Solar Neutrinos and the Decaying Neutrino Hypothesis

Abstract

We explore, mostly using data from solar neutrino experiments, the hypothesis that the neutrino mass eigenstates are unstable. We find that, by combining 8B solar neutrino data with those on 7Be and lower-energy solar neutrinos, one obtains a mostly model-independent bound on both the and lifetimes. We comment on whether a nonzero neutrino decay width can improve the compatibility of the solar neutrino data with the massive neutrino hypothesis.

The discovery of distinct nonzero neutrino masses and nontrivial lepton mixing opened the door to several fundamental questions that revolve around the properties of the neutral leptons. Here we concentrate on what, experimentally and model-independently, is known about the neutrino lifetime.

In the absence of interactions and degrees of freedom beyond those of the Standard Model, the two heaviest neutrinos – and ( and ) in the case of the so-called normal (inverted) neutrino mass hierarchy Agashe:2014kda – are unstable, decaying into lighter neutrinos and photons ( or , where ). The associated lifetimes, given the tiny neutrino masses, are longer than years – much longer than the age of the universe. The presence of new interactions, degrees of freedom, etc., can, of course, change the picture dramatically.

Experimental bounds on the lifetimes of the neutrinos are much shorter than those expected from the Standard Model minimally augmented to include nonzero neutrino masses. Consulting ‘The Review of Particle Physics’ Agashe:2014kda , one encounters different bounds that span almost twenty orders of magnitude. Bounds on the neutrino magnetic moment, for example, translate into bounds on radiative neutrino decays Broggini:2012df . Results from cosmic surveys sensitive to the expansion rate of the universe at different epochs are consistent with the existence of around three independent neutrino states, naively indicating that these do not decay within the span of billions of years. In order to translate measurements of the expansion rate of the universe into a bound on the neutrino lifetime, however, one must consider the nature of the neutrino decay process, since the daughters of the putative decay also contribute to the expansion rate of the universe and could, in principle, mimic the contributions of their parents Beacom:2004yd ; Hannestad:2005ex . The observation of the effects of nonzero neutrino masses in cosmic surveys might change the picture significantly Serpico:2007pt .

Model-independent bounds exist from experiments where the number of neutrinos produced in the source can be compared to the number of neutrinos detected some distance away. These include all neutrino oscillation experiments. Given a baseline and a “beam” energy , one expects to be sensitive to a neutrino decay width for with mass such that

| (1) |

Here, for convenience, we define , which has dimensions of energy-squared, for two reasons. On one hand, all bounds discussed here are sensitive to : it is not possible to disentangle the neutrino mass from its decay width, both being unknown. On the other hand, , measured in eV2, can be easily and directly compared to the neutrino mass-squared differences that are measured in neutrino oscillation experiments and “compete” with the decay effects. For conversion purposes, eV2 translates into a lifetime s for a neutrino with mass eV.

Using Eq. (1), it is easy to naively estimate that long-baseline accelerator experiments like MINOS, T2K, and NoA, with km/GeV, are sensitive to eV2, atmospheric neutrino experiments like SuperKamiokande, with km/GeV, are sensitive to eV2, and the KamLAND reactor neutrino experiment, with km/GeV, is sensitive to eV2. Detailed analyses of atmospheric and MINOS data, for example, translate into eV2 GonzalezGarcia:2008ru and eV2 Gomes:2014yua , respectively, assuming .

Astrophysical neutrinos, when directly observed in Earth-bound detectors, provide significantly more stringent bounds on some of the . The observation of neutrinos from Supernova 1987A implies that at least one of the neutrino mass eigenstates made it from the explosion to the Earth and can be translated into eV2 for at least one Frieman:1987as . A very strong bound on at least one of the can also be derived Beacom:2002vi ; Meloni:2006gv ; Baerwald:2012kc ; Pakvasa:2012db ; Dorame:2013lka ; Fu:2014gja from the current and future observations of ultra-high-energy neutrinos using the IceCube detector Aartsen:2013bka .

