Stationary measures of continuous time Markov chains with applications to stochastic reaction networks

Abstract.

We study continuous-time Markov chains on the non-negative integers under mild regularity conditions (in particular, the set of jump vectors is finite and both forward and backward jumps are possible). Based on the so-called flux balance equation, we derive an iterative formula for calculating stationary measures. Specifically, a stationary measure evaluated at is represented as a linear combination of a few generating terms, similarly to the characterization of a stationary measure of a birth-death process, where there is only one generating term, . The coefficients of the linear combination are recursively determined in terms of the transition rates of the Markov chain. For the class of Markov chains we consider, there is always at least one stationary measure (up to a scaling constant). We give various results pertaining to uniqueness and non-uniqueness of stationary measures, and show that the dimension of the linear space of signed invariant measures is at most the number of generating terms. A minimization problem is constructed in order to compute stationary measures numerically. Moreover, a heuristic linear approximation scheme is suggested for the same purpose by first approximating the generating terms. The correctness of the linear approximation scheme is justified in some special cases. Furthermore, a decomposition of the state space into different types of states (open and closed irreducible classes, and trapping, escaping and neutral states) is presented. Applications to stochastic reaction networks are well illustrated.

Key words and phrases:

Recurrence, explosivity, stationary distribution, signed invariant measure1. Introduction

Stochastic models of interacting particle systems are often formulated in terms of continuous-time Markov chains (CTMC) on a discrete state space. These models find application in population genetics, epidemiology and biochemistry, where the particles are known as species. A natural and accessible framework for representing interactions between species is a stochastic reaction network, where the underlying graph captures the possible jumps between states and the interactions between species. In the case where the reaction network consists of a single species, it is referred to as a one-species reaction network. Such networks frequently arise in various applications, ranging from SIS models in epidemiology [26] to bursty chemical processes (for example, in gene regulation) [27] and the Schlögl model [11]. One often focuses on examining the long-term dynamic behavior of the system, which can be captured by its corresponding limiting or stationary distribution, provided it exists. Therefore, characterizing the structure of such distributions is of great interest.

Stochastic models of reaction networks, in general, are highly non-linear, posing challenges for analytical approaches. Indeed, the characterization of stationary distributions remain largely incomplete [28], except for specific cases such as mono-molecular (linear) reaction networks [16], complex balanced reaction networks [2], and when the associated stochastic process is a birth-death process [4]. To obtain statistical information, it is common to resort to stochastic simulation algorithms [12, 9], running the Markov chain numerous times. However, this approach can be computationally intensive, rendering the analysis of complex reaction networks infeasible [21]. Furthermore, it fails to provide analytical insights into the system.

We investigate one-species reaction networks on the non-negative integers , and present an analytic characterization of stationary measures for general continuous-time Markov chains, subject to mild and natural regularity conditions (in particular, the set of jump vectors is finite and both forward and backwards jumps are possible), see Proposition 4.3. Furthermore, we provide a decomposition of the state space into different types of states: neutral, trapping, and escaping states, and positive and quasi-irreducible components (Proposition 3.1). Based on this characterization, we provide an iterative formula to calculate , , for any stationary measure , not limited to stationary distributions, in terms of a few generating terms (Theorem 4.4); similarly to the characterization of the stationary distribution/measure of a birth-death process with one generating term . The iterative formula is derived from the general flow balance equation [17].

Moreover, we show that the linear subspace of signed invariant measures has dimension at most the number of generating terms and that each signed invariant measure is given by the iterative formula and a vector of generating terms (Theorem 6.3). We use [15] to argue there always exists a stationary measure and give conditions for uniqueness and non-uniqueness (Corollary 5.5, Corollary 5.6, Theorem 6.6, Lemma 6.7). Furthermore, we demonstrate by example that there might be two or more linearly independent stationary measures (Example 9.5). As birth-death processes has a single generating term, then there cannot be a signed invariant measure taking values with both signs.

Finally, we demonstrate how the iterative formula can be used to approximate a stationary measure. Two methods are discussed: convex optimization (Theorem 7.1) and a heuristic linear approximation scheme (Lemma 7.2). We establish conditions under which the linear approximation scheme is correct, and provide simulation-based illustrations to support the findings. Furthermore, we observe that even when the aforementioned conditions are not met, the linear approximation scheme still produces satisfactory results. In particular, it allows us to recover stationary measures in certain cases. This approach offers an alternative to truncation approaches [14, 20] and forward-in-time simulation techniques such as Gillespie’s algorithm [12].

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Notation

Let , , be the non-negative real numbers, the positive real numbers, and the real numbers, respectively, the integers, the natural numbers and the non-negative integers. For , let denote the set of matrices over . The sign of is defined as if , if , and if . We use to denote the ceiling function, to denote the floor function, and to denote the -norm. Furthermore, let denote the indicator function of a set , where is the domain.

2.2. Markov Chains

We define a class of CTMCs on in terms of a finite set of jump vectors and non-negative transition functions. The setting can be extended to CTMCs on for and to infinite sets of jump vectors. Let be a finite set and a set of non-negative transition functions on ,

The notation is standard in reaction network literature [3], where we find our primary source of applications. For convenience, we let

| (2.1) |

The transition functions define a -matrix with , , and subsequently, a class of CTMCs on by assigning an initial state . Since is finite, there are at most finitely many jumps from any . For convenience, we identify the class of CTMCs with .

A state is reachable from if there exists a sequence of states , such that , and with , . It is accessible if it is reachable from some other state. The state is absorbing if no other states can be reached from it. A set is a communicating class of if any two states in can be reached from one another, and the set cannot be extended while preserving this property. A state is a neutral state of if it is an absorbing state not accessible from any other state, a trapping state of if it is an absorbing state accessible from some other state, and an escaping state of if it forms its own communicating class and some other state is accessible from it. A set is a positive irreducible component (PIC) of if it is a non-singleton closed communicating class, and a quasi-irreducible component (QIC) of if it is a non-singleton open communicating class.

Let , , , , and be the (possibly empty) set of all neutral states, trapping states, escaping states, PICs and QICs of , respectively. Each state has a unique type, hence , , , , and form a decomposition of the state space into disjoint sets.

A non-zero measure on a closed irreducible component of is a stationary measure of if is invariant for the -matrix, that is, if is a non-negative equilibrium of the master equation [13]:

| (2.2) |

and a stationary distribution if it is a stationary measure and . Furthermore, we say is unique, if it is unique up to a scaling constant. We might leave out ‘on ’ and just say is stationary measure of , when the context is clear.

2.3. Stochastic reaction networks (SRNs)

For clarity, we only introduce one-species SRNs and not SRNs in generality [3], as one-species SRNs are our primary application area. A one-species SRN is a finite labelled digraph with an associated CTMC on . The elements of are reactions, denoted by , where are complexes and the label is a non-negative intensity function on . Each complex is an integer multiple of the species S, that is, for some . In examples, we simply draw the reactions as in the following example with , and four reactions:

| (2.3) |

For convenience, we represent the complexes as elements of via the natural embedding, , and number the reactions as in the example above. The associated stochastic process can be given as

where are independent unit-rate Poisson processes and are intensity functions [3, 10, 25]. By varying the initial species count , a whole family of Markov chains is associated with the SRN.

A common choice of intensity functions is that of stochastic mass-action kinetics [3],

where is the reaction rate constant of the th reaction, and the combinatorial factor is the number of ways molecules can be chosen out of molecules (with order). This intensity function satisfies the stoichiometric admissibility condition:

( is taken component-wise). Thus, every reaction can only fire when the copy-numbers of the species in the current state are no fewer than those of the source complex.

We will assume mass-action kinetics in many examples below and label the reactions with their corresponding reaction rate constants, rather than the intensity functions. To bring SRNs into the setting of the previous section, we define

3. A classification result

In this section, we classify the state space into different types of states. In particular, we are interested in characterising the PICs in connection with studying stationary measures. Our primary goal is to understand the class of one-species SRNs, which we study by introducing a larger class of Markov chains embracing SRNs.

We assume throughout that a class of CTMCs associated with is given. Define

as the sets of positive and negative jumps, respectively. To avoid trivialities and for regularity, we make the following assumptions.

Assumptions.

-

(A1)

is finite, and .

-

(A2)

For , there exists such that if and only if

Then, is the smallest state for which a jump of size can occur ( is for input). If either of and is empty, then the chain is either a pure death or a pure birth process. Assumption (A1) and (A2) are fulfilled for stochastic mass-action kinetics.

For the classification, we need some further quantities. Let be the smallest possible ‘output’ state after applying a jump of size , and let

Any state is a trapping or neutral state (no jumps can occur from one of these states), and is the smallest state for which a forward jump can occur. Similarly, is the smallest state that can be reached from any other state and , the smallest state that can be reached by a backward jump.

