The equivariant cohomology ring of a cohomogeneity-one action

Abstract

We compute the rational Borel equivariant cohomology ring of a cohomogeneity-one action of a compact Lie group.

1. Introduction

Cohomogeneity-one Lie group actions—that is, those whose orbit space is one-dimensional—form an intensively-studied class of examples which are a next natural object of study after homogeneous actions. In lieu of a necessarily incomplete attempt to summarize the vast geometric literature surrounding these actions, we content ourselves with a gesture toward the substantial bibliography to be found in the recent classificatory work of Galaz-García and Zarei [GGZ15].

Given the prominence of these actions, it is natural to wonder what can be said of their equivariant cohomology. Due to earlier work of two of the authors [GM14, GM17], it is known the rational Borel equivariant cohomology ring is Cohen–Macaulay, and structure theorems for this ring have been worked out in special cases [GM14, Cor. 4.2, Props. 5.1, 5.10] along with topological consequences for the manifold acted on. In this work, we describe the equivariant cohomology rings of a certain broad class of cohomogeneity-one actions (delineated precisely in the discussion after Theorem˜3.3), obtaining more explicit expressions in the case of actions on manifolds.

In the most interesting case, where the space acted on by a compact, connected Lie group is a manifold and the orbit space is a closed interval, Theorem˜3.2, due mostly to Mostert, implies can be written up to -equivariant homeomorphism as the double mapping cylinder of a pair of quotient maps for some closed subgroups of . By work of Galaz-García–Searle (Theorem˜3.3), the same holds if is an Alexandrov space. As such, the equivariant Mayer–Vietoris sequence is applicable to the cover of by the preimages of two subintervals of .111 The non-equivariant Mayer–Vietoris sequence of the same cover has also long been used to study such spaces [GrH87, Hoel10, EU11]. As the equivariant cohomology of the restricted actions is well-known, this approach would in general recover the additive structure up to an extension problem, but in our case, surprisingly, we are able to determine the entire ring structure. This is Section˜3.2. In Section˜5, we prove more explicit formulas depending on the numbers in the case is a manifold , so that are homology spheres. In the following result and throughout, will denote the Borel -equivariant cohomology ring of a point with rational coefficients. In fact, all cohomology will take rational coefficients unless explicitly specified otherwise.

theoremHodd

Let be the double mapping cylinder

of the quotient maps for closed subgroups of a compact Lie group

such that are homology spheres.

(a)

Assume is odd-dimensional

and even-dimensional,

and the bundle is orientable.

Then we have an -algebra isomorphism

where

for a certain class ,

the product is determined by the injection

,

and the -module structure is induced

by the inclusions .

If is a sphere, then is

the Euler class of the sphere bundle

.

(b)

Assume that both are odd-dimensional

and the bundles are both orientable.

Then we have an -algebra isomorphism

where for classes and the -module structure is induced by the inclusions . If is a sphere, then is the Euler class of the sphere bundle .

In the event both spheres are even-dimensional, the generators of the Weyl groups with respect to a shared maximal torus generate a dihedral subgroup of the automorphisms of this torus, of order . It is this that figures in the following result.

theoremHeven Let the double mapping cylinder of the quotient maps for closed subgroups of a compact Lie group such that are even-dimensional spheres, and the bundles are both orientable. Then the number is even, and we have an -algebra isomorphism

where the injections are induced by the inclusions and the -module structure is induced by .

Cohomogeneity-one actions whose orbit space is arise as mapping tori of right translations of homogeneous spaces by elements , and this case admits a parallel but much more easily-proved statement we discuss in Section˜3.1.

theoremcircle Let be the mapping torus of the right translation by on the homogeneous space of a compact Lie group . Then one has - and -algebra isomorphisms

respectively, where the -module structure is given by pullback from in both cases and the -algebra structure is induced by the inclusion .

The unexpectedly great utility of the Mayer–Vietoris sequence in our situation results from an additional structural feature of the sequence that seems not to be frequently noted, namely the fact that the connecting map preserves a module structure over the cohomology ring of the whole space. This result is proved in Section 2.

Acknowledgments. The authors would like to thank the referee for careful proofreading, for suggesting a reference, and for making an important correction to their statement of Theorem˜3.2. The first author would like to thank Omar Antolín Camarena for helpful conversations and the National Center for Theoretical Sciences (Taiwan) for its hospitality during a phase of this work.

2. The Mayer–Vietoris sequence

Let be a topological group, a -space, and two -invariant subsets whose interiors cover . The rings and in the Mayer–Vietoris sequence inherit an -module structure by restriction. It is clear the restriction maps between these rings are -module homomorphisms and we claim the connecting map is as well. It is enough to prove the analogous result for singular cohomology, as the Mayer–Vietoris sequence in equivariant cohomology is just the Mayer–Vietoris sequence of the associated cover of the homotopy orbit space .