Solar neutrinos have km/GeV and hence are sensitive to eV2. The authors of Beacom:2002cb were the first to point out that the 8B solar neutrino data translate into a very robust bound on eV2, mostly independent from and . In this letter, we revisit the impact of decaying neutrinos on solar neutrino data. Since the publication of Beacom:2002cb , our understanding of solar neutrinos and neutrino properties improved significantly. More and more precise KamLAND data not only confirmed the neutrino oscillation interpretation of solar neutrino data, but also provided a precision measurement of the “solar” mass-squared difference, , and a good independent measurement of the “solar” mixing angle Gando:2010aa . Borexino data allow a precision measurement of 7Be solar neutrinos, and a clean measurement of the solar neutrinos Bellini:2011rx . Finally, recent reactor An:2013zwz ; Ahn:2012nd ; Abe:2012tg and accelerator data Abe:2013hdq have measured the “reactor angle” , revealing that it is nonzero but quite small, . We will argue that all this information allows one to place, almost model-independently, bounds on both and from solar neutrino data. These results, when combined with results from atmospheric neutrinos, allow one to unambiguously place bounds on all three , , which are robust, mostly model independent, and do not depend on the values of the neutrino masses or the neutrino mass hierarchy.

We will show, a posteriori, that decay effects are negligible for the values probed by the KamLAND experiment. This implies that the oscillation results obtained from KamLAND apply even if the neutrinos have a finite lifetime, including the fact that eV2 and . This in turn implies that neutrino oscillations from the core to the edge of the Sun, to a very good approximation, satisfy the adiabatic approximation. Ignoring the (very small) day–night effect but taking into account that the different neutrinos can decay into final states not accessible to the different solar neutrino detectors, the probability that a neutrino with energy born in the Sun as a is detected as a , one astronomical unit away from the Sun is

| (2) |

where , , are the elements of the neutrino mixing matrix, while are the probabilities that the neutrino exits the Sun as neutrino mass eigenstates. Strictly speaking, Eq. (2) is a good approximation when where is the average solar radius. We will show that this is indeed the case for and , and we argue in the next paragraph that solar data are not sensitive to effects.

Given that eV2 – even if one includes nonzero neutrino decay widths GonzalezGarcia:2008ru ; Gomes:2014yua – for all relevant solar neutrino energies, . Since is small, given the precision of the solar neutrino data, related effects are irrelevant. In other words, the solar data are consistent with all values. We anticipate that effects impact only very modestly the constraints on the other oscillation and decay parameters. Henceforth, we ignore effects – we formally set it to zero – and treat solar neutrino oscillations as if there were only two neutrinos, and ( for active).

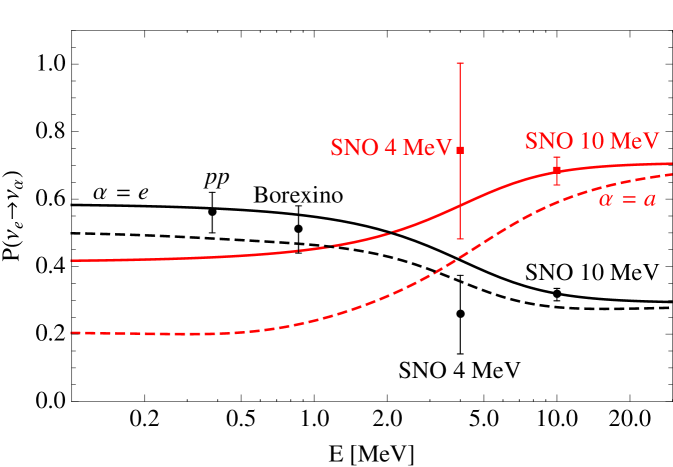

At high solar neutrino energies, MeV, , , such that and . 8B solar neutrino data are hence very sensitive to but have little sensitivity to Beacom:2002cb . The most recent solar data from SNO Aharmim:2011vm indicate a that decreases slowly as the neutrino energy decreases (as opposed to increasing, as predicted by the standard scenario, ), a fact that is consistent with a judicious choice of . For illustrative purposes, Fig. 1 depicts and as a function of , for , eV2, , and or eV2.

