The chromospheric emission of solar-type stars in the young open clusters IC 2391 and IC 2602

Abstract

In this paper we present chromospheric emission levels of the solar-type stars in the young open clusters IC 2391 and IC 2602. High resolution spectroscopic data were obtained for over 50 F, G, and K stars from these clusters over several observing campaigns using the University College London Echelle Spectrograph on the 3.9-m Anglo-Australian Telescope. Unlike older clusters, the majority (28/52) of the solar-type stars in the two clusters are rapid-rotators (v sini 20 km s-1) with five of the stars being classified as ultra-rapid rotators (v sini 100 km s-1). The emission levels in the Calcium infrared triplet lines were then used as a measure of the chromospheric activity of the stars. When plotted against Rossby number (NR) the star’s chromospheric emission levels show a plateau in the emission for Log(NR) -1.1 indicating chromospheric saturation similar to the coronal saturation seen in previously observed X-ray emission from the same stars. However, unlike the coronal emission, the chromospheric emission of the stars show little evidence of a reduction in emission (i.e. supersaturation) for the ultra-rapid rotators in the clusters. Thus we believe that coronal supersaturation is not the result of an overall decrease in magnetic dynamo efficiency for ultra-rapid rotators.

keywords:

stars : rotation – stars : activity – stars : late-type – open clusters and associations: individual: IC 2391, IC 26021 Introduction

Solar-type stars of spectral types F, G and K arrive on the Zero-Age Main-Sequence (ZAMS) with a wide range of rotation rates, with many stars experiencing extremely rapid rotation (projected rotational velocities, v sini values, of 200 km s-1 or more). As angular momentum loss is believed to be dependent upon the rotation rate of a star through magnetic braking (e.g. Mestel & Spruit, 1987), such rapid rotators pose something of a problem as such stars should lose angular momentum much faster than they appear to do.

In order to account for these rapid rotators, dynamo theories of young solar-type stars have used dynamo saturation to slow the angular momentum loss of rapidly rotating stars (e.g. Irwin et al., 2007; Krishnamurthi et al., 1997; Barnes & Sofia, 1996). Below a critical rotation rate (the saturation velocity) the strength of a star’s magnetic dynamo is believed to be related to the star’s rotation rate. However, for stars rotating more rapidly than this it is theorised that the strength of the star’s magnetic dynamo is no longer dependent upon stellar rotation. As a result, the loss rate of angular momentum due to magnetic braking should not increase for solar-type stars with rotation rates greater than the saturation velocity.

The main observational evidence for dynamo saturation comes from the coronal X-ray emission (LX/Lbol, the star’s X-ray luminosity divided by the star’s bolometric luminosity) of young solar-type stars. When Log(LX/Lbol) is plotted against a measure of rotation rate, such as v sini, it is seen to initially increase with v sini until reaching a value of -3.0 when a plateau in emission level is observed for stars rotating more rapidly than v sini 20 km s-1. Such saturation is also seen in other activity indicators, such as H and Calcium emission (e.g. Soderblom et al., 1993) and this would appear to be consistent with the effect of dynamo saturation (Stauffer et al., 1997; Patten & Simon, 1996). However, the mechanism causing this saturation (or even if it is dynamo saturation) remains unknown.

Furthermore, for extremely rapid rotators (v sini 100 km s-1) the Log(LX/Lbol) value of these stars is then seen to drop below the saturation level of Log(LX/Lbol) = -3.0. This effect has been dubbed supersaturation by Prosser et al. (1996b).

Although the mechanisms causing both saturation and supersaturation are yet to be determined, some suggestions have been put forward, such as centrifugal stripping (Jardine & Unruh, 1999), and the complete filling of emitting regions (Stȩpień, Schmitt, & Voges, 2001). In order to better constrain both saturation and supersaturation observationally we need to determine what activity indicators show signs of these effects and measure the rotational velocities at which they occur (if at all).

The Calcium II emission of solar-type stars is an excellent diagnostic of chromospheric emission. Traditionally the Ca II H and K resonance lines at 3968Å and 3934Å have been used as chromospheric diagnostics and have been employed by Noyes et al. (1984) to look at the relationship between chromospheric emission and rotation rate for solar-type field stars. However observations of the Ca II H and K lines of faint stars can be difficult, due to often low stellar flux in the blue, and the relatively poor blue response of many CCD detectors. In contrast, there have been several studies (e.g. Chmielewski, 2000; James & Jeffries, 1997; Soderblom et al., 1993; Foing et al., 1989; Linsky et al., 1979) involving the use of the Calcium II infrared triplet (IRT) lines at 8498Å, 8542Å, and 8662Å, as chromospheric diagnostics. These lines are strong and their location in the red makes them more suitable for CCD observations. The strongest of the IRT lines, the 8542Å line, is relatively free from blends, and is largely uncontaminated by telluric lines, although Chmielewski (2000) shows that there is some small contamination in the wings of the 8542Å line, but not the core. The IRT lines have the same upper levels as the Ca II H and K resonance lines, but the lower levels are populated radiatively and are not collisionally controlled like the H and K lines (Mallik, 1997).

Chromospheric emission in the 8542Å line has previously been studied by Soderblom et al. (1993) (with the data also presented in Krishnamurthi et al., 1998) for young solar-type stars in the Pleiades cluster (age 130 20 Myrs; Barrado y Navascués, Stauffer, & Jayawardhana, 2004) and by James & Jeffries (1997) for the intermediate-age (220 Myrs) open cluster NGC 6475. Both results show chromospheric saturation occurring in the rapidly rotating stars with a saturation level in the 8542Å line of Log(R′8542) -4.2, where R′8542 is the flux in the 8542Å line divided by the star’s total bolometric luminosity, see § 5.4. However, due to the lack of ultra-rapid rotators in both these studies, there is no way of telling if the chromospheric emission shows evidence of supersaturation akin to that of the X-ray data. To further the results of Soderblom et al. (1993) and James & Jeffries (1997) this paper determines the chromospheric emission in the Calcium II infrared triplet lines for the solar-type stars in two younger clusters (IC 2391 and IC 2602) containing a higher proportion of rapidly rotating stars, including a number in the supersaturation regime.

2 The Open Clusters IC 2391 and IC 2602

The young open clusters IC 2391 and IC 2602 are both southern targets located near the galactic plane. Their HIPPARCOS distances of 145 pc (van Leeuwen, 1999) makes them among the closest young open clusters.

The age of the two clusters is given by Stauffer et al. (1997) as 30 5 Myrs. This age is based on both comparisons to evolutionary isochrones as well as the upper main-sequence turnoff age of the clusters. More recent work by Barrado y Navascués et al. (2004) has given an age for IC 2391 of 50 5 Myrs, based on the lithium depletion of fainter members of the cluster. This has yet to be done for IC 2602.

Given the ages of these two clusters the solar-type stars in IC 2391 and IC 2602 should be on, or in the last phase of evolving to, the ZAMS. At this age, the solar-type stars should not have undergone any significant magnetic braking and thus show a large range of rotational velocities including some stars with ultra-rapid rotation rates (v sini 100 km s-1) placing them within the supersaturation regime. This makes IC 2391 and IC 2602 ideal targets for the study of saturation and supersaturation.

Photometric work on IC 2602 was done by Braes (1962) and Whiteoak (1961), while similar observations were undertaken for IC 2391 by Hogg (1960), Buscombe (1965), Perry & Hill (1969), and Perry & Bond (1969) among others. In the past decade or so there has been renewed interest in these two clusters with ROSAT X-ray observations (Randich et al., 1995; Patten & Simon, 1996) along with XMM-Newton observations (Marino et al., 2005), as well as a spectroscopic survey by Stauffer et al. (1997) and rotation period determinations for a number of IC 2602 stars by Barnes et al. (1999) and for some IC 2391 stars by Patten & Simon (1996).

The metallicities of the two clusters has been determined by Randich et al. (2001) and D’Orazi & Randich (2009) to be close to solar with [Fe/H] = 0.00 0.01 and [Fe/H] = -0.01 0.02 for IC 2602 and IC 2391 respectively.

The designations of the cluster stars used throughout this paper are as follows. For IC 2391, VXR: designation from Patten & Simon (1996), H: from Hogg (1960), L: from Lyngȧ (1961), and SHJM: from Stauffer et al. (1989). For IC 2602, R: designation from Randich et al. (1995), B: from Braes (1962), and W: from Whiteoak (1961). Many of the stars have multiple designations and where possible the designations from Patten & Simon (1996) and Randich et al. (1995) have been used for the stars in IC 2391 and IC 2602 respectively.

For stars in IC 2391 the quoted photometry is from Patten & Simon (1996), Lyngȧ (1961), Hogg (1960), and Stauffer et al. (1989). The rotational periods are from Patten & Simon (1996) and the previous v sini values are from Stauffer et al. (1989) and Stauffer et al. (1997). For IC 2602 the photometry is taken from Prosser, Randich & Stauffer (1996a), Randich et al. (1995), and Barnes et al. (1999). The rotational periods are from Barnes et al. (1999) and the previous v sini values are from Stauffer et al. (1997).

Because of the similarities between the two clusters, in age, distance, metallicity, etc., and the relative paucity of stars in the clusters (compared to say the Pleiades), IC 2391 and IC 2602 are treated as one cluster. We present the results from both clusters together, although stars from each cluster are represented by different symbols.

Most of the information, such as names, membership, positions, colours, etc., for the stars in the two clusters can be found in the WEBDA database111WEBDA database - http://www.univie.ac.at/webda/.

3 Selection of Targets

Potential members of IC 2602 were identified by Randich et al. (1995) from ROSAT X-ray data, with a number of active low-mass candidate members of the cluster found. A similar approach was taken by Patten & Simon (1996) for the members of IC 2391. Prosser et al. (1996b) and Stauffer et al. (1997) then carried out photometric and spectroscopic confirmation of membership studies (along with v sini measurements), and a list of active low-mass members of the clusters was produced. The listing that Stauffer et al. (1997) gives for IC 2391 is not as complete as that given by Patten & Simon (1996) so we have added some of the Patten & Simon (1996) stars to the list of potential members. This list is still not a complete census of the solar-type members in the two clusters, because, as Stauffer et al. (1997) points out, in neither cluster does the ROSAT survey used to determine membership cover the entire area of the sky over which cluster members are likely to occur. Stauffer et al. (1997) argue that although the list is incomplete it should not be overly biased (towards active stars) by the selection process (using X-ray emission to determine membership) for at least the G dwarfs in the two clusters. For the K dwarfs they believe that any bias should not be a large effect. A more comprehensive explanation of their selection process along with estimates of the completeness of the sample is given in Stauffer et al. (1997).

To the Stauffer et al. (1997) list (along with additional stars from Patten & Simon (1996)), we have added further stars from the Braes (1962) and Whiteoak (1961) photometric studies of IC 2602, as well as some IC 2391 stars from Hogg (1960), Lyngȧ (1961), and Stauffer et al. (1989), again not observed by Stauffer et al. (1997). The IC 2602 photometric studies by Braes (1962) and Whiteoak (1961) only went as deep as V 11, meaning that stars added to the list from these studies were predominantly late-F/early-G stars.