In example (2.3), all jumps are multiples of , that is, the Markov chain is on or , depending on the initial state. Generally, the number of infinitely large irreducible classes is , the greatest positive common divisor of ( in example (2.3)). The following classification result is a consequence of [29, Corollary 3.15].

Proposition 3.1.

Assume (A1)-(A2). Then

Furthermore, the following hold:

-

(1)

If , then , and , , are the PICs,

-

(2)

If , then , and , , are the QICs,

-

(3)

If , then , , are the PICs, and , , are the QICs. .

In either case, there are PICs and QICs in total. When PICs exist, these are indexed by , and if and only if .

Proof.

We apply [29, Corollary 3.15]. To translate the notation of the current paper to that of [29, Corollary 3.15], we put , , , , and . Then, the expressions of , , and naturally follow. As in [29], define the following sets,

Since for ,

we have , and . If , these conclusions follow easily; if , then , and the conclusions follow.

According to [29, Corollary 3.15], it follows that

| (3.1) |

are the disjoint PICs and the disjoint QICs of , respectively, in the terminology of [29]. Consequently, as ,

Since, for ,

then we might state (3.1) as

We show that the expressions given for correspond to those given for in the three cases, by suitable renaming of the indices. First, note that if and only if . From and , we have , which yields . Consequently, and . This proves the expression for in (1).

Otherwise, if , then , which implies that . Hence, . If , then , which proves the expression for in (2). It remains to prove the last case. If , then

If , then using the above equation and , the expression for in (3) follows directly, and the remaining irreducible classes must be QICs. Finally, we show is impossible, which concludes the proof. Assume oppositely that . Then, , , and . This implies one can jump from the state (smallest state for which a backward jump can be made) leftwards to a state . The latter inequality comes from and . However, this implies , which is impossible.

The total number of PICs and QICs follows from . The indexation follows from in the two case (1) and (3). Also, the inequality follows straightforwardly in these two cases. It remains to check that it is not fulfilled in case (2). In that case, by assumption, hence , and the conclusion follows. ∎

In either of the three cases of the proposition, the index is the smallest element of the corresponding class (PIC or QIC). The role of Assumption (A2) in Proposition 3.1, together with Assumption (A1), is to ensure the non-singleton irreducible classes are infinitely large. If the assumption fails there could be non-singleton finite irreducible classes, even when .

A stationary distribution exists trivially on each element of . If the chain starts in , it will eventually be trapped into a closed class, either into or , unless absorption is not certain in which case it might be trapped in . If absorption is certain it will eventually leave . We give two examples of CTMCs on showing how the chain might be trapped.

Example 3.2.

(A) The reaction network has , , , (note that there are two reactions with jump size ). Hence , and . It follows from Proposition 3.1 that , , , , and . There is only one infinite class, which is a QIC. From the escaping state, one can only jump backward to the trapping state. The escaping state is reached from .

(B) The reaction network has , , , (note that there are two reactions with jump size ). Hence, , and . It follows from Proposition 3.1 that , , , and . There is only one infinite class, which is a PIC. From the escaping state, one can only jump forward to this PIC.

4. Characterization of stationary measures

We present an identity for stationary measures based on the flux balance equation [17], see also [31]. It provides means to express any term of a stationary measure as a linear combination with real coefficients of the generating terms. The coefficients are determined recursively, provided (A1) and (A2) are fulfilled.

To smooth the presentation we assume without loss of generality that

-

(A3)

, and .

Hence, we assume is a PIC and remove the index from the notation for convenience. For general with and , we translate the Markov chain to one fulfilling (A3) for each by defining by (element-wise multiplication) and with , . Hence, there are no loss in assuming (A3). We assume - throughout Section 4 unless otherwise stated.

Let be any stationary measure of on . Define to be the largest positive and negative jump sizes, respectively,

| (4.1) |

We will show that can be expressed as a linear combination with real coefficients of the generating terms , where

| (4.2) |

are the lower and upper numbers, respectively. Hence, as a sum of terms. No backward jumps of size can occur from any state , and is the smallest output state of a jump of size .

Example 4.1.

(A) Consider the reaction network, In this case, , , and (A3) does not apply. In fact, with PICs and , respectively. After translation, we find , , and , , where the index refers to . Thus, the lower and upper numbers are not the same for each class. (B) The reaction network, has , . Hence, with PIC , and (A3) applies. We find . Thus, the lower and upper numbers might be arbitrarily large depending on the SRN.

Before presenting the main results, we study an example.

Example 4.2.

Recall Example 4.1(B) with mass-action kinetics, , and reactions

According to [30, Theorem 7], this SRN is positive recurrent on for all and hence, it has a unique stationary distribution. We have , .

By rewriting the master equation (2.2), we obtain

the latter for . There is not an equation that expresses in terms of the lower states as the state can only be reached from and . Consequently, and can be found from and , but not vice versa, and , is determined recursively from and using the last equations above, say, , where the coefficients depend on the intensity functions. For , these follow from the first equations (see also Theorem 4.4 below),

while for , we obviously have , where is the Kronecker symbol. For , the coefficients are given recursively, see Theorem 4.4 for the general expression. A recursion for cannot be given in terms of alone.

First, we focus on the real coefficients of the linear combination. From Example 4.2 we learn that the coefficients take different forms depending on the state, which is reflected in the definition of below. For convenience, rows and columns of a matrix are indexed from .

By the definition of and , any state is reachable from at most other states in one jump. For this reason, let

| (4.3) |

(as , ), and define the functions

by

| (4.4) |

where the functions are defined by

| (4.5) | ||||

| (4.6) | ||||

| (4.7) |

(note that is not used in the definition of , but appears in the proof of the Proposition 4.3 below), and is an matrix defined from the matrix with entries

| (4.8) |

where is dimensional and is dimensional. Note that is the empty matrix if or . In (4.8), we adopt the convention stated in (2.1). In particular, for . By definition, is the row reduced echelon form of by Gaussian elimination, where is the identity matrix.

The functions and the sets come out of the flux balance equation, that is an equivalent formulation of the master equation [17]. We use it in (4.10) in the proof of Proposition 4.3. For each , it provides an identity between two positive sums, one over terms evaluated in at most states with values , and one over terms evaluated in at most states with values . The function is well defined for if (A1), (A2) are fulfilled. In that case, , see Lemma A.1. The matrix is well defined with invertible under the assumptions (A1), (A2), provided and , see Lemma A.2.

Proposition 4.3.

Proof.

We recall an identity related to the flux balance equation [17] for stationary measures for a CTMC on the non-negative integers [31, Theorem 3.3], which is a consequence of the master equation (2.2): A non-negative measure (probability measure) on is a stationary measure (stationary distribution) of if and only if

| (4.10) |

where it is used that , and the domain of as well as is extended from to (that is, , for ). Furthermore, the sets are defined by

If then all terms in both double sums in (4.10) are zero. In fact, (4.10) for is equivalent to the master equation (2.2) for .

Assume is a stationary measure of . Let , , and let with . Then, , and it follows that (4.10) is equivalent to

| (4.11) |

where if , and otherwise. It implies that

Hence, it also follows from the definition (4.7) of that

Thus, (4.11) is equivalent to

| (4.12) |

using the definition of . Since and (4.10) is trivial for , then (4.12) is also trivial for (all terms are zero). This proves the bi-implication and the proof is completed. ∎

For , all terms in (4.9) are zero, hence the identity is a triviality. We express in terms of the generating terms, .

Theorem 4.4.

A non-zero measure on is a stationary measure of on if and only if

| (4.13) |

where is defined as in (4.4).

Proof.

Assume is a stationary measure. The proof is by induction. We first prove the induction step. Assume (4.13) holds for and all such that . Then, from Proposition 4.3, (4.4), (4.5), (4.6), and the induction hypothesis, we have

We next turn to the induction basis. For , (4.13) holds trivially as in this case. It remains to prove (4.13) for . Since is a stationary measure it fulfils the master equation (2.2) for . By rewriting this, we obtain

The denominator is never zero because for , it holds that for at least one (otherwise zero is a trapping state).

In particular, for , using (4.2), it holds that . Hence, , and

Now, defining , we have for , using , see (4.2). Hence

with the convention in (2.1). Evoking the definition of in (4.8), this equation may be written as

Recall that with . Noting that , , yields that (4.13) is fulfilled with , and , and the proof of the first part is concluded.

