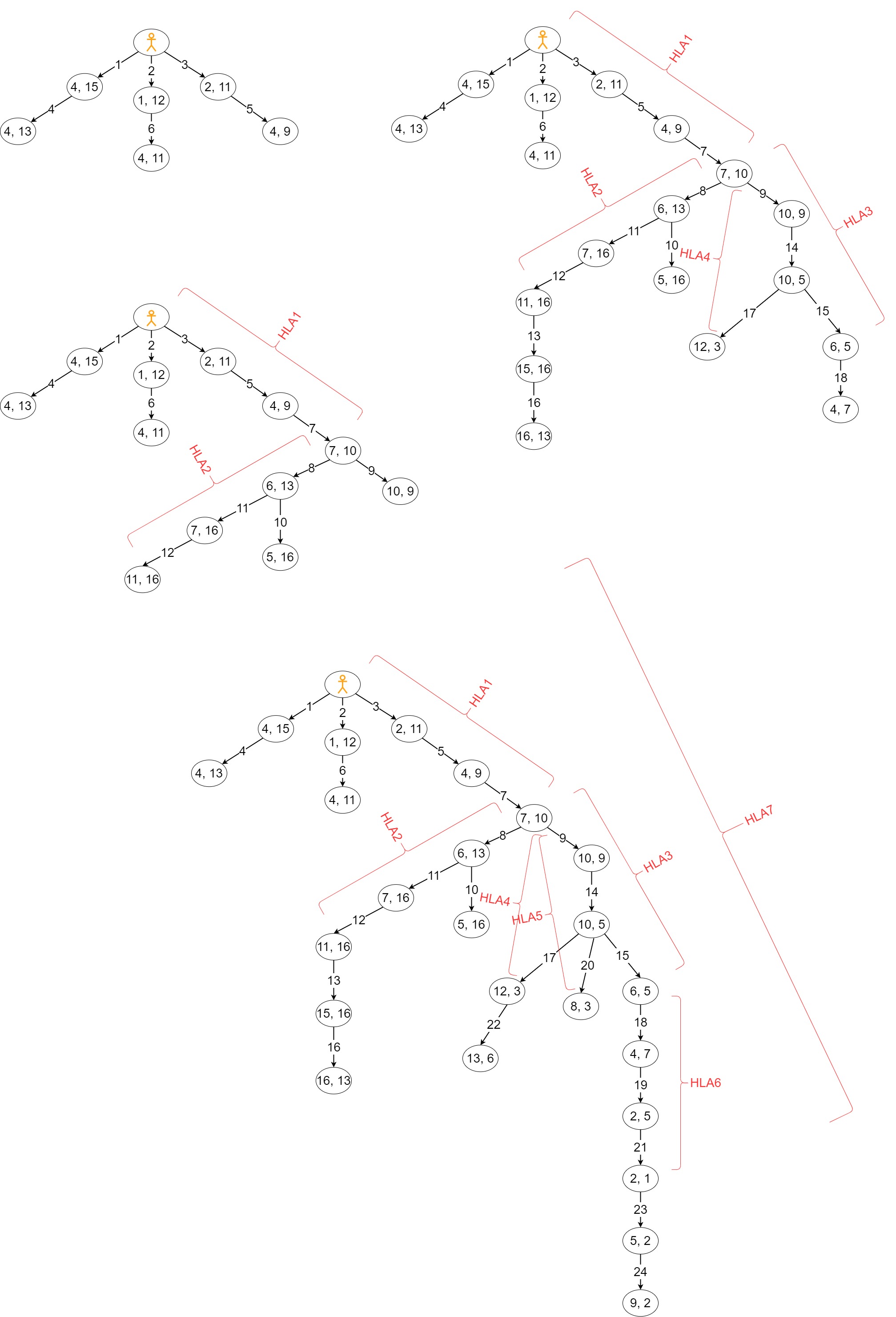

To illustrate some of the ideas mentioned above, look at Figures 2 and 3. Figures 2 shows a maze grid-world where an agent must learn sequences of HLAs to achieve three desired (main) goals. The other figure shows various stages of the plan-tree as it is being grown. The numbers labeling the arrows indicate the order in which the GCPs are generated.

In this work, we take the following approach regarding HLA generation. A newly generated HLA is always a GCP. After a number of linked GCPs (say three) have been generated/learned, they are composed into an HLA at one level higher. And in general, a sequence of HLAs at level are composed into an HLA at level . Of course, some HLAs are at the highest level and do not form part of a higher-level HLA. This approach has the advantage that every behavioral goal at the end of an HLA is reachable if the constituent GCPs exist. The HGCPP algorithm is as follows.

