Sparse random graphs: Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors

Abstract

In this paper we prove the semi-circular law for the eigenvalues of regular random graph in the case , complementing a previous result of McKay for fixed . We also obtain a upper bound on the infinity norm of eigenvectors of Erdős-Rényi random graph , answering a question raised by Dekel-Lee-Linial.

1 Introduction

1.1 Overview

In this paper, we consider two models of random graphs, the Erdős-Rényi random graph and the random regular graph . Given a real number ,, the Erdős-Rényi graph on a vertex set of size is obtained by drawing an edge between each pair of vertices, randomly and independently, with probability . On the other hand, , where denotes the degree, is a random graph chosen uniformly from the set of all simple -regular graphs on vertices. These are basic models in the theory of random graphs. For further information, we refer the readers to the excellent monographs and survey [33].

Given a graph on vertices, the adjacency matrix of is an matrix whose entry equals one if there is an edge between the vertices and and zero otherwise. All diagonal entries are defined to be zero. The eigenvalues and eigenvectors of carry valuable information about the structure of the graph and have been studied by many researchers for quite some time, with both theoretical and practical motivations (see, for example, , , ).

The goal of this paper is to study the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of and . We are going to consider:

-

•

The global law for the limit of the empirical spectral distribution (ESD) of adjacency matrices of and . For , it is well-known that eigenvalues of (after a proper scaling) follows Wigner’s semicircle law (we include a short proof in the Appendix A for completeness). Our main new result shows that the same law holds for random regular graph with with . This complements the well known result of McKay for the case when is an absolute constant (McKay’s law) and extends recent results of Dumitriu and Pal [9] (see Section 1.2 for more discussion).

-

•

Bound on the infinity norm of the eigenvectors. We first prove that the infinity norm of any (unit) eigenvector of is almost surely for . This gives a positive answer to a question raised by Dekel, Lee and Linial [7]. Furthermore, we can show that satisfies the bound for , as long as the corresponding eigenvalue is bounded away from the (normalized) extremal values and .

We finish this section with some notation and conventions.

Given an symmetric matrix , we denote its eigenvalues as

and let be an orthonormal basis of eigenvectors of with

The empirical spectral distribution (ESD) of the matrix is a one-dimensional function

where we use to denote the cardinality of a set .

Let be the adjacency matrix of . Thus is a random symmetric matrix whose upper triangular entries are iid copies of a real random variable and diagonal entries are . is a Bernoulli random variable that takes values with probability and with probability .

Usually it is more convenient to study the normalized matrix

where is the matrix all of whose entries are 1. has entries with mean zero and variance one. The global properties of the eigenvalues of and are essentially the same (after proper scaling), thanks to the following lemma

Lemma 1.1.

(Lemma 36, [30]) Let be symmetric matrices of the same size where has rank one. Then for any interval ,

where is the number of eigenvalues of in .

Definition 1.2.

Let be an event depending on . Then holds with overwhelming probability if .

The main advantage of this definition is that if we have a polynomial number of events, each of which holds with overwhelming probability, then their intersection also holds with overwhelming probability.

Asymptotic notation is used under the assumption that . For functions and of parameter , we use the following notation as : if is bounded from above; if ; if , or equivalently, ; if ; if and .