For the reverse part, we note that for , the argument above is ‘if and only if’: if and only if the master equation (2.2) is fulfilled for . As noted in the proof of Proposition 4.3, this is equivalent to (4.10) being fulfilled for , which in turn is equivalent to (4.12) being fulfilled for (the equation is replicated here),

| (4.14) |

As , then (4.14) holds for .

For completeness, we apply Proposition 4.3 to Example 4.2. The SRN has and , such that . Equation (4.14) for becomes

in agreement with the equations found in Example 4.2.

4.1. Matrix representation

A simple representation can be obtained in terms of determinants of a certain matrix. For an infinite matrix , let , , denote the matrix composed of ’s first rows and columns.

Theorem 4.5.

The function , , has the following determinant representation for ,

where the matrix is the infinite band matrix,

and

Proof.

For the first equality, we apply [19, Theorem 2] on the solution to a -th order linear difference equation with variable coefficients. First, from (4.4), we have for that

as . Thus, for , we have

| (4.15) |

subject to the initial conditions for , given in (4.4).

Secondly, we translate the notation used here into the notation of [19, Theorem 2]: , , . Furthermore, we take , and . Then, the condition of [19, Theorem 2] translate into (4.15). The matrix is as in [19, Theorem 2], except the first column is multiplied by . By [19, Theorem 2], we find that

By Lemma A.1, the second equality follows from , , see (4.5). ∎

A combinatorial representation can be achieved by calculating the determinant. In the present case, the matrix is a Hessenberg matrix and an explicit combinatorial expression exists [22, Proposition 2.4]. Combining Theorem 4.4 and Theorem 4.5 yields the following.

Corollary 4.6.

Let be a stationary measure of on . Then,

Example 4.7 (Upwardly skip-free process).

Consider the SRN with mass-action kinetics,

Here, and , for . Hence, , , . Consequently, , and (A3) is fulfilled, in addition to (A1)-(A2). According to [30, Theorem 7], the SRN is positive recurrent on for all , and hence has a unique stationary distribution.

Example 4.8 (Downwardly skip-free process).

Consider the SRN with mass-action kinetics,

Here, and , for . Hence, , , . Consequently, , and (A3) is fulfilled, in addition to (A1)-(A2). According to [30, Theorem 7], the SRN is positive recurrent on for all , and hence has a unique stationary distribution.

5. Skip-free Markov chains

5.1. Downwardly skip-free Markov chains

An explicit iterative formula can be derived from Theorem 4.4 for downwardly skip-free Markov chains.

Corollary 5.1.

Assume , and let . Then, is a stationary measure of on if and only if

where

and is as defined in (4.5). Consequently, there exists a unique stationary measure of on . Furthermore, if is a stationary distribution, then .

Proof.

Since , then , see (4.2). Moreover, as otherwise the state zero could not be reached. Hence, from (4.2). Consequently, , , from Theorem 4.4. Furthermore, such that the expression for , , follows from (4.4). Positivity of , , follows from Theorem 6.3. If is a stationary distribution, then , and the conclusion follows. ∎

Corollary 5.1 leads to the classical birth-death process characterization.

Corollary 5.2.

Assume . A measure on is a stationary measure of on if and only if

where in the case of a stationary distribution.

5.2. Upwardly skip-free Markov chains

In general, we are not able to give conditions for when an upwardly skip-free Markov chain has a unique stationary measure (up to a scalar) and when it has more than one or even infinitely many linearly independent ones. However, in a particular case, if there is not a unique stationary measure, we establish all stationary measures as an explicit one-parameter family of measures (Corollary 5.5). If the transition functions are polynomial then we show a stationary measure is always unique (Corollary 5.6). Thus, we need non-polynomial transition rates for non-uniqueness and give one such example in Example 9.5.

Proposition 5.3.

Assume and , hence . A non-zero measure on is a stationary measure of on if and only if

| (5.1) |

where

| (5.2) |

for , and

| (5.3) |

with for convenience if there are no jumps of size . If this is the case, then

| (5.4) |

Proof.

Recall the master equation for a stationary measure , in the form of (4.11):

| (5.5) |

Define and as in the statement for (if , then might be zero; if , then division by zero occurs as ). Dividing on both sides of (5.5) yields

and the identity (5.1) follows. By rewriting the master equation, then (5.3) follows. The calculations can be done in reverse order yielding the bi-implication. Equation (5.4) follows by induction. ∎

Lemma 5.4.

Let and be functions with , and such that

| (5.6) |

Let be a positive number. Then, is a positive function with , if and only if

where , , and is determined recursively by

| (5.7) |

with .

Proof.

Let be as in the statement and a positive function fulfilling (5.6). Note that is the -th convergent of a generalized continued fraction, hence is increasing in and is decreasing in . Indeed, this follows from Theorem 4 (monotonicity of even and odd convergents) of [18]. See also the proof of Corollary 5.5.

By induction, we will show that

from which it follows that

| (5.8) |

For the base case, it follows from (5.6) that for , and thus

For the induction step, assume for and some . Then, using (5.7),

If , then the first implication follows from (5.8). For the reverse implication, assume Note from (5.6) that is positive only if . We will show that implies for all , hence also for all , and we are done. Letting in (5.7) yields

Hence, it follows from the induction hypothesis that

using (5.6), and the claim follows. ∎

Below, we give a general condition for uniqueness and show that uniqueness does not always hold by example. In Section 6, we give concrete cases where uniqueness applies.

Corollary 5.5.

Assume and . Choose and where are as in Lemma 5.4 and as in (5.2). Let be a solution to (5.6) in Lemma 5.4 with . Then, (5.4) and (5.3) define a stationary measure of on by setting .

The measure is unique if and only if , if and only if the following sum is divergent for ,

where

Proof.

The first part of the proof is an application of Proposition 5.3 and Lemma 5.4 with . The last bi-implication follows by noting that in Lemma 5.4 is the -th convergent of a generalized continued fraction,

that is, , . By transformation, this generalized continued fraction is equivalent to a (standard) continued fraction,

with

By [18, Theorem 10], the continued fraction converges if and only if , which proves the bi-implication, noting that by the first part of the proof it is sufficient to check , and using the concrete form of in (5.2). ∎

Corollary 5.6.

Assume , , and that , , is a polynomial for large . Then, there is a unique stationary measure of on .

Proof.

We prove that the first series in in Corollary 5.5 diverges for , and hence . Let , . We first provide asymptotics of for large . By the Euler-Maclaurin formula with ,

where for all , and are positive constants depending on . This implies that the terms in the first series of are bounded uniformly in from below:

and hence the first series in diverges. ∎

6. Invariant vectors and existence of stationary measures

In the previous section, we focused on non-zero measures on and conditions to ensure stationarity. However, the requirement of a non-zero measure is not essential. In fact, the conditions of Proposition 4.3 and Theorem 4.4 characterize equally any real-valued sequence that solves the master equation (2.2). Henceforth, we refer to the vector as a generator and the sequence as an invariant vector. This implies the linear subspace in of invariant vectors is -dimensional. Such vector might or might not be a signed invariant measure depending on whether the positive or the negative part of the vector has finite one-norm.

We assume (A1)-(A3) throughout Section 6. If the CTMC is recurrent (positive or null), then it is well known that there exists a unique stationary measure. For transient CTMCs, including explosive chains, there also exists a non-zero stationary measure in the setting considered.

Proposition 6.1.

There exists a non-zero stationary measure of on .

Proof.

Lemma 6.2.

Let be a non-zero invariant measure of on such that for all . Then, for all . In fact, is a non-zero stationary measure of .

Proof.

Assume . By rewriting the master equation (2.2), we obtain

Let be reachable from in steps. If , then it follows from above that for some and . If , then by induction in the number of steps. Since is irreducible by assumption, then any state can be reached from any other state in a finite number of steps, and for all . However, this contradicts the measure is non-zero. Hence, for all . ∎

Theorem 6.3.

The sequences form a maximal set of linearly independent invariant vectors in . Moreover, has positive and negative terms for all if and only if , that is, if and only if . If , then has all terms positive. In any case, , for .

Proof.

The former part follows immediately from Theorem 4.4, since is the -th unit vector of , for , by definition. The latter part follows from Lemma 6.2 and the fact that and for . If , then the linear space is one-dimensional and positivity of all , , follows from Lemma 6.2 and the existence of a stationary measure, see Proposition 6.1. The equivalence between and follows from (4.2). If , then for any invariant vector , contradicting the existence of a stationary measure. ∎

Theorem 6.4.

Let be the set of generators of stationary measures of on . Then, is a positive convex cone. Let be the set including the zero vector, which generates the null measure. Then, is a closed set. The set is closed and convex.

Proof.

