Torus actions whose equivariant cohomology is Cohen-Macaulay

Abstract.

We study Cohen-Macaulay actions, a class of torus actions on manifolds, possibly without fixed points, which generalizes and has analogous properties as equivariantly formal actions. Their equivariant cohomology algebras are computable in the sense that a Chang-Skjelbred Lemma, and its stronger version, the exactness of an Atiyah-Bredon sequence, hold. The main difference is that the fixed point set is replaced by the union of lowest dimensional orbits. We find sufficient conditions for the Cohen-Macaulay property such as the existence of an invariant Morse-Bott function whose critical set is the union of lowest dimensional orbits, or open-face-acyclicity of the orbit space. Specializing to the case of torus manifolds, i.e., -dimensional orientable compact manifolds acted on by -dimensional tori, the latter is similar to a result of Masuda and Panov, and the converse of the result of Bredon that equivariantly formal torus manifolds are open-face-acyclic.

1991 Mathematics Subject Classification:

Primary 55N25, Secondary 57S15, 57R911. Introduction

In the theory of equivariant cohomology, the class of equivariantly formal actions of a real torus on a compact manifold is certainly one of the most intensely studied. On the one hand, it comprises many important examples, such as Hamiltonian torus actions on compact symplectic manifolds, and on the other hand such actions have many beautiful properties, e.g. the equivariant cohomology is determined by the 1-skeleton of the action as proven by Chang and Skjelbred [ChSk 1974, Lemma 2.3], and thereby explicitly computable [GKM 1998, Theorem 1.2.2] via what is nowadays called GKM theory, see e.g. [GuZa 2001]. To our knowledge, the only known big classes of actions on manifolds for which the (-algebra structure of the) equivariant cohomology is explicitly computable are either equivariantly formal or have only one isotropy type.

A geometric property of equivariantly formal actions is that their minimal strata consist of fixed points. The fixed point set of an action plays an important role in the whole theory, as shown by e.g. the famous localization theorems. A basic example of its relevance is that it encodes the rank of as a module over .

The motivating question for our work was the following: Is there a suitable generalization of equivariant formality that also covers actions without fixed points?

From the point of view of computability of , the answer to this question is implicit in the proof of the exactness of the so-called Atiyah-Bredon sequence [Bre 1974] (Theorem 4.4, see also [FrPu 2003]), which can be regarded as an extension of the Chang-Skjelbred Lemma; the relevant property of for the proof is not that it is a free module, but that it is a Cohen-Macaulay module of Krull dimension .

In Section 6 we give the

Definition.

The -action is Cohen-Macaulay if is a Cohen-Macaulay module over .

The Cohen-Macaulay property was used as a tool in various papers on equivariant cohomology. The purpose of this work is to justify why it is the appropriate notion for answering the above question. The central role of the fixed point set will be seen to be assumed by the union of lowest dimensional orbits.

Let be the smallest occuring orbit dimension. Similarly to the equivariantly formal case [Bre 1974, FrPu 2007], there is an Atiyah-Bredon sequence, but with the fixed point set replaced by the union of -dimensional orbits, whose exactness is equivalent to Cohen-Macaulayness (Theorem 6.2):

Theorem.

The -action on is Cohen-Macaulay if and only if the sequence

is exact.

The notion of Cohen-Macaulay action encompasses both equivariantly formal actions and actions with only one isotropy type, including locally free actions. Namely, if the action is equivariantly formal, i.e., is a free module, is Cohen-Macaulay of maximal Krull dimension , and if the action is locally free it is Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension . Effective cohomogeneity-one actions are examples of Cohen-Macaulay actions of Krull dimension , see Example 6.5. To show that there are many more interesting examples of Cohen-Macaulay actions, we relax well-known sufficient conditions for equivariant formality in a way that we retain the Cohen-Macaulay property: (Theorem 7.1)

Theorem.

If the action admits a -invariant Morse-Bott function with critical set , then the action is Cohen-Macaulay.

and (Theorem 8.1)

Theorem.

If the -manifold admits a -invariant disk bundle decomposition satisfying the properties of Theorem 8.1, then the action is Cohen-Macaulay.

In every case, the philosophy is to replace the fixed point set by the union of lowest dimensional orbits.

The second half of the paper is dedicated to the question whether it is possible to give conditions on the orbit space of the action that imply that the action is Cohen-Macaulay. In Section 9, we prove an algebraic characterization of injectivity of the restriction map , where is the bottom stratum of the action, i.e., the union of the minimal strata. This yields as a corollary the geometric statement (Theorem 9.6)

Theorem.

If the orbit space of the -action is almost open-face-acyclic, then is injective.

Masuda and Panov [MaPa 2006] proved that a torus manifold, i.e., an orientable compact -dimensional manifold with fixed points, is equivariantly formal with respect to -coefficients if and only if it is locally standard and its orbit space is closed-face-acyclic. In Section 10 we show (Corollary 10.7, Theorem 10.24)

Theorem.

If acts effectively on an orientable compact manifold with open-face-acyclic orbit space, then and the action is Cohen-Macaulay.

Here is the lowest occuring orbit dimension. To a large extent, our proof uses the ideas of Masuda and Panov; however, there are several differences: Most importantly, several special features such as the so-called canonical models [MaPa 2006, Section 4.2], see Davis and Januszkiewicz [DaJa 1991, Section 1.5], or the equivalent characterization of equivariant formality via , are not available in our setting. Our chain of arguments instead relies on the fact that equivariant injectivity holds a priori by the results in Section 9, and various other modifications.

Our result states that actions on -dimensional orientable compact manifolds with open-face-acyclic orbit space are equivariantly formal. The converse of this statement was proven by Bredon [Bre 1974, Corollary 3]; we therefore obtain (Theorem 10.25):

Theorem.

A -action on an orientable compact manifold with is equivariantly formal if and only if its orbit space is open-face-acyclic.

Acknowledgements. We are grateful to Sönke Rollenske for various discussions on Cohen-Macaulay modules, and useful comments on a preliminary version of this paper. We wish to thank Matthias Franz and Volker Puppe for bringing to our attention Proposition 5.1 of their paper [FrPu 2003] and the important connection between Cohen-Macaulay and equivariantly formal actions described in Remark 6.3. These two points were independently noticed by the referee, whom we thank for his careful reading resulting in several improvements of the paper.

2. Preliminaries

Throughout this paper, will denote an -dimensional real torus. We will use several cohomology theories, always with as coefficient ring. All of them are defined for arbitrary (-)spaces, but have an equivalent description in the case of a differentiable manifold (with a differentiable -action). denotes singular (or deRham) cohomology. For a -space , denotes equivariant cohomology of the -action, i.e., the cohomology of the Borel construction [BBFMP 1960, Hsi 1975]. In the differentiable case this coincides with equivariant de Rham cohomology, see e.g. [GuSt 1999]. We will use the Cartan model , where is the symmetric algebra on the dual of the Lie algebra of , consists of the -invariant differential forms on , and is the equivariant differential.

Given a -action on an arbitrary space , the basic cohomology will be understood as the singular cohomology of the quotient . In the differentiable case this coincides with the usual definition of basic cohomology [Mic 2008, Theorem 30.36]: a differential form is basic if it is horizontal, i.e., the contractions with the -fundamental vector fields vanish, and -invariant. Then , where is the complex of basic forms, with the restriction of the usual differential.

