Saturation for the -Uniform Loose -Cycle

Abstract

Let and be -uniform hypergraphs. We say is -saturated if does not contain a subgraph isomorphic to , but does for any hyperedge . The saturation number of , denoted , is the minimum number of edges in a -saturated -uniform hypergraph on vertices. Let denote the -uniform loose cycle on edges. In this work, we prove that

This is the first non-trivial result on the saturation number for a fixed short hypergraph cycle.

Dedicated to the memory of Landon Rabern

1 Introduction

Let and be -uniform hypergraphs. We say is -free if does not contain as a sub-hypergraph. One of the central problems in extremal combinatorics is to determine the Turán number of , denoted , and defined

We say that is -saturated if is -free, but contains a copy of for every hyperedge . Since each -free graph with is -saturated, Turán numbers can be defined in terms of maximizing the number of edges over -saturated graphs rather than -free graphs. A consequence of this phrasing of the definition is that it leads to a natural minimization problem related to Turán numbers. Originally introduced by Erdős, Hajnal and Moon [12] using different terminology, the saturation number, is defined by

Kászonyi and Tuza [19] proved that , and then Pikhurko [24] proved that for general , .

In the seminal paper [12], Erdős, Hajnal and Moon determined the saturation numbers for graph cliques exactly. The first result for saturation of -uniform hypergraphs is due to Bollobás [3], and in this work, the method known as the set-pair method [27] was first developed. In addition to complete graphs, different trees have received careful study (e.g. [13, 19]). In terms of hypergraphs, most of the specific saturation numbers determined outside of complete graphs involve forbidden families of hypergraphs, such as triangular families [25], intersecting hypergraphs [8], and very recently Berge hypergraphs (e.g. [1, 2, 10, 11, 17]). For a detailed dynamic survey on all aspects of saturation in graphs and hypergraphs, see [14].

1.1 Saturation for Cycles

One of the families of graphs that have received the most attention in saturation literature is cycles. While cycles have received considerable attention, very few exact results have been obtained. For specific short graph cycles, the following bounds are known (We assume is large enough for results below):

Aside from these small cases, the best-known bounds on for fixed are obtained by Füredi and Kim [16]:

Of note is the fact that even for graphs, the asymptotics for saturation numbers of cycles is not known already for cycles of length or more. Also of note, for the -cycle, through a technical feat, it was shown that there are exactly distinct minimal constructions, some of which are specific graphs that only work for one value of , others which constitute infinite families [6]. This highlights a difficulty in studying the saturation function in general and for cycles - one usually does not expect to prove a nice stability result when there are multiple different extremal examples.

Saturation numbers for the family of all cycles of length above a certain value have also been studied, with exact results determined for [15, 22]. In addition to these results involving cycles of short length, many results on the saturation numbers of Hamiltonian cycles have been studied, with numerous results leading up to proving that (upper bound given first in [4], while the lower bound can be found in [21]).

When passing from graphs to hypergraphs, there are many ways to generalize the notion of a cycle. One of the more general notions of a cycle in a hypergraph is an -overlapping cycle. Namely, the -uniform -overlapping cycle on edges is the unique -uniform hypergraph on vertices and edges such that there exists an ordering of the vertex set, say such that is an edge for each (indices taken modulo ). When , we will simply call this hypergraph the -uniform loose cycle on edges, and denote it by .

Up until this work, the entire literature involving saturation for -overlapping cycles has been for Hamiltonian cycles (for a -uniform -overlapping Hamiltonian cycle to exist in an -vertex graph, we must have ). In this setting, due to the difficulty in such problems, the work has been mostly focused on determining the order of magnitude for which these saturation numbers grow (see e.g. [9, 20, 26] for some of the results in this direction).

1.2 Main Result

In this work, we study the saturation function for a short loose cycle, namely . Our main result is as follows.

Theorem 1.1.

We have that

To the authors best knowledge, this is the first non-trivial result on saturation numbers for a specific hypergraph cycle of fixed length (the first author and others did provide some bounds on saturation for short Berge hypergraphs cycles in [11], but in general results involving families of hypergraphs tend to be easier than results involving a single hypergraph).

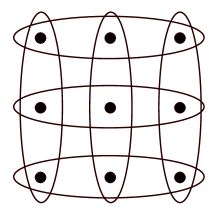

It is worth noting that at least for small values of , the in the lower bound is necessary, as for example one might note that (See Figure 1 for the optimal construction). The authors think that for large , the upper bound is more likely to be asymptotically correct than the lower bound.

The proof of our main result is broken up as follows. In Section 2, we provide a relatively straightforward deterministic construction on edges and show that this construction is saturated. In the remaining sections of the paper we show the more involved lower bound. The proof uses the technique of asymptotic discharging. For a primer on discharging, see [7]. Normally in a discharging proof, it would be shown that certain small structures are reducible, i.e. they cannot exist in a minimum counterexample to a proposition. Here we allow many configurations to exist, but only in numbers small enough that their existence does not affect the leading term of the final bound. In Section 3, we provide a high-level proof sketch that goes through the main ideas of the proof without the technical details. Then in Sections 4, 5 and 6, we provide the main structural results necessary for the discharging proof, and finally in Section 7, we give our discharging scheme and provide the proof of the lower bound using this discharging scheme.

1.3 Notation and Definitions

Given a cycle , we will call the vertices of degree the core vertices of the cycle. We may refer to as a triangle.

Vertices of degree in a graph will be called -vertices, and -vertices adjacent to a vertex will be called -neighbors of . For , denotes the set of vertices such that some edge of contains and some vertex in , and . Given a pair of vertices and , we write to denote the co-degree of the pair, i.e. the number of edges that contain both and . We may say that is a double neighbor or triple neighbor of if or respectively.

Given a graph and sets , we will say an edge is an edge if (after possibly renaming) , and . If one of the sets , or is of the form for some , we will often just write the number in place of the set. For example, we may say an edge is an edge if contains one vertex in the set , one vertex of degree , and one vertex of degree . Finally, if one of the sets is of the form for some , we will simply write in place of the set.

For , a -link is a -edge loose path from to . The common vertex of the two edges of is the center of . If there exists a -link in , we will say is a good pair, and if not, we will say is a bad pair.

2 Upper Bound - A Construction

Let be an integer. We now present a construction, , that has vertices and edges.

Construction 2.1.

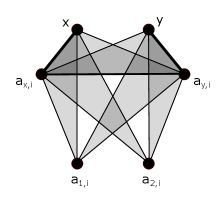

Let and be integers such that and . For each with , let denote the -uniform hypergraph on vertices and edges with and

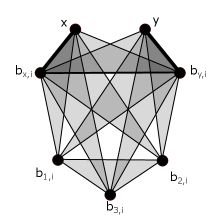

Furthermore, for each with , let denote the hypergraph on vertices and edges such that and

Now, let be union of the ’s and ’s, and note that

while

We call each of the subgraphs or a brick of . See Figure 2 for drawings of the two types of bricks in .

Theorem 2.2.

The hypergraph from Construction 2.1 is -saturated for all . Consequentially,

Proof.

First we will show that is -free. Assume to the contrary that contains a copy, , of , and note that all the core vertices of must be contained in the same brick of since they are adjacent. Furthermore, and cannot both be core vertices, so this implies must be completely contained inside one brick of . However it can be directly verified that neither type of brick contains a copy of . Thus, is -free.

Now we will show that is -saturated. Let be any triple of vertices such that . First note that every brick of contains an -link, so if both and are in , then this creates a , so we may assume at least one of or is not in . Furthermore, under this assumption, it can be directly verified that if all three vertices in are contained in a single brick of , this creates a within that brick, so we may assume otherwise.

Case 1: contains exactly one of or . Assume without loss of generality that . Let be the other two vertices of , and note that and must be in different bricks of . However, every vertex in every brick is in an edge that contains but not . Thus , along with the edge containing and , but not , and the edge containing and , but not , form a .

Case 2: and intersects only two bricks of . Let where and are in the same brick. It can be readily verified that regardless of which vertices and are in this brick, there is an edge in that contains exactly one of or and one of or , say that it contains and , but not . This edge, along with any edge containing and , and form a in .

