marginnote \restoresymbolorigmarginnotemarginnote \jvolAA \jyearYYYY

The Interstellar Dust Properties of Nearby Galaxies

Abstract

This article gives an overview of the constitution, physical conditions and observables of dust in the interstellar medium of nearby galaxies. We first review the macroscopic, spatial distribution of dust in these objects, and its consequence on our ability to study grain physics. We also discuss the possibility to use dust tracers as diagnostic tools. We then survey our current understanding of the microscopic, intrinsic properties of dust in different environments, derived from different observables: emission, extinction, polarization, depletions, over the whole electromagnetic spectrum. Finally, we summarize the clues of grain evolution, evidenced either on local scales or over cosmic time. We put in perspective the different evolution scenarios. We attempt a comprehensive presentation of the main observational constraints, analysis methods and modelling frameworks of the distinct processes. We do not cover the dust properties of the Milky Way and distant galaxies, nor circumstellar or active galactic nucleus torus dust.

doi:

10.1146/((please add article doi))keywords:

ISM: dust, Magellanic clouds, nearby galaxies, methods1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 The Interstellar Dust: a Key Galaxy Component

Interstellar grains are solid particles of sizes , made of heavy elements (mainly O, C, Si, Mg, Fe) available in the InterStellar Medium (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISM]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar medium\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@0) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ). They appear to be rather uniformly mixed with the gas. Although accounting for of the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISM]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar medium\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@1) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ mass, they have a radical impact on galaxies, as they scatter and absorb starlight. In normal disk galaxies, they re-radiate in the InfraRed (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@2) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ) about of the stellar power, and up to in ultraluminous \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@3) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ galaxies (e.g. Clements et al., 1996). In addition, they are responsible for the heating of the gas in PhotoDissociation Regions (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[PDR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Photodissociation region\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@4) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ), by photoelectric effect (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[PE]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Photoelectric\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@5) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ; Draine, 1978). They are also catalysts of numerous chemical reactions, including the formation of the most abundant molecule in the Universe, H2 (Gould & Salpeter, 1963).

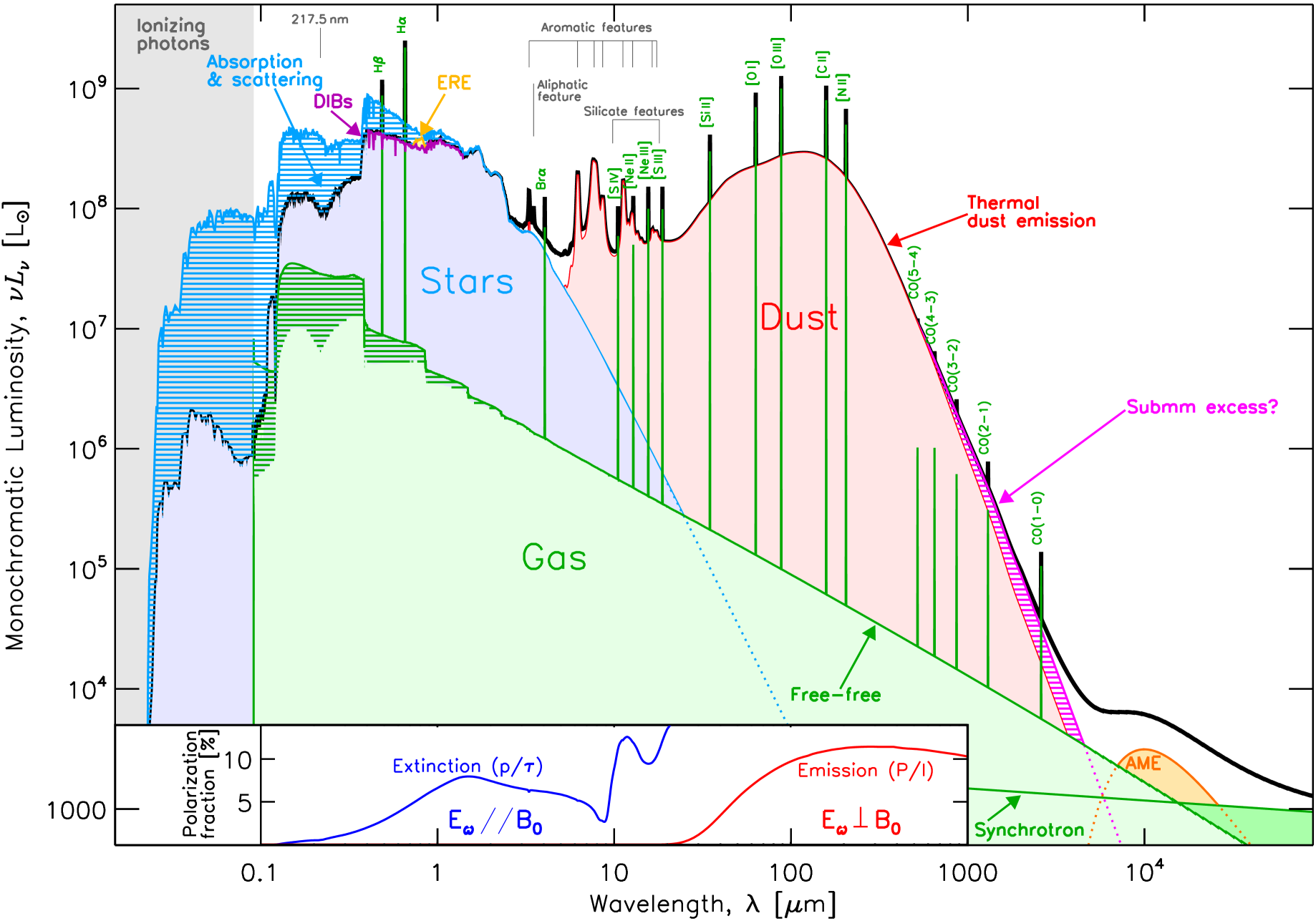

A detailed knowledge of the grain properties is crucial to study the lifecycle of the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISM]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar medium\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@6) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ and galaxy evolution, as it is needed to: (1) unredden \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[UV]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Ultraviolet\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@7) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ -visible observations; (2) study deeply embedded regions; (3) build reliable diagnostics of the physical conditions and of the evolutionary stage of a galaxy or a star forming region; (4) provide accurate prescriptions in photoionization and photodissociation models, and simulations of the star formation process. However, as we will show in this review, there remains several uncertainties about the grain properties and their evolution. Dust physics is characterized by the great complexity of its object. The number of ways to combine elements to build interstellar solids is virtually limitless and has consequences on the longevity of the particle and its observables. The progress in this field is thus mainly driven by empirical constraints: observations over the whole electromagnetic spectrum (Figure 1); and laboratory experiments on dust analogs.

[h]

2 WHAT ARE THE “DUST PROPERTIES”?

2.0.1 Dust mixture constitution

The constitution of a grain mixture is defined by: (1) the chemical composition of the bulk material and its stoichiometry; (2) the structure of the grains (crystalline, amorphous, porous, aggregated, etc.); (3) the presence of heterogeneous inclusions; (4) the presence of organic and/or icy mantles; (5) the shape of the grains; (6) their size distribution; (7) their abundance relative to the gas.

2.0.2 Dust physical conditions

A dust mixture, with a given constitution, can experience different physical conditions: (1) thermal excitation of the grains, due to radiative heating (equilibrium or stochastic), or to collisional heating in a hot plasma; (2) grain charging by exchange of electrons with the gas; (3) alignment of elongated grains on the magnetic field; (4) grain rotation (relevant for the smallest sizes).