The projection naturally induces a map

| (2.1) |

which in the differentiable case can also be seen to be induced by the inclusion of complexes . Note that in general (2.1) is not injective, see e.g. [GGK 2002, Example C.18].

There are also relative and compactly supported versions of equivariant and basic cohomology, where the latter will be denoted by an additional index, e.g. for compactly supported equivariant cohomology [GuSt 1999, Section 11.1].

In case acts locally freely on an orientable manifold , then is an orientable orbifold and hence [Sat 1956] there is Poincaré duality for basic cohomology: .

For a -action on a manifold and any subspace , let be the common zero set of all fundamental vector fields induced by . In other words, is the fixed point set of the action of the connected Lie subgroup of with Lie algebra . For , let be the connected component of that contains . A point is regular if its isotropy algebra is minimal among all isotropy algebras, and nonregular points are called singular. The regular set of the -action on is denoted , and the singular set . The respective regular and singular sets of the -action on are and . The are partially ordered by inclusion. The minimal elements with respect to this ordering are exactly those with . By definition, the bottom stratum of the action is the union of those minimal elements:

(Strictly speaking, one should refer to as the infinitesimal bottom stratum, as for the definition of regularity of a point we only consider its isotropy algebra instead of its isotropy group.) The set of fixed points is contained in .

For , let be the union of orbits of dimension . Clearly,

Furthermore, we define to be the union of orbits of dimension equal to . The are disjoint unions of submanifolds of type . In general, is not a submanifold of , but still it is an equivariant strong deformation retract of some neighborhood in (or ). Of importance will be the cohomology of the pair . For later use, we note that

and

3. General lemmata

In this section, we collect some more or less well-known lemmata on equivariant cohomology. If is a finitely generated graded -module, we define the support of as in [GuSt 1999, Section 11.3] to be the set of complex zeroes of the annihilator ideal of :

Because is graded, the annihilator ideal is a graded ideal, and is a conic subvariety of , i.e., for and we have . For an element , we define the support of to be the support of the submodule of generated by : . Clearly, for every we have .

Lemma 3.1.

Let a torus act on a manifold . If is any (not necessarily closed) Lie subgroup that acts trivially on and a subtorus of such that , then

as an -algebra.

Proof.

We have The equivariant differential leaves the space invariant and is zero on . Thus, ∎

Lemma 3.2.

Let act on a compact manifold and be any subspace. Then the kernel of the restriction map is given by .

Proof.

Note that is a closed -invariant submanifold of . By [GuSt 1999, Theorem 11.4.2] the kernel of the restriction map has support in the union of those subalgebras that occur as isotropy algebras in , i.e.

Thus, . Since for any , we have , we obtain .

Conversely, let and choose a subtorus such that . Then, by the previous lemma, so . ∎

Proposition 3.3.

Let a torus act on a manifold . Then the following properties are equivalent:

-

(1)

The action is locally free.

-

(2)

for large .

-

(3)

.

-

(4)

The support of is .

Proof.

We show . If the action is locally free, (this is standard for free actions, but also true for only locally free actions because we are using real coefficients, see e.g. Section C.2 of [GGK 2002]), so implies .

Assuming , there is some such that any closed equivariant differential form of degree at least is exact. Thus, writing , it follows that for any some power of annihilates . Therefore the common zero set of the polynomials that annihilate consists only of the element , hence .

It is clear that implies , so it remains to show that implies . Clearly, the complexification of every isotropy algebra is contained in the support of , because is not in the kernel of . Thus, if the support of is , the action is locally free. ∎

4. Equivariant formality

The -action on is equivariantly formal in the sense of [GKM 1998] if the cohomology spectral sequence associated with the fibration collapses at . The following are well-known equivalent characterizations of equivariant formality:

-

(1)

is free as an -module [AlPu 1993, Corollary 4.2.3].

-

(2)

[Hsi 1975, Corollary IV.2]. The inequality is true for any -action.

An important sufficient condition for equivariant formality is , see [GuSt 1999, Theorem 6.5.3].

Also the following proposition is fairly standard. One way to prove it is as an application of characterization (2) above, see e.g. the proof of the Main Lemma in [Bre 1974]; a proof using (1) is given in [Bri 2000, Lemma 2].

Proposition 4.1.

If the -action on is equivariantly formal, then for any subtorus , the -action on is equivariantly formal.

The next lemma can be proven as a direct application of characterization (2) above.

Lemma 4.2.

A -action on is equivariantly formal if and only if the -action on each connected component of is equivariantly formal.

The following corollary appears (with a different proof) as Theorem 11.6.1 in [GuSt 1999], and as Proposition C.28 in [GGK 2002].

Corollary 4.3.

If the -action on is equivariantly formal and is any subtorus, each connected component of contains a -fixed point. In other words: the bottom stratum of an equivariantly formal action is equal to the set of fixed points.

Proof.

The relevance of the notion of equivariant formality emerges from the fact that the equivariant cohomology of spaces satisfying this condition is (relatively) easy to compute, thanks to the exact sequence

Here, is the boundary operator in the long exact sequence of the pair . Injectivity of follows because the kernel of this map is the module of torsion elements [GuSt 1999, Theorem 11.4.4] and is torsion-free111This condition is not equivalent to equivariant formality; see [FrPu 2008] for an example.. Exactness at is the so-called Chang-Skjelbred Lemma [ChSk 1974, Lemma 2.3], see also [GuSt 1999, Section 11.5].

The following characterization of equivariant formality is an extension of the exact sequence above.

Theorem 4.4 ([Bre 1974], [FrPu 2007]).

The -action on is equivariantly formal if and only if the sequence

is exact.

In this sequence, the maps are the boundary operators of the triples . Exactness of the sequence under the condition of equivariant formality was proven by Bredon [Bre 1974, Main Lemma], adapting an analogous result of Atiyah in equivariant -theory [Ati 1974, Lecture 7]. Following Franz and Puppe, we will therefore refer to this sequence as the Atiyah-Bredon sequence. The converse direction is due to Franz and Puppe [FrPu 2007, Theorem 1.1]. Note that because we are using real coefficients we do not need any assumptions on the connectedness of isotropy groups, as is pointed out in Remark 1.2 of [FrPu 2007]. For a version of the result of Atiyah and Bredon for other coefficients, see [FrPu 2003].

The following proposition shows that exactness of the Atiyah-Bredon sequence at and is implied by exactness of the rest of the sequence.

Proposition 4.5.

Let denote either equivariant or basic cohomology. If for some , the truncated Atiyah-Bredon sequence

is exact, then also

One way to see this is to regard the maps in the sequence as differentials in the spectral sequence associated to the filtration . The assumption implies that this spectral sequence collapses, and because it converges to , the statement follows. This argument was used in [Bre 1974, p. 846]. It can also be proven by hand: for the injectivity of , a straightforward diagram chase shows that that for every , we have . For exactness at , another diagram chase proves that for every , the image of equals the image of .

5. Cohen-Macaulay modules over graded rings

In the literature, the Cohen-Macaulay property usually is considered for modules over Noetherian (local) rings. In our situation, it is natural to consider the graded version of this concept.

Using the language of e.g. [BrHe 1993, Section 1.5], a graded ring (graded over the integers) is *local if it has a unique *maximal ideal, where a *maximal ideal is a graded ideal which is maximal among the graded ideals. Thus, is a Noetherian graded *local ring. Note that in general a *maximal ideal is not necessarily maximal.