Proposition 2.1.

Let be a topological space, and a pair of subspaces whose interiors cover , and any commutative ring with unity. Then the connecting map in the Mayer–Vietoris sequence of is a homomorphism of -modules.

Proof.

The covering hypothesis makes the inclusion of singular chain complexes a quasi-isomorphism, whose dual is then again a quasi-isomorphism. The Mayer–Vietoris sequence in cohomology is the long exact sequence arising from the short exact sequence of cochain complexes

where and . To define the connecting map, given a homogeneous cocycle , one selects cochains and such that , and then is the class represented by the unique element of such that . Now given a class in , the restrictions of some representative to , and factor through the representative . Observe that . But since , we have , so as claimed. ∎

Remark 2.2.

This feature turns out not to be specific to Borel equivariant cohomology, but applies to multiplicative cohomology theories in general, and the first author proves this fact and an extension of Section˜3.2 to other cohomology theories in an accompanying paper [Car18], along with analogues of the other main results in equivariant K-theory.

3. Equivariant cohomology rings

To deploy Proposition 2.1 as promised, we need the structure theorem for cohomogeneity-one actions on manifolds.

Theorem 3.2 ([Most57a, Thm. 4][Most57b][GGZ15, Thm. A]).

Let be a compact, connected Lie group acting continuously with cohomogeneity one on a connected topological manifold without boundary. Then is, up to -equivariant homeomorphism, as follows.

-

•

If , there is a closed subgroup such that .

-

•

If , there are a closed subgroup and an element such that is the mapping torus of the right translation of by . (The equivariant homeomorphism type of the resulting space depends only on the class of in .)

-

•

If , there are closed subgroups such that is either a sphere or the Poincaré homology sphere and is the open mapping cylinder of the projection .

-

•

If , there are closed subgroups such that each of is either a sphere or the Poincaré homology sphere and is the double mapping cylinder

of the projections .

Conversely, these constructions yield only cohomogeneity-one -actions on manifolds. In the cases where has boundary, admits a -invariant smooth structure if and only if no isotropy quotient or is .

Before proceeding, we note the noncompact cases are trivial for our purposes, since in these cases equivariantly deformation retracts to the cohomogeneity-zero case . There is a similar classification of cohomogeneity-one actions on closed Alexandrov spaces.

Theorem 3.3 ([GGS11, Thm. A]).

Let be a compact Lie group acting effectively and isometrically with cohomogeneity one on a closed (i.e., compact and without boundary) Alexandrov space . Then is, up to -equivariant homeomorphism, as follows.

-

•

If , there are a closed subgroup and an element such that is the mapping torus of the right translation of by (and hence, by Theorem˜3.2, a smooth manifold).

-

•

If , there are closed subgroups such that are positively-curved homogeneous spaces and is the double mapping cylinder of the projections .

Conversely, these constructions yield only cohomogeneity-one -actions on Alexandrov spaces.

Thus our Section˜3.2 will apply more generally than just to manifolds. Because of these two classification results, it is reasonable to focus our attention in the rest of the paper on cohomogeneity-one actions of the following types:

-

•

the mapping torus of a right translation on a homogeneous space or

-

•

the double mapping cylinder of a span of projections .

3.1. Mapping tori

By Theorem˜3.2, if the orbit space of a cohomogeneity-one action is a circle, the space in question can be assumed to be a manifold , the mapping torus of the right-translation of some element on , and hence actually a smooth manifold .

Lemma 3.4.

Let be a topological space, a self-homeomorphism of such that some finite power is homotopic to , and the mapping torus of . Then

Proof.

Note that admits an -sheeted cyclic covering by the mapping torus of , which is homeomorphic to the mapping torus of the identity. The covering action is conjugate to a -action on under which acts, up to homotopy, as , which, rotating the circle component, is in turn homotopic to . A standard lemma on the transfer map [Hat02, Prop. 3G.1] then gives