2.0.3 Dust observables

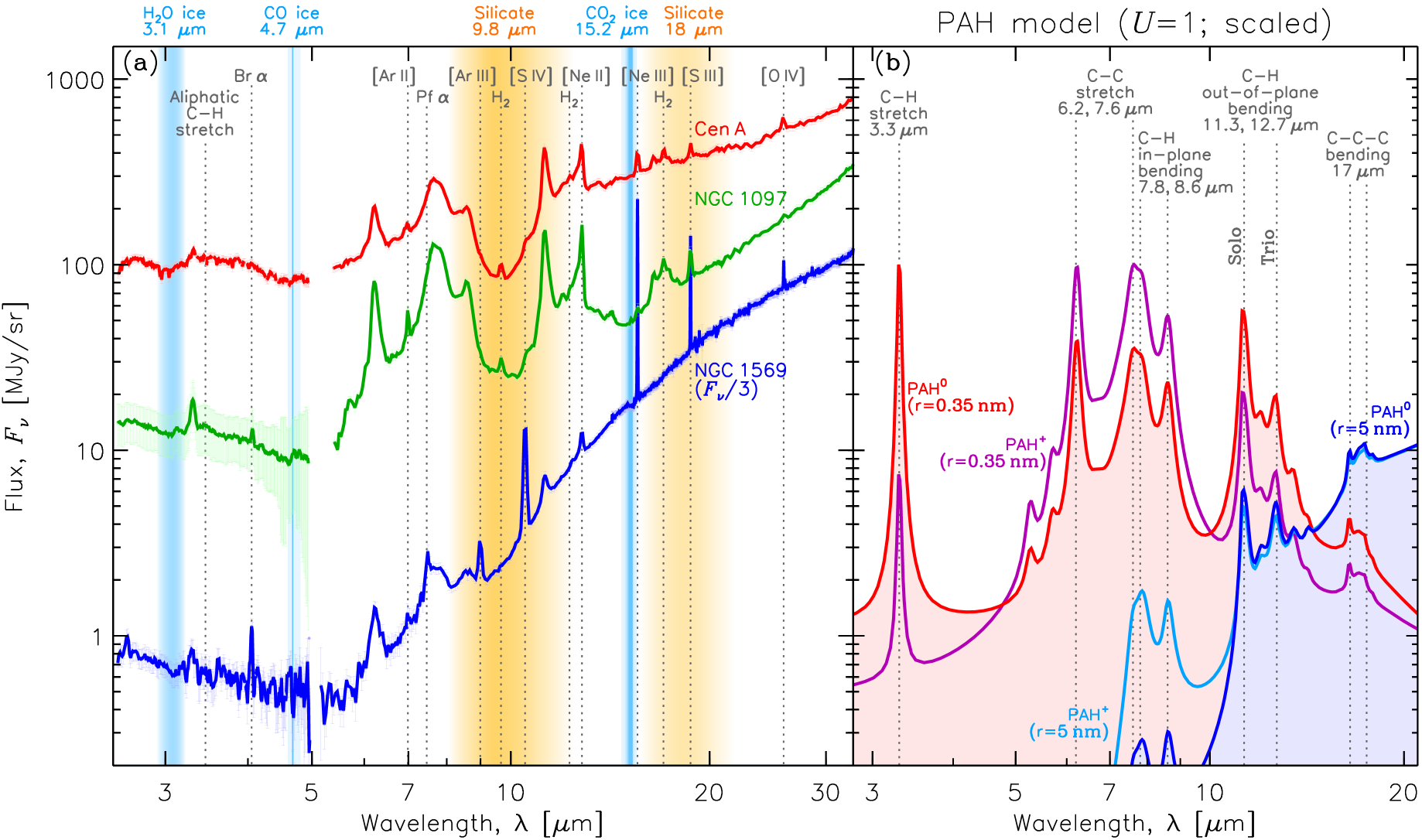

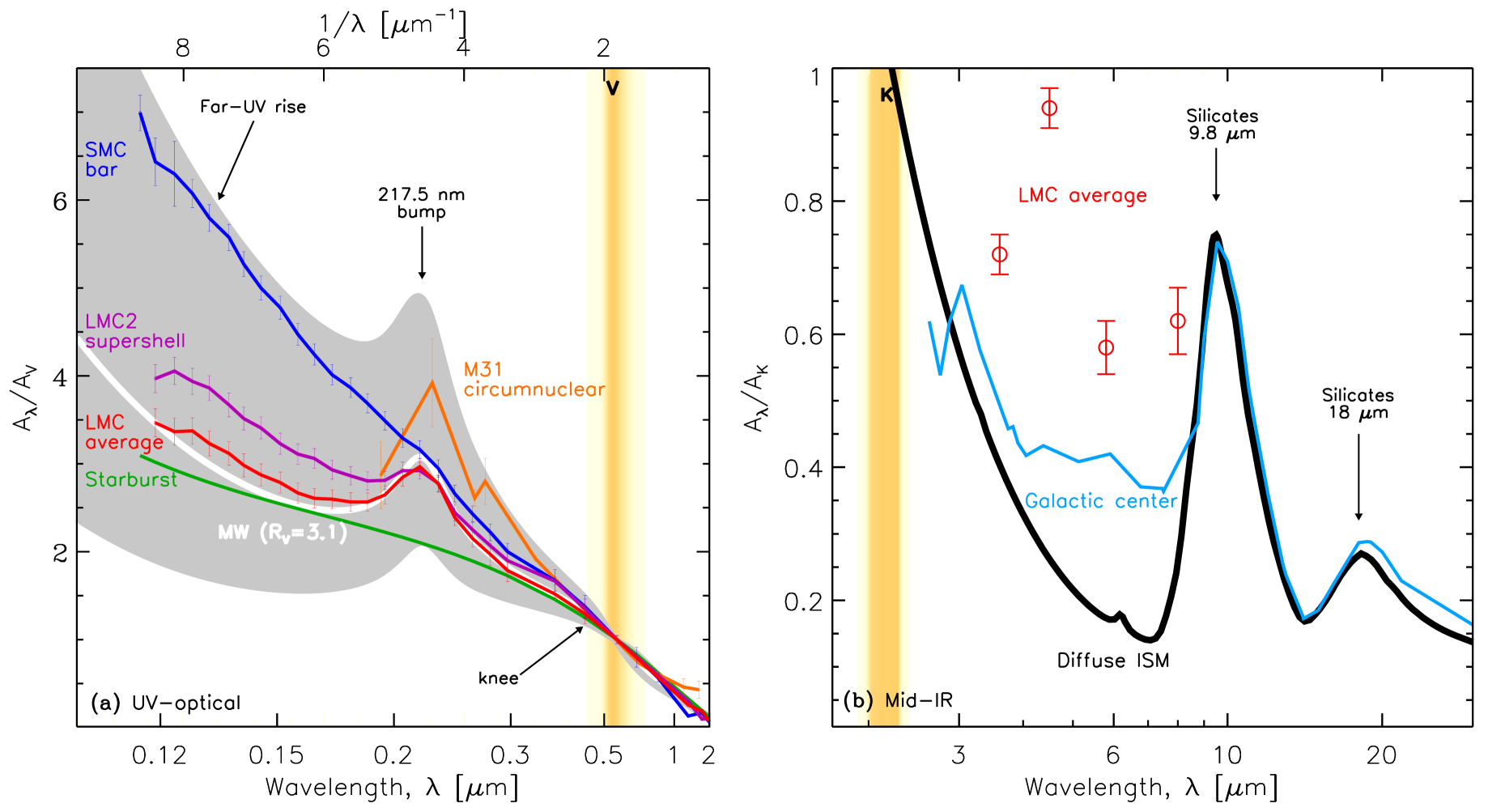

A grain mixture undergoing a given set of physical conditions will exhibit the following observables (represented on Figure 1): (1. Emission) the emission of a thermal continuum (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@8) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ to mm), and molecular and solid state features (Mid-\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@9) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ; \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Mid-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@10) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ); a possible microwave emission (cm); a possible luminescence (visible); the possible polarization of this emission (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@11) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ to mm); (2. Absorption) the absorption of the light from a background source by a continuum, as well as molecular and solid state features, including diffuse interstellar bands and ices (X-ray to \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Mid-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@12) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ); the possible polarization of this absorption (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[UV]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Ultraviolet\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@13) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ to visible); (3. Scattering) the scattering of the light from a bright source in our direction, and its polarization (X-ray to Near-\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@14) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ; \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[NIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Near-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@15) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ). (4. Depletions) some elemental depletion patterns.