Let be a Noetherian graded *local ring, with *maximal ideal . Then the depth of a finitely generated graded module over is defined as the length of a maximal -regular sequence in :

The Krull dimension of , denoted , is defined as the Krull dimension of the ring , where , i.e., the supremum of the lengths of chains of prime ideals in containing .

Definition 5.1.

A finitely generated graded module over a Noetherian graded *local ring is Cohen-Macaulay if .

Instead of working with the graded notions, we could equally well localize everything at the *maximal ideal (as e.g. Franz and Puppe [FrPu 2003] do it in their proof of the exactness of the Atiyah-Bredon sequence for other coefficients), because of the following proposition:

Proposition 5.2.

Let be a finitely generated graded module over a Noetherian graded *local ring with *maximal ideal such that is a field (e.g. ). Then the following conditions are equivalent:

-

(1)

is Cohen-Macaulay over

-

(2)

is Cohen-Macaulay over the local ring

-

(3)

is Cohen-Macaulay over the local ring for all (not necessarily graded) maximal ideals .

If these conditions are satisfied, then the Krull dimensions of the -module and the -module coincide.

Proof.

The equivalence of and is [BrHe 1993, Exercise 2.1.27.(c)] and valid without the additional assumption that is a field; note that there, Cohen-Macaulay modules (over arbitrary Noetherian rings) are defined via condition of this proposition.

We only explain the equivalence of and . In fact, we show that the depths of and and the Krull dimensions of and coincide without using the Cohen-Macaulay property. We have by [BrHe 1993, Prop. 1.5.15.(e)]. For the equality of the dimensions, note that , where varies over all maximal ideals in , so obviously . For the other inequality we use that if is another maximal ideal, then by [BrHe 1993, Theorem 1.5.8.(b)] the largest graded prime ideal satisfies . Because of the assumption that is a field, is properly contained in the *maximal ideal , so , and hence . ∎

The proof implies that for a finitely generated module over an arbitrary Noetherian graded *local ring , the inequality for the localized module over translates to the corresponding one for : if , then

For later use, we collect some well-known lemmata on Cohen-Macaulay modules. The first two, which describe how depth and the Cohen-Macaulay property behave with respect to short exact sequences, will be crucial for all our proofs that the equivariant cohomology of actions with certain properties is Cohen-Macaulay.

Lemma 5.3 ([BrHe 1993, Proposition 1.2.9]).

Let be an exact sequence of finitely generated graded modules over a Noetherian graded *local ring . Then

-

(1)

-

(2)

-

(3)

Lemma 5.4.

Let be an exact sequence of finitely generated graded modules over a Noetherian graded *local ring . Then the following statements are true:

-

(1)

If and are Cohen-Macaulay of the same Krull dimension , then is also Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension .

-

(2)

If and are Cohen-Macaulay of the same Krull dimension , then either or is also Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension .

Proof.

We have , where the supremum is taken over those prime ideals with , see [Ser 2000, Ch. III, B.1]. Thus, Proposition I.4 of [Ser 2000] implies that for any short exact sequence of finitely generated -modules. To see how the depths of the modules relate, use Lemma 5.3: in case , it implies that , since in any case. In case and , the lemma implies that . ∎

Remark 5.5.

If and are Cohen-Macaulay of the same Krull dimension and , then is not necessarily Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension . For example, consider the short exact sequence .

Example 5.6.

If a -action on a compact manifold and is such that , then is a Cohen-Macaulay module of Krull dimension . In fact, if we choose points such that is the disjoint union of the , then

where is the unique isotropy algebra of . Thus, is the sum of Cohen-Macaulay modules of Krull dimension , and Lemma 5.4 implies that it is Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension itself.

Lemma 5.7 ([FrPu 2003, Lemma 4.3]).

Let be a finitely generated module over a Noetherian graded *local ring . If is Cohen-Macaulay and a non-zero submodule, then .

Proof.

We only need to show . Let be an associated prime ideal of , i.e., is the annihilator of some element in . Because , we have . Furthermore, Proposition 1.2.13. of [BrHe 1993] is true in the graded setting, and hence . ∎

6. Cohen-Macaulay actions

In this section, we introduce our main object of study. Examining the proof that equivariant formality implies the exactness of the Atiyah-Bredon sequence [Bre 1974] (see also [FrPu 2003]), one sees that the relevant property of is not that it is a free -module, but that it is a Cohen-Macaulay module of Krull dimension .

It is proven in [FrPu 2003, Proposition 5.1] that for any -action on the Krull dimension of the -module equals the dimension of a maximal isotropy algebra (i.e., the Lie algebra of an isotropy group).

Definition 6.1.

Let act on a compact manifold . We say that the action is Cohen-Macaulay if is a Cohen-Macaulay module over .

If denotes the lowest occuring dimension of a -orbit, i.e., but , then the dimension of a maximal isotropy algebra is . With this definition, Theorem 4.4 is still valid in the sense of the following Theorem.

Theorem 6.2.

Let act on a compact manifold , and denote by the lowest occuring dimension of a -orbit. Then the following conditions are equivalent:

-

(1)

The action is Cohen-Macaulay

-

(2)

The sequence

(which we will refer to as the Atiyah-Bredon sequence) is exact.

Proof.

For the proof of , we follow [FrPu 2003] closely. The proof of naturally reverses the arguments of .

Without loss of generality, we can assume that the action is effective, i.e., and . For both directions we will use the following consequence of the localization theorem, see [FrPu 2003, Lemma 4.4],

| (6.1) |

and the fact that exactness of the Atiyah-Bredon sequence is equivalent to the exactness of the sequences

| (6.2) |

for , see [FrPu 2007, Lemma 4.1].

Assuming the action is Cohen-Macaulay, we prove by induction that (6.2) is exact and that is Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension . Assume we have shown that is Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension . For the exactness of (6.2), we show that is the zero map. Since is Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension , the image of under the map in question is, by Lemma 5.7, either zero or has Krull dimension as well. But on the other hand, (6.1) implies that its Krull dimension is at most , hence the image vanishes and (6.2) is exact. Because by Example 5.6, Lemma 5.3 implies that . Noting that , this shows together with (6.1) that is Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension .

For the other direction, assume that the sequences (6.2) are exact. By Example 5.6, is a Cohen-Macaulay module of Krull dimension . Using , Lemma 5.3 implies that if is a Cohen-Macaulay module of Krull dimension , then and hence (6.1) implies that is Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension . By induction it follows that is Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension . ∎

Remark 6.3.

If the lowest occuring dimension of a -orbit is , then a generic -dimensional subtorus acts locally freely. Choosing another subtorus such that , we have that acts on with fixed points, and as graded rings by the commuting action principle [GuSt 1999, Section 4.6]. Note that is not necessarily a manifold. The -action on is Cohen-Macaulay if and only if the -action on is equivariantly formal. Note also that the -action on and the -action on have the same orbit space. With this reduction one can alternatively deduce the theorem above from Theorem 4.4 (respectively a version for more general spaces than differentiable manifolds). Modulo the fact that is not a manifold, also the results in Section 7 and 8 (but not 9 and 10) could be derived similarly. We believe however that is is illuminating to see that the existing proofs can easily be modified from the equivariantly formal to the Cohen-Macaulay setting.

In the case , i.e., , the theorem reduces to Theorem 4.4 by Atiyah, Bredon, Franz and Puppe because of

Proposition 6.4.