With the possible exception of the above mentioned additional stars, we believe that most of the stars in our target list should be cluster members. However a further membership determination was made based on radial velocity and Lithium line strength, see § 5.2.

For this study as many of the solar-type stars in our target list were observed as possible in the time available, without biasing the observations through colour selection effects. This was achieved with observations of all of the selected stars in both IC 2391 and IC 2602 with 0.4 (V-IC)0 1.4, corresponding to early-F to mid-K stars. Due to time constraints and the wish not to bias the observations by only obtaining data on a few lower-mass stars, all stars with (V-IC)0 1.4 were excluded. Thus the observations should constitute a relatively unbiased sample of solar-type stars from early-F through to mid-K. In IC 2391 32 stars were observed from the target list, while in IC 2602 51 stars were observed from the target list.

A list of the stars with 0.4 (V-IC)0 1.4 observed in IC 2391 and IC 2602 are given in Tables 1 and 2 respectively.

Landscape Table 1 to go here.

Landscape Table 2 to go here.

4 Observations

The spectroscopic data for this project were collected over 3 separate observing campaigns at the 3.9-m Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT) located at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales, Australia. The 3 observing runs consisted of 3, 3, and 2 nights in March 2000, January 2001, and February 2001, respectively.

The spectroscopic data were obtained using the University College London Echelle Spectrograph (UCLES). The detector used for the first two runs (March 2000 and January 2001) was the Deep Depletion MITLL3 CCD with 2048 4096 15 m square pixels. This chip was chosen for its excellent red response and low fringing. For the third run (February 2001), the chip used was the lumogen coated MITLL2A CCD, again with 15 m square pixels. This chip does not have the improved red response of the MITLL3, however the MITLL3 chip was unavailable at the time.

Since both of the chips are larger than the unvignetted field of the UCLES camera, a smaller window format (2048 2896 pixels) was used to reduce read out time. Using the 31.6 gr/mm grating, 57 orders (#55 to #111) could be fitted onto the detector window. Only 49 (#63 to #111) were reduced (the remaining orders had little or no signal in them) giving full wavelength coverage from 5000Å to 9000Å. While the actual wavelength range varied slightly from run to run, this variation was minimal.

With a slit-width of 1 arcsecond the spectral resolution varied from 44,000 to 46,000 during the 3 runs, giving a velocity resolution of 6.8 km s-1 to 6.5 km s-1.

Several exposures were taken consecutively for each star and added together to improve the signal-to-noise and also in case cosmic rays affected the IRT lines. The raw frames were then reduced and converted into wavelength calibrated spectra using the ESpRIT (Echelle Spectra Reduction: an Interactive Tool) optimal extraction routines of Donati et al. (1997).

5 Results

5.1 Measuring Rotational and Radial Velocities

The major part of this study involves investigating the relationship between chromospheric activity and the rotation rates of solar-type stars in IC 2391 and IC 2602. Although many of the stars in the observation list have previous v sini values measured by Stauffer et al. (1989, 1997), a number of stars still had none. To have a consistent v sini determination for the entire observation list, it was decided to re-determine the values of v sini of all the observed stars. In order to do this the Least-Squares Deconvolution (LSD) profiles for the stars were extracted from the spectrum of each star using the routines of Donati et al. (1997).

An LSD profile can be considered as the resultant sum of the several thousand photospheric lines contained within each Echelle spectrum, yielding an “average” single high S/N profile (see Donati et al. 1997 for more details). The resultant gain in S/N from this process was 10 times that of the S/N in the 8542Å line, depending on the spectral type of the star observed. The LSD profiles of three low activity stars of differing spectral types were also produced from the observations. These stars were HD 16673, Cen A, and Cen B, with spectral types of F6V, G2V and K1V respectively.

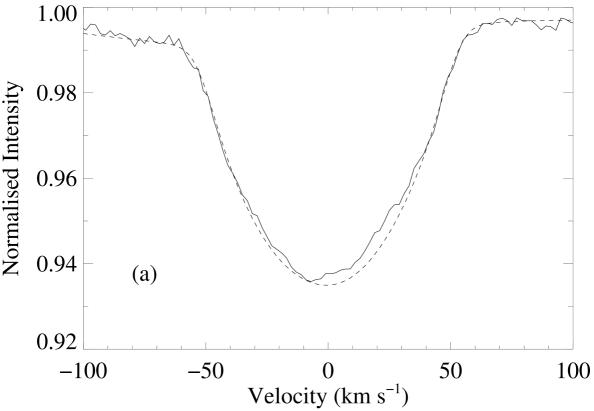

Based on the colour of the target star an inactive star of similar spectral type was then rotationally broadened to match the target star’s LSD profile. Given the high S/N of the LSD profiles (from 300 to 900) the fit to the rotationally broadened profile could usually be found to within 1 km s-1. This error is based on internal consistency within the method by observing the same star over several epochs. The v sini values of Cen A and Cen B are given by Valenti & Fischer (2005) as 2.3 km s-1 and 0.9 km s-1 respectively. Given the instrumental resolution of the observations (6.5 to 6.8 km s-1) we estimate that the lower v sini limit we could determine for our stars was 7 km s-1 when using Cen A or B as a template. This is not the case for HD 16673. The v sini value for this star is given by Nordström et al. (2004) as 8 km s-1. This means that for those stars using HD 16673 as a template the lower v sini limit was 11 km s-1. However, no slowly-rotating stars determined to be cluster members used HD 16673 as a temple star. The LSD profile of one of the target stars and the fit to a rotationally broadened low activity star is given in Figure 1(a). A list of the v sini values for the observed stars, determined using this LSD method (along with comparisons to previous measurements) is given in Tables 1 and 2.

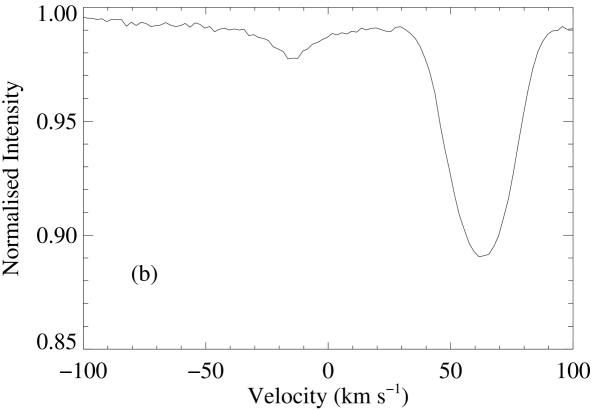

Using those single stars from Tables 1 and 2 that have previously had their v sini values determined, the relationship between the v sini measured here using the LSD profiles and previous measurements (from Stauffer et al., 1989, 1997) was determined. This relationship is shown in Figure 2 and using a linear fit was found to be (with 1 errors):

| (1) |

Along with being a useful technique for the measurement of rotational broadening, the high S/N of the LSD profile also makes it a good way to determine if a star is a double-lined spectroscopic binary. Tables 1 and 2 also note those stars suspected of being double-lined binaries based on their LSD profiles. The LSD profile of one of these binaries is given as an example in Figure 1(b).

All single members of a cluster are expected to have a similar radial velocity. During the fitting of the LSD profiles of the inactive stars to the target stars in IC 2391 and IC 2602 we have also determined the radial velocity of our target stars. These are heliocentric radial velocities which have then been shifted to match the centroid of the LSD profile of the telluric lines in each spectrum to account for any changes in temperature or pressure experienced by the spectrograph during the coarse of the observations. This should give a zero point error of 0.3 km s-1 for both the target and inactive stars. Thus given an estimated error of 1 km s-1 for the method we estimate that the radial velocity measurements are accurate to 1.5 km s-1. The radial velocities of the observed stars measured through this technique are again given in Tables 1 and 2. The mean and standard deviation of the radial velocities for the two clusters (measured from those stars given a M membership classification, see § 5.2) was found to be 15.9 0.7 km s-1 and 17.4 1.0 km s-1 for IC 2391 and IC 2602 respectively.

5.2 Cluster Membership

As mentioned in § 3, we believe that most of the stars in out target list should in fact be cluster members, based on previous selections. However, we have made a further determination of the cluster membership based on the strength of the star’s Lithium 6708Å line in our observations and our determination of the radial velocity of the star. The strength of the Lithium line was only determined approximately with respect to the strength of the nearby Ca 6717Å line, and given as Strong, Weak, or None. A more detailed study of the Lithium in the two clusters has been undertaken by Randich et al. (1997), Randich (2001), and Randich et al. (2001).

Most of the single stars in Tables 1 and 2 with strong Lithium appear to have radial velocities around 16 km s-1 for IC 2391 and 17 km s-1 for IC 2602. Thus in order to qualify as a member of the cluster (M classification) stars have to be single (i.e. no evidence of a binary in their LSD profile), have strong Lithium, and have a radial velocity of 16 2 km s-1 for IC 2391 stars and 17 2 km s-1 for IC 2602. Stars which are classified as probable members (denoted by a ? classification) have a strong Lithium feature and are either binary or if single have a radial velocity of 16 9 km s-1 for IC 2391 stars or 17 9 km s-1 for IC 2602 stars. All other stars are classified as non-members (N classification). This membership is given in Tables 1 and 2. In our analysis of the chromospheric emission of the stars (§ 5.4) we have included all single stars with either M or ? classifications.

Since these observations there have been other determinations of cluster membership, such as that by Platais et al. (2007) for IC 2391. The membership list of Platais et al. (2007) contains a number of new IC 2391 members not contained in our list, however this was published too late for our study. The Platais et al. (2007) list also has membership determinations for the stars in our list. The determination of membership agrees reasonably well with our list. In addition, Platais et al. (2007) list several IC 2391 stars as single-lined spectroscopic binaries that we treat as single, however, the contribution from the secondary to the chromospheric emission should be minimal so we have included them. Table 3 gives a list of differences between our designations and that of Platais et al. (2007). Stauffer et al. (1997) list the star R80 (IC 2602) as a possible non-member. Based on our measurement of its radial velocity and Lithium we feel it is consistent with membership, and hence we have included it as such.

| Star | Our | Platais et al. (2007) |

|---|---|---|

| Name | designation | designation |

| L32 | M | M + B |

| VXR02B | N | M |

| VXR05 | ? + B | M + B |

| VXR07 | ? | M + B |

| VXR08 | N | M + B |

| VXR11 | ? + B | M + B |

| VXR30 | N | M + B |

| VXR31 | ? | N |

| VXR35A | M | ? |

| VXR44 | ? | M + B |

| VXR45A | M | ? |

| VXR50A | ? | N |

| VXR52 | M | M + B |

| VXR62A | ? | M |

| VXR67A | ? | M + B |

| VXR70 | ? | M |

| VXR78 | ? | N |

5.3 Stellar Parameters

The effective temperatures of the stars given in Tables 1 and 2 were calculated from (V-IC)0 colours and the colour vs. Teff relationships of Bessell, Castelli & Plez (1998). If no (V-IC)0 measurement was available for the star then (B-V)0 was used. The (V-IC) and (B-V) values were converted to unreddened values by using the reddening parameters for the clusters. E(B-V) = 0.04 for IC 2602 from Braes (1961) and E(B-V) = 0.006 (rounded to 0.01) for IC 2391 from Patten & Simon (1996). The E(V-IC) values for the two clusters were found by multiplying the E(B-V) values by 1.25 as given in Pinsonneault et al. (1998), thus giving values of E(V-IC) = 0.05 and E(V-IC) = 0.0075 (rounded to 0.01) for IC 2602 and IC 2391 respectively.