Initialize the root node of the MCTS tree: such that . Initialize current desired goal to focus on.

4.1 Sampling behavioral goals

If the agent decides to explore and thus to generate a new GCP, what should the end-point of the new GCP be? That is, if the agent is at , how does the agent select to learn ? The ‘quality’ of a behavioral goal to be achieved from current exploration point is likely to be based on curiosity (Schmidhuber,, 2006, 1991) and/or novelty-seeking (Lehman and Stanley,, 2011; Conti et al.,, 2017) and/or coverage (Vassilvitskii and Arthur,, 2006; Huang et al.,, 2019) and/or reachability (Castanet et al.,, 2023).

We require a function that takes as argument the exploration point and maps to behavioral goal that is similar enough to that it has good reachability (not too easy or too hard to achieve it, aka a GOID - goal of intermediate difficulty (Castanet et al.,, 2023)). Moreover, of all with approximately equal similarity to , must be the most dissimilar to all children of on average. The latter property promotes novelty and (local) coverage.

We denote the function that selects the ‘appropriate’ behavioral goal when at exploration point as . Some algorithms have been proposed in which variational autoencoders are trained to represent with the desired properties (Khazatsky et al.,, 2021; Fang et al.,, 2022; Li et al.,, 2022): An encoder represents states in a latent space, and a decoder generates a state with similarity proportional the (hyper)parameter. They sample from the latent space and select the most applicable subgoals for the planning phase (Khazatsky et al.,, 2021; Fang et al.,, 2022) or perturb the subgoal to promote novelty (Li et al.,, 2022). Another candidate for representing is the method proposed by Castanet et al., (2023): use a set of particles updated via Stein Variational Gradient Descent “to fit GOIDs, modeled as goals whose success is the most unpredictable.” There are several other works that train a neural network that can then be used to sample a good goal from any exploration point (Shin and Kim,, 2023; Wang et al., 2024b, , e.g.).

In HGCPP, each time the node representing is expanded, a new behavioral goal is generated. Each new to be achieved from must be as novel as possible given the behavioral goal already associated with (i.e. connecting the children of) . We thus propose the following. Sample a small batch of candidate behavioral goals using a pre-trained variational autoencoder and select that is most different to all existing behavioral goals already associated with . The choice of measure of difference/similarity between two goals is left up to the person implementing the algorithm.

4.2 The expansion strategy

For every iteration thru the MCTS tree, for every internal node on the search path, a decision must be made whether to follow one of the generated HLAs or to explore and thus expand the tree with a new HLA.

Let be an estimate for the number candidate behavioral goals around , with being a hyper-parameter proportional to the distance of from . We propose the following exploration strategy, based on the logistic function. Expand node with a probability equal to

| (1) |

where and is the number of GCPs starting in . If we do not expand, then we select an HLA from that maximizes .

4.3 The value of a GCP

Suppose that we are learning policy . Let be a sequence of states and primitive actions such that and . Let be all such trajectories (sequences) experienced by the agent in its lifetime. Then we define the value of with respect to goal as

In words, is the average sum of rewards experienced of actions executes in trajectories from to for pursuing . At the moment, we do not specify whether is given or learned.

4.4 Backpropagation

Only GCPs are directly involved in backpropagation. In other words, we backpropagate values from node to node up the plan-tree as usual in MCTS while treating the GCPs as primitive actions in regular MCTS. The way the hierarchy is constructed guarantees that there is a sequence of linked GCPs between any node reached and the root node.

Every time a GCP and corresponding node are added to the plan-tree, the value of determined just after learning (i.e. ) is propagated back up the tree, for every desired goal. In general, for every GCP (and every non-leaf node ) on the path from the root until , for every goal , we maintain a goal-conditioned value representing the estimated reward-to-go from onwards.

As a procedure, backpropagation is defined by Algorithm 1. Note that and are arrays indexed by goals in .

4.5 The value of a non-GCP HLA

Every non-GCP HLA has a q-value. They are maintained as follows. Let be the sequence of GCPs that constitutes non-GCP HLA . Every non-GCP HLA either ends at a leaf or it does not. That is, either or not.

If is a leaf, then

where is the number of GCPs constituting . Else if is not a leaf, then

where is the node at the end of .

