Spatial Distribution of Nucleosynthesis Products in Cassiopeia A: Comparison Between Observations and 3D Explosion Models

Abstract:

We examine observed heavy element abundances in the Cassiopeia A supernova remnant as a constraint on the nature of the Cas A supernova. We compare bulk abundances from 1D and 3D explosion models and spatial distribution of elements in 3D models with those derived from X-ray observations. We also examine the cospatial production of 26Al with other species. We find that the most reliable indicator of the presence of 26Al in unmixed ejecta is a very low S/Si ratio (). Production of N in O/S/Si-rich regions is also indicative. The biologically important element P is produced at its highest abundance in the same regions. Proxies should be detectable in supernova ejecta with high spatial resolution multiwavelength observations.

1 Introduction

Cassiopeia A is perhaps the best studied young Galactic supernova Remnant (SNR). It is nearby (3.4 kpc) [Reed et al. 1995] and young ( yr) [Thorstensen, Fesen, & van den Bergh 2001]. The wealth of data from ground-based observations in the optical, IR, and radio and from space in the optical, x-ray, and -ray allow us to study its morphology and composition in great detail. In [Young et al. 2006] we attempted to narrow down the possibilities for the progenitor star of Cas A using comparisons between computational models and different lines of observational evidence. We believe the most probable candidate for the progenitor of Cas A is a 15-25 star in an unequal mass binary. This will form the basic assumption of our analysis in this paper.

This work ties into the larger NuGrid collaboration. We will examine the sensitivity of our results to our choice of nuclear rates , determining the dominant rates affecting these yields and calculating the error in these yields caused by the uncertainty in the rates. We can then compare these errors to current errors in the hydrodynamics, using observed supernovae such as Cas A as verification tests in the manner discussed here.

2 Calculations

These calculations explore four different progenitor models each for a range of explosion scenarios. We use a large set of thermally driven 1D explosions with varying delays for a star of initial mass 23 and a more restricted range of explosions for a 16 and 23 with the hydrogen envelope stripped in a case B binary scenario and a 40 that ends its life as a type WC/O after extensive mass loss. We also examine a 3D explosion of the 23 binary progenitor.

2.1 1D Explosions

To model collapse and explosion, we use a 1-dimensional Lagrangian code developed by Herant et al. (1994). This code includes 3-flavor neutrino transport using a flux-limited diffusion calculation and a coupled set of equations of state to model the wide range of densities in the collapse phase [Herant et al. 1994, Fryer et al. 1999a]. It includes a 14-element nuclear network [Benz, Thielemann, & Hills 1989] to follow energy generation.

2.2 3D Explosions

Our 3-dimensional simulations use the output of the 1-D explosion (23 M⊙ star, 23m-run5) when the shock has reached 109 cm. We map the structure of this explosion into our 3D Smooth Particle Hydrodynamics code SNSPH [Fryer et al. 2006a]. To simulate an asymmetric explosion, we modify the velocities within each shell based on angular position. The velocities of particles within 30∘ of the z-axis were increased by a factor of 6 and the remaining particles were decreased by a factor of 1.2, roughly conserving the explosion energy. We will refer to these as high velocity structures (HVS). At these early times in the explosion, much of the energy remains in thermal energy, so the total asymmetry in the explosion is not as extreme as our velocity modifications suggest. The large velocity asymmetry results in roughly a factor of two spatial asymmetry between the axes. In this calculation, we model the explosion using 1 million SPH particles.

2.3 Nucleosynthesis Post-processing

Nucleosynthesis post-processing was performed with the Burn code [Young & Fryer 2007], using a 524 element network terminating at 99Tc. Reverse rates are calculated from detailed balance and allow a smooth transition to a nuclear statistical equilibrium (NSE) solver at K.