The luminosities of the target stars were calculated from:

| (2) |

where 4.74 is the Mbol for the Sun (Bessell et al., 1998) and BCI is the bolometric correction in the I band calculated using Bessel & Stringfellow (1993). The distance moduli used for the clusters were 5.82 and 5.81 for IC 2391 and IC 2602 respectively taken from the HIPPARCOS distances of van Leeuwen (1999). If no (V-IC)0 value was available then:

| (3) |

was used instead, with the BCV calculated from Bessell et al. (1998).

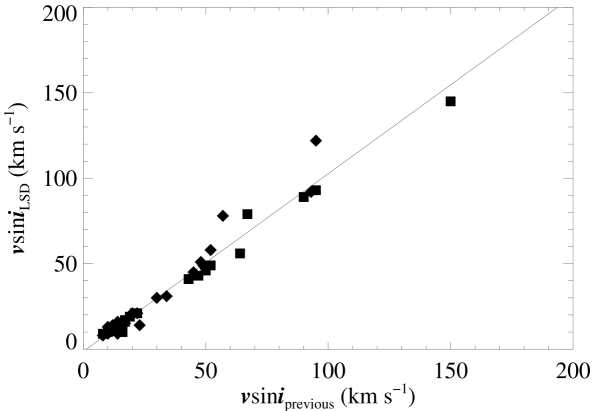

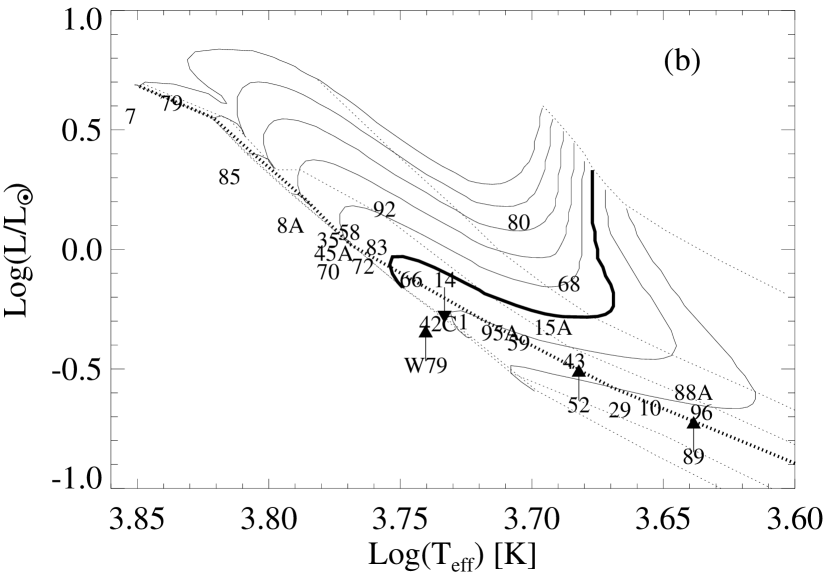

Masses of the observed stars were estimated from D’Antona & Mazzitelli (1997) isochrones to the nearest 0.1 solar mass (see Figure 3). Radii were then calculated from Equation 2 and:

| (4) |

5.4 Measuring Chromospheric Emission

Only those stars deemed to be probable cluster members and probably single (or at least single-lined spectroscopic binaries) had their chromospheric emission measured. Single stars were used because of the difficulty in determining the relative contributions to the emission for binary components. Before any chromospheric analysis was carried out on the spectra, telluric lines in the wings of the three IRT lines were first removed from both the target and inactive star spectra.

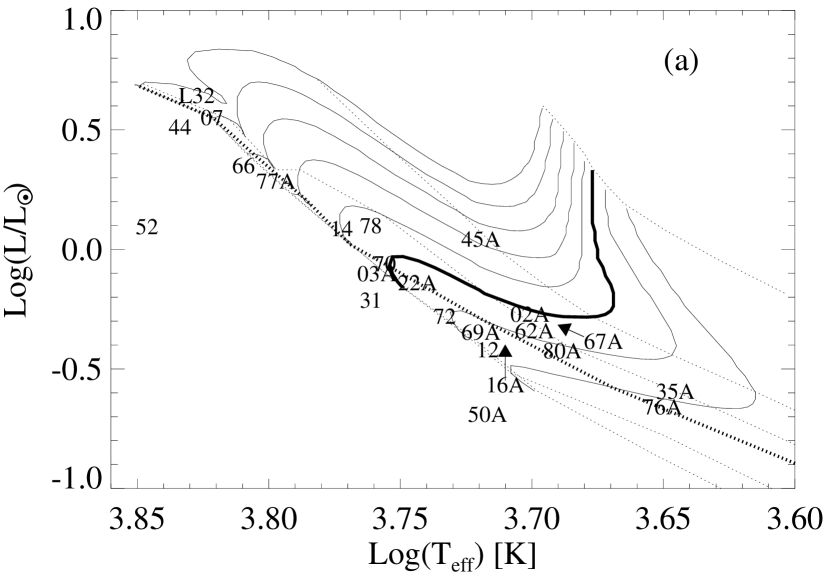

As mentioned previously there have been several studies involving the use of the IRT lines as chromospheric diagnostics, however the studies have adopted slightly different methods of determining the chromospheric activity of the stars, employing various bandwidths to measure chromospheric emission. The method we have adopted is that used by Soderblom et al. (1993) in their measurement of the 8542Å line of solar-type stars in the Pleiades, whereby the chromospheric emission is calculated from the emission profile of the star.

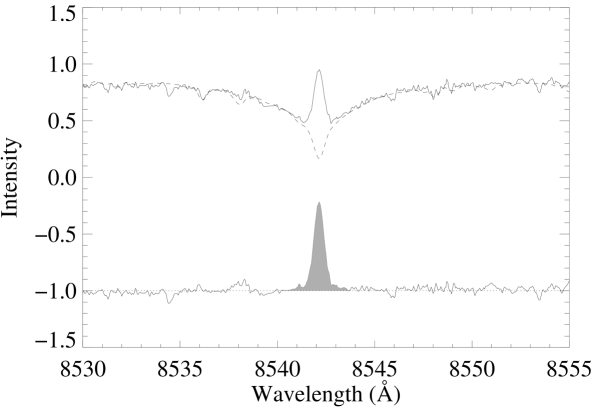

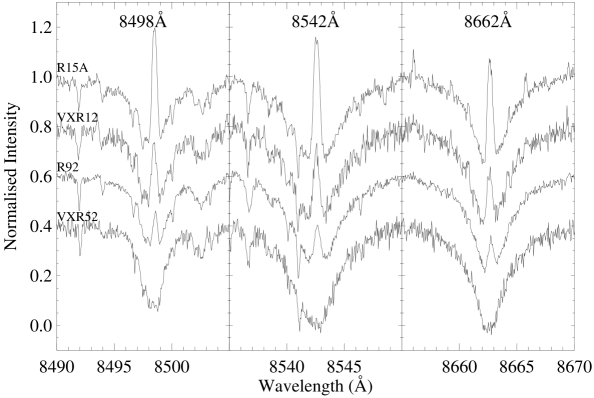

For all three of the IRT lines the spectrum of an inactive star of similar spectral type was rotationally broadened to match that of the target star. The inactive star’s spectrum was then shifted to match the radial velocity of the target star and was fitted to the target star’s spectrum by matching the wings of the IRT line being examined, as the chromospheric emission should be limited to the core of the lines. The spectrum of the inactive star was then subtracted from the target star to produce an emission profile. To measure the chromospheric emission from the IRT lines, the area under the emission profile was calculated to produce an emission equivalent width. The process is outlined in Figure 4 for the 8542Å line while Figure 5 gives examples of the emission in the IRT lines for a sample of stars of differing activity levels.

By subtracting the IRT line of an inactive star (taken with the same instrumental setup) from that of our target stars, the photospheric contribution to the line is removed, and the resultant emission profile contains the chromospheric emission of the star. This method also removes a small amount of chromospheric emission, as no star is completely inactive. The inactive stars chosen for this project were the same as those used to determine the v sini of the target stars, namely HD16673 (F6V), Cen A (G2V), and Cen B (K1V). These stars have near solar-metallicity (HD 16773: [Fe/H] = -0.11, Cen A/B: [Fe/H] = 0.12 according to Nordström et al. (2004)). Although these inactive stars are not zero-age main-sequence stars (it is virtually impossible to get an inactive zero-age main-sequence star for comparison) the differences in surface gravity between these stars and those of IC 2391/2602 should have minimal effect on the chromospheric measurements, particularly for rapidly-rotating stars where rotational broadening will dominate the line profile.

To measure the chromospheric emission of the IRT lines we have determined the chromospheric emission ratio (R′IRT) for each of the IRT lines. This gives the fraction of each star’s bolometric luminosity that is emitted from the chromosphere in the IRT line. This is analogous to the chromospheric emission ratio R′HK derived from Ca II H and K observations described by Noyes et al. (1984), where the prime signifies that the photospheric emission has been removed. R′8542, the chromospheric emission ratio in the 8542Å line, has been used previously by Soderblom et al. (1993) and James & Jeffries (1997).

To calculate R′IRT for each of the lines, the emission equivalent widths were first converted into the surface flux emitted by the IRT lines (F′IRT). Using the effective temperatures of the target stars from Tables 1 and 2, the surface flux per Ångstrom was calculated for each star by interpolating between model atmospheres from Kurucz (1993). This was then multiplied by the star’s Emission Equivalent Width to give the surface flux in each of the IRT lines (F′IRT). In order to remove the dependence of the surface flux upon the star’s colour, the chromospheric emission ratio in the IRT lines (R′IRT) was then calculated for each star. This is defined as the ratio of the surface flux in the IRT line to the star’s total bolometric emission.

| (5) |

with F′IRT in W m-2 and Teff in K.

The chromospheric emission ratios, emission equivalent widths, and surface fluxes, for single members of the two clusters are given in Tables 4 and 5.

Landscape Table 4 to go here.

Landscape Table 5 to go here.