Suppose that has just been generated and its q-value propagated back. Let the path from the root till leaf node be described by the sequence of linked GCPs

| (2) |

Notice that some non-GCP HLAs will be completely or partially constituted by GCPs that are a subsequence of (2). Only these HLAs’ q-values need to be updated.

4.6 Desired goal focusing

An idea is to use a progress-based strategy: Fix the order of the goals in arbitrarily: . Let be true iff: the average reward with respect to experienced over GCP-steps is at least or the number of steps is less than . Parameter is the minimum time the agent should spend learning how to achieve a goal, per attempt. If becomes false while pursuing , then set to zero, and start pursuing if or start pursuing if . Colas et al., (2022) discuss this issue in a section called “How to Prioritize Goal Selection?”.

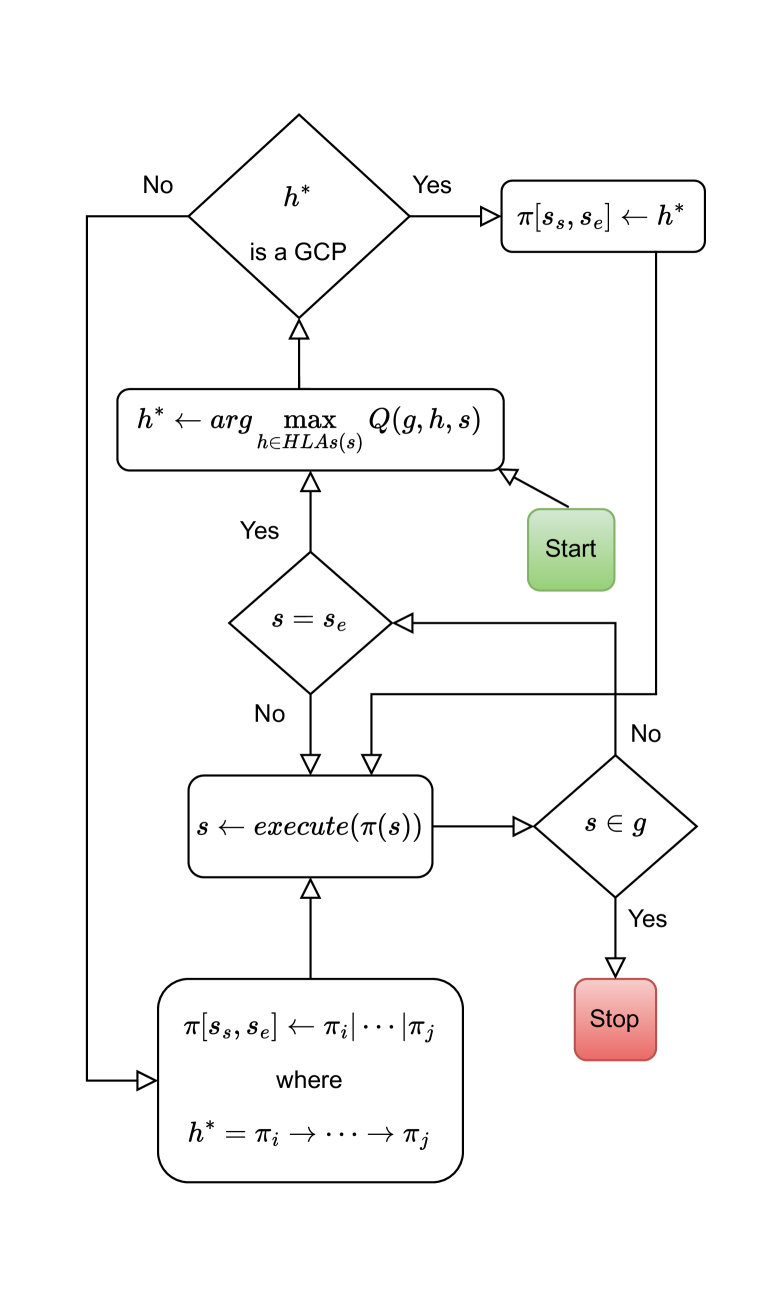

4.7 Executing a task

Once training is finished, the robot can use the generated plan-tree to achieve any particular goal . The execution process is depicted in Figure 4.

Note that means that GCPs and are concatenated to form ; concatenation is defined if and only .