Case 3: and intersects three distinct bricks. Let . Then along with any edge containing and , and any edge containing and , form a in .

Thus, in all cases, we find a in , so is saturated. ∎

3 Lower Bound: Proof Sketch

We will assume for the rest of the paper that is large, and that is a -saturated -uniform hypergraph on vertices with edges. By Theorem 2.2, we can crudely assume

At the simplest level, the goal of our proof will be to show that the average degree of is at least . To do this, we will use a discharging scheme: every vertex will start with charge equal to its degree, and we will then move charge around according to certain rules until the following two things are satisfied:

-

•

Every vertex has non-negative charge, and

-

•

vertices have charge at least .

In particular, charge will always be moved around via edges, i.e. any time our discharging rules move charge from one vertex to another, they will be adjacent.

Let be a function that tends to infinity with (but slowly). Let

and

We will call the vertices in low vertices of , and the vertices in non-low vertices. Since , we have

Since there are few vertices in , they can give all their charge to vertices in . We also will need to keep track of vertices whose degree is almost linear in . In particular, let

We will call vertices in high vertices. Note that for a vertex being non-low is a much weaker condition than being high.

Furthermore, for we will denote by the set of vertices of degree at most . So, . We will say a vertex is -flat if the total number of vertices in in all edges containing (counted with multiplicities) is exactly , and is -flat if is -flat for some .

One of the first results we will prove (Lemma 4.1) implies that there is a set of two vertices, and such that almost all vertices in that are not adjacent to at least two vertices in are in . Among other things, this implies that almost all vertices in are adjacent to at least one vertex in , which will be very helpful.

3.1 Simple discharging rules that do not work

To motivate the rest of the proof, it is useful to mention a simple discharging scheme that does not work, but is the basis for the more complicated discharging rules we use.

The following simple discharging rules do not create or destroy charge, they simply move it (we add an asterisk to the label for these rules because they are not the final discharging rules we use, and are instead simply a heuristic to motivate our final rules):

-

(D1*)

Every edge with removes charge from and gives charge to each of and .

-

(D2*)

Every edge with removes charge from each of and , and gives charge to .

Under this discharging scheme, every vertex in ends up with non-negative charge while vertices in only receive extra charge beyond the initial charge they had from their degree, making them more likely to end up above charge . However, it is possible that many vertices in do not get up to charge .

Now by this simple discharging scheme, every -flat vertex in gets extra charge at least from vertices in , but without more information, we cannot guarantee a vertex gets any more than this. Aside from -flat vertices (which we already know there are few of by Lemma 4.1), this scheme leaves the following types of vertices in below charge :

-

•

-flat -vertices,

-

•

-flat -vertices,

-

•

-flat -vertices, and

-

•

-vertices and -vertices.

We will show that there are very few -vertices and -vertices. However, it is possible that contains vertices of any of the other three types listed above. To deal with this, we introduce more complicated discharging rules, both refining the rule (D1*) (i.e. still moving charge from vertices in to vertices in , but possibly not splitting charge evenly among the low vertices in an edge), as well as introducing some rules which will move charge from vertices in that have excess charge to other vertices in that are not satisfied by their non-low neighbors.

3.2 Overview of how to deal with -flat -vertices

We wish to enact a discharging rule such as

-

(D1.1*)

Every edge with , and a -flat -vertex removes charge from and gives charge to .

If this rule were well-defined, then every -flat -vertex would receive an extra charge , bringing them up to charge . Thus, the goal of Section 5 will be to show that a rule very similar to this is well-defined, and that the rule does not cause any other vertices to end up with too little charge. In particular, we will establish claims that essentially imply the following:

-

•

There are very few edges,

-

•

There are very few edges containing either two -flat -vertices or a -flat -vertex and a -flat -vertex, and

-

•

There are very few -flat -vertices that are in two or more edges with -flat -vertices.

Together these statements will imply that for almost all -flat -vertices, a rule like (D1.1*) will leave them with charge , while not having many -flat -vertices end up with charge less than .

3.3 Overview of how to deal with -vertices

The simple discharging scheme presented above leaves both -flat and -flat -vertices with charge less than . We again wish to refine the rule (D1*) to prioritize giving -vertices more charge. For example, we wish to enact a discharging rule similar to

-

(D1.2*)

Every edge with , , and removes charge from and gives charge to .

As with rule (D1.1*), it is not obvious that this rule is well-defined, and also it is possible this rule conflicts with (D1.1*). However we will show that there are very few or edges, which implies that for almost all -vertices, (D1.2*) is well-defined and does not conflict with (D1.1*).

(D1.2*) is enough for -flat -vertices to get charge , but -flat -vertices would still be left with only charge . To deal with this, we need to move charge from vertices in to -flat -vertices. In Section 6, we will define the concept of a low vertex being “helpful”, which essentially will imply that these low vertices have enough charge to give to each of their -flat -neighbors (with multiplicity), while still being satisfied. This will allow us to enact a discharging rule like

-

(D3*)

Every edge with being a “helpful” vertex and being a -flat -vertex will remove charge from and give charge to .

If we could show that almost every edge containing a -flat -vertex also contained a helpful vertex, (D3*) would be enough to satisfy almost all -flat -vertices, since they would get an extra charge from each of their two edges, bringing them up to charge . Unfortunately, it is unclear if this is true.

To deal with this, we use a second round of moving charge from vertices in to -flat -vertices, this time asking for a little less from the “helping” vertex. In particular, we define “half-helpful” vertices, which essentially are vertices in that may not have had enough charge to be “helpful”, but can give to all the -flat -neighbors that weren’t already satisfied by the charge moved via (D3*). This leads us to a rule like

-

(D4*)

Every edge with being “half-helpful”, and being a -flat -vertex that still does not have charge after the implementation of all previous rules, takes charge from and gives charge to .

In order to make sure that (D3*) and (D4*) are well-defined and satisfy almost all -vertices, we will need to prove claims that essentially imply the following:

-

•

There are almost no edges, and

-

•

Every edge that contains a -flat -vertex also contains a “helpful” or ”half-helpful” vertex.

All of this is done in Section 6.

3.4 One More Discharging Rule

In order to guarantee that we have enough “helpful” and “half-helpful” vertices in , we will further refine (D1*) to move charge away from vertices that we expect to have a lot of extra charge (say vertices of degree more than ) to other vertices. We will classify edges as “rich” and name one of the low vertices in every “rich” edge as the “recipient” if we expect the second vertex of this “rich” edge to be “helpful” even without charge from this edge (for example if a vertex is degree or more). Thus, we will enact a rule like:

-

(D1.3*)

Every “rich” edge with and recipient removes charge from and gives charge to .

These heuristic discharging rules capture most of the main ideas of the proof. In Section 7, we go through the actual discharging scheme we use.

The final main idea in our proof that has not been mentioned here is the use of “garbage sets”, i.e. small sets of vertices with numerous “bad” properties, which we will show we can largely ignore. In particular, throughout this heuristic section we have used the phrase “almost all” quite loosely. In order to rigorously show that vertices end up with charge at least , we will define a sequence of “garbage sets”, . We will show that the union of these sets is and that all vertex in outside of these sets indeed end up with charge at least after the discharging rules take place.

As we define the “garbage sets” , we often want to exclude not just the vertices in , but low vertices that are neighbors of as well. Some of these “garbage sets” could be around size , so we may not be able to include all low neighbors if a “garbage set” contains any vertices of degree close to . We will however usually include all low neighbors of the vertices of degree at most inside a “garbage set”. To that end, given a garbage set , we will usually define a set that contains all the previously defined garbage sets, and then a set which contains , along with any vertices in that have a neighbor of degree at most in .

4 Lower Bound: Preliminary Lemmas

Lemma 4.1.

Let denote the set of vertices which have at least two neighbors in and let . There exist two vertices, with such that

Proof.

We will prove a slightly stronger statement, which implies our result. Namely, we will prove the following: If , then there either exists

-

•

a pair of vertices such that , or

-

•

a single vertex such that .