Part of Theorem 6.4 might be found in [8, Theorem 1.4.6]. In general, we do not have uniqueness of a stationary measure of on , unless in the case of recurrent CTMCs. For downwardly skip-free processes, we have , hence the space of signed invariant measures is one-dimensional and uniqueness follows, that is, there does not exist a proper signed invariant measure taking values with both signs.

We end the section with a few results on uniqueness of stationary measures. For this we need the following lemma.

Lemma 6.5.

Let be a non-zero generator and assume . Let

If, either

| (6.1) |

for some , or

| (6.2) |

for some , then

| (6.3) |

Proof.

Since , then . We use rather than in the proof for convenience. From Lemma A.1, we have for and , and for . The latter follows from and in this case. Furthermore, since defines an invariant vector, then from (4.9),

| (6.4) |

Assume (6.1) holds. If , then there is nothing to show. Hence, assume . By assumption the sum in (6.4) is non-positive, while the last term is non-negative and as . Hence, . Continue recursively for until . Note that for , in agreement with the conclusion.

Assume (6.2) holds. If , then there is nothing to prove. For , we aim to show (6.1) holds from which the conclusion follows. By simplification of (6.4),

If , then either and take the same sign or are zero. Consequently, a) for all , or b) for all . Similarly, if , then . Consequently, a) or b) holds in this case too. If a), then (6.3) holds. If b), then (6.3) holds with reverse inequality by applying an argument similar to the non-negative case. However, , , and at least one of them is strictly larger than zero, by assumption. Hence, the negative sign cannot apply and the claim holds. ∎

For , define the matrix by

where , and T denotes transpose. This matrix is well-defined by Theorem 6.3. The rows of , except the last one, has -norm one, and all entries are between and .

Theorem 6.6.

Assume there exists a strictly increasing subsequence , such that as , with .

1) There is at most one stationary measure of on , say , with the property

| (6.5) |

2) If and is a unique stationary measure of on , then (6.5) holds.

Proof.

1) Let

and let be the generator of the stationary measure . We have

as , where is the zero vector of length . Since is invertible, then

Consequently, as this holds for any stationary measure with the property (6.5), then is unique, up to a scalar.

2) According to Proposition 7.3 below, is invertible and there is a unique non-negative (component-wise) solution to

for all . It follows that

as , since . Define

then is non-negative and , since is non-negative, and as . We aim to show that is the generator of the unique stationary measure .

To state the next result, we introduce some notation. Let

If , then and . If , then by the definition of , and (Theorem 6.3). In general, it follows from Theorem 4.4, Proposition 6.1, and Lemma 6.2, that , and . In particular, for , that is, , then and . Below, in the proof of Lemma 6.7, we show these four sets are infinite. Hence, we may define

| (6.6) |

Lemma 6.7.

Assume , that is, . It holds that . A non-zero measure is a stationary measure if and only if

| (6.7) |

Furthermore, a stationary measure is unique if and only if , if and only if

| (6.8) |

If this is the case, then limes superior and limes inferior in (6.6) may be replaced by limes.

Proof.

Let be a stationary measure, which exists by Proposition 6.1. Then , which implies that

by taking supremum and infimum, respectively, this further implies

and that is in the interval . Note that and , since and are both non-empty, using Theorem 6.3. For the reverse conclusion, for any invariant vector such that (6.7) holds, we have using Theorem 4.4,

which implies that is a stationary measure, see Lemma 6.2.

Assume that either or is attainable for some . Then, there exists a stationary measure such that

that is, , contradicting the positivity of , see Lemma 6.2. Hence, and both contain infinitely many elements, and since neither nor are attainable, then and can be replaced by and , respectively, to obtain and in (6.6). Hence, also and are infinite sets, since and .

For the second part, the bi-implication with is straightforward. Assume is a stationary measure, such that . Note that

as otherwise for some large . For ,

| (6.9) | ||||

for some small and large . Similarly, for ,

| (6.10) | ||||

for and large . Taking over in (6.9) and over in (6.10), using (6.8), yields

or with replaced by . Hence, (6.6) holds with and replaced by . It follows that and that is unique. For the reverse statement, change the first inequality sign in (6.9) and (6.10) to , and and to one, and the conclusion follows. ∎

7. Convex constrained optimization

When the Markov chain is sufficiently complex, an analytical expression for a stationary measure may not exist. In fact, this seems to be the rare case. If an analytical expression is not available, one may find estimates of the relative sizes of , which in turn determines , , up to a scaling constant, by Theorem 4.4. If is a stationary distribution, this constant may then be found numerically by calculating the first probabilities , , for some , and renormalizing to obtain a proper distribution. Here, we examine how one may proceed in practice.

Theorem 7.1.

Assume (A1)-(A3) and for , let

| (7.1) |

Then, , , , and is non-empty and consists of all generators of non-zero stationary measures of on , appropriately normalized. In fact, with as in Theorem 6.4.

Furthermore, there is a unique minimizer to the following constraint quadratic optimization problem,

| (7.2) |

Moreover, the limit exists and equals the generator of a stationary measure of on , that is, .

Proof.

The sets are non-empty by Proposition 6.1 and obviously non-increasing: . Hence, since all s have a common element, the intersection is also non-empty. Lemma 6.2 rules out the intersection contains boundary elements of .

Furthermore, the sets are non-empty, closed and convex. Since is strictly convex, there exists a unique minimizer for the constrained optimization problem (7.2) [6, p137 or Ex 8.1 on p.447].

Since the sets are non-increasing, then is non-decreasing in -norm: for all . Furthermore, since the sets are closed subsets of the simplex and hence compact, any sequence , , of minimizers has a converging subsequence , , say (the intersection is closed). To show uniqueness, suppose there is another converging subsequence , , such that and . Then, it follows that , since the norm is non-decreasing along the full sequence. By convexity of , the intersection is convex and for . By strict convexity of the norm and , then

| (7.3) |

Let . By convexity and monotonicity of , we have

By assumption, . Hence, , contradicting (7.3). Consequently, .

Since , then for some non-zero stationary measure of on . ∎

If the process is downwardly skip-free, then and might be put to one. Consequently, , , can be found recursively from (4.13). Hence, it only makes sense to apply the optimization scheme for .

The quadratic minimizing function is chosen out of convenience to identify a unique element of the set . Any strictly convex function could be used for this. If there exists a unique stationary measure, then one might choose a random element of as any sequence of elements in , , eventually converges to the unique element of . If there are more than one stationary measure, different measures might in principle be found by varying the convex function. In the case, two different stationary measures are found, then any linear combination with positive coefficients is also a stationary measure.

In practice, the convex constrained optimization approach outlined in Theorem 7.1 often fails for (not so) large , see the example in Section 9. This is primarily because the coefficients become exponentially large with alternating signs, and because numerical evaluation of close to zero probabilities might return close to zero negative values, hence violating the non-negativity constraint of the convex constrained optimization problem. The numerical difficulties in verifying the inequalities are non-negative are most severe for large , in particular if vanishes for large . To face the problems mentioned above, we investigate an alternative approach to the optimization problem.

Lemma 7.2.

Assume (A1)-(A3). Define the sets , , by

If , then there is a unique minimizer to the following constraint quadratic optimization problem,

Moreover, if , then is a singleton set, and for , where is as in (7.1). Furthermore, if there exists a unique stationary measure of on , then exists. In particular, equals the generator of , that is, , appropriately normalized.

Proof.

Existence of the minimizer follows similarly to the proof of Theorem 7.1. If , then it follows from Proposition 7.3 below that is a singleton set for . It follows from Lemma 6.5 that . Since , and contains the generator of the unique stationary measure only, then exists and equals the generator of . ∎

We refer to the optimization problem outlined in Lemma 7.2 as the linear approximation scheme. For , a solution to the linear appproximatioin scheme automatically fulfils for all . In general, these inequalities need to be validated.

Proposition 7.3.

If , then , , is a singleton set.

Proof.

For , let be the matrix,

and let be the cofactor of corresponding to the -th row and -th column, for . Then, , and there exists a unique solution to , where is the -th unit vector in , if and only if . If this is the case, then by Cramer’s rule,

and hence if and only if all cofactors have the same sign or are zero. Hence, we aim to show at least one cofactor is non-zero and that all non-zero cofactors have the same sign. In the following, for convenience, we say the elements of a sequence have the same sign if all non-zero elements of the sequence have the same sign.

For , define the matrix

and the matrices , , by removing row of (that is, the -th row counting from the bottom). For notational convenience, noting that the columns of take a similar form, we write these matrices as

Note that

| (7.4) |

Let be the matrix obtained by removing the bottom row and the -th column from . Hence, the cofactor of corresponding to the -th row and -th column is

| (7.5) |

. By induction, we will show that the signs of , , are the same, potentially with some cofactors being zero, but at least one being non-zero.