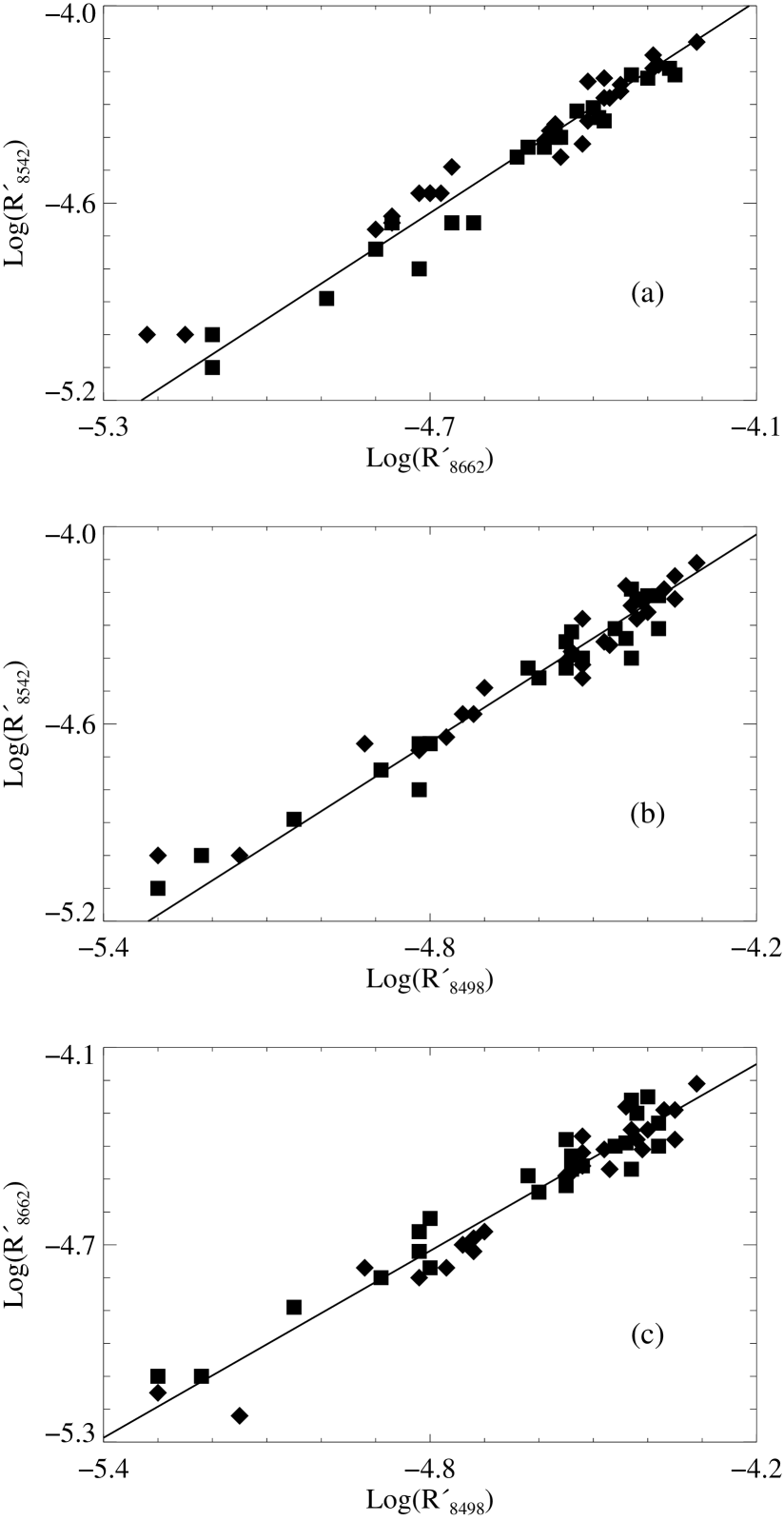

5.4.1 Errors in Chromospheric Emission Measures

Possible errors in the measurement of the chromospheric emission come from a number of sources; errors in the measurement of the emission equivalent width, errors in determination of effective temperature, a mismatching of the spectral-type of the inactive stars to that of the target stars, and lastly the intrinsic variability of the chromospheric emission of the star’s themselves. Errors in effective temperature determinations of 100 K are likely to produce errors of less than 10% in the measurement of the chromospheric emission ratios, while Soderblom et al. (1993) found no perceptible differences in the infrared triplet lines of the inactive field stars they studied which cover a similar colour range to our data, thus a mismatch of the spectral-type of the inactive template star should have minimal effect of the results. Thus the most likely sources of error to affect our results are errors in the measuring of the emission equivalent width and the intrinsic variability of the stars themselves. Although Tables 1 and 2 show that multiple observations were taken of each star these were mostly taken consecutively, so unfortunately cannot be used to determine any measure of the intrinsic variability of the stars. In order to determine the error in the measurement of the emission equivalent width on the chromospheric emission ratios of these stars we have plotted a comparison of the chromospheric emission ratios for the three infrared triplet lines (see Figure 6). We have then fitted simple linear fits to the data and determined the following relationships:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

Looking at the scatter around these lines of best fit it can be seen that the error in Log(R′8542) when plotted against Log(R′8662), i.e. comparing the two strongest lines, is smaller for more active stars than for inactive stars and varies from 0.1 for active stars up to 0.2 for the inactive stars in the sample. This error is actually a cumulative measure of the error in both of the lines plotted and thus the measurement error in each individual line is most likely less than this. However, taking into account possible errors in the effective temperature we believe that 0.1 is a reasonable estimate of the error in our Log(R′IRT) values. An error of 0.1 in Log(R′IRT) appears to hold even for the ultra-rapid rotators in the clusters, however the fitting of the inactive star spectrum is difficult due to the rotationally broadened width of the chromospheric lines in these stars, and thus based on fitting errors we believe that the error in Log(R′IRT) for the ultra-rapid rotators may be slightly higher than this at 0.15.

5.5 Activity versus Rotation

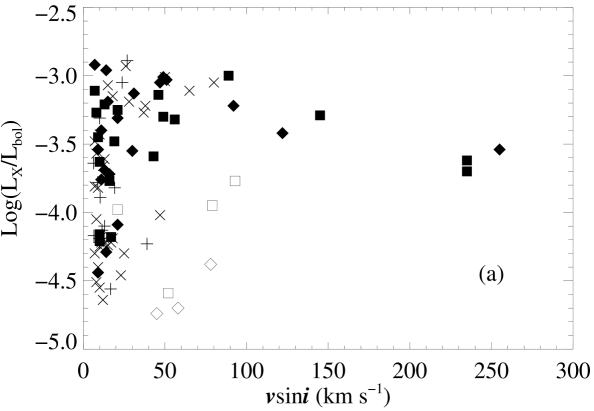

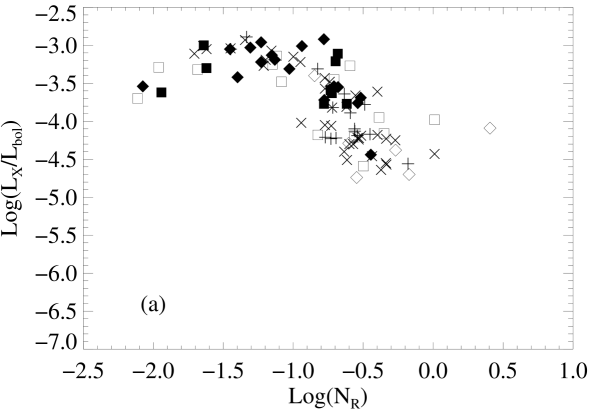

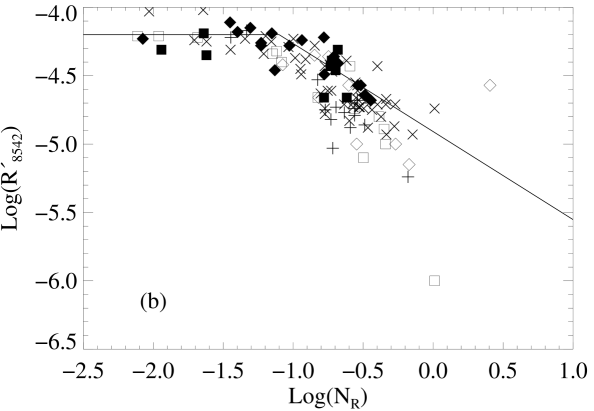

As mentioned previously the coronal X-ray emission of young active solar-type stars show a saturation of activity for rapid rotation, with the emission showing a further supersaturation effect for ultra-rapid rotation. Figure 7 plots the Log of the coronal X-ray emission (divided by the star’s bolometric luminosity) and the Log of the chromospheric emission ratio for the strongest of the IRT lines, 8542Å, against v sini for the observed single stars in IC 2391 and IC 2602. The coronal X-ray data for IC 2391 and IC 2602 are taken from Patten & Simon (1996) and Stauffer et al. (1997) and were not taken simultaneously with the choromspheric results presented here. This means that variability and flaring may influence the scatter in these plots (and those in Figures 9 and 11). The v sini values used in Figure 7 are those measured in this study. The coronal data for the Pleiades were taken from Stauffer et al. (1994) and Micela et al. (1999) while the chromospheric data were taken from Soderblom et al. (1993). For NGC 6475 both the coronal and chromospheric data were taken from James & Jeffries (1997).

Note: For the three stars in Tables 1 and 2 that have values of v sini 7 km s-1 and are plotted in this section (VXR76A, R1, and R15A), their v sini values have been assumed to be 7 km s-1 for plotting purposes and the calculation of Rossby number if the rotational period is unknown.

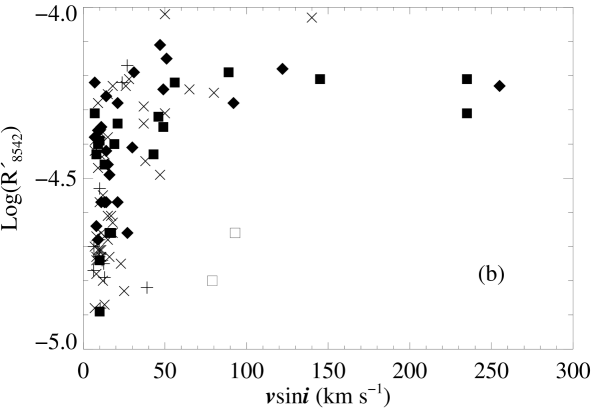

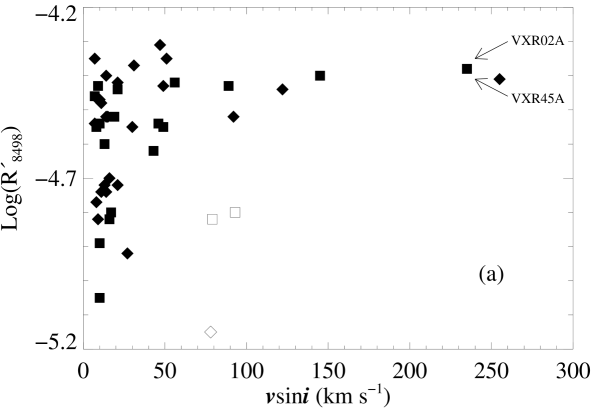

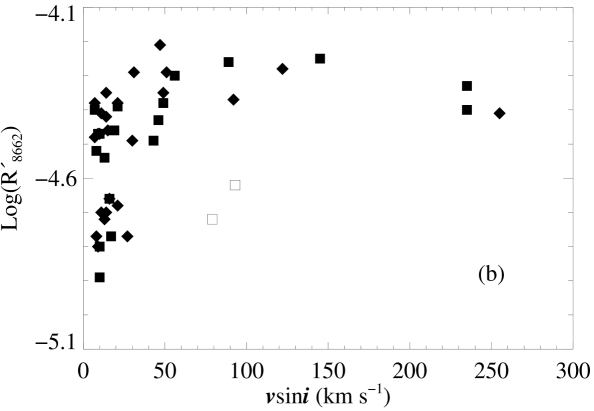

The activity levels of the target stars have also been determined for the two weaker IRT lines (8498Å and 8662Å). The Log of the chromospheric emission ratio versus v sini for these two lines is given in Figure 8.