If the -action has fixed points, then it is Cohen-Macaulay if and only if it is equivariantly formal.

Proof.

Note that in the proof of in Theorem 4.4 by Franz and Puppe [FrPu 2007] this argument is not needed, as they directly show freeness of .

Examples 6.5.

-

(1)

Let act on , and denote by the connected component of the kernel of the action, i.e., of the subgroup of consisting of the elements that act trivially. Then the -action on is Cohen-Macaulay if and only if the -action on is Cohen-Macaulay.

-

(2)

-actions with only one local isotropy type are Cohen-Macaulay. The Atiyah-Bredon sequence in this case is .

-

(3)

Let act on effectively and with cohomogeneity one, i.e., the regular orbits have codimension one. There are at most two singular orbits, all of which have codimension two (recall that for us only the local isotropy type is relevant). If the action is locally free, then the action is Cohen-Macaulay by the previous example, so we can assume there exists at least one singular orbit. In this case, the singular orbits have dimension because the regular orbits are -fibre bundles over the singular orbits, i.e., . To see that the Atiyah-Bredon sequence in this case is exact, we need to show that is the zero map. It is known that the orbit space is homeomorphic to the closed interval , and the orbit space of the regular stratum is either the open interval or a half-open interval , where the latter case can only occur in the non-orientable case. In any case, for . But by [GGK 2002, Example C.8], which shows that the map in question is the zero map. Thus, cohomogeneity-one actions are Cohen-Macaulay.

The following proposition is a generalization of Corollary 4.3.

Proposition 6.6.

If the action is Cohen-Macaulay, then the bottom stratum of the action equals . More generally, this is true if is injective.

Proof.

Obviously is contained in the bottom stratum. If there is a component of the bottom stratum not contained in , then . Then, the Thom class of (with respect to any chosen orientation on the normal bundle) is a nonzero class in (because it restricts to the Euler class of which is nonzero by [Duf 1983, Proposition 3]) that restricts to zero on . ∎

Proposition 6.7.

If the action is Cohen-Macaulay, then for every -invariant closed subspace containing , we have .

Proof.

Because is injective, is injective as well, and its image does not intersect . Exactness of the Atiyah-Bredon sequence at implies that the image equals the image of . Because is supposed to contain , this subspace of is also the same as the image of , whence the induced map is an isomorphism. ∎

The following lemma is obvious.

Lemma 6.8.

Assume the lowest occurring dimension of a -orbit is the same for every connected component of . Then the action is Cohen-Macaulay if and only if the action on each connected component is Cohen-Macaulay.

7. Morse-Bott functions

It is well-known that a -action admitting a Morse-Bott function whose critical set is the fixed point set of the action is equivariantly formal. Replacing the fixed point set by the set of lowest dimensional orbits, we obtain the following generalization of this criterion:

Theorem 7.1.

Assume acts on a compact manifold , and let be the dimension of the smallest occuring orbit. If there exists an invariant Morse-Bott function whose critical set is equal to a union of connected components of , then the action is Cohen-Macaulay. Moreover, if is the absolute minimum of , then is surjective.

Proof.

For a real number , let

Let be a critical value of , and be the connected components of the critical set at level . Denote by and the disk respectively sphere bundle in the negative normal bundle (see e.g. [AtBo 1982, Section 1]) of . We write for the rank of . Let be the equivariant Euler class of . Consider the following diagram, in which the top row is the long exact sequence of the pair .

The two vertical arrows on the left are isomorphisms (one because of excision, and the other is the inverse of the Thom isomorphism), and because has no -fixed vectors, where is the isotropy group of , multiplication with the Euler classes is injective by [Duf 1983, Proposition 4]. Thus, is injective and we obtain short exact sequences

For the absolute minimum of , is the sum of Cohen-Macaulay modules of Krull dimension , and hence Cohen-Macaulay by Lemma 5.4. If for some critical value we already know that is Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension , the short sequence above, combined with Lemma 5.4 and the fact that is Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension as well, implies that is Cohen-Macaulay of the same Krull dimension. ∎

Remark 7.2.

Note that is automatically an equivariantly perfect Morse-Bott function as all components of are equivariantly self-completing, cf. [AtBo 1984, Prop. 1.9.]

8. Equivariant disk bundle decompositions

In this section, we will prove a generalization of a theorem of Harada, Henriques and Holm, see [HHH 2005], in particular Theorem 2.2 of the unpublished version. For us, a cell bundle is a -equivariant oriented disk bundle over a compact -manifold . The dimension of a cell bundle is the fiber dimension.

We say that a compact manifold has a -invariant disk bundle decomposition if it can be built from a union of zero-dimensional cell bundles, and successively attaching cell bundles. The attaching maps are not required to map the boundary into smaller dimensional cell bundles.

Theorem 8.1.

Let be a fixed integer. Let be a compact -manifold that admits a finite -invariant disk bundle decomposition into finitely many even-dimensional cell bundles that satisfy the following conditions:

-

(1)

acts on with only one local isotropy type of dimension

-

(2)

.

Then the action is Cohen-Macaulay.

Proof.

As the maximal dimension of an isotropy algebra is , we know [FrPu 2003, Proposition 5.1] that the Krull dimension of is .

As in the definition of a disk bundle decomposition, let be the union of zero-dimensional cell bundles, and be the space obtained by attaching the first cell bundles. We prove by induction that is Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension , and . First, is the sum of Cohen-Macaulay modules of the form , where is the unique -dimensional isotropy algebra of . So is Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension by Lemma 5.4, and .

We claim that in the long exact sequence of the pair , the boundary operator vanishes. For this, it is sufficient to show that . Let be the cell bundle that gets attached to . Denote its dimension by and the unique isotropy algebra of by . Then

| (8.1) |

so by assumption , vanishes. Thus, the boundary operator in the long exact sequence of the pair vanishes and we obtain a short exact sequence

It follows that . Because (8.1) implies that is Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension , is also Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension by Lemma 5.4. ∎

9. Equivariant cohomology and the bottom stratum

Although it is not an equivalent characterization of equivariant formality, the injectivity of the restriction map due to the torsion-freeness of is an important property of equivariantly formal actions. In this section, we replace by the bottom stratum of the action, and find an algebraic characterization of injectivity of which has an interesting geometric consequence, see Theorem 9.6. This will be applied in Section 10.

If acts on a manifold , then we say that is invisible if no complexified nonregular isotropy algebra of the -action on is contained in . If is compact, this is by Lemma 3.2 equivalent to saying that for every nonregular isotropy algebra of the action, is in the kernel of . This motivates the terminology.

Proposition 9.1.

Let act on a compact manifold , and let denote the bottom stratum of the action. Then the natural map

is injective if and only if for every , does not contain any invisible element.

Proof.

Assume first that is invisible for , i.e., the only complexified isotropy algebra contained in is . Because the equivariant push-forward map is injective [Duf 1983, Proposition 4], the image of has the same support as and thus maps to zero in by Lemma 3.2.

Assume now that for , contains no invisible elements. We prove that is injective by induction over the length of the longest chain of isotropy algebras.

If this length is , i.e., the action has only one local isotropy type, we have and the claim is trivial. Assume the proposition is proven for all actions with , and let act on with .