At low solar neutrino energies, MeV, solar neutrino oscillations are well approximated by simple, averaged-out vacuum oscillations such that , , and and . 7Be and solar neutrino measurements are hence sensitive to both and . In isolation, the low-energy solar neutrino data can be used to place a bound on either or , but not both. This is easy to see: the data are consistent with or as long as one judiciously chooses . For example, in the limit, say, , and can be made to fit the data, roughly, Bellini:2011rx , by choosing (in the “dark side” de Gouvea:2000cq ), which is consistent with data from KamLAND Gando:2010aa . This possibility, however, is ruled out by 8B data, which “require” .

In summary, combined low and high energy solar neutrino data allow one to place nontrivial bounds on both and , i.e., the possibility that either or is ruled out. is mostly constrained by the 8B data, while is mostly constrained by the 7Be and data. Given the order-of-magnitude difference between the neutrino energies, we anticipate the bound to be, roughly, an order of magnitude stronger than the bound.

In order to estimate the upper bounds on and , we perform a simple fit to , fixing eV2, the best fit from KamLAND, and setting , as discussed earlier. Given that KamLAND provides the dominant contribution to the measurement of , this is a very reasonable approximation. Since in the decaying-neutrinos scenario , we need to consider separately the information on the electron and the “active” neutrino components of the solar neutrino flux. In detail, we include the following experimental information, depicted in Fig. 1:

-

•

for keV, as extracted from a combined fit to Borexino and low-energy neutrino data Bellini:2011rx . This analysis is performed, effectively, by using Borexino data in order to establish the oscillated 7Be neutrino flux and hence extract the neutrino flux from other data. This procedure depends only weakly on the hypothesis that . This result is consistent with Borexino’s recent independent measurement of the low energy solar neutrino flux Bellini:2014uqa .

-

•

for keV from the Borexino data Bellini:2011rx . is the ratio of the to the elastic scattering cross-sections at 7Be neutrino energies.

-

•

SNO performed a detailed measurement of as a function of energy Aharmim:2011vm . We choose values at and , and , respectively, as representatives of the SNO data. These points are chosen in order to both capture the statistical power of the SNO experiment and to include some of the shape information. A proper treatment of the SNO data, including all different observables, correlations, etc., can only be handled by the Collaboration itself. We verify that, in the case , our extracted best fit value for and the associated one sigma error bar are in good agreement with the most recent global analyses of neutrino data Gonzalez-Garcia:2014bfa .

-

•

The SNO experiment is also sensitive to the presence of a flux from the Sun thanks to its neutral current and elastic scattering measurements. It is, therefore, possible to measure and as a function of energy with SNO data (see, for example, Ahmad:2002jz ). Ref. Aharmim:2011vm , however, does not discuss the independent extraction of from the data, replacing it instead by . Here we estimate the extracted value of from SNO data as follows. We define the central value using while fixing the one-sigma error bar on as that on , multiplied by . The factor of is very close to the ratio of the elastic cross-section to that for at 8B neutrino energies and agrees with the relative uncertainties for the electron and active neutrino fluxes measured by SNO in Ahmad:2002jz .

We note that SuperKamiokande also measures the neutrino flux using elastic neutrino–electron scattering (see, e.g., Abe:2010hy ). We do not include data from SuperKamiokande in our simplified fit as they mostly contributes to the measurement of – which we can only estimate here – and have a higher energy threshold than SNO data.