Both the chromospheric (in all three of the IRT lines) and the coronal emission show a saturation for rapid rotators. The coronal emission shows supersaturation for ultra-rapid rotators. However, the chromospheric emission shows little (if any) decrease for the ultra-rapid rotators (although the 8662Å line appears to show a possible slight decrease).

In order to remove both the uncertainty in the inclination angle as well as any mass dependency in the velocity at which saturation starts (the saturation velocity), Noyes et al. (1984) plotted activity against a value called the Rossby number (NR) as a measure of a star’s rotation rate. Rossby number is defined as the star’s rotational period divided by a measure of the star’s convective turnover timescale (c). Noyes et al. (1984) determined c based on the (B-V) colour of the target star.

A number of the stars in Tables 1 and 2 have period determinations. The Rossby number for these stars has been calculated using c from Noyes et al. (1984) Equation 4:

| (9) |

where = 1 (B-V)0 and c is in days. There have been later calculations of the convective turnover timescale, such as those by Kim & Demarque (1996) used by Krishnamurthi et al. (1998), which are more suited to pre-main sequence stars. The Kim & Demarque (1996) values for c do vary from those calculated using the Noyes et al. (1984) formula above. If the Kim & Demarque (1996) values are used, Figure 9 remains fundamentally unchanged except that the Rossby numbers are all shifted to lower values and the saturation occurs at Log(NR) -1.5 rather than the Log(NR) -1.0 shown in Figure 9. We have decided to use the Noyes et al. (1984) values as many of the previous observations of saturation and supersaturation have used them (e.g. Soderblom et al., 1993; Patten & Simon, 1996; Stauffer et al., 1997).

For those stars in Tables 1 and 2 that do not have measured rotational periods, we have used the method of Soderblom et al. (1993) to estimate the Rossby number from the v sini of the star. The equation used is:

| (10) |

where R is the stellar radius (in km), v sini is in km s-1, and c (in seconds) is calculated from Equation 9. Assuming that stellar inclination angles are randomly distributed, then sin should be 0.785, so we have multiplied Equation 10 by this amount. We have also done this for the calculated Rossby numbers for the Pleiades and NGC 6475 which we have plotted.

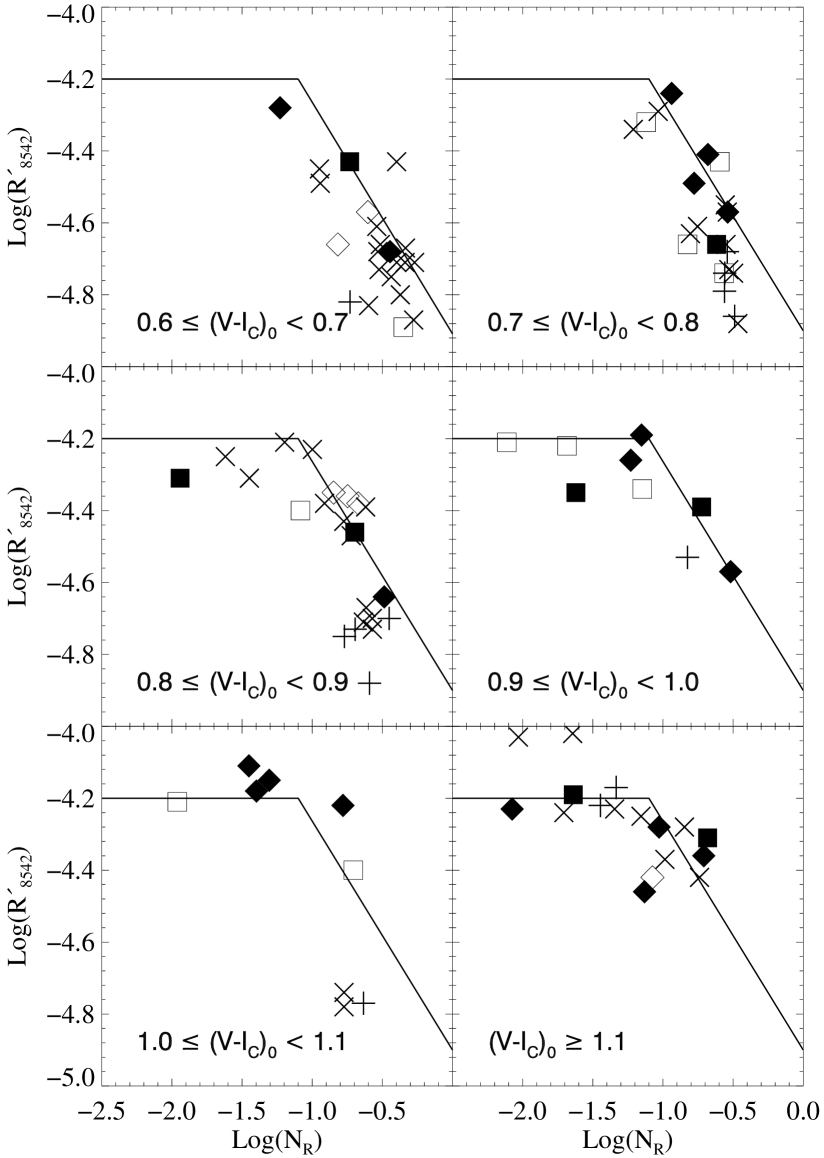

Figure 9 plots the Log of the coronal X-ray emission (divided by the star’s bolometric luminosity) and the Log of the chromospheric emission ratio for 8542Å line against the Log of the Rossby number for our stars in IC 2391/2602 with Figure 10 showing how the chromospheric emission changes with colour (unsurprisingly showing that redder stars are more active). Again, in both Figures, the coronal X-ray data for IC2391/2602 are from Patten & Simon (1996) and Stauffer et al. (1997), the coronal and chromospheric data for the Pleiades are from Stauffer et al. (1994), Micela et al. (1999), and Soderblom et al. (1993), and the NGC 6475 data are from James & Jeffries (1997).

.

As was shown in Figures 7 and 8, both the coronal and the chromospheric emission show a saturation level. Again, the coronal emission shows evidence of supersaturation (with a decrease in activity for Log(NR) -1.7), whereas the chromospheric emission shows little evidence of a decrease. The chromospheric saturation level is around Log(R′8542) -4.2. This is similar to that shown in the Ca II 8542Å emission for the Pleiades stars by Soderblom et al. (1993) and the NGC 6475 stars by James & Jeffries (1997). The scatter that the unknown inclination angle and estimated radius adds to Figure 9 for stars without a measured rotation period does not appear to be significant compared with the inherent scatter in the emission of the stars.

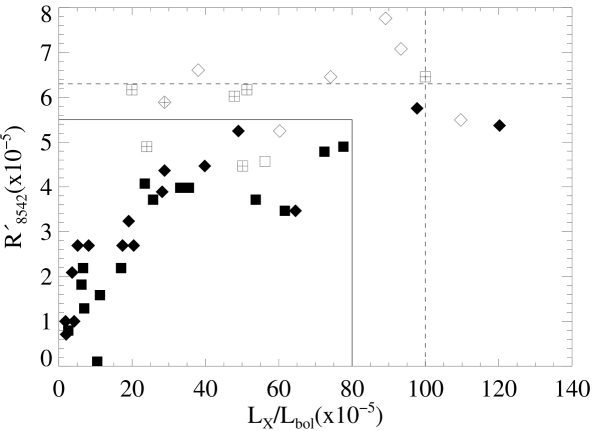

The onset of saturation appears to occur at around Log(NR) -1.0 for both the coronal and chromospheric emission. If saturation occurs at the same Rossby number then the relationship between the coronal and chromospheric emission should be linear approaching saturation. Ignoring those stars with activity around the saturation level (in either coronal or chromospheric emission), i.e. including only those stars in the box in Figure 11, there appears to be a change in the relationship between the two activity indicators for the stars in this study, between stars with LX/Lbol 20 x 10-5 (Log(LX/Lbol) -3.7) and those stars above this value. This change occurs below both the coronal and chromospheric saturation level and could indicate that coronal and chromospheric emission have a slightly different relationship for stars with low activity than for more active stars, rather than indicating a change in the onset of saturation. For stars more active than LX/Lbol 20 x 10-5 the relationship between the coronal and chromospheric emission (up to the saturation levels) could well be linear, but the scatter in the data is too large to determine if this is the case.

Ignoring the supersaturated stars, all but two of the stars within the box in Figure 11 (and two outside) have Log(NR) -1.14. This indicates that the Rossby number for the onset of saturation (for both coronal and chromospheric emission) is lower than Log(NR) = -1.0 indicated in Figure 9 and is probably closer to Log(NR) = -1.1. In addition, Figure 11 shows that all but three stars with both a small Rossby number, Log(NR) -1.14, and low coronal activity, LX/Lbol 60 x 10-5, (i.e. supersaturated) have Log(NR) -1.62, with only one star having a “normal” saturated level of coronal activity and a Log(NR) -1.62. This appears to indicate that coronal supersaturation is occurring at a slightly higher Rossby number than shown in Figure 9(a), possibly closer to log(NR) = -1.6.

5.6 Colour and Age Effects

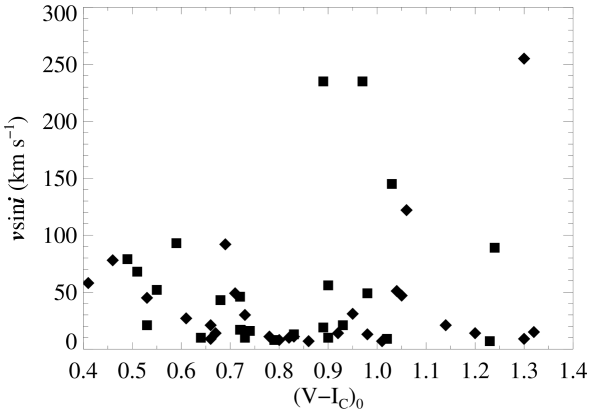

By the age of the Hyades 625 50 Myrs (Perryman et al., 1998), the rotation rate of a solar-type star can be reasonably determined based on its colour, with more massive stars showing higher rotation rates (Radick et al., 1987). However, due to the minimal amount of magnetic braking they have undergone, solar-type stars of the age of IC 2391 and IC 2602 should show a wide range of rotation rates for all colours. Figure 12 plots v sini against colour for the single stars in IC 2391 and IC 2602. As expected there is a wide range of v sini values (up to v sini = 100 km s-1) in the clusters regardless of the star’s colour, however the ultra-rapid rotators in the clusters are all redder than (V-IC)0 0.85. There is a small dip in the data around (V-IC)0 0.8, showing that there is a paucity of rapid rotators observed for this colour. We suggest that this is most likely just a statistical effect.