Let denote the minimal nonregular isotropy algebras of the action, i.e., if is any isotropy group, then either is the regular isotropy group (i.e., if the action is effective) or . Consider the map

By Lemma 3.2, the kernel of consists of those whose support does not contain any . But the are exactly the minimal isotropy algebras, so we get

By assumption (choose a regular ), such invisible elements do not exist, so is injective. The longest chains of isotropy algebras for the -actions on are shorter than the one of the action on , so by induction we know that the maps , induced by the inclusions, are injective. It follows that

is injective. But this map consists only of copies of the natural maps induced by the inclusions of components of the bottom stratum, and thus, has to be injective itself. ∎

Next, we find a geometric consequence of the existence of an invisible element . Duflot [Duf 1983, proof of Theorem 1] proves that for every , the push-forward of the inclusion is injective, i.e., the corresponding Gysin sequence is in fact a short exact sequence

| (9.1) |

Note that this is a sequence of -modules, see e.g. the discussion on the equivariant push-forward map in [AtBo 1984, §2], or [GGK 2002, p. 221]. These considerations imply the following lemma:

Lemma 9.2.

Let act on a compact manifold . If is invisible, then is not in the kernel of the map .

Proof.

If we can show that an invisible element can never be in the kernel of for , then the claim follows. This kernel is by (9.1) the same as the image of . For any , we have because of the injectivity of . But on the other hand, if we choose a point in each connected component of , then by Lemma 3.1, and the are nonregular isotropy algebras on . ∎

Corollary 9.3.

Let act nontransitively on a connected compact manifold . If is acyclic, i.e., , then there are no invisible elements in .

Proof.

Assume without loss of generality that the -action is effective. Let be invisible. By Lemma 9.2, defines a nonzero cohomology class in , which implies that is a -form. In other words, is invisible. But the support of contains the complexification of every isotropy algebra, cf. Proposition 3.3. This means that the action is locally free, i.e., . As satisfies Poincaré duality, this is only possible if is a point, i.e., the action is transitive. ∎

Definition 9.4.

We call a face of the orbit space. We say that is closed-face-acyclic if its closed faces are acyclic; that means that for any point , we have . If the open faces of are acyclic, i.e., if for all we have , we call open-face-acyclic. We say that the orbit space is almost open-face-acyclic if we have for all not contained in the bottom stratum of the action.

Remark 9.5.

For torus manifolds, the notion of face-acyclicity as introduced by [MaPa 2006] is the same as our condition of having closed-face-acyclic orbit space, but note that they use integer coefficients instead of the reals.

With this notation, we obtain

Theorem 9.6.

If is almost open-face-acyclic, then the natural map is injective.

10. Actions with face-acyclic orbit space

The goal of this section is to prove that actions with open-face-acyclic orbit space (see Definition 9.4) on orientable compact manifolds are Cohen-Macaulay, see Theorem 10.24. In Subsection 10.1 we investigate the general topological structure of actions with (almost) open-face-acyclic orbit space, such as the dimensions of the strata or the structure of the bottom stratum. In particular, if is the dimension of the smallest occuring orbit, will be seen to be a connected graph, just as the -skeleton of an equivariantly formal action satisfying the GKM conditions, see Subsection 10.2. In Subsections 10.3 and 10.4 we finish the proof that actions with open-face-acyclic orbit space are Cohen-Macaulay, following ideas by Masuda and Panov [MaPa 2006], but with certain differences as mentioned in the introduction. Combined with a statement of Bredon [Bre 1974], our result characterizes equivariantly formal actions on orientable compact manifolds with via the orbit space, see Subsection 10.5.

10.1. Open- and closed-face-acyclicity

For the following proposition, cf. also the remark after Proposition 9.3 of [MaPa 2006].

Proposition 10.1.

If the orbit space of an effective -action on an oriented compact manifold is almost open-face-acyclic, then one of the following statements holds:

-

(1)

is connected.

-

(2)

The orbit space is open-face-acyclic, i.e., consists of finitely many isolated orbits. Moreover, they are all of the same dimension, i.e., there exists such that . In addition, is connected.

Proof.

Assume that is not connected. In particular, the action is not locally free and hence has at least two local isotropy types.

Let be a component of . We have to show that is an orbit. The components of isotropy manifolds are partially ordered by inclusion, the unique maximal element being itself. Since the bottom stratum of is disconnected by assumption, we may choose a minimal such component with the property that the bottom stratum of the -action on is disconnected, but contains . Let the other components of the bottom stratum of be denoted by .

We claim that is disconnected. Assume this is not the case, and recall

For every with , the bottom stratum of the -action on is connected, and hence one of the , . Further, for two such singular points such that , their respective bottom strata are, because of connectedness, contained in and coincide. Therefore, if we let

then is a disjoint union into nonempty subsets, and hence is disconnected.

Consider now the first terms of the long exact sequence in basic cohomology of the pair :

It follows that . But since , and satisfies Poincaré duality, the almost open-face-acyclic condition implies that the -action on has cohomogeneity one. In particular, it has exactly two singular orbits, one of which is . Because is a torus, the regular orbits are -fibre bundles over the singular orbits, and hence the two singular orbits have equal dimension.

It follows that consists of isolated orbits, and whenever two of those orbits can be joined by a sequence of ’s such that the -action on has cohomogeneity one (we say: they are linked), they are of the same dimension. We still need to show that any two of those orbits are linked. If this was not the case, choose an arbitrary component , and let be minimal with the property that the bottom stratum of has a component linked with and a component not linked with . In other words, for all singular , the components of the bottom stratum of are either all linked with or all not linked with . By an analogous argument as above, is disconnected. But this implies that the -action on has cohomogeneity one, which is a contradiction. ∎

Example 10.2.

An easy example for an action whose orbit space is almost open-face-acyclic but not open-face-acyclic, is the -action on is given by . The orbit space is the disk , and .

For the rest of the section, will denote the dimension of the smallest occuring orbit.

Lemma 10.3.

Let act locally freely on a manifold (e.g. the regular stratum of another -action) such that . Then for every , the map in cohomology induced by the orbit map , is surjective.

Proof.

It suffices to prove that is surjective, as is generated by . Fix a basis of , with dual basis . Let be a connection form, i.e., a -invariant map such that for every , we have . Note that a choice of connection form is equivalent to the choice of a -invariant horizontal distribution, e.g., the orthogonal complement of the orbit with respect to some -invariant Riemannian metric on .

We obtain one-forms on (these are sometimes called connection forms, see e.g. [GuSt 1999, p. 23]). We claim that is a closed basic two-form. The are clearly -invariant, as is -invariant. Thus,

and hence is a closed basic two-form. By our assumption it follows that the are basic exact, i.e., there exist basic one-forms such that the are closed and thus define cohomology classes on . The pull-back of via an orbit map of a point is the left-invariant one-form given by since

Since those left-invariant one-forms span , the claim follows. ∎

For , let . Observe that for , we have , and if , even .

Proposition 10.4.

If the orbit space of a -action on an orientable manifold is open-face-acyclic, then for all we have .

Proof.

The subsequent lemma implies that for every and such that and such that there is no with , we have (apply the lemma to the -action on ). The claim follows by induction, since for it is clear by Proposition 10.1. ∎

Lemma 10.5.

If the -action is effective and , then for every such that there is no with , we have .

Proof.