Let . We claim that there are no partitions and such that , and such that for .

Indeed, if we consider the triples that contain one vertex in each set , of these must be non-edges, and thus must contain a good pair. Let be one such good pair. Then can cover at most of the non-edges, so there must be at least

| (1) |

good pairs with endpoints in different ’s. Note that no vertices in can serve as the center of a -link connecting any of these good pairs since the pairs contains vertices in two different ’s, and since each other vertex can be the center of a link including at most other vertices, we have that there are at most

| (2) |

such good pairs, where the last inequality follows from Theorem 2.2. However, this and the value of contradict (1), so no such partition could exist.

Now, if there exist two vertices with , then

since otherwise would give us a partition that we know does not exist, so in this case we are done.

If there is exactly one vertex with , then , since otherwise we could partition into two sets such that by starting with all the vertex of in , and then moving them one at a time into until the first time the inequality is satisfied. This further implies that , so would be a partition that we know does not exist.

Finally, if no vertices in are adjacent to at least vertices in , then we can find a partition with for and consequently , again by starting with all the vertex in in , moving them one at a time into until the first inequality is satisfied, then one at a time into until the second is satisfied, giving us a partition we know does not exist. ∎

Let be the set of vertices of degree at most in the set as defined in Lemma 4.1. Let .

Remark 4.2.

Since , Lemma 4.1 yields

We now focus on vertices that are in pairs with high codegree relative to their degree.

Claim 4.3.

Let . If , then . Furthermore, if , then is the only degree double neighbor of .

Proof.

First, assume that while . If , then for any the non-edge intersects every edge containing or in two vertices, so does not contain a , a contradiction. Thus, we can assume .

Suppose , and let be the single edge that contains but not . If , then consider the non-edge . This non-edge intersects every edge containing or in two vertices, so again is -free, again a contradiction. Thus, we may assume , and similarly .

Now consider the non-edge and let be the in . A -link that avoids would also avoid since is in every edge that is in except , so cannot be the set of core vertices of , thus is a core vertex. Without loss of generality, assume is the second core vertex. Then any -link must use some edge where , and a second edge for some . But then , and form a in , a contradiction. Thus, .

Now assume that and that there exists a vertex with as well. If , then adding it cannot create a since this non-edge intersects all edges containing and in two vertices. Thus, we may assume is an edge of .

Let and be the other edges containing and , respectively. If , then the non-edge again intersects all edges containing either or in two vertices, another contradiction. Thus we have .

Now consider the non-edge . As this non-edge intersects every edge containing in two vertices, there is a -link that avoids . To avoid a in with the edge , must be contained in this link, but every edge containing intersects in two vertices, which is a contradiction. This proves the claim. ∎

Claim 4.4.

Let . No edge not containing can have two -vertices in .

Proof.

Suppose to the contrary that , where and . By definition, for there is an edge . By Claim 4.3, since -vertices cannot be double neighbors with each other.

Let . Since and , . Thus has a copy of , that contains the edge . The edge intersects all edges containing and in two vertices, so neither of these vertices can be core vertices in , a contradiction. ∎

Claim 4.5.

If is an edge in , and is a good pair, then is a double neighbor of or .

Proof.

If is a good pair, then there is an -link. If this link does not contain , then together with they form a in , a contradiction. Thus, one of the edges of the loose path contains , which implies is a double neighbor of or . ∎

Let be the set of vertices such that there exists some where is a bad pair and . Let , and let .

Lemma 4.6.

.

Proof.

For a vertex , let be the set of vertices such that is a bad pair and . For , the condition that implies that is the only vertex in adjacent to , and further the condition that implies that . Thus .

Fix some and let . Let . Note that since . Let . Since , . Then if , there exists some . Adding the edge gives a contradiction, since cannot be a core vertex because and are bad pairs, and and are too far apart in to be core vertices together. Thus the number of choices for adjacent to is at most .

Since , this yields . ∎

Let be the set of -flat vertices such that there exists an edge with and . Let , and let .

Lemma 4.7.

.

Proof.

The only vertices in that are adjacent to -flat vertices outside of are and . For , let be the family of edges such that , is a -flat vertex of degree at most , and . We will show that , which will imply that .

Suppose to the contrary that and let . Let be the set of the vertices in , and . Since , and . Since , each vertex adjacent to can be in at most one edge in in the role of . Hence contains less than vertices in the role of in . Thus there is an edge such that is -flat and is not in .

Consider the non-edge . By Claim 4.5, since , is a bad pair, so there is a -link avoiding or a -link avoiding . This link cannot contain since the only edge containing and one of or contains both. So since is -flat, this link must use a low edge containing , and some other edge connecting this to one of or . But then , a contradiction. Thus, . ∎

Let be the set of vertices such that there exists an with . Let , and let .

Lemma 4.8.

.

Proof.

Fix a vertex . Note that if and are both vertices such that and , then since if not, adding cannot create a in as it intersects every edge containing and in at least two vertices. We claim that has at most neighbors with such that . Indeed, if had such neighbors, say , then must be in edges, namely , contradicting the fact that .

Since every vertex has at most such neighbors, the total number of vertices such that and for some is at most

∎

It is perhaps worth noting that all -vertices and -vertices end up in since they are either contained in or in .

Lemma 4.9.

For each and each neighbor of with and , one of the following holds:

-

(a)

there is an edge such that or is not -flat and , or

-

(b)

there are two edges and such that neither of and is a -flat -vertex.

Proof.

Suppose that for some with neither of (a) and (b) holds. This means that there are vertices such that for , and at least one of them, say , is a -flat -vertex. Since , , and hence is a good pair. Let edges and form a -link with . In order to avoid a triangle with edges and in , or contains .

Case 1: . Then , so that has the form and has the form for some . If , then contains triangle with edges and , a contradiction. Otherwise, the co-degree of is at least . Since , , and hence cannot be a double neighbor of of degree . Thus Part (a) of the claim of the lemma holds.

Case 2: . Then , so that has the form and has the form for some . By symmetry, we may assume . If or is a not -flat -vertex, then Part (a) of the lemma holds. If , then the non-edge intersects each of the edges containing or in two vertices. Thus neither of or could be a core vertex in a triangle in . This yields . So, if (a) does not hold, then

| is a -flat -vertex. | (3) |

Let . Since we know both edges containing , . So contains a triangle, say with edges and . Since each of the edges containing has two common vertices with , and form a -link. We may assume that .

Since has no triangle with edges and , . Since by (3) the co-degree of is , has the form and has the form for some . If is not a -flat -vertex, then Part (b) of the the lemma holds. So suppose is a -flat -vertex.Then we know all edges containing at least one of and . In particular, edge is not in , and hence must contain a triangle. However, the edges containing at least one of and and sharing less than two vertices with are only and . Any two of these edges share and , a contradiction.

Case 3: . We may assume that and . In particular, . Consider and as in Case 2. Again, there are edges and forming a -link. Since , ; thus is -flat. Then , so we may assume and for some . So, we have Case 2 with in the role of . ∎

4.1 Edges of type

We have two goals in this section. First, we want to prove a structural result which tells us essentially that in almost all edges, either such an edge contains a good pair involving the vertex in , or the two low vertices in the edge are connected via a tight path of length . Second, we will use this structural result to show that there are only few or edges in .

Let be the set of vertices such that there exists an edge with the following properties

-

•

and ,

-

•

and are bad pairs, and

-

•

there are no edges and for some .

Let , and let .

Lemma 4.10.

.

Proof.

Fix . We claim that is in at most edges that satisfy the conditions in the definition of . To see this, assume to the contrary that is in at least such edges. Note that each such edge containing can intersect at most other edges in two vertices, possibly other such edges containing and one containing . Thus, we can find a collection of such edges that only intersect in the vertex .

Call these edges , and let , where . Furthermore, let be the second edge containing . Consider the non-edge for some , . Since and are bad pairs, there is a -link that avoids . Thus, this link consists of the edges and .

Now, fix , and let and denote the sets of vertices with such that and respectively. One of or must have size at least , so assume without loss of generality , and by reordering if necessary, we can assume that for .