Induction basis. For , we have

and it follows by tedious calculation that

and . It follows that the s have the same sign for fixed and all (all cofactors are zero, except for ).

We postulate that the non-zero elements fulfil

and , . The hypothesis holds for .

Induction step. Assume the statement is correct for some . Using and (4.4), we obtain for (excluding ),

Hence, using the linearity of the determinant, we obtain for (excluding ),

with the remaining terms from the linear expansion of the determinant are zero. In the computation of the determinant above, we abuse for the row vector with the -th coordinate deleted. For , then using (7.4),

The above conclusions result in the following for the sign of the cofactors, using (7.5):

| (7.6) | ||||

| (7.7) |

We recall some properties of . According to Lemma A.1(vi), for , using (otherwise zero is a trapping state) and . For , we have , and hence for , according to Lemma A.1(vii)-(viii). Consequently, the sign of the two terms in (7.6) are:

hence the sign of corroborates the induction hypothesis. The sign of the term in (7.7) is

again in agreement with the induction hypothesis.

It remains to show that at least one cofactor is non-zero, that is, for at least one and . Let . From (7.4) and (7.6), we have

| (7.8) | ||||

for We show by induction that for and . Hence, the desired conclusion follows. For , we have for all . Assume for and some . Since for , then it follows from (7.8) that for . The proof is completed. ∎

8. The generating function

In this and the next section, we consider one-species SRNs mainly with mass-action kinetics, without assuming (). That is, we allow for multiple PICs indexed by and general . For a stationary measure of on a PIC (for some ), we define

| (8.1) |

Then, is a stationary measure of on for the translated Markov chain as in Section 4. Similarly, we add the superscript to , whenever convenient. These quantities are already expressed in terms of the translated Markov chain.

For one-species SRNs with mass-action kinetics, one might represent the stationary distribution (when it exists) through the probability generating function (PGF). Recall that for a random variable on with law , the PGF is:

such that

where is the -th derivative of .

Proposition 8.1.

Let a one-species SRN fulfilling (A1) with mass-action kinetics be given, hence (A2) also holds. Assume there exists a stationary distribution on , for some . Let , , be the corresponding distribution on and the PGF of . Then, solves the following differential equation:

Proof.

Recall that is an equilibrium of the master equation:

Multiplying through by and summing over , we obtain

Using the form of mass-action kinetics, and rearranging terms,

where . Here, we have used that for , and if , then , which implies that for . As , we may write this as

whence upon collecting terms yields the desired. ∎

Since

we arrive at the following alternative expression for the stationary distribution.

Example 8.3.

Consider the SRN with mass-action kinetics,

with . This is an upwardly skip-free process: , , , , , .

Applying Proposition 8.1, the governing differential equation of the PGF is,

that is,

| (8.2) |

Let and , then (8.2) yields the Kummer differential equation [1]:

Taking ,

where

is the confluent hypergeometric function (also called Kummer’s function) of the first kind [1], and is the ascending factorial. Using the relation between Kummer’s function and its derivatives

it follows that

In particular, if and only if is a Poisson distribution,

When this is the case, the reaction network is complex balanced and the form of the stationary distribution is well known [2].

9. Examples

To end we present some examples using the linear approximation scheme and the convex constrained optimization approach. We use the criteria in [30, Theorem 7] to check whether a CTMC with polynomial transition rates is positive recurrent, null recurrent, transient and non-explosive, or explosive. These properties hold for either all PICs or none, provided the transition rate functions are polynomials for large state values, as in mass-action kinetics [30, Theorem 7].

We have made two implementations of the numerical methods. One in R and one in Python (only mass-action kinetics) with codes available on request. In all examples, the code runs in few seconds on a standard laptop. The two codes agree when run on the same example. We have not aimed to optimize for speed. In figures, ‘State ’ refers to the state of the original Markov chain, and ‘Index ’ refers to the translated Markov chain, the index of, for example, . The index refers to the irreducibility class in Proposition 7.3.

Example 9.1.

Consider the SRN with mass-action kinetics,

We have and with (zero is a neutral state), and . Furthermore, a unique stationary distribution exists since the SRN is positive recurrent for all positive rate constants [30, Theorem 7], and . As the reaction network is weakly reversible (the reaction graph consists of a finite union of disjoint strongly connected components), then it is complex balanced for specific choices of rate constants, yielding a Poisson stationary distribution [2]. This is the case if and only if .