2.1 The Invaluable Laboratories of Nearby Galaxies

Most of our knowledge of the dust properties comes from studies of the Milky Way (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MW]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Milky Way\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@24) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ). However, as it will be demonstrated in this paper, an increasing number of nearby galaxy studies provide unique discriminating constraints on fundamental dust processes. Indeed, nearby galaxies harbor a wider diversity of environmental conditions (metallicity, star formation activity, etc.) than what can be found in the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MW]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Milky Way\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@25) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ . In particular, they allow us to observe dust in extreme conditions. Second, they constitute a necessary intermediate step towards understanding distant galaxies, as they are spatially resolved and have a better wavelength coverage. Finally, the interpretation can sometimes be more difficult in the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MW]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Milky Way\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@26) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ , as we see the projected material of its entire disk. On the contrary, high latitude observations of face-on galaxies can provide cleaner sightlines.

We do not have a precise definition of nearby galaxies. They constitute a category expanding with the angular resolution of \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@27) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ observatories. In this review, we consider they are objects closer than Mpc.

3 THE MACROSCOPIC DISTRIBUTION OF DUST IN GALAXIES

3.1 The Observational Point of View

3.1.1 The Dust Distribution in Disk Galaxies

Dust biases our understanding of galactic structure, as it affects our derivation of luminosity profiles. The level of dust attenuation can indeed strongly vary depending on the sightline and from one galaxy to another (e.g. Calzetti, 2001; Pierini et al., 2004; Battisti, Calzetti & Chary, 2016). Understanding how dust is distributed in galaxies is a necessary step to correct for these attenuation effects. ††margin: \entry Scale-length/heightthe intensity, at radius/azimuth, , can be written as: , where is the scale-length/height.

3.1.1.1 MIR dust scale-length

@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISO]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared Space Telescope (5-210 microns; 1995-1998)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@28) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ observations helped assess the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Mid-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@29) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ extent of nearby spirals (especially at 7 and ). They showed that the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Mid-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@30) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ and optical emission have very similar morphologies and concentration indices (Boselli et al., 2003). However, the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Mid-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@31) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ scale-length tends to be systematically smaller than the optical one (Malhotra et al., 1996) and the arm/inter-arm contrast is larger in the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Mid-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@32) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ than in the optical (Vogler et al., 2005). From a large range of morphologies, Roussel et al. (2001) also found that if the IR-to-optical size ratio does not seem to be affected by the presence of a bar, this ratio is, on the contrary, particularly reduced in H i-deficient galaxies or early-type galaxies (see also Bendo et al., 2002). Numerous analysis have shown that the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Mid-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@33) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ disk has a similar scale-length to that of 12CO(10), H or the radio continuum (Sauvage et al., 1996; Walsh et al., 2002; Vogler et al., 2005). The relation with H, in particular, indicates that the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Mid-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@34) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ scale-length of a galaxy is determined by its star-forming activity. Indeed, the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Mid-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@35) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ emission is enhanced in star forming regions. With \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[Spitzer]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Spitzer space telescope (3-160 microns; 2003-2009)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@36) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ , the improved sensitivity and spatial resolution opened a new frame to model the distribution of dust inside galaxies and in particular to derive radial profiles. \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[Spitzer]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Spitzer space telescope (3-160 microns; 2003-2009)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@37) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ confirmed that the concentration index varies with wavelength. Studying radial profiles of 75 nearby galaxies, Muñoz-Mateos et al. (2009b) found that the concentration indices drop in the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[UIB]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Unidentified infrared band\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@38) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ s (5.8 and ; Section 6.1.2). The \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Mid-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@39) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ observations at longer wavelengths rather indicate a large variety of behaviours, including galaxies with very intense nuclear, circumnuclear or outer ring emission, thus larger concentration indices (e.g. NGC 1291, NGC 1512, NGC 1097, NGC 3351). ††margin: \entry ISOInfrared Space Observatory (; ) \entryConcentration indexratio between radii along the major axis encompassing 75 and of the total flux of a galaxy. \entrySpitzerspace telescope (; ). \entryUIBUnidentified Infrared Bands (cf. Section 6.1.2). Prominent \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Mid-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@40) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ features (Figure 1), attributed to carbonaceous grains.

3.1.1.2 FIR/submm dust scale-length

From \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISO]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared Space Telescope (5-210 microns; 1995-1998)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@41) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ observations, it quickly became clear that the disk scale-length of the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@42) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ emission increases with wavelength (Hippelein et al., 2003), with a Far-\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@43) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[FIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Far-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@44) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ) scale-length larger than the optical scale-length (Tuffs et al., 1996; Alton et al., 1998; Haas et al., 1998; Davies et al., 1999; Trewhella et al., 2000). This \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[FIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Far-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@45) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ colour gradient observed in the disk suggests that part of the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[FIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Far-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@46) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ emission arises from grains heated by the radially decreasing diffuse InterStellar Radiation Field (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISRF]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar radiation field\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@47) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ). In the edge-on spiral galaxy NGC 891, Popescu & Tuffs (2003) showed that large amounts of \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[FIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Far-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@48) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ emission was associated to the extended H i disk, raising the question of whether grains are transported from the inner/optical disk, transferred via interactions or more resistant to destruction by shocks in the outer disk. \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[Spitzer]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Spitzer space telescope (3-160 microns; 2003-2009)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@49) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ , \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[Herschel]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Herschel space observatory (55-672 microns; 2009-2013)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@50) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ , as well as plane or ground-based \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[submm]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Submillimeter\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@51) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ instruments have since then revolutionised our vision of the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[FIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Far-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@52) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ /\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[submm]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Submillimeter\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@53) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ emission and particularly confirm the detection of large cold extended disks (Block et al., 1994; Stevens, Amure & Gear, 2005; Hinz et al., 2012). In M 51, the scale-length of the underlying exponential disk was estimated as kpc (Meijerink et al., 2005). More statistically, Muñoz-Mateos et al. (2009a) and Hunt et al. (2015) examined the exponential dust profiles of nearby galaxies. They showed that the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[FIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Far-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@54) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ scale-length does not vary strongly with galaxy type and is on average larger than stellar scale-lengths. ††margin: \entry Herschelspace observatory (; ).