Now consider the non-edge for each . By assumption, and are bad pairs, so there is a -link that avoids . This link must use the edge . Note that the second edge of this link cannot be of the form since if , then recalling that , this gives us that and are edges, contradicting the initial assumption of the lemma, and if , then the edges , and form a in . Thus, there must be an edge where . So, is adjacent to for all .

Now, since for all with , we have that for all , . Thus, , which contradicts the fact that (and consequently, .

This establishes that indeed, every vertex is in at most such edges. Thus,

∎

We now use the above lemma to prove that there are very few and edges.

Lemma 4.11.

Let and let be a or edge, where . Then and are bad pairs.

Proof.

By Claim 4.3, and cannot be double neighbors since one of them is degree , and the other is degree at most .

Assume that is a good pair. To avoid having a in , any -link must contain . Since is not a double neighbor of , this implies that we have edges and for some vertices . Since is a double neighbor of and is not in , we have , and consequently .

Consider the non-edge . If , then this non-edge intersects every edge containing and in two vertices, so cannot contain a . Thus, . Furthermore, since intersects every edge containing in two vertices, there exists a -link that avoids . To avoid a in , must be in this link. Since is not in , , so this -link must contain edges of the form and . But this creates a in with , a contradiction. ∎

Lemma 4.12.

Let and let be a or a edge of , where . Let and for some . Then at most one of or is in .

Proof.

Suppose contains all the edges , and for some . If , then the edge is not an edge of , but it intersects every edge containing either or in two vertices. So adding this edge to does not create a . Thus, we may assume that is a edge, say with and . If , then the non-edge intersects every edge containing and in two vertices, so cannot contain a , a contradiction. Thus . Similarly, .

Suppose now that , say , and note that . Consider the non-edge , and let be a in . If and are core vertices in , then any -link must contain . But every edge that contains and one of or intersects in two vertices, so and cannot both be core vertices. Thus is a core vertex of . So, is one of the edges of . By Lemma 4.11, is a bad pair, so must be the second core vertex of . Thus, there exists some edge containing and exactly one of or , say without loss of generality . Note that , and thus , and form a in , a contradiction. Thus, .

Let be such that , and note that . Consider the non-edge . By Claim 4.5, is a bad pair since , and thus there is a -link avoiding or a -link avoiding . Assume the former. If this -link uses the edge , then it must also use an edge for some since the only edge containing is . But then , and form a in , a contradiction. If instead, the link uses the edge , then it must also use an edge containing exactly one of or and , but not , say for some . Again we reach a contradiction since , and form a in . Thus, in all cases we arrive at a contradiction. ∎

Lemma 4.12 together with the definition of yield the following.

Corollary 4.13.

For every or edge where , vertices and are in .

5 Lower Bound: -flat -vertices

Let be the set of -flat -vertices such that there exists an edge where and is a -flat -vertex. Let , and let .

Lemma 5.1.

.

Proof.

For , let denote the set of -flat -vertices contained in some edge where is a -flat -vertex. Since is a -flat -vertex and , . So, . Assume that .

We first describe a certain structure that all but vertices in are contained in. Let be an edge of with and a -flat -vertex. Since , . Hence , so by the case, . Let be a vertex such that . Since is -flat, note that is low.

Since and every vertex in is low (and thus has at most neighbors), Thus, if there are at least vertices in that are in a bad pair with , then we can find some such that is also a bad pair. Consider the non-edge . Since and are both bad pairs, there must be a -link that avoids . But since , there is no such link, a contradiction. Thus, there are at most vertices in that are in a bad pair with .

Let denote the set of vertices in that are in a good pair with . Then,

Assume now that , with and edges of with a -flat -vertex. Since is a good pair, there exist edges and forming a -link. Note that to avoid a in , we must have . Since , we have .

If , then consider the non-edge . Note that any link between two of the vertices in that does not contain the third cannot contain since every edge containing contains two vertices in . Thus, if there were such a link, say a -link with , then there would be a in consisting of this link and the edge , a contradiction. Thus, , so . For ease of notation, let us define .

Let denote the third edge of containing . We claim that . Indeed, by Claim 4.3. If , then the non-edge intersects every edge containing and in two vertices, and thus adding it to does not create a . If , then since , the edges , and form a in , a contradiction. Thus, as claimed. Note that this also implies that is a bad pair since any -link would necessarily use the edges and , but .

At this point, we define the configuration of to be the collection of vertices . We wish to speak of the configurations associated with multiple vertices from simultaneously, so given , we will let and denote the vertices in the configuration of playing the roles of and as described above. Note that while there is a unique choice of and , the vertices and are interchangeable, so we may arbitrarily choose which vertex in is and which is . We will label the configuration of as . We have proven the following about for any :

-

•

The edges and are all present in ,

-

•

The vertices and are all distinct, and

-

•

The pair is a bad pair.

Now, given a vertex and a vertex , note that is adjacent in to a vertex in if and only if either or are in . Since a vertex can play the role of or in at most one configuration, this implies that is adjacent to at most configurations.

We claim that for every , , and no other edges containing and one of or are in . Indeed, first consider the case where . Then is adjacent to at most configurations, so there exists a such that is not adjacent to . Consider the non-edge . Since is a bad pair, there must be a loose path of length from a vertex in to , but since is not adjacent to any vertex in , this is a contradiction. Thus, . Now consider the possibility that we have an edge for some . Then clearly , and so , and form a in , a contradiction. Thus, the only edge containing and is . By the symmetry between and , this also is the only edge containing and as claimed.

Now, given any , there are at most configurations adjacent to either or in , so there exists some such that neither or are adjacent to . Consider the non-edge , and a triangle in . By the choice of , cannot be a core vertex in , and thus is a good pair, but no edge of contains and exactly one of these vertices, so the -link, along with the edge gives a in , a contradiction.

Thus for each , . Therefore, . ∎

We will call a vertex supported if contains a edge, and unsupported otherwise. Let be the set of unsupported -flat -vertices adjacent to at least two -flat -vertices. Let , and let .

Lemma 5.2.

.

Proof.

Suppose . Let and and be -flat -neighbors of . Since is unsupported, and is contained in edges and , where , and and are -flat -vertices (possibly, some s and/or s coincide). In this case the set will be called the -set.

Since , and the pairs and are good. Since is a good pair, the codegree of either or is at least . On the other hand, since is -flat and is -flat and unsupported, the codegree of is . Thus the codegree of is at least . Similarly, the codegree of is at least . It follows that . If also , then , contradicting the fact that .

Let be the set of such that . Since , by the symmetry between and we may assume that .

Let . Since and are -flat, . This implies that is a bad pair. Since for every two distinct we can try to add the edge and the pairs and are bad, the pairs are good in . Since are low, the number of such that is adjacent to is at least

Denote the set of such (including our ) by .

If there is an edge containing both and , then there is a such that is not in the -set, and so has a triangle formed by and , a contradiction. Thus .

Now, if for some there is an edge containing and , then again there is a such that is not in the -set, and so has a triangle formed by and , a contradiction. Thus for each .

Consider again a . Since is a good pair, there are edges and forming a -link. In view of , . Let . Since the codegree of is , . It follows that and . So, we may assume .

We claim that

| (4) |

Indeed, suppose has edge . Since and are -flat, . Since codegree of is two, . But then has a triangle formed by and , a contradiction. This proves (4).

Let be obtained from by adding edge . Then must have a triangle formed by and some edges and . If the core vertices of are and , then in view of , . Let . Since the codegree of is , . But both edges in containing have two common vertices with , a contradiction. If the core vertices of are and , then we get a similar contradiction. Hence the core vertices of are and . Let . In view of , . By the symmetry between and , we may assume , say .

We claim that

| (5) |

Indeed, suppose has edge . By (4), . Since we know all edges incident to and , . But then has a triangle formed by and , a contradiction. This proves (5).

By the definition of and , is either or .

Case 1: , say . Then we know all edges incident to . Since , is not adjacent to , and and are low vertices not adjacent to (by (4) and (5)), there exists such that is at distance at least from .