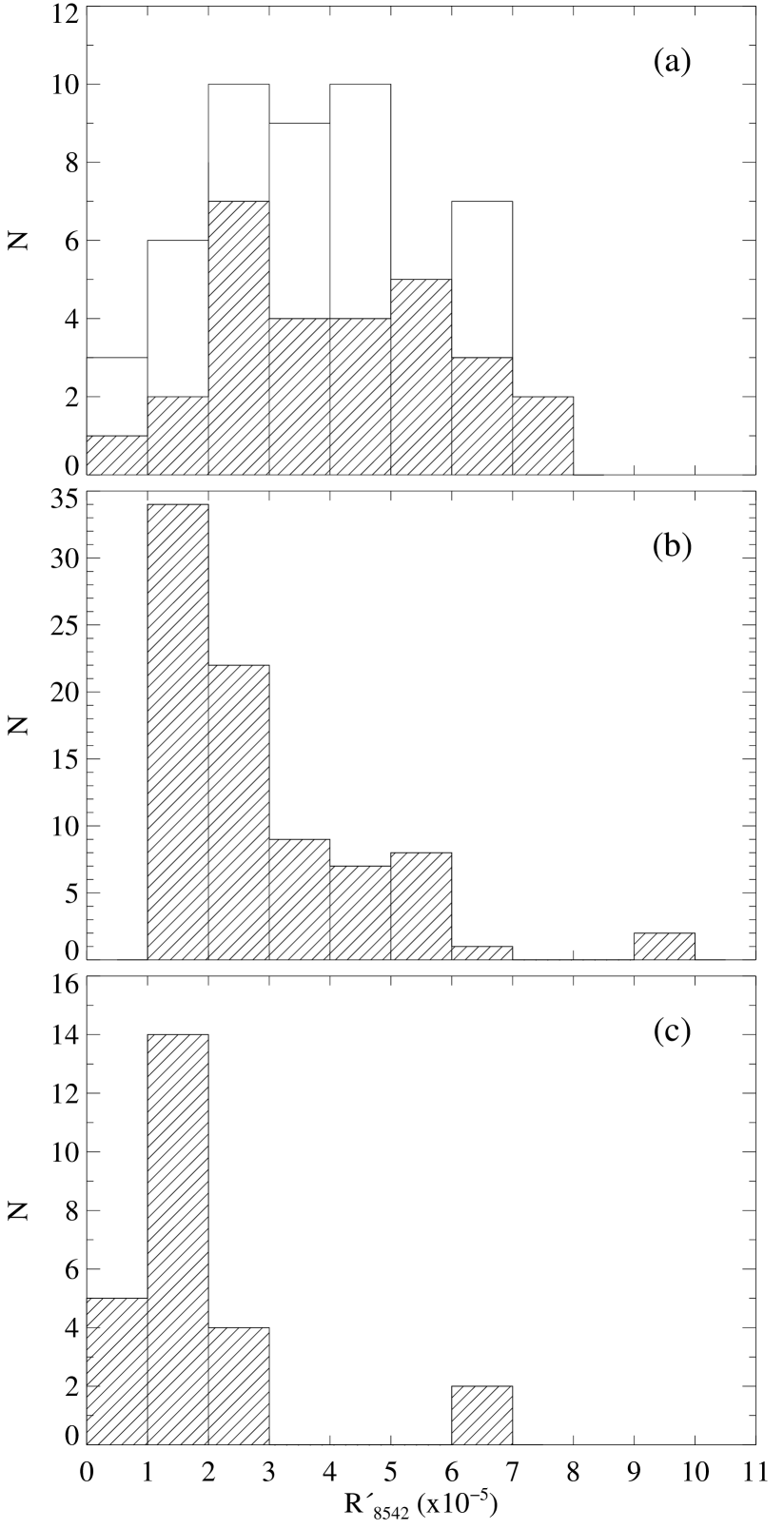

As stars age, their activity level falls as their rotation rate decreases through the loss of angular momentum via magnetic braking, i.e. Bouvier, Forestini & Allain (1997). Therefore it is expected that the overall activity levels of clusters should progressively shift to lower values for clusters of increasing age. There are two other young clusters for which the chromospheric emission ratio in the 8542Å line has been measured, the Pleiades (Soderblom et al., 1993) at an age of 130 20 Myrs according to the Lithium-depletion boundary method (Barrado y Navascués et al., 2004) and NGC 6475 (James & Jeffries, 1997) at an age of 220 Myrs. Figure 13 gives a histogram of the chromospheric emission ratios for IC 2391 and IC 2602, along with the ratios for the Pleiades and NGC 6475 clusters. The data for the Pleiades were taken from Soderblom et al. (1993) while the data for NGC 6475 were taken from James & Jeffries (1997). Most stars in IC 2391 and IC 2602 are seen to have a chromospheric emission level of around R′8542 2 to 5 x 10-5 compared to the Pleiades and NGC 6475, in which the peak is around R′8542 1 to 2 x 10-5. The median for IC 2391/2602 is R′8542 4.0 x 10-5, for the Pleiades the median is R′8542 2.2 x 10-5 (although this may be skewed by the fact that no star has R′8542 1.0 x 10-5) and the median is R′8542 1.7 x 10-5 for NGC 6475. As expected the median chromospheric activity level for the clusters drops with increasing cluster age, with IC 2391/2602 showing a much larger spread in chromospheric activity compared to the older clusters.

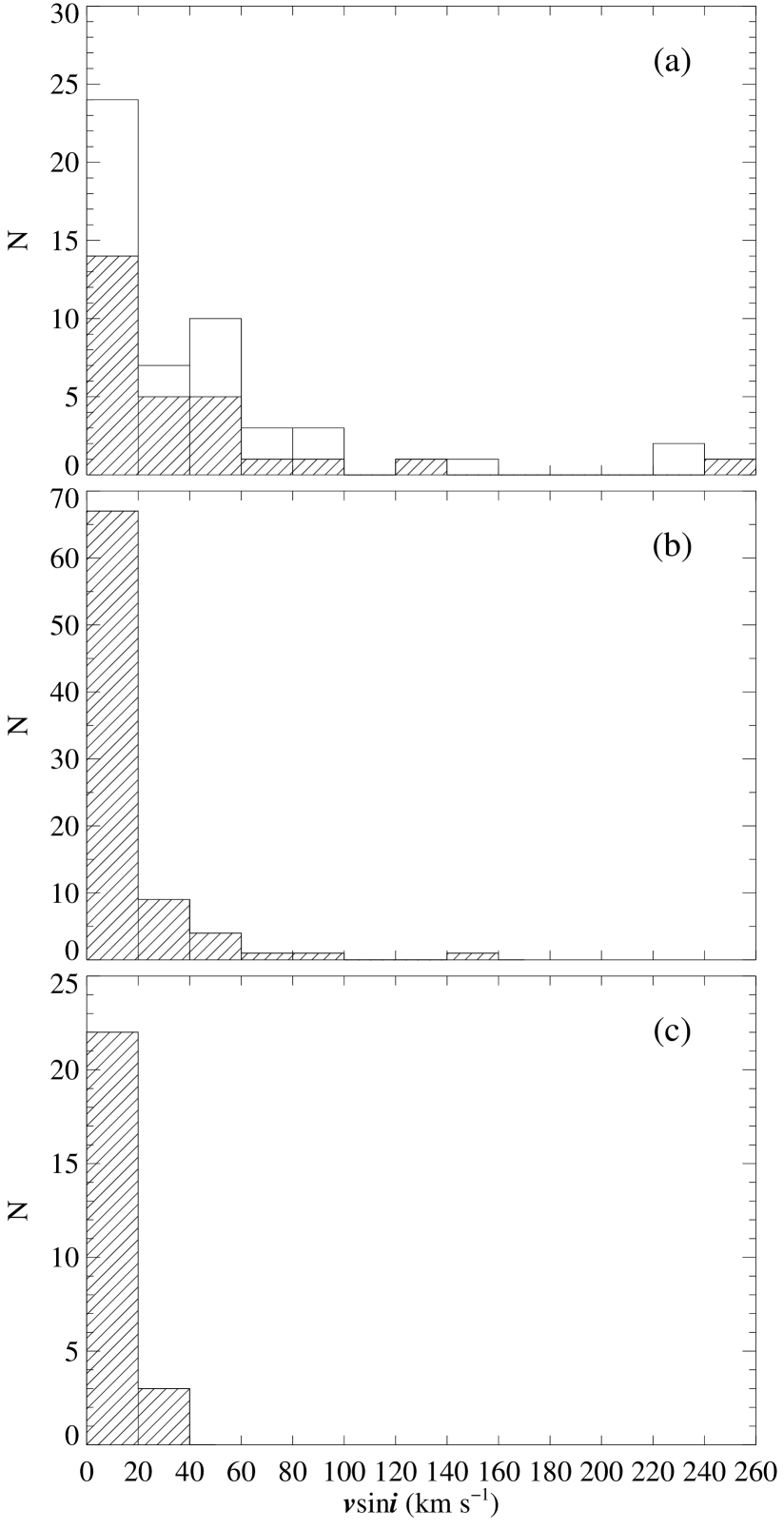

At the age of IC 2391 and IC 2602 the solar-type stars in the two clusters should have undergone no significant main-sequence braking and should represent the rotation rate with which they arrive (or will soon arrive) on the ZAMS. Figure 14 is a histogram of the measured v sini values for the single stars observed in the two clusters in this study, along with the v sini distributions for the Pleiades and NGC 6475. Again the Pleiades data are from Soderblom et al. (1993) and the NGC 6475 data are from James & Jeffries (1997). The number of slow rotators compared to fast rotators, using the division of v sini = 20 km s-1, is approximately even for IC 2391/2602 with 24 stars with v sini 20 km s-1 and 28 stars with v sini 20 km s-1. Thus 54% are rapid rotators. This is much the same as the similarly aged cluster NGC 2547 (lithium depletion boundary age 35 Myrs, Jeffries & Oliveira 2005) which has 50% - 60% (depending on the inclusion of possible binaries or not) of its solar-type stars as rapid rotators (Jeffries, Totten, & James, 2000). For the older clusters (Pleiades and NGC 6475) magnetic braking should have slowed many of the rapid rotators in the clusters. This can be seen in their v sini distributions, with the Pleiades having 67 stars with v sini 20 km s-1 and only 14 stars with v sini 20 km s-1, 18% rapid rotators. For NGC 6475 there are 23 stars with v sini 20 km s-1 and only 3 stars with v sini 20 km s-1, 12% rapid rotators. By the age of the Pleiades the median v sini of the cluster has decreased significantly from that of IC 2391/2602, with the median v sini of IC 2391/2602 = 21 km s-1, the Pleiades = 9 km s-1, and NGC 6475 = 8 km s-1.

When looking at the difference between the G stars (0.6 (B-V)0 0.9) and the early-K stars (0.9 (B-V)0 1.2) in IC 2391/2602 the percentage of rapidly rotating G stars is 34% while for early-K stars it is 58%. For the Pleiades the percentages are 15% for the G stars and 29% for the early-K stars. In NGC 6475 the rapid rotators makeup 0% of the G stars, but 33% of the early-K stars. Thus between the ages of IC 2391/2602 and the Pleiades the proportion of rapidly rotating G and K stars drops by about half (with the proportion of rapidly rotating G stars dropping slightly more than for the early-K stars). By the age of NGC 6475 there are no rapidly rotating G stars while the proportion of rapidly rotating early-K stars is similar to that of the Pleiades (although this may be influenced by the small number of early-K stars observed in NCG 6475; 2 of the 6 observed are rapid rotators).