3 Explosion Geometry

At 800 seconds we cannot yet compare the simulation to the detailed observed abundances, but we can make statements about the gross morphology. We must account for two features. Most of the material is in a circular, flattened structure that is close to the plane of the sky. This is well-delineated by the fast moving optical knots, which are largely absent from the center of the remnant. In the x-ray, we see that higher atomic number species exist preferentially towards the center of the remnant [Willingale et al. 2002]. These features can be reproduced at least qualitatively with a bipolar explosion with the axis oriented close to our line of sight. When the HVS expand the bubbles ”rupture” after leaving the dense remnant, producing a flattened main remnant with nucleosynthesis products of higher A progressively closer to the symmetry axis.

4 26Al Production

[Ouelette et al. 2007] find that for uniformly expanding SN ejecta, the reverse shock caused by the initial interaction of ejecta and a protoplanetary disk develops into a bow shock that deflects most of the supernova material around the disk, with injection efficiencies of order of a percent. The average ejecta composition is therefore probably not the appropriate quantity to add to the disk when considering enrichment by 26Al . An ejecta knot with the typical characteristics of those in the Cassiopeia A SNR would have a mostly or completely unmixed composition, and could deliver pure 26Al -rich material to a disk. Dense optical and infrared knots have densities at least three orders of magnitude greater than uniformly expanding ejecta. A dense knot is also the most likely part of the ejecta to undergo dust condensation. [Ouelette et al. 2008] find that for dust particles with a diameter the injection efficiencies approach 100%. For generous assumptions of the mass of ejected metals, distance from a supernova, and covering factor of a protoplanetary disk we estimate that a disk is likely to encounter only of order one knot that contributes significantly to its mass. Since 26Al or its proxies are unlikely to be detectable in a stellar/planetary system, we will consider looking for suitable enriching material in supernova remnants.

4.1 Detectability of 26Al Proxies

Can actually detect the characteristic enhancement or ratios of nucleosynthetic products that can reliably indicate the presence of 26Al in supernova ejecta?

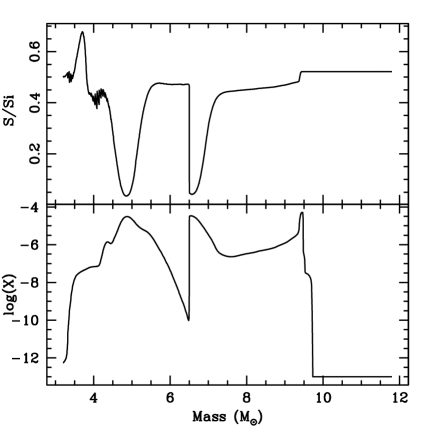

Si and S abundances turn out to be highly diagnostic (Figure 1) because of the production channel. The burning raises the Si abundance from log(X) to , primarily in 28Si . This is the typical abundance in the high 26Al regions. Temperatures are not high enough to produce significant amounts of S, so S/Si drops by a factor of about 10. Oxygen burning produces S efficiently at low entropies (16O (16O ,)32S ) and at high T transitioning to QSE, where S is thermodynamically favored over Si. As a result there is only a narrow range of mass in the star where S/Si drops much below 0.5. This coincides with the peak mass fraction of 26Al .