Let be obtained from by adding edge . Then must have a triangle formed by and some edges and . By the choice of , the core vertices of in are and . Let contain . In view of , . We know all edges containing , in particular, we see that the codegree of is . Also, the only candidate for is . It follows that and . But we also know all edges containing , and none of them contains , a contradiction.

Case 2: , say . Again, we know all edges incident to . Let be obtained from by adding edge . Then must have a triangle formed by and some edges and .

Suppose first that the core vertices of in are and . Note that each of the edges and shares two vertices with . Thus the only candidates for and are and , but they have two common vertices, a contradiction.

Suppose now that the core vertices of in are and . Suppose that . Again, the only candidate for is . On the other hand, in view of , . Hence . But the third vertex of cannot be (by (4)) and cannot be because we know all neighbors of and is not in this list.

Finally, suppose now that the core vertices of in are and . Suppose that . Now the only candidate for is . Similarly to the previous paragraph, in view of , , and hence . Again, the third vertex of cannot be (now by (5)) and cannot be because we know all neighbors of , and is not in this list. This finishes the proof of the lemma. ∎

6 Lower Bound: Vertices of degree

The goal of this section is to provide the results necessary to show that almost all -vertices end up with charge at least . Note that -flat -vertices are automatically supported, and thus will receive charge at least , and -flat -vertices that are not supported should receive charge from each of their non-low neighbors, again leaving them satisfied. Thus, our main obstacle is -flat -vertices.

As a reminder to the reader, we expect a -flat -vertex to get charge from its non-low neighbor, and charge from two of its low neighbors, in particular, one low neighbor in each edge containing (possibly the same vertex twice if has a double neighbor ). One result which will be helpful is that there are almost no edges containing two -vertices. Indeed, from Corollary 4.13 we already know each edge has two vertices in . Now we will show there are almost no edges.

6.1 Edges of type

For , we will say that a vertex with is a -far neighbor of a vertex if , and

-

1.

for each edge containing either or ; and

-

2.

for each edge containing , the degree in of each vertex of is at most

Let be the set of -far neighbors of vertices in . Let , and let .

Claim 6.1.

For each every has at most -far neighbors. Consequently,

Proof.

Suppose, has at least -far neighbors, and is one of them. Let be in edges of the form , where is also a -far neighbor of . Note that by Property (1) in the definition of -far, is only adjacent to other -far neighbors of through edges that contain . Since , has at most neighbors in . By Property (1), all these neighbors are not -far neighbors of , and again by Property 2, each of them is a neighbor of at most other -far neighbors of . There are at least

-far neighbors of at distance at least from in , and since there are at most -far neighbors of adjacent to in , there exists at least one -far neighbor of that is not adjacent to in , and is distance at least from in . Let be one such -far neighbor of .

Let and . Assume that together with edges and form a triangle in . If the core vertices of in are and , then and are at distance at most in , a contradiction to the choice of .

So by the symmetry between and , assume without loss of generality that the core vertices of in are and , and the edge of contains . But then one of the vertices in is in , a contradiction to Property (1) in the definition of -far. ∎

Lemma 6.2.

All vertices of every edge are in .

Proof.

Let , where , and . Since not all vertices of are in , neither of and is in . Then and are not in and hence are -flat. So, there are vertices such that and . By Claim 4.4, , and . By Claim 4.3, cannot be a double neighbor with both and , so assume that .

Since some vertex of is not in , cannot be a -far neighbor of , so . Let be the other edge containing in , and let be an edge that contains and . Since , , so for , , and to not be a triangle in , we must have that . Let be the second edge containing , and note that may be equal to .

Consider the edge , and note that since and are not adjacent. Then contains a , say . Note that is a bad pair by Claim 4.5 since is not a double neighbor of either vertex. Thus, is one of the core vertices of . This implies that either or is an edge of . If is such edge, then must be in an edge with one of or , but not both; this is a contradiction though as this edge, along with and would give us a in . If is an edge of , then we must have an edge in containing exactly one vertex from and exactly one vertex from . Furthermore, since and so . Consider two cases based on if or not.

Case 1: . In this case, if contains and a vertex from , this gives us a triangle in with edges and . If contains and a vertex from , then this also gives us a triangle in , this time with edges and . Thus, we reach a contradiction.

Case 2: . Note that since is not a -far neighbor of , , we have some edge containing both and . Since in this case does not have any double neighbors, and or , for the edges and to not form a triangle in , we must have that . Now, since , the only possible way that and do not form a triangle is if , but in this case, and give us a triangle, and so we reach a contradiction. ∎

6.2 Helpful and Half-Helpful Vertices

We now provide definitions which will help us deal with -vertices.

Given vertices and , we will call the pair rich if , and we will call a vertex rich if is in any rich pair. We will call a edge with and exceptional if

-

•

and , and

-

•

is a rich pair and .

We will call the exception in the exceptional edge .

We now classify all edges of into three mutually exclusive types: needy edges, rich edges and reasonable edges.

Needy Edges:

Let be a edge with . We will say is a needy edge with recipient if is either a -vertex or a -flat -vertex, and is not.

Rich Edges:

Let be a edge with that is not needy. We will say is a rich edge with recipient if

-

1.

is not exceptional,

-

2.

, is unsupported, and is not rich, and

-

3.

at least one of the following occurs:

-

•

is a rich pair,

-

•

and is supported, or

-

•

.

-

•

Reasonable Edges:

We will call all edges that are not needy or rich, reasonable.

Helpful and Half-Helpful Vertices:

We now can turn our attention to the low vertices which will give charge to -flat -vertices. Given a low vertex let denote the number of rich edges in which is the recipient, let denote the number of reasonable edges containing , and let denote the number of edges, and finally let be the number of edges containing and a -flat -vertex.

Then, a low vertex of degree at least is helpful if

| (6) |

The left-hand side of (6) will be exactly the amount of charge ends up with before gives any charge away. Then, the right-hand side is the amount of charge we want to be able to give away, plus the amount of charge we want to keep (namely ). So, helpful vertices are exactly those low vertices that can give charge to each of their -flat -neighbors (counted with multiplicity), and still have charge at least .

Since (almost) every edge contains at most one -flat -vertex, it would be nice if we could simply show that every edge containing a -flat -vertex also contains a helpful vertex, however it is not clear if this is the case. Instead, we will do a second round of “helping”. We call a low vertex a -donor if is in exactly edges with -flat -vertices which are either type or are type , where the other low vertex is not helpful. Let denote the value of for which is a -donor.

A low vertex of degree at least is half-helpful if

| (7) |

Again, the left-hand side of the above inequality is exactly the charge that has before it gives any away, and the right-hand side is the amount of charge we want to give away, along with the charge we want to keep. Note that since , every helpful vertex is also half-helpful.

We now will show that almost every edge containing a -flat -vertex contains either a helpful or half-helpful vertex. In particular, we will show the following:

-

•

Almost every edge containing a -flat -vertex contains a vertex of degree at least , and

-

•

Almost every vertex of degree at least is helpful or half-helpful.

As we have already shown that there are almost no or edges, to prove the first bullet point above, we need to only deal with edges.

Lemma 6.3.

Let be an edge with a -flat -vertex . If , then .

Proof.

Suppose and . Then no vertex of is in . By Lemma 6.2, . Since is not in , it is contained in a high edge , say . Since is not in , is a good pair. To avoid a in , each -link must contain , say, is an edge of . Consider the non-edges and . Since these triples intersect every edge containing in two vertices, there is an -link and a -link avoiding the vertex .

Assume that there exist distinct vertices such that there is a -link that has no edge containing both and . Thus there exist vertices and such that and are edges in (note that must be in this second edge to avoid a triangle with ). However, then , and form a in , a contradiction.

Thus, and are edges for some such that . We will consider cases based on whether or not.

Case 1: . Under this assumption, and . By Claim 4.3, we must have , and furthermore, . Thus by Claim 4.5, is a bad pair. Consider the non-edge . There must be an -link or an -link in . However every edge containing or intersects in two vertices, so no such links exist. This proves the case.