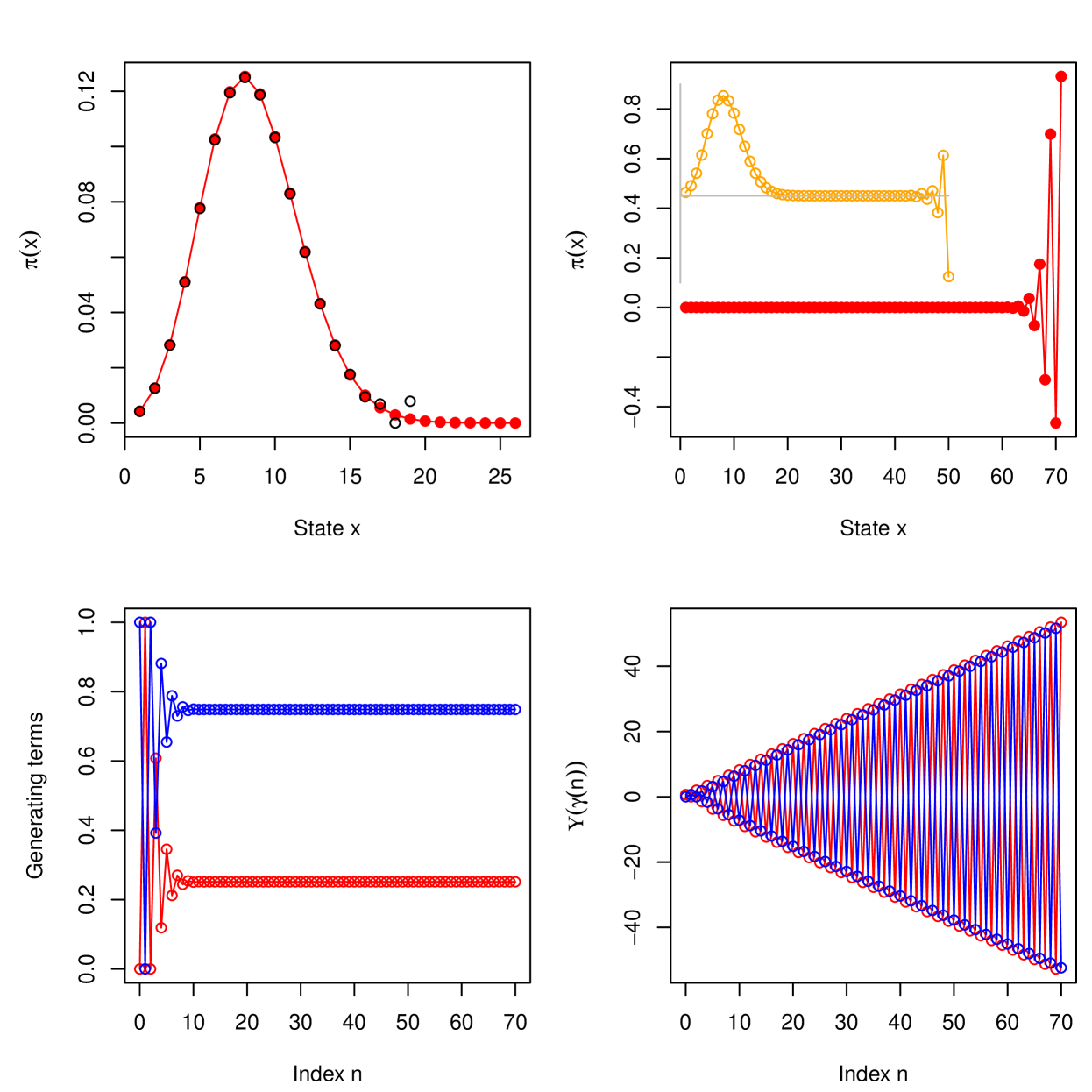

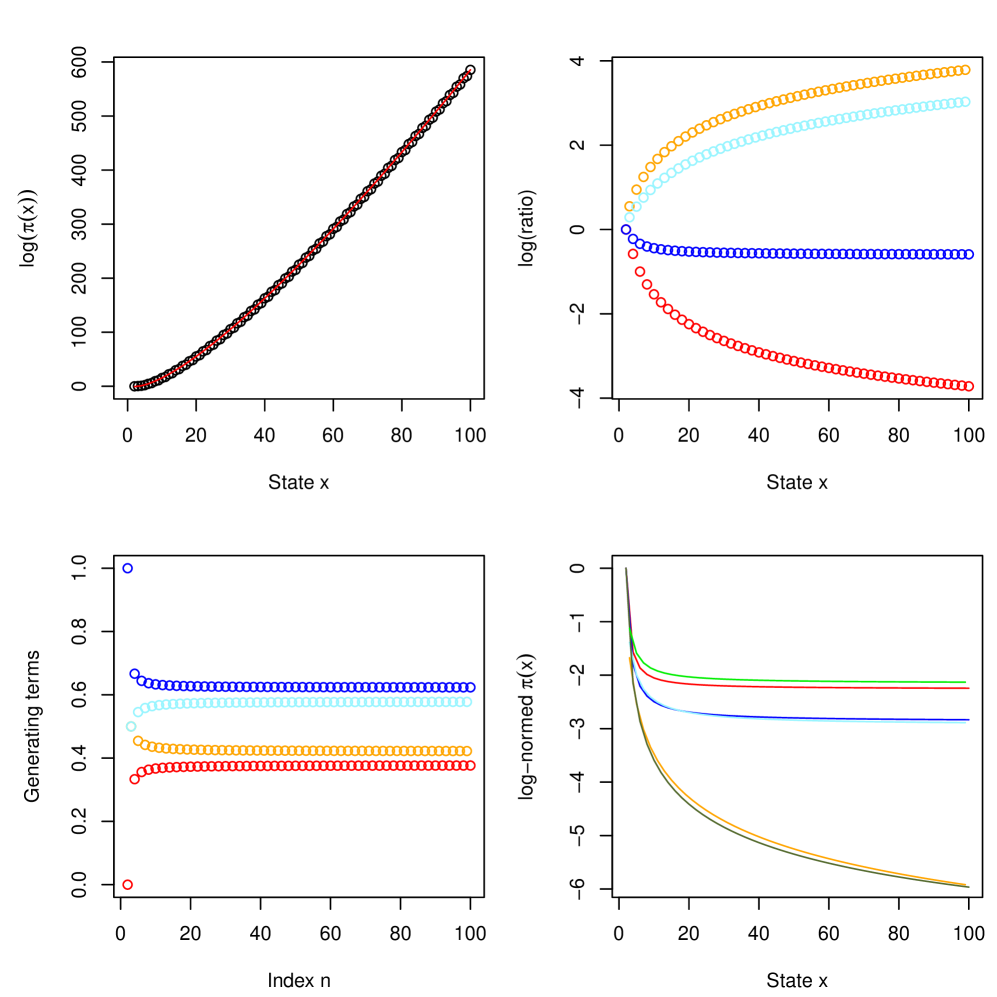

Here, we focus on the stability of the numerical approximations using the linear approximation scheme and convex constrained optimization for a single set of parameters, , see Figure 1. Convex constrained optimization fails for in (7.2) due to exponentially increasing values with alternating signs. In contrast, the linear approximation scheme is quite robust and returns accurate estimates for the generating terms (, even for . However, in this situation, inaccurate and negative probability values for large state values are returned, see Figure 1. The estimated values of and are zero to the precision of the computer and the first negative estimate is . From then on, the estimated probabilities increase in absolute value. The estimated generating terms for the convex constrained optimization problem with and the linear approximation scheme with deviate on the seventh decimal point only. In the latter case, the estimates remain unchanged for for up to seven decimal points, despite negative probabilities are found for large .

It is remarkable that for with of the order , we still numerically find that is a singleton set, as postulated in Proposition 7.3, despite the solution gives raise to instabilities in calculating the probabilities. Also the numerical computations confirm that the limit in (6.8) in Lemma 6.7 is zero, as increases beyond bound.

The following example demonstrates that both the linear approximation scheme and the convex optimization approach can be efficient in practice for ergodic CTMCs.

Example 9.2.

For the SRN with mass-action kinetics,

| (9.1) |

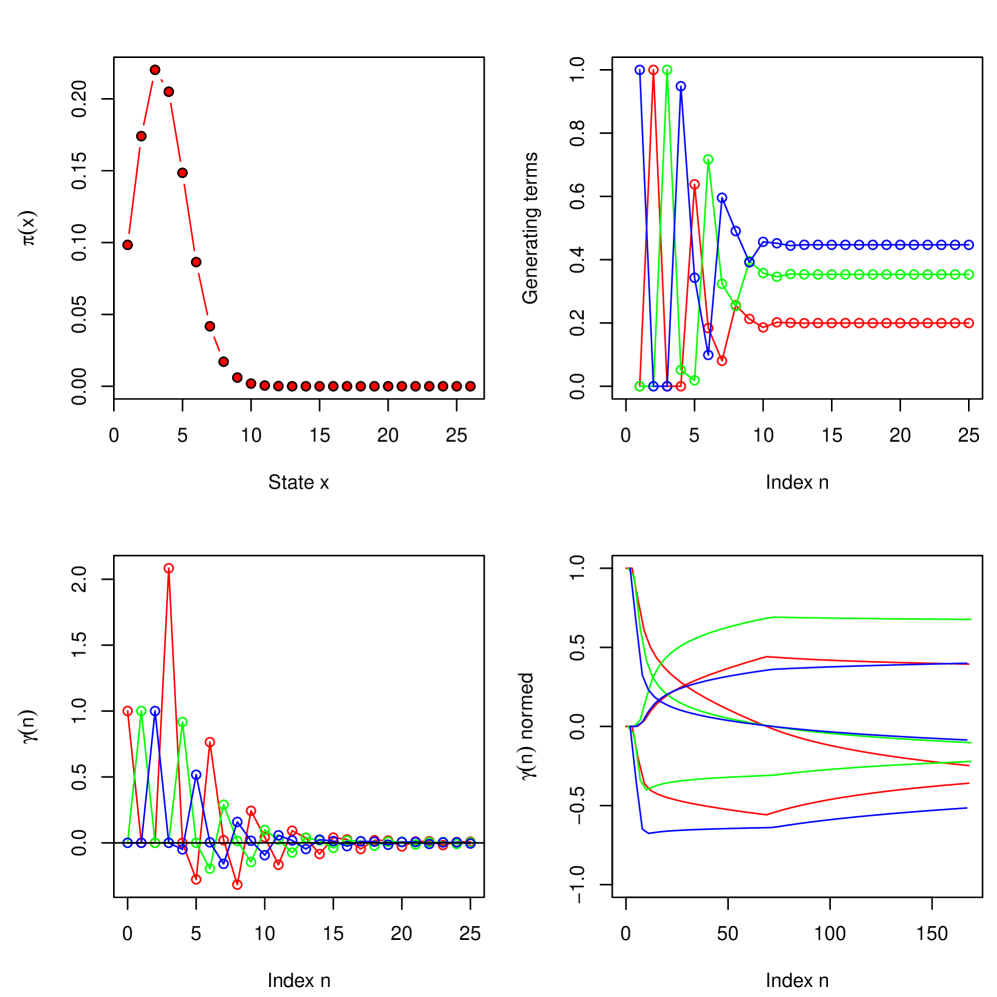

we obtain , , and , , , such that there is one PIC with state space . Despite Proposition 7.3 does not apply (as ), numerically we find that is a singleton set. Using the linear approximation scheme or the convex optimization approach, we obtain a rather quick convergence, see Figure 2. In this case, the coefficients , , decrease fast towards zero, taking both signs. Both algorithms run efficiently even for large as the coefficients vanish. The bottom right plot in Figure 2 shows . There appears to be a periodicity of , demonstrating numerically that the matrices , and , , each converges as , see Theorem 6.6. The generator recovered from either of the three sequences , and agree to high accuracy, and agree with the generator found using the linear approximation scheme.

Although, in theory, it seems to make sense to use the linear approximation scheme only for stationary measures for which is vanishing. In practice, it seems that the linear approximation scheme still captures the feature of a stationary measure with non-vanishing decently, when the states are not too large.

Example 9.3.