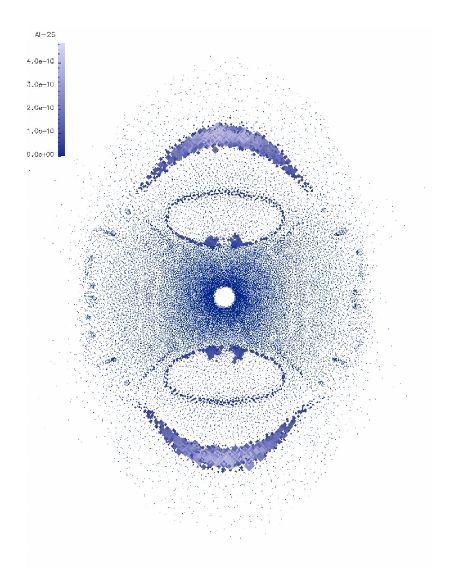

We find a similar pattern in the 3D explosion to the 1D results (Figure 2. In this case, in the spherically symmetric region no material is processed at high enough temperatures to produce 26Al . The HVS have a large region that consists of material that underwent carbon burning in the progenitor star at temperatures of K and reached peak shock temperatures of between 1 and 2K. This is the 26Al bubble. The ring consists of material that undergoes Ne burning in the progenitor (K) and explosive Ne and/or C burning (K). As in the 1D explosions, S/Si is very low and P production is high. The 3D explosion, with its more complicated thermodynamic history, reminds us that 1D does not tell the whole story. The yield is increased by higher temperatures and higher densities, but 26Al is rapidly destroyed by succeeding reactions. if there is a freezeout after the shock in which density drops rapidly, the high production can be achieved without subsequent destruction. This is the reason for the higher 26Al production in the sub-explosive C burning bubble than the explosive ring, the opposite of the pattern found in 1D. Large amounts of 18F are produced under the same conditions. If this excess flourine is not destroyed by subsequent burning it preferentially decays by 18F ()14N at temperatures above TK. Thus we have materialwith high levels of both N and O, Si, and S. These are potentially analogous to the Mixed Emission Knots (MEKs) identified by [Fesen 2001] in Cas A.

Detection of 26Al -rich material in core-collapse supernova remnants is a favorable situation. The characteristically low S/Si will be undiluted by mixing with ISM material in young remnants, so we should be able to predict which ejecta knots have high 26Al in well-resolved cases like Cas A. O-rich knots with high Mg or Na or moderately enhanced Si are good candidates for a combined optical/IR survey. The S/Si ratio of these knots would then provide a strong test of whether they would contain 26Al at high abundance. The Mixed Emission Knots in Cas A may also be excellent candidates. These knots are unique due to the simultaneous presence of significant emission from N and from O and S. The burning stages in a star that produce O and S destroy N very efficiently. It has therefore been assumed that these knots are most likely material from different locations in the progenitor star that are superimposed on line of sight or somehow mixed during the explosion. If these clumps are produced by a nucleosynthetic process they are most likely produced in the same conditions favorable for 26Al production.

References

- [Benz, Thielemann, & Hills 1989] Benz, W., Thielemann, F.-K., & Hills, J. G. 1989, ApJ, 342, 986

- [Fesen 2001] Fesen, Robert A. 2001, ApJS, 133, 161

- [Fryer et al. 1999a] Fryer, Chris, Benz, Willy, Herant, Marc, & Colgate, Stirling A. 1999, ApJ, 516, 892

- [Fryer et al. 2006a] Fryer, C.L., Rockefeller, G., & Warren, M.S. 2006, ApJ, 643, 292

- [Herant et al. 1994] Herant, Marc, Benz, Willy, Hix, W. Raphael, Fryer, Chris L., & Colgate, Stirling A. 1994, ApJ, 435, 339

- [Ouelette et al. 2007] Ouellette, N., Desch, S. J., & Hester, J. J. 2007, ApJ, 662, 1268

- [Ouelette et al. 2008] Ouellette, N., Desch, S. J., & Hester, J. J. 2008, Meteoritics and Planetary Science Supplement, 42, 5036

- [Reed et al. 1995] Reed, J. E., Hester, J. J., Fabian, A. C., & Winkler, P. F. 1995, ApJ, 440, 706

- [Thorstensen, Fesen, & van den Bergh 2001] Thorstensen, John R., Fesen, Robert A., & van den Bergh, Sidney 2001, AJ, 122, 297

- [Willingale et al. 2002] Willingale, R., Bleeker, J. A. M., van der Heyden, K. J., Kaastra, J. S., & Vink, J. 2002, A&A, 381, 1039

- [Young et al. 2006] Young, P.A., Fryer, C.L., Hungerford, A., Arnett, D., Rockefeller, G., Timmes, F.X., Voit, B., Meakin, C., Eriksen, K.A. 2006, ApJ, 640, 891

- [Young & Fryer 2007] Young, Patrick A. & Fryer, Chris L. 2007, ApJ, 664, 1033