3.2. Double mapping cylinders

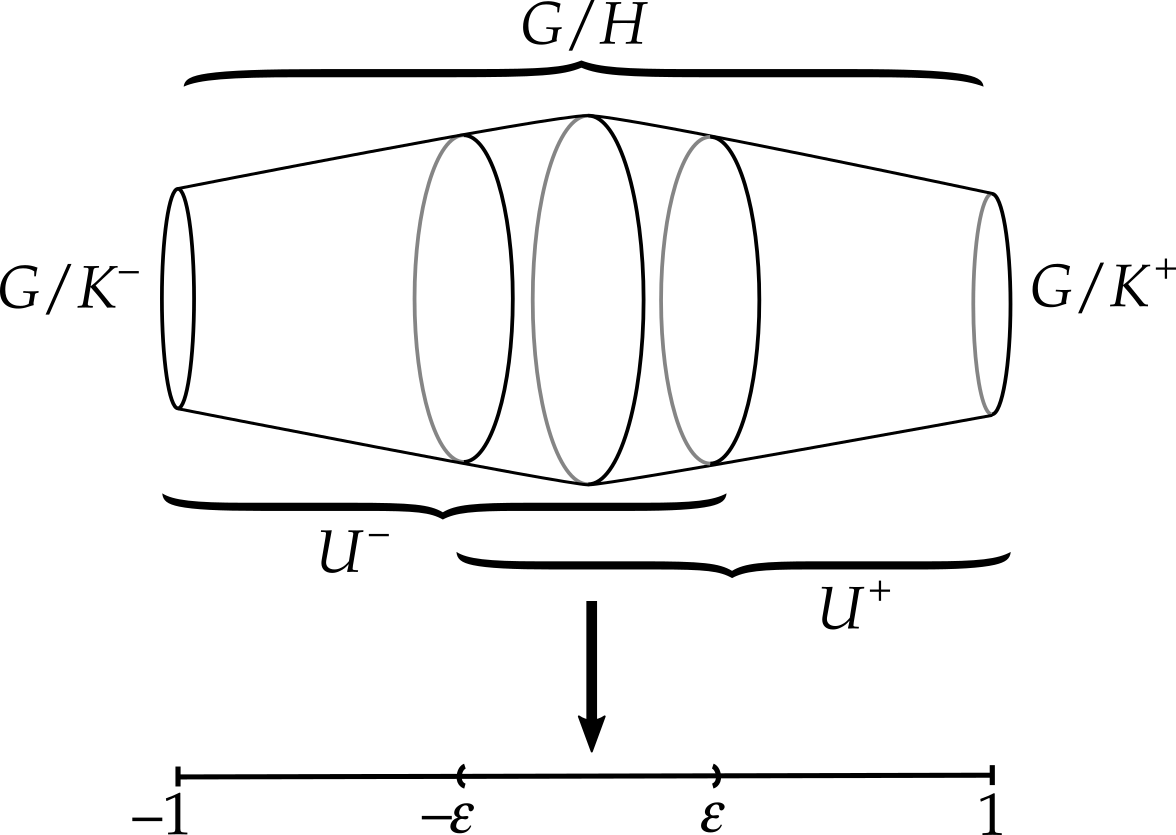

Let be a compact Lie group and any closed subgroups. Then the double mapping cylinder of admits the obvious invariant open cover by the respective inverse images and of the subintervals and , for some small , of depicted in Figure˜3.1. Their intersection equivariantly deformation retracts to and to in such a way that the inclusions correspond to the projections . Now we can apply Proposition˜2.1.

theoremmainH Let be the double mapping cylinder of the projections . Then one has a graded -algebra and a graded -module isomorphism, respectively:

where are induced by the inclusions and denotes the fiber product.222 That is, is the subring of pairs such that . The multiplication of odd-degree elements is zero, and the product descends from the multiplication of in that

for and the image of .

Proof.

For any we have homeomorphisms . As and are concentrated in even degree, the Mayer–Vietoris sequence of the cover just discussed reduces to a four-term exact sequence

so that is the kernel and the cokernel of the middle map . The multiplicative structure on follows from the fact is a ring map, the description of the product follows from Proposition˜2.1, and the fact the product is zero follows from the observation is injective on and yet for any elements . ∎

Example 3.5.

Let with and block-diagonal. We have , where is the first Pontrjagin class of the tautological bundle over the infinite Grassmannian , so .

Example 3.6.

In the situation where , the resulting double mapping cylinder is just the unreduced suspension . One has

4. Maps of classifying spaces

In the event the cohomogeneity-one double mapping cylinder is a manifold , we will presently see that more precise descriptions of can be obtained depending on the dimensions of the isotropy spheres , subject to an orientation hypothesis on the left action of in case these groups are disconnected, and these descriptions depend crucially on the structure of as a module over .

Lemma 4.1.

Let be compact Lie groups such that is a homology sphere. The -bundle is orientable if and only if left multiplication on by any element of induces the identity in cohomology.

Proof.

Recall orientability of a fiber bundle is defined as triviality of the action of the fundamental group of the base on the cohomology of the fiber. To determine the action-up-to-homotopy of a class of on the fiber, lift a representative loop to a path in starting at and ending at some . Then for any in the fiber , the path lifts to , starting at and ending at , which we may define to be . Under the identification given by , this is just the action of induced by the defining homogeneous action of on . The generator is invariant trivially, so the action is trivial in cohomology if and only if the fundamental class is fixed by the -action. ∎

Remark 4.2.

Particularly, this rules out the case going forward.

Proposition 4.3 (Cf. Goertsches–Mare [GM14, Prop. 3.1][GM17, Prop. 4.2]).

Let be compact Lie groups such that is a homology sphere of odd dimension and is an orientable -bundle. Then is a surjection and can be written

where is the generalized Euler class of the bundle .