By Lemma 10.3, the condition on the basic cohomology implies that for any regular point , the orbit map of induces a surjective map . If is such as in the statement of the lemma, then we can choose so small that , where is the sphere bundle of radius in the normal bundle of , is contained in the regular stratum. We furthermore may assume that , restricted to , is a diffeomorphism onto its image. Then, the map , induced by the orbit map of some point in , factors through , and we obtain a surjective map . On the other hand,

As is a finite group and we are dealing with -coefficients, we have , see e.g. Borel et al. [BBFMP 1960, Cor. III.2.3]. If is some complement of the identity component in , i.e., , we have . Since is strictly lower dimensional than , it follows that can only map surjectively onto the -dimensional space if the sphere and are one-dimensional. But this implies that has codimension two in , and thus , which finishes the proof. ∎

Corollary 10.6.

If the orbit space of a -action on a compact orientable manifold is open-face-acyclic, then

-

(1)

for . The dimension of is equal to the number of components of .

-

(2)

For , the natural map is an isomorphism.

-

(3)

For , .

Proof.

The first part follows from Proposition 10.4 because every satisfies Poincaré duality. For the second part, write as the composition

Using the exact cohomology sequences of the respective pairs, the first part of the corollary implies that each of those maps is an isomorphism if .

The same argument gives that each map in the composition

is an isomorphism if , hence the third part follows. ∎

Corollary 10.7.

If the orbit space of an effective -action on a compact orientable manifold is open-face-acyclic, then .

Proof.

Proposition 10.4 implies for regular . Thus, . ∎

Corollary 10.8.

If the orbit space of an effective -action on an orientable compact manifold is open-face-acyclic, then for all , we have . Consequently, the natural -representation on the normal space has exactly weights.

Proof.

For , we have and thus It follows that the -representation has at most many weights. Because of effectiveness, the second claim follows. ∎

For any , the isotropy representation at induces -representations on the tangent and normal spaces and . We have as -modules. Corollary 10.8 implies that and , where the and are the weight spaces of the respective weights . Because acts trivially on , we have . The restriction map is a one-to-one-correspondence between the weights of the - and the -representations on . The weights are constant along in the following sense:

Lemma 10.9.

The weights of the -representation on , coincide with the weights of the -representation on . Moreover, the normal bundle splits equivariantly as .

Proof.

Proposition 10.10.

If the orbit space of a -action on an orientable compact manifold is open-face-acyclic, then it is also closed-face-acyclic, i.e., for all . In particular, .

Proof.

We show that the map induces an isomorphism on basic cohomology by regarding it as the composition . To do this, we have to show that for all , the map is an isomorphism. Choose a point in each connected component of , together with disjoint neighborhoods of that have as strong equivariant deformation retracts, and are diffeomorphic to the normal bundles .

In the diagram, the vertical maps on the sides are isomorphisms by excision. Thus, we need to show that the maps are isomorphisms, which by our choice of amounts to show that for every , the spaces and are homotopy equivalent.

Let , be the weights of the normal bundle as in Lemma 10.9. Any vector can be uniquely written as , where . Because the are -invariant, this defines a -invariant map

It follows that the map

is well-defined. It is clearly surjective, and injectivity follows because the -orbits in are products of -orbits in by Corollary 10.8. Noting that under this map, corresponds to , the desired homotopy equivalence follows. ∎

Proposition 10.11.

If the orbit space of a -action on an orientable compact manifold is open-face-acyclic, then the sequence

where the first map is induced by the inclusion, is exact.

Proof.

The proof is the same as the standard proof that the cellular cohomology of a CW complex computes the standard cohomology. Let cause nonexactness of the sequence

at for some , i.e., but . Because , the exact sequence of the triple in basic cohomology implies that there is an element that is mapped to under the natural restriction map. We claim that defines a nontrivial element in . If that was not the case, would be in the image of the boundary map . But since by the third part of Corollary 10.6, this would produce a contradiction to the assumption that . Thus, is nontrivial. By the second part of Corollary 10.6, this implies that , which is in contradiction to Proposition 10.10.

To finish the proof, either use Proposition 4.5 for basic cohomology, or redo the same argument as above to show that is one-dimensional. ∎

Remark 10.12.

This is a version of the Atiyah-Bredon sequence for basic cohomology. Unfortunately, we do not have a proof of the Cohen-Macaulayness of torus actions whose orbit space is open-face-acyclic that makes use of this sequence.

Note that for a general Cohen-Macaulay action, the basic version of the Atiyah-Bredon sequence is not necessarily exact. For example, consider the -action on the -sphere given by

It has exactly two fixed points and is thus equivariantly formal by criterion listed in Section 4. But the boundary operator is not surjective, as .

10.2. The -skeleton

By the results of Section 10.1 (in particular Propositions 10.1, 10.4, and Corollary 10.8), the -skeleton of an action on an orientable compact manifold with open-face-acyclic orbit space behaves similarly to the one-skeleton of an equivariantly formal action satisfying the so-called GKM conditions (see e.g. [GuSt 1999, Section 11.8]). The only difference is that instead of being composed of two-spheres, is a union of submanifolds on which acts with cohomogeneity one. If two such cohomogeneity one submanifolds meet, their intersection consists of either one or two -dimensional orbits. can be thought of as a graph, with the elements of as vertices. The vertices will be identified with the corresponding -dimensional orbits, and also with points on that orbit. For we write for , when understood as a vertex. There is one edge for every submanifold with connecting its two -dimensional orbits. Multiple edges between two vertices can occur. This graph is -valent, with . Although the orbit space is not necessarily a convex polytope, we will refer to the as faces.

Remark 10.13.

In view of Remark 6.3, if we choose a -dimensional subtorus acting locally freely, then the -action on satisfies the usual GKM conditions.

Example 10.14.

Consider the -action on given by . The bottom stratum consists of the three one-dimensional orbits, which are circles, and is a triangle. The diagonal acts freely on , with . The induced -action on has the same orbit space as the -action on .

For every oriented edge , let denote the initial vertex, the terminal vertex, and we write . There is a unique weight of the -representation on with kernel .

Lemma 10.15.

For every two edges and with , there is a unique edge with such that .

Proof.

This is a consequence of Lemma 10.9 and the discussion preceding it. ∎

10.3. A Chang-Skjelbred Lemma

Although the statements here are more general, most of the arguments in this section are taken from Sections 6 and 7 of [MaPa 2006]. As before, we consider a -action on an orientable compact manifold with open-face-acyclic orbit space, and the bottom stratum being the union of the -dimensional orbits.

For a face , let be the equivariant Thom class of in with respect to any orientation of the normal bundle, and the equivariant Euler class of the normal bundle of . The restriction of to is , see e.g. [GGK 2002, p. 221].

Lemma 10.16.

Let be a face, and the codimension of the closed -invariant submanifold in . Then for all ,

For , we have .

Proof.

For , the statement is obvious, so let . By Lemma 10.9, the normal bundle splits as the sum of -equivariant two-plane bundles . Thus, . The bundle , restricted to , is

where is a complement of the identity component in , i.e., .

We calculate the Euler class of the -equivariant bundle in a way similar to [GGK 2002, Lemma I.3]. See also [BoTu 2001] for the description of the equivariant Euler class in the Cartan model. Note that this bundle is trivial as a -equivariant bundle. For this, we choose a -invariant connection form such that the -orbits are horizontal. Denoting the natural projection by , one shows as in Lemma I.3 of the reference above that

for all , where is the projection along the decomposition . The form part vanishes because the curvature of is zero by choice of . Using the isomorphism , the claim follows. ∎

Note that because of the lemma, the restricted Euler class is independent of the chosen orientation of the normal bundle.