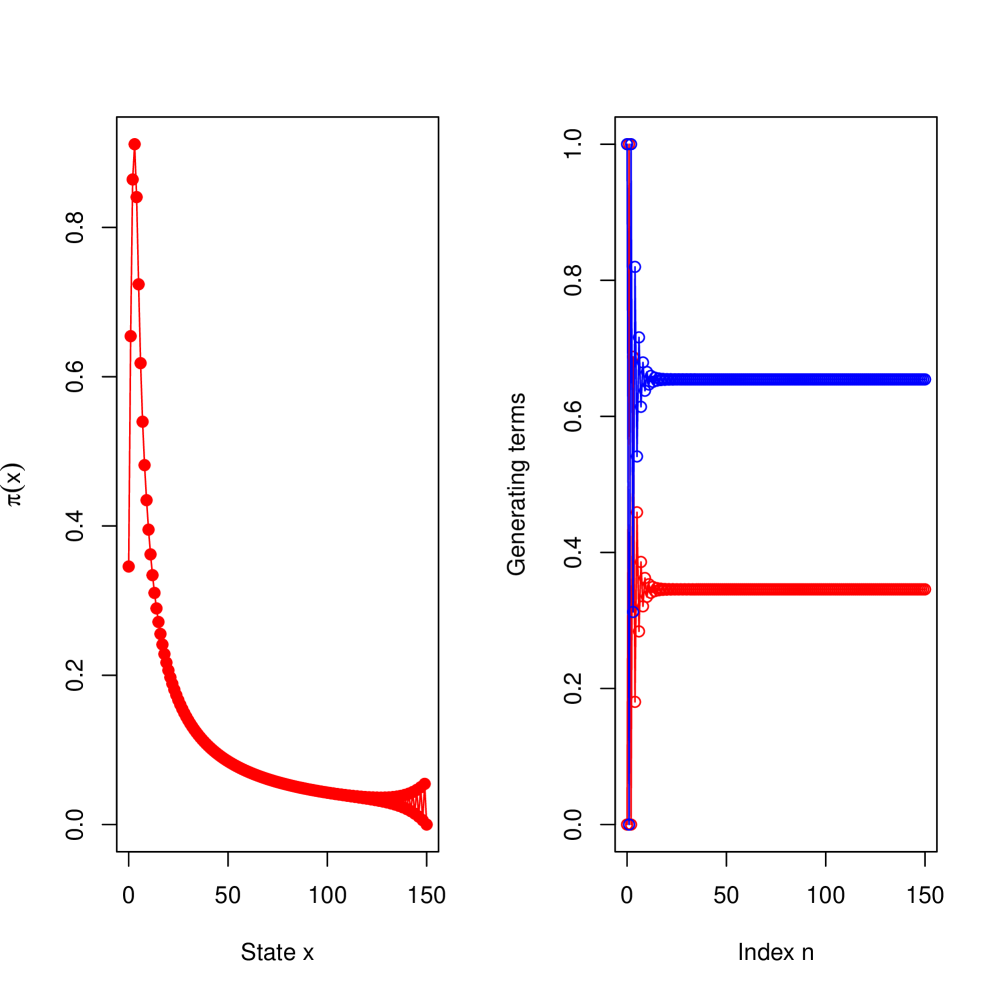

Computing an unknown distribution. We give an example of a mass-action SRN,

which is null recurrent by the criterion in [30, Theorem 7], and hence there exists a unique stationary measure due to [25, Theorem 3.5.1] and [7, Theorem 1]. In this case, and . Furthermore, and , . We apply the linear approximation scheme to the SRN with and find that is a singleton set, despite , see Proposition 7.3. For large states the point measures are considerably far from zero, see Figure 3. Moreover, instabilities occur. The inaccuracies in the values are due to small inaccuracies in the estimation of the generating terms and the large coefficients that increases exponentially.

We know from Corollary 5.6 that there exists a unique stationary measure for CTMCs with polynomial transition rates if and , it remains to see if such a stationary measure is finite. With the aid of our numerical scheme, we might be able to infer this information in some scenarios.

Example 9.4.

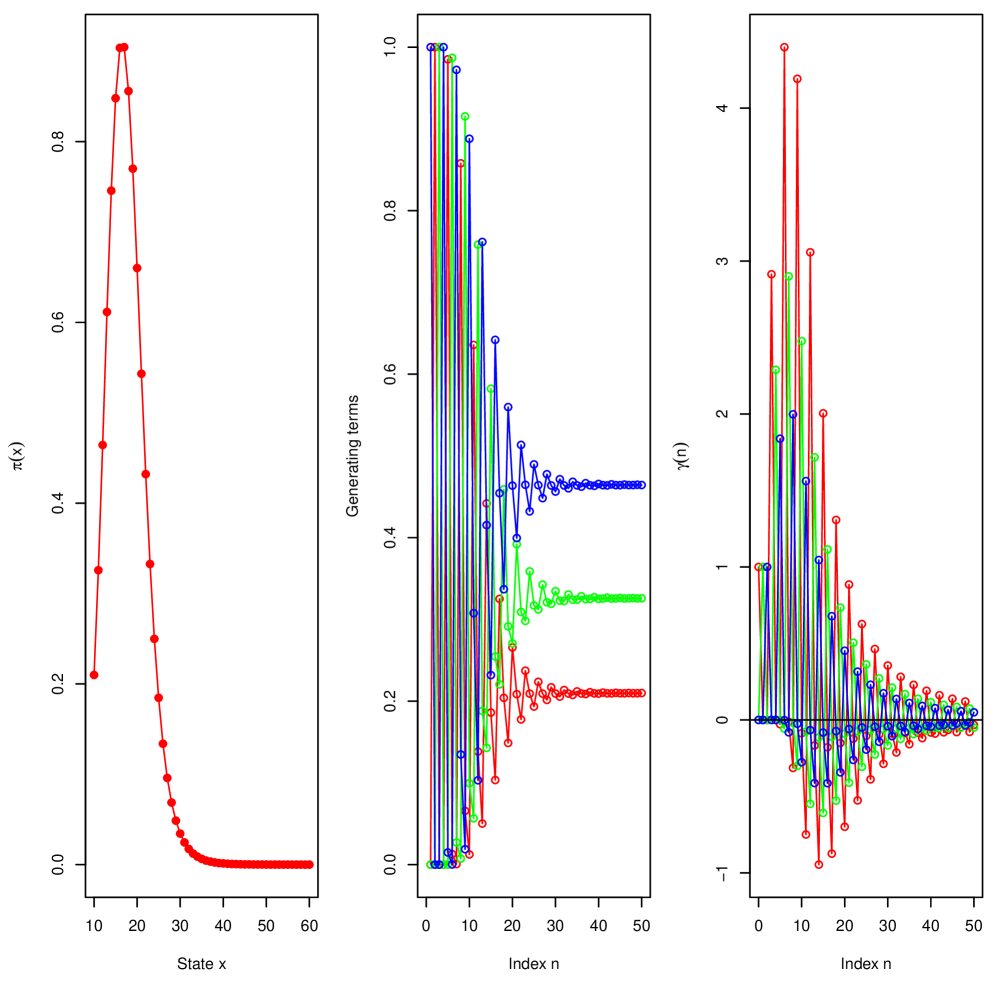

Computing an unknown measure. Consider the following SRN,

It is explosive by the criterion in [30, Theorem 7]. We have , , , and . The linear approximation scheme retrieves what appears to be a stationary distribution, see Figure 4. The numerical computations confirm that the limit in (6.5) in Theorem 6.6 is zero, pointing to the stationary distribution being unique.

We end with an example for which there exists more than one stationary measure.

Example 9.5.

Consider the SRN with reactions , , and

Then, (A1)-(A3) are fulfilled with , , , , (so ). From Corollary 5.5 with ,

Consequently, there is not a unique stationary measure of on . Numerical computations suggest that using (5.7) with . See Corollary 5.5 for a definition of .

In the following, we will explore the stationary measures using the theory of Section 5.2 and compare it to results obtained from the linear approximation scheme. For any stationary measure , by definition of and , we have for ,

hence

for some constant , and is not a distribution. This is illustrated in Figure 5 (top left) that shows the logarithm of with , using Corollary 5.5. The red line is a fitted curve to for the even states: , . The errors between true and predicted values are numerically smaller than 0.1 for all even states. Hence, the measure appears to grow super-exponentially fast. The function for the odd states grows at a comparable rate as that for the even states, but not with the same regularity.

Additionally, we computed the difference in for different values of , showing again a distinction between odd and even states, see Figure 5 (top right).

We used the linear approximation scheme to estimate the generating terms (which we know are not uniquely given in this case). Aslo here, an alternating pattern emerges with even indices producing the generator (), while odd indices producing the generator (). For each , a unique solution is found. Computing the corresponding yields another approximation to , namely , which is slightly larger than the previous approximation, . By nature of the latter estimate, the first coordinate is increasing in , while the second is decreasing in , hence the latter smaller interval is closer to the true interval , than the former. Figure 5 (bottom left) also shows the estimated generating terms for different values of , providing a band for and for which stationary measures exist, in agreement with Lemma 6.7.