Proof.

Let be the identity component of and write , so that is a homeomorphism. We claim is a polynomial ring. This follows if is a sphere of dimension at least since then is both simply-connected and covered by , forcing . If is homeomorphic to or the Poincaré homology sphere , then we still know , but the action of on is trivial because it is known [GM14, Pf., Prop. 3.1][GM17, Pf., Prop. 4.2] that is normal in in these cases, so the action of is the restriction of an action of , which is homotopically trivial since is path-connected.333 To make this account self-contained, the proof of normality is thus. The transitive action of on induces a map whose image, which acts effectively by definition, can only be itself if and if [Bre61, Thm. 1.1]. As stabilizes all points, it is in particular contained in . The stabilizer of the coset under the effective action of is , which must be finite since is of rank one, so is of finite index in ; particularly, its identity component must be . Since is normal in by definition, so also must be .

We now consider the map of -bundles

| (4.1) |

The left map is equivariant with respect to the right -action, inducing an effective right action of such that the right map is the quotient, and so we may identify [Hat02, Prop. 3G.1] the map with the map of invariants . Now let us consider a portion of the induced map of generalized Gysin sequences [MiT00, SS3.7]:

The commutativity of the diagram implies the identification takes the one generalized Euler class to the other, or in other words that the class in the lower sequence is -invariant. Since is a polynomial ring, multiplication by is injective, so the horizontal maps before and after are zero, so this is actually an inclusion of short exact sequences. As the image of multiplication by is precisely the principal ideal , we obtain an -equivariant isomorphism . As is a -equivariant surjection between graded polynomial rings over on and generators, respectively, whose kernel is generated by the -invariant element , Lemma˜4.6 applies to yield a -equivariant isomorphism . This restricts to an isomorphism of -invariants . ∎

Remark 4.4.

When is a sphere, the generalized Euler class featuring in Proposition˜4.3 is well known to be the standard Euler class of a sphere bundle [MiT00, Thm. 5.17, pp. 145–6]. If , on the other hand, from the fact that the action factors through an subgroup [Bre61, Thm. 1.1], one can associate to the principal -bundle and show is times the first Pontrjagin class .

Remark 4.5.

The persistent orientability hypothesis is necessary; we will see in Remark˜5.3 that Section˜5.2 fails without this hypothesis. For now, consider the case of and a subgroup of order generated by an element of determinant . Then for we have . We have and in the notation of the proof since . The proof would go through if we had , but we do not; in fact , where is represented by the first Pontrjagin class of the tautological -plane bundle over the infinite Grassmannian [Hat09, Thm. 3.16(a)]. Thus, although it is incidentally true in this case that , the proof of Proposition˜4.3 cannot possibly go through.

Lemma 4.6.

Suppose is a graded polynomial ring in finitely many variables over equipped with an action of a finite group fixing the field of constants , and is a -invariant homogeneous element of such that is again a polynomial ring. Then there is a -invariant graded -subalgebra such that and is a ring isomorphism.

Proof.

We consider and as modules over the group ring . It is easy to see that any -module complementary to will be taken bijectively and -linearly to by , so we just need to show such a complement can be chosen to be a ring and generators of this ring can be chosen such that together with they form a set of -algebra generators for . We write for the graded -module of indecomposables, in this case a free module. As is a finite-dimensional -representation and the order of is invertible over , we may break into irreducible representations of , which are cyclic -modules, each generated by an element . We may lift each of these to a homogeneous element . By construction, the union of the -orbits of the forms a set of -algebra generators for . Now let be a -preimage of . Then the -algebra generated by the is taken bijectively onto by , so it is a polynomial subalgebra and in fact another -linear complement to . It is clear from the isomorphism that each element of can be represented uniquely as a polynomial in over . ∎

The case is even-dimensional is simpler.

Proposition 4.7 ([Bor53, Thm. 26.1(a)][Sam41, p. 1121]).

Let be compact Lie groups of equal rank. Then is injective. This applies particularly if is an even-dimensional sphere. In this case, if the bundle is orientable and , then is a free -module of rank two on and a lift of the fundamental class of under the surjection .

Samelson showed the ranks are equal if is an even-dimensional sphere and the injectivity statement is due to Borel.

Proof.

The covering coming from the action of on , induces an isomorphism by a standard transfer lemma [Hat02, Prop. 3G.1]. As is a polynomial ring by Borel’s theorem, the Serre spectral sequence of is concentrated in even degree and so collapses. By Lemma˜4.1, the coefficients are simple, so as an -module for some represented by in the associated graded algebra. ∎

Remark 4.8.

Note that the basis is preserved under the map

induced by the map of -bundles , so may be chosen -invariant.

Remark 4.9.