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Learning

Almost any RL algorithm can be used to learn GCPs, once generated. They might need to be slightly modified to fit the GCRL setting. For instance, Kulkarni et al., (2016); Zadem et al., (2023) use DQN (Mnih et al.,, 2015), Ecoffet et al., (2021) uses PPO (Schulman et al.,, 2017), Yang et al., (2022) uses DDPG (Lillicrap et al.,, 2016) and Shin and Kim, (2023); Castanet et al., (2023) use SAC (Haarnoja et al.,, 2018).

5.2 Representation of Functions

The three main functions that have to be represented are the contextual goal-conditioned policies (GCPs), GCP values and goal-conditioned Q functions. We propose to approximate these functions with neural networks.

In the following, we assume that every state is described by a set of features, that is, a feature vector . Recall that a GCP has context state and behavioral goal state . Hence, every GCP can be identified by its context and behavioral goal.

There could be one policy network for all GCPs that takes as input three feature vectors: a pair of vectors to identify the GCP and one vector to identify the state for which an action recommendation is sought. The output is a probability distribution over actions ; the output layer thus has nodes. The action to execute is sampled from this distribution.

There could be one policy-value network for all that takes as input three feature vectors: a pair of vectors to identify the GCP and one vector to identify the state representing the desired goal in . The output is a single node for a real number.

There could be one q-value network for that takes as input four feature vectors: a pair of vectors to identify the HLA , one vector to identify the state and one vector to identify the state representing the desired goal . The output is a single node for a real number.

We could also look at universal value function approximators (UVFAs) for inspiration (Schaul et al.,, 2015).

5.3 Memory

“Experience replay was first introduced by Lin, (1992) and applied in the Deep-Q-Network (DQN) algorithm later on by Mnih et al. (2015).” (Zhang and Sutton,, 2017)

Archiving or memorizing a selection of trajectories experienced in a replay buffer is employed in most of the algorithms cited in this paper. Maintaining such a memory buffer in HGCPP would be useful for periodically updating and the GCP policy network. We leave the details and integration into the high-level HGCPP algorithm for future work.

Also on the topic of memory, we could generalize the application of generated (remembered) HLAs: Instead of associating each HLA with a plan-tree node, we associate them with a state. In this way, HLAs can be reused from different nodes representing equal or similar states.

5.4 Opportunism

Suppose we are attempting to learn . If no trajectory starting in reached after a given learning-budget, then instead of placing in , is placed in , where was reached in at least one experienced trajectory (starting in ) and is the best (in terms of ) of all states reached while attempting to learn . In the formal algorithm (line 3.d.) is either or . This idea of relabeling failed attempts as successful is inspired by the Hindsight Experience Replay algorithm (Andrychowicz et al.,, 2017).

REFERENCES

- Andrychowicz et al., (2017) Andrychowicz, M., Wolski, F., Ray, A., Schneider, J., Fong, R., Welinder, P., McGrew, B., Tobin, J., Abbeel, P., and Zaremba, W. (2017). Hindsight experience replay. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 5048–5058.

- Bortkiewicz et al., (2024) Bortkiewicz, M., Łyskawa, J., Wawrzyński, P., Ostaszewski, M., A., G., Sobieski, B., and Trzciński, T. (2024). Subgoal reachability in goal conditioned hierarchical reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2024), volume 1, pages 221–230.

- Browne et al., (2012) Browne, C., Powley, E., Whitehouse, D., Lucas, S., Cowling, P., Tavener, S., Perez, D., Samothrakis, S., and Colton, S. (2012). A survey of Monte Carlo tree search methods. IEEE Transactions on Computational Intelligence and AI.

- Castanet et al., (2023) Castanet, N., Sigaud, O., and Lamprier, S. (2023). Stein variational goal generation for adaptive exploration in multi-goal reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, volume 202. PMLR.

- Colas et al., (2022) Colas, C., Karch, T., Sigaud, O., and Oudeyer, P.-Y. (2022). Autotelic agents with intrinsically motivated goal-conditioned reinforcement learning: A short survey. Artificial Intelligence Research, 74:1159–1199.

- Conti et al., (2017) Conti, E., Madhavan, V., Such, F. P., Lehman, J., Stanley, K. O., and Clune, J. (2017). Improving exploration in evolution strategies for deep reinforcement learning via a population of novelty-seeking agents. In 32nd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2018).

- Ecoffet et al., (2021) Ecoffet, A., Huizinga, J., Lehman, J., Stanley, K., and Clune, J. (2021). First return, then explore”: First return, then explore. Nature, (590):580–586.

- Fang et al., (2022) Fang, K., Yin, P., Nair, A., and Levine, S. (2022). Planning to practice: Efficient online fine-tuning by composing goals in latent space. In IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS).

- Fang et al., (2019) Fang, M., Zhou, T., Du, Y., Han, L., and Zhang, Z. (2019). Curriculum-guided hindsight experience replay. In 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019).

- Florensa et al., (2018) Florensa, C., Held, D., Geng, X., and Abbeel, P. (2018). Automatic goal generation for reinforcement learning agents. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, volume 80. PMLR.

- Haarnoja et al., (2018) Haarnoja, T., Zhou, A., Abbeel, P., and Levine, S. (2018). Soft actor-critic: Offpolicy maximum entropy deep reinforcement learning with a stochastic actor. In International conference on machine learning, volume 80, pages 1861–1870. PMLR.

- Hengst, (2012) Hengst, B. (2012). Hierarchical approaches. In Reinforcement Learning: State-of-the-Art, volume 12 of Adaptation, Learning, and Optimization, chapter 9. Springer.

- Hu et al., (2023) Hu, W., Wang, H., He, M., and Wang, N. (2023). Uncertainty-aware hierarchical reinforcement learning for long-horizon tasks. Applied Intelligence, 53:28555–28569.

- Huang et al., (2019) Huang, Z., Liu, F., and Su, H. (2019). Mapping state space using landmarks for universal goal reaching. In 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019), volume 32, pages 1942–1952.

- Kaelbling, (1993) Kaelbling, L. P. (1993). Learning to achieve goals. In Proceeding of IJCAI-93, pages 1094–1099. Citeseer.

- Khazatsky et al., (2021) Khazatsky, A., Nair, A., Jing, D., and Levine, S. (2021). What can i do here? learning new skills by imagining visual affordances. In International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), pages 14291–14297. IEEE.

- Kim et al., (2021) Kim, J., Seo, Y., and Shin, J. (2021). Landmark-guided subgoal generation in hierarchical reinforcement learning. In 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2021).

- Kocsis and Szepesvari, (2006) Kocsis, L. and Szepesvari, C. (2006). Bandit based monte-carlo planning. In European Conference on Machine Learning.

- Kulkarni et al., (2016) Kulkarni, T. D., Narasimhan, K. R., Saeedi, A., and Tenenbaum, J. B. (2016). Hierarchical deep reinforcement learning: Integrating temporal abstraction and intrinsic motivation. In 30th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2016).

- Lehman and Stanley, (2011) Lehman, J. and Stanley, K. O. (2011). Novelty search and the problem with objectives. In Genetic Programming Theory and Practice IX (GPTP 2011).

- Li et al., (2022) Li, J., Tang, C., Tomizuka, M., and Zhan, W. (2022). Hierarchical planning through goal-conditioned offline reinforcement learning. In Robotics and Automation Letters, volume 7. IEEE.

- Li et al., (2023) Li, W., Wang, X., Jin, B., and Zha, H. (2023). Hierarchical diffusion for offline decision making. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, volume 202, pages 20035–20064. PMLR.

- Lillicrap et al., (2016) Lillicrap, T. P., Hunt, J. J., Pritzel, A., Heess, N., Erez, T., Tassa, Y., Silver, D., and Wierstra, D. (2016). Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

- Lin, (1992) Lin, L.-H. (1992). Self-improving reactive agents based on reinforcement learning, planning and teaching. Machine learning, 8(3/4):69–97.

- Liu et al., (2015) Liu, C., Xu, X., and Hu, D. (2015). Multiobjective reinforcement learning: A comprehensive overview. In IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems, volume 45, pages 385–398. IEEE.

- Liu et al., (2022) Liu, M., Zhu, M., and Zhangy, W. (2022). Goal-conditioned reinforcement learning: Problems and solutions. In Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-22).

- Lu et al., (2020) Lu, L., Zhang, W., Gu, X., Ji, X., and Chen, J. (2020). Hmcts-op: Hierarchical mcts based online planning in the asymmetric adversarial environment. Symmetry, 12(5):719.

- Luo et al., (2024) Luo, Y., Ji, T., Sun, F., Liu, H., Zhang, J., Jing, M., and Huang, W. (2024). Goal-conditioned hierarchical reinforcement learning with high-level model approximation. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON NEURAL NETWORKS AND LEARNING SYSTEMS.

- Mezghani et al., (2022) Mezghani, L., Sukhbaatar, S., Bojanowski, P., Lazaric, A., and Alahari, K. (2022). Learning goal-conditioned policies offline with self-supervised reward shaping. In 6th Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL 2022).

- Mnih et al., (2015) Mnih, V., Kavukcuoglu, K., Silver, D., Rusu, A. A., Veness, J., Bellemare, M. G., Graves, A., and Riedmiller, M. (2015). Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature, 518(7540):529–533.

- Nasiriany et al., (2019) Nasiriany, S., Pong, V. H., Lin, S., and Levine, S. (2019). Planning with goal-conditioned policies. In 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019).

- Park et al., (2023) Park, S., Ghosh, D., Eysenbach, B., and Levine, S. (2023). Hiql: Offline goal-conditioned rl with latent states as actions. In 37th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2023).

- Pertsch et al., (2020) Pertsch, K., Rybkin, O., Ebert, F., Finn, C., Jayaraman, D., and Levine, S. (2020). Long-horizon visual planning with goal-conditioned hierarchical predictors. In 34th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2020).

- Pinto and Coutinho, (2019) Pinto, I. P. and Coutinho, L. R. (2019). Hierarchical reinforcement learning with monte carlo tree search in computer fighting game. IEEE Transactions on Games, 11(3):290–295.

- Plaat, (2023) Plaat, A. (2023). Deep Reinforcement Learning. Springer Nature.

- Schaul et al., (2015) Schaul, T., Horgan, D., Gregor, K., and Silver, D. (2015). Universal value function approximators. In Proceedings of ICML-15, volume 37, pages 1312–1320.

- Schmidhuber, (1991) Schmidhuber, J. (1991). Curious model-building control systems. In Proceedings of Neural Networks, 1991 IEEE International Joint Conference, pages 1458–1463.

- Schmidhuber, (2006) Schmidhuber, J. (2006). Developmental robotics, optimal artificial curiosity, creativity, music, and the fine arts. Connect. Sci., 18:173–187.

- Schulman et al., (2017) Schulman, J., Wolski, F., Dhariwal, P., Radford, A., and Klimov, O. (2017). Proximal policy optimization algorithms. CoRR, abs/1707.06347.

- Shin and Kim, (2023) Shin, W. and Kim, Y. (2023). Guide to control: Offline hierarchical reinforcement learning using subgoal generation for long-horizon and sparse-reward tasks. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Second International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-23), pages 4217–4225.

- Sutton et al., (2011) Sutton, R. S., Modayil, J., Delp, M., Degris, T., Pilarski, P. M., White, A., and Precup, D. (2011). Horde: A scalable real-time architecture for learning knowledge from unsupervised sensorimotor interaction. In Proceeding of 10th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, volume 2, pages 761–768.

- Sutton et al., (1999) Sutton, R. S., Precup, D., and Singh, S. P. (1999). Between mdps and semi-mdps: A framework for temporal anstraction in reinforcement learning. Artificial Intelligence, 112(1-2):181–211.

- Vassilvitskii and Arthur, (2006) Vassilvitskii, S. and Arthur, D. (2006). k-means++: The advantages of careful seeding. In Proceedings of the eighteenth annual ACM-SIAM symposium on discrete algorithms, page 1027–1035.

- (44) Wang, M., Jin, Y., and Montana, G. (2024a). Goal‑conditioned offline reinforcement learning through state space partitioning. Machine Learning, 113:2435–2465.

- (45) Wang, V. H., Wang, T., Yang, W., K am ar ainen, J.-K., and Pajarinen, J. (2024b). Probabilistic subgoal representations for hierarchical reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning, volume 235. PMLR.

- W ohlke et al., (2021) W ohlke, J., Schmitt, F., and van Hoof, H. (2021). Hierarchies of planning and reinforcement learning for robot navigation. In International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA 2021), pages 10682–10688. IEEE.

- Yang et al., (2022) Yang, X., Ji, Z., Wu, J., Lai, Y.-K., Wei, C., Liu, G., and Setchi, R. (2022). Hierarchical reinforcement learning with universal policies for multi-step robotic manipulation. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 33(9):4727–4741.

- Zadem et al., (2023) Zadem, M., Mover, S., and Nguyen, S. M. (2023). Goal space abstraction in hierarchical reinforcement learning via set-based reachability analysis. In 22nd IEEE International Conference on Development and Learning (ICDL 2023), pages 423–428.

- Zhang and Sutton, (2017) Zhang, S. and Sutton, R. S. (2017). A deeper look at experience replay. In 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017).