1.2 The semicircle law

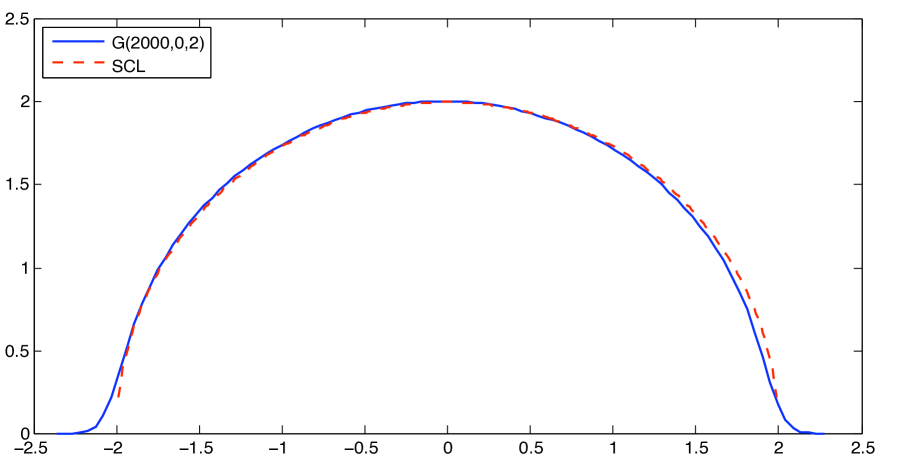

In 1950s, Wigner [32] discovered the famous semi-circle for the limiting distribution of the eigenvalues of random matrices. His proof extends, without difficulty, to the adjacency matrix of , given that with . (See Figure 1 for a numerical simulation)

Theorem 1.3.

For , the empirical spectral distribution (ESD) of the matrix converges in distribution to the semicircle distribution which has a density with support on ,

\captionstyle

\captionstyle

center \onelinecaptionsfalse

If , the semicircle law no longer holds. In this case, the graph almost surely has isolated vertices, so in the limiting distribution, the point will have positive constant mass.

The case of random regular graph, , was considered by McKay [21] about 30 years ago. He proved that if is fixed, and , then the limiting density function is

This is usually referred to as McKay or Kesten-McKay law.

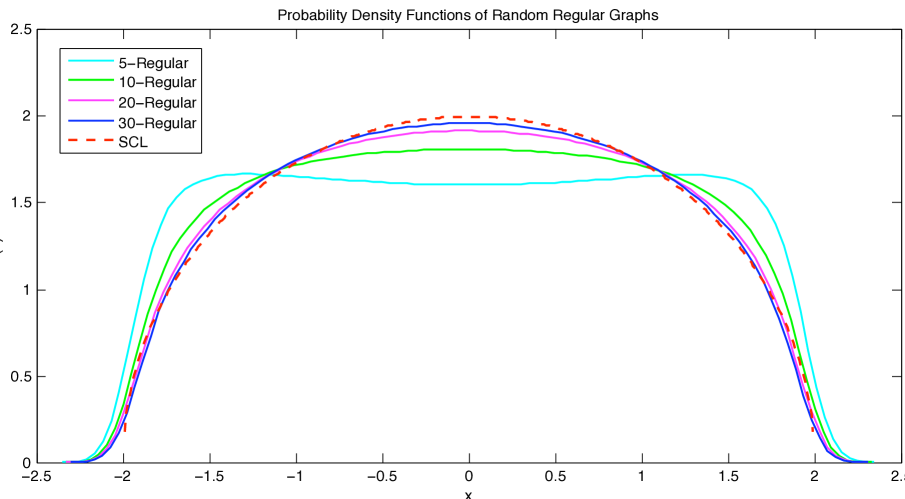

It is easy to verify that as , if we normalize the variable by , then the above density converges to the semicircle distribution on . In fact, a numerical simulation shows the convergence is quite fast(see Figure 2).

\captionstyle

\captionstyle

center \onelinecaptionsfalse

Random -regular graphs with 1000 vertices

It is thus natural to conjecture that Theorem 1.3 holds for with . Let be the adjacency matrix of , and set

Conjecture 1.4.

If then the ESD of converges to the standard semicircle distribution.

Nothing has been proved about this conjecture, until recently. In [9], Dimitriu and Pal showed that the conjecture holds for tending to infinity slowly, . Their method does not extend to larger .

We are going to establish Conjecture 1.4 in full generality. Our method is very different from that of [9].

Without loss of generality we may assume , since the adjacency matrix of the complement graph of may be written as , thus by Lemma 1.1 will have the spectrum interlacing between the set . Since the semi-circular distribution is symmetric, the ESD of will converges to semi-circular law if and only if the ESD of its complement does.

Theorem 1.5.