The lift in Proposition˜4.7 can be chosen to be the pullback under of the universal Euler class . To see this, note that by the classification of transitive Lie group actions on spheres [Bes87, Ex. 7.13], the action must factor through a subgroup isomorphic to , sending into an subgroup and hence inducing a map of -bundles from to . Both Serre spectral sequences collapse at , and the map sends . But represents , and since as an -module, represents .

5. Double mapping cylinders which are manifolds

In this section we are in the situation of Section˜3.2 and additionally the isotropy quotients are homology spheres.

5.1. The case when one of is odd-dimensional

If is odd-dimensional, then is surjective, so vanishes by Section˜3.2 and is easily described.

*

Proof.

(a) Since the map is reduction modulo by Proposition˜4.3 and is an injection by Proposition˜4.7, the fiber product is the subring of consisting of the direct summands and . We may identify the former with and the latter with , and the two interact multiplicatively via the rule .

(b) Using Proposition˜4.3 to make identifications such that is reduction modulo , we see the fiber product is the subring of comprising the three direct summands

on which multiplication is determined by the three rules

so the map to sending is a ring isomorphism. ∎

Remark 5.1.

The second and fourth author have shown [GM14, GM17] that for any cohomogeneity-one action of a compact, connected Lie group on a compact, connected topological manifold , the equivariant cohomology is a Cohen–Macaulay module over . In the special case when all the hypotheses of Section˜1 are fulfilled, this result can be recovered easily from that theorem. Concretely, in case (a), the equivariant cohomology is a direct sum of two Cohen–Macaulay modules over and in case (b) it is an algebra over finitely generated as an -module and Cohen–Macaulay as a ring.

5.2. The case when both of are even-dimensional

In this subsection we assume that , , and have all three the same rank, or equivalently that is a manifold with even-dimensional. We start with the special case where .

propositionspherefiber Assume , that is an even-dimensional sphere, and that the bundle is orientable. Then we have an -algebra isomorphism

where the -algebra structure is induced by the inclusion .

Proof.

In this case is the homotopy pushout of , which we may write as the quotient of by the relation collapsing the ends to one copy of each. There is an obvious map

The fiber of this map over is the unreduced suspension , so is a sphere bundle. We claim the Serre spectral sequence of has simple coefficients and collapses at . Indeed, given and a loop representing a class in , if is a lift to starting at and ending at , a lift of starting at (respectively, ) ends at (resp., ). This action fixes the poles of the fiber and acts as left multiplication by on each latitude , fixing the orientation of the latitude by Lemma˜4.1, so the action preserves the orientation of the fiber of as a whole, and thus, again by Lemma˜4.1, the bundle is orientable. As there are only two nonzero rows, to see the spectral sequence collapses at , it is enough to show . But this differential must be zero because admits the section , showing is injective. The collapse shows is surjective and as a module over . Thus and any preimage of the fundamental class generate as an -module.

By definition, this commutes with all elements of , and we claim it also squares to zero. Indeed, from Section˜3.2, it is in the image of the Mayer–Vietoris connecting map from , which factors as , where is the suspension isomorphism and is the map that collapses each end of the double mapping cylinder to a point [May99, SS19.1–3, pp. 146–7]. Since the cup product on is identically zero and is the image of a square in , we see that indeed . It follows as an -algebra. ∎

Remark 5.3.

The orientability hypothesis in the proposition above is essential, as can be seen from the action of on described by Mostert [Most57a, Thm. 7]. The isotropies are given by and , so and the bundle is not orientable by Remark˜4.2. If the conclusion of Proposition 5.2 held in this instance, we would have (with coefficients as usual)

| (5.1) |

But the -action at hand is equivariantly formal [GM14, Cor. 1.3], so is isomorphic as an -module to , which unlike is zero in dimension .

Example 5.4.

Let us now use Section˜5.2 to compute the equivariant cohomology of the action arising from the inclusion diagram . For a nice treatment of this manifold we refer to Püttmann [Pütt09, Sect. 4.3]. From the Mayer–Vietoris sequence, one sees the manifold has the same integral cohomology as the direct product . By Proposition 5.2,

Equivariant formality of the -action on was already known over [GM14, Cor. 1.3], but the inclusion induces an -module isomorphism , so the action is actually equivariantly formal over .

We will now generalize the proposition above to the case when and are not necessarily equal. Assume that for . Let be a maximal torus and the subgroup of generated by the Weyl groups and . The Weyl groups, and hence , are all contained in the image of the conjugation map sending . Since image of this map is compact and is discrete, is finite. Because are even-dimensional spheres, by Proposition˜4.7, is of rank two over , so is an index-two subgroup of each of and hence normal. It follows is also normal in , and we will be particularly interested in the quotient group . Note that the involutions also generate , so the latter must be a dihedral group. Because we will be considering functions on the Lie algebra , in the rest of this section, cohomology will take real or complex coefficients.

Definition 5.5.