The rotational evolution of cluster stars has been studied by a number of people including a recent study by Irwin et al. (2007) which includes rotational periods for a number of young clusters of varying ages, including rotational data from IC 2391/2602 stars. The observations presented in Irwin et al. (2007) show that the rotational period of G stars falls at a similar rate to that of K stars (from a peak around the IC 2391/2602 age) for clusters up to 200 Myrs. After this age the observations show that the rotation rate of G stars falls quite dramatically compared to that for K stars. This is in good agreement with the v sini results from IC 2391/2602, the Pleiades, and NGC 6475.

Irwin et al. (2007) have also modelled the angular momentum evolution of young clusters as they age, incorporating dynamo saturation into the models. The results indicate that a mass-dependent saturation velocity is required to reproduce the observations (taken into account via the mass-dependency of the Rossby number in our results, see § 5.5). Additionally, Irwin et al. (2007) found that while solid-body rotation can explain the evolution of the fastest rotators, core-envelope decoupling (with different rotations in the stellar core and envelope) appears to be required to explain the evolution of the slowest rotators.

6 Discussion

6.1 Chromospheric Saturation

Figure 9(a) gives the relationship between the coronal X-ray emission of the single solar-type stars in IC 2391 and IC 2602 and Rossby number. Figure 9(b) gives the same plot for the chromospheric emission ratio in the 8542Å line. For stars with Log(NR) -1.1 there is a saturation in the chromospheric emission at a level of around Log(R′8542) -4.2. This agrees well with the results of Soderblom et al. (1993) and James & Jeffries (1997), who found a saturation in the chromospheric emission ratio for solar-type stars in the Pleiades and NGC 6475 of a similar level. The saturation levels for the two other Calcium IRT lines at 8498Å and 8662Å are shown in Figure 8 and are Log(R′8498) -4.4 and Log(R′8662) -4.3. This confirms that, as expected, there is a saturation in the chromospheric emission of these cluster stars similar to that observed in the X-ray data from this and other clusters.

If all activity indicators show the onset of saturation at the same value of Rossby number, this would support the observed saturation being caused by the same mechanism (i.e. dynamo saturation). Figure 9 shows the onset of saturation is around Log(NR) -1.0 to -1.1 for both the coronal X-ray emission and the chromospheric. The chromospheric emission in both H and the 8542Å line from the Pleiades dwarfs also show the onset of saturation at around Log(NR) -1.0 (Soderblom et al., 1993). However, Cardini & Cassatella (2007) show that for the Mg II emission in a range of stars (including those in IC 2602) the onset of saturation occurs around Log(NR) -0.7 (with a saturation level of Log(FMgII) 6.3). Thus the onset of saturation for the Mg II emission appears to occur at a slightly higher Rossby number than what we find for the Ca II emission but may be within the error bars as Cardini & Cassatella (2007) calculated the Rossby number empirically themselves rather than using the Noyes et al. (1984) value. In other work, the measurement of stellar activity using V (optical light curve amplitude, used as a proxy for covering fraction of starspots) by O’Dell et al. (1995), shows the onset of saturation only for Log(NR) -1.5, if at all (using the Noyes et al. (1984) c values). This is long after both coronal and chromospheric saturation have set in, but more recent work by Krishnamurthi et al. (1998) has questioned the use of V as an activity indicator.

Thus we conclude that both the chromospheric and coronal emission appear to be saturating at a similar Rossby number. This supports the idea that both coronal and chromospheric saturation are caused by the same mechanism.

What are the possible mechanisms behind saturation? Jardine & Unruh (1999) have suggested that the effect of saturation seen in X-ray emission could be the result of a reduction in the coronal X-ray emitting volume due to centrifugal stripping of the corona for rapid rotators. As rotation rate increases, the co-rotation radius of the star decreases. Jardine & Unruh (1999) suggest that around the saturation velocity the co-rotation radius moves inside the X-ray emitting corona. The rise in gas pressure then breaks the magnetic loops to form open field regions that are dark in X-rays. As rotation increases the reduction in emitting volume is balanced by a rise in the density of the corona leading to saturation. While this idea explains coronal (X-ray) saturation, it cannot be used to explain chromospheric saturation. To explain chromospheric saturation, Jardine & Unruh (1999) suggest that another mechanism, such as the enhanced continuum emission proposed by Doyle (1996) may be responsible. However, if coronal and chromospheric saturation are controlled by two different mechanisms it would be unlikely (but not impossible) that they would saturate at the same Rossby number. Thus the Jardine & Unruh (1999) explanation would appear to be unlikely.

Another suggestion to explain coronal saturation has been put forward by Stȩpień et al. (2001) who suggest that coronal saturation is the result of the coronal emitting regions of a star being completely filled. This, we assume, would similarly be happening to the chromospheric emission regions to account for chromospheric saturation. In this scenario the onset of saturation could conceivably occur at similar Rossby number for both coronal and chromospheric emission, if both are caused by strong magnetic fields erupting through the stellar surface and extending into the chromosphere and corona. However, as explained below, this idea appears to fall down when trying to explain supersaturation.

Finally it should be noted that a different explanation for saturation (but not supersaturation) has been put forward by Barnes (2003). He argues that saturation is just the effect of a different dynamo in operation in rapidly-rotating stars, a convective rather than an interface dynamo. Such an explanation is supported by the finding of large regions of azimuthal magnetic field on the surfaces of young rapidly-rotating solar-type stars (i.e. Donati et al., 2003; Marsden et al., 2006), which have been explained by the operation of a dynamo distributed throughout the convection zone (Donati et al., 2003). Barnes (2003) claims that saturated stars should all be located on what he calls the convective sequence (see Barnes, 2003, Figure 2). However, this is just saying that saturated stars are more rapidly-rotating than non-saturated stars (i.e. rapidly-rotating stars are more active) which is obvious and thus our results provide no way of determining if the Barnes (2003) explanation is correct.

6.2 Chromospheric Supersaturation?

A further complication to the problem of saturation is the effect of supersaturation. The X-ray emission from the IC 2391 and IC 2602 stars, when plotted against Rossby number in Figure 9(a), shows the supersaturation effect occurring around Log(NR) -1.6. This has been seen in the X-ray emission of other young cluster stars (Pizzolato et al., 2003; Stauffer et al., 1997; Patten & Simon, 1996; Randich et al., 1996; Prosser et al., 1996b), and has also been seen, to a lesser extent, in the X-ray emission of W UMa and M dwarf stars (Stȩpień et al., 2001; James et al., 2000). This study included measurements of the chromospheric emission of 5 stars in IC 2391 and IC 2602 with (V-IC)0 0.6 and v sini values 100 km s-1, including 3 stars with v sini values 200 km s-1. The chromospheric emission for the IC 2391 and IC 2602 stars, Figures 7(b), 8, and 9(b), show little evidence of a decrease in chromospheric emission for stars with v sini 100 km s-1 or Log(NR) -1.6. Thus, it would appear that either supersaturation does not exist for the chromospheric emission of ultra-rapid rotators, or it occurs at a rotation rate significantly greater than that for coronal emission.

It should be noted that due to the massive broadening of the spectral lines with such high v sini values, the accuracy of fitting of the inactive star to the target star can have an impact on the level of emission measured. However, a change of Log(R′8542) from -4.2 to -4.5 (which would be required to have a similar supersaturation effect to that seen in the X-ray emission) is about twice what we estimate the error in Log(R′8542) to be (see § 5.4.1) which we consider unlikely.

Our Calcium infrared triplet results are supported by the results of Randich (1998) which show no supersaturation in the H emission of ultra-rapid rotators in the 50-Myr old -Persei cluster. In addition, the Mg II study of cluster and field stars by Cardini & Cassatella (2007) also shows no evidence of supersaturation, however the lowest Log(NR) value they have for their stars is greater than -1.6, so they are not really within the supersaturation regime.

In contrast to our results, a study of a number of active stars of spectral type K2 or later by Scholz et al. (2007) has shown tentative evidence for supersaturation in the H emission of two stars with v sini values around 100 km s-1. However, these are true pre-main sequence objects and the swollen convection zone of such objects may act differently to that of more zero-age main-sequence stars we have studied. This is supported by Feigelson et al. (2003) and Preibisch et al. (2005) who find a changed (from that for ZAMS stars) X-ray activity - Rossby number relationship for the pre-main sequence stars in the Orion nebula.

Like saturation, the factors causing supersaturation are still open to debate. Stȩpień et al. (2001) have proposed that supersaturation is a result of the poleward migration of active coronal regions, leaving the equator void of active regions and thus decreasing the coronal filling factor of the star. The fact that the chromospheric emission observed in this paper shows little evidence of supersaturation would count against this model being the mechanism for supersaturation, as it would be expected that a poleward movement of active regions would also affect the chromospheric emission.

Such a trend in the motion of active regions is also not evidenced in the Doppler imaging of spot topologies of young active stars. Many of the stars Doppler imaged show rather similar spot patterns often with polar or high latitude spots and some lower latitude features. Comparing the Doppler images of stars from IC 2391/2602 in both the saturation (R58, v sini = 92 km s-1) and supersaturation (VXR45A, v sini = 235 km s-1) regime show similar spot maps (Marsden et al., 2004) with no evidence of a further poleward migration of active regions for the supersaturated star.

The coronal stripping model of Jardine & Unruh (1999) discussed previously could account for supersaturation. As the co-rotation radius continues to decrease with an increase in rotation rate, eventually enough of the coronal volume is forced open and the X-ray emission falls with rotation rate. Jardine (2004) has used this model to explain both the modulation (observed by Marino et al. 2003) and supersaturation of the X-ray observations of the ultra-rapid rotator VXR45A. If the coronal stripping model is correct then it would be unlikely that chromospheric emission would show any evidence of supersaturation as centrifugal stripping will only affect the coronae of these stars. Thus the observations presented in this paper, showing no chromospheric supersaturation, are consistent with the coronal stripping model of Jardine & Unruh (1999). Unfortunately, as mentioned previously, the fact that both the chromospheric and coronal emission show the onset of saturation at a similar Rossby number would appear to count against this model.

Thus the mechanisms causing both saturation and supersaturation remain elusive.

7 Conclusions

In this paper we have reported on the chromospheric emission levels of over 50 solar-type F, G, and K stars in the young open clusters IC 2391 and IC 2602. Due to their youth, IC 2391 and IC 2602 contain a number of star that can be classified as ultra-rapid rotators (v sini 100 km s-1) and thus are excellent targets to determine if chromospheric emission shows signs of supersaturation.

We have redetermined v sini values for all our targets in both clusters and determined v sini values for a number of targets (especially those ultra-rapid rotators) for the first time. The clusters show a wide range of v sini values for most colours studied (0.4 (V-IC)0 1.4) although there is a deficit of rapid rotators around (V-IC)0 0.8, which we believe has just occurred by chance.