If tends to infinity with , then the empirical spectral distribution of converges in distribution to the semicircle distribution.

Theorem 1.5 is a direct consequence of the following stronger result, which shows convergence at small scales. For an interval let be the number of eigenvalues of in .

Theorem 1.6.

(Concentration for ESD of ). Let and consider the model . If tends to as then for any interval with length at least , we have

with probability at least .

1.3 Infinity norm of the eigenvectors

Relatively little is known for eigenvectors in both random graph models under study. In [7], Dekel, Lee and Linial, motivated by the study of nodal domains, raised the following question.

Question 1.8.

Is it true that almost surely every eigenvector of has ?

Later, in their journal paper [8], the authors added one sharper question.

Question 1.9.

Is it true that almost surely every eigenvector of has ?

The bound was also conjectured by the second author of this paper in an NSF proposal (submitted Oct 2008). He and Tao [30] proved this bound for eigenvectors corresponding to the eigenvalues in the bulk of the spectrum for the case . If one defines the adjacency matrix by writting for non-edges, then this bound holds for all eigenvectors [30, 29].

The above two questions were raised under the assumption that is a constant in the interval . For depending on , the statements may fail. If , then the graph has (with high probability) isolated vertices and so one cannot expect that for every eigenvector . We raise the following questions:

Question 1.10.

Assume for some constant . Is it true that almost surely every eigenvector of has ?

Question 1.11.

Assume for some constant . Is it true that almost surely every eigenvector of has ?

Similarly, we can ask the above questions for :

Question 1.12.

Assume for some constant . Is it true that almost surely every eigenvector of has ?

Question 1.13.

Assume for some constant . Is it true that almost surely every eigenvector of has ?

As far as random regular graphs is concerned, Dumitriu and Pal [9] and Brook and Lindenstrauss [5] showed that for any normalized eigenvector of a sparse random regular graph is delocalized in the sense that one can not have too much mass on a small set of coordinates. The readers may want to consult their papers for explicit statements.

We generalize our questions by the following conjectures:

Conjecture 1.14.

Assume for some constant . Let be a random unit vector whose distribution is uniform in the -dimensional unit sphere. Let be a unit eigenvector of and be any fixed -dimensional vector. Then for any

Conjecture 1.15.

Assume for some constant . Let be a random unit vector whose distribution is uniform in the -dimensional unit sphere. Let be a unit eigenvector of and be any fixed -dimensional vector. Then for any

In this paper, we focus on . Our main result settles (positively) Question 1.8 and almost Question 1.10 . This result follows from Corollary 2.3 obtained in Section 2.

Theorem 1.16.

(Infinity norm of eigenvectors) Let and let be the adjacency matrix of . Then there exists an orthonormal basis of eigenvectors of , , such that for every , almost surely.

For Questions 1.9 and 1.11, we obtain a good quantitative bound for those eigenvectors which correspond to eigenvalues bounded away from the edge of the spectrum.

For convenience, in the case when , we write

where is a positive function such that as ( can tend to arbitrarily slowly).

Theorem 1.17.

Assume , where is defined as above. Let . For any , and any with , there exists a corresponding eigenvector such that with overwhelming probability.

2 Semicircle law for regular random graphs

2.1 Proof of Theorem 1.6

We use the method of comparison. An important lemma is the following

Lemma 2.1.

If then is -regular with probability at least .

For the range , Lemma 2.1 is a consequence of a result of Shamir and Upfal [26] (see also [20]). For smaller values of , McKay and Wormald [23] calculated precisely the probability that is -regular, using the fact that the joint distribution of the degree sequence of can be approximated by a simple model derived from independent random variables with binomial distribution. Alternatively, one may calculate the same probability directly using the asymptotic formula for the number of -regular graphs on vertices (again by McKay and Wormald [22]). Either way, for , we know that

which is better than claimed in Lemma 2.1.

Another key ingredient is the following concentration lemma, which may be of independent interest.

Lemma 2.2.