It is easy to see every component of contains some element of , and such elements in the same component differ by an element of , so there is a well defined action of on the fixed point set and one has

as in the connected case.

Lemma 5.6.

The action of the dihedral group on is effective.

Proof.

We show any element of that fixes pointwise is already in . If is the subgroup of generated by and , then clearly

| (5.2) |

By Molien’s theorem [Kan01, SS17-3], given any action of a finite group on a real vector space , the Poincaré series in of is a polynomial in the variable with leading coefficient . In our case, this shows , so is in as claimed. ∎

Remark 5.7.

Assume that is connected and smooth and equipped with a -invariant Riemannian metric and a complete geodesic in meeting each orbit orthogonally. The Weyl group of is defined [PT87, SS4][AA93, SS5] to be , where is the setwise stabilizer of and the pointwise. The account of Alekseevsky–Alekseevsky [AA93, SS4,5] shows acts transitively on the set of such , so we may assume passes through ; it can also be shown is the common stabilizer of all points of in , so , and it follows passes through as well. Further, there are unique involutions acting antipodally on the spheres and generating as a dihedral subgroup of .

One might hope from this account that the groups and are isomorphic, but they are typically not, as we will see in Example˜5.15. There is at least a homomorphism from the one to the other, which is an isomorphism if . To construct it, observe first that since all maximal tori in are conjugate, for any there exists an such that , and this specification uniquely determines the left coset , defining a homomorphism from ; to see multiplicativity, note that for given , we may make the choice . It is not hard to see the kernel is , so there is an induced monomorphism

Following with the map sending to conjugation of by , we obtain a map . When restricted to , this takes values in , so there is a restricted map as claimed. When , the map is injective, so and is an isomorphism.

We henceforth write for the dihedral group , where is the order of . Our remaining goal is the following.

*

This will follow from an analysis of the action of on .

Lemma 5.8.

Let be a complex representation of . Set and so that . Write for the root of unity and for the -eigenspace of .

-

•

The transformations and agree on and are opposite on if is even.

-

•

Both and exchange each with .

Proof.

From now on, we specialize Lemma˜5.8 to the case . We write also .

Lemma 5.9.

There exist such that and .

Proof.

Note that since , the -eigenspace of is . Recall that Proposition˜4.7 gives a -basis for ; now is a -eigenvector for and is another -module basis for . ∎

Let us now consider the -eigenspace decompositions where for . Since the interchange with by Lemma˜5.8, one finds , and specifically that , and if is even, . All told, the decomposition is

| (5.4) |

where the last term is taken to be zero if is odd.

Lemma 5.10.

In (5.4) only one term is non-zero. Explicitly, the elements each lie either in , in , or in for .

Proof.

Lemma 5.11.

Exactly one of the following cases obtains:

-

(i)

and , and one can rescale in such a way that .

-

(ii)

and .

-

(iii)

and , and there is one relatively prime to such that and up to rescaling,

for the same single element . Moreover, .

Proof.

This is a case analysis following Lemma˜5.10.

(i) The case one of lies in

Suppose and, for a contradiction, suppose is minimal such that there exists a nonzero for some indivisible by . Then is a -eigenvector of , hence divisible by by Lemma˜5.9. We must have for otherwise the component of in would contradict minimality of . Thus by Lemma˜5.8, so by Lemma˜5.8 and divides by Lemma˜5.9. It follows, again lest we contradict minimality of , that and so . But then, by Lemma˜5.8 again, so divides by Lemma˜5.9 and we have

contradicting the fact has minimal degree in the -eigenspace of . Thus in fact . Since then acts trivially but Lemma˜5.6 states the action of is effective, it follows . By Lemma˜5.8 the actions of and agree on , so the -eigenspace decompositions of in Lemma˜5.9 coincide and by rescaling we may assume .

(ii) The case one of lies in

If , then in fact , for we could otherwise produce from any nonzero homogeneous , where does not divide , an element of smaller degree with a nonzero component in . It follows acts as the identity on , and since the action of is effective by Lemma˜5.6, we have and . As for , consulting Lemma˜5.10, it must lie in or , but if it lay in we would be in the previous case.

(iii) The case both lie in for some with

We first note that , for if we had, say, , then by Lemma˜5.9, would act as the identity on ; but this would imply is equal to , which could only happen if and .

Next we claim . As already mentioned, the -eigenspace of in is , which lies in Since the -eigenspaces of on are and hence both are of dimension , but the -eigenspace is trivial except for , it follows all the other terms in are zero, so and . Thus we may rescale to take as claimed.

To see that and are coprime, first note that , for given a putative nonzero homogeneous element such that does not divide , the component of in would be nonzero of smaller degree. Thus acts trivially on , and since the -action is effective by Lemma˜5.6, it follows . ∎

Lemma 5.12.

The elements are prime elements of .

Proof.