The next lemmas are analogous to Lemma 6.2 and 7.3 of [MaPa 2006]; the only difference is that we are not allowed to subtract the restrictions of equivariant differential forms to different components of the bottom stratum.

Lemma 10.17.

Let be a closed invariant subspace of containing , and . Choose an edge and write and . Then the polynomials and coincide on the intersection , where is the isotropy algebra of .

Proof.

Using Lemma 3.1, we obtain the following diagram, in which the upper right space is nothing but .

Since the diagram commutes and , we see that the image of in the bottom right space is of the form for some and . As the restrictions of and to are given by those summands for which is a -form, the lemma follows. ∎

Let be a face of , and a vertex of . We denote by the ideal generated by all with .

Lemma 10.18.

Let be a closed invariant subspace of containing , and let be a face of . For every , if for some vertex , then for every vertex .

Proof.

Suppose for some vertex , i.e.

for some . Now choose another vertex that is joined to by an edge . By Lemma 10.15, for every in the sum above there is a unique edge with such that . If we define

where is any polynomial with , then Lemma 10.17 implies that vanishes on . In particular it is divisible by the weight that vanishes on , and hence .

This completes the proof because the -skeleton of is connected by Proposition 10.1. ∎

For every closed invariant subspace containing , define

For , i.e., the bottom stratum being the fixed point set, is the torsion submodule of .

Proposition 10.19.

For every closed invariant subspace containing , the quotient is generated by the restrictions of the elements to .

Proof.

Now that we have transferred the necessary Lemmata 10.16 and 10.18 to our situation, the proof is exactly the same as the proof of Proposition 7.4 in [MaPa 2006], and we therefore omit it. It does not complicate things to consider instead of the whole manifold , but note that it is important that contains the whole -skeleton. ∎

As a corollary we obtain a version of the Chang-Skjelbred Lemma for actions with open-face-acyclic orbit space, compare [ChSk 1974, Lemma 2.3].

Corollary 10.20.

-

(1)

For every closed invariant subspace containing , we have as -modules.

-

(2)

The sequence

is exact.

10.4. Actions with open-face-acyclic orbit space are Cohen-Macaulay

Masuda and Panov [MaPa 2006, Definition 5.3] define the face ring of as the graded ring

where is the ideal generated by elements of the form

Here, in case and have nonempty intersection, is the unique smallest face containing and , and zero otherwise. The notation means that is a connected component of . One proves just as in [MaPa 2006, Section 6] that the canonical (after fixing compatible orientations on all normal bundles) homomorphism is well-defined and injective, and by Proposition 10.19 and Theorem 9.6 it is surjective as well. Note that because we have already proven injectivity of , we can work with itself instead of .

Example 10.21.

Consider the -action on defined by and the -action on defined by . These actions are Cohen-Macaulay (the latter even equivariantly formal) and their orbit spaces coincide and are open-face-acyclic. Hence the equivariant cohomologies and are isomorphic as rings. Alternatively, this follows from Remark 6.3 as the diagonal circle in acts freely on such that the induced -action on coincides with the action described above.

Lemma 10.22.

If is a face such that for every subface , any intersection of a face with is connected, then is surjective.

Proof.

By Proposition 10.19 and Theorem 9.6, is generated by the Thom classes of faces in . Let be such a Thom class, with . There is a unique maximal face in whose intersection with is . For a -invariant metric on , we have that the normal bundle of in , restricted to , coincides with the normal bundle of in . Thus, is mapped onto . ∎

Remark 10.23.

The condition on is necessary. For example, consider the action of a two-dimensional maximal torus on . If is a one-dimensional stabilizer, then is not surjective. In fact, , but .

Theorem 10.24.

Every torus action on a compact orientable manifold with open-face-acyclic orbit space is Cohen-Macaulay.

Proof.

We prove the theorem by induction on the dimension of the orbit space. As in [MaPa 2006, Theorem 9.3] we blow up faces of (i.e., we replace submanifolds by the complex projectivizations of the respective normal bundles , see [MaPa 2006, Section 9] or [MMP 2007, Section 8]) successively until we arrive at a -manifold whose orbit space satisfies that the intersection of any two faces of is connected (i.e., empty or a face). In order to be able to apply Lemma 10.22, we need to choose the faces to be blown up such that the assumptions for the lemma are satisfied. More precisely, let

It is clear that contains all vertices. If there are edges not contained in , we can at first blow up along vertices until we obtain such that all edges of are in . Continuing this process with the higher-dimensional faces, we obtain a sequence of -manifolds with collapse maps

such that is obtained from by blowing up a face . Note that because , every subface of the new facet is in .

is a *local positively graded ring, with *maximal ideal generated by the homogeneous elements of positive degree. Lemma 8.2. of [MaPa 2006] implies that is Cohen-Macaulay as *local graded ring. Considering as a module over itself, a graded version of [Ser 2000, Prop. IV.12] implies that it is also Cohen-Macaulay as an -module. Its Krull dimension is , as the maximal dimension of an isotropy algebra of is . It remains to show that if the action on the blown-up manifold is Cohen-Macaulay, then so is the original one.

Assume we have already shown that is Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension ; we show it for .

By Lemma 10.22 and the observations above, the lower horizontal sequence is exact. The left vertical map is an isomorphism, and hence the upper horizontal sequence is exact as well. We know that is Cohen-Macaulay, and and are Cohen-Macaulay by induction. Since all Krull dimensions are equal, it follows that is either the zero module or Cohen-Macaulay of Krull dimension by the second statement of Lemma 5.4, and then the first statement of Lemma 5.4 implies that is Cohen-Macaulay of the same Krull dimension. ∎

10.5. The equivariantly formal case

For , i.e., , the converse of Theorem 10.24 was proven by Bredon, see [Bre 1974, Corollary 3]. We thus have

Theorem 10.25.

An effective -action on an orientable compact manifold with is equivariantly formal if and only if its orbit space is open-face-acyclic.

Still in the case , there is a relation between the number of connected components of and the Betti numbers of . For an arbitrary -action on a compact manifold , Duflot calculated the Poincaré series of in terms of the components of . Letting denote the number of connected components of , her result simplifies in the case of an action with open-face-acyclic orbit space to the following

Proposition 10.26 ([Duf 1983, Theorem 2]).

For a -action with open-face-acyclic orbit space, the Poincaré series of is given by

Note that her notation is slightly different from ours: she indexes the by the dimensions of the isotropy groups, not the dimensions of the orbits. Using the isomorphism between and the face ring of , Masuda and Panov [MaPa 2006, Theorem 5.12, Theorem 7.7] obtain the same equation for torus manifolds with using the fact that the Poincaré series of the face ring was determined in [Sta 1991, Proposition 3.8]. However, Proposition 10.26 follows independently from this isomorphism, as we only combine our calculation of the codimensions of the in Corollary 10.8 with Theorem 2 of [Duf 1983].

On the other hand, if acts on an orientable compact manifold with open-face-acyclic orbit space and , the action is equivariantly formal by Theorem 10.25. Thus, we know that in this case as a graded -module, and hence the Poincaré series of is given by , where (note that the odd Betti numbers vanish since maps injectively into , and the fixed point set consists of isolated points). Equating these two expressions for the Poincaré series, we obtain that the determine the and vice versa:

Proposition 10.27.