Let be a Hermitian random matrix whose off-diagonal entries are i.i.d. random variables with mean zero, variance 1 and for some common constant . Fix and assume that the forth moment . Then for any interval whose length is at least , the number of the eigenvalues of which belong to satisfies the following concentration inequality

Apply Lemma 2.2 for the normalized adjacency matrix of with we obtain

Corollary 2.3.

Consider the model with as and let . Then for any interval with length at least , we have

with probability at most .

Remark 2.4.

If one only needs the result for the bulk case for an absolute constant then the minimum length of can be improved to .

By Corollary 2.3 and Lemma 2.1, the probability that fails to be close to the expected value in the model is much smaller than the probability that is -regular. Thus the probability that fails to be close to the expected value in the model where is the ratio of the two former probabilities, which is for some small positive constant . Thus, Theorem 1.6 is proved, depending on Lemma 2.2 which we turn to next.

2.2 Proof of Lemma 2.2

Assume and .

We will use the approach of Guionnet and Zeitouni in [18]. Consider a random Hermitian matrix with independent entries with support in a compact region . Let be a real convex -Lipschitz function and define

where ’s are the eigenvalues of . We are going to view as the function of the atom variables . For our application we need to be random variables with mean zero and variance 1, whose absolute values are bounded by a common constant .

The following concentration inequality is from [18]

Lemma 2.5.

Let be as above. Then there is a constant such that for any

In order to apply Lemma 2.5 for and , it is natural to consider

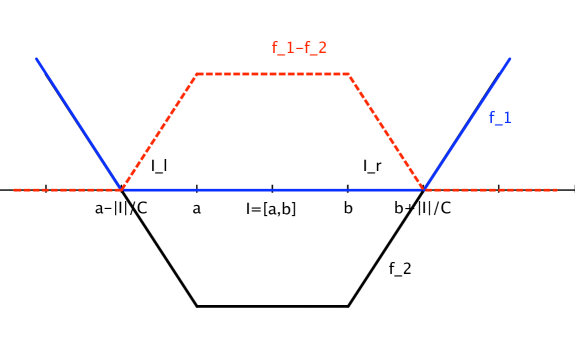

where is the indicator function of and are the eigenvalues of . However, this function is neither convex nor Lipschitz. As suggested in [18], one can overcome this problem by a proper approximation. Define , and construct two real functions as follows(see Figure 3):

where is a constant to be chosen later. Note that ’s are convex and -Lipschitz. Define

and apply Lemma 2.5 with for and . Thus, we have

At this point we need to estimate the value of . There are two cases: if is in the “bulk” i.e. for some positive absolute constant , then where is a constant depending on . But if is very near the edge of i.e. , then for some absolute constant . Thus in both case we have

Let , then

Now we compare to , making use of a result of Götze and Tikhomirov [17]. We have . In [17], Götze and Tikhomirov obtained a convergence rate for ESD of Hermitian random matrices whose entries have mean zero and variance one, which implies that for any

where is an absolute constant, . Thus

In the “edge” case we can choose , then because , we have

and

In the “bulk” case we choose , then

Therefore in both cases, with probability at least , we have

The convergence rate result of Götze and Tikhomirov again gives

hence with probability at least

which is the desires upper bound.

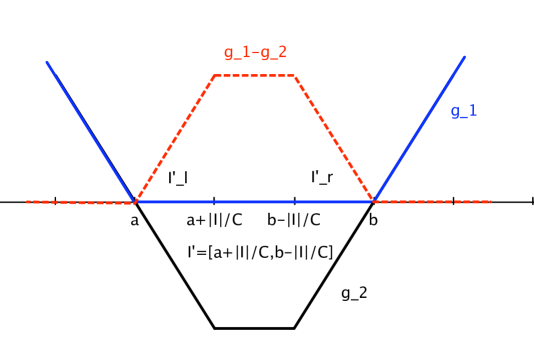

The lower bound is proved using a similar argument. Let , , where is to be chosen later and define two functions , as follows (see Figure 3):

We have . A similar argument as in the proof of the upper bound (using the convergence rate of Götze and Tikhomirov) shows

Therefore with probability at least , we have

and by the convergence rate, with probability at least

Thus, Theorem 2.2 is proved.