3.1.1.3 Scale-height Studies

In the Galaxy, a scale-height of the order of 100 pc has been estimated using \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IRAS]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared astronomical satellite (12-100 microns; 1983)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@55) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ observations at , with a vertical distribution that correlates with the distribution of the H i gas (Boulanger & Perault, 1988). Davies et al. (1997) extended the analysis to the colder dust phase using \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[COBE]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Cosmic Background Explorer (12-5000 microns; 1989-1993)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@56) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ data and found a more diffuse 20 K dust component, with a cold dust scale-height of about pc (Davies et al., 1997). Outside our \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MW]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Milky Way\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@57) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ , edge-on galaxies are ideal objects to constrain this parameter. Xilouris et al. (1999) studied the stellar and dust disks in five of these edge-on late-type spirals and found that their mean optical-to-dust scale-height ratio was . This ratio is often used as an a priori assumption for disk models (Tempel, Tamm & Tenjes, 2010). Quantifying the dust scale-height is undoubtedly more difficult for face-on galaxies. Padoan et al. (2001) proposed a new method to measure the average scale-height in face-on disk galaxies. From the H i data in the Large Magellanic Cloud (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[LMC]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Large Magellanic cloud\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@58) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ), they interpreted the break in the power-law shape of the spectral correlation function as the boundary of the gas mass distribution and velocity field. The method has been since then applied to derive scale-height estimates of the warm and cold dust. In the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[LMC]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Large Magellanic cloud\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@59) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ , Block et al. (2010) found that the break in the power spectrum is occurring on scales of pc in the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[FIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Far-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@60) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ . Combes et al. (2012) found similar scale-heights in M 33. The technique is limited by the resolution of the observations: artificial breaks can appear when the scale-height is too close to the resolution scale. Finally, radiative transfer codes are robust tools to model the absorption and re-emission by dust and derive structural parameters (cf. Section 3.2). The model of Baes et al. (2003), for instance, has been used to derive scale-lengths and scale-heights in edge-on galaxies (De Looze et al., 2012a; De Geyter et al., 2015; Viaene et al., 2015). The scale-heights derived in these studies typically range from to 200 pc.

3.1.2 The Dust Distribution in Irregular Galaxies

Irregular galaxies can contain large amounts of atomic gas that typically extend to twice their Holmberg radius (e.g. Huchtmeier, Seiradakis & Materne, 1981). They are also rich in dust, with very similar optical and \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Mid-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@61) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ scale lengths (Hunter, Elmegreen & Martin, 2006). The dust emission in irregular galaxies is clumpy and warm, with a hot dust and \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[UIB]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Unidentified infrared band\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@62) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ emission mostly observed towards bright H ii regions. This suggests that massive stars are a major source of heating in these environments (e.g. Hunter, Elmegreen & Martin, 2006).