Recall from Remark˜4.8 that the basis element from Proposition˜4.7 may be taken -invariant. Thus the same holds of the eigenvectors defined in Lemma˜5.9. It is clear in that are irreducible, for all elements of lesser degree lie in the -eigenspace . Since is a polynomial ring, the principal ideals are prime. In fact, the ideals are prime in as well, for given such that , we know one of the two, say , is divisible by in . But then as is -invariant as well, is also divisible by in . ∎

Lemma 5.13.

Write for the joint -eigenspace of . Then

are isomorphisms.

All unelaborated claims in the proof are clauses of Lemma˜5.8.

Proof.

Write so that we have a direct sum decomposition . This decomposition is invariant under , so inherit such decompositions and

Because , the first direct summand is the common -eigenspace of on , whose complement is . We will be done if we can show the second summand is all of .

-

•

If is even, acts on as multiplication by , so . Thus decomposes as the sum of the -eigenspace of on and its -eigenspace, which is .

-

•

If , then since acts as on , we have for nonzero , so for nonzero , we cannot have in . Thus the -eigenspaces of are disjoint, and since for all , their sum is all of .∎

We are now finally in a position to prove Proposition 1.

Proof of Proposition 1.

We proceed through the trichotomy of Lemma˜5.11, in each case applying Section˜3.2.

(i) The case and

In this case the actions of coincide by Lemma˜5.8, so the images of the injections agree. Thus

(ii) The case and and .

We show and apply Lemma˜5.13; since , the result will then follow from Section˜3.2. Suppose lies in . From Lemma˜5.9 we know is divisible by both and . Note that by Lemma˜5.8. As sends to , we see divides the latter as well. The quotient is in the joint -eigenspace .

(iii) The case for some .

We will find an element of degree such that and apply Lemma˜5.13. Since generate all , we have for any . Particularly, is also divisible by the , which we explicitly enumerate. Writing , from Lemma˜5.8 we obtain relations and which suffice to show that if we consider elements only up to nonzero complex multiples, the sets

are equal. Since and are relatively prime by Lemma˜5.11.(iii), the elements for are all distinct elements, none a scalar multiple of any other since their -components are equal, and prime by Lemma˜5.12. Since each divides , their product also divides . Note that

But the right-hand side is a -eigenvector of , so lies in . ∎

We now illustrate Section˜1 with some examples.

Example 5.14.

There is a cohomogeneity one action of on the sphere with isotropy groups , , and [GWZ08, Table E]. Observe that and we have . Using Remark˜5.7 and the table in Grove et al. [GWZ08], one deduces that . Here is just the quotient ring , which admits a natural -action permuting the generators . Within we have and , whose intersection is . Section˜1 implies

This is in fact a known result, being equivalent to the equivariant formality of the action [GM14, Cor. 1.3] since there is only one possible graded -algebra structure for a free graded -module on generators of degrees and .

Similar calculations can be made for any of the last five examples in Grove et al. [GWZ08, Table E]. Note that they are all equivariantly formal actions. This is not the case in the next example.

Example 5.15.

The left action of on itself given by has cohomogeneity one [Pütt09, Example 5.5]. One can see that relative to the canonical metric on , there is a transversal geodesic segment joining the two singular orbits, along which the isotropies are , , and . The Weyl group turns out to be , but the induced symmetry group is just , so we are in the case . If we write for a generator of , then the canonical maps send and both isomorphically to . Since , one concludes

Remark 5.16.

Again, as in Remark˜5.1, one can deduce directly that for and as in Section˜1, is Cohen–Macaulay as an -module. This time, one notices that the equivariant cohomology is the direct sum of two copies of , the latter being a -algebra which is finitely generated as an -module and Cohen–Macaulay as a ring.

Remark 5.17.

When is also equal to , the -action is equivariantly formal. In this case is odd-dimensional and the situation is particularly nice because the restricted action of a maximal torus of is of GKM type in a sense recently defined by the third author [He16, Example 4.17].

References

- [AA93] Andrey V. Alekseevsky and Dmitry V. Alekseevsky. Riemannian -manifold with one-dimensional orbit space. Ann. Global Anal. Geom., 11(3):197–211, 1993. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00773366.

- [Bes87] Arthur Besse. Einstein manifolds, volume 10 of Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete, 3. Folge. Springer, 1987.

- [Bor53] Armand Borel. Sur la cohomologie des espaces fibrés principaux et des espaces homogènes de groupes de Lie compacts. Ann. of Math. (2), 57(1):115–207, 1953. http://jstor.org/stable/1969728.

- [Bre61] Glen E. Bredon. On homogeneous cohomology spheres. Ann. of Math., pages 556–565, 1961. http://jstor.org/stable/1970317.

- [BtD85] Theodor Bröcker and Tammo tom Dieck. Representations of compact Lie groups, volume 98 of Grad. Texts in Math. Springer, 1985.