3 Infinity norm of the eigenvectors

3.1 Small perturbation lemma

is the adjacency matrix of . In the proofs of Theorem 1.16 and Theorem 1.17, we actually work with the eigenvectors of a perturbed matrix

where can be arbitrarily small and is a symmetric random matrix whose upper triangular elements are independent with a standard Gaussian distribution.

The entries of are continuous and thus with probability 1, the eigenvalues of are simple. Let

be the ordered eigenvalues of , which have a unique orthonormal system of eigenvectors . By the Cauchy interlacing principle, the eigenvalues of are different from those of its principle minors, which satisfies a condition of Lemma 3.2.

Let ’s be the eigenvalue of with multiplicity defined as follows:

By Weyl’s theorem, one has for every ,

| (3.1) |

Thus the behaviors of eigenvalues of and are essentially the same by choosing sufficiently small. And everything (except Lemma 3.2) we used in the proofs of Theorem 1.16 and Theorem 1.17 for also applies for by a continuity argument. We will not distinguish from in the proofs.

The following lemma will allow us to transfer the eigenvector delocaliztion results of to those of at some expense.

Lemma 3.1.

In the notations of above, there exists an orthonormal basis of eigenvectors of , denoted by , such that for every ,

where can be arbitrarily small provided is small enough.

Proof.

First, since the coefficients of the characteristic polynomial of are integers, there exists a positive function such that either or for any .

By (3.1) and choosing sufficiently small, one can get

For a fixed index , let be the eigenspace corresponding to the eigenvalue and be the subspace spanned by . Both of and have dimension . Let and be the orthogonal projection matrices onto and separately.

Applying the well-known Davis-Kahan theorem (see [28] Section IV, Theorem 3.6) to and , one gets

where can be arbitrarily small depending on

Define for , then we have . It is clear that are eigenvectors of and

By choosing small enough such that , are linearly independent. Indeed, if , one has for every , , which implies . Thus summing over all , we can get and therefore .

Furthermore the set is ’almost’ an orthonormal basis of in the sense that

We can perform a Gram-Schmidt process on to get an orthonormal system of eigenvectors on such that

for every .

We iterate the above argument for every distinct eigenvalue of to obtain an orthonormal basis of eigenvectors of .

∎

3.2 Auxiliary lemmas

Lemma 3.2.

(Lemma 41, [30]) Let

be a symmetric matrix for some and , and let be a eigenvector of with eigenvalue , where and . Suppose that none of the eigenvalues of are equal to . Then

where is a unit eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalue

The Stieltjes transform of a symmetric matrix is defined for by the formula

It has the following alternate representation:

Lemma 3.3.

(Lemma 39, [30]) Let be a symmetrix matrix, and let be a complex number not in the spectrum of . Then we have

where is the matrix with the row and column of removed, and is the column of with the entry removed.

We begin with two lemmas that will be needed to prove the main results. The first lemma, following the paper [30] in Appendix B, uses Talagrand’s inequality. Its proof is presented in the Appendix B.

Lemma 3.4.

Let be a random vector whose entries are i.i.d. copies of the random variable (with mean and variance ). Let be a subspace of dimension and the orthogonal projection onto H. Then

In particular,

| (3.2) |

with overwhelming probability.

The following concentration lemma for will be a key input to prove Theorem 1.17. Let

Lemma 3.5 (Concentration for ESD in the bulk).

(Concentration for ESD in the bulk) Assume . For any constants and any interval in of width , the number of eigenvalues of in obeys the concentration estimate

with overwhelming probability.

3.3 Proof of Theorem 1.16:

Let be the largest eigenvalue of and be the corresponding unit eigenvector. We have the lower bound . And if , then the maximum degree almost surely (See Corollary 3.14, [4]).

For every ,

where is the neighborhood of vertex . Thus, by Cauchy-Schwarz inequality,

Let . Since the eigenvalues of are on the interval , by Lemma 1.1, .