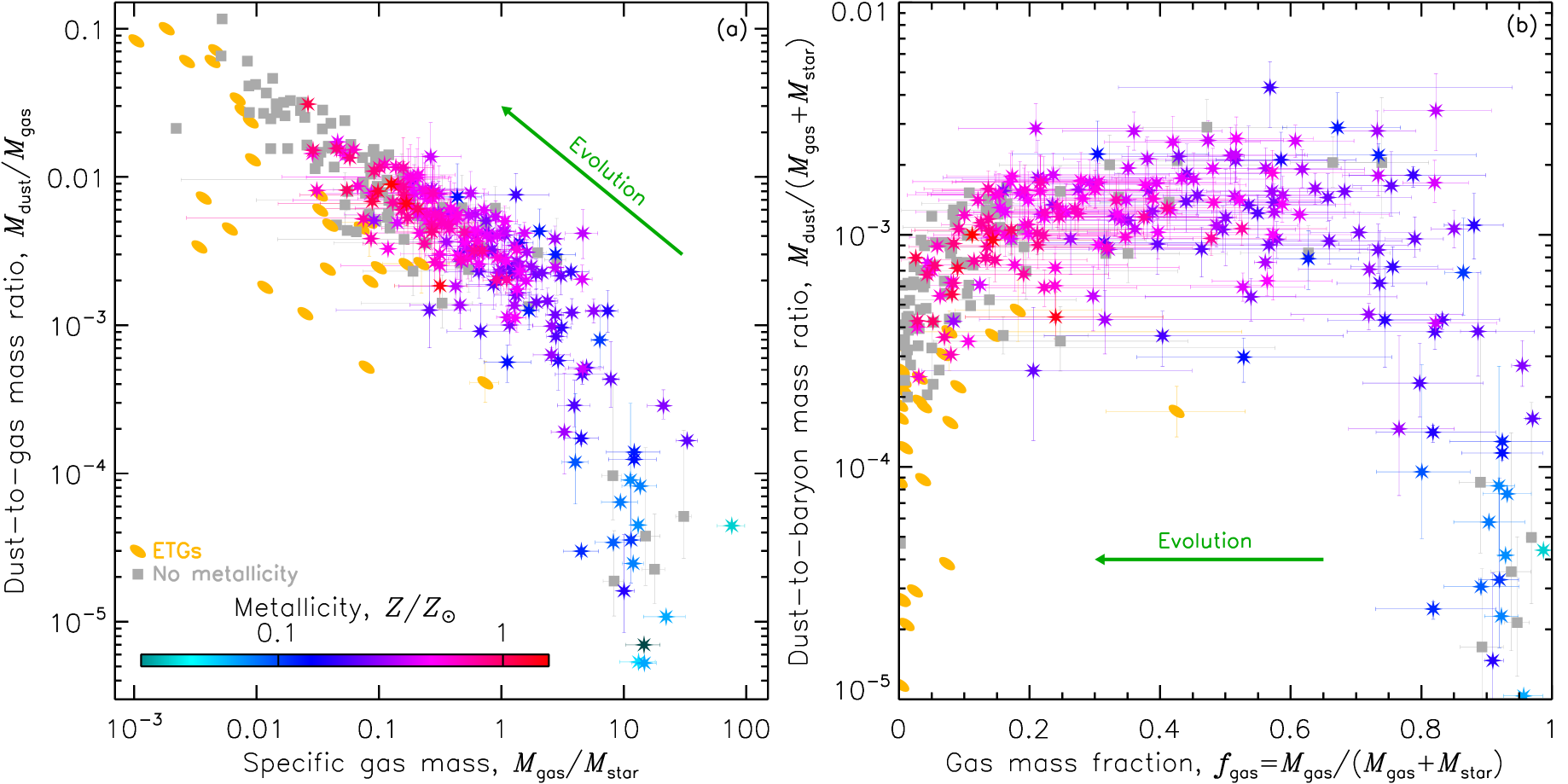

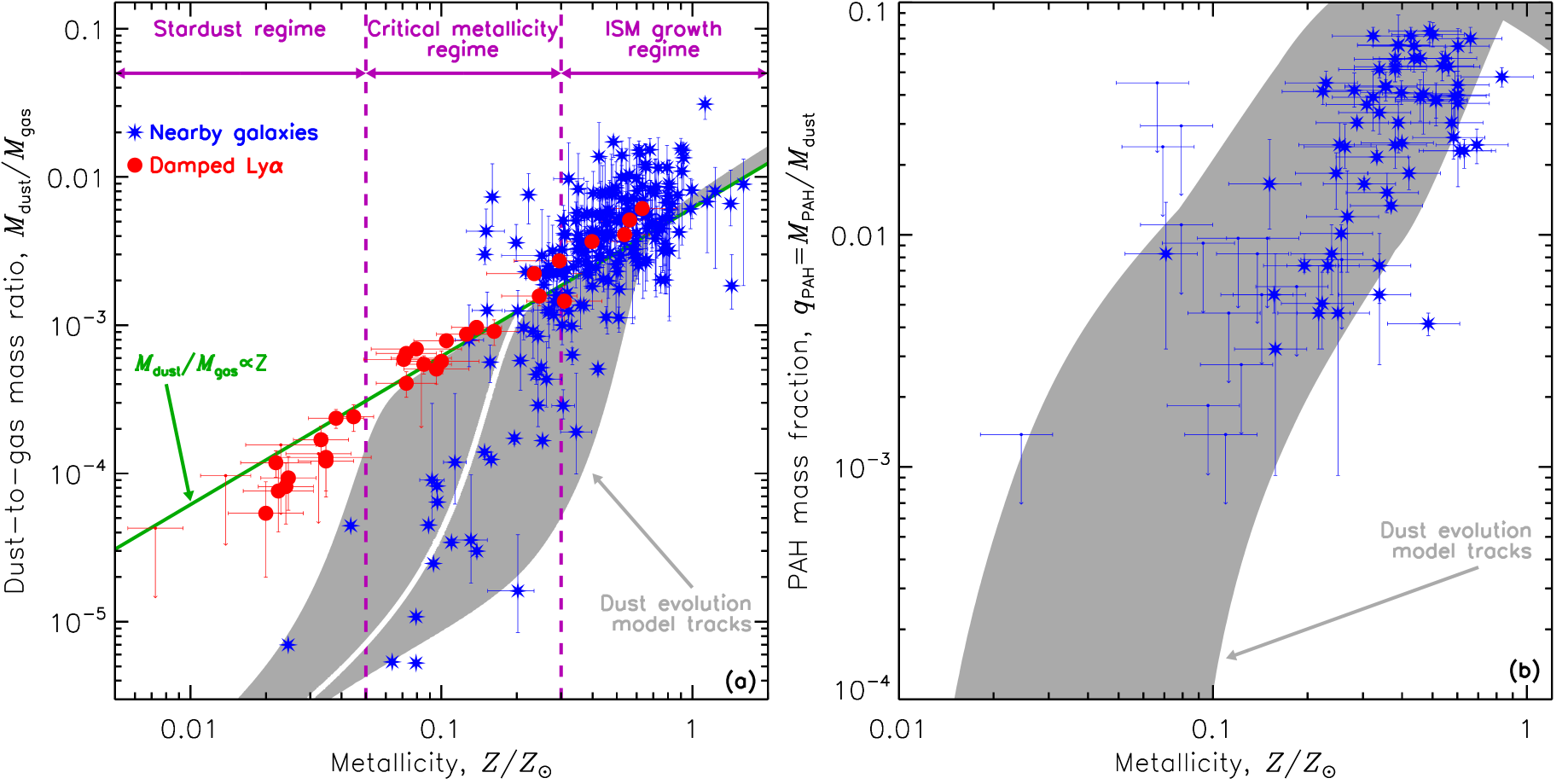

3.1.3 The Dust Distribution in Dwarf Galaxies

One of the main characteristics of dwarf galaxies is their low metallicity (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Metallicity\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@63) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ). As we will see in Section 9.3.2, the dust-to-gas ratio scales roughly with \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Metallicity\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@64) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ . The \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISM]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar medium\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@65) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ in these objects is less dusty and thus, more transparent. Similarly to irregular galaxies, massive stars are a major source of heating in these objects (e.g. Walter et al., 2007), and they are permeated by SuperNova (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[SN]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Supernova\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@66) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ )-triggered shock waves (e.g. Oey, 1996). Finally, these galaxies exhibit large H i envelopes. The \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@67) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ emitting region can correspond to only of the total mass of the system (e.g. Walter et al., 2007).

3.1.4 The Dust Distribution in Elliptical Galaxies

Elliptical galaxies possess very little dust: the average dust-to-stellar mass ratio is times lower than that of spiral galaxies (Smith et al., 2012). Dust-lanes are, however, commonly detected in elliptical galaxies (Sadler & Gerhard, 1985). Jura et al. (1987) for instance found that half of nearby ellipticals are detected at \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IRAS]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared astronomical satellite (12-100 microns; 1983)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@68) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ wavelengths. (Smith et al., 2012) found that the elliptical galaxies detected at tend to have higher X-ray luminosities. Their dust may be heated in part by electron collisions (Goudfrooij & de Jong, 1995). ††margin: \entry IRASInfraRed Astronomical Satellite (; 1983).

3.1.5 The Dust Distribution in Galactic Superwinds

Dust at high latitudes or in galactic haloes can be explained as resulting from various mechanisms, among which stellar feedback, transport via cosmic-ray driven winds or radiation pressure on the grains (Bocchio et al., 2016). The latter mechanism could also partly contribute to drive the galactic superwinds in star-forming galaxies even if several studies have shown that it is insufficient to be the only mechanism (Hopkins, Quataert & Murray, 2012; Contursi et al., 2013). Contursi et al. (2013) showed that, in the outflow of M 82, dust is slower than the ionized and molecular gas, indicating that dust grains are kinematically decoupled from the gas in the superwind. Most of this dust is not fast enough to escape and may fall back into the galaxy disk.

3.1.6 Dust Heating Sources Probed With Infrared Colours

Dust emits in the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@69) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ –\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[submm]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Submillimeter\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@70) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ . In this regime, the ratio of two fluxes (or colour) provides information on the grains, the same way optical colours provide information on the stars. These colours are widely used to understand the sources of heating of \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISM]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar medium\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@71) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ dust. From \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IRAS]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared astronomical satellite (12-100 microns; 1983)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@72) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ observations, Lonsdale Persson & Helou (1987) were among the first ones to use the correlation of the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 60 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@73) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ /\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 100 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@74) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ colour temperature with tracers of the old stars, to study their heating contribution. With \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[Spitzer]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Spitzer space telescope (3-160 microns; 2003-2009)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@75) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ observations, global \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 8 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@76) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ /\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 160 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@77) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ratios were then used to probe the origin of the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[UIB]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Unidentified infrared band\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@78) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ s (cf. Section 6.1.2) and to show that their emission correlates surprisingly well with that of the diffuse, cold dust (e.g. Bendo et al., 2008). Resolved observations later showed that enhancements in the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 8 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@79) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ /\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 160 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@80) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ratio are spatially offset relative to the star forming regions, suggesting that the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[UIB]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Unidentified infrared band\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@81) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ s could be partly excited by photons leaking out of star forming regions (Jones et al., 2015) by up to (Crocker et al., 2013). ††margin: \entry Monochromatic luminositywe note , the monochromatic luminosity (), at wavelength ().

With the arrival of \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[Herschel]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Herschel space observatory (55-672 microns; 2009-2013)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@82) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ , the study was pushed towards longer wavelengths, tracing dust at lower temperatures. \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[Herschel]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Herschel space observatory (55-672 microns; 2009-2013)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@83) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ratios have been extensively correlated with both stellar surface brightnesses and star formation rate tracers. These analyses usually find a strong correlation of the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 250 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@84) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ /\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 350 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@85) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ and \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 350 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@86) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ /\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 500 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@87) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ratios with the local stellar mass, showing the importance of the lower-mass stellar populations as a heating source of the coldest dust population (Bendo et al., 2010; Boquien et al., 2011). By correlating the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[submm]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Submillimeter\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@88) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ratios with a linear combination of tracers of the total stellar population () and of the star forming regions (H), Bendo et al. (2012) could segregate the two different heating sources and found that of the heating of cold dust is assured by lower-mass stars, in disk galaxies. Ratios at shorter wavelength, such as \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 70 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@89) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ /\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 160 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@90) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ or \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 160 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@91) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ /\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 250 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@92) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ , are less correlated with radius and more strongly correlated with the Star Formation Rate (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[SFR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Star formation rate\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@93) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ). Boselli et al. (2010) and Boquien et al. (2011) found similar results, showing in particular that the warm dust temperature as measured by the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 60 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@94) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ /\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 100 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@95) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ratio seems to increase with the birthrate parameter, , whereas the cold dust temperature, (measured by the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 350 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@96) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ /\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Monochromatic luminosity at 500 microns (Lsun/Hz)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@97) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ratio) seems to be anti-correlated with . However, the old stellar population probably continues to also play a role in the heating of the warm dust, with a contribution that seems to correlate with the galaxy evolutionary stage (for instance significant global contribution of the bulge stars in early-type galaxies like M 81; Bendo et al., 2012). On the other hand, Rémy-Ruyer et al. (2013) showed a trend of colour temperature with metallicity, suggesting that low-\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Metallicity\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@98) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ systems are on average hotter (see also Melisse & Israel, 1994). This is conjectured to be due to the enhanced contribution of young star heating at low-\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Metallicity\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@99) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ . ††margin: \entry Birth rate parametercurrent \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[SFR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Star formation rate\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@100) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ divided by the mean \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[SFR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Star formation rate\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@101) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ over the lifetime of the galaxy.