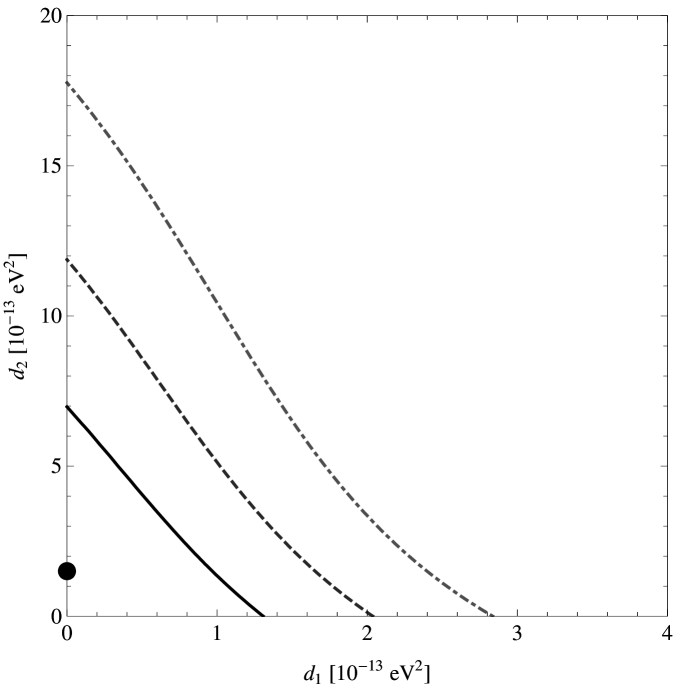

Fig. 2 depicts the result of our fit in the -plane, obtained after marginalizing over . The best fit point is eV2 and the hypothesis fits the data quite well. At the two-sigma confidence level, eV2 and eV2, in agreement with the naive estimates discussed above. The constraints above justify the approximations that led to Eq. (2), especially for all solar neutrino energies. Our result indicates that the neutrino decay hypothesis does not allow for a fit to the solar data that is significantly better than the standard “large mixing angle solution,” mostly due to the low energy 7Be and neutrino measurements. We emphasize, however, that a detailed analysis of all solar neutrino data including the neutrino decay hypothesis is best left to the experimental collaborations, and that a reanalysis of the SNO data – one that treats both and as independent functions – as a function of energy is required. We hope our results encourage the pursuit of such an analysis.

In summary, we have argued that the solar neutrino data, combined with reactor data, allow one to place mostly model-independent bounds on the lifetimes of and . Using a subset of the solar neutrino data and the data from KamLAND, we estimate that eV2 and eV2 at the two-sigma confidence level. A complete analysis would reveal exactly where these bounds lie. As a “by-product” of our analysis, the atmospheric neutrino bound discussed in GonzalezGarcia:2008ru applies, robustly, to : eV2. Along with solar and atmospheric neutrino data, the only other robust bound comes from SN1987A which translates, as discussed earlier, into for one of the three mass-eigenstates, most likely or .

The bounds are ‘mostly model-independent’ in the following sense. They are independent from the values of the neutrino masses themselves, and apply for both mass hierarchies. No assumption is made regarding the nature of the neutrino – Majorana or Dirac – or of the daughter particles into which the neutrinos would be decaying. We are assuming, however, that if the decay-daughters were to consist of lighter active neutrinos, these would not leave a significant imprint in the detectors under consideration, i.e., they don’t “look” like the parent neutrinos. This is a modest assumption. Daughter neutrinos from neutrino decay have, necessarily, less energy than their parents, and only those that decay along the flight-path of the parent make it to the detector. We also do not allow for the possibility, recently discussed in a more generic context Berryman:2014yoa , that the neutrino decay hypothesis translates into more mixing parameters, i.e., that the neutrino mass and decay eigenstates are not the same.

Acknowledgements

We thank Roberto Oliveira for useful discussions and collaboration during the early stages of this work. DH and AdG thank the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics in Santa Barbara, where part of this work was completed, for its hospitality. DH benefitted from fruitful discussions with Hisakazu Minakata, Sandip Pakvasa, Tom Weiler, and Walter Winter. The work of AdG and DH was supported in part by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. NSF PHY11-25915. This work is sponsored in part by the DOE grant #DE-FG02-91ER40684.

References

- (1) K.A. Olive et al. [Particle Data Group Collaboration], Chin. Phys. C 38, 090001 (2014).