Recall that . By Corollary 2.3, for any interval with length at least (say ),with overwhelming probability, if for some positive constant , one has ; if is at the edge of , with length , one has . Thus we can find a set with ) or such that for all , where is the bottom right minor of . Here we take . It is easy to check that .

By the formula in Lemma 3.2, the entry of the eigenvector of can be expressed as

| (3.3) |

with overwhelming probability, where is the span of all the eigenvectors associated to with dimension , is the orthogonal projection onto and has entries that are iid copies of . The last inequality in (3.3) follows from Lemma 3.4 (by taking ) and the relations

Here and , where is the space orthogonal to the all 1 vector . For the dimension of , .

Since either ) or , we have ) or ). Thus or . In both cases, since , it follows that .

3.4 Proof of Theorem 1.17

With the formula in Lemma 3.2, it suffices to show the following lower bound

| (3.4) |

with overwhelming probability, where is the bottom right minor of and has entries that are iid copies of . Recall that takes values with probability and with probability , thus .

By Theorem 3.5, we can find a set with such that for all . Thus in (3.4), it is enough to prove

or equivalently

| (3.5) |

with overwhelming probability, where is the span of all the eigenvectors associated to with dimension .

Let , where is the space orthogonal to . The dimension of is at least . Denote . Then the entries of are iid copies of . By Lemma 3.4,

with overwhelming probability.

Hence, our claim follows from the relations

Appendix A Proof of Theorem 1.3

We will show that the semicircle law holds for . With Lemma 1.1, it is clear that Theorem 1.3 follows Lemma A.1 directly. The claim actually follows as a special case discussed in the paper [6]. Our proof here uses a standard moment method.

Lemma A.1.

For , the empirical spectral distribution (ESD) of the matrix converges in distribution to the semicircle law which has a density with support on ,

Let be the entries of . For , ; and for , are iid copies of random variable , which takes value with probability and takes value with probability .

For a positive integer , the moment of ESD of the matrix is

and the moment of the semicircle distribution is

On a compact set, convergence in distribution is the same as convergence of moments. To prove the theorem, we need to show, for every fixed number ,

| (A.1) |

For , by symmetry, .

For ,

Thus our claim (A.1) follows by showing that

| (A.2) |

We have the expansion for the trace of ,

| (A.3) |

Each term in the above sum corresponds to a closed walk of length on the complete graph on . On the other hand, are independent with mean 0. Thus the term is nonzero if and only if every edge in this closed walk appears at least twice. And we call such a walk a good walk. Consider a good walk that uses different edges with corresponding multiplicities , where , each and . Now the corresponding term to this good walk has form

Since such a walk uses at most vertices, a naive upper bound for the number of good walks of this type is .

When , recall , and so

When , we classify the good walks into two types. The first kind uses different edges. The contribution of these terms will be

The second kind of good walk uses exactly different edges and thus different vertices. And the corresponding term for each walk has form

The number of this kind of good walk is given by the following result in the paper ([1], Page 617–618):

Lemma A.2.

The number of the second kind of good walk is

Then the second conclusion of (A.1) follows.

Appendix B Proof of Lemma 3.4:

The coordinates of are bounded in magnitude by . Apply Talagrand’s inequality to the map , which is convex and -Lipschitz. We can conclude

| (B.1) |

where is the median of .

Let be the orthogonal projection matrix onto . One has tracetrace and , as well as,

and

Take . To complete the proof, it suffices to show

| (B.2) |

Consider the event that , which implies that

Let and .

Now we have

By Chebyshev’s inequality,

where .

Therefore,

On the other hand, we have and

It follows that and hence

For the lower bound, consider the event that and notice that

Appendix C Proof of Lemma 3.5:

Recall the normalized adjacency matrix

where is the matrix of all ’s, and let .

Lemma C.1.

For all intervals with , one has

with overwhelming probability.

Actually we will prove the following concentration theorem for . By Lemma 1.1, , therefore Lemma C.2 implies Lemma 3.5.