New results from radiative transfer models (cf. Section 3.2) are now quantifying better the respective contributions of the different stellar populations to dust heating. In M 31, Viaene et al. (2017) showed that of the dust could be heated by the lower-mass stellar populations (see their Fig. 8). Further detailed analysis would be necessary to quantify more robustly the contribution as a function of the galaxy type.

3.2 The Radiative Transfer Approach

[h]

4 WHAT ARE THE SPATIAL SCALES RELEVANT TO DUST HEATING?

The dust physical conditions vary on spatial scales of the order of the mean free path of a \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[-band]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (560 nm\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@102) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ photon:

| (1) |

For a diffuse region (), pc, while for a dense region (), pc. Thus, to resolve dust temperature variations, in an edge-on cloud, we would need to resolve structures of pc, which translates into for the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[LMC]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Large Magellanic cloud\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@103) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ (typical \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ALMA]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Atacama large millimeter array (300 microns-1 cm; 2011)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@104) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ & \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[JWST]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (James Webb Space Telescope (0.6-27 microns; 2018-)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@105) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ resolution) and in M 31 (currently inaccessible). For a face-on cloud, there will be mixing along the line of sight, in any case.

4.0.1 Radiative Transfer Models

The most rigorous way to understand the effects of dust extinction and emission on \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[UV]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Ultraviolet\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@106) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ -to-mm observations of galaxies is to model the Radiative Transfer (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[RT]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Radiative transfer\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@107) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ) of the starlight through their dusty \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISM]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar medium\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@108) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ , in a realistic 3D geometry. Several teams have developed such codes for disk galaxies (e.g. Baes et al., 2003; Bianchi, 2008; Popescu et al., 2011). These codes solve the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[RT]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Radiative transfer\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@109) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ equation, accounting for multiple anisotropic scattering, absorption, and dust and stellar emission. This type of computation is numerically intensive. Most models implement a Monte Carlo method, with various refinements and heavy parallelization.

4.0.2 Application to Galaxies

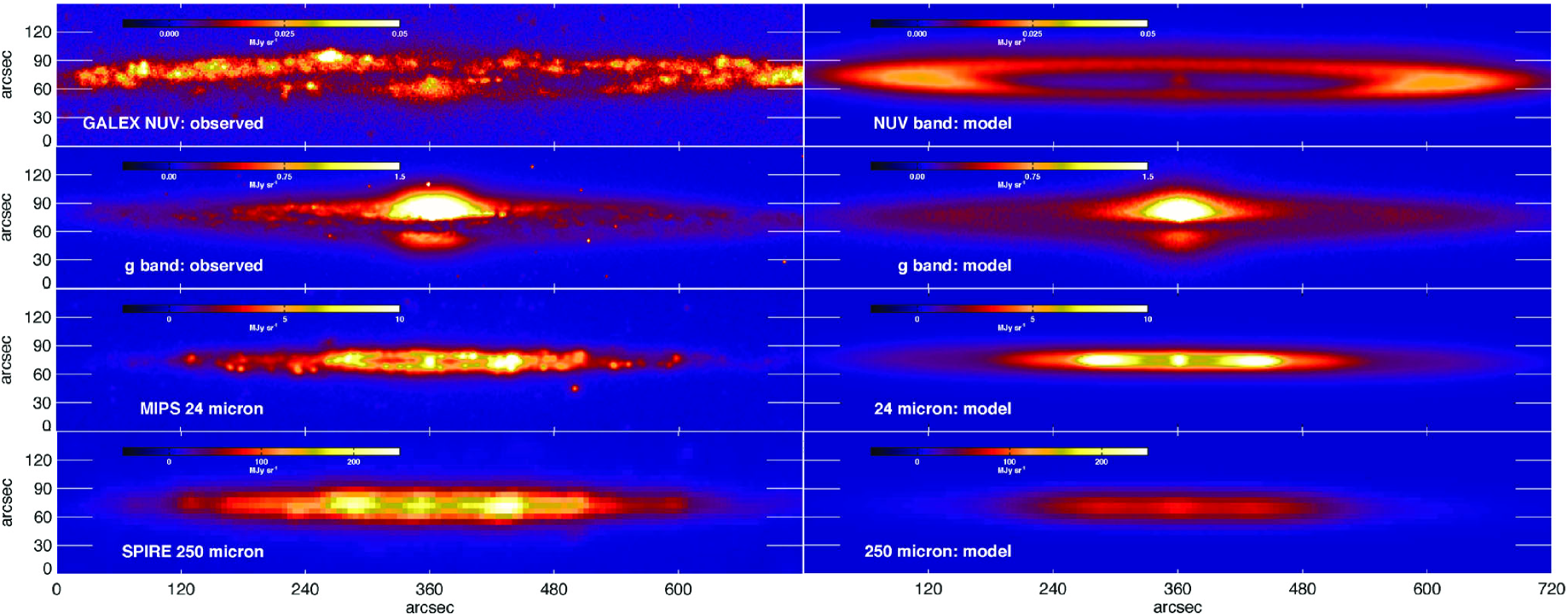

Applying 3D \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[RT]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Radiative transfer\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@112) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ models to reproduce the spatial flux distribution of galaxies, in all wavebands, is not straightforward. Indeed, the observations provide only 2D projected constraints. This is why most studies favor edge-on galaxies, as the images of such objects provide constraints on both the radial and azimuthal distributions, assuming axisymmetry (Figure 2). Several studies have modelled the effect of extinction on the optical data of disk galaxies using such codes (e.g. Xilouris et al., 1999; Alton et al., 2004; Bianchi, 2007). They were able to answer the recurring question about the optical thickness of disk galaxies (Disney, Davies & Phillipps, 1989). In particular, Xilouris et al. (1999) found that the face-on optical depth of typical spiral galaxies is less than one in all optical bands. These studies also provide a more comprehensive answer to the nature of the dust heating sources and on the scale-length and scale-height (cf. Sections 3.1.6 and 3.1.1.3). Finally, these models account for the energy balance between the escaping \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[UV]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Ultraviolet\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@113) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ -visible light and the re-emitted \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@114) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ -\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[submm]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Submillimeter\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@115) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ radiation. Interestingly enough, several studies report a deficit of modelled \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[FIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Far-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@116) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ emission by a factor , compared to the observations (Alton et al., 2000, 2004; Dasyra et al., 2005; De Looze et al., 2012a, b). This discrepancy is thought to reside in a lack of details in modelling the geometry. In particular, the presence of young stars, deeply embedded in molecular clouds, could compensate this deficit without significantly altering the extinction (e.g. Baes et al., 2010).

4.1 Phenomenological SED Modelling

4.1.1 The Mixing of Physical Conditions

Radiative transfer is impractical in most cases, as the geometry of the source is often poorly known. In addition, radiative transfer models of whole galaxies do not resolve spatial scales small enough (Equation 1). Hence, we are usually compelled to make approximations about the complex topology of the studied object.