- [Car18] Jeffrey D. Carlson. The equivariant K-theory of a cohomogeneity-one action. 2018. arXiv:1805.00502.

- [CK11] Suyoung Choi and Shintarô Kuroki. Topological classification of torus manifolds which have codimension one extended actions. Algebr. Geom. Top., 11(5):2655–2679, 2011. http://projecteuclid.org/euclid.agt/1513715302, arXiv:0906.1335.

- [EU11] Christine M. Escher and Shari K. Ultman. Topological structure of candidates for positive curvature. Topology Appl., 158(1):38–51, 2011. doi:10.1016/j.topol.2010.10.001.

- [GGS11] Fernando Galaz-García and Catherine Searle. Cohomogeneity one Alexandrov spaces. Transform. Groups, 16(1):91–107, 2011. arXiv:0910.5207.

- [GGZ15] Fernando Galaz-García and Masoumeh Zarei. Cohomogeneity one topological manifolds revisited. Math. Z., 2015. URL: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00209-017-1915-y, arXiv:1503.09068.

- [GM14] Oliver Goertsches and Augustin-Liviu Mare. Equivariant cohomology of cohomogeneity one actions. Topology Appl., 167:36–52, 2014. arXiv:1110.6318.

- [GM17] Oliver Goertsches and Augustin-Liviu Mare. Equivariant cohomology of cohomogeneity-one actions: The topological case. Topology Appl., 2017. arXiv:1609.07316.

- [GrH87] Karsten Grove and Stephen Halperin. Dupin hypersurfaces, group actions and the double mapping cylinder. J. Differential Geom., 26(3):429–459, 1987. doi:10.4310/jdg/1214441486.

- [GWZ08] Karsten Grove, Burkhard Wilking, and Wolfgang Ziller. Positively curved cohomogeneity one manifolds and 3-Sasakian geometry. J. Differential Geom., 78:33–111, 2008. http://projecteuclid.org/euclid.jdg/1197320603.

- [Hat02] Allen Hatcher. Algebraic topology. Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002. http://math.cornell.edu/˜hatcher/AT/ATpage.html.

- [Hat09] Allen Hatcher. Vector bundles and K-theory. 2009 manuscript. http://math.cornell.edu/˜hatcher/VBKT/VBpage.html.

- [He16] Chen He. Localization of certain odd-dimensional manifolds with torus actions. 2016. arXiv:1608.04392.

- [Hoel10] Corey A. Hoelscher. On the homology of low-dimensional cohomogeneity one manifolds. Transform. Groups, 15(1):115–133, 2010.

- [Kan01] Richard Kane. Reflection groups and invariant theory, volume 5 of C. M. S. Books in Mathematics. Springer, 2001.

- [Kur11] Shintarô Kuroki. Classification of torus manifolds with codimension one extended actions. Transf. Groups, 16(2):481–536, Jun 2011. doi:10.1007/s00031-011-9136-7.

- [May99] J. Peter May. A concise course in algebraic topology. University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- [MiT00] Mamoru Mimura and Hiroshi Toda. Topology of Lie groups, I and II, volume 91 of Transl. Math. Monogr. Amer. Math. Soc., Providence, RI, 2000.

- [Most57a] Paul S. Mostert. On a compact Lie group acting on a manifold. Ann. of Math., 65(3):447–455, 1957. http://jstor.org/stable/1970056.

- [Most57b] Paul S. Mostert. Errata: On a compact Lie group acting on a manifold. Ann. of Math., 66(3):589, 1957. http://jstor.org/stable/1969911.

- [PT87] Richard Palais and Chuu-Lian Terng. A general theory of canonical forms. Trans. Amer. Math. Soc., 300:771–789, 1987. URL: http://ams.org/journals/tran/1987-300-02/S0002-9947-1987-0876478-4/.

- [Pütt09] Thomas Püttmann. Cohomogeneity one manifolds and selfmaps of nontrivial degree. Transform. Groups, 14:225–247, 2009. URL: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00031-008-9037-6, arXiv:0710.3770.

- [Sam41] Hans Samelson. Beiträge zur Topologie der Gruppen-Mannigfaltigkeiten. Ann. of Math., 42(1):1091–1137, Jan 1941. http://jstor.org/stable/1970463.

- [Seg68] Graeme Segal. The representation-ring of a compact Lie group. Publ. Math. Inst. Hautes Études Sci., 34:113–128, 1968. http://numdam.org/item/PMIHES_1968__34__113_0.

Department of Mathematics, University of Toronto

jcarlson@math.toronto.edu

Fachbereich Mathematik und Informatik, Philipps-Universität Marburg

goertsch@mathematik.uni-marburg.de

Yau Mathematical Sciences Center, Tsinghua University

che@math.tsinghua.edu.cn

Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Regina

mareal@math.uregina.ca