Lemma C.2.

(Concentration for ESD in the bulk) Assume . For any constants and any interval in of width , the number of eigenvalues of in obeys the concentration estimate

with overwhelming probability.

To prove Theorem C.2, following the proof in [30], we consider the Stieltjes transform

whose imaginary part

in the upper half-plane .

The semicircle counterpart

is the unique solution to the equation

with .

The next proposition gives control of ESD through control of Stieltjes transform (we will take in the proof):

Proposition C.3.

(Lemma 60, [30]) Let . Suppose that one has the bound

with (uniformly) overwhelming probability for all with and . Then for any interval in with , one has

with overwhelming probability.

By Proposition C.3, our objective is to show

| (C.1) |

with (uniformly) overwhelming probability for all with and , where

In Lemma 3.3, we write

| (C.2) |

where

is the matrix with the row and column removed, and is the row of with the element removed.

The entries of are independent of each other and of , and have mean zero and variance . By linearity of expectation we have

where

is the Stieltjes transform of . From the Cauchy interlacing law, we get

and thus

In fact a similar estimate holds for itself:

Proposition C.4.

For , holds with (uniformly) overwhelming probability for all with and .

Assume this proposition for the moment. By hypothesis, . Thus in (C.2), we actually get

| (C.3) |

with overwhelming probability. This implies that with overwhelming probability either or that . On the other hand, as Im is necessarily positive, the second possibility can only occur when Im. A continuity argument (as in [11]) then shows that the second possibility cannot occur at all and the claim follows.

Now it remains to prove Proposition C.4.

Proof of Proposition C.4. Decompose

and evaluate

| (C.4) |

where we denote , are orthonormal eigenvectors of .

Let , then

where is the space spanned by for and is the orthogonal projection onto .

In Lemma 3.4, by taking , where , one can conclude with overwhelming probability

| (C.5) |

Using the triangle inequality,

| (C.6) |

with overwhelming probability.

Let , where and , define two parameters

First, for those such that , the function has magnitude . From Lemma C.1, , and so the contribution for these is,

For the contribution of the remaining , we subdivide the indices as

where , for , and then sum over .

For each such interval, the function has magnitude and fluctuates by at most . Say is the set of all ’s in this interval, thus by Lemma C.1, . Together with bounds (C.5), (C.6), the contribution for these on such an interval,

Summing over and noticing that , we get

Acknowledgement. The authors thank Terence Tao for useful conversations.

References

- [1] Z.D. Bai. Methodologies in spectral analysis of large dimensional random matrices, a review. In Advances in statistics: proceedings of the conference in honor of Professor Zhidong Bai on his 65th birthday, National University of Singapore, 20 July 2008, volume 9, page 174. World Scientific Pub Co Inc, 2008.

- [2] M. Bauer and O. Golinelli. Random incidence matrices: moments of the spectral density. Journal of Statistical Physics, 103(1):301–337, 2001.

- [3] S. Bhamidi, S.N. Evans, and A. Sen. Spectra of large random trees. Arxiv preprint arXiv:0903.3589, 2009.

- [4] B. Bollobás. Random graphs. Cambridge Univ Pr, 2001.

- [5] S. Brooks and E. Lindenstrauss. Non-localization of eigenfunctions on large regular graphs. Arxiv preprint arXiv:0912.3239, 2009.

- [6] F. Chung, L. Lu, and V. Vu. The spectra of random graphs with given expected degrees. Internet Mathematics, 1(3):257–275, 2004.

- [7] Y. Dekel, J. Lee, and N. Linial. Eigenvectors of random graphs: Nodal domains. In APPROX ’07/RANDOM ’07: Proceedings of the 10th International Workshop on Approximation and the 11th International Workshop on Randomization, and Combinatorial Optimization. Algorithms and Techniques, pages 436–448, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007. Springer-Verlag.