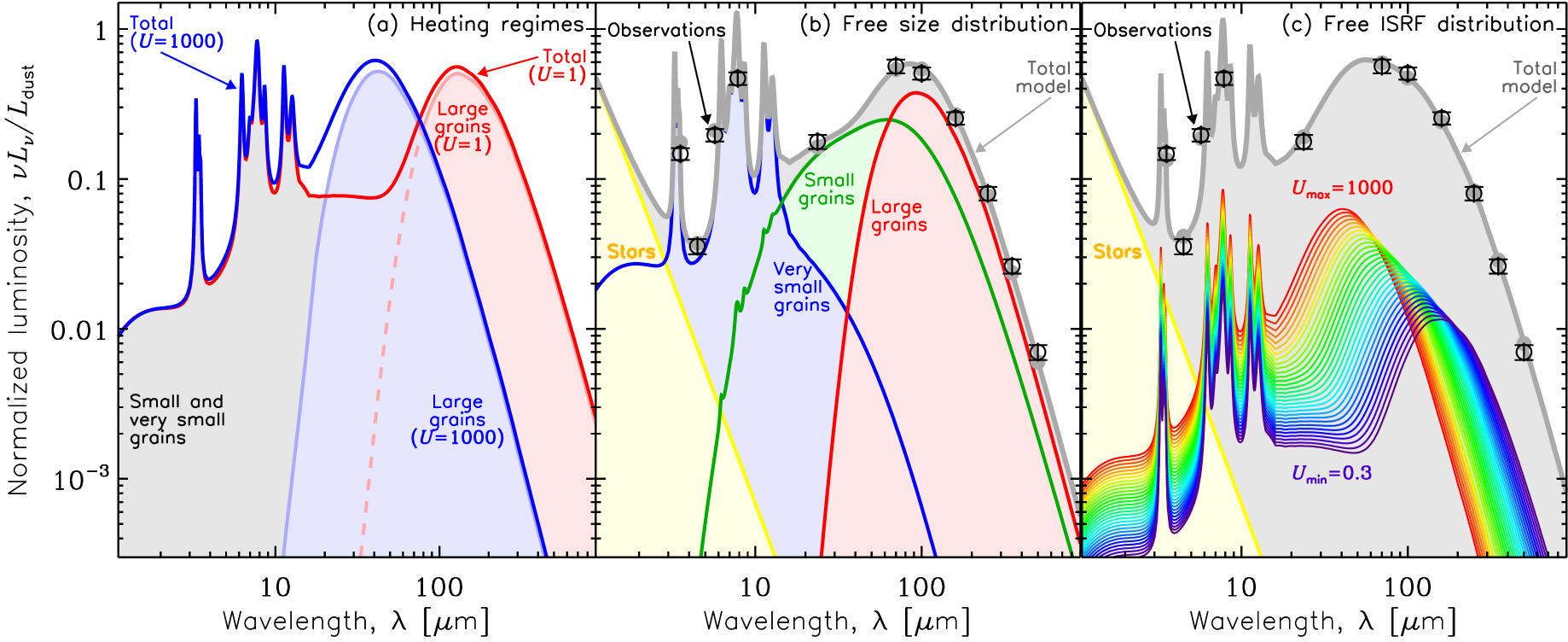

4.1.1.1 The Isothermal approximation

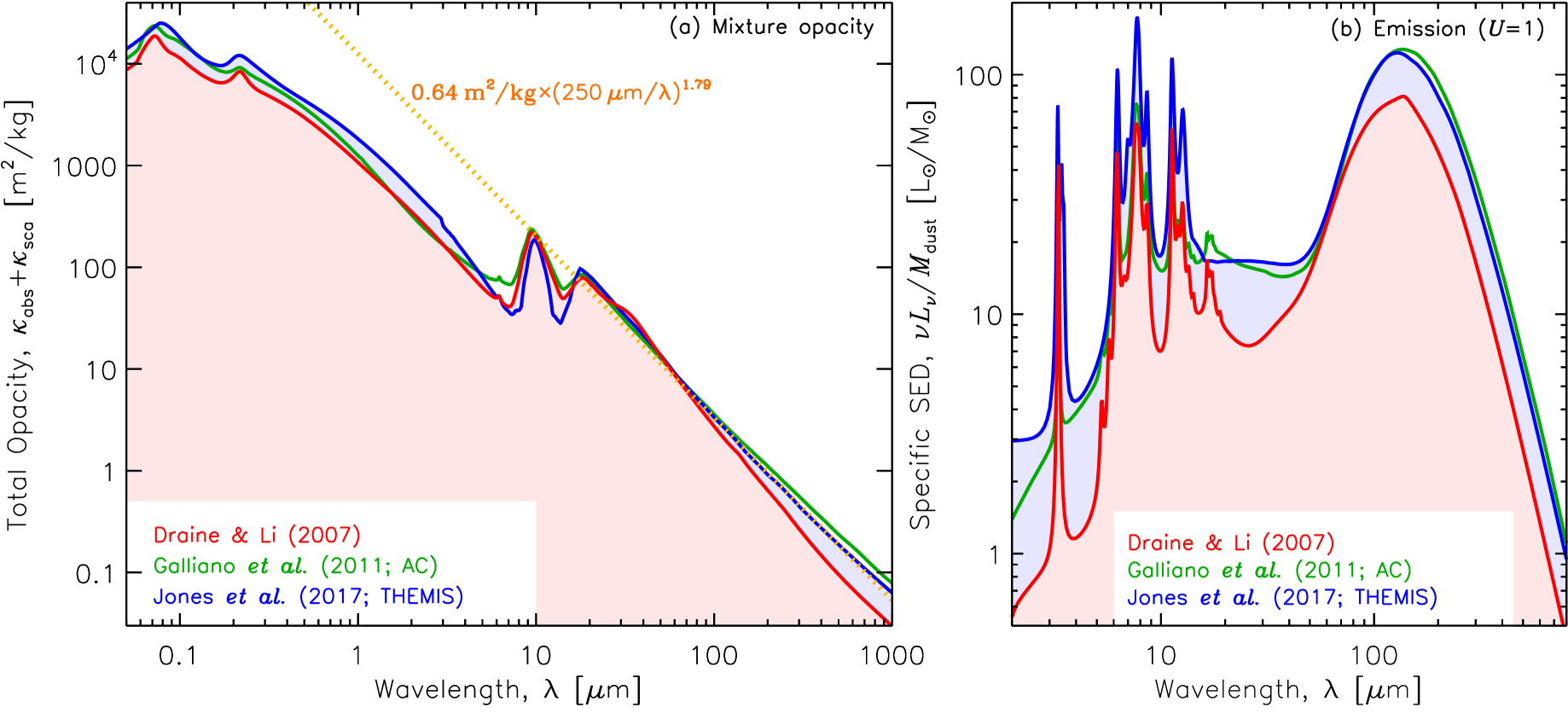

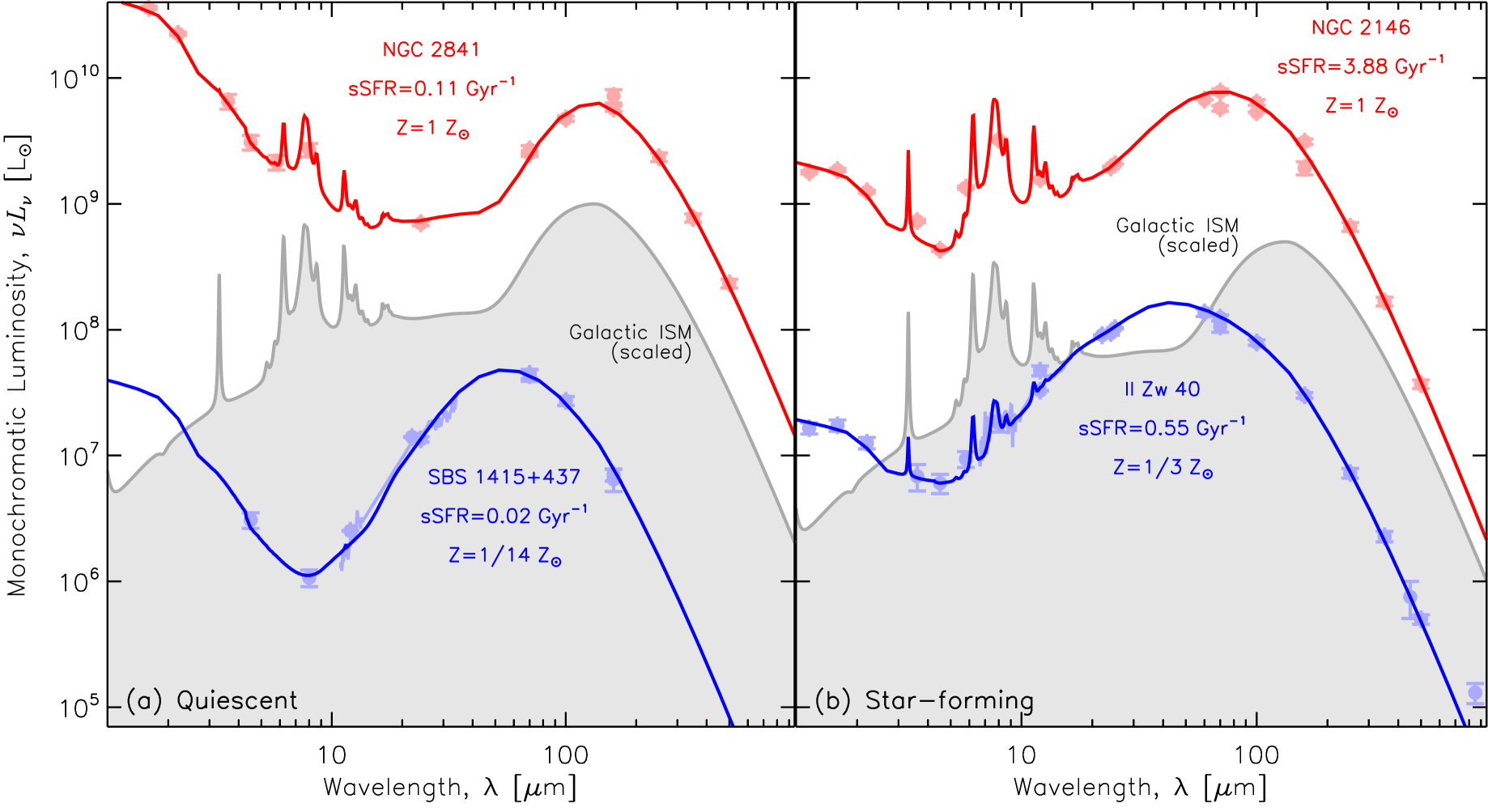

To first order, one can ignore the variations of the physical conditions. The Modified Black Body (\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MBB]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Modified black body\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@117) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ), the most widely used approximation, assumes that the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[IR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@118) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ emission comes from identical grains, at a single temperature, , with a power-law, wavelength-dependent, dust mass absorption coefficient, or opacity:

| (2) |

In principle, a fit of this model, varying , and \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Emissivity index (power-law index of a modified black body)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@119) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ , provides constraints both on the grain physical conditions (through ), and on their composition (through \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Emissivity index (power-law index of a modified black body)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@120) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ ). Indeed, different materials can have different \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Emissivity index (power-law index of a modified black body)\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@121) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ . An inverse relation is also observed on some laboratory analogs (e.g. Mennella et al., 1998; Boudet et al., 2005). However, a gradient of temperature tends to broaden the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[SED]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Spectral energy distribution\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@122) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ . The inherent mixing of physical conditions is thus enough to bias these estimates (e.g. Juvela & Ysard, 2012; Hunt et al., 2015). In addition, the contribution from out-of-equilibrium grains can be non negligible at (Figure 3-a). In that sense, the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MBB]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Modified black body\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@123) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ derived parameters are ambiguous effective quantities (, ), which can be reliably interpreted in terms of intrinsic grain properties only: (1) in diffuse regions, where the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISRF]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar radiation field\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@124) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ is expected to be roughly uniform, or in cold cores; and (2) provided that the fit is constrained at long enough wavelengths (). ††margin: \entry ISRF intensity\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar radiation field intensity\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@125) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ is the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISRF]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar radiation field\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@126) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ intensity, integrated in . It is normalized so that in the solar neighborhood.

Alternatively, one can also fit an observed \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[SED]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Spectral energy distribution\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@127) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ , with a full dust mixture (such as in Figure 3-a), varying the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISRF]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar radiation field\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@128) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ intensity, \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar radiation field intensity\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@129) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ , and the mass of each sub-components (Figure 3-b). With such an approach, the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Mid-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@130) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ wavelengths can be interpreted in terms of size distribution variations, provided that the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISRF]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar radiation field\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@131) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ is roughly uniform.

[h]

5 DUST HEATING REGIMES: EQUILIBRIUM OR STOCHASTIC?

5.0.1 Thermal Equilibrium