Case 2: . Note that we may have . Consider the non-edge . The only edges containing or that do not intersect in two vertices are and . Thus, cannot be the pair of core vertices in the in , so must, and there has to be an edge in of the form for some , . If , then , and form a in , so we must have . Furthermore, if , then , and form a in , so . Furthermore, note that there is no edge in containing exactly one vertex from and exactly one from since any such edge could not contain , and thus would create a in with and . Similarly, there is no edge containing and exactly one vertex from .

Since has no double neighbors, by Claim 4.5, is a bad pair. Consider the non-edge . There must be a -link for some . This link cannot use edge since no edge involving can complete the path, and there is no edge in containing and exactly one vertex from . Similarly, the link cannot use the edge since there is no edge containing exactly one vertex from and one from . This contradiction completes the proof. ∎

Now we focus on showing that almost all low vertices of degree at least are half-helpful. Vertices of degree or more and supported vertices are relatively easy to deal with, but first we need a helpful lemma.

Lemma 6.4.

Let be a edge where and is a -flat -vertex. If neither nor is supported or belongs to , then .

Proof.

Since is -flat and not in , is a good pair. We will consider two cases based on if or not.

Case 1: . For to be a good pair and to avoid a triangle with , there must be edges and for some .

Consider the non-edge . Since intersects every edge containing in two vertices, must be a good pair, and furthermore, this -link must avoid . Furthermore, this link must use to avoid a in with . If one of the edges of the link is for some , then we are done since , so let us assume otherwise. Then the loose path must use edges of the form and for some , but then , and form a in , a contradiction.

Case 2: , say is an edge of with . Since is not in , the codegree of must be at least , say is an edge.

First, if , then the non-edge intersects every edge of in at least two vertices, so is a good pair. Any -link must contain to avoid a in with , but if one of the edges in this link contains both and , then , satisfying the hypothesis of the lemma, so we may assume that one of the edges in this path is and another is for some . However, this creates a in with edges , and . Thus, we may assume .

Now consider the non-edge . Since it intersects both edges containing in two vertices, must be a good pair, and there must be a -link that avoids . Furthermore, this link must contain to avoid a in with the edge . If this link contains an edge containing both and , this would satisfy the claim of the lemma, so the link consists of edges of the form and for some . But this gives a in with edges , and , a contradiction. ∎

Lemma 6.5.

Let and . If is supported or , then is helpful.

Proof.

Suppose now that some vertex with is not helpful. By above, Similarly, if is contained in a reasonable edge or is a recipient in a rich edge, then this edge does not contain a -flat -vertex, and hence

which again yields (6). Thus

| (8) |

Since , there are a vertex and a vertex such that is an edge in .

Case 1: . By Lemma 4.9, either is contained in an edge where is neither a -vertex nor a -flat -vertex, or , in which case

and hence (6) holds. Thus, assume the former. Since , is either reasonable or rich. By (8), we conclude that is a rich pair. Since , . Thus, if is not helpful, then

| and each edge containing apart from contains a -flat -vertex. | (9) |

In particular, since is a rich pair, we have edges and where and are -flat -vertices.

Then the pair cannot be good: the first edge of any -link must contain at least one of and . Since , is adjacent to another vertex in , say has an edge where . By (9), must be a -flat -vertex, thus . Then by Lemma 6.4, , so by Lemma 4.9 some edge containing does not contain -flat -vertices. This contradicts (9).

Case 2: . Since , . Then is not -flat. Thus, is a -flat -vertex. Since , the co-degree of is 1. If , say , then and we are done. So , and hence is a bad pair.

Since , is adjacent to a vertex distinct from , say . If is not a -flat -vertex, then and we are done again. Suppose is a -flat -vertex. Since , . Then by Lemma 4.9, some edge containing does not contain -flat -vertices, and we again get . ∎

Let be the set of -flat -vertices that are double neighbors with an unsupported -vertex not in . Let , and let .

Lemma 6.6.

.

Proof.

Each -flat -vertex in is adjacent to or . For , let be the set of edges such that is an unsupported -vertex, is a -flat -vertex, and . By Lemma 6.4, for each such . Choose one such edge . Let be the other edge containing , and and be other edges containing . We consider cases based on whether or not.

Case 1: For at least edges , , say . Let be obtained from by adding the non-edge . By definition, has a triangle formed by and, say and . Since both edges in containing have two common vertices with , the core vertices of in are and , say .

In order for and not to form a triangle in , we need . If , then , and the edges and form a triangle in , a contradiction. Thus we may assume . Similarly, if , then , and the edges and form a triangle in , a contradiction again. So we may assume , and in particular, . Thus the edges containing are .

Case 1.1: For some , is a good pair, say edges and form a -link. In order to avoid triangles, must contain and . Since we know all edges containing or , the only possibility for this is that . But then, since , the edges and form a triangle in .

Case 1.2: is a bad pair for at least edges with . We can try to add the edge for each two such edges and . By the case, the core vertices in each obtained triangle should be always and . Since is unsupported, all vertices are low. So the common neighbor of with most of should be , which then must participate in at least configurations for corresponding .

Case 1.2.1: This is adjacent to , say . Since each is low, there is a configuration in which . For this configuration, will have a triangle with edges and , a contradiction.

Case 1.2.2: This is not adjacent to . Let be obtained from by adding new edge . By definition, has a triangle formed by and, say and .

If the core vertices of were and , then the edge of containing , say can be only and hence . Since we know all edges containing and each of and shares two vertices with , if , then the only candidate for is , but it shares two vertices with , a contradiction. Thus in this case , say . Since is not adjacent to , . Hence and form a triangle, a contradiction.

If the core vertices of were and , then again the edge containing can be only and hence . Again, if , then the only candidate for is , but it shares two vertices with , a contradiction. So, again , say . Since and , . Then and form a triangle in .

The last possibility is that the core vertices of are and . We may assume that . Because of , . We know all edges containing and among these edges only contains . Hence . In this case, the only candidate for is , and so . Thus as in the previous paragraph we may assume . Since , . And we know all edges containing , so . Again, and form a triangle in . This finishes Case 1.

Case 2: For at least edges , and . Let an edge containing and be . If , then edges and form a triangle. If , then we have Case 1 with in the role of . So, .

Let be obtained from by adding edge . By definition, has a triangle formed by and, say and . Since both edges in containing have two common vertices with , the core vertices of in are and . We may assume . Because of , . Suppose , say . Since shares only one vertex with , . Since Case 1 is already covered, . Then edges and form a triangle. This contradiction implies . In this case, edges and form a triangle. This finishes Case 2.

Case 3: For at least edges , and . As in Case 2, let be obtained from by adding edge . By definition, has a triangle formed by and, say and . Again, the core vertices of in are and . We may assume . Again, . If , then edges and form a triangle. So, we may assume that .

By the case, has no edges and . Hence is a bad pair, and we have at least such edges containing . We can try to add the edge for each two such edges. Since pairs and are bad, the core vertices in each obtained triangle should be always and . So most of these vertices must have a common neighbor, say (of high degree). Since is unsupported and is -flat, all vertices are low and so . Let the edge containing and be . Now we know all edges containing apart from the fact that we do not know whether is one of or .

If is adjacent to , then we simply repeat the argument of Subcase 1.2.1. So below we assume

| (10) |

Case 3.1: . Then let be obtained from by adding edge . By definition, has a triangle formed by and, say and . Again, the core vertices of in are and . We may assume . Now . Since we know all edges containing and three of these edges have common vertices with , the only candidates for are and . Neither of them contains , so . The common vertex of and cannot be because , so by symmetry, we may assume that . Then edges and form a triangle.

Case 3.2: , but there is an edge containing and , say . If , then edges and form a triangle, so suppose . Furthermore, if for some , then edges and form a triangle. So below we assume

| (11) |

As in Case 3.1, consider obtained from by adding edge . Again, has a triangle formed by and, say and . Again, the core vertices of in are and . We may assume . Now . Since we know all edges containing and three of these edges have common vertices with , the only candidates for are and . By (11), neither of them contains , so . The common vertex of and cannot be because , so by symmetry, we may assume that .