Finally, we computed the ratio of to for different values of , and observe that there appears to be one behavior for odd states and one for even. While one cannot infer the large state behavior of the ratios in Figure 5 (bottom right) from the figure, it is excluded by non-uniqueness of the measures, that they both converges to zero, see Lemma 6.7.

Example 9.6.

Consider the SRN with non-mass-action kinetics:

with transition rates given by:

For this SRN, , , , and . Hence, the conditions of Proposition 7.3 are satisfied. The underlying CTMC is from [24], where it is shown that for is a signed invariant measure. This measure has generator . The space of signed invariant measures is dimensional, and a second linearly independent signed invariant measure has generator . On the other hand, by the Foster-Lyapunov criterion [23], the process is positive recurrent, and hence admits a stationary distribution. Numerical computations show that the stationary distribution is concentrated on the first few states . The uniqueness of the stationary distribution is also confirmed by Corollary 5.5 in that by a simple calculation.

Appendix A Appendix

Lemma A.1.

Assume (A1)-(A3). The following hold:

-

i)

, for , and for .

-

ii)

for and for .

-

iii)

for and . Generally, , .

-

iv)

for and . Generally, , .

-

v)

If , then , and similarly, if , then for and .

-

vi)

for and .

-

vii)

for and .

-

viii)

If , then , and similarly, if , then for and .

Proof.

i) Since , we have from (4.7),

For , we have and if . Hence, . For , we have and if . Hence, . ii) Since , then for , we have , see (4.6). Likewise, for . iii) and iv) The sign follows similarly to the proof of ii). Using i), the conditions on ensure and , respectively, yielding the conclusions. v) It follows from (A2). vi)-viii) Similar to iii)-iv) using (4.5) and (4.7). ∎

For a matrix , the -th column, , is weakly diagonally dominant (WDD) if and strictly diagonally dominant (SDD) if . In particular, a matrix is WDD if all columns are WDD. A WDD matrix is weakly chain diagonally dominant (WCDD) if for each WDD column, say , which is not SDD, there exists an SDD column such that there is a directed path from vertex to vertex in the associated digraph. Every WCDD matrix is non-singular [5].

Lemma A.2.

Assume (A1)-(A3). Then, the row echelon form of , as defined in (4.8), exists.

Proof.

Recall that

Note the following: if , then and hence . Hence, we might replace by in .

Define for . Then the row echelon form restricted to its first columns is invertible, that is, if

is invertible. Multiplying the above matrix by the invertible diagonal matrix

on the left side and its inverse on the right side gives a column diagonally dominant matrix

Note that . Furthermore, by () the following property holds: implies for any , or by contraposition, implies for any . Hence,

and therefore,

Consequently, the -th column sum of is positive, implying is WDD matrix with SDD column .

By Lemma A.3, is invertible, and hence the row reduced echelon form exists. ∎

Lemma A.3.

Let and assume is an matrix, such that

where for , , , and implies for any , . Then is WCDD, and thus non-singular.

Proof.

Number rows and columns from to . If , then the statement is trivial. Hence assume .

Fact 1: If column sums to zero, then column sums to zero. Indeed, that column sums to zero is equivalent to , which by the property of , implies that

| (A.1) |

Hence also and column sums to zero. Consequently, if column is WDD, but not SDD, then all columns are WDD, but not SDD.

Fact 2: If column sums to zero, then from (A.1) it holds that . Inductively, using in addition Fact 1, for , corresponding to a lower left triangular corner of size . ∎

Acknowledgements

The second author was supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation (Denmark), grant NNF19OC0058354. The third author was supported by TUM University Foundation, the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Simons Foundation, and a start-up funding from the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa.

The work was initiated when all authors were working at the University of Copenhagen. We are grateful to the AE and two anonymous reviewers whose comments and suggestions improved the presentation of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- [1] Abramowitz, M. and Stegun, I.A. Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables, volume 55 of Applied Mathematics Series. National Bureau of Standards, 1972.

- [2] Anderson, D.F, Craciun, G. and Kurtz, T.G. Product-form stationary distributions for deficiency zero chemical reaction networks. Bulletin Mathematical Biology, 72:1947–1970, 2010.

- [3] Anderson, D.F. and Kurtz, T.G. Stochastic Analysis of Biochemical Systems, volume 1.2 of Mathematical Biosciences Institute Lecture Series. Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, 2015.

- [4] Anderson, W.J. Continuous-Time Markov Chains: An Applications–Oriented Approach. Springer Series in Statistics: Probability and its Applications. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1991.

- [5] Azimzadeh, P. A fast and stable test to check if a weakly diagonally dominant matrix is a nonsingular M-matrix. Mathematics of Computation, 88(316):783–800, 2019.

- [6] Boyd, S.P. and Vandenberghe, L. Convex Optimization. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- [7] Derman, C. Some contributions to the theory of denumerable Markov chains. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 79(2):541–555, 1955.

- [8] Douc, R., Moulines, E., Priouret, P. and Soulier, P. Markov Chains. Springer Series in Operations Research and Financial Engineering. Springer 2018.

- [9] Erban, R., Chapman, S.J. and Maini, P.K. A practical guide to stochastic simulations of reaction-diffusion processes. arXiv:0704.1908, 2017.

- [10] Ethier, S.N. and Kurtz, T.G. Markov Processes. Wiley Series in Probability and Mathematical Statistics. Wiley, 1986.

- [11] Falk, J., Mendler, M. and Drossel, B. A minimal model of burst-noise induced bistability. PloS one, 12(4):e0176410, 2017.

- [12] Gillespie, D.T. Exact stochastic simulation of coupled chemical reactions. Journal of Physical Chemistry, 81:2340–2361, 1977.

- [13] Gillespie, D.T. A rigorous derivation of the chemical master equation. Physica A: Stat. Mech. Appl., 188:404–425, 1992.

- [14] Gupta, A., Mikelson, J. and Khammash, M. A finite state projection algorithm for the stationary solution of the chemical master equation. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 147(15):154101, 2017.

- [15] Harris, T.E. Transient Markov chains with stationary measures. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, 8(5):937–942, 1957.

- [16] Jahnke, T. and Huisinga, W. Solving the chemical master equation for onomolecular reaction systems analytically. J. Math. Biol., 54:1–26, 2007.

- [17] Kelly, F.P. Reversibility and Stochastic Networks. Applied Stochastic Methods Series. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- [18] Khinchin, A. Ya. Continued Fractions. Dover Publications, revised edition, 1997.

- [19] Kittappa, R. K. A representation of the solution of the nth order linear difference equation with variable coefficients. Linear algebra and its applications, 193:211–222, 1993.

- [20] Kuntz, J., Thomas, P. , Stan, Guy-Bart and Barahona, M. Stationary distributions of continuous-time Markov chains: a review of theory and truncation-based approximations. SIAM Review, 63(1):3–64, 2021.

- [21] López-Caamal,F. and Marquez-Lago,T. T. Exact probability distributions of selected species in stochastic chemical reaction networks. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 76:2334–2361, 2014.

- [22] Marrero, J.A. and Tomeo, V. On compact representations for the solutions of linear difference equations with variable coefficients. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics, 318:411–421, 2017.

- [23] Meyn, S. P. and Tweedie, R. L. Markov Chains and Stochastic Stability. Cambridge University Press, 2nd edition, 2009.

- [24] Miller Jr, R. G. Stationary equations in continuous-time markov chains. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 109(1):35–44, 1963.

- [25] Norris,J.R. Markov Chains. Cambridge Series in Statistical and Probabilistic Mathematics. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- [26] Pastor-Satorras, R., Castellano, C., Van Mieghem, P. and Vespignani, A. Epidemic processes in complex networks. Rev. Mod. Phys., 87:925–979, 2015.

- [27] Shahrezaei, V. and Swain, P.S. Analytical distributions for stochastic gene expression. PNAS, 105:17256–17261, 2008.

- [28] Whittle, P. Systems in Stochastic Equilibrium. Wiley Series in Probability and Mathematical Statistics: Applied Probability and Statistics. John Wiley Sons, Inc., Chichester, 1986.

- [29] Xu, C., Hansen, M.C. and Wiuf, C. Structural classification of continuous time Markov chains with applications. Stochastics, 94:1003–1030, 2022.

- [30] Xu, C, Hansen, M.C. and Wiuf, C. Full classification of dynamics for one-dimensional continuous-time Markov chains with polynomial transition rates. Advances in Applied Probability, 55:321–355, 2023.

- [31] Xu, C, Hansen, M.C. and Wiuf, C. The asymptotic tails of limit distributions of continuous time Markov chains. Advances in Applied Probability, pages 1–42, 2023. doi:10.1017/apr.2023.42.