- [8] Y. Dekel, J. Lee, and N. Linial. Eigenvectors of random graphs: Nodal domains. Approximation, Randomization, and Combinatorial Optimization. Algorithms and Techniques, pages 436–448, 2008.

- [9] I. Dumitriu and S. Pal. Sparse regular random graphs: spectral density and eigenvectors. Arxiv preprint arXiv:0910.5306, 2009.

- [10] L. Erdos, B. Schlein, and H.T. Yau. Semicircle law on short scales and delocalization of eigenvectors for Wigner random matrices. Ann. Probab, 37(3):815–852, 2009.

- [11] L. Erdos, B. Schlein, and H.T. Yau. Local semicircle law and complete delocalization for Wigner random matrices. Accepted in Comm. Math. Phys. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 287(2):641–655, 2010.

- [12] U. Feige and E. Ofek. Spectral techniques applied to sparse random graphs. Random Structures and Algorithms, 27(2):251, 2005.

- [13] J. Friedman. On the second eigenvalue and random walks in random -regular graphs. Combinatorica, 11(4):331–362, 1991.

- [14] J. Friedman. Some geometric aspects of graphs and their eigenfunctions. Duke Math. J, 69(3):487–525, 1993.

- [15] J. Friedman. A proof of Alon’s second eigenvalue conjecture. In Proceedings of the thirty-fifth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing, pages 720–724. ACM, 2003.

- [16] Z Füredi and J. Komlós. The eigenvalues of random symmetric matrices. Combinatorica, 1(3):233–241, 1981.

- [17] F. Götze and A. Tikhomirov. Rate of convergence to the semi-circular law. Probability Theory and Related Fields, 127(2):228–276, 2003.

- [18] A. Guionnet and O. Zeitouni. Concentration of the spectral measure for large matrices. Electron. Comm. Probab, 5:119–136, 2000.

- [19] S. Janson, T. Łuczak, and A. Ruciński. Random graphs. Citeseer, 2000.

- [20] M. Krivelevich, B. Sudakov, V.H. Vu, and N.C. Wormald. Random regular graphs of high degree. Random Structures and Algorithms, 18(4):346–363, 2001.

- [21] B.D. McKay. The expected eigenvalue distribution of a large regular graph. Linear Algebra and its Applications, 40:203–216, 1981.

- [22] B.D. McKay and N.C. Wormald. Asymptotic enumeration by degree sequence of graphs with degrees . Combinatorica 11 , no. 4, 369–382., 1991.

- [23] B.D. McKay and N.C. Wormald. The degree sequence of a random graph. I. The models. Random Structures Algorithms 11, no. 2, 97–117, 1997.

- [24] A. Pothen, H.D. Simon, and K.P. Liou. Partitioning sparse matrices with eigenvectors of graphs. SIAM Journal on Matrix Analysis and Applications, 11:430, 1990.

- [25] G. Semerjian and L.F. Cugliandolo. Sparse random matrices: the eigenvalue spectrum revisited. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General, 35:4837–4851, 2002.

- [26] E Shamir and E Upfal. Large regular factors in random graphs. Convexity and graph theory (Jerusalem, 1981), 1981.

- [27] J. Shi and J. Malik. Normalized cuts and image segmentation. IEEE Transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, 22(8):888–905, 2000.

- [28] G.W. Stewart and Ji-guang. Sun. Matrix perturbation theory. Academic press New York, 1990.

- [29] T. Tao and V. Vu. Random matrices: Universality of local eigenvalue statistics up to the edge. Communications in Mathematical Physics, pages 1–24, 2010.

- [30] T. Tao and V. Vu. Random matrices: Universality of the local eigenvalue statistics, submitted. Institute of Mathematics, University of Munich, Theresienstr, 39, 2010.

- [31] V. Vu. Random discrete matrices. Horizons of Combinatorics, pages 257–280, 2008.

- [32] E.P. Wigner. On the distribution of the roots of certain symmetric matrices. Annals of Mathematics, 67(2):325–327, 1958.

- [33] N.C. Wormald. Models of random regular graphs. London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series, pages 239–298, 1999.