We claim that

| (12) |

Indeed, suppose there is an edge . Since , . Since we know all neighbors of and , we know that . Then edges and form a triangle. This contradiction proves (12).

Now, consider obtained from by adding edge . Again, has a triangle formed by and, say and . Suppose first that is a core vertex of and . Then . So, the vertex is one of or . Since the only edge containing and at least one of and is , and it has two common vertices with , . By (10) and (12), . So, . But must have exactly one common vertex with . Then edges and form a triangle. Therefore, the core vertices of are and .

We may assume . Since the codegree of is at least , . But is not in an edge in which one vertex is in and the other is in . This contradiction finishes Case 3.2.

Case 3.3: . Note that and are the only high vertices adjacent to or . We have at least such configurations containing . Fix one such configuration. Among the remaining similar configurations with the same vertices and , find one with vertices such that the distance from to is at least (we can do it because is not adjacent to or ). Consider obtained from by adding edge . Again, has a triangle formed by and, say and . By the choice of , it cannot be a core vertex, so and must be. But both edges containing share two vertices with . This contradiction shows that there are less than edges with and .

Together with Cases 1 and 2, this implies that for . This proves the lemma. ∎

Lemma 6.7.

Let . Then for every edge such that neither of and is supported, , and , we have .

Proof.

Suppose contains edges and such that , , , and neither of and is supported.

Since ,

| (13) |

Case 1: There is an edge containing . Let . By (13), . Let . Then has a triangle containing . Since both and have two common vertices with , there is an -link avoiding formed by some edges and , say . In view of , , but since , . Thus , and hence and form also an -link. Then together with they form a triangle in , a contradiction.

Case 2: Since , , and there is an edge . By Case 1, , and is not in . Let . Then has a triangle containing . Since both and contain , there is a -link avoiding , say with edges and where . In view of , , but since , . Thus , and hence and form also a -link. Then together with they form a triangle in , a contradiction.

Case 3: Cases 1 and 2 do not hold. If the pair is good, then because of , the degree of or of would be at least . But by (13) and Case 2, neither holds. Hence is a bad pair.

Suppose now is good. Let and be the two edges of a -link in with . In view of , , but since Case 2 does not hold, . Thus , and the common vertex of and is . But then Case 1 holds, a contradiction.

Since both pairs and are bad and , by Lemma 4.10, there is a pair of vertices distinct from such that and . By the case, . Consider again . One of the pairs contained in must be good.

If is good, then in view of either or . The former inequality is Case 2 and the latter is the claim of our lemma. If is good and and are the two edges of a -link in with , then in view of , , but since , . Thus , and hence and form a -link. Then together with they form a triangle in , a contradiction.

The last possibility is that is good. Let and be the two edges of a -link in with . Then, since shares two vertices with , . By the symmetry between and , we may assume that . If , then has a triangle with the edges and . Finally, if , then has a triangle with the edges and . ∎

Lemma 6.8.

No unsupported -vertex is a double neighbor of a -flat -vertex.

Proof.

Suppose an unsupported -vertex is a double neighbor of a -flat -vertex , say , where and . By Lemma 6.4, , and since , . Let and be the other two edges containing and , possibly .

Since , is a good pair. Since is the only edge containing but not , this edge must be in each -link. Furthermore, to avoid a in with any of the edges , and , each -link must contain all , , and . This implies that actually . Assume without loss of generality . The second edge of this path must be .

Consider the non-edge . Since this non-edge intersects every edge containing in two vertices, there must be an -link that avoids . To avoid a in with the edge , this link must contain . The only edge of that contains , does not contain , and does not contain both and is . Furthermore, the second edge in this path must be for some , but then the edges , and form a in , a contradiction. ∎

Lemma 6.9.

Let and . If is a rich pair, then is helpful.

Proof.

Since is rich, . Let , and be edges in . If is supported or , then by Lemma 6.5, is helpful. So we assume is unsupported and . Since , , thus . We will consider cases based on the degree of and whether is a good pair or a bad pair.

Case 1: is a good pair. Since is a good pair, there is an -link, and it must contain the vertices and . By symmetry, we can assume the link contains the edges and . This implies that neither nor is -flat. Since , by the definition of (when ) or Lemma 6.8 (when , is not a -flat -vertex. It follows that none of contains a -flat vertex and hence . Then (6) holds.

Case 2: is a bad pair and . By Lemma 4.9, one of the vertices is not a -flat -vertex. Since , is adjacent to some other vertex , say , where , but may be one of the ’s. Since , .

Case 2.1: . By Lemma 4.9, either both edges containing and are not -flat -vertices, implying , or at least one of the edges containing and is either reasonable or rich with recipient , so and . In either case, (6) holds, so is helpful.

Case 2.2: . If is reasonable or rich with recipient , then , while , so (6) holds. Thus must contain either a -vertex or a -flat -vertex. However since , cannot be -flat, so must be a -flat -vertex. This implies .

Suppose first that is an edge, say . In this case, , so by Lemma 4.9, is contained in at least one edge that does not contain a -flat -vertex and is not . This implies that , so (6) holds. Thus is not an edge.

If , then since is a -flat -vertex, again , and so (6) holds. Thus . In this case, since , and are bad pairs. So by Lemma 4.10, there exist vertices such that and are edges. Since is -flat, one of or must be in , say . Furthermore, since and , . So is either reasonable or rich with recipient . In either case, while (as neither nor contain a -flat -vertex), so (6) holds, i.e., is helpful.

Case 3: is a bad pair and . Since , is adjacent to a vertex in that is not , say is an edge, where . Since and , cannot be -flat.

Case 3.1: is a -flat -vertex. We claim that

| and are bad pairs. | (14) |

Indeed, since and , . Hence if , then by Claim 4.5, and are bad pairs.

Suppose now , say . Then and are not adjacent since any edge containing and cannot contain or and misses one of or , so such an edge would create a in with and either or . If there was an -link, it would have to use the edge , but there is no edge connecting or to that does not contain . Thus is bad. If there was an -link, then it would contain to avoid a in with the edge , and so the edge must be contained in the path, but since and are not adjacent, there is no edge that can connect to one of or that does not contain . Thus, is also bad. This proves (14).

Since , by (14), there exist edges and for some . As we already know all edges containing , for some , assume without loss of generality . Then consider the non-edge , and note that this intersects both edges containing in two vertices, so there should be an -link. But is a bad pair, a contradiction.

Case 3.2: is not a -flat -vertex. Then is either reasonable or rich with recipient . By Lemma 4.9, one of the vertices is not a -flat -vertex, so , and . Thus, (6) holds unless , , and . By symmetry, assume that is not a -flat -vertex, while and are. By Lemma 6.8, . Furthermore, Since , an are good pairs. Consider first an -link. To avoid a in with , must be in this link. Since , either or must be in this link, but if was in this link, then the second edge would need to contain and , which contradicts Lemma 6.2. Thus, the -link must contain the edge and an edge . Similarly, there is an -link containing the edges and for some vertices and , possibly equal. This gives us all the edges incident with or .

Consider the non-edge , and let be a in . Note that and cannot both be core vertices in since the only edges containing or that do not contain two vertices in are and , which share two vertices. Thus, is a core vertex in , and we may assume by symmetry that is as well. Since is a core vertex, must be an edge of , which implies that is in an edge containing one of or , but not both. If is in an edge containing but not , this edge must be (i.e. ), but then , and form a in , a contradiction. So there must be an edge containing and , but not . This implies that . If , then is a rich pair so is reasonable, which makes , giving us that helpful. Similarly, if , then is exceptional and thus reasonable, so again is helpful. ∎

Claim 6.10.

Let be an exceptional edge such that , and is the exception in this edge. Then is helpful.

Proof.