The enthalpy, , of grains with large enough radii () is, in most cases, significantly higher than the mean energy of the incident photons they absorb, . Therefore, a single photon event does not notably modify their temperature. They are at equilibrium with the radiation field. Their spectrum is proportional to a Planck function times a wavelength-dependent opacity (Figure 3-a).

5.0.2 Stochastic Heating

On the opposite, for small grains (), . A single photon event will cause temperature spikes at a few hundred K (depending on its size), followed by a significant cooling before the next absorption (Draine & Anderson, 1985). These temperature fluctuations result in a broad spectrum, extending down to the MIR (Figure 3-a). Such grains are out of thermal equilibrium.

5.0.2.1 Distributions of starlight intensities

It is possible to empirically account for the mixing of physical conditions, by parameterizing the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISRF]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar radiation field\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@148) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ intensity distribution. One of the most useful prescriptions is given by Dale et al. (2001). It assumes that the dust mass in different bins of \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar radiation field intensity\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@149) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ follows a power-law: for . This way, varying the parameters , and , an observed \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[SED]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Spectral energy distribution\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@150) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ can be fit with a combination of physical conditions. This is demonstrated in Figure 3-c. One of the limitations of this approach is that it ignores the variations of the grain properties with environments. As will be discussed in Section 9.2, the carriers of the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[UIB]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Unidentified infrared band\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@151) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ s are usually destroyed in regions of high \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar radiation field intensity\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@152) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ . The \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[FIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Far-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@153) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ emissivity will also change due to mantle processing and evaporation (cf. Section 9.2.1). In addition, there is a degeneracy between the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISRF]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar radiation field\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@154) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ distribution and the fraction of small grains. This is demonstrated in panels b and c of Figure 3. The same \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[SED]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Spectral energy distribution\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@155) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ is fitted either with an isothermal model, accounting for the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MIR]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Mid-infrared\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@156) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ fluxes by raising the fraction of small grains (b); or by adding hotter regions (c). Fortunately, the dust mass is dominated by the coldest large grains, and can thus be reasonably derived with this type of model. This type of model is superior to \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[MBB]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Modified black body\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@157) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ , as the latter underestimates the mass by in rather diffuse regions, and down to a factor of , where there is a lot of mixing (e.g. Galliano et al., 2011; Galametz et al., 2012; Rémy-Ruyer et al., 2015).

More complex parameterizations of the \HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@color\pc@hyenc@colorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@fontcolor\pc@hyenc@fontcolorpdfcommentcolor\HyColor@XZeroOneThreeFour\pc@goptd@icolor\pc@hyenc@icolorpdfcommentcolor\pdfmark[ISRF]pdfmark=/ANN,Subtype=/Widget,Raw=/TU (Interstellar radiation field\textCR(\pc@goptd@deadline)) /T (tooltip zref@158) /C [ ] /FT/Btn /F 768 /Ff 65536 /H/N /BS ¡¡ /W 0 ¿¿ distribution are possible (e.g. DL07, ). It is also possible to build multi-component models, where the phase composition is linked to the star formation history (e.g. da Cunha, Charlot & Elbaz, 2008).

5.0.2.2 A Matriochka effect