For a -action on an orientable compact manifold with open-face-acyclic orbit space and , we have

For an arbitrary equivariantly formal action, Bredon related the Poincaré series of with the Poincaré series of the (compact cohomology of the) components of using the Atiyah-Bredon sequence, see the equation on the bottom of p. 846 in [Bre 1974]. For a -action with open-face-acyclic orbit space, his equation simplifies to Proposition 10.27. Note that, using Poincaré duality for and the components of , one can see that in the case of an equivariantly formal action on an orientable compact manifold, Theorem 2 of [Duf 1983] is the same as the equation by Bredon.

Example 10.28.

Consider the following -actions on the -dimensional manifolds and : on , we regard the action given by the product of the -action on defined by

and the standard -action on . On we have the -action given by

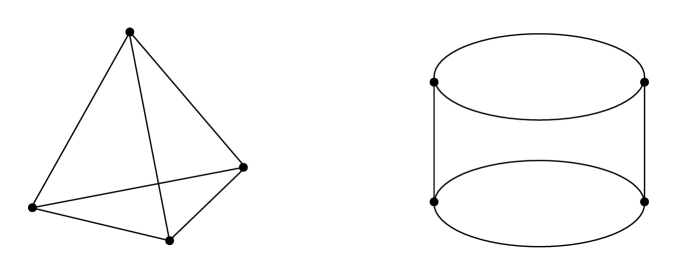

Both these actions are equivariantly formal (e.g. because they have exactly fixed points, or because in both cases) and have open-face-acyclic orbit space. As the cohomologies of and are isomorphic as graded vector spaces, the numbers of connected components of have to coincide for these actions. In fact, they are , , and . For , the orbit space is a tetrahedron, whereas for it is a cylinder, see Figure 1.

In the pictures, the dots represent the fixed points. Note that whereas the equivariant cohomologies and are isomorphic as graded -modules, their multiplicative structures do not coincide. In fact, the face rings of the tetrahedron and the cylinder are not isomorphic (e.g. in the face ring of the cylinder the product of the Thom classes of the top and the bottom face is zero, whereas in the face ring of the tetrahedron two elements of degree two whose product is zero are linearly dependent).

Note that the tetrahedron also appears as the orbit space of e.g. the -action on given by

with the vertices corresponding to the one-dimensional orbits. By Theorem 10.24, this action is Cohen-Macaulay, with of Krull dimension . In fact, is isomorphic to as a ring. In view of Remark 6.3, this is clear as the diagonal circle in acts freely on such that the induced -action on is the action described above.

References

- [AlPu 1993] C. Allday and V. Puppe, Cohomological methods in transformation groups, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics 32, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1993.

- [Ati 1967] M. F. Atiyah, -theory, Lecture notes by D. W. Anderson. W. A. Benjamin, Inc., New York-Amsterdam 1967.

- [Ati 1974] M. F. Atiyah, Elliptic operators and compact groups, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, vol. 401, Springer-Verlag, Berlin 1974.

- [AtBo 1982] M. F. Atiyah and R. Bott, The Yang-Mills equation over Riemann surfaces, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 308 (1982), 523-615.

- [AtBo 1984] M. F. Atiyah and R. Bott, The moment map and equivariant cohomology, Topology 23 (1984), no. 1, 1-28.

- [BBFMP 1960] A. Borel, G. Bredon, E. E. Floyd, P. Montgomery, and R. Palais, Seminar on transformation groups, Annals of Math. Studies 46. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press 1960.

- [BoTu 2001] R. Bott and L. W. Tu, Equivariant characteristic classes in the Cartan model, in: Geometry, analysis and applications. Proceedings of the International Conference held in memory of V. K. Patodi at Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, August 21-24, 2000. Edited by R. S. Pathak. World Scientific Publishing Co., Inc., River Edge, NJ, 2001, 3-20.

- [Bre 1974] G. E. Bredon, The free part of a torus action and related numerical equalities, Duke Math. J. 41 (1974), 843-854.

- [Bri 2000] M. Brion, Poincaré duality and equivariant (co)homology, Michigan Math. J. 48 (2000), 77-92.

- [BrHe 1993] W. Bruns and J. Herzog, Cohen-Macaulay rings, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, 39. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1993.

- [ChSk 1974] T. Chang and T. Skjelbred, The topological Schur lemma and related results, Ann. of Math. (2) 100 (1974), 307-321.

- [DaJa 1991] M. W. Davis and T. Januszkiewicz, Convex polytopes, Coxeter orbifolds and torus actions, Duke Math. J. 62 (1991), no. 2, 417-451.

- [Duf 1983] J. Duflot, Smooth toral actions, Topology 22 (1983), 253-265.

- [Eis 1995] D. Eisenbud, Commutative algebra with a view toward algebraic geometry, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 150. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1995.

- [Eis 2004] D. Eisenbud, The geometry of syzygies, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 229. Springer-Verlag, New York, 2004.

- [FrPu 2003] M. Franz and V. Puppe, Exact sequences for equivariantly formal spaces, preprint. arXiv:math/0307112.

- [FrPu 2007] M. Franz and V. Puppe, Exact cohomology sequences with integral coefficients for torus actions, Transform. Groups 12 (2007), no. 1, 65-76.

- [FrPu 2008] M. Franz and V. Puppe, Freeness of equivariant cohomology and mutants of compactified representations, Toric topology, 87-98, Contemp. Math. 460, AMS, Providence, RI, 2008.

- [GKM 1998] M. Goresky, R. Kottwitz, and R. MacPherson, Equivariant cohomology, Koszul duality, and the localization theorem, Invent. Math. 131 (1998), no. 1, 25-83.

- [GGK 2002] V. W. Guillemin, V. L. Ginzburg, and Y. Karshon, Moment maps, cobordisms, and Hamiltonian group actions, Mathematical Surveys and Monographs, 96. AMS, Providence, RI, 2002.

- [GuSt 1999] V. W. Guillemin and S. Sternberg, Supersymmetry and equivariant de Rham theory, Springer-Verlag, Berlin 1999.

- [GuZa 2001] V. W. Guillemin and C. Zara, -skeleta, Betti numbers, and equivariant cohomology, Duke Math. J. 107 (2001), no. 2, 283-349.

- [HHH 2005] M. Harada, A. Henriques and T. S. Holm, Computation of generalized equivariant cohomologies of Kac-Moody flag varieties, Adv. Math. 197 (2005), 198-221. Unpublished version: -equivariant cohomology of cell complexes and the case of infinite Grassmannians, arXiv:math/0402079.

- [Hsi 1975] W. Y. Hsiang, Cohomology theory of topological transformation groups, Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete, Band 85. Springer-Verlag, New York-Heidelberg, 1975.

- [MMP 2007] H. Maeda, M. Masuda and T. Panov, Torus graphs and simplicial posets. Adv. Math. 212 (2007), no. 2, 458-483.

- [MaPa 2006] M. Masuda and T. Panov, On the cohomology of torus manifolds, Osaka J. Math. 43 (2006), 711-746.

- [Mic 2008] P. W. Michor, Topics in differential geometry, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, 93. American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI, 2008.

- [Sat 1956] I. Satake, On a generalization of the notion of manifold, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 42 (1956), 359-363.

- [Ser 2000] J.-P. Serre, Local algebra, Translated from the French by CheeWhye Chin. Springer Monographs in Mathematics, Springer-Verlag, Berlin 2000.

- [Sta 1991] R. P. Stanley, -vectors and -vectors of simplicial posets, J. Pure Appl. Algebra 71 (1991), 319-331.