- (2) C. Broggini, C. Giunti and A. Studenikin, Adv. High Energy Phys. 2012, 459526 (2012) [arXiv:1207.3980 [hep-ph]].

- (3) J.F. Beacom, N.F. Bell and S. Dodelson, Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 121302 (2004) [astro-ph/0404585].

- (4) S. Hannestad and G. Raffelt, Phys. Rev. D 72, 103514 (2005) [hep-ph/0509278].

- (5) P.D. Serpico, Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 171301 (2007) [astro-ph/0701699].

- (6) M.C. Gonzalez-Garcia and M. Maltoni, Phys. Lett. B 663, 405 (2008) [arXiv:0802.3699 [hep-ph]].

- (7) R.A. Gomes, A.L.G. Gomes and O.L.G. Peres, arXiv:1407.5640 [hep-ph].

- (8) J.A. Frieman, H.E. Haber and K. Freese, Phys. Lett. B 200, 115 (1988).

- (9) J.F. Beacom, N.F. Bell, D. Hooper, S. Pakvasa and T.J. Weiler, Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 181301 (2003) [hep-ph/0211305].

- (10) D. Meloni and T. Ohlsson, Phys. Rev. D 75, 125017 (2007) [hep-ph/0612279].

- (11) P. Baerwald, M. Bustamante and W. Winter, JCAP 1210, 020 (2012) [arXiv:1208.4600 [astro-ph.CO]].

- (12) S. Pakvasa, A. Joshipura and S. Mohanty, Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 171802 (2013) [arXiv:1209.5630 [hep-ph]].

- (13) L. Dorame, O.G. Miranda and J.W.F. Valle, arXiv:1303.4891 [hep-ph].

- (14) L. Fu and C.M. Ho, arXiv:1407.1090 [hep-ph].

- (15) M.G. Aartsen et al. [IceCube Collaboration], Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 021103 (2013) [arXiv:1304.5356 [astro-ph.HE]].

- (16) J.F. Beacom and N.F. Bell, Phys. Rev. D 65, 113009 (2002) [hep-ph/0204111].

- (17) A. Gando et al. [KamLAND Collaboration], Phys. Rev. D 83, 052002 (2011) [arXiv:1009.4771 [hep-ex]].

- (18) G. Bellini, J. Benziger, D. Bick, S. Bonetti, G. Bonfini, M. Buizza Avanzini, B. Caccianiga and L. Cadonati et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 141302 (2011) [arXiv:1104.1816 [hep-ex]].

- (19) F.P. An et al. [Daya Bay Collaboration], Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 061801 (2014) [arXiv:1310.6732 [hep-ex]].

- (20) J.K. Ahn et al. [RENO Collaboration], Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 191802 (2012) [arXiv:1204.0626 [hep-ex]].

- (21) Y. Abe et al. [Double Chooz Collaboration], Phys. Rev. D 86, 052008 (2012) [arXiv:1207.6632 [hep-ex]].

- (22) K. Abe et al. [T2K Collaboration], Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 061802 (2014) [arXiv:1311.4750 [hep-ex]].

- (23) B. Aharmim et al. [SNO Collaboration], Phys. Rev. C 88, 025501 (2013) [arXiv:1109.0763 [nucl-ex]].

- (24) A. de Gouvêa, A. Friedland and H. Murayama, Phys. Lett. B 490, 125 (2000) [hep-ph/0002064].

- (25) G. Bellini et al. [BOREXINO Collaboration], Nature 512, no. 7515, 383 (2014).

- (26) M.C. Gonzalez-Garcia, M. Maltoni and T. Schwetz, arXiv:1409.5439 [hep-ph].

- (27) K. Abe et al. [Super-Kamiokande Collaboration], Phys. Rev. D 83, 052010 (2011) [arXiv:1010.0118 [hep-ex]].

- (28) Q.R. Ahmad et al. [SNO Collaboration], Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 011301 (2002) [nucl-ex/0204008].

- (29) J.M. Berryman, A. de Gouvêa, D. Hernández and R.L.N. Oliviera, arXiv:1407.6631 [hep-ph].