We have shown that chromospheric emission saturates for stars with Log(NR) -1.1. The saturation levels found are Log(R′8542) -4.2, Log(R′8498) -4.4, and Log(R′8662) -4.3, for the three Calcium IRT lines at 8542Å, 8498Å, and 8662Å respectively. The chromospheric saturation level in the 8542Å line agrees well with that for two older clusters, NGC 6475 and the Pleiades (James & Jeffries, 1997; Soderblom et al., 1993). Both activity indicators appear to be saturating at a similar Rossby number which lends weight to the saturation seen being caused by a single mechanism, which remains unknown.

Significantly, chromospheric emission from these stars shows little evidence of the effect of supersaturation seen in the coronal X-ray emission of the same stars. Thus we believe that X-ray supersaturation is not a result of an overall decrease in the efficiency of the magnetic dynamo in ultra-rapid rotators.

Acknowledgments

The observations for this paper were taken with Anglo-Australian Telescope. We would like to thank the technical staff of the Anglo-Australian Observatory for their excellent assistance during these observations. We would also like to thank the referees (Rob Jeffries and an anonymous referee) for their comments that helped greatly improve this manuscript. SCM was funded by a University of Southern Queensland PhD scholarship during the course of this work. This research has made use of the WEBDA database, operated at the Institute for Astronomy of the University of Vienna.

References

- Barnes (2003) Barnes S., 2003, ApJ, 586, 464

- Barnes & Sofia (1996) Barnes S., Sofia S., 1996, ApJ, 462, 746

- Barnes et al. (1999) Barnes S. A., Sofia S., Prosser C. F., Stauffer J. R., 1999, ApJ, 516, 263

- Barrado y Navascués et al. (2004) Barrado y Navascués D., Stauffer J. R., Jayawardhana R., 2004, ApJ, 614, 386

- Bessel & Stringfellow (1993) Bessell M. S., Stringfellow G. S., 1993, in Burbidge G., Layzer D., Sandage A., eds., Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Vol. 31, Annual Reviews Inc., Palo Alto, California, p. 433

- Bessell et al. (1998) Bessell M. S., Castelli F., Plez B., 1998, A&A, 333, 231

- Bouvier et al. (1997) Bouvier J., Forestini M., Allain S., 1997, A&, 326, 1023

- Braes (1961) Braes L. L. E., 1961, Monthly Notices of the Astronomical Society of South Africa, 20, 7

- Braes (1962) Braes L. L. E., 1962, Bulletin of the Astronomical Institutes of the Netherlands, 16, 297

- Buscombe (1965) Buscombe W., 1965, MNRAS, 129, 411

- Caldwell et al. (1993) Caldwell J.A.R., Cousins A.W.J., Ahlers C.C., van Wamelan P., Maritz E.J., 1993, South African Astronomical Observatory Circulars, 15, 1

- Cardini & Cassatella (2007) Cardini D., Cassatella A., 2007, ApJ, 666, 393

- Chmielewski (2000) Chmielewski Y., 2000, A&A, 353, 666

- D’Antona & Mazzitelli (1997) D’Antona F., Mazzitelli I., 1997, in Micela G., Pallavicini R., Sciortino S., eds., Memorie della Societa astronomia Italiana, Vol. 68, Cool stars in clusters and associations: Magnetic activity and age indicators, Societa astronomia Italiana, p.807

- Donati et al. (1997) Donati J.-F., Semel M., Carter B., Rees D. E., Cameron A. C., 1997, MNRAS, 291, 658

- Donati et al. (2003) Donati J.-F., Collier Cameron A., Semel M., et al., 2003, MNRAS, 345, 1145

- D’Orazi & Randich (2009) D’Orazi V., Randich S., 2009, A&A, accepted (arXiv:0905.1835)

- Doyle (1996) Doyle J. G., 1996, A&A, 307, L45

- Feigelson et al. (2003) Feigelson E. D., Gaffney III J. A., Garmire G., Hillenbrand L. A., Townsley L., 2003, ApJ, 584, 911

- Foing et al. (1989) Foing B. H., Crivellari L., Vladilo G., Rebolo R., Beckman J. E., 1989, A&A Supp. Ser., 80, 189

- Hogg (1960) Hogg A. R., 1960, PASP, 72, 85

- Irwin et al. (2007) Irwin J., Hodgkin S., Aigrain S., Hobb L., Bouvier J., Clarke C., Moraux E., Bramich D. M., 2007, MNRAS, 377, 741

- James & Jeffries (1997) James D. J., Jeffries R.D., 1997, MNRAS, 291, 252

- James et al. (2000) James D. J., Jardine M. M., Jeffries R. D., Randich S., Collier Cameron A., Ferreira M., 2000, MNRAS, 318, 1217

- Jardine (2004) Jardine M., 2004, A&A, 414, L5

- Jardine & Unruh (1999) Jardine M., Unruh Y. C., 1999, A&A, 346, 883

- Jeffries & Oliveira (2005) Jeffries R. D., Oliveira J. M., 2005, MNRAS, 358, 13

- Jeffries et al. (2000) Jeffries R. D., Totten E. J., James D. J., 2000, MNRAS, 316, 950

- Kim & Demarque (1996) Kim Y.-C., Demarque P., 1996, ApJ, 457, 340

- Krishnamurthi et al. (1997) Krishnamurthi A., Pinsonneault M. H., Barnes S., Sofia S., 1997, ApJ, 480, 303

- Krishnamurthi et al. (1998) Krishnamurthi A., Terndrup D. M., Pinsonneault M. H., et al., 1998, ApJ, 493, 914

- Kurucz (1993) Kurucz R. L., 1993, CDROM #13 (ATLAS9 atmospheric models) and CDROM #18 (ATLAS9 and SYNTHE routines, spectral line database)

- Linsky et al. (1979) Linsky J. L., Hunten D. M., Sowell R., Glackin D. L., Kelch W. L., 1979, ApJ Supp. Ser., 41, 481

- Lyngȧ (1961) Lyngȧ G., 1961, Arkiv för Astronomii, 2, 379

- Mallik (1997) Mallik S. V., 1997, A&A Supp. Ser., 124, 359

- Marino et al. (2003) Marino A., Micela G., Peres G., Sciortino S., 2003, A&A, 407, L63

- Marino et al. (2005) Marino A., Micela G., Peres G., Pillitteri I., Sciortino S., 2005, A&A, 430, 287

- Marsden et al. (2004) Marsden S. C., Waite I. A., Carter B. D., Donati J.-F., 2004, Astron. Nachr., 325, 246

- Marsden et al. (2006) Marsden S. C., Donati J.-F., Semel M., Petit P., Carter B. D., 2006, MNRAS, 370, 468

- Mestel & Spruit (1987) Mestel L., Spruit H. C., 1987, MNRAS, 226, 57

- Micela et al. (1999) Micela G., Sciortino S., Harnden Jr F.R., et al., 1999, A&A, 341, 751

- Nordström et al. (2004) Nordström B., Mayor M., Anderson J., et al., 2004, A&A, 418, 989

- Noyes et al. (1984) Noyes R. W., Hartmann L. W., Baliunas S. L., Duncan D. K., Vaughan A. H., 1984, ApJ, 279, 763

- O’Dell et al. (1995) O’Dell M. A., Panagi P., Hendry M. A., Collier Cameron A., 1995, A&A, 294, 715

- Patten (1995) Patten B. M., 1995, PhD thesis, University of Hawaii

- Patten & Simon (1996) Patten B. M., Simon T., 1996, ApJ, Supp. Ser., 106, 489

- Perry & Bond (1969) Perry C. L., Bond H. E., 1969, PASP, 81, 629

- Perry & Hill (1969) Perry C. L., Hill G., 1969, AJ, 74, 899

- Perryman et al. (1998) Perryman M.A.C., Brown A.G.A., Lebreton Y., et al., 1998, A&A, 331, 81

- Pinsonneault et al. (1998) Pinsonneault M. H., Stauffer J., Soderblom D. R., King J. R., Hanson J. B., 1998, ApJ, 504, 170

- Pizzolato et al. (2003) Pizzolato N., Maggio A., Micela G., Sciortino S., Ventura P., 2003, A&A, 397, 147

- Platais et al. (2007) Platais I., Melo C., Mermilliod J.-C., Kozhurina-Platais V., Fulbright J. P., Méndez R. A., Altmann M., Sperauskas J., 2007, A&A, 461, 509

- Preibisch et al. (2005) Preibisch T., Kim Y.-C., Fatava F., et al., 2005, ApJ Supp. Ser., 160, 401

- Prosser et al. (1996a) Prosser C. F., Randich S., Stauffer J. R., 1996a, AJ, 112, 649

- Prosser et al. (1996b) Prosser C. F., Randich S., Stauffer J. R., Schmitt J. H. M. M., Simon T., 1996b, AJ, 112, 1570

- Radick et al. (1987) Radick R.R., Thompson D.T., Lockwood G.W., Duncan D.K., Baggett W.E., 1987, ApJ, 321, 459

- Randich (1998) Randich S., 1998, in Donahue R.A., Bookbinder J.A., eds., Cool Stars, Stellar Systems and the Sun 10, ASP Conference Series, Vol.154, p.501

- Randich (2001) Randich S., 2001, A&A, 377, 512

- Randich et al. (1995) Randich S., Schmitt J. H. M. M., Prosser C. F., Stauffer J. R., 1995, A&A, 300, 134

- Randich et al. (1996) Randich S., Schmitt J. H. M. M., Prosser C. F., Stauffer J. R., 1996, A&A, 305, 785

- Randich et al. (1997) Randich S., Aharpour N., Pallavicini R., Prosser C. F., Stauffer J. R., 1997, A&A, 323, 86

- Randich et al. (2001) Randich S., Pallavicini R., Meola G., Stauffer J. R., Balachandran S. C., 2001, A&A, 372, 862

- Scholz et al. (2007) Scholz A., Coffey J., Brandeker A., Jayawardhana R., 2007, ApJ, 662, 1254

- Soderblom et al. (1993) Soderblom D. R., Stauffer J. R., Hudon J. D., Jones B. F., 1993, ApJ Supp. Ser., 85, 315

- Stauffer et al. (1989) Stauffer J., Hartmann L. W., Jones B. F., McNamara B. R., 1989, ApJ, 342, 285

- Stauffer et al. (1994) Stauffer J.R., Caillault J.-P., Gangé M., Prosser C.F., Hartmann L.W., 1994, ApJ Supp. Ser., 91, 625

- Stauffer et al. (1997) Stauffer J. R., Hartmann L. W., Prosser C. F., Randich S., Balachandran S., Patten B. M., Simon T., Giampapa M., 1997, ApJ, 479, 776

- Stȩpień et al. (2001) Stȩpień K., Schmitt J. H. M. M., Voges W., 2001, A&A, 370, 157

- Valenti & Fischer (2005) Valenti J. A., Fischer D. A., 2005, ApJ Supp. Ser., 159, 141

- van Leeuwen (1999) van Leeuwen F., 1999, A&A, 341, L71

- Whiteoak (1961) Whiteoak J. B., 1961, MNRAS, 123, 245