Let be the second edge in that contains and , and let and be the remaining edges of that contain the rich pair , and note that and must be -flat -vertices. By Lemma 6.8, . If at least one of and is a bad pair, then some of and is in . In this case, and hence , a contradiction. Thus and are good pairs. Since Lemma 6.2 implies that and are not adjacent, and any -link must contain to avoid a in with the edge , any -link must use the edge and an edge . Similarly, any -link must use the edge and an edge . We claim that . If , then , and for a in , a contradiction. Similarly if , then , and form a in , again a contradiction. Thus, . This implies that . We will consider cases based on .

Case 1: . Then is either reasonable or rich with recipient . Along with the reasonable edge , this gives us that , while , which along with is sufficient to satisfy (6), so is helpful.

Lemma 6.11.

All -flat -vertices outside of are helpful.

Proof.

Suppose there is a -flat -vertex that is not helpful. By Lemma 6.5, is unsupported. By Lemma 6.9 and Claim 6.10, we can assume is not rich or exceptional. Furthermore, by Lemma 6.4, any non-low edge containing must not contain a -flat -vertex, since this would imply is rich. Thus, if is -flat, then , and (6) is satisfied. Thus, we may assume is -flat. Furthermore, since , if is in at least one reasonable edge or a rich edge with recipient , then (6) is satisfied, so we must have . We will consider cases based on if has one or two neighbors in .

Case 1: There exists a vertex such that . Let and be edges of . Note that neither nor are -flat -vertices, and furthermore by Lemma 6.7, and are not -flat -vertices. Then since , and must be -flat -vertices. Note that if is an edge, then , and hence is helpful, so .

Since is -flat, by the case, is the only non-low neighbor of , so by Lemma 4.6 must be a good pair. Any -link must contain both and , but is not an edge of , so the edge in that contains must contain or , contradicting the fact that they both are -flat.

Case 2: There exist distinct vertices such that . Let and be edges in , noting that we may have . Since , cannot be -flat, and so is a -flat -vertex. Similarly, is a -flat -vertex.

Case 2.1: . Let , and be the low edges containing with , and being -flat -vertices. Note that while all are distinct, the ’s do not need be. First consider if for some . In this case, consider the non-edge . It intersects all edges containing in two vertices, so there is a -link . Let be the edge of this link containing , and note that the second edge must be of the form since and are not adjacent by Lemma 6.2 and the fact that and are not in . However, in this case, , and form a in , where all these vertices are distinct because , and must actually be a vertex in . Thus, we cannot have for any . This implies that . In this case, consider the non-edge . It intersects every edge containing or in at least two vertices, so adding this non-edge cannot create a in , a contradiction.

Case 2.2: . In this case, , so by Claim 4.5, and are bad pairs. Then since , there exist vertices such that and are edges in . Since is -flat and is a -flat -vertex, must be the edge . But then , which contradicts the fact that . ∎

Lemma 6.12.

All -flat -vertices outside of are helpful.

Proof.

Suppose there is a -flat -vertex that is not helpful. By Lemma 6.5, is unsupported. By Lemma 6.9 and Claim 6.10, we are done if is rich or exceptional, so we may assume is neither. Let be a neighbor of .

Case 1: is -flat. In this case, is only in high edges, so if has a -flat -neighbor, is rich by Lemma 6.4, contradicting our earlier assumption. Thus has no -flat -neighbors, and is trivially helpful.

Case 2: is -flat. Since is not special, it has a neighbor . If is the only non-low neighbor of , then is a rich pair, and we are done by Lemma 6.9. Thus assume is adjacent to at least two vertices in , and consequently for some (possibly ), say is an edge for some . Furthermore, none of the non-low edges containing can contain a -flat -vertex, so only the single low edge containing may contain a -flat -vertex. Thus, since is not helpful, and . This implies that is either a -vertex or a -flat vertex, but since , is not -flat. So is a -flat -vertex. By Claim 6.7 , and by Claim 4.3 , so by Claim 4.5, and are bad pairs. Thus since , there exist vertices and such that and are edges. Since is -flat, one of and is in , say . Then by Claim 4.3 since , and thus edge is either reasonable or rich with recipient . In both cases we get a contradiction with the fact that .

Case 3: is -flat and . Let and be the edges of containing and .

Case 3.1: . Then neither nor is -flat. Moreover, since , . Thus, the edges and are either reasonable or rich with recipient , so we have . Then (6) holds and is helpful. Thus, below we assume .

Case 3.2: . Since is unsupported, by Lemma 6.8 neither nor has degree .

Suppose both and are -flat -vertices. Since , and . Hence . Since , is a good pair, and any -link needs to contain to avoid a in . The only edges containing that could be in this link are and . Edge cannot be there since neither nor is in an edge with that contains only one of these vertices, and if is in this link, then the other edge of the link must be for some . But then the non-edge intersects all edges containing either or in at least two vertices, so neither can be a core vertex in the in , a contradiction. Thus, at least one of or is not a -flat -vertex, say is not.

Then is either reasonable or a rich edge with recipient , and since , and all do not contain a -flat -vertex. Thus is helpful since , i.e., (6) is satisfied.

Case 3.2: . Since , is a good pair. In particular, there is an -link, say with edges and , where and . To avoid a in with and , and must both be in this link. Since , we can assume without loss of generality that and for some .

If is a -flat -vertex, consider the non-edge . Since this non-edge intersects all edges containing in two vertices, there is an -link that avoids . Again, this link must contain and to avoid a in . If this link has edges and for , then so is not a -vertex or -flat -vertex, and . So by Claim 4.3, since , and thus the edges and are either rich with recipient or reasonable. The other possible -link that avoids is a path with edges and for some . In this case, and , so since , and are not -vertices. Since they also are not -flat, and are either rich with recipient or reasonable. Furthermore, in either of these two cases, , so is helpful since implies (6). Thus, we are done if is a -flat -vertex.

If is not a -flat -vertex, then , and since and , is not a -vertex and not -flat. So is either rich with recipient or reasonable. Therefore, again is helpful since .

Case 4: is -flat and not a double neighbor with any vertices in . Let be neighbors of and let and be edges in . If either of these edges are rich with recipient or if both of them are reasonable, then , and so is helpful. Thus we may assume at least one of or is either a -vertex or a -flat -vertex, assume is such a vertex. Since and since , is not -flat, and thus must be a -flat -vertex.

Case 4.1: . For to not be helpful, we must have . Let be a low edge containing with a -flat -vertex, and let be the other low edge containing . Note that , and by Lemma 6.8, . Consider the non-edge . Since this non-edge intersects every edge containing in two vertices, there a -link. The only edge containing that can be in this link is . So the other edge must connect or to , say this edge is (note that since is adjacent to some vertex in ), but then we may assume since otherwise , and form a in . Then consider the non-edge , and note that this non-edge intersects every edge containing either or in two vertices, so adding to does not create a , a contradiction.

Case 4.2: . Since , , so by Claim 4.5, and are bad pairs, and thus since , there exist vertices such that and are edges of . Since is -flat and is a -flat -vertex, must be the edge . This implies that . If or if , then , and , so (6) holds. On the other hand, if and , then this contradicts Lemma 6.7. ∎

Let be the set of -flat -vertices such that the low edge containing satisfies the following:

-

(a)

none of or is in ;

-

(b)

for some , is a -flat unsupported -vertex;

-

(c)

is not helpful;

-

(d)

the high vertex adjacent to is distinct from the high vertex adjacent to .

Let , and let .

Lemma 6.13.

.

Proof.

Let be the set of low edges satisfying (a)–(d) for some -flat -vertex . Let be the set of edges in where and . If the lemma does not hold, then by the symmetry between and , we may assume that . For , let be the unique high edge containing and be the unique high edge containing . By Lemma 6.4,

| is rich or supported. | (15) |

So if , then is rich or supported, and thus helpful by either Lemma 6.9 or Lemma 6.5, contradicting (c). So, . Since , . If , then since , the edges and form a triangle, a contradiction. Thus, .

Since , is a good pair. Let edges and form a -link. Since , . Since , has the form for some vertex . If , then and form a triangle in . Hence . Since each of and contains only one vertex in , (15) yields that .

If , then is a -flat vertex with (because of and ) and (by (15)). Moreover, if , then is reasonable. This contradicts the condition that is